Abstract

The specific rates of solvolysis of isobutyl chloroformate (1) are reported at 40.0 °C and those for isobutyl chlorothioformate (2) are reported at 25.0 °C, in a variety of pure and binary aqueous organic mixtures with wide ranging nucleophilicity and ionizing power. For 1, we also report the first-order rate constants determined at different temperatures in pure ethanol (EtOH), methanol (MeOH), 80% EtOH, and in both 97% and 70% 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE). The enthalpy (ΔH≠) and entropy (ΔS≠) of activation values obtained from Arrhenius plots for 1 in these five solvents are reported. The specific rates of solvolysis were analyzed using the extended Grunwald–Winstein equation. Results obtained from correlation analysis using this linear free energy relationship (LFER) reinforce our previous suggestion that side-by-side addition–elimination and ionization mechanisms operate, and the relative importance is dependent on the type of chloro- or chlorothioformate substrate and the solvent.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Alkyl chloro- and chlorothioformate esters are frequently used precursors [1-4] in the synthesis of pharmaceutical intermediates. Hence, it is important to comprehend the correlations between their chemical structure, chemical reactivity, and solvent effects. This knowledge can then be applied to the development of compounds that are designed to either stimulate or block other chemicals from interacting with targeted receptors. The effects of solvent variation upon the available specific rates of solvolysis of adamantyl [5,6], methyl [7], ethyl [8], 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl [9], n-propyl [10], isopropyl [11,12], n-octyl [13], and neopentyl [14] chloroformate esters, and those of methyl [15], ethyl [8], and isopropyl [16] chlorothioformate esters have been successfully analyzed using the extended [17-19] Grunwald–Winstein equation (Equation 1). In Equation 1, k and k0 are the specific rates of solvolysis in a given solvent and in the standard solvent (80% ethanol), respectively, l estimates the sensitivity to changes in solvent nucleophilicity (NT), m represents the sensitivity to changes in the solvent ionizing power YCl, and c is a constant (residual) term.

Kevill and Anderson developed NT scales based on the solvolyses of the S-methyldibenzothiophenium ion [20,21] for considerations of solvent nucleophilicity, and Bentley et al. have recommended YCl scales [22-25] based on the solvolyses of adamantyl derivatives for estimating the sensitivity to solvent ionizing power.

In reactions where the reaction center is adjacent to a π-system, or in α-haloalkyl aryl compounds that proceed via anchimeric assistance (k∆), Kevill and D’Souza proposed the addition of an aromatic ring parameter (hI) term [26-28] to Equation 1 to give Equation 2. In Equation 2, h represents the sensitivity of solvolyses to changes in the aromatic ring parameter I.

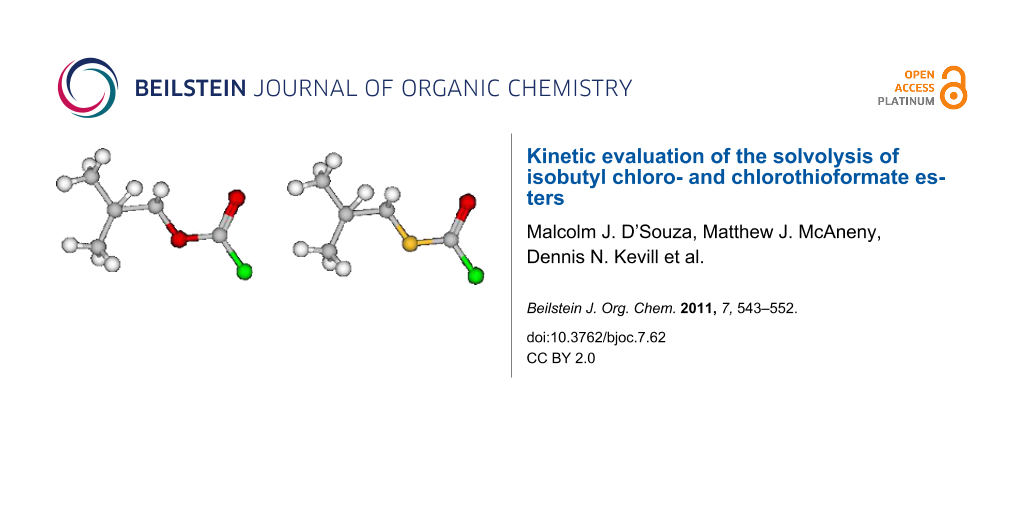

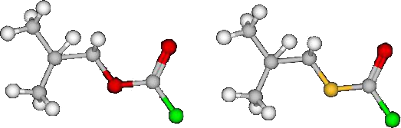

Lee [29], Bentley [30] and others [3,31-38], used computational and experimental evidence to show that the chloroformate and chlorothioformate esters always exist in a syn conformation where the halogen atom is in a trans position with respect to the alkyl group. In Figure 1, the molecular structures for syn-isobutyl chloroformate (1), syn-isobutyl chlorothioformate (2), phenyl chloroformate (3), phenyl chlorodithioformate (4), and isopropyl chloroformate (5), and their corresponding 3-D structures 1', 2', 3', 4' and 5' are shown in the most stable geometries for RXCXCl (where X = S or O) which exist in a conformation where the C=X is syn with respect to R.

Figure 1: Molecular structures of syn-isobutyl chloroformate (1), syn-isobutyl chlorothioformate (2), phenyl chloroformate (3), phenyl chlorodithioformate (4), and isopropyl chloroformate (5). The 3-D images for syn-isobutyl chloroformate (1'), syn-isobutyl chlorothioformate (2'), phenyl chloroformate (3'), phenyl chlorodithioformate (4'), and isopropyl chloroformate (5') are also shown.

Figure 1: Molecular structures of syn-isobutyl chloroformate (1), syn-isobutyl chlorothioformate (2), phenyl ...

In a recent review [17], commemorating the 60th anniversary of the Grunwald–Winstein equation, we previously published reported analyses [5-8,10,11,13,39-49] that were obtained using Equation 1, with examples of several alkyl and aryl chloro-, chlorothio-, chlorothiono-, and dithiochloroformate esters. For these esters, we proposed [17] side-by-side addition–elimination (AN + DN) and ionization (SN1) solvolytic mechanisms, with proportions that were dependent on the type of RXCXCl (X = O or S) substrate, solvent nucleophilicity, and the ionizing ability of the solvents studied.

At one extreme when R = Ph in phenyl chloroformate (PhOCOCl, 3), due to the presence of two electronegative oxygen atoms and the planarity of the phenoxy group (3'), compound 3 [17,39,40] was found to solvolyze in all of the 49 solvents studied solely by an addition–elimination (AN + DN) pathway (Scheme 1) with formation of the tetrahedral intermediate as the rate-determining step. When both oxygens are replaced by the more polarizable sulfur as in phenyl chlorodithioformate (PhSCSCl, 4) [17,40,45], the mechanism of reaction was found to completely switch over to an ionization (SN1) pathway (Scheme 2) in all of the pure and binary aqueous organic mixtures studied. This tendency to follow an ionization process in such sulfur-for-oxygen substitutions occurs primarily as a result of the formation of a more favored resonance-stabilized transition-state (Scheme 2) [40,45].

Scheme 1: Stepwise addition–elimination mechanism through a tetrahedral intermediate for solvolysis of chloroformate esters.

Scheme 1: Stepwise addition–elimination mechanism through a tetrahedral intermediate for solvolysis of chloro...

Scheme 2: Unimolecular solvolytic pathway for the dithioformate esters.

Scheme 2: Unimolecular solvolytic pathway for the dithioformate esters.

