Abstract

The formation of soluble 1:2 complexes within hydrophilic γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD) thioethers allows to perform photodimerizations of aromatic guests under controlled, homogenous reaction conditions. The quantum yields for unsubstituted anthracene, acenaphthylene, and coumarin complexed in these γ-CD thioethers were found to be up to 10 times higher than in the non-complexed state. The configuration of the photoproduct reflected the configuration of the dimeric inclusion complex of the guest. Anti-parallel orientation of acenaphthylene within the CD cavity led to the exclusive formation of the anti photo-dimer in quantitative yield. Parallel orientation of coumarin within the complex of a CD thioether led to the formation of the syn head-to-head dimer. The degree of complexation of coumarin could be increased by employing the salting out effect.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Photochemical reactions have been considered highly attractive for a long time because they often lead to products that are otherwise virtually inaccessible by thermal reactions. The syntheses of highly strained molecules such as cubane [1] and pagodane [2] are famous examples. However, it is often difficult to predict and control the outcome of photochemical transformations in homogeneous media, and various mixtures of products are obtained. Pre-organization of the reactants in the solid state [3] or by various templates in solution has been the best solution to this problem [4,5].

Cyclic host molecules large enough to accommodate two reacting molecules are the smallest possible templates for the control of photoreactions. Such a host provides a well-defined nano environment, a so-called molecular reaction vessel [6], which can catalyze and direct particular transformations. Calixarenes [7], cucurbiturils [8,9], and cyclodextrins (CDs) [10-16] have already been employed in template controlled photoreactions. Among these hosts CDs offer the advantage of being soluble in water at neutral pH, which is the most favourable solvent for performing photoreactions because of its high transmittance and stability to UV light. Inclusion in CDs not only improves the quantum yields of photodimerizations but also gives rise to high regio- and stereo-selectivities [15-18] However, the application of native CDs for fully hydrophobic reactants is hampered by the fact that their inclusion compounds are nearly insoluble in water leading to undesirable heterogenous reaction conditions [19]. Yields of heterogenous photoreactions generally depend on the particle size of the educt phase because the penetration depth of the incident light is limited.

Recently, we synthesized a series of highly water-soluble per-6-deoxy-thioethers of β- and γ-CD, which are able to solubilize hydrophobic, nearly insoluble guest molecules, such as camptothecin [20], 1,4-dihydroxyanthraquinone [21], betulin [22], benzene and cyclohexane derivatives [23], and even C60 [24] in water. Furthermore, their respective γ-CD thioethers form highly water-soluble 1:2 complexes with polycyclic aromatics, such as naphthalene, anthracene (ANT), and acenaphthylene (ACE) [25]. In the following we report on the photochemistry of ANT, ACE and coumarin (COU), templated by complexation in several hydrophilic γ-CD thioethers 1–7 (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Special attention will be paid to both the quantum yields Φ and stereoselectivities of the photodimerizations.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of selected aromatic guests: anthracene, ANT; acenaphthylene, ACE; and coumarin, COU.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of selected aromatic guests: anthracene, ANT; acenaphthylene, ACE; and coumarin...

Figure 2: Structures of γ-CD and γ-CD thioethers 1–7.

Figure 2: Structures of γ-CD and γ-CD thioethers 1–7.

Results and Discussion

Photodimerization of anthracene

Due to the fact that the inclusion compounds of ANT in native β-CD or γ-CD are completely insoluble in water, only the aqueous photochemistry of hydrophilic ANT derivatives, such as anthracene-2-carboxylate (ANT-2-COONa) [12], and anthracene-2-sulfonate (ANT-2-SO3Na) [26], have been investigated so far. The quantum yields of photodimerization increase dramatically from 5 to up to 50% by complexation of these guests with β-CD or γ-CD, as found by Tamaki et al. [26,27]. Formation of 2:2 complexes with β-CD and 1:2 (host/guest) sandwich complexes with γ-CD were made responsible for the observed increase in the quantum yields.

