Abstract

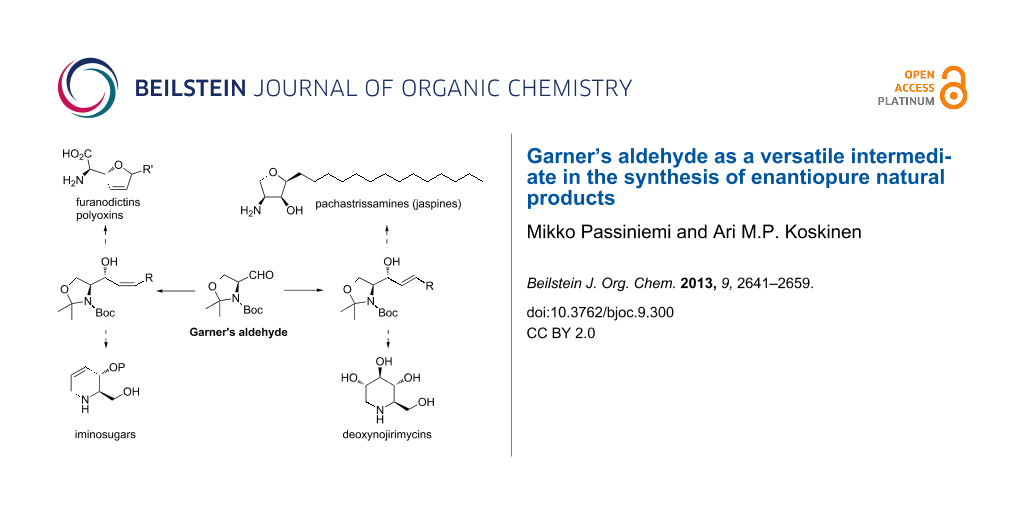

Since its introduction to the synthetic community in 1984, Garner’s aldehyde has gained substantial attention as a chiral intermediate for the synthesis of numerous amino alcohol derivatives. This review presents some of the most successful carbon chain elongation reactions, namely carbonyl alkylations and olefinations. The literature is reviewed with particular attention on understanding how to avoid the deleterious epimerization of the existing stereocenter in Garner’s aldehyde.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

“The universe is a dissymmetrical whole. I am inclined to think that life, as manifested to us, must be a function of the dissymmetry of the universe and of the consequences it produces. The universe is dissymmetrical; for, if the whole of the bodies which compose the solar system were placed before a glass moving with their individual movements, the image in the glass could not be superimposed on reality. Even the movement of solar life is dissymmetrical. A luminous ray never strikes in a straight line the leaf where vegetable life creates organic matter [...] Life is dominated by dissymmetrical actions. I can even foresee that all living species are primordially, in their structure, in their external forms, functions of cosmic dissymmetry.“ [1]

- Louis Pasteur

These visionary words were written over 100 years ago by Louis Pasteur. Little did he know how great of a challenge underlies these words. Natural products, secondary metabolites produced by living organisms, have their own distinct structures. Some of them have the same chemical structure, but differ from each other only by being mirror images (e.g., (R)(+)/(S)(−)-limonene and (S)(+)/(R)(–)-carvone, Figure 1). This sounds like an insignificant difference, but in reality enantiomers can have a totally different, even contradictory, effect on living organisms. As an example, (R)-limonene smells of oranges, whereas the (S)-enantiomer has a turpentine-like (with a lemon note) odor. The difference in physiological effects of enantiomers is of utmost importance especially for the pharmaceutical industry, but increasingly also in agrochemicals [2,3] and even in materials sciences, as evidenced by the introduction of chiral organic light emitting diodes [4,5]. In certain cases, one enantiomer may be harmful. This was the case, for example, with the drug thalidomide (Figure 1), the (R)-enantiomer of which was sold to pregnant women as a sedative and antiemetic in the 1960s. The (S)-enantiomer turned out to be teratogenic.

Figure 1: Structures of limonene, carvone and thalidomide.

Figure 1: Structures of limonene, carvone and thalidomide.

The crucial role of chirality presents a great challenge for synthetic chemists. Asymmetric synthetic methods have emerged and after the development of ample analytical methods over the last few decades, asymmetric synthesis has seen an exponential growth. This has allowed us to tackle even more challenging targets like palytoxin [6-8], vinblastine [9-14], and paclitaxel [15-23]. The field is still far from being mature, and there remains a huge demand for more advanced methods for the introduction of chirality to substrates.

This review presents a general overview of the synthesis and use of Garner’s aldehyde in natural product synthesis. Particular attention will be paid on the preservation of chiral information in the addition reaction of nucleophiles to the aldehyde. Models are presented for understanding the factors affecting the stability of the stereocenters, as well as those affecting diastereoselectivity in the generation of the new stereocenter.

Review

Philip Garner was the first to report a synthesis for 1,1-dimethylethyl 4-formyl-2,2-dimethyloxazolidine-3-carboxylate (1, Figure 2), today better known as Garner’s aldehyde [24,25]. This configurationally stable aldehyde has shown its power as a chiral building block in the synthesis of various natural products as well as their synthetic intermediates. It is one of the most cited chiral building blocks in recent times and has been used in over 600 publications.

Figure 2: Structure of Garner’s aldehyde.

Figure 2: Structure of Garner’s aldehyde.

Synthesis of Garner’s aldehyde

Garner’s aldehyde (1) has been widely used as an intermediate in multistep synthesis. Thus the synthesis of 1 has to meet some essential requirements: 1) easy and large scale preparation and 2) configurational and chemical stability of all intermediates.

In his original paper, Garner first protected the amino group with Boc anhydride in dioxane, then esterified the carboxylic acid with iodomethane under basic conditions in dimethylformamide (DMF) and finally formed the dimethyloxazolidine ring of 4 with catalytic p-toluenesulfonic acid and 2,2-dimethoxypropane (DMP) in refluxing benzene (Scheme 1) [24,25]. Reduction of the methyl ester 4 to aldehyde 1 was performed with DIBAL-H (175 mol %) at −78 °C. Garner later reported that they had detected some epimerization of the chiral center (5–7% loss of ee down to 93–95% ee) [26]. Another drawback of this route is the use of the toxic and carcinogenic iodomethane in the esterification reaction.

Scheme 1: (a) i) Boc2O, 1.0 N NaOH (pH >10), dioxane, +5 °C → rt; ii) MeI, K2CO3, DMF, 0 °C → rt (86% over two steps); (b) Me2C(OMe)2, cat. p-TsOH, benzene, reflux (70–89%); (c) 1.5 M DIBAL-H, toluene, −78 °C (76%).

Scheme 1: (a) i) Boc2O, 1.0 N NaOH (pH >10), dioxane, +5 °C → rt; ii) MeI, K2CO3, DMF, 0 °C → rt (86% over tw...

Since the first synthesis of aldehyde (S)-1 by Garner there have been many modifications and improvements to the synthesis of the enantiomers ((R)-1 and (S)-1). Modifications to the original synthesis have focused either on the reaction sequence (esterification first and then Boc protection) or on the reduction to aldehyde. Other groups have tried to improve the synthesis of the aldehyde. McKillop et al. found that the esterification reaction is performed best first with 235 mol % of HCl (formed in situ from the reaction of AcCl with MeOH) in MeOH [27]. The serine methyl ester hydrochloride salt was then protected with Boc anhydride. The N,O-acetal was formed using BF3·Et2O and DMP in acetone (Scheme 2). For the reduction they followed Garner’s procedure. This method allows an easy access to the fully protected methyl ester 4, but the problem of chiral degradation could not be solved (reported rotation −89 vs −91.7 in [26]).

Scheme 2: (a) AcCl, MeOH, 0 °C → reflux (99%); (b) i) (Boc)2O, Et3N, THF, 0 °C → rt → 50 °C (89%); ii) Me2C(OMe)2, BF3·Et2O, acetone, rt (91%).

Scheme 2: (a) AcCl, MeOH, 0 °C → reflux (99%); (b) i) (Boc)2O, Et3N, THF, 0 °C → rt → 50 °C (89%); ii) Me2C(O...

Dondoni adopted McKillop’s procedure for the preparation of 4 [28]. In order to reduce the loss of enantiopurity, they decided to follow Roush’s protocol [29] for the preparation of the aldehyde, i.e. reduction of 4 to alcohol 6 and oxidation of this alcohol to (S)-1. Moffatt–Swern oxidation provided the final aldehyde (S)-1 from the primary alcohol 6. In the standard Swern procedure the transformation of the activated alcohol intermediate to the final carbonyl compound (i.e. cleaving off the proton) is done by the addition of Et3N at cold temperatures (–78 to –60 °C). According to Roush, the use of triethylamine for this transformation led to partial racemization of 1 (85% ee). Dondoni noticed that changing the base to the bulkier base N,N-diisopropylethylamine (Hünig’s base, DIPEA) inhibits the epimerization (Scheme 3) [28]. With DIPEA as the base they could isolate the aldehyde (S)-1 with an enantiopurity of 96–98% ee. The drawback of this route is an additional reaction step, the “overreduction” of the ester 4 to alcohol 6 and the necessary re-oxidation to aldehyde 1.

Scheme 3: (a) LiAlH4, THF, rt (93–96%); (b) (COCl)2, DMSO, iPr2NEt, CH2Cl2, −78 °C → −55 °C (99%).

Scheme 3: (a) LiAlH4, THF, rt (93–96%); (b) (COCl)2, DMSO, iPr2NEt, CH2Cl2, −78 °C → −55 °C (99%).

As a conclusion of the above results we see that reversing the order of the two first reaction steps has a significant effect on the overall yield (from Garner’s 86% to Dondoni’s 94–98%). Less racemization can be observed with the reduction–oxidation sequence. Of course, other methods for the reduction can be used. The ester can be reduced to alcohol 6 (e.g., with NaBH4/LiCl) and then oxidized to 1 with non-basic methods (e.g., IBX/DMP [30] or TEMPO/NaOCl [31] to name a few), which will not epimerize the α-center.

