Abstract

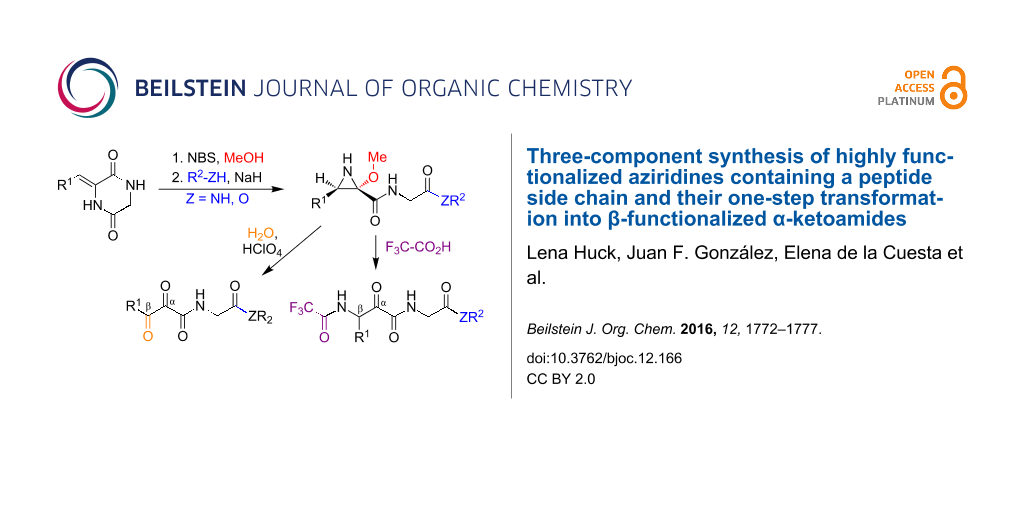

A sequential three-component process is described, starting from 3-arylmethylene-2,5-piperazinediones and involving a one-pot sequence of reactions achieving regioselective opening of the 2,5-diketopiperazine ring and diastereoselective generation of an aziridine ring. This method allows the preparation of N-unprotected, trisubstituted aziridines bearing a peptide side chain under mild conditions. Their transformation into β-trifluoroacetamido-α-ketoamide and α,β-diketoamide frameworks was also achieved in a single step.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Aziridine moieties occur in many natural products and are also encountered in unnatural biologically active compounds including drugs in clinical use, especially in the field of cancer treatment [1]. In the areas of medicinal chemistry and chemical biology, aziridines are of current interest as starting materials for the preparation of peptides [2,3] and the synthesis of peptide-like compounds comprising the aziridine motif [4,5]. Furthermore, the incorporation of an electrophilic aziridine moiety in peptide or peptidomimetic frameworks is an interesting strategy for the design of active site-directed drugs, especially in the field of chemotherapy [6,7].

Aziridines also have an important role in the preparation of further types of nitrogen-containing compounds [8-10]. As a consequence, the preparation of aziridines is of great importance [11-13]. The primary synthetic approaches involve either the direct aziridination of an olefin [14] or the reaction of an imine with diazoalkanes. Alternatively, the reaction of imines with various nucleophiles, including aza-Darzens mechanisms, can lead to aziridine products [15]. However, few known methods allow the synthesis of C-trisubstituted aziridines, particularly for the case of N-unprotected systems [10,16,17].

2,5-Diketopiperazines (DKPs) are readily accessible from amino acids and are versatile synthetic scaffolds [18,19]. Consequently, there is considerable interest in the development of synthetic methodology based on the cleavage of suitably functionalized DKP derivatives [20-22]. In this context, we describe here an efficient regio- and diastereoselective one-pot three-component assembly of trisubstituted aziridines possessing a free NH group and containing a peptidic or peptide-like side chain. Furthermore, we describe the conversion of these compounds into functionalized β-amino-α-ketoamides. This is an important structural fragment that is used in the design of reversible covalent enzyme inhibitors, including the anti-hepatitis C drugs boceprevir and telaprevir, because the electrophilic keto group is able to react reversibly with mercapto or hydroxy groups at the active sites of a variety of enzymes. Existing synthetic approaches to this moiety are normally quite complex and do not easily allow the presence of amino acid side chains on the amide nitrogen [23]. Finally, in order to further underscore the synthetic usefulness of these aziridine scaffolds, we examined their one-pot transformation into α,β-diketoamides and the transformation of the latter compounds into nitrogen heterocycles bearing a peptide side chain (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Summary of the work described in this paper.

