Abstract

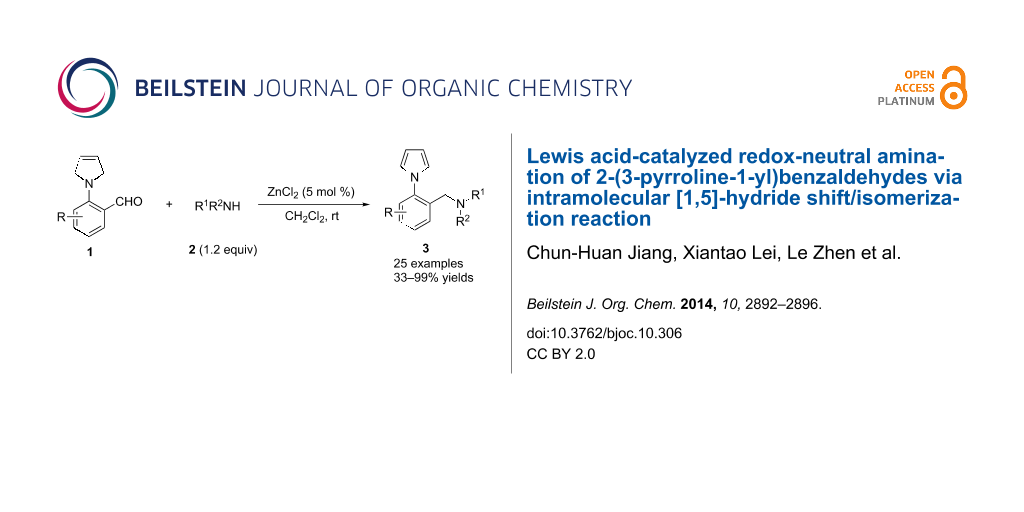

Lewis acid-catalyzed redox-neutral amination of 2-(3-pyrroline-1-yl)benzaldehydes via intramolcular [1,5]-hydride shift/isomerization reaction has been realized, using the inherent reducing power of 3-pyrrolines. A series of N-arylpyrrole containing amines are obtained in high yields.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The direct and selective functionalization of the inactive C(sp3)–H bond constitute an economically attractive strategy for organic syntheses [1-10]. Until now, a number of transition metals can be used for the activation of C–H bonds [11-18]. Among the reported transformations, intramolecular redox processes based on direct functionalization of C(sp3)–H bonds linking with α heteroatoms are useful for the synthesis of structurally diverse amines and ether derivatives [19-30]. On the other hand, compounds containing the N-arylpyrrole moiety serve as important building blocks for the synthesis of various complex molecules and exhibit a larger number of biological effects [31-33].

In 2009, Tunge's group disclosed that N-alkylpyrroles could be formed via a redox isomerization reaction (Scheme 1, reaction 1) [34-36]. Moreover, we recently realized a Lewis acid-catalyzed intramolecular redox reaction using an aldehyde group as the H-shift acceptor to afford (2-(1H-pyrrol-1-yl)phenyl)methanol (Scheme 1, reaction 2) [37]. As part of our interest in expanding the inherent reducing power of 3-pyrrolines, we report herein the Lewis acid-catalyzed redox-neutral amination of 2-(3-pyrroline-1-yl)benzaldehydes using the iminium group as the H-shift acceptor (Scheme 1, reaction 3). Notably, this reaction should meet the requirement that the iminium formation reaction should be faster than the aldehyde redox reaction.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles via redox-neutral reaction.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles via redox-neutral reaction.