For our synthesis of 1, we adopted a slightly modified sequence [32]. L-Serine (2) is first esterified under traditional Fischer conditions (Scheme 4). The hydrochloride 5 is N-protected using (Boc)2O. The acetonide is then introduced under mild Lewis acidic conditions to give the desired fully protected serine ester 4. This is reduced to the aldehyde 1 with DIBAL-H, while keeping the reaction temperature below −75 °C. This allowed us to isolate the aldehyde (S)-1 in 97% ee. This reaction sequence was performed in more than 1.0 mol scale starting from L-serine and the reduction to Garner’s aldehyde was performed on a 0.5 mol scale. DIBAL-H is an efficient reducing agent, but at times causes problems during work-up, especially in larger scale reactions. We, among others, have observed the gelatinous aluminium salts after the addition of an aqueous solution. Due to the formation of insoluble gel-like aluminium salts, the extraction procedure gets more challenging and sometimes a small portion of the substrate remains with the aluminium salts. Another drawback of DIBAL-H is the overreduction to alcohol 6. When only small amounts of the overreduced alcohol are present, one high vacuum distillation is enough to purify the crude aldehyde. When present in amounts greater than 10%, two high vacuum distillations are required. Pure aldehyde 1 crystallizes in the freezer and forms semi-transparent white crystals.

Scheme 4: The Koskinen procedure for the preparation of Garner’s aldehyde. (a) i) AcCl, MeOH, 0 °C → 50 °C (99%); ii) (Boc)2O, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → rt (95–99%); (b) Me2C(OMe)2, BF3·Et2O, CH2Cl2, rt (86%, after high vacuum distillation); (c) DIBAL-H, toluene, −84 °C (EtOAc/N2 bath) (82–84%, after high vacuum distillation).

Scheme 4: The Koskinen procedure for the preparation of Garner’s aldehyde. (a) i) AcCl, MeOH, 0 °C → 50 °C (9...

Our procedure provides Garner’s aldehyde (S)-1 in a 66–71% overall yield. The original Garner procedure provides (S)-1 in 46–58% and Dondoni’s in 75–85% yield. Dondoni did neither purify his intermediates (from 2 to (S)-1) nor the final product. They just reported that all of the products are >95% pure based on NMR analysis.

A very recent approach to the synthesis of Garner’s aldehyde was published by Burke and Clemens [33]. They reported that 1 could be synthesized by asymmetric formylation reaction from Funk’s achiral alkene (Scheme 5) [34]. The formylation reaction provided (R)-1 and (S)-1 in acceptable yields (71% and 70%, respectively) and excellent enantioselectivities (94% ee and 97% ee, respectively). However, this synthesis suffers from many drawbacks. Firstly, the synthesis of the Funk’s alkene commences from DL-serine and is a multistep sequence requiring Pb(OAc)4. DL-Serine costs 524 €/kg (Aldrich, June 2013 price) compared to L-serine’s 818 €/kg (Aldrich, June 2013). Secondly, both the formylation catalyst and bis(diazaphospholane) ligand are expensive and have to be used in large amounts. Thirdly, the formylation reaction was performed only in a 5 mmol scale and was not optimized for large scale synthesis.

Scheme 5: Burke’s synthesis of Garner’s aldehyde. BDP - bis(diazaphospholane).

Scheme 5: Burke’s synthesis of Garner’s aldehyde. BDP - bis(diazaphospholane).

Asymmetric induction with Garner’s aldehyde

Nucleophilic addition to Garner’s aldehyde gives an easy access to 2-amino-1,3-dihydroxypropyl substructures. This structural motif can be found in many natural products, such as iminosugars (7 and 9), peptide antibiotics (8), sphingosines and their derivatives (10 and 11, Figure 3). These naturally occurring polyhydroxylated compounds have attracted increasing interest from synthetic chemists, because they are frequently found to be potent inhibitors of many carbohydrate-processing enzymes involved in important biological systems. These unique molecules have tremendous potential as therapeutic agents in a wide range of diseases such as metabolic diseases (lysosomal storage disorders, diabetes), viral infections, tumour metastasis, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Figure 3: Structures of some iminosugars (7, 9), peptide antibiotics (8) and sphingosine (10) and pachastrissamine (11).

Figure 3: Structures of some iminosugars (7, 9), peptide antibiotics (8) and sphingosine (10) and pachastriss...

Through the addition of a nucleophile to the aldehyde (S)/(R)-1, a new C–C bond is formed, hence allowing carbon chain elongation and further functionalization. Nucleophilic addition of an alkyne to 1 gives access to propargylic alcohols of the structure A (Scheme 6). This alcohol can be selectively reduced either to cis- (B) or trans-allylic alcohol C. cis-Selective reduction of A can be achieved with Lindlar’s catalyst with H2 under atmospheric pressure. The thermodynamic trans-allylic alcohol C arises from the reaction of A with Red-Al. Both isomers B and C can also be directly accessed from 1 with the corresponding cis- and trans-vinyl nucleophiles. Allylic alcohol B can be used as an intermediate in the synthesis of various natural products or intermediates thereof. The cis-double bond allows cyclizations to five- or six-membered rings. Five-membered dihydrofuran rings lead to the synthesis of furanomycin D [35,36], norfuranomycin E [37], and the polyoxin family F [38]. The six-membered tetrahydropyridine G synthesized via this route can be used as an intermediate in the synthesis of iminosugars, e.g., of the deoxynojirimycin family H [39-43]. The trans-allylic alcohol C contains already the functional groups of sphingosines and depending on the stereochemistry at C2 and C3, the synthesis of all four isomers can be achieved [44-47]. Isomer C leads also to the synthesis of deoxynojirimycin family H [48]. Addition of an allylic nucleophile provides access to homoallylic alcohols I. These can be derivatized to unnatural amino acids, such as K [49] and L [50] or to aminosugar derivatives like M [29,51].

Scheme 6: Use of Garner’s aldehyde 1 in multistep synthesis.

Scheme 6: Use of Garner’s aldehyde 1 in multistep synthesis.

Additions of various nucleophiles to 1 have been summarized by Bols and co-workers in 2001 [52]. We have recently reviewed the literature on the synthesis of 1,2-vicinal amino alcohols [53]. Use of Garner’s aldehyde for the synthesis of non-natural amino acids through ethynylglycine has been reviewed [54]. In the following section, significant findings in the use of 1 as an electrophile and chiral intermediate will be discussed.

Addition of organometallic reagents to Garner’s aldehyde

The addition of a nucleophile to Garner’s aldehyde provides a facile access to 2-amino-1,3-dihydroxypropyl substructures. Through the addition of a carbon nucleophile also a new stereocenter is formed. Depending on the stereofacial selectivity, one can access either the anti-isomer 12 or syn-isomer 13 as the major product (Scheme 7). The high anti-selectivity can be rationalized with the attack of the nucleophile from the sterically least hindered side (re-side attack). The Felkin–Anh non-chelation transition state model explains this selectivity [55]. The nucleophile attacks not only from the least hindered side (substituent effects), but also from the side where the low-lying σ*C–N orbital is aligned parallel with the π- and π*-orbital of the carbonyl group, allowing delocalization of electron density from the reaction center toward nitrogen. In cases where syn-selectivity is observed, the Cram’s chelation control model provides an explanation [56,57]. Chelating metal coordinates between the two carbonyls (the aldehyde and the carbamate), thus forcing the nucleophile to attack from the si-side and affecting the selectivity with opposite stereocontrol [58].

Scheme 7: Explanation of the anti- and syn-selectivity in the nucleophilic addition reaction.

Scheme 7: Explanation of the anti- and syn-selectivity in the nucleophilic addition reaction.

In 1988, in pioneering work independently done by Herold [59] and Garner [44] investigated the use of chiral aminoaldehydes as intermediates for the synthesis of nitrogen containing natural products. Both groups realized that the nucleophilic addition of a lithiated alkynyl group to 1 in THF was selective, favouring the anti-adduct 14 (Scheme 8). Herold also noticed that the addition of hexamethylphosphorous triamide (HMPT) increased the selectivity from 8:1 (Garner) to >20:1 (anti/syn). HMPT co-ordinates to the Li-cation, thus breaking the lithium clusters. This increases the nucleophilicity of the alkyne and favours the kinetic anti-adduct 14. Through the use of chelating metals (ZnBr2 in Et2O [59]) Herold noticed a reversal in selectivity favouring the syn-adduct 15 (1:20 anti/syn). Garner used a slightly different method. He formed the nucleophile reductively from pentadecyne with iBu2AlH in THF [44]. This vinylalane provided the syn-adduct 16 in modest stereoselectivity (1:2 anti/syn).

Scheme 8: Herold’s method: (a) Lithium 1-pentadecyne, HMPT, THF, −78 °C (71%); (b) Lithium 1-pentadecyne, ZnBr2, Et2O, −78 °C → rt (87%). Garner’s method: (c) Lithium 1-pentadecyne, THF, −23 °C (83%); (d) 1-Pentadecyne, DIBAL-H, hexanes/toluene, −78 °C (>80%).

Scheme 8: Herold’s method: (a) Lithium 1-pentadecyne, HMPT, THF, −78 °C (71%); (b) Lithium 1-pentadecyne, ZnBr...

For the addition reaction to be feasible for asymmetric synthesis, the configurational integrity during this step is important. Garner and many others have demonstrated that there is practically no epimerization of the α-carbon center of 1 during the addition reaction [38]. While working on the synthesis of thymine polyoxin C, Garner coupled the lithium salt of ethyl propiolate with (R)-1 (Scheme 9) in HMPT/THF at −78 °C. The reaction was highly anti-selective (13:1 anti/syn) giving adduct 17 in a good yield (75%). The propargylic alcohol 17 was converted to the corresponding Mosher esters [60] 18 and 19. A careful NMR analysis indicated that there was less than 2% cross-contamination.

Scheme 9: (a) Ethyl lithiumpropiolate, HMPT, THF, −78 °C; (b) (S)- or (R)-MTPA, DCC, DMAP, THF, rt (18, 81%) or (19, 87%).

Scheme 9: (a) Ethyl lithiumpropiolate, HMPT, THF, −78 °C; (b) (S)- or (R)-MTPA, DCC, DMAP, THF, rt (18, 81%) ...