Scheme 1: Summary of the work described in this paper.

Results and Discussion

The starting 3-arylmethylene-2,5-piperazinediones 1 were readily available by aldol condensation of 1,4-diacetyl-2,5-piperazinedione with aldehydes in the presence of potassium tert-butoxide, followed by deacetylation with hydrazine hydrate (see the Supporting Information File 1 for further details). As shown in Scheme 2, treatment of these materials with N-bromosuccinimide and methanol in dioxane followed by the addition of 1.2 equivalents of a primary or secondary amine or alcohol in the presence of 2 equivalents of sodium hydride afforded the highly substituted and functionalized aziridine derivatives 2. Under these conditions, it can be assumed that methoxide is the predominant base. The optimal reagent concentration was determined to be 0.2 M, since higher concentrations led to the precipitation of reaction intermediates and lower yields.

The scope of the reaction was investigated and the results are summarized in Table 1. Good yields were obtained independently from the electronic nature of the aryl ring. Bulky R1 aryl groups were well tolerated, as shown by the presence of ortho- substituents in many of the examples (Table 1, entries 3–11). Both primary (Table 1, entries 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 11) and secondary amines (Table 1, entries 2 and 7) could be employed as nucleophiles, and the use of oxygen nucleophiles (methanol) was also possible (Table 1, entries 8 and 10). Nevertheless, steric limitations existed in the latter case, since the reaction did not tolerate the use of bulkier alcohols such as ethanol or propanol, which led only to recovered starting materials. In all cases, the reaction proceeded with full diastereoselectivity, affording the product with a cis relationship between the aryl substituent and the peptide side chain as shown by NOE studies, which are summarized in Figure 1 for compound 2f. One example of a reaction leading to an alkyl substituent at the aziridine C-3 position (R1 = Et) was attempted, but the yield was poor (15%) and the resulting aziridine derivative could not be completely purified.

Table 1: Results obtained in the aziridine synthesis.

| Entry | Compound | R1 | ZR2 | Yield, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2a | C6H5 | n-BuNH | 79 |