We have since recommended [17] that the l (1.66) and m (0.56) values obtained by using Equation 1 for the solvolyses of 3, and values of l (0.69) and m (0.95) obtained for the solvolyses of 4, be taken as appropriate standards for the bimolecular addition–elimination and unimolecular ionization (without fragmentation) pathways, respectively. The appreciable sensitivity to solvent nucleophilicity (0.69) seen in the ionization–solvolysis of 4, points to strong rear-side nucleophilic solvation of the developing resonance-stabilized carbocation. Another useful tool for mechanistic studies is the l/m ratio. We have found [17] that values >2.7 are typical of solvolytic mechanisms proceeding by an addition–elimination pathway with the addition-step being rate-determining (Scheme 1). Ratios between 0.5 and 1.0 signify a unimolecular ionization mechanism with strong rear-side nucleophilic solvation of the developing resonance-stabilized transition-state, while l/m values <<0.5 are indicative of an ionization–fragmentation process.

Early studies by other groups favored competing SN1 and SN2 pathways for the alkyl chloro-, chlorothio-, chlorothiono-, and dithiochloroformates [50-59]. Upon evaluating the rates of hydrolysis in aqueous solvents, Queen [54,55] suggested that with increasing electron donation to the chlorocarbonyl group in alkyl chloro- and chlorothioformates, the positive entropies and low solvent isotope effects pointed to a mechanism involving a unimolecular acyl–halogen bond fission. More recent studies on alkyl and aryl chlorothio-, chlorodithio-, and chlorothionoformate esters favor a stepwise mechanism via a zwitterionic tetrahedral intermediate [60-65].

Isobutyl chloroformate (1) and isobutyl chlorothioformate (2) have found use as specific precursors in novel synthetic routes for the preparation of peptidyl carbamate and thiocarbamate inhibitors of the enzyme elastase [66]. In Figure 1, the 3-D images of isobutyl chloroformate (1') and isobutyl chlorothioformate (2') are presented. In these figures, it is clear that the isopropyl group is pushed out of the plane due the presence of a carbon atom next to the ether or thioether atom in 1' and 2'. This could have an impact on any potential steric or electronic effects, due to presence of the isobutyl group, on the specific rates of reaction.

In this article we present determinations of the specific rates of reaction for isobutyl chloroformate (iBuOCOCl, 1) at 40.0 °C and of isobutyl chlorothioformate (iBuSCOCl, 2) at 25.0 °C in a variety of pure and binary aqueous organic solvents with wide ranging nucleophilicity and ionizing power values. Using Equation 1, we analyze in detail values for l and m obtained for 1 and 2 compared to those of the recommended standards (3 and 4) for such substrates, and also in comparison to the l and m values of other previously reported alkyl chloro- and chlorothioformate esters. We will also seek evidence for any changes in mechanism due to the presence of the isobutyl group. For 1, we report studies at additional temperatures in five organic solvents to determine the corresponding values of the enthalpy (ΔH≠) and entropy (ΔS≠) of activation.

Results and Discussion

The specific rates of solvolysis of 1 at 40.0 °C and of 2 at 25.0 °C, are reported in Table 1. Also presented in Table 1 are the NT and YCl values needed for the multiple correlation analysis of the assembled data using Equation 1.

Table 1: Specific rates of solvolysis (k) of isobutyl chloroformate (1) and isobutyl chlorothioformate (2), in several binary solvents and literature values for NT and YCl.

| Solventa |

1 at 40.0 °C

104 k (s−1)b |

2 at 25.0 °C

105 k (s−1)b |

NTc | YCld |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% MeOH | 3.28 ± 0.04 | 2.27 ± 0.14 | 0.17 | −1.2 |

| 90% MeOH | 6.25 ± 0.03 | 4.63 ± 0.22 | −0.01 | −0.20 |

| 80% MeOH | 8.74 ± 0.08 | 7.57 ± 0.19 | −0.06 | 0.67 |

| 70% MeOH | 11.6 ± 0.2 | −0.40 | 1.46 | |

| 100% EtOH | 0.848 ± 0.053 | 1.01 ± 0.09 | 0.37 | −2.50 |

| 90% EtOH | 1.97 ± 0.05 | 1.22 ± 0.10 | 0.16 | −0.90 |

| 80% EtOH | 2.65 ± 0.02 | 2.99 ± 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 70% EtOH | 3.28 ± 0.02 | −0.20 | 0.78 | |

| 60% EtOH | 4.19 ± 0.05 | −0.38 | 1.38 | |

| 50% EtOH | 5.12 ± 0.05 | −0.58 | 2.02 | |

| 90% Acetone | 0.113 ± 0.027 | −0.35 | −2.39 | |

| 80% Acetone | 0.316 ± 0.002 | 0.201 ± 0.015 | −0.37 | −0.80 |

| 70% Acetone | 0.652 ± 0.004 | 1.06 ± 0.09 | −0.42 | 0.17 |

| 60% Acetone | 1.02 ± 0.02 | −0.52 | 1.00 | |

| 97% TFE (w/w) | 0.0511 ± 0.0007 | 6.01 ± 0.10 | −3.30 | 2.83 |

| 90% TFE (w/w) | 0.0690 ± 0.0004 | 11.7 ± 0.8 | −2.55 | 2.85 |

| 70% TFE (w/w) | 0.263 ± 0.005 | 40.8 ± 2.3 | −1.98 | 2.96 |

| 50% TFE (w/w) | 0.775 ± 0.002 | −1.73 | 3.16 | |

| 80% T-20% E | 0.0289 ± 0.0005 | 1.47 ± 0.09 | −1.76 | 1.89 |

| 60% T-40% E | 0.106 ± 0.001 | 0.688 ± 0.007 | −0.94 | 0.63 |

| 50% T-50% E | 0.299 ± 0.021 | −0.64 | 0.60 | |

| 40% T-60% E | 0.283 ± 0.008 | 0.465 ± 0.016 | −0.34 | −0.48 |

| 20% T-80% E | 0.561 ± 0.006 | 0.521 ± 0.027 | 0.08 | −1.42 |

| 97% HFIP (w/w) | 66.0 ± 2.9 | −5.26 | 5.17 | |

| 90% HFIP (w/w) | 48.2 ± 1.6 | −3.84 | 4.41 | |

| 70% HFIP (w/w) | 78.4 ± 2.0 | −2.94 | 3.83 | |

aSubstrate concentration of ca. 0.0052 M; binary solvents on a volume–volume basis at 25.0 °C, except for TFE-H2O and HFIP-H2O (1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol/water) solvents which are on a weight–weight basis. T-E are TFE-ethanol mixtures. bWith associated standard deviation. cReferences [20,21]. dReferences [22-25].

For 1, we report in Table 2 the first-order rate constants determined at different temperatures in pure ethanol (EtOH), methanol (MeOH), 80% EtOH, 97% 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE) and 70% TFE. The corresponding enthalpy (ΔH≠) and entropy (ΔS≠) of activation values obtained from Arrhenius plots for 1 in these five mixtures are also reported in Table 2.