Since the first results of stereoselective additions by Herold and Garner, much attention has been paid on the factors influencing the stereoselectivity. Coleman and Carpenter studied the nucleophilic addition of vinyl organometallic reagents to (S)-1 (Scheme 10) [61]. They noticed that the addition of vinyllithium in THF provided the anti-adduct 20 in a moderate 5:1 anti/syn-selectivity. By changing the metal to magnesium (vinylMgBr) the selectivity slightly dropped to 3:1 (anti/syn) still favouring adduct 20. Addition of a Lewis acid (TiCl4) did not affect the diastereoselectivity with vinyllithium species. The addition of vinyllithium to (S)-1 in the presence of 100 mol % of TiCl4 in THF gave a 5:1 (anti/syn) mixture of adducts 20 and 21. Tetrahydrofuran coordinates quite strongly to Lewis acids, which increases the electron density at the metal atom. This lowers the metal atom’s ability to coordinate to other Lewis bases, such as the carbonyl group. By changing the solvent to a poorer donor (≈ less Lewis basic), one can alter the electron density brought about by the solvent molecules to the metal atom. With vinyllithium species in the presence of TiCl4 in Et2O or toluene, the anti-selectivity dropped to 3:1 and 2:1, respectively. Best syn-selectivities were achieved with vinylZnCl in Et2O (1:6 anti/syn). Coleman also noticed that the addition of excess ZnCl2 did not increase the syn-selectivity at all. They attributed this to the mono-coordination of the metal to the carbamate instead of the usual “bidentate” chelation control model (as shown in Scheme 10).

Scheme 10: Coleman’s selectivity studies and their transition state model for the co-ordinated delivery of the vinyl nucleophile.

Scheme 10: Coleman’s selectivity studies and their transition state model for the co-ordinated delivery of the...

Joullié observed that the more reactive Grignard reagents (e.g., PhMgBr or MeMgBr) give rise to kinetic anti-products via the non-chelation pathway [62]. Since these reagents are highly reactive, the reaction takes place before the metal has coordinated to any of the carbonyl groups, thus causing the Felkin–Anh control. When the steric bulk of the nucleophile was increased from PhMgBr to iPrMgBr the selectivity reversed from 5:1 anti/syn to 1:6 with iPrMgBr. A distinct solvent effect was also observed (Scheme 11). The selectivity obtained by Joullie for the reaction of 1 with PhMgBr was reversed for our system [63]. Joullié obtained a 5:1 (anti/syn) selectivity of alcohols 22 and 23 in THF compared to the 2:3 ratio observed in Et2O. This change in selectivity can be explained by diethyl ether being a less coordinating solvent [64].

Scheme 11: (a) PhMgBr, THF, −78 °C → 0 °C [62] or (a) PhMgBr, Et2O, 0 °C [63].

Scheme 11: (a) PhMgBr, THF, −78 °C → 0 °C [62] or (a) PhMgBr, Et2O, 0 °C [63].

Fürstner investigated the use of organorhodium nucleophiles with aldehydes (Scheme 12) [65]. They screened catalysts, ligands and bases in order to find the best conditions for the alkylation reaction. They found RhCl3·3H2O together with imidazolium chloride 26 as the ligand precursor and the base NaOMe to be the catalyst system of choice. NaOMe reacts with the ligand precursor 26 and forms an N-heterocyclic carbene. The method was tested also with Garner’s aldehyde and two different boronic acid derived nucleophiles (R = Ph or 1-octenyl). High anti-selectivity was observed. With the in situ formed phenyl nucleophile the selectivity was excellent >30:1 (anti/syn) giving 24 in a good yield (71%), but with the open chain alkene the selectivity eroded to 4.6:1 (anti/syn) giving 25 in 78% yield. The (E)-octenylboronic acid undergoes proto-deborylation at elevated temperatures, so the reaction had to be performed at 55 °C and with slightly higher catalyst loading (5% instead of the usual 3%).

Scheme 12: (a) cat. RhCl3·3H2O, cat. 26, NaOMe, Ph-B(OH)2, aq DME, 80 °C (24, 71%); (b) cat. RhCl3·3H2O, cat. 26, NaOMe, C6H13CH=CH2-B(OH)2, aq DME, 55 °C (25, 78%).

Scheme 12: (a) cat. RhCl3·3H2O, cat. 26, NaOMe, Ph-B(OH)2, aq DME, 80 °C (24, 71%); (b) cat. RhCl3·3H2O, cat. ...

Fujisawa studied the addition of lithiated dithiane to (S)-1 (Scheme 13) [66]. Without additives the reaction in THF provided alcohols 27 and 28 in a 7:3 ratio (anti/syn). Addition of aggregation braking HMPT slightly improved the selectivity (10:3). Almost complete selectivity was achieved when BF3·Et2O (6 equiv) and CuI (0.3 equiv) were used (>99:1 anti/syn). They reasoned that the high selectivity arose from the use of a monodentate Lewis acid and the highly dissociated anion derived from the organocopper species.

Scheme 13: Lithiated dithiane (3 equiv), CuI (0.3 equiv), BF3·Et2O (6 equiv), THF, −50 °C, 12 h (70%).

Scheme 13: Lithiated dithiane (3 equiv), CuI (0.3 equiv), BF3·Et2O (6 equiv), THF, −50 °C, 12 h (70%).

Recently Lam reported interesting results on the stereoselective addition of a lithiated alkynyl species to (S)-1 (Scheme 14) [67]. According to their results, temperature plays a crucial role on the outcome of the reaction. When the reaction was performed at –15 °C (1.36 equiv of alkyne and 1.16 equiv of n-BuLi), no anti-adduct 29 was detected, instead the syn-adduct 30 was obtained as the sole stereoisomer. By lowering the temperature to −40 °C and keeping the amount of reagents the same, the selectivity was inverted! Only the anti-adduct 29 was isolated. This change in selectivity was explained with two different transition states. At lower temperatures (−40 °C) under kinetic control the Felkin–Anh product is predominant. At higher temperatures (−15 °C) the nucleophilic addition occurs via a thermodynamically more stable transition state that resembles the chelation control TS. These results are interesting as this is the first time anyone reports a complete inversion of selectivity just by raising the reaction temperature. Decrease in anti-selectivity has been evidenced by others, when the reaction temperature has been raised by 40 to 100 °C (e.g., from −78 °C to rt), but never a total reverse. If these results are reliable, there has to be a total change in the transition state towards total chelation control and most likely also in the aggregation level of lithiated reagents.

Scheme 14: Addition reaction reported by Lam et al. (a) 1-Hexyne, n-BuLi, THF, −15 °C or −40 °C.

Scheme 14: Addition reaction reported by Lam et al. (a) 1-Hexyne, n-BuLi, THF, −15 °C or −40 °C.

Jurczak has investigated the effect of additives on the selectivity of the nucleophilic addition reaction in toluene [58]. When lithiated 31 was used as the nucleophile, their results were similar to Herold’s [59]. With HMPT as an additive they obtained a selectivity of 20:1 favouring the anti-allylic alcohol 32 (Scheme 15). Without additives the selectivity decreased to mere 3:1 (anti/syn). Under the same conditions but by raising the reaction temperature to rt the selectivity dropped further down to 3:2 (anti/syn). With chelating metals, such as Mg, Zn and Sn, the stereofacial preference changed from the re to the si side attack. The use of tin(IV) chloride as the chelating agent gave the highest syn-selectivities (>1:20 anti:syn), but poor yields. Slightly higher yields were achieved with ZnCl2 giving the syn-adduct 33 in 65% yield, but with lower selectivities (1:10).

Scheme 15: (a) n-BuLi, HMPT, toluene, −78 °C → rt (85%); (b) n-BuLi, ZnCl2, toluene/Et2O, −78 °C → rt (65%).

Scheme 15: (a) n-BuLi, HMPT, toluene, −78 °C → rt (85%); (b) n-BuLi, ZnCl2, toluene/Et2O, −78 °C → rt (65%).

The additions of propargylic alcohols 34 and 35 were also selective (Scheme 16). Mori performed the addition using unprotected alcohol 34 as nucleophile [68]. The selectivity at −40 °C was 4.2:1 favouring the anti-adduct 36. Bittman performed similar addition with 32 as the nucleophile at −78 °C [69]. The selectivity was 7.9:1 favouring the anti-adduct 37. In the same year Yadav did the same addition reaction with HMPT which raised the anti-selectivity to >20:1 (anti/syn) [70].

Scheme 16: (a) n-BuLi, 34, THF, −40 °C [69]; (b) n-BuLi, 35, THF, −78 °C → rt (80%) [70]; (c) n-BuLi, 35, HMPT, THF, −78 °C (87%) [71].

Scheme 16: (a) n-BuLi, 34, THF, −40 °C [69]; (b) n-BuLi, 35, THF, −78 °C → rt (80%) [70]; (c) n-BuLi, 35, HMPT, THF, −...

Chisholm has been looking for milder catalytic metal-alkyne nucleophiles for carbonyl 1,2-addition reactions, which wouldn’t enolize the labile α-protons next to a carbonyl group (Scheme 17) [71]. They found that a Rh(I)-catalyst with a monodentate electron rich phosphine ligand 42 formed a nucleophilic metal-acetylide with terminal alkynes, such as 40. The phosphine ligand had to be monodentate; bidentate ligands gave a lot lower yields. Their catalyst system worked very efficiently with many carbonyl electrophiles, also with Garner’s aldehyde (R)-1. The reaction of 1 with 40 gave 41 with high selectivity (>20:1 anti/syn) in good yield (74%). Unfortunately they do not discuss whether the substrate racemizes under these conditions.

Scheme 17: (a) cat. Rh(acac)(CO)2, 42, THF, 40 °C (74%).

Scheme 17: (a) cat. Rh(acac)(CO)2, 42, THF, 40 °C (74%).