| 2 | 2b | C6H5 |

|

58 |

| 3 | 2c | (2,5-MeO)2C6H3 | n-BuNH | 75 |

| 4 | 2d | (2,5-MeO)2C6H3 | n-HexNH | 69 |

| 5 | 2e | 2-ClC6H4 | n-BuNH | 92 |

| 6 | 2f | 2-ClC6H4 | n-HexNH | 73 |

| 7 | 2g | 2-ClC6H4 |

|

61 |

| 8 | 2h | 2-ClC6H4 | OMe | 76 |

| 9 | 2i | 2-NO2C6H4 | n-BuNH | 71 |

| 10 | 2j | 2-NO2C6H4 | OMe | 57 |

| 11 | 2k |

|

n-BuNH | 50 |

Mechanistically, the reaction is proposed to proceed by the pathway summarized in Scheme 3. An initial bromomethoxylation of the starting materials 1 is expected to afford intermediates 3. Although 3 may be formed as a mixture of diastereomers because of the epimerization of the initial adduct, as described in a literature precedent on a similar reaction [24], this is of no consequence for the outcome of the reaction. The next step would involve the base-promoted formation of the bicyclic aziridine 4, where nitrogen conjugation to the adjacent carbonyl would be geometrically constrained. The associated increase in reactivity for this carbonyl would explain the complete selectivity of the diketopiperazine ring opening, with concomitant loss of a molecule of methanol, to furnish azirine 5. Finally, addition of the methanol released in the previous step to the highly strained intermediate 5 would take place anti to the R1 substituent, explaining the observed diastereoselection. This proposal was supported by the isolation of one of its intermediates from the reaction between 3-(2,5-dimethoxybenzylidene)-2,5-piperazinedione and NBS in dioxane containing methanol at room temperature. This reaction led to the corresponding compound 3 in 75% yield, with full regioselectivity but as a 1.7:1 mixture of diastereomers. When this mixture was treated with butylamine and sodium hydride under our standard conditions, compound 2c was isolated in 85% yield.

Scheme 3: Mechanistic proposal accounting for the chemo- and diastereoselective formation of aziridines 2.

Scheme 3: Mechanistic proposal accounting for the chemo- and diastereoselective formation of aziridines 2.

With compounds 2 in hand, we next examined their transformation into β-amino-α-ketoamide derivatives. While the synthetic applications of aziridines have received much attention [11,25-29] there is little precedent of their opening with weak nucleophiles such as carboxylate anions [30]. However, we expected that the presence of the 2-methoxy substituent would facilitate the desired transformation. The initial study was carried out on compound 2e, but we found that a variety of acidic conditions either failed to give any reaction at room temperature or afforded complex mixtures when heated. After some experimentation, we finally discovered that treatment of compound 2e with trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane at 45 °C gave an excellent yield of the β-trifluoroacetamido-α-ketoamide 6d. The method was then applied to a range of representative aziridines 2, allowing the synthesis of the corresponding compounds 6 in excellent yields (Scheme 4 and Table 2).

Scheme 4: Transformation of aziridines 2 into β-trifluoroacetamido-α-ketoamides 6.

Scheme 4: Transformation of aziridines 2 into β-trifluoroacetamido-α-ketoamides 6.

The formation of 6 can be explained by the mechanism summarized in Scheme 5. The acid-promoted opening of the hemiaminal ether function existent in aziridine derivatives 2 because of the presence of the 2-methoxy substituent would furnish oxonium species 7 via a Neber reaction. Its O-demethylation by the trifluoroacetate anion would yield compound 8, whose amino group would finally be trifluoroacetylated by the methyl trifluoroacetate liberated in the previous step, to give 6. Alternatively, loss of a molecule of methanol from starting compound 2 would lead to intermediate 5 (see Scheme 3), whose reaction with trifluoroacetic acid would furnish 9. Neber-type chemistry would afford the oxonium species 10, which would finally be transformed into the observed product 6 by intramolecular transfer of the trifluoroacetyl group.

Scheme 5: Two mechanistic proposals explaining the formation of compounds 6.

Scheme 5: Two mechanistic proposals explaining the formation of compounds 6.

Finally, bearing in mind the interest of 1,2,3-tricarbonyl compounds (vicinal tricarbonyl compounds, VCTs) both as structural fragments of protease inhibitors [31] and synthetic intermediates [32,33], we also explored briefly their direct preparation from compounds 2, together with their application to the synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles bearing a peptide side chain. We discovered that treatment of representative aziridines 2 with perchloric acid in a THF–water reaction medium led to the isolation of the corresponding compounds 11, which were then transformed into pyrazines 12 and quinoxalines 13 via straightforward cyclocondensation reactions with ethylenediamine and o-phenylenediamine, respectively (Scheme 6 and Table 3).

Scheme 6: Transformation of aziridines 2 into vicinal tricarbonyl compounds 11 and transformation of the latter into nitrogen heterocycles 12 and 13, containing a peptide side chain.

Scheme 6: Transformation of aziridines 2 into vicinal tricarbonyl compounds 11 and transformation of the latt...