Table 2: Specific rates for solvolysis of isobutyl chloroformate (1) at various temperatures and the enthalpies and entropies of activation.

| Solventa | Temp. (°C) | 104 k (s−1) | ΔH≠ (kcal mol−1)b | ΔS≠ (cal mol−1K−1)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% MeOH | 40.0 | 3.27 ± 0.05 | 14.1 ± 0.3 | −29.6 ± 0.9 |

| 45.0 | 4.63 ± 0.04 | |||

| 50.0 | 6.85 ± 0.06 | |||

| 55.0 | 9.54 ± 0.07 | |||

| 100% EtOH | 40.0 | 0.848 ± 0.005 | 15.2 ± 0.05 | −28.6 ± 0.2 |

| 45.0 | 1.27 ± 0.01 | |||

| 50.0 | 1.89 ± 0.02 | |||

| 55.0 | 2.71 ± 0.02 | |||

| 80% EtOH | 40.0 | 2.65 ± 0.02 | 14.0 ± 0.1 | −30.4 ± 0.3 |

| 45.0 | 3.85 ± 0.05 | |||

| 50.0 | 5.53 ± 0.05 | |||

| 55.0 | 7.732 ± 0.08 | |||

| 70% TFE | 40.0 | 0.263 ± 0.006 | 20.6 ± 0.4 | −13.8 ± 1.3 |

| 45.0 | 0.468 ± 0.004 | |||

| 50.0 | 0.775 ± 0.004 | |||

| 55.0 | 1.26 ± 0.01 | |||

| 97% TFE | 40.0 | 0.0511 ± 0.0007 | 21.5 ± 0.2 | −14.3 ± 0.6 |

| 55.0 | 0.266 ± 0.003 | |||

| 60.0 | 0.429 ± 0.009 | |||

| 65.0 | 0.704 ± 0.006 | |||

aVolume–volume basis at 25.0 °C. bWith associated standard error.

The l, m, and c values obtained for 1 and 2, together with the multiple correlation coefficients (R) and the F-test values are reported in Table 3, together with corresponding values from the literature for solvolyses of other chloroformate and chlorothioformate esters.

Table 3: Correlation of the specific rates of solvolysis of iBuOCOCl and iBuSCOCl (this study) and several other chloroformate and chlorothioformate esters (values from the literature), using the extended Grunwald–Winstein equation (Equation 1).

| Substrate | na | lb | mb | cb | l/m | Rc | Fd | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhOCOClg | 49 | 1.66 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 2.95 | 0.980 | 568 | A–Ee |

| 2-AdOCOClg | 19 | 0.03 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | −0.10 ± 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.971 | 130 | If |

| 1-AdOCOClg | 11 | 0.08 ± 0.20 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 0.06 ± 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.985 | 133 | If |

| MeOCOClg | 19 | 1.59 ± 0.09 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 2.74 | 0.977 | 171 | A–E |

| EtOCOClg | 28 | 1.56 ± 0.09 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.24 | 2.84 | 0.967 | 179 | A–E |

| 7 | 0.69 ± 0.13 | 0.82 ± 0.16 | −2.40 ± 0.27 | 0.84 | 0.946 | 17 | SN1 | |

| n-PrOCOClg | 22 | 1.57 ± 0.12 | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 2.79 | 0.947 | 83 | A–E |

| 6 | 0.40 ± 0.12 | 0.64 ± 0.13 | −2.45 ± 0.27 | 0.63 | 0.942 | 11 | SN1 | |

| iPrOCOClg | 9 | 1.35 ± 0.22 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 3.38 | 0.960 | 35 | A–E |

| 16 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | −0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.982 | 176 | If | |

| iBuOCOClh | 18 | 1.82 ± 0.15 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 3.43 | 0.957 | 82 | A–E |

| neoPenOCOClg | 13 | 1.76 ± 0.14 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 3.67 | 0.977 | 226 | A–E |

| 8 | 0.36 ± 0.10 | 0.81 ± 0.14 | −2.79 ± 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.938 | 18 | SN1 | |

| PhSCSClg | 31 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.987 | 521 | SN1 |

| MeSCOClg | 12 | 1.48 ± 0.18 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.08 | 3.36 | 0.949 | 40 | A–E |

| 8 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | −0.27 ± 0.18 | 0.93 | 0.987 | 95 | SN1 | |

| EtSCOClg | 19 | 0.66 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.07 | −0.16 ± 0.31 | 0.71 | 0.961 | 96 | SN1 |

| iPrSCOClg | 19 | 0.38 ± 0.11 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | −0.28 ± 0.10 | 0.53 | 0.961 | 97 | SN1 |

| iBuSCOCli | 15 | 0.42 ± 0.13 | 0.73 ± 0.09 | −0.37 ± 0.13 | 0.58 | 0.961 | 73 | SN1 |

| PhSCOClg | 16 | 1.74 ± 0.17 | 0.48 ± 0.07 | 0.19 ± 0.23 | 3.63 | 0.946 | 55 | A–E |

| 6 | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | −2.29 ± 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.983 | 44 | SN1 | |

an is the number of solvents. bWith associated standard error. cMultiple Correlation Coefficient. dF-test value. eAddition–elimination. fIonization–fragmentation. gSee text for references giving the source of this data. hNo 97–50% TFE. iNo 100%, 90% EtOH and MeOH, no 20% T-80% E.

As can be seen in Table 1, the pseudo first-order rate constants for 1 and 2 gradually increase as the amount of water is increased in the binary aqueous–organic solvents. This observation holds true even in the highly ionizing fluoroalcohols and can be attributed to solute–solvent interactions in the transition-state where both nucleophilicity and ionizing power play an important role. The very negative entropies of activation observed for 1 in the aqueous alcohols are typical for substrates that undergo solvolysis by a bimolecular process. The negative entropies of activation (−28.6 to −30.4 cal mol−1 K−1) in EtOH, MeOH and 80% EtOH are similar to those observed for the simplest primary alkyl chloroformate, methyl chloroformate (MeOCOCl) [67], where attack at the acyl carbon in an addition–elimination (AN + DN) process was indicated as the rate-determining step. In order to evaluate the details of the interactions at the transition-state for 1, we statistically analyzed (using Equation 1) the rates of reaction using multiple regression analysis. In all 22 solvents we obtained l = 1.11 ± 0.14, m = 0.43 ± 0.08, R = 0.886, F-test = 35, and c = 0.01 ± 0.10. The poor correlation coefficient and rather low F-test value was a strong indication of the possibility of superimposed dual mechanisms occurring within the range of solvent systems studied.

As mentioned in the introduction, PhOCOCl (3) was shown to solvolyze in all of the 49 solvents studied by the addition–elimination process with a rate-determining addition step [39,40]. Using the similarity model concept [68], a plot of log (k/k0) for iBuOCOCl (1) in the 22 solvents studied against log (k/k0) for PhOCOCl (3) is shown in Figure 2. This plot results in a weak correlation with R = 0.913, F-test = 101, slope = 0.62 ± 0.06, and c = −0.08 ± 0.08. It is further observed in Figure 2 that the four aqueous TFE mixtures clearly lie above the line of best fit. Removal of these four points significantly improves the correlation analyses between 1 and 3 with results of R = 0.988, F-test = 659, slope = 0.947 ± 0.04 and c = −0.02 ± 0.03. This indicates that the mechanism of reaction for 1 and 3 in the remaining 18 pure and binary solvents (no aqueous TFE solvents) are identical.

Figure 2: The plot of log (k/k0) for iBuOCOCl (1) against log (k/k0) for PhOCOCl (3).

Figure 2: The plot of log (k/k0) for iBuOCOCl (1) against log (k/k0) for PhOCOCl (3).

For 1, analysis was performed for 18 solvents (no aqueous TFE) using Equation 1, and we obtained (reported in Table 3) l = 1.82 ± 0.15, m = 0.53 ± 0.05, R = 0.957, F-test = 82, and c = 0.18 ± 0.07. Such improvements seen in the correlation coefficient and F-test values for solvolyses of 1 on removal of the four aqueous TFE mixtures indicate that the data is now robust (Figure 3). The l/m ratio of 3.43 falls within the range (shown in Table 3) observed for the other alkyl chloroformate esters in the more nucleophilic solvents.