The photodimerization of unmodified ANT could be performed for the first time homogenously in aqueous solution, because of the high solubilities of ANT complexed by γ-CD thioethers 1–7 in water. The highest concentration, [ANT] = 0.04 mM, was achieved with a 6 mM solution of host 1 [25]. The respective binding constants K [25], and quantum yields Φ for monochromatic irradiation, are listed in Table 1. The values of Φ in the presence of 6.0 mM γ-CD thioethers were very high (16–33%) depending on the side groups of the host. Derivative 4 with thiolactate side groups, performed best. The observed high quantum yields were attributed to the tight sandwich-like packing of the two ANT molecules within these hosts, which was already demonstrated previously by fluorescence measurements [25]. The quantum yield Φ did not correlate with the binding constant K, possibly because dissolved ANT is mainly converted in the complexed state in presence of hosts 1–7. Only a small portion of ANT remains in the free state due to its low solubility (0.4 μM, [25]). Instead, packing of the two ANT molecules within the complex seems to determine the quantum yield Φ.

Table 1: Influence of CDs on the quantum yield Φ of the photodimerization of ANT and 1:2 binding constant K [25].

| Hosta | Φb [%] | K/109 [M−2] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29 | 22.8 |

| 2 | 16 | 7.7 |

| 3 | 29 | 6.8 |

| 4 | 33 | 3.4 |

| 5 | 25 | 3.7 |

| 6 | 27 | 6.5 |

| 7 | 19 | 7.7 |

aConcentration of γ-CD thioethers 1–7 was 6.0 mM. bFor λ = 350 nm, experimental error ± 5 %.

Stereoselective photodimerization of acenaphthylene

The photodimerization of ACE generally leads to mixtures of two isomeric cyclobutane derivatives, namely the syn and the anti dimers, as shown in Scheme 1. The quantum yields for the reactions in both aqueous and organic media are known to be rather low, 1% < Φ < 5%, as summarized in Table 2 [28,29]. Only the addition of solvents with heavy atoms, such as ethyl iodide, leads to satisfactory quantum yields (up to 17%). This increase is accompanied by an increase in the relative amount of the anti isomer. The increases of both the quantum yield and amount of the anti product – called the heavy atom effect – was attributed to an increased population of triplet states [29-31]. Heavy atoms close to the excited entity accelerate the rate of spin-orbit coupling interactions between states of different spin multiplicities and consequently facilitate intersystem crossing. However, supramolecular control of the packing of ACE leads to a significant improvement of the stereoselectivity. ACE was complexed in a cavitand nanocapsule [32] and in a Pd nanocage [33] in aqueous solution, both giving rise to the exclusive formation of the syn isomer. Unfortunately, the quantum yields have not been reported for these systems so far.

Table 2: Quantum yields Φ, distributions of the photodimers, and binding constants K [25] of ACE for various reaction media.

aThis work, host concentration 6 mM. bFor λ = 300 nm, experimental error ±5%. cExperimental error ±2%.

ACE also formed inclusion compounds with β-CD thioethers 1–7, which are soluble in aqueous medium. The highest concentrations of ACE, [ACE] = 1.7 and 1.3 mM, were achieved with 6 mM solutions of hosts 3 and 6, respectively. The photodimerization of ACE complexed in hosts 3 and 6 proceeded under homogenous conditions and furnished nearly quantitatively the anti isomer within 12 h. The quantum yields, reaching Φ = 28%, were unprecedentedly high, significantly higher than that of free ACE in organic solvents such as toluene (5%), ethanol (4%), and methanol/water (20% v/v, 3%) [28]. The 1H NMR signals of cyclobutane (for the syn photodimer, δH = 4.84 ppm; for the anti photodimer, δH = 4.10 ppm) were monitored to analyze the isomeric ratio [34,35]. As shown in Figure 3, only the proton signal at δH = 4.10 ppm was observed indicating the exclusive formation of the dimer in the anti configuration.

![[1860-5397-9-217-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-217-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: 1H NMR spectrum of the photo product of ACE in the presence of γ-CD thioether 3 in CDCl3.

Figure 3: 1H NMR spectrum of the photo product of ACE in the presence of γ-CD thioether 3 in CDCl3.