Results and Discussion

In our initial investigation, aldehyde 1a and dibenzylamine (2a) were chosen as the model reaction substrates. In the presence of 10 mol % PhCOOH, the reaction of 1a with 2a in DCE at rt for 24 h gave the trisubstituted amine 3a in 50% yield (entry 1, Table 1). Encouraged by this result, we screened readily available Brønsted and Lewis acids (Table 1). Except the Lewis acid AlCl3, other strong Brønsted acids and common Lewis acids could be used as the catalyst in this reaction, affording the desired products in excellent yields (entries 2–8, Table 1). Considering that ZnCl2 is cheaper and easy to handle, it was chosen as the catalyst for further optimization reactions. Furthermore, various solvents such as DCE, CH2Cl2, CHCl3, toluene, CH3CN and THF were examined. All the solvents afforded the desired product in satisfactory yields (entries 8–13, Table 1). Subsequently, the loading of dibenzylamine (2a) and the catalyst was examined. The results show that decreasing the amount of 2a to 1.2 equiv and ZnCl2 to 5 mol % did not affect the yield (entry 16, Table 1).

Table 1: Optimization of the redox-neutral amination reaction.a

|

|

|||||

| entry | catalyst | X | Y | solvent | yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PhCOOH | 1.5 | 10 | DCE | 50 |

| 2 | CF3COOH | 1.5 | 10 | DCE | 87 |

| 3 | p-TsOH.H2O | 1.5 | 10 | DCE | 90 |

| 4 | Sc(OTf)3 | 1.5 | 10 | DCE | 94 |

| 5 | Cu(OTf)2 | 1.5 | 10 | DCE | 94 |

| 6 | Zn(OTf)2 | 1.5 | 10 | DCE | 97 |

| 7 | AlCl3 | 1.5 | 10 | DCE | 76 |

| 8 | ZnCl2 | 1.5 | 10 | DCE | 95 |

| 9 | ZnCl2 | 1.5 | 10 | CH2Cl2 | 97 |

| 10 | ZnCl2 | 1.5 | 10 | CHCl3 | 95 |

| 11 | ZnCl2 | 1.5 | 10 | toluene | 94 |

| 12 | ZnCl2 | 1.5 | 10 | CH3CN | 96 |

| 13 | ZnCl2 | 1.5 | 10 | THF | 71 |

| 14 | ZnCl2 | 1.2 | 10 | CH2Cl2 | 97 |

| 15 | ZnCl2 | 1.0 | 10 | CH2Cl2 | 93 |

| 16 | ZnCl2 | 1.2 | 5 | CH2Cl2 | 95 |

| 17 | ZnCl2 | 1.2 | 2 | CH2Cl2 | 91 |

a1a (0.5 mmol), 2a (X equiv), catalyst (Y mol %), solvent (5 mL), room temperature, 24 h. bIsolated yield.

Finally, we established the optimized reaction conditions using ZnCl2 (5 mol %) as the catalyst and CH2Cl2 as the solvent, and running the reaction at room temperature or under reflux.

Under the optimized conditions, the results of the amination reaction of 2a with various 2-(3-pyrroline-1-yl)benzaldehydes 1 are shown in Scheme 2. The reactions proceeded smoothly to give the corresponding N-arylpyrrole amines 3 in good to excellent yields (71–97% yields). Notably, the substitution of the benzene ring had little effect on the reaction since both electron-donating (3b, 3c) and electron-withdrawing groups (3d–i) were tolerated in the reaction.

Scheme 2: Substrate scope of aryl aldehydes 1. Reagents and conditions: 1 (0.3 mmol), 2a (1.2 equiv), ZnCl2 (5 mol %), CH2Cl2 (3.0 mL). aRoom temperature. bDCE, reflux.

Scheme 2: Substrate scope of aryl aldehydes 1. Reagents and conditions: 1 (0.3 mmol), 2a (1.2 equiv), ZnCl2 (...

Next, the scope of amines 2 was explored. The results are summarized in Scheme 3. Reaction of secondary amines possessing aryl–aryl, alkyl–alkyl and aryl–alkyl moieties yield the corresponding N-arylpyrrole amines 3j–p in high yields (81–94% yields). Various cyclic secondary amines were also good substrates for this reaction, affording the desired products (3q, 3r, 3s) in good to high yields (77–98% yields) with DCE as the solvent under reflux conditions. The reaction with indoline, tetrahydroquinoline, and tetrahydroisoquinoline could also be realized to give products 3t, 3u, and 3v in good yields (76–88% yields), respectively. Finally, primary amines were examined. The reaction with excess benzylamine (5.0 equiv) in the presence of Zn(OTf)2 as the catalyst afforded the desired product 3w in 98% yield. However, when n-BuNH2 was used as the substrate, the yield was reduced to 33% even under high temperature. Notably, according to the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude product, the reaction with phenylamine using Zn(OTf)2 as the catalyst afforded only the corresponding imine product, indicating that the [1,5]-hydride shift/isomerization reaction did not occur. To our delight, this reaction proceeded smoothly at room temperature to give the desired N-arylpyrrole amine 3y in high yield (99% yield) when p-TsOH·H2O was used as the catalyst instead of Zn(OTf)2.