Figure 3:

The plot of log (k/k0) for isobutyl chloroformate (1) against 1.82 NT + 0.53 YCl in eighteen pure and binary solvents. The points for the four aqueous TFE values were not included in the correlation.

They are added here to show the extent of their deviation.

Figure 3: The plot of log (k/k0) for isobutyl chloroformate (1) against 1.82 NT + 0.53 YCl in eighteen pure a...

Previous solvolytic studies with primary alkyl chloroformates such as methyl chloroformate (MeOCOCl) [7], ethyl chloroformate (EtOCOCl) [8], and n-propyl chloroformate (n-PrOCOCl) [10] provided evidence that a bimolecular association–dissociation (addition–elimination) process was favored in the more nucleophilic solvents, while an ionization pathway was dominant in the highly ionizing solvents, including the fluoroalcohols with high fluoroalcohol content [7,8,10]. The l/m ratios for these three substrates in the more nucleophilic solvents (listed in Table 3) are almost identical in value (2.74, 2.84, and 2.79, respectively) and are very similar to the value of 2.94 observed for 3.

The only two branched alkyl chloroformates that have been studied in detail using a Grunwald–Winstein analysis are isopropyl chloroformate (iPrOCOCl) [11,12] and neopentyl chloroformate (neoPenOCOCl) [14]. The secondary alkyl chloroformate, iPrOCOCl (5) [11,12], was found to solvolyze in a majority of the solvents studied by a mechanism similar to that proposed for the tertiary 1- or 2-adamantyl chloroformates [5,6]. This pathway included a unimolecular fragmentation–ionization process with loss of carbon dioxide [5,6,11,12]. For 5, in nine of the more nucleophilic solvents the l/m ratio of 3.38 (Table 3) was a typical value for an addition–elimination (association–dissociation) mechanism [12].

We have proposed that neopentyl chloroformate (neoPenOCOCl) [14] solvolyzes in the HFIP rich mixtures with a Wagner–Meerwein 1,2-methyl shift leading to the formation of a tertiary pentyl cation. In 13 of the more nucleophilic solvents the l/m ratio of 3.67 (Table 3) for neoPenOCOCl was found to be typical of a bimolecular AN + DN process [14].

The higher errors associated with the l values, and the higher l/m ratios observed for iBuOCOCl (1), iPrOCOCl (5), and neoPenOCOCl, in the more nucleophilic solvents (3.43, 3.38, and 3.67, respectively) when compared to the l/m ratio obtained for 3 (2.95), is due to a limited range of solvents in which the AN + DN mechanism is operative. This view is supported by the multiple regression analysis of 3 in the same 18 solvents used for 1, where an AN + DN mechanism is proposed, which yields l = 1.96 ± 0.14, m = 0.49 ± 0.05, R = 0.965, F-test = 101, and c = 0.23 ± 0.07 such that the l/m ratio for 3 is 4.00.

As shown in Table 1, the nucleophilicity (NT) values for the four aqueous TFE solvents range from a very low value of −3.30 in 97% TFE (w/w), to −1.73 in 50% TFE (w/w), while the ionizing power values (YCl) vary only slightly (2.83–3.16). A plot of log (k/k0)1 against NT in these four solvents results in a slope (l) = 0.72 ± 0.22 (0.08 probability that the term is statistically insignificant), R = 0.919, F-test = 11, and c = 0.51 ± 0.54. This l value is within the magnitude seen in aqueous fluoroalcohols for other alkyl chloroformate esters that undergo an ionization mechanism with strong rear-side solvation of the resonance-stabilized intermediate (Table 3).

In Table 4, the methanolysis and ethanolysis specifc rate order is shown to be kMeOCOCl > kEtOCOCl ≈ kn-PrOCOCl ≈ kiBuOCOCl ≈ kOctOCOCl > kiPrOCOCl. As previously pointed out and shown in Figure 1, the presence of an additional carbon in the 3-D image of iBuOCOCl (1'), pushs the isopropyl group out of the plane of the ether oxygen. As a result, access to the carbonyl carbon in iBuOCOCl (1') is not hindered by the presence of a branching alkyl group (1', Figure 1), and the observed rate order in EtOH and MeOH (Table 4) suggests that any steric or inductive or hyperconjugative effect due to the presence of the isobutyl group in 1 is, at best, negligible. On the other hand, the inductive effect and competing hyperconjugative release of the isopropyl group in 5 does have an impact on its rates of ethanolysis and methanolysis.

Table 4: A comparison of the specific rates of solvolysis of MeOCOCl, EtOCOCl, n-PrOCOCl, iPrOCOCl, iBuOCOCl, and n-OctOCOCl in common solvents at 25.0 °C.

| Solvent |

MeOCOCl

105 k (s−1)a |

EtOCOCl

105 k (s−1)b |

n-PrOCOCl

105 k (s−1)c |

iPrOCOCl

105 k (s−1)d |

iBuOCOCl

105 k (s−1)e |

n-OctOCOCl

105 k (s−1)f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% MeOH | 15.6 | 8.24 | 8.88 | 4.19 | 9.89 | 8.51 |

| 100% EtOH | 3.51 | 2.26 | 2.20 | 1.09 | 2.36 | 2.39 |

| 80% EtOH | 17.2 | 7.31 | 7.92 | 3.92 | 8.17 | 7.37 |

| 97% TFE | 0.023 | 0.062 | 12.3 | 0.086 | ||

| 70% TFE | 0.857 | 0.611 | 0.591 | 19.7 | 0.481 | |

aValue obtained using Arrhenius plots with the values reported at different temperatures in reference [67]. bRates are reported at 24.2 °C in reference [8]. cReference [10]. dReference [12]. eExtrapolated value obtained using Arrhenius plots with the values reported at different temperatures in Table 2. fReference [13].

Grunwald–Winstein analysis using Equation 1 for isobutyl chlorothioformate (2) in all 20 solvents studied (Table 1) resulted in l = 0.34 ± 0.18, m = 0.57 ± 0.13, R = 0.873, F-test = 27, and c = −0.11 ± 0.17. This scatter can be resolved by excluding the rate data for 2 in 100% EtOH, 90% EtOH, 100% MeOH, 90% MeOH, and 20% T-80% E. In the remaining 15 solvents, the correlation coefficient (R) improves significantly to 0.961, the F-test value rises to 73, l = 0.42 ± 0.13, m = 0.73 ± 0.09, and c = −0.37 ± 0.13 (Table 3). A plot of log (k/k0) for isobutyl chlorothioformate (2) against 0.42 NT + 0.73 YCl is shown in Figure 4 with the five deviating points included.

Figure 4: The plot of log (k/k0) for isobutyl chlorothioformate (2) against 0.42 NT + 0.73 YCl in 15 pure and binary solvents. The points for the 100% EtOH, 90% EtOH, 100% MeOH, 90% MeOH, and 20% T-80% E were not included in the correlation. They are added to show the extent of their deviation.

Figure 4: The plot of log (k/k0) for isobutyl chlorothioformate (2) against 0.42 NT + 0.73 YCl in 15 pure and...

The l/m ratio of 0.58 obtained for 2 in these 15 solvents is similar in magnitude to the previously observed ratios for methyl- (MeSCOCl) [15], ethyl- (EtSCOCl) [8], isopropyl- (iPrSCOCl) [16], and phenyl- (PhSCOCl) chlorothioformates [40,46,47] in solvents where an SN1 mechanism was said to be operative. The range of the l/m ratios, from 0.53 to 0.93, for these chlorothioformate esters (Table 3) is similar to the l/m ratio of 0.73 obtained for phenyl dithiochloroformate (4), the recommended standard for understanding ionization mechanisms in acyl containing systems.