Table 3: Results of the synthesis of vicinal tricarbonyl compounds 11 and the nitrogen heterocycles 12 and 13 arising from them.

| Entry | Compound | R1 | ZR2 | Yield, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11a | 2-ClC6H4 | n-BuNH | 67 |

| 2 | 11b | (2,5-MeO)2C6H3 | n-BuNH | 64a |

| 3 | 12a | 2-ClC6H4 | n-BuNH | 64 |

| 4 | 12b | (2,5-MeO)2C6H3 | n-BuNH | 67 |

| 5 | 13a | 2-ClC6H4 | n-BuNH | 61 |

| 6 | 13b | (2,5-MeO)2C6H3 | n-BuNH | 74 |

| 7 | 13c | 2-ClC6H4 | OMe | 74 |

aTwo equivalents of perchloric acid were required in this case. The normal reaction conditions (1 equiv HClO4) led to 13% yield of 11b and 52% of compound 14b (see below the mechanistic discussion associated to Scheme 7).

The transformation of 2 into 11 can be explained by the mechanism summarized in Scheme 7, starting with the formation of the previously mentioned intermediate 8, followed by hydrolysis of its imino tautomer to give 14 and a final oxidation by perchloric acid. One of the proposed intermediates (compound 14b) was isolated by lowering the amount of perchloric acid, and was transformed into 11b under the general conditions employed for the preparation of 11 from 2.

Scheme 7: Mechanistic proposal for the transformation of aziridines 2 into compounds 11.

Scheme 7: Mechanistic proposal for the transformation of aziridines 2 into compounds 11.

Conclusion

We have developed an efficient, mechanistically novel entry into polysubstituted, functionalized aziridines. Our method is based on a sequential three-component reaction initiated by bromomethoxylation of the exocyclic double bond in readily available 3-arylmethylene-2,5-piperazinediones, followed by a domino process involving three consecutive nucleophilic attacks that achieve regioselective opening of the diketopiperazine ring and diastereoselective generation of the aziridine ring. The protocol described here proceeds under mild and functional group-tolerant conditions, allowing the synthesis of N-unprotected, trisubstituted aziridines bearing a peptide side chain. The synthetic application of these aziridines was demonstrated by their one-pot transformation into β-trifluoroacetamido-α-ketoamides, thus providing a fast and efficient access to an important pharmacophore in the design of enzyme inhibitors. Furthermore, the aziridines could also be transformed into α,β-diketoamides, which were suitable precursors for nitrogen heterocycles bearing a peptide side chain.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental section, copies of 1H NMR, 13C NMR and ESIMS spectra of all new compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 5.6 MB | Download |

References

-

Avendaño, C.; Menéndez, J. C. DNA Alkylating Agents. Medicinal Chemistry of Anticancer Drugs, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, U.K., 2015; pp 197–242.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Roxin, Á.; Chen, J.; Scully, C. C. G.; Rotstein, B. H.; Yudin, A. K.; Zheng, G. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23, 1387–1395. doi:10.1021/bc300239a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dyer, F. B.; Park, C.-M.; Joseph, R.; Garner, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20033–20035. doi:10.1021/ja207133t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Diaper, C. M.; Sutherland, A.; Pillai, B.; James, M. N. G.; Semchuk, P.; Blanchard, J. S.; Vederas, J. C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 4402–4411. doi:10.1039/b513409a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Galonić, D. P.; Ide, N. D.; van der Donk, W. A.; Gin, D. Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 7359–7369. doi:10.1021/ja050304r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lin, C.; Kwong, A. D.; Perni, R. B. Infect. Disord.: Drug Targets 2006, 6, 3–16. doi:10.2174/187152606776056706

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Njoroge, F. G.; Chen, K. X.; Shih, N.-Y.; Piwinski, J. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 50–59. doi:10.1021/ar700109k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ibuka, T. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998, 27, 145–154. doi:10.1039/a827145z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pellissier, H. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 1509–1555. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.11.089

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yudin, A. K., Ed. Aziridines and epoxides in organic synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. doi:10.1002/3527607862

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sweeney, J. B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 247–258. doi:10.1039/B006015L