Scheme 3: Substrate scope of amines 2. Reagents and conditions: 1a (0.5 mmol), 2 (1.2 equiv), ZnCl2 (5 mol %), CH2Cl2 (5.0 mL), rt. aReflux. bDCE, reflux. cZn(OTf)2 (5 mol %), n-butylamine (5.0 equiv), DCE, reflux. dp-TsOH·H2O (5 mol %), PhNH2 (5.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, rt.

Scheme 3: Substrate scope of amines 2. Reagents and conditions: 1a (0.5 mmol), 2 (1.2 equiv), ZnCl2 (5 mol %)...

Conclusion

In conclusion, Lewis acid-catalyzed redox-neutral amination of 2-(3-pyrroline-1-yl)benzaldehydes via intramolcular [1,5]-hydride shift/isomerization reaction has been realized. Various types of amines and 2-(3-pyrroline-1-yl)benzaldehydes are well tolerated in this reaction, affording the corresponding N-arylpyrrolamines in good to high yields. Further studies on synthetic applications of [1,5]-hydride shift/isomerization reactions that utilize the inherent reducing power of 3-pyrrolines are underway in our laboratory.

Experimental

General procedure for the preparation of N-arylpyrroles 3: A mixture of benzaldehyde 1 (0.3–0.5 mmol), amine 2 (1.2 equiv) and ZnCl2 (5 mol %) were stirred in dichloromethane or DCE (5.0 mL) at room temperature or reflux and monitored by TLC. After completion of the reaction (about 24 h), the solvent was removed by evaporation and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to give N-arylpyrrole 3.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental details, analytical data, and copies of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the final products. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 3.2 MB | Download |

References

-

Godula, K.; Sames, D. Science 2006, 312, 67–72. doi:10.1126/science.1114731

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bergman, R. G. Nature 2007, 446, 391–393. doi:10.1038/446391a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alberico, D.; Scott, M. E.; Lautens, M. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 174–238. doi:10.1021/cr0509760

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Davies, H. M. L.; Manning, J. R. Nature 2008, 451, 417–424. doi:10.1038/nature06485

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, X.; Engle, K. M.; Wang, D.-H.; Yu, J.-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5094–5115. doi:10.1002/anie.200806273

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jazzar, R.; Hitce, J.; Renaudat, A.; Sofack-Kreutzer, J.; Baudoin, O. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 2654–2672. doi:10.1002/chem.200902374

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lyons, T. W.; Sanford, M. S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1147–1169. doi:10.1021/cr900184e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, J.-Q.; Shi, Z. Top. Curr. Chem. 2010, 292, 1–345. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12356-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Davies, H. M. L.; Du Bois, J.; Yu, J.-Q. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1855–1856. doi:10.1039/c1cs90010b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brückl, T.; Baxter, R. D.; Ishihara, Y.; Baran, P. S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 826–839. doi:10.1021/ar200194b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ackermann, L.; Vicente, R.; Kapdi, A. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9792–9826. doi:10.1002/anie.200902996

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seregin, I. V.; Gevorgyan, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1173–1193. doi:10.1039/B606984N

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Daugulis, O.; Do, H.-Q.; Shabashov, D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1074–1086. doi:10.1021/ar9000058

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cho, S. H.; Kim, J. Y.; Kwak, J.; Chang, S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5068–5083. doi:10.1039/c1cs15082k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuhl, N.; Hopkinson, M. N.; Wencel-Delord, J.; Glorius, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10236–10254. doi:10.1002/anie.201203269