Van der Donk has been interested in the synthesis of dehydro amino acids (Scheme 18) [72]. In two of their examples they used copper-acetylide nucleophiles, which led to high syn-selectivities. With propyneCuI the selectivity was 1:16 (anti/syn) providing the propargylic alcohol 43 in 95% yield. By changing the nucleophile to TMS-ethyneCuI the syn-selectivity increased to over 1:20, but providing the syn-adduct 44 in lower yield (82%). HPLC analysis showed that no epimerization had occurred. These results support Herold’s seminal work published 20 years earlier [59]. Reginato et al. coupled ethyne to Garner’s aldehyde (S)-1 under chelation control [73]. Surprisingly, a 1:1 (anti/syn) mixture of adducts 45 and 46 was obtained. Hanessian et al. have shown that also electron deficient acetylide nucleophiles can be used in the reaction [74]. After carefully studying the reaction conditions and various additives, they found ZnBr2 to be the best coordinating agent. The diastereoselectivity was good, favouring the syn-adduct 47 (1:12 anti/syn). The anti-selective addition of a lithiopropiolate to (R)-1 was presented by Garner already in 1990 [38].

Scheme 18: (a) 1-PropynylMgBr, CuI, THF, Me2S, −78 °C (95%); (b) Ethynyltrimethylsilane, EtMgBr, CuI, THF, Me2S, −78 °C (82%) [72]; (c) EthynylMgCl, ZnBr2, toluene, −78 °C [73]; (d) n-BuLi, methyl propiolate, Et2O, −78 °C → 0 °C, then (S)-1 at −20 °C (62%) [74].

Scheme 18: (a) 1-PropynylMgBr, CuI, THF, Me2S, −78 °C (95%); (b) Ethynyltrimethylsilane, EtMgBr, CuI, THF, Me2...

Soai et al. have examined the use of vinylzinc nucleophiles as alkenylating agents in the synthesis of D-erythro-sphingosine (Scheme 19) [45]. Treatment of (S)-1 with pentadecenyl(ethyl)zinc (48) in the presence of catalytic (R)-diphenyl(1-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl)methanol (50, (R)-DPMPM) [75] in toluene at 0 °C gave adducts 49 and 16 in a 4:1 ratio (anti/syn). By changing the chiral ligand to (S)-DPMPM 51 the selectivity dropped to 2:1 (anti/syn). When the addition reaction was performed in the presence of achiral N,N-dibutylaminoethanol 52 they obtained the highest selectivities (7.3:1 anti/syn). Despite performing the reaction seemingly under chelation control, the selectivity follows the Felkin–Anh transition state model. This selectivity arises from the use of metal coordinating N,O-ligands. These ligands affect both the reactivity of the metalated nucleophiles and also the metal’s capability of coordination.

Scheme 19: (a) cat. 50, toluene, 0 °C (52%); (b) cat. 51, toluene, 0 °C (51%); (c) cat. 52, toluene, 0 °C (50%).

Scheme 19: (a) cat. 50, toluene, 0 °C (52%); (b) cat. 51, toluene, 0 °C (51%); (c) cat. 52, toluene, 0 °C (50%...

Montgomery studied the nickel-catalyzed reductive additions of α-aminoaldehydes with silylalkynes (Scheme 20) [76]. The reduction of TMS-alkyne 53 was performed with a trialkylsilane and a Ni(COD)2 catalyst ligated with an in situ formed N-heterocyclic carbene. In all cases studied, they found both the anti/syn- and the Z/E-selectivity to be high (>20:1), but the chemical yield was varying. Highest yields (78–80%) were achieved with short alkyl chains (R = Me) or when R = phenyl. When the alkyl chain was lengthened (R = C13H27), while aiming for the synthesis of D-erythro-sphingosine, the yield drastically dropped to 18%. By changing the reaction conditions (2 equiv of (S)-1 with 1% water in THF) the yield increased to acceptable levels (65%) while the selectivity remained practically the same. They also tested the reaction with other serinal derivatives, but the best results were achieved with (S)-1.

Scheme 20: (a) (iPr)3SiH, cat. Ni(COD)2, dimesityleneimidazolium·HCl, t-BuOK, THF, rt.

Scheme 20: (a) (iPr)3SiH, cat. Ni(COD)2, dimesityleneimidazolium·HCl, t-BuOK, THF, rt.

Alkynes can be converted to (E)-vinyl nucleophiles through hydrozirconation. In view of the relatively low electronegativity (1.2–1.4) of Zr, which is roughly comparable with that of Mg and somewhat lower than that of Al, the low reactivity of organylzirconocene chlorides towards carbonyl compounds is puzzling. It is likely that the presence of two sterically demanding cyclopentadienyl (Cp) groups is at least partially responsible for their low reactivity. Suzuki noticed that Lewis acids promote C–C-bond forming reactions of organylzirconocene nucleophiles (Scheme 21) [77]. They used AgAsF6 as the Lewis acid promoter and found that also Garner’s aldehyde reacts under these conditions with 1-hexenylzirconocene. The reaction gave a good yield of the addition products 56 and 57 (70% combined yield), but no diastereoselectivity was observed. Peter Wipf has done pioneering work on the hydrozirconation–transmetallation sequence [78,79]. Murakami used this information when investigating the reaction of transmetallated 1-(E)-pentadecenylzirconocene chloride with (S)-1 [46,47]. When the reaction was performed in THF at 0 °C and 50 mol % of ZnBr2 was added, the reaction gave the anti-adduct 49 as the major diastereomer (12:1 anti/syn). When the amount of ZnBr2 was lowered to half (25 mol %) the selectivity rose to 20:1 (anti/syn). The selectivity was reversed to 1:15 (anti/syn) favouring the syn-adduct 16, when the solvent was changed to less coordinating CH2Cl2 and the 1-(E)-pentadecenylzirconocene chloride was transmetallated with Et2Zn prior to the addition of (S)-1. Interestingly, when the addition was performed in THF in the presence of the transmetallated 1-(E)-pentadecenyl(ethyl)zinc, the selectivity was inverted, and the anti-adduct 49 was favoured (12:1 anti/syn).

Scheme 21: (a) Cp2Zr(H)Cl, cat. AgAsF6, CH2Cl2, rt; (b) Cp2Zr(H)Cl, 1-pentadecyne, cat. ZnBr2 in THF for anti-selective or ZnEt2 in CH2Cl2 for syn-selective reaction. (c) Cp2Zr(H)Cl, Et2Zn, in CH2Cl2, for syn-selective reaction or in THF for anti-selective reaction.

Scheme 21: (a) Cp2Zr(H)Cl, cat. AgAsF6, CH2Cl2, rt; (b) Cp2Zr(H)Cl, 1-pentadecyne, cat. ZnBr2 in THF for anti-...

We have also been interested in the use of hydrozirconation–transmetallation process while working on the synthesis of galactonojirimycin (Scheme 21) [48]. We used the TBS-protected propargyl alcohol 31 as the nucleophile, which had been investigated by Negishi for the hydrozirconation–transmetallation process [80]. Our findings were in agreement with the results of Murakami. High syn-selectivity (>1:20 anti/syn) was achieved in CH2Cl2 with Et2Zn as the transmetallating agent. The reaction could also be performed in toluene, but the hydrozirconation had to be done in CH2Cl2 due to the low solubility of the Schwartz’s reagent in toluene. After formation of the hydrozirconated species, the solvent could be changed to toluene. This reaction gave a slightly lower yield in toluene, but identical selectivity favouring adduct 60. By changing the solvent to THF the stereochemical outcome was reversed. The anti-adduct 59 could be isolated in a >20:1 anti/syn ratio. Unfortunately, the chemical yield was substantially lower (20%) and many byproducts were observed. Most importantly, these reaction conditions did not affect the chiral integrity of (S)-1. In a recent synthesis of (−)-1-deoxyaltronojirimycin we tried to synthesize the anti-adduct 59 [43]. Poor yield for vinylic addition forced us to look for alternative methods (Scheme 22). Despite the literature precedence of anti-selective reactions, we were unable to selectively synthesize this adduct in a good yield. We then turned to the lithiated nucleophile 31. In THF at −78 °C high diastereoselectivity (15:1 anti/syn) was obtained. Unfortunately, direct reduction of 32 to 59 produced allene as a byproduct, which forced us to modify the synthetic route.

Scheme 22: (a) i) 31, n-BuLi, THF, −78 °C; ii) (S)-1, THF, −78 °C; (b) Red-Al, THF, 0 °C.

Scheme 22: (a) i) 31, n-BuLi, THF, −78 °C; ii) (S)-1, THF, −78 °C; (b) Red-Al, THF, 0 °C.

We have also successfully used (Z)-vinyl nucleophiles created from the vinyl iodide 61 in the stereoselective synthesis of pachastrissamine (11) [81,82] and norfuranomycin [37] (Scheme 23). After halogen–metal exchange with n-BuLi, the newly formed nucleophile reacts with (S)-1. When HMPT or dimethylpropyleneurea (DMPU) were used, high anti-selectivities were achieved (up to 17:1 anti/syn). Without additives the reaction gave a 4:1 anti/syn mixture of allylic alcohols 62 and 63. Chelating metals gave rise to the syn-adduct 63. When we used ZnCl2 dissolved in Et2O as the chelating agent, the syn-selectivity rose to about 1:6 favouring adduct 63. These results are in agreement with the findings of Jurczak [68].

Scheme 23: (a) 61, n-BuLi, DMPU, toluene, −78 °C, then (S)-1, toluene, −95 °C (57%); (b) 61, n-BuLi, ZnCl2, toluene, −78 °C, then (S)-1, toluene, −95 °C (72%).

Scheme 23: (a) 61, n-BuLi, DMPU, toluene, −78 °C, then (S)-1, toluene, −95 °C (57%); (b) 61, n-BuLi, ZnCl2, to...