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Jenkins, D. M. Synlett 2012, 23, 1267–1270. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1290977

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jung, N.; Bräse, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5538–5540. doi:10.1002/anie.201200966

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hashimoto, T.; Nakatsu, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Maruoka, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9730–9733. doi:10.1021/ja203901h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Künzi, S. A.; Morandi, B.; Carreira, E. M. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1900–1901. doi:10.1021/ol300539e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Davis, F. A.; Deng, J. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1707–1710. doi:10.1021/ol070365p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Baumann, M.; Baxendale, I. Synlett 2016, 27, 159–163. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1560391

Return to citation in text: [1] -

González, J. F.; Ortín, I.; de la Cuesta, E.; Menéndez, J. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6902–6915. doi:10.1039/c2cs35158g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Borthwick, A. D. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3641–3716. doi:10.1021/cr200398y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

González, J. F.; de la Cuesta, E.; Avendaño, C. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 2762–2771. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.01.047

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bull, S. D.; Davies, S. G.; Garner, A. C.; O’Shea, M. O. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 3281–3287. doi:10.1039/B108621A

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Farran, D.; Echalier, D.; Martínez, J.; Dewynter, G. J. Pept. Sci. 2009, 15, 474–478. doi:10.1002/psc.1139

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kher, S.; Jirgensons, A. Curr. Org. Chem. 2014, 18, 2240–2269. doi:10.2174/1385272819666140818223225

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bartels, A.; Jones, P. G.; Liebscher, J. Synthesis 2003, 67–72. doi:10.1055/s-2003-36259

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Florio, S.; Luisi, R. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5128–5157. doi:10.1021/cr100032b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krake, S. H.; Bergmeier, S. C. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 7337–7360. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.06.064

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Botuha, C.; Chemla, F.; Ferreira, F.; Pérez-Luna, A. Aziridines in Natural Product Synthesis. In Heterocycles in Natural Product Synthesis; Majumdar, K. C.; Chattopadhyay, S. K., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2011; pp 3–40.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stanković, S.; D’hooghe, M.; Catak, S.; Eum, H.; Waroquier, M.; Van Speybroeck, V.; De Kimpe, N.; Ha, H.-J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 643–665. doi:10.1039/C1CS15140A

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Degennaro, L.; Trinchera, P.; Luisi, R. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7881–7929. doi:10.1021/cr400553c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumar, M.; Gandhi, S.; Singh Kalra, S.; Singh, V. K. Synth. Commun. 2008, 38, 1527–1532. doi:10.1080/00397910801928723

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wasserman, H. H.; Chen, J.-H.; Xia, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1401–1402. doi:10.1021/ja9840302

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rubin, M. B.; Gleiter, R. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1121–1164. doi:10.1021/cr960079j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wasserman, H. H.; Parr, J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 687–701. doi:10.1021/ar0300221

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 32. | Rubin, M. B.; Gleiter, R. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1121–1164. doi:10.1021/cr960079j |

| 33. | Wasserman, H. H.; Parr, J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 687–701. doi:10.1021/ar0300221 |

| 1. | Avendaño, C.; Menéndez, J. C. DNA Alkylating Agents. Medicinal Chemistry of Anticancer Drugs, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, U.K., 2015; pp 197–242. |

| 8. | Ibuka, T. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998, 27, 145–154. doi:10.1039/a827145z |

| 9. | Pellissier, H. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 1509–1555. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.11.089 |

| 10. | Yudin, A. K., Ed. Aziridines and epoxides in organic synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. doi:10.1002/3527607862 |

| 30. | Kumar, M.; Gandhi, S.; Singh Kalra, S.; Singh, V. K. Synth. Commun. 2008, 38, 1527–1532. doi:10.1080/00397910801928723 |

| 6. | Lin, C.; Kwong, A. D.; Perni, R. B. Infect. Disord.: Drug Targets 2006, 6, 3–16. doi:10.2174/187152606776056706 |