Hence we suggest that in these 15 solvents, 2 solvolyzes by a dominant unimolecular ionization process with significant rear-side solvation of the developing acylium ion intermediate. For the five solvents (100% EtOH, 90% EtOH, 100% MeOH, 90% MeOH, and 20% T-80% E) whose data points lie above the regression line (Figure 4), a dominant superimposed addition–elimination mechanism (AN + DN) is proposed. The rate order shown in Table 5, of kMeSCOCl ≈ kEtSCOCl ≈ kiPrSCOCl ≈ kiBuSCOCl, is for the methanolysis and ethanolysis of these alkyl chlorothioformate esters at 25.0 °C. In pure methanol and ethanol a dominant association–dissociation (addition–elimination) mechanism, with rate-limiting addition, is believed to be effective in all four substrates. This rate order indicates that the inductive ability of the alkyl thioether group is almost independent of the type of alkyl group present. In Table 5, for solvolysis in the least nucleophilic and most highly ionizing solvent, 97% HFIP (w/w), a rate order of kMeSCOCl << kEtSCOCl < kiBuSCOCl << kiPrSCOCl is observed. This demonstrates that the hyperconjugative release during the formation of the developing resonance-stabilized carbocation intermediate is more efficient for isopropyl chlorothioformate (5) when compared to 2, as the presence of the additional carbon pushes the isopropyl group out of the plane of the thioether atom in 2' (Figure 1). This opinion is supported by an increase seen in the l/m ratio in the order of kMeSCOCl < kEtSCOCl < kiBuSCOCl < kiPrSCOCl.

Table 5: A comparison of the rates of solvolysis of MeSCOCl, EtSCOCl, iPrSCOCl, and iBuSCOCl, in selected common solvents at 25.0 °C.

| Solvent |

MeSCOCl

105 k (s−1)a |

EtSCOCl

105 k (s−1)b |

iPrSCOCl

105 k (s−1)c |

iBuSCOCl

105 k (s−1)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% MeOH | 2.00 | 2.15 | 1.99 | 2.27 |

| 100% EtOH | 0.884 | 0.430 | 1.21 | 1.01 |

| 80% EtOH | 2.44 | 2.68 | 13.7 | 2.99 |

| 97% TFE | 0.986 | 5.98 | 49.8 | 6.01 |

| 90% TFE | 1.92 | 10.2 | 69.5 | 11.7 |

| 70% TFE | 13.9 | 54.3 | 212 | 40.8 |

| 97% HFIP | 3.21 | 39.2 | 376 | 66.0 |

| 90% HFIP | 3.48 | 36.1 | 437 | 48.2 |

| 70% HFIP | 13.9 | 81.3 | 659 | 78.4 |

aReference [15]. bRates are reported at 24.2 °C in reference [8]. cReference [16]. dSee Table 1.

As shown from Table 4 and Table 5, the kiBuSCOCl < kiBuOCOCl rate order applies in methanol and ethanol where the addition–elimination mechanism is dominant. This is due to the inductive ability of the isobutoxy group being much greater than that of the corresponding sulfur analog. The observed rate order is completely reversed in 97% TFE (aqueous) to kiBuSCOCl >> kiBuOCOCl, where 2 is a 100-fold faster than 1. In the highly ionizing fluoroalcohols an ionization mechanism (SN1) is proposed to prevail for both substrates: This rate order signifies that the hyperconjugative release from the sulfur atom in 2 to the developing acylium ion is the dominant factor.

Conclusion

Correlation analysis of the solvolysis of isobutyl chloroformate (1) and isobutyl chlorothioformate (2) in a variety of pure and binary aqueous organic solvents was successfully analyzed using the extended Grunwald–Winstein equation (Equation 1). In both compounds side-by-side addition–elimination (with a rate-determining addition step) and unimolecular SN1 type mechanisms are believed to be possible.

In a majority of the solvents studied it is proposed that 1 solvolyzes by a bimolecular addition–elimination (AN + DN) process due to the inductive ability of the isobutoxy group, whereas in the four aqueous TFE mixtures a predominant unimolecular SN1 mechanism with rear-side solvation of the developing carbocation is suggested.

For 2, due to a more proficient hyperconjugative release, a dominant unimolecular ionization (SN1) mechanism with strong rear-side nucleophilic solvation is proposed for all solvents except 100% EtOH, 90% EtOH, 100% MeOH, 90% MeOH, and 20% T-80% E. In these five solvents an AN + DN process is believed to dominate.

Experimental

The isobutyl chloroformate (98%, Sigma-Aldrich) and isobutyl chlorothioformate (96%, Sigma-Aldrich) were used as received. Solvents were purified and the kinetic runs carried out as previously described [5,39]. A substrate concentration of approximately 0.005 M in a variety of solvents was employed. The specific rates and associated standard deviations, as presented in Table 1, were obtained by averaging all of the values from duplicate runs.

Multiple regression analyses were carried out using the Excel 2007 package from the Microsoft Corporation. The 3-D-views presented in Figure 1, were generated using the KnowItAll® Informatics System, ADME/Tox Edition, from BioRad Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA.

Acknowledgements

The research in the USA was supported by grant number 2 P2O RR016472-010 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) grant to the state of Delaware (DE) was obtained under the leadership of the University of Delaware, and the authors sincerely appreciate their efforts. Matthew J. McAneny completed a part of this research under the direction of Dr. Malcolm J. D’Souza as an undergraduate research assistant in the DE-INBRE sponsored Wesley College Directed Research Program.

References

-

Qiu, Y.-L.; Phan, T.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Or, S. Bicyclic Macrolide Derivatives. U.S. Patent 6,790,835 B1, Sept 14, 2004.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jones, J. The Chemical Synthesis of Peptides; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1991.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kevill, D. N. Chloroformate Esters and Related Compounds. In The Chemistry of the Functional Groups: The Chemistry of Acyl Halides; Patai, S., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp 381–453.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Matzner, M.; Kurkjy, R. P.; Cotter, R. J. Chem. Rev. 1964, 64, 645–687. doi:10.1021/cr60232a004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kevill, D. N.; Kyong, J. B.; Weitl, F. L. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4304–4311. doi:10.1021/jo00301a019

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Kyong, J. B.; Suk, Y. J.; Kevill, D. N. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 3425–3432. doi:10.1021/jo0207426

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Kevill, D. N.; Kim, J. C.; Kyong, J. B. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1999, 150–151. doi:10.1039/A808929I

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] -

Koh, H. J.; Kang, S. J.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2010, 31, 835–839. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2010.31.04.835

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kyong, J. B.; Won, H.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2005, 6, 87–96. doi:10.3390/i6010087

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Kyong, J. B.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 662–664.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

D'Souza, M. J.; Reed, D. N.; Erdman, K. J.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 862–879. doi:10.3390/ijms10030862

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2002, 240–243. doi:10.1039/b109169g

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

D’Souza, M. J.; Carter, S. E.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 1161–1174. doi:10.3390/ijms12021161

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

D'Souza, M. J.; Hailey, S. M.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2253–2266. doi:10.3390/ijms11052253

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

D’Souza, M. J.; Mahon, B. P.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2597–2611. doi:10.3390/ijms11072597

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res. 2008, 61–66. doi:10.3184/030823408X293189

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] -

Winstein, S.; Grunwald, E.; Jones, H. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 2700–2707. doi:10.1021/ja01150a078

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grunwald, E.; Winstein, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 846–854. doi:10.1021/ja01182a117

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kevill, D. N.; Anderson, S. W. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 1845–1850. doi:10.1021/jo00005a034