The alkylation results are summarized in Table 1, and overall one can conclude that Garner’s aldehyde 1 is a highly versatile intermediate for organic synthesis. The selectivity of the 1,2-asymmetric induction can be controlled, either by choice of the nucleophilic reagent, chelating or aggregates breaking additives, solvent and sometimes also by the reaction temperature. Less coordinating metals and more reactive nucleophiles tend to give Felkin–Anh products (Table 1, entries 2, 5, 6, 12–14, 16, 18, 19 and 28). Smaller alkyne nucleophiles seem to give a roughly 8:1 anti/syn-selectivity. The larger organovinyl reagents give slightly lower anti-selectivities of about 3:1 to 5:1. Highest selectivities are reached with transition metals, such as Rh and Ni (Table 1, entries 12, 18 and 19). The anti-selectivity can be enhanced either by the addition of aggregation breaking additives, such as HMPT and DMPU (Table 1, entries 1, 4, 10 and 27) or by the use of strongly Lewis basic solvents, like THF (Table 1, entries 2, 5, 13, 14, 16 and 24). Using aggregate breaking additives increases the anti-selectivities from 4–5:1 to >20:1. The increase of nucleophilicity diminishes the metal cations capability or chances to coordinate to the carbonyl groups. This promotes the attack of the nucleophile from the least hindered re side.

Table 1: Selectivities and yield for additions of various nucleophiles to Garner’s aldehyde 1.

| Entry | Nucleophile | Additive | Solvent | T (°C) | anti/syn | Yield (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

HMPT | THF | −78 | >20:1 | 71 | [59] |

| 2 |

|

– | THF | −23 | 8:1 | 83 | [50] |

| 3 |

|

ZnBr2 | Et2O | −78 → rt | 1:15 | 87 | [59] |

| 4 |

|

HMPT | toluene | −78 → 0 | 20:1 | 85 | [58] |

| 5 |

|

– | THF | −78 | 15:1 | 80 | [43] |

| 6 |

|

– | toluene | −78 → rt | 3:1 | 80 | [58] |

| 7 |

|

ZnCl2 | toluene/Et2O | −78 → rt | 1:10 | 65 | [58] |

| 8 |

|

CuI | THF/Me2S | −78 | 1:16 | 95 | [72] |

| 9 |

|

ZnBr2 | THF/toluene | −78 | 1:1 | – | [73] |

| 10 |

|

HMPT | THF | −78 | 13:1 | 75 | [38] |

| 11 |

|

– | Et2O | −78 → 0 | 1:12 | 62 | [74] |

| 12 |

|

– | THF | 40 | 20:1 | 74 | [71] |

| 13 |

|

– | THF | −78 | 5:1 | – | [61] |

| 14 |

|

– | THF | −78 | 3:1 | – | [61] |

| 15 |

|

– | Et2O | −78 → rt | 1:6 | 85 | [61] |

| 16 |

|

– | THF | −78 → 0 | 5:1 | – | [62] |

| 17 |

|

– | Et2O | 0 | 2:3 | – | [63] |

| 18 |

|

– | aq DME | 55 | 4.6:1 | 78 | [65] |

| 19 |

|

– | THF | rt | >20:1 | 78 | [76] |

| 20 |

|

– | THF | −78 | 1:2 | >80 | [50] |

| 21 |

|

AgAsF6 | CH2Cl2 | rt | 1:1 | 70 | [78] |

| 22 |

|

ZnBr2 | THF | 0 → rt | 20:1 | 70 | [46] |

| 23 |

|

Et2Zn | CH2Cl2 | −30 → 0 | 1:15 | 84 | [46] |

| 24 |

|

Et2Zn | THF | −20 → rt | 12:1 | 67 | [46] |

| 25 |

|

Et2Zn | CH2Cl2 | −40 → 0 | >1:20 | 78 | [48] |

| 26 |

|

Et2Zn | THF | −40 → 0 | >20:1 | 20 | [48] |

| 27 |

|

DMPU | toluene | −95 | 17:1 | 57 | [81,82] |

| 28 |

|

– | toluene | −95 | 4:1 | 63 | [81,82] |

| 29 |

|

ZnCl2 | toluene/Et2O | −95 | 1:6 | 72 | [81,82] |

| 30 |

|

CuI (cat.)

BF3·Et2O |

THF | −50 | >99:1 | 70 | [66] |

Chelation control can also be achieved by the proper choice of solvents. Even changing from THF to Et2O is often enough to inverse the selectivity (Table 1, entries 10, 11, 16 and 17). Less coordinating solvents, such as toluene or CH2Cl2 can also affect the selectivity. A greater effect on the selectivity can be reached by the addition of Lewis acids. Usually Zn(II)-salts give fair to good syn-selectivities (Table 1, entries 3, 7, 23, 25 and 29), if the solvent is non-coordinating (Et2O, toluene or CH2Cl2). Zn(II)-salts do not necessarily give syn-selectivities, especially if they are too reactive to chelate to the substrate (Table 1, entry 9). Vinylalanes give varying results, preferring either anti- or syn-selectivity (Table 1, entry 20).

Olefination of Garner’s aldehyde

Olefination of 1 provides an easy access to chiral 2-aminohomoallylic alcohols A (Scheme 24). The intermediate can be derivatized further, thus providing a route for greater molecular diversity. Diastereoselective dihydroxylation of A with OsO4 leads to triols B, which have been utilized in the syntheses of calyculins family [83,84], D-ribo-phytosphingosine [85], and radicamine [86,87]. If the R-group in A is an ester, diastereoselective Michael addition leads to structures C [88-92]. Kainic acid was synthesized using such conjugate addition [93], and a recent synthesis of lucentamycin A was achieved using this strategy [94]. Epoxidation of A leads to a highly functional intermediate C, which has been used in the synthesis of manzacidin B [95].

Scheme 24: Olefin A as an intermediate in natural product synthesis.

Scheme 24: Olefin A as an intermediate in natural product synthesis.

Among the plethora of olefination reactions, the Wittig [96,97] and Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons [98-100] reactions are most commonly used for the introduction of a double bond to Garner’s aldehyde 1. Two things need to be considered before performing the olefination reactions: 1) epimerization of the stereocenter in the aldehyde (i.e. basicity vs nucleophilicity of the olefinating reagents) and 2) E/Z-selectivity of the reaction.

Moriwake et al. noticed in their synthesis of vinylglycinol 64 that the reaction of methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide with KH as the base provided 62 in fairly good yield, but with complete racemization of the product (Scheme 25) [101]. This racemization could be overcome by performing the olefination with AlMe3–Zn–CH2I2 in benzene under non-basic conditions. While looking for non-racemizing conditions for the same reaction, Beaulieu et al. found that the ylide formed from methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide and n-BuLi in THF gave 62 in 69% ee, but in low yield (27%) [102]. With a different unstabilized ylide 65, the enantiopurity of the Wittig product increased to >95% ee. The erosion of enantiopurity was attributed to the ylide (Ph3P=CH2) being too basic. It is well known that phosphonium ylides form stable complexes with alkali metals during the dehydrohalogenation of the phosphonium salt [103]. These complexes react with carbonyl compounds differently. Addition reactions of other ylides to 1, proceeded with little or no racemization of 1. The E/Z-ratio of the reaction was 1:13 favouring the Z-adduct 66. In comparison to Beaulieu’s results, McKillop [27] noticed that with KHMDS as the base, there was no epimerization at all! To prepare “salt-free” ylides, it is necessary to remove lithium halide from the reaction solution. On the other hand KHMDS is a convenient base for the preparation of “salt-free” ylides.

Scheme 25: (a) Ph3(Me)PBr, KH, benzene (66%, rac-64) or (b) AlMe3, Zn, CH2I2, THF (76%) [101]; (c) Ph3(Me)PBr, n-BuLi, THF, −75 °C, then (S)-1 (27%, 69% ee) [102]; (d) 65, n-BuLi, THF, −75 °C, then (S)-1 (78%, 1:13 E/Z, >95% ee); (e) 67, KHMDS, THF, −78 °C, then (S)-1, quenching with MeOH (70%, >10:1 E/Z) [104].

Scheme 25: (a) Ph3(Me)PBr, KH, benzene (66%, rac-64) or (b) AlMe3, Zn, CH2I2, THF (76%) [101]; (c) Ph3(Me)PBr, n-Bu...

High Z-selectivity is a typical outcome with unstabilized ylides. Kim has investigated means of reversing the E/Z-selectivity to favour the E-isomer [104]. They noticed that olefination under the usual Wittig conditions provided high Z-selectivity (1:15 E/Z). When the reaction was quenched with MeOH at −78 °C, the E/Z-ratio was reversed to >10:1 favouring adduct 68 [105].

α,β-Unsaturated esters can be synthesized from stabilized ylides. Reaction of 1 with ylide 69 is E-selective. Depending on the solvent, the E/Z-ratio can vary from 3:1 (in MeOH) [106] to 100:0 (THF [107] or benzene [108]). Since stabilized ylides are less reactive compared to their non-stabilized counterparts, they tend to epimerize the existing chiral center of 1 a lot less, if at all (pKaH value of 69 in DMSO is 8.5 compared to the pKa value of Ph3(Me)PBr, which is 22.5) [109]. Another method to prepare α,β-unsaturated esters is the Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction (HWE). The HWE reaction has many advantages over the Wittig olefination. The phosphonate anions tend to be more nucleophilic (less basic) than the corresponding phosphorous ylides. The byproducts, dialkyl phosphates are water soluble and hence easier to remove from the product compared to, e.g., triphenylphospine oxide. As with the Wittig reaction, the HWE reaction can also promote the epimerization of the α-proton (pKa of triethoxyphosphonoacetate in DMSO is 18.6) [109]. We have experienced this tendency especially with α-amino ketophosphonates [110], but there is also evidence that aldehyde 1 can lose some of its chiral integrity in the HWE reaction. For base sensitive substrates the use of metal salts (LiCl or NaI) and an amine base (DBU or DIPEA) has proven to be effective in avoiding epimerization [111]. The use of Ba(OH)2 in aq THF has also been advocated to prevent epimerization [112], and recently Myers has reported the superiority of lithium hexafluoroisopropoxide as a mild base for HWE olefinations of epimerizable aldehydes [113]. Jako et al. showed that E-enoate 72 can be synthesized from Garner’s aldehyde (R)-1 in 95:5 E/Z-selectivity and practically with no degradation of chiral integrity (Scheme 26) [89]. As an alternative, Lebel and Ladjel used a catalytic amount of [Ir(COD)Cl]2 for the in situ preparation of ylide 69 [114]. They obtained a 81% yield in the reaction.