| 7. | Njoroge, F. G.; Chen, K. X.; Shih, N.-Y.; Piwinski, J. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 50–59. doi:10.1021/ar700109k |

| 31. | Wasserman, H. H.; Chen, J.-H.; Xia, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1401–1402. doi:10.1021/ja9840302 |

| 4. | Diaper, C. M.; Sutherland, A.; Pillai, B.; James, M. N. G.; Semchuk, P.; Blanchard, J. S.; Vederas, J. C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 4402–4411. doi:10.1039/b513409a |

| 5. | Galonić, D. P.; Ide, N. D.; van der Donk, W. A.; Gin, D. Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 7359–7369. doi:10.1021/ja050304r |

| 24. | Bartels, A.; Jones, P. G.; Liebscher, J. Synthesis 2003, 67–72. doi:10.1055/s-2003-36259 |

| 2. | Roxin, Á.; Chen, J.; Scully, C. C. G.; Rotstein, B. H.; Yudin, A. K.; Zheng, G. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23, 1387–1395. doi:10.1021/bc300239a |

| 3. | Dyer, F. B.; Park, C.-M.; Joseph, R.; Garner, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20033–20035. doi:10.1021/ja207133t |

| 11. | Sweeney, J. B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 247–258. doi:10.1039/B006015L |

| 25. | Florio, S.; Luisi, R. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5128–5157. doi:10.1021/cr100032b |

| 26. | Krake, S. H.; Bergmeier, S. C. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 7337–7360. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.06.064 |

| 27. | Botuha, C.; Chemla, F.; Ferreira, F.; Pérez-Luna, A. Aziridines in Natural Product Synthesis. In Heterocycles in Natural Product Synthesis; Majumdar, K. C.; Chattopadhyay, S. K., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2011; pp 3–40. |

| 28. | Stanković, S.; D’hooghe, M.; Catak, S.; Eum, H.; Waroquier, M.; Van Speybroeck, V.; De Kimpe, N.; Ha, H.-J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 643–665. doi:10.1039/C1CS15140A |

| 29. | Degennaro, L.; Trinchera, P.; Luisi, R. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7881–7929. doi:10.1021/cr400553c |

| 10. | Yudin, A. K., Ed. Aziridines and epoxides in organic synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. doi:10.1002/3527607862 |

| 16. | Davis, F. A.; Deng, J. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1707–1710. doi:10.1021/ol070365p |

| 17. | Baumann, M.; Baxendale, I. Synlett 2016, 27, 159–163. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1560391 |

| 20. | González, J. F.; de la Cuesta, E.; Avendaño, C. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 2762–2771. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.01.047 |

| 21. | Bull, S. D.; Davies, S. G.; Garner, A. C.; O’Shea, M. O. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 3281–3287. doi:10.1039/B108621A |

| 22. | Farran, D.; Echalier, D.; Martínez, J.; Dewynter, G. J. Pept. Sci. 2009, 15, 474–478. doi:10.1002/psc.1139 |

| 15. | Künzi, S. A.; Morandi, B.; Carreira, E. M. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1900–1901. doi:10.1021/ol300539e |

| 23. | Kher, S.; Jirgensons, A. Curr. Org. Chem. 2014, 18, 2240–2269. doi:10.2174/1385272819666140818223225 |

| 14. | Hashimoto, T.; Nakatsu, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Maruoka, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9730–9733. doi:10.1021/ja203901h |

| 11. | Sweeney, J. B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 247–258. doi:10.1039/B006015L |

| 12. | Jenkins, D. M. Synlett 2012, 23, 1267–1270. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1290977 |

| 13. | Jung, N.; Bräse, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5538–5540. doi:10.1002/anie.201200966 |

| 18. | González, J. F.; Ortín, I.; de la Cuesta, E.; Menéndez, J. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6902–6915. doi:10.1039/c2cs35158g |

| 19. | Borthwick, A. D. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3641–3716. doi:10.1021/cr200398y |

© 2016 Huck et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)