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kevill, D. N. Development and Uses of Scales of Solvent Nucleophilicity. In Advances in Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships; Charton, M., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1996; Vol. 1, pp 81–115.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bentley, T. W.; Carter, G. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 5741–5747. doi:10.1021/ja00385a031

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bentley, T. W.; Llewellyn, G. Prog. Phys. Org. Chem. 1990, 17, 121–158. doi:10.1002/9780470171967.ch5

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1993, 174–175.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kevill, D. N.; Ryu, Z. H. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2006, 7, 451–455. doi:10.3390/i7100451

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kevill, D. N.; Ismail, N. H.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 6303–6312. doi:10.1021/jo00100a036

Return to citation in text: [1] -

D'Souza, M. J.; Darrington, A. M.; Kevill, D. N. Org. Chem. Int. 2010, No. 130506. doi:10.1155/2010/130506

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010, 14, 1037–1049.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, I. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1972, 16, 334–340.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bentley, T. W. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6251–6257. doi:10.1021/jo800841g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Silvia, C. J.; True, N. S.; Bohn, R. K. J. Phys. Chem. 1978, 82, 483–488. doi:10.1021/j100493a023

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, Q.; Krisak, R.; Hagen, K. J. Mol. Struct. 1995, 346, 13–19. doi:10.1016/0022-2860(94)08420-M

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gobbato, K. I.; Della Védova, C. O.; Mack, H.-G.; Oberhammer, H. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 6152–6157. doi:10.1021/ic960536e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

So, S. P. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 1998, 168, 217–225. doi:10.1016/0166-1280(88)80356-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ulic, S. E.; Coyanis, E. M.; Romano, R. M.; Della Védova, C. O. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 1998, 54, 695–705. doi:10.1016/S1386-1425(98)00002-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Romano, R. M.; Della Védova, C. O.; Downs, A. J.; Parsons, S.; Smith, S. New J. Chem. 2003, 27, 514–519. doi:10.1039/b209005h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Erben, M. F.; Della Védova, C. O.; Boese, R.; Willner, H.; Oberhammer, H. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 699–706. doi:10.1021/jp036966p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Silvia, C. J.; True, N. S.; Bohn, R. K. J. Mol. Struct. 1979, 51, 163–170. doi:10.1016/0022-2860(79)80290-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1997, 1721–1724. doi:10.1039/a701140g

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Kevill, D. N.; Koyoshi, F.; D’Souza, M. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 346–362. doi:10.3390/i8040346

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

D’Souza, M. J.; Reed, D.; Koyoshi, F.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 788–796. doi:10.3390/i8080788

Return to citation in text: [1] -

D’Souza, M. J.; Shuman, K. E.; Carter, S. E.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 2231–2242. doi:10.3390/ijms9112231

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, K. H.; Kyong, J. B.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 1267–1270.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kyong, J. B.; Park, B.-C.; Kim, C.-B.; Kevill, D. N. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 8051–8058. doi:10.1021/jo005630y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. Can. J. Chem. 1999, 77, 1118–1122.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kevill, D. N.; Hailey, S. M.; Mahon, B. P.; D'Souza, M. J. Mechanistic Trends Observed with Sulfur-for-Oxygen Substitution in Chloroformate Esters. Faraday Discussion 145: Frontiers in Physical Organic Chemistry; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cardiff, 2009; pp 563 ff.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kevill, D. N.; Bond, M. W.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7869–7871. doi:10.1021/jo970657b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Koo, I. S.; Yang, K.; Kang, D. H.; Park, H. J.; Kang, K.; Lee, I. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 1999, 20, 577–580.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

An, S. K.; Yang, J. S.; Cho, J. M.; Yang, K.; Lee, J. P.; Bentley, T. W.; Lee, I.; Koo, I. S. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2002, 23, 1445–1450. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2002.23.10.1445

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leimu, R. Chem. Ber. 1937, 70 B, 1040–1053.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Crunden, E. W.; Hudson, R. F. J. Chem. Soc. 1961, 3748–3755. doi:10.1039/jr9610003748

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hudson, R. F.; Green, M. J. Chem. Soc. 1962, 1055–1061. doi:10.1039/jr9620001055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Green, M.; Hudson, R. F. J. Chem. Soc. 1962, 1076–1080. doi:10.1039/jr9620001076

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Queen, A. Can. J. Chem. 1967, 45, 1619–1629.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Queen, A.; Nour, T. A.; Paddon-Row, M. N.; Preston, K. Can. J. Chem. 1970, 48, 522–527.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

McKinnon, D. M.; Queen, A. Can. J. Chem. 1972, 50, 1401–1406.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

La, S.; Koh, K. S.; Lee, I. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1980, 24, 1–7.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

La, S.; Koh, K. S.; Lee, I. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1980, 24, 8–14.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Orlov, S. I.; Chimishkyan, A. L.; Grabarnik, M. S. J. Org. Chem. USSR (Engl. Transl.) 1983, 19, 1981–1987.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castro, E. A. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 3505–3524. doi:10.1021/cr990001d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castro, E. A.; Cubillos, M.; Santos, J. G. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 4802–4807. doi:10.1021/jo049559y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castro, E. A.; Aliaga, M.; Gazitúa, M.; Santos, J. G. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 4863–4869. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.03.013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castro, E. A. J. Sulfur Chem. 2007, 28, 401–429. doi:10.1080/17415990701415718

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castro, E. A.; Aliaga, M.; Campodonico, P. R.; Leis, J. R.; García-Río, L.; Santos, J. G. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2008, 21, 102–107. doi:10.1002/poc.1286

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castro, E. A.; Gazitúa, M.; Santos, J. G. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2009, 22, 1030–1037. doi:10.1002/poc.1555

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Digenis, G. A.; Agha, B. J.; Tsuji, K.; Kato, M.; Shinogi, M. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29, 1468–1476. doi:10.1021/jm00158a025

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seong, M. H.; Choi, S. H.; Lee, Y.-W.; Kyong, J. B.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2009, 30, 2408–2412. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2009.30.10.2408

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bentley, T. W.; Harris, H. C.; Zoon, H.-R.; Gui, T. L.; Dae, D. S.; Szajda, S. R. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 8963–8970. doi:10.1021/jo0514366

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 50. | Leimu, R. Chem. Ber. 1937, 70 B, 1040–1053. |

| 51. | Crunden, E. W.; Hudson, R. F. J. Chem. Soc. 1961, 3748–3755. doi:10.1039/jr9610003748 |

| 52. | Hudson, R. F.; Green, M. J. Chem. Soc. 1962, 1055–1061. doi:10.1039/jr9620001055 |

| 53. | Green, M.; Hudson, R. F. J. Chem. Soc. 1962, 1076–1080. doi:10.1039/jr9620001076 |

| 54. | Queen, A. Can. J. Chem. 1967, 45, 1619–1629. |

| 55. | Queen, A.; Nour, T. A.; Paddon-Row, M. N.; Preston, K. Can. J. Chem. 1970, 48, 522–527. |

| 56. | McKinnon, D. M.; Queen, A. Can. J. Chem. 1972, 50, 1401–1406. |

| 57. | La, S.; Koh, K. S.; Lee, I. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1980, 24, 1–7. |

| 58. | La, S.; Koh, K. S.; Lee, I. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1980, 24, 8–14. |

| 59. | Orlov, S. I.; Chimishkyan, A. L.; Grabarnik, M. S. J. Org. Chem. USSR (Engl. Transl.) 1983, 19, 1981–1987. |

| 54. | Queen, A. Can. J. Chem. 1967, 45, 1619–1629. |

| 55. | Queen, A.; Nour, T. A.; Paddon-Row, M. N.; Preston, K. Can. J. Chem. 1970, 48, 522–527. |