Scheme 26: (a) Benzene, rt (82%) [108]; (b) K2CO3, MeOH (85%) [89]; (c) iPrOH, [Ir(COD)Cl]2, PPh3, THF, rt (81%) [114].

Scheme 26: (a) Benzene, rt (82%) [108]; (b) K2CO3, MeOH (85%) [89]; (c) iPrOH, [Ir(COD)Cl]2, PPh3, THF, rt (81%) [114].

We have been interested in the synthesis of Z-enoate 73 [84]. The Still–Gennari modification to the phosphonate makes the synthesis of Z-enoates possible [115]. The two electron-withdrawing CF3CH2O-groups destabilize the cis-oxaphosphetane intermediate (Scheme 27) and make the elimination reaction to the kinetic product Z-alkene a lot faster. As the elimination step becomes fast, the rate difference in the initial addition step between kanti and ksyn determines the overall Z-selectivity. When the reaction was performed with K2CO3/18-crown-6 as the base in toluene at −15 °C, we could isolate only the Z-enoate 73 in good yield (90%). HPLC analysis showed that there was no epimerization.

Scheme 27: Mechanism of the Still–Gennari modification of the HWE reaction leading to both olefin isomers.

Scheme 27: Mechanism of the Still–Gennari modification of the HWE reaction leading to both olefin isomers.

We have recently shown that the open-chain aldehyde 74 reacts with the Still–Gennari phosphonate and provides the Z-enoate 75 in good E/Z-selectivity (1:12) [84]. The slight decrease in the E/Z-selectivity can be reasoned with the smaller size of the aldehyde 74. When the aldehyde is coordinating to the phosphonate, the steric hindrance caused by the interaction of the trifluoroethoxy group with the aldehyde R’ in TS (syn) is smaller compared with aldehyde 1. This allows some of the aldehyde to react via the trans-oxaphosphetane intermediate. Using these reaction conditions no epimerization was observed.

Conclusion

Garner’s aldehyde has developed into a useful and reliable synthetic intermediate for the synthesis of enantiopure complex natural products, their analogues and other pharmacologically active compounds. Several reaction types have been studied sufficiently so that one has reliable tools to plan a synthesis. Simple addition reactions to the carbonyl group give access to vicinal amino alcohols, important building blocks for many natural products. Another possibility for carbon chain elongation are olefination reactions, which often lead to epimerization of the α-stereocenter. As with the alkylations, strategies to avoid this undesired reaction have been developed. However, despite these important achievements, much more research needs to be done to increase the scopes of these reactions, the overall efficiency, and environmental sustainability.

References

-

Vallery-Radot, R.; Devonshire, R. L. Life of Pasteur (transl.); Dover Publications: New York, 1960; p 484.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ramos Tombo, G. M.; Belluš, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 1193–1215. doi:10.1002/anie.199111933

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lamberth, C. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 7239–7256. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.06.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vaenkatesan, V.; Wegh, R. T.; Teunissen, J.-P.; Lub, J.; Bastiaansen, C. W. M.; Broer, D. J. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2005, 15, 138–142. doi:10.1002/adfm.200400122

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhuang, X. X.; Sun, X. X.; Li, L.; Li, Y. C. Adv. Mat. Res. 2011, 337, 151–154. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.337.151

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Armstrong, R. W.; Beau, J. M.; Cheon, S. H.; Christ, W. J.; Fujioka, H.; Ham, W. H.; Hawkins, L. D.; Jin, H.; Kang, S. H.; Kishi, Y.; Martinelli, M. J.; McWhorter, W. W., Jr.; Mizuno, M.; Nakata, M.; Stutz, A. E.; Talamas, F. X.; Taniguchi, M.; Tino, J. A.; Ueda, K.; Uenishi, J.; White, J. B.; Yonaga, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7525–7530. doi:10.1021/ja00201a037

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Armstrong, R. W.; Beau, J. M.; Cheon, S. H.; Christ, W. J.; Fujioka, H.; Ham, W. H.; Hawkins, L. D.; Jin, H.; Kang, S. H.; Kishi, Y.; Martinelli, M. J.; McWhorter, W. W., Jr.; Mizuno, M.; Nakata, M.; Stutz, A. E.; Talamas, F. X.; Taniguchi, M.; Tino, J. A.; Ueda, K.; Uenishi, J.; White, J. B.; Yonaga, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7530–7533. doi:10.1021/ja00201a038

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suh, E. M.; Kishi, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 11205–11206. doi:10.1021/ja00103a065

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mangeney, P.; Andriamialisoa, R. Z.; Langlois, N.; Langlois, Y.; Potier, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 2243–2245. doi:10.1021/ja00502a072

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kutney, J. P.; Choi, L. S. L.; Nakano, J.; Tsukamoto, H.; McHugh, M.; Boulet, C. A. Heterocycles 1988, 27, 1845–1853. doi:10.3987/COM-88-4611

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuehne, M. E.; Matson, P. A.; Bornmann, W. G. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 513–528. doi:10.1021/jo00002a008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Magnus, P.; Mendoza, J. S.; Stamford, A.; Ladlow, M.; Willis, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10232–10245. doi:10.1021/ja00052a020

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yokoshima, S.; Ueda, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, A.; Kuboyama, T.; Tokuyama, H.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2137–2139. doi:10.1021/ja0177049

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ishikawa, H.; Colby, D. A.; Seto, S.; Va, P.; Tam, A.; Kakei, H.; Rayl, T. J.; Hwang, I.; Boger, D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4904–4916. doi:10.1021/ja809842b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nicolaou, K. C.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J. J.; Ueno, H.; Nantermet, P. G.; Guy, R. K.; Claiborne, C. F.; Renaud, J.; Couladouros, E. A.; Paulvannan, K.; Sorensen, E. J. Nature 1994, 367, 630–634. doi:10.1038/367630a0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Holton, R. A.; Somoza, C.; Kim, H. B.; Liang, F.; Biediger, R. J.; Boatman, P. D.; Shindo, M.; Smith, C. C.; Kim, S.; Nadizadeh, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Tao, C.; Vu, P.; Tang, S.; Zhang, P.; Murthi, K. K.; Gentile, L. N.; Liu, J. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 1597–1598. doi:10.1021/ja00083a066

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Holton, R. A.; Somoza, C.; Kim, H. B.; Liang, F.; Biediger, R. J.; Boatman, P. D.; Shindo, M.; Smith, C. C.; Kim, S.; Nadizadeh, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Tao, C.; Vu, P.; Tang, S.; Zhang, P.; Murthi, K. K.; Gentile, L. N.; Liu, J. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 1599–1600. doi:10.1021/ja00083a067

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Danishefsky, S. J.; Masters, J. J.; Young, W. B.; Link, J. T.; Snyder, L. B.; Magee, T. V.; Jung, D. K.; Isaacs, R. C. A.; Bornmann, W. G.; Alaimo, C. A.; Coburn, C. A.; Di Grandi, M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 2843–2859. doi:10.1021/ja952692a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wender, P. A.; Badham, N. F.; Conway, S. P.; Floreancig, P. E.; Glass, T. E.; Gränicher, C.; Houze, J. B.; Jaenichen, J.; Lee, D.; Marquess, D. G.; McGrane, P. L.; Meng, W.; Mucciaro, T. P.; Mühlebach, M.; Natchus, M. G.; Paulsen, H.; Rawlins, D. B.; Satkofsky, J.; Shuker, A. J.; Sutton, J. C.; Taylor, R. E.; Tomooka, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2755–2756. doi:10.1021/ja9635387

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wender, P. A.; Badham, N. F.; Conway, S. P.; Floreancig, P. E.; Glass, T. E.; Houze, J. B.; Krauss, N. E.; Lee, D.; Marquess, D. G.; McGrane, P. L.; Meng, W.; Natchus, M. G.; Shuker, A. J.; Sutton, J. C.; Taylor, R. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2757–2758. doi:10.1021/ja963539z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morihira, K.; Hara, R.; Kawahara, S.; Nishimori, T.; Nakamura, N.; Kusama, H.; Kuwajima, I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 12980–12981. doi:10.1021/ja9824932

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mukaiyama, T.; Shiina, I.; Iwadare, H.; Saitoh, M.; Nishimura, T.; Ohkawa, N.; Sakoh, H.; Nishimura, K.; Tani, Y.-I.; Hasegawa, M.; Yamada, K.; Saitoh, K. Chem.–Eur. J. 1999, 5, 121–161. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3765(19990104)5:1<121::AID-CHEM121>3.3.CO;2-F

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Doi, T.; Fuse, S.; Miyamoto, S.; Nakai, K.; Sasuga, D.; Takahashi, T. Chem.–Asian J. 2006, 1, 370–383. doi:10.1002/asia.200600156

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Garner, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 5855–5858. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)81703-2

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Garner, P.; Park, J. M. Org. Synth. 1990, 70, 18–28.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Garner, P.; Park, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 2361–2364. doi:10.1021/jo00388a004

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

McKillop, A.; Taylor, R. J. K.; Watson, R. J.; Lewis, N. Synthesis 1994, 31–33. doi:10.1055/s-1994-25398

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Dondoni, A.; Perroni, D. Org. Synth. 2000, 77, 64–77.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Roush, W. R.; Hunt, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 798–806. doi:10.1021/jo00109a008

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ocejo, M.; Vicario, J. L.; Badía, D.; Carrillo, L.; Reyes, E. Synlett 2005, 2110–2112. doi:10.1055/s-2005-871947

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jurczak, J.; Gryko, D.; Kobrzycka, E.; Gruza, H.; Prokopowicz, P. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 6051–6064. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00299-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rauhala, V. Master’s thesis, Department of Chemistry, University of Oulu, 1998, p. 87.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Clemens, A. J. L.; Burke, S. D. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 2983–2985. doi:10.1021/jo300025t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huntley, R. J.; Funk, R. L. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4775–4778. doi:10.1021/ol0617547

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chattopadhyay, S. K.; Sarkar, K.; Karmakar, S. Synlett 2005, 2083–2085. doi:10.1055/s-2005-871944

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bandyopadhyay, A.; Pal, B. K.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 1875–1877. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.07.032

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 6736–6738. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.10.007