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Collet, F.; Dodd, R. H.; Dauban, P. Chem. Commun. 2009, 5061–5074. doi:10.1039/b905820f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arockiam, P. B.; Bruneau, C.; Dixneuf, P. H. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5879–5918. doi:10.1021/cr300153j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jordan-Hore, J. A.; Johansson, C. C. C.; Gulias, M.; Beck, E. M.; Gaunt, M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16184–16186. doi:10.1021/ja806543s

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tobisu, M.; Chatani, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1683–1684. doi:10.1002/anie.200503866

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pan, S. C. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 1374–1384. doi:10.3762/bjoc.8.159

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, B.; Maulide, N. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 13274–13287. doi:10.1002/chem.201301522

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Haibach, M. C.; Seidel, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5010–5036. doi:10.1002/anie.201306489

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Verboom, W.; van Dijk, B. G.; Reinhoudt, D. N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 3923–3926. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94316-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, C.; Murarka, S.; Seidel, D. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 419–422. doi:10.1021/jo802325x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mori, K.; Ohshima, Y.; Ehara, K.; Akiyama, T. Chem. Lett. 2009, 38, 524–525. doi:10.1246/cl.2009.524

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vadola, P. A.; Carrera, I.; Sames, D. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 6689–6702. doi:10.1021/jo300635m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mori, K.; Kawasaki, T.; Akiyama, T. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1436–1439. doi:10.1021/ol300180w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, Y.-P.; Wu, H.; Chen, D.-F.; Yu, J.; Gong, L.-Z. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 5232–5237. doi:10.1002/chem.201300052

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pastine, S. J.; Sames, D. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5429–5431. doi:10.1021/ol0522283

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jurberg, I. D.; Peng, B.; Wöstefeld, E.; Wasserloos, M.; Maulide, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1950–1953. doi:10.1002/anie.201108639

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yan, R.-L.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.-X.; Ma, C.-W.; Huang, G.-S.; Liang, Y.-M. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 5395–5397. doi:10.1021/jo101022k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Galliford, C. V.; Scheidt, K. A. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 1811–1813. doi:10.1021/jo0624086

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jalal, S.; Sarkar, S.; Bera, K.; Maiti, S.; Jana, U. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 4823–4828. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300172

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pahadi, N. K.; Paley, M.; Jana, R.; Waetzig, S. R.; Tunge, J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16626–16627. doi:10.1021/ja907357g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deb, I.; Das, D.; Seidel, D. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 812–815. doi:10.1021/ol1031359

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ramakumar, K.; Tunge, J. A. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 13056–13058. doi:10.1039/C4CC06369D

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Du, H.-J.; Zhen, L.; Wen, X.; Xu, Q.-L.; Sun, H. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 9716–9719. doi:10.1039/C4OB02009J

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Godula, K.; Sames, D. Science 2006, 312, 67–72. doi:10.1126/science.1114731 |

| 2. | Bergman, R. G. Nature 2007, 446, 391–393. doi:10.1038/446391a |

| 3. | Alberico, D.; Scott, M. E.; Lautens, M. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 174–238. doi:10.1021/cr0509760 |

| 4. | Davies, H. M. L.; Manning, J. R. Nature 2008, 451, 417–424. doi:10.1038/nature06485 |

| 5. | Chen, X.; Engle, K. M.; Wang, D.-H.; Yu, J.-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5094–5115. doi:10.1002/anie.200806273 |

| 6. | Jazzar, R.; Hitce, J.; Renaudat, A.; Sofack-Kreutzer, J.; Baudoin, O. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 2654–2672. doi:10.1002/chem.200902374 |

| 7. | Lyons, T. W.; Sanford, M. S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1147–1169. doi:10.1021/cr900184e |

| 8. | Yu, J.-Q.; Shi, Z. Top. Curr. Chem. 2010, 292, 1–345. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12356-6 |

| 9. | Davies, H. M. L.; Du Bois, J.; Yu, J.-Q. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1855–1856. doi:10.1039/c1cs90010b |