| 60. | Castro, E. A. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 3505–3524. doi:10.1021/cr990001d |

| 61. | Castro, E. A.; Cubillos, M.; Santos, J. G. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 4802–4807. doi:10.1021/jo049559y |

| 62. | Castro, E. A.; Aliaga, M.; Gazitúa, M.; Santos, J. G. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 4863–4869. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.03.013 |

| 63. | Castro, E. A. J. Sulfur Chem. 2007, 28, 401–429. doi:10.1080/17415990701415718 |

| 64. | Castro, E. A.; Aliaga, M.; Campodonico, P. R.; Leis, J. R.; García-Río, L.; Santos, J. G. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2008, 21, 102–107. doi:10.1002/poc.1286 |

| 65. | Castro, E. A.; Gazitúa, M.; Santos, J. G. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2009, 22, 1030–1037. doi:10.1002/poc.1555 |

| 7. | Kevill, D. N.; Kim, J. C.; Kyong, J. B. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1999, 150–151. doi:10.1039/A808929I |

| 8. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270 |

| 39. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1997, 1721–1724. doi:10.1039/a701140g |

| 40. | Kevill, D. N.; Koyoshi, F.; D’Souza, M. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 346–362. doi:10.3390/i8040346 |

| 68. | Bentley, T. W.; Harris, H. C.; Zoon, H.-R.; Gui, T. L.; Dae, D. S.; Szajda, S. R. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 8963–8970. doi:10.1021/jo0514366 |

| 22. | Bentley, T. W.; Carter, G. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 5741–5747. doi:10.1021/ja00385a031 |

| 23. | Bentley, T. W.; Llewellyn, G. Prog. Phys. Org. Chem. 1990, 17, 121–158. doi:10.1002/9780470171967.ch5 |

| 24. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1993, 174–175. |

| 25. | Kevill, D. N.; Ryu, Z. H. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2006, 7, 451–455. doi:10.3390/i7100451 |

| 67. | Seong, M. H.; Choi, S. H.; Lee, Y.-W.; Kyong, J. B.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2009, 30, 2408–2412. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2009.30.10.2408 |

| 66. | Digenis, G. A.; Agha, B. J.; Tsuji, K.; Kato, M.; Shinogi, M. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29, 1468–1476. doi:10.1021/jm00158a025 |

| 20. | Kevill, D. N.; Anderson, S. W. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 1845–1850. doi:10.1021/jo00005a034 |

| 21. | Kevill, D. N. Development and Uses of Scales of Solvent Nucleophilicity. In Advances in Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships; Charton, M., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1996; Vol. 1, pp 81–115. |

| 10. | Kyong, J. B.; Won, H.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2005, 6, 87–96. doi:10.3390/i6010087 |

| 7. | Kevill, D. N.; Kim, J. C.; Kyong, J. B. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1999, 150–151. doi:10.1039/A808929I |

| 8. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270 |

| 10. | Kyong, J. B.; Won, H.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2005, 6, 87–96. doi:10.3390/i6010087 |

| 11. | Kyong, J. B.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 662–664. |

| 12. | D'Souza, M. J.; Reed, D. N.; Erdman, K. J.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 862–879. doi:10.3390/ijms10030862 |

| 14. | D’Souza, M. J.; Carter, S. E.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 1161–1174. doi:10.3390/ijms12021161 |

| 67. | Seong, M. H.; Choi, S. H.; Lee, Y.-W.; Kyong, J. B.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2009, 30, 2408–2412. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2009.30.10.2408 |

| 12. | D'Souza, M. J.; Reed, D. N.; Erdman, K. J.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 862–879. doi:10.3390/ijms10030862 |

| 14. | D’Souza, M. J.; Carter, S. E.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 1161–1174. doi:10.3390/ijms12021161 |

| 5. | Kevill, D. N.; Kyong, J. B.; Weitl, F. L. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4304–4311. doi:10.1021/jo00301a019 |

| 6. | Kyong, J. B.; Suk, Y. J.; Kevill, D. N. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 3425–3432. doi:10.1021/jo0207426 |

| 5. | Kevill, D. N.; Kyong, J. B.; Weitl, F. L. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4304–4311. doi:10.1021/jo00301a019 |

| 6. | Kyong, J. B.; Suk, Y. J.; Kevill, D. N. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 3425–3432. doi:10.1021/jo0207426 |

| 11. | Kyong, J. B.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 662–664. |

| 12. | D'Souza, M. J.; Reed, D. N.; Erdman, K. J.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 862–879. doi:10.3390/ijms10030862 |

| 14. | D’Souza, M. J.; Carter, S. E.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 1161–1174. doi:10.3390/ijms12021161 |

| 11. | Kyong, J. B.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 662–664. |

| 12. | D'Souza, M. J.; Reed, D. N.; Erdman, K. J.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 862–879. doi:10.3390/ijms10030862 |

| 10. | Kyong, J. B.; Won, H.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2005, 6, 87–96. doi:10.3390/i6010087 |

| 12. | D'Souza, M. J.; Reed, D. N.; Erdman, K. J.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 862–879. doi:10.3390/ijms10030862 |

| 8. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270 |

| 1. | Qiu, Y.-L.; Phan, T.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Or, S. Bicyclic Macrolide Derivatives. U.S. Patent 6,790,835 B1, Sept 14, 2004. |

| 2. | Jones, J. The Chemical Synthesis of Peptides; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1991. |

| 3. | Kevill, D. N. Chloroformate Esters and Related Compounds. In The Chemistry of the Functional Groups: The Chemistry of Acyl Halides; Patai, S., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp 381–453. |

| 4. | Matzner, M.; Kurkjy, R. P.; Cotter, R. J. Chem. Rev. 1964, 64, 645–687. doi:10.1021/cr60232a004 |

| 9. | Koh, H. J.; Kang, S. J.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2010, 31, 835–839. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2010.31.04.835 |

| 22. | Bentley, T. W.; Carter, G. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 5741–5747. doi:10.1021/ja00385a031 |

| 23. | Bentley, T. W.; Llewellyn, G. Prog. Phys. Org. Chem. 1990, 17, 121–158. doi:10.1002/9780470171967.ch5 |

| 24. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1993, 174–175. |

| 25. | Kevill, D. N.; Ryu, Z. H. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2006, 7, 451–455. doi:10.3390/i7100451 |

| 8. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270 |

| 8. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270 |

| 26. | Kevill, D. N.; Ismail, N. H.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 6303–6312. doi:10.1021/jo00100a036 |

| 27. | D'Souza, M. J.; Darrington, A. M.; Kevill, D. N. Org. Chem. Int. 2010, No. 130506. doi:10.1155/2010/130506 |

| 28. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010, 14, 1037–1049. |

| 7. | Kevill, D. N.; Kim, J. C.; Kyong, J. B. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1999, 150–151. doi:10.1039/A808929I |

| 17. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res. 2008, 61–66. doi:10.3184/030823408X293189 |

| 18. | Winstein, S.; Grunwald, E.; Jones, H. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 2700–2707. doi:10.1021/ja01150a078 |

| 19. | Grunwald, E.; Winstein, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 846–854. doi:10.1021/ja01182a117 |

| 40. | Kevill, D. N.; Koyoshi, F.; D’Souza, M. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 346–362. doi:10.3390/i8040346 |

| 46. | Kevill, D. N.; Hailey, S. M.; Mahon, B. P.; D'Souza, M. J. Mechanistic Trends Observed with Sulfur-for-Oxygen Substitution in Chloroformate Esters. Faraday Discussion 145: Frontiers in Physical Organic Chemistry; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cardiff, 2009; pp 563 ff. |