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Garner, P.; Park, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 3772–3787. doi:10.1021/jo00299a017

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Takahata, H.; Banba, Y.; Ouchi, H.; Nemoto, H. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 2527–2529. doi:10.1021/ol034886y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takahata, H.; Banba, Y.; Sasatani, M.; Nemoto, H.; Kato, A.; Adachi, I. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 8199–8205. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.06.112

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guaragna, A.; D’Errico, S.; D’Alonzo, D.; Pedatella, S.; Palumbo, G. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3473–3476. doi:10.1021/ol7014847

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guaragna, A.; D’Alonzo, D.; Paolella, C.; Palumbo, G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 2045–2047. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.111

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karjalainen, O. K.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1231–1236. doi:10.1039/c0ob00747a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Garner, P.; Park, J. M.; Malecki, E. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 4395–4398. doi:10.1021/jo00253a039

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Soai, K.; Takahashi, K. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1994, 1257–1258. doi:10.1039/P19940001257

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Murakami, T.; Furusawa, K. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 9257–9263. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01190-0

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Murakami, T.; Furusawa, K.; Tamai, T.; Yoshikai, K.; Nishikawa, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 1115–1119. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.010

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Karjalainen, O. K.; Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1145–1147. doi:10.1021/ol100037c

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Tamborini, L.; Conti, P.; Pinto, A.; Colleoni, S.; Gobbi, M.; De Micheli, C. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6083–6089. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.05.054

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lemke, A.; Büschleb, M.; Ducho, C. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 208–214. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.10.102

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Chisholm, J. D.; Van Vranken, D. L. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 7541–7553. doi:10.1021/jo000911r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liang, X.; Andersch, J.; Bols, M. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 2136–2157. doi:10.1039/B101054I

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karjalainen, O. K.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 4311–4326. doi:10.1039/c2ob25357g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reginato, G.; Meffre, P.; Gaggini, F. Amino Acids 2005, 29, 81–87. doi:10.1007/s00726-005-0184-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ahn, N. T. Top. Curr. Chem. 1980, 88, 146–162.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cram, D. J.; Abd Elhafez, F. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 5828–5835. doi:10.1021/ja01143a007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reetz, M. T.; Hüllmann, M.; Seitz, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1987, 26, 477–480. doi:10.1002/anie.198704771

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gruza, H.; Kiciak, K.; Krasiński, A.; Jurczak, J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 2627–2631. doi:10.1016/S0957-4166(97)00306-6

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Herold, P. Helv. Chim. Acta 1988, 71, 354–362. doi:10.1002/hlca.19880710208

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Dale, J. A.; Dull, D. L.; Mosher, H. S. J. Org. Chem. 1969, 34, 2543–2549. doi:10.1021/jo01261a013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Coleman, R. S.; Carpenter, A. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 1697–1700. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)91709-X

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Williams, L.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, F.; Carroll, P. J.; Joullié, M. M. Tetrahedron 1995, 52, 11673–11694. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(96)00672-2

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Koskinen, A. M. P.; Hassila, H.; Myllymäki, V. T.; Rissanen, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 5619–5622. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)01029-H

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Marcus, Y. The Properties of Solvents; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 1998; pp 142–160.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fürstner, A.; Krause, H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2001, 343, 343–350. doi:10.1002/1615-4169(20010430)343:4<343::AID-ADSC343>3.3.CO;2-Q

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Shimizu, M.; Wakioka, I.; Fujisawa, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 6027–6030. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01340-3

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wong, L.; Tan, S. S. L.; Lam, Y.; Melendez, A. J. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 3618–3626. doi:10.1021/jm900121d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mori, K.; Masuda, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 9197–9200. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.10.025

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chun, J.; Byun, H.-S.; Bittman, R. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 348–354. doi:10.1021/jo026240+

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yadav, J. S.; Geetha, V.; Krishnam Raju, A.; Gnaneshwar, D.; Chandrasekhar, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 2983–2985. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(03)00390-3

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Dhondi, P. K.; Carberry, P.; Choi, L. B.; Chisholm, J. D. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9590–9596. doi:10.1021/jo701643h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Zhang, X.; van der Donk, W. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2212–2213. doi:10.1021/ja067672v

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Reginato, G.; Mordini, A.; Tenti, A.; Valacchi, M.; Broguiere, J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 2882–2886. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.12.025

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hanessian, S.; Yang, G.; Rondeau, J.-M.; Neumann, U.; Betschart, C.; Tinelnot-Blomley, M. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 4544–4567. doi:10.1021/jm060154a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Soai, K.; Ookawa, A.; Kaba, T.; Ogawa, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 7111–7115. doi:10.1021/ja00257a034

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sa-ei, K.; Montgomery, J. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6707–6711. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.05.029

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Suzuki, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Imai, T.; Maeta, H.; Ohba, S. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 4483–4494. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(94)01135-M

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wipf, P.; Xu, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 5197–5200. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77062-6

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wipf, P.; Jahn, H. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 12853–12910. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(96)00754-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, C.; Negishi, E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 431–434. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)02394-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 980–983. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.12.014

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1774–1783. doi:10.1039/c0ob00643b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Koskinen, A. M. P.; Chen, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 6977–6980. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(91)80459-J

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Synthesis 2010, 2816–2822. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1218843

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Jeon, J.; Shin, M.; Yoo, J. W.; Oh, J. S.; Bae, J. G.; Jung, S. H.; Kim, Y. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 1105–1108. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.12.084

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ribes, C.; Falomir, E.; Carda, M.; Marco, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7779–7782. doi:10.1021/jo8012989

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mallesham, P.; Vijaykumar, B. V. D.; Shin, D.-S.; Chandrasekhar, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 6145–6147. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.09.034

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jako, I.; Uiber, P.; Mann, A.; Taddei, M.; Wermuth, C. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 1011–1014. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94416-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoda, H.; Shirai, T.; Katagiri, T.; Takabe, K.; Kimata, K.; Hosoya, K. Chem. Lett. 1990, 2037–2038. doi:10.1246/cl.1990.2037

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hanessian, S.; Sumi, K. Synthesis 1991, 1083–1089. doi:10.1055/s-1991-28396

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hanessian, S.; Demont, E.; van Otterlo, W. A. L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 4999–5003. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)00765-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rastogi, S. K.; Kornienko, A. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2006, 17, 3170–3178. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2006.11.029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jako, I.; Uiber, P.; Mann, A.; Wermuth, C.-G. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 5729–5733. doi:10.1021/jo00019a055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ranatunga, S.; Tang, C.-H. A.; Hu, C.-C. A.; Del Valle, J. R. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9859–9864. doi:10.1021/jo301723y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sankar, K.; Rahman, H.; Das, P. P.; Bhimireddy, E.; Sridhar, B.; Mohapatra, D. K. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1082–1085. doi:10.1021/ol203466m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wittig, G.; Schöllkopf, U. Chem. Ber. 1954, 87, 1318–1330. doi:10.1002/cber.19540870919

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wittig, G.; Haag, W. Chem. Ber. 1955, 88, 1654–1666. doi:10.1002/cber.19550881110

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Horner, L.; Hoffmann, H.; Wippel, H. G. Chem. Ber. 1958, 91, 61–63. doi:10.1002/cber.19580910113

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Horner, L.; Hoffmann, H.; Wippel, H. G.; Klahre, G. Chem. Ber. 1959, 92, 2499–2505. doi:10.1002/cber.19590921017

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wadsworth, W. S., Jr.; Emmons, W. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 1733–1738. doi:10.1021/ja01468a042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moriwake, T.; Hamano, S.; Saito, S.; Torii, S. Chem. Lett. 1987, 2085–2088. doi:10.1246/cl.1987.2085

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Beaulieu, P. L.; Duceppe, J.-S.; Johnson, C. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4196–4204. doi:10.1021/jo00013a023

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kolodiazhnyi, O. I. Phosphorus ylides – Chemistry and Application in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1999; pp 9–156. doi:10.1002/9783527613908.ch02

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oh, J. S.; Kim, B. H.; Kim, Y. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 3925–3928. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.03.101

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Schlosser, M.; Christmann, K. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1966, 5, 126. doi:10.1002/anie.196601261

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Drew, M. G. B.; Harrison, R. J.; Mann, J.; Tench, A. J.; Young, R. J. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 1163–1172. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)01094-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Upadhyay, P. K.; Kumar, P. Synthesis 2010, 3063–3066. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258185

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dondoni, A.; Merino, P.; Perrone, D. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 2939–2956. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)80389-6

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bordwell, F. G. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988, 21, 456–463. doi:10.1021/ar00156a004

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Pelšs, A.; Kumpulainen, E. T. T.; Koskinen, A. M. P. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 7598–7601. doi:10.1021/jo9017588

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blanchette, M. A.; Choy, W.; Davis, J. T.; Essenfeld, A. P.; Masamune, S.; Roush, W. R.; Sakai, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 2183–2186. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80205-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paterson, I.; Yeung, K.-S.; Smaill, J. B. Synlett 1993, 774–776. doi:10.1055/s-1993-22605

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blasdel, L. K.; Myers, A. G. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 4281–4283. doi:10.1021/ol051785m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lebel, H.; Ladjel, C. Organometallics 2008, 27, 2676–2678. doi:10.1021/om800255c

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Still, W. C.; Gennari, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 4405–4408. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)85909-2