Because other hosts favored the syn dimer, the total preference of the anti dimer was indeed surprising at first, but there are several explanations for the observed anti specificity:

(a) ACE is tightly surrounded by the seven sulfur atoms of host 3, which may lead to an increased population of the triplet state and consequently to a heavy atom effect, which favors the formation of the anti dimer. Other CD derivatives with heavy atoms attached, e.g., 6-deoxy-iodo-CDs, are known to even enable room temperature phosphorescence of an excited guest [36].

(b) Moreover, according to the results of the quantum mechanical calculations [25,34] the preferential anti-parallel alignment of the ACE dimer within the CD cavity also favors the formation of the anti dimer.

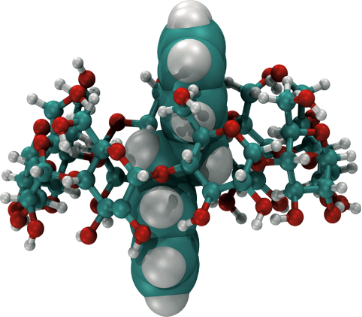

(c) The anti dimer appears to better fit into the γ-CD cavity than the syn isomer, as depicted in Figure 4.

![[1860-5397-9-217-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-217-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Schematic drawing of the ACE photodimers in γ-CD: a) the syn photodimer and b) the anti photodimer. The rendering was performed with VMD 1.8.7 [37].

Figure 4: Schematic drawing of the ACE photodimers in γ-CD: a) the syn photodimer and b) the anti photodimer....

Stereoselective photodimerization of coumarin

The photochemistry of COU and its derivatives is rather complex because the quantum yield and distribution of products strongly depend both on the solvent [38] and the concentration of COU [39]. In principle, four stereoisomeric dimers are conceivable: syn Head-to-Head (syn-HH), anti-HH, syn-Head-to-Tail (syn-HT), and anti-HH, shown in Figure 5. The photodimerization is very slow in nonpolar media, Φ < 10−3% and mainly leading to the anti-HH dimer [39]. In contrast, polar protic solvents, like water, increase both the quantum yield and the amount of the syn-HH dimer, exemplified in Table 3. The singlet state has a very short lifetime because of rapid intersystem crossing and self-quenching and it reacts to form the syn-HH dimer, while the triplet state, with a longer lifetime, furnishes the anti-HH isomer [38,40]. Because most often mixtures of syn and anti isomers were obtained after irradiation of COU, any supramolecular control of the dimerization was highly desirable.

Table 3: Distribution of the photodimers of COU for various media.

| Host | Product distribution [%]a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| syn-HH | anti-HH | syn-HT | syn/anti | |

| water | 59 | 9 | 32 | 10 |

| γ-CDb | 52 | 17 | 31 | 4.7 |

| 1b | 58 | 16 | 26.5 | 5.4 |

| 2b | 87 | 5 | 8.4 | 19.8 |

| 3b | 57 | 16 | 26.6 | 5.1 |

| 4b | 71 | 8 | 20.9 | 11.8 |

| 5b | 72 | 9 | 19.1 | 10.0 |

| 6b | 71 | 10 | 18.5 | 8.6 |

| 7b | 51 | 10 | 38.6 | 8.5 |

aExperimental error ± 3%. b6 mM solutions in water.

Photodimerization of a 15 mM aqueous solution of COU proceeded with a low quantum yield Φ = 0.11% and afforded mainly the syn-HH isomer with a reasonable selectivity of syn/anti = 10, as previously described [38,39]. Photodimerization of 6-methyl-COU complexed in cucurbituril CB [8] furnished the syn-HT isomer as the main product [41,42]. The analogous effect of β-CD was investigated by Moorthy et al. in 1992. They isolated the syn-HH dimer in 64% yield after irradiation for 135 h of the crystalline (2:2) inclusion compound of COU in β-CD [43]. Therefore, it was very interesting to investigate the supramolecular control exerted by γ-CD thioethers 1–7 in aqueous solution. The composition of the mixture of isomeric photodimers was determined from the intensities of the 1H NMR signals of the cyclobutane protons, which were assigned according to previous work [40]. The results including the respective syn/anti ratios are listed in Table 3. In comparison, a 6 mM solution of native γ-CD caused a diminished selectivity of syn/anti = 4.7.