| 10. | Brückl, T.; Baxter, R. D.; Ishihara, Y.; Baran, P. S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 826–839. doi:10.1021/ar200194b |

| 34. | Pahadi, N. K.; Paley, M.; Jana, R.; Waetzig, S. R.; Tunge, J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16626–16627. doi:10.1021/ja907357g |

| 35. | Deb, I.; Das, D.; Seidel, D. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 812–815. doi:10.1021/ol1031359 |

| 36. | Ramakumar, K.; Tunge, J. A. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 13056–13058. doi:10.1039/C4CC06369D |

| 31. | Yan, R.-L.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.-X.; Ma, C.-W.; Huang, G.-S.; Liang, Y.-M. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 5395–5397. doi:10.1021/jo101022k |

| 32. | Galliford, C. V.; Scheidt, K. A. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 1811–1813. doi:10.1021/jo0624086 |

| 33. | Jalal, S.; Sarkar, S.; Bera, K.; Maiti, S.; Jana, U. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 4823–4828. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300172 |

| 19. | Tobisu, M.; Chatani, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1683–1684. doi:10.1002/anie.200503866 |

| 20. | Pan, S. C. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 1374–1384. doi:10.3762/bjoc.8.159 |

| 21. | Peng, B.; Maulide, N. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 13274–13287. doi:10.1002/chem.201301522 |

| 22. | Haibach, M. C.; Seidel, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5010–5036. doi:10.1002/anie.201306489 |

| 23. | Verboom, W.; van Dijk, B. G.; Reinhoudt, D. N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 3923–3926. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94316-8 |

| 24. | Zhang, C.; Murarka, S.; Seidel, D. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 419–422. doi:10.1021/jo802325x |

| 25. | Mori, K.; Ohshima, Y.; Ehara, K.; Akiyama, T. Chem. Lett. 2009, 38, 524–525. doi:10.1246/cl.2009.524 |

| 26. | Vadola, P. A.; Carrera, I.; Sames, D. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 6689–6702. doi:10.1021/jo300635m |

| 27. | Mori, K.; Kawasaki, T.; Akiyama, T. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1436–1439. doi:10.1021/ol300180w |

| 28. | He, Y.-P.; Wu, H.; Chen, D.-F.; Yu, J.; Gong, L.-Z. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 5232–5237. doi:10.1002/chem.201300052 |

| 29. | Pastine, S. J.; Sames, D. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5429–5431. doi:10.1021/ol0522283 |

| 30. | Jurberg, I. D.; Peng, B.; Wöstefeld, E.; Wasserloos, M.; Maulide, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1950–1953. doi:10.1002/anie.201108639 |

| 11. | Ackermann, L.; Vicente, R.; Kapdi, A. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9792–9826. doi:10.1002/anie.200902996 |

| 12. | Seregin, I. V.; Gevorgyan, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1173–1193. doi:10.1039/B606984N |

| 13. | Daugulis, O.; Do, H.-Q.; Shabashov, D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1074–1086. doi:10.1021/ar9000058 |

| 14. | Cho, S. H.; Kim, J. Y.; Kwak, J.; Chang, S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5068–5083. doi:10.1039/c1cs15082k |

| 15. | Kuhl, N.; Hopkinson, M. N.; Wencel-Delord, J.; Glorius, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10236–10254. doi:10.1002/anie.201203269 |

| 16. | Collet, F.; Dodd, R. H.; Dauban, P. Chem. Commun. 2009, 5061–5074. doi:10.1039/b905820f |

| 17. | Arockiam, P. B.; Bruneau, C.; Dixneuf, P. H. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5879–5918. doi:10.1021/cr300153j |

| 18. | Jordan-Hore, J. A.; Johansson, C. C. C.; Gulias, M.; Beck, E. M.; Gaunt, M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16184–16186. doi:10.1021/ja806543s |

| 37. | Du, H.-J.; Zhen, L.; Wen, X.; Xu, Q.-L.; Sun, H. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 9716–9719. doi:10.1039/C4OB02009J |

© 2014 Jiang et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)