| 47. | Kevill, D. N.; Bond, M. W.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7869–7871. doi:10.1021/jo970657b |

| 5. | Kevill, D. N.; Kyong, J. B.; Weitl, F. L. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4304–4311. doi:10.1021/jo00301a019 |

| 6. | Kyong, J. B.; Suk, Y. J.; Kevill, D. N. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 3425–3432. doi:10.1021/jo0207426 |

| 20. | Kevill, D. N.; Anderson, S. W. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 1845–1850. doi:10.1021/jo00005a034 |

| 21. | Kevill, D. N. Development and Uses of Scales of Solvent Nucleophilicity. In Advances in Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships; Charton, M., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1996; Vol. 1, pp 81–115. |

| 15. | D'Souza, M. J.; Hailey, S. M.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2253–2266. doi:10.3390/ijms11052253 |

| 14. | D’Souza, M. J.; Carter, S. E.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 1161–1174. doi:10.3390/ijms12021161 |

| 8. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270 |

| 8. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270 |

| 13. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2002, 240–243. doi:10.1039/b109169g |

| 16. | D’Souza, M. J.; Mahon, B. P.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2597–2611. doi:10.3390/ijms11072597 |

| 16. | D’Souza, M. J.; Mahon, B. P.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2597–2611. doi:10.3390/ijms11072597 |

| 11. | Kyong, J. B.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 662–664. |

| 12. | D'Souza, M. J.; Reed, D. N.; Erdman, K. J.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 862–879. doi:10.3390/ijms10030862 |

| 13. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2002, 240–243. doi:10.1039/b109169g |

| 10. | Kyong, J. B.; Won, H.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2005, 6, 87–96. doi:10.3390/i6010087 |

| 15. | D'Souza, M. J.; Hailey, S. M.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2253–2266. doi:10.3390/ijms11052253 |

| 15. | D'Souza, M. J.; Hailey, S. M.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2253–2266. doi:10.3390/ijms11052253 |

| 3. | Kevill, D. N. Chloroformate Esters and Related Compounds. In The Chemistry of the Functional Groups: The Chemistry of Acyl Halides; Patai, S., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp 381–453. |

| 31. | Silvia, C. J.; True, N. S.; Bohn, R. K. J. Phys. Chem. 1978, 82, 483–488. doi:10.1021/j100493a023 |

| 32. | Shen, Q.; Krisak, R.; Hagen, K. J. Mol. Struct. 1995, 346, 13–19. doi:10.1016/0022-2860(94)08420-M |

| 33. | Gobbato, K. I.; Della Védova, C. O.; Mack, H.-G.; Oberhammer, H. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 6152–6157. doi:10.1021/ic960536e |

| 34. | So, S. P. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 1998, 168, 217–225. doi:10.1016/0166-1280(88)80356-7 |

| 35. | Ulic, S. E.; Coyanis, E. M.; Romano, R. M.; Della Védova, C. O. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 1998, 54, 695–705. doi:10.1016/S1386-1425(98)00002-X |

| 36. | Romano, R. M.; Della Védova, C. O.; Downs, A. J.; Parsons, S.; Smith, S. New J. Chem. 2003, 27, 514–519. doi:10.1039/b209005h |

| 37. | Erben, M. F.; Della Védova, C. O.; Boese, R.; Willner, H.; Oberhammer, H. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 699–706. doi:10.1021/jp036966p |

| 38. | Silvia, C. J.; True, N. S.; Bohn, R. K. J. Mol. Struct. 1979, 51, 163–170. doi:10.1016/0022-2860(79)80290-2 |

| 16. | D’Souza, M. J.; Mahon, B. P.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2597–2611. doi:10.3390/ijms11072597 |

| 5. | Kevill, D. N.; Kyong, J. B.; Weitl, F. L. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4304–4311. doi:10.1021/jo00301a019 |

| 39. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1997, 1721–1724. doi:10.1039/a701140g |

| 17. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res. 2008, 61–66. doi:10.3184/030823408X293189 |

| 17. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res. 2008, 61–66. doi:10.3184/030823408X293189 |

| 17. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res. 2008, 61–66. doi:10.3184/030823408X293189 |

| 40. | Kevill, D. N.; Koyoshi, F.; D’Souza, M. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 346–362. doi:10.3390/i8040346 |

| 45. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. Can. J. Chem. 1999, 77, 1118–1122. |

| 40. | Kevill, D. N.; Koyoshi, F.; D’Souza, M. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 346–362. doi:10.3390/i8040346 |

| 45. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. Can. J. Chem. 1999, 77, 1118–1122. |

| 17. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res. 2008, 61–66. doi:10.3184/030823408X293189 |

| 17. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res. 2008, 61–66. doi:10.3184/030823408X293189 |

| 39. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1997, 1721–1724. doi:10.1039/a701140g |

| 40. | Kevill, D. N.; Koyoshi, F.; D’Souza, M. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 346–362. doi:10.3390/i8040346 |

| 17. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Res. 2008, 61–66. doi:10.3184/030823408X293189 |

| 5. | Kevill, D. N.; Kyong, J. B.; Weitl, F. L. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4304–4311. doi:10.1021/jo00301a019 |

| 6. | Kyong, J. B.; Suk, Y. J.; Kevill, D. N. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 3425–3432. doi:10.1021/jo0207426 |

| 7. | Kevill, D. N.; Kim, J. C.; Kyong, J. B. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1999, 150–151. doi:10.1039/A808929I |

| 8. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2120–2124. doi:10.1021/jo9714270 |

| 10. | Kyong, J. B.; Won, H.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2005, 6, 87–96. doi:10.3390/i6010087 |

| 11. | Kyong, J. B.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, D. K.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 662–664. |

| 13. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2002, 240–243. doi:10.1039/b109169g |

| 39. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1997, 1721–1724. doi:10.1039/a701140g |

| 40. | Kevill, D. N.; Koyoshi, F.; D’Souza, M. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 346–362. doi:10.3390/i8040346 |

| 41. | D’Souza, M. J.; Reed, D.; Koyoshi, F.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 788–796. doi:10.3390/i8080788 |

| 42. | D’Souza, M. J.; Shuman, K. E.; Carter, S. E.; Kevill, D. N. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 2231–2242. doi:10.3390/ijms9112231 |

| 43. | Park, K. H.; Kyong, J. B.; Kevill, D. N. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000, 21, 1267–1270. |

| 44. | Kyong, J. B.; Park, B.-C.; Kim, C.-B.; Kevill, D. N. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 8051–8058. doi:10.1021/jo005630y |

| 45. | Kevill, D. N.; D’Souza, M. J. Can. J. Chem. 1999, 77, 1118–1122. |

| 46. | Kevill, D. N.; Hailey, S. M.; Mahon, B. P.; D'Souza, M. J. Mechanistic Trends Observed with Sulfur-for-Oxygen Substitution in Chloroformate Esters. Faraday Discussion 145: Frontiers in Physical Organic Chemistry; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cardiff, 2009; pp 563 ff. |

| 47. | Kevill, D. N.; Bond, M. W.; D’Souza, M. J. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7869–7871. doi:10.1021/jo970657b |

| 48. | Koo, I. S.; Yang, K.; Kang, D. H.; Park, H. J.; Kang, K.; Lee, I. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 1999, 20, 577–580. |

| 49. | An, S. K.; Yang, J. S.; Cho, J. M.; Yang, K.; Lee, J. P.; Bentley, T. W.; Lee, I.; Koo, I. S. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2002, 23, 1445–1450. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2002.23.10.1445 |

© 2011 D’Souza et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)