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 48. | Karjalainen, O. K.; Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1145–1147. doi:10.1021/ol100037c |

| 80. | Xu, C.; Negishi, E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 431–434. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)02394-6 |

| 78. | Wipf, P.; Xu, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 5197–5200. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77062-6 |

| 79. | Wipf, P.; Jahn, H. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 12853–12910. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(96)00754-5 |

| 46. | Murakami, T.; Furusawa, K. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 9257–9263. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01190-0 |

| 47. | Murakami, T.; Furusawa, K.; Tamai, T.; Yoshikai, K.; Nishikawa, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 1115–1119. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.010 |

| 77. | Suzuki, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Imai, T.; Maeta, H.; Ohba, S. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 4483–4494. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(94)01135-M |

| 37. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 6736–6738. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.10.007 |

| 68. | Mori, K.; Masuda, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 9197–9200. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.10.025 |

| 43. | Karjalainen, O. K.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1231–1236. doi:10.1039/c0ob00747a |

| 81. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 980–983. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.12.014 |

| 82. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1774–1783. doi:10.1039/c0ob00643b |

| 58. | Gruza, H.; Kiciak, K.; Krasiński, A.; Jurczak, J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 2627–2631. doi:10.1016/S0957-4166(97)00306-6 |

| 81. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 980–983. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.12.014 |

| 82. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1774–1783. doi:10.1039/c0ob00643b |

| 58. | Gruza, H.; Kiciak, K.; Krasiński, A.; Jurczak, J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 2627–2631. doi:10.1016/S0957-4166(97)00306-6 |

| 81. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 980–983. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.12.014 |

| 82. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1774–1783. doi:10.1039/c0ob00643b |

| 58. | Gruza, H.; Kiciak, K.; Krasiński, A.; Jurczak, J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 2627–2631. doi:10.1016/S0957-4166(97)00306-6 |

| 66. | Shimizu, M.; Wakioka, I.; Fujisawa, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 6027–6030. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01340-3 |

| 43. | Karjalainen, O. K.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1231–1236. doi:10.1039/c0ob00747a |

| 81. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 980–983. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.12.014 |

| 82. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1774–1783. doi:10.1039/c0ob00643b |

| 50. | Lemke, A.; Büschleb, M.; Ducho, C. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 208–214. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.10.102 |

| 46. | Murakami, T.; Furusawa, K. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 9257–9263. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01190-0 |

| 46. | Murakami, T.; Furusawa, K. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 9257–9263. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01190-0 |

| 48. | Karjalainen, O. K.; Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1145–1147. doi:10.1021/ol100037c |

| 48. | Karjalainen, O. K.; Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1145–1147. doi:10.1021/ol100037c |

| 46. | Murakami, T.; Furusawa, K. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 9257–9263. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01190-0 |

| 38. | Garner, P.; Park, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 3772–3787. doi:10.1021/jo00299a017 |

| 74. | Hanessian, S.; Yang, G.; Rondeau, J.-M.; Neumann, U.; Betschart, C.; Tinelnot-Blomley, M. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 4544–4567. doi:10.1021/jm060154a |

| 72. | Zhang, X.; van der Donk, W. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2212–2213. doi:10.1021/ja067672v |

| 73. | Reginato, G.; Mordini, A.; Tenti, A.; Valacchi, M.; Broguiere, J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 2882–2886. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.12.025 |

| 83. | Koskinen, A. M. P.; Chen, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 6977–6980. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(91)80459-J |

| 84. | Passiniemi, M.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Synthesis 2010, 2816–2822. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1218843 |

| 98. | Horner, L.; Hoffmann, H.; Wippel, H. G. Chem. Ber. 1958, 91, 61–63. doi:10.1002/cber.19580910113 |

| 99. | Horner, L.; Hoffmann, H.; Wippel, H. G.; Klahre, G. Chem. Ber. 1959, 92, 2499–2505. doi:10.1002/cber.19590921017 |

| 100. | Wadsworth, W. S., Jr.; Emmons, W. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 1733–1738. doi:10.1021/ja01468a042 |

| 68. | Mori, K.; Masuda, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 9197–9200. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.10.025 |

| 96. | Wittig, G.; Schöllkopf, U. Chem. Ber. 1954, 87, 1318–1330. doi:10.1002/cber.19540870919 |

| 97. | Wittig, G.; Haag, W. Chem. Ber. 1955, 88, 1654–1666. doi:10.1002/cber.19550881110 |

| 102. | Beaulieu, P. L.; Duceppe, J.-S.; Johnson, C. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4196–4204. doi:10.1021/jo00013a023 |

| 58. | Gruza, H.; Kiciak, K.; Krasiński, A.; Jurczak, J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 2627–2631. doi:10.1016/S0957-4166(97)00306-6 |

| 101. | Moriwake, T.; Hamano, S.; Saito, S.; Torii, S. Chem. Lett. 1987, 2085–2088. doi:10.1246/cl.1987.2085 |

| 1. | Vallery-Radot, R.; Devonshire, R. L. Life of Pasteur (transl.); Dover Publications: New York, 1960; p 484. |

| 93. | Jako, I.; Uiber, P.; Mann, A.; Wermuth, C.-G. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 5729–5733. doi:10.1021/jo00019a055 |

| 88. | Jako, I.; Uiber, P.; Mann, A.; Taddei, M.; Wermuth, C. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 1011–1014. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94416-2 |

| 89. | Yoda, H.; Shirai, T.; Katagiri, T.; Takabe, K.; Kimata, K.; Hosoya, K. Chem. Lett. 1990, 2037–2038. doi:10.1246/cl.1990.2037 |

| 90. | Hanessian, S.; Sumi, K. Synthesis 1991, 1083–1089. doi:10.1055/s-1991-28396 |

| 91. | Hanessian, S.; Demont, E.; van Otterlo, W. A. L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 4999–5003. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)00765-6 |

| 92. | Rastogi, S. K.; Kornienko, A. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2006, 17, 3170–3178. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2006.11.029 |

| 95. | Sankar, K.; Rahman, H.; Das, P. P.; Bhimireddy, E.; Sridhar, B.; Mohapatra, D. K. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1082–1085. doi:10.1021/ol203466m |

| 94. | Ranatunga, S.; Tang, C.-H. A.; Hu, C.-C. A.; Del Valle, J. R. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9859–9864. doi:10.1021/jo301723y |

| 9. | Mangeney, P.; Andriamialisoa, R. Z.; Langlois, N.; Langlois, Y.; Potier, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 2243–2245. doi:10.1021/ja00502a072 |

| 10. | Kutney, J. P.; Choi, L. S. L.; Nakano, J.; Tsukamoto, H.; McHugh, M.; Boulet, C. A. Heterocycles 1988, 27, 1845–1853. doi:10.3987/COM-88-4611 |

| 11. | Kuehne, M. E.; Matson, P. A.; Bornmann, W. G. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 513–528. doi:10.1021/jo00002a008 |

| 12. | Magnus, P.; Mendoza, J. S.; Stamford, A.; Ladlow, M.; Willis, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10232–10245. doi:10.1021/ja00052a020 |

| 13. | Yokoshima, S.; Ueda, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, A.; Kuboyama, T.; Tokuyama, H.; Fukuyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2137–2139. doi:10.1021/ja0177049 |

| 14. | Ishikawa, H.; Colby, D. A.; Seto, S.; Va, P.; Tam, A.; Kakei, H.; Rayl, T. J.; Hwang, I.; Boger, D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4904–4916. doi:10.1021/ja809842b |

| 72. | Zhang, X.; van der Donk, W. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2212–2213. doi:10.1021/ja067672v |

| 6. | Armstrong, R. W.; Beau, J. M.; Cheon, S. H.; Christ, W. J.; Fujioka, H.; Ham, W. H.; Hawkins, L. D.; Jin, H.; Kang, S. H.; Kishi, Y.; Martinelli, M. J.; McWhorter, W. W., Jr.; Mizuno, M.; Nakata, M.; Stutz, A. E.; Talamas, F. X.; Taniguchi, M.; Tino, J. A.; Ueda, K.; Uenishi, J.; White, J. B.; Yonaga, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7525–7530. doi:10.1021/ja00201a037 |

| 7. | Armstrong, R. W.; Beau, J. M.; Cheon, S. H.; Christ, W. J.; Fujioka, H.; Ham, W. H.; Hawkins, L. D.; Jin, H.; Kang, S. H.; Kishi, Y.; Martinelli, M. J.; McWhorter, W. W., Jr.; Mizuno, M.; Nakata, M.; Stutz, A. E.; Talamas, F. X.; Taniguchi, M.; Tino, J. A.; Ueda, K.; Uenishi, J.; White, J. B.; Yonaga, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7530–7533. doi:10.1021/ja00201a038 |

| 8. | Suh, E. M.; Kishi, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 11205–11206. doi:10.1021/ja00103a065 |

| 4. | Vaenkatesan, V.; Wegh, R. T.; Teunissen, J.-P.; Lub, J.; Bastiaansen, C. W. M.; Broer, D. J. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2005, 15, 138–142. doi:10.1002/adfm.200400122 |

| 5. | Zhuang, X. X.; Sun, X. X.; Li, L.; Li, Y. C. Adv. Mat. Res. 2011, 337, 151–154. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.337.151 |

| 71. | Dhondi, P. K.; Carberry, P.; Choi, L. B.; Chisholm, J. D. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9590–9596. doi:10.1021/jo701643h |

| 86. | Ribes, C.; Falomir, E.; Carda, M.; Marco, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7779–7782. doi:10.1021/jo8012989 |

| 87. | Mallesham, P.; Vijaykumar, B. V. D.; Shin, D.-S.; Chandrasekhar, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 6145–6147. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.09.034 |

| 2. | Ramos Tombo, G. M.; Belluš, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 1193–1215. doi:10.1002/anie.199111933 |

| 3. | Lamberth, C. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 7239–7256. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.06.008 |

| 71. | Dhondi, P. K.; Carberry, P.; Choi, L. B.; Chisholm, J. D. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9590–9596. doi:10.1021/jo701643h |

| 85. | Jeon, J.; Shin, M.; Yoo, J. W.; Oh, J. S.; Bae, J. G.; Jung, S. H.; Kim, Y. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 1105–1108. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.12.084 |

| 26. | Garner, P.; Park, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 2361–2364. doi:10.1021/jo00388a004 |

| 69. | Chun, J.; Byun, H.-S.; Bittman, R. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 348–354. doi:10.1021/jo026240+ |

| 24. | Garner, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 5855–5858. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)81703-2 |

| 25. | Garner, P.; Park, J. M. Org. Synth. 1990, 70, 18–28. |

| 70. | Yadav, J. S.; Geetha, V.; Krishnam Raju, A.; Gnaneshwar, D.; Chandrasekhar, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 2983–2985. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(03)00390-3 |

| 24. | Garner, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 5855–5858. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)81703-2 |

| 25. | Garner, P.; Park, J. M. Org. Synth. 1990, 70, 18–28. |