Surprisingly, the γ-CD thioethers did not behave uniformly. The anionic host 2 increased the selectivity of syn/anti to 19.8, while the cationic host 1 produced low selectivity, similar to the native γ-CD. The 87% yield of the syn-HH dimer obtained with the best host 2 was still not sufficient for any preparative application.

The lower stereoselectivity of the photodimerization of COU compared to that of ACE, which was achieved with the γ-CD thioethers, was attributed to the much higher aqueous solubility of COU (15 mM) compared to the solubility of ACE (0.067 mM) [25]. Because the concentration of the free guest [G]free is determined by two coupled thermodynamic equilibria (Equation 1). The 2-phase solubility equilibrium is expressed by Equation 2 and the equilibrium of complexation by the CD host is formulated in Equation 3. The guest dissolves until the concentration of free guest is equal to the solubility of the guest, [G]0 = [G]free [44,45]. Consequently, the lower the solubility of the guest in water, the lower the fraction of uncomplexed guests. The lower the concentration of the free guest, the lower the contribution of undesirable and non-specific photodimerization to the total quantum yield, according to Equation 4. Consequently, lowering the aqueous solubility of COU by the addition of salt, taking advantage of the so-called “salting-out effect” [46] appeared to be a plausible way to enhance the reaction selectivity of the syn-HH dimer.

The 1H NMR spectra of the crude photoproducts indeed showed a striking effect from changes in the salt concentration. The signals of the syn-HT and anti-HH isomers significantly diminished as shown in Figure 6. At a high salt concentration, [Na2SO4] = 1.5 M, almost pure syn-HH dimer was formed exclusively. The compositions, obtained from the NMR intensities, are listed in Table 4. The observed improvement in the quantum yield and stereoselectivity by the addition of salt was quantitatively described taking into account the decrease of the solubility of COU by the salting-out effect. As shown in Table 5, the aqueous solubility of COU is diminished by nearly a factor of 6 as a result of raising the salt concentration to 1.5 M. In parallel, the quantum yield Φfree of free COU is diminished approximately linearly from 2.2% to 1.2%.

![[1860-5397-9-217-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-217-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Partial 1H NMR of the photodimers formed after irradiation of COU at various concentrations of Na2SO4 in the presence of 6 mM γ-CD thioether 2.

Figure 6: Partial 1H NMR of the photodimers formed after irradiation of COU at various concentrations of Na2SO...

Table 4: Influence of the sodium sulfate concentration on the quantum yield Φ and distribution of photoproducts of COU in a 6.0 mM solution of γ-CD thioether 2.

| [Na2SO4] | Φa | Product distribution [%]b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | % | syn-HH | anti-HH | syn-HT |

| 0.0 | 3.8 | 86 | 5 | 9 |

| 0.5 | 89 | 0 | 11 | |

| 1.0 | 95 | 0 | 5 | |

| 1.5 | 13.0 | 97 | 0 | 3 |

aFor λ = 300 nm, experimental error ±3%. bExperimental error ±2%.

Both effects based on the salt concentration led to a significant reduction in the contribution of the photodimerization of free COU to the total quantum yield Φ in Equation 4. Taking into account the molar fraction of the formation of syn-HH in water from Table 3 and in the complex

, and assuming the quantum yield for the complex as Φcomplex = 19%, the total molar fraction

was calculated according to Equation 5, which was derived from Equation 4. The concentration of complexed COU, [COU]C, was determined as the increase in the solubility of COU upon the addition of the host. The calculated total quantum yields and molar fractions of the syn-HH isomer, listed in Table 5, are in good agreement with the measured values, listed in Table 4. It also shoes, that the binding constant K, calculated according to the law of mass action for the 1:2 (host/guest) complex, tremendously increases with the salt concentration leading to a strong increase of the complexed portion of COU. In contrast to the previous ANT system, the quantum yield of COU photodimerization increases with the binding const K, because K is much lower for COU than for ANT so that contribution of free COU is not negligible.

Table 5: The quantum yields, calculated according to (4) and the fractions of the syn-HH dimer, calculated according to (5), for the photodimerization of COU in a 6.0 mM solution of γ-CD thioether 2 and binding constant K as a function of salt concentration.

|

[Na2SO4]

M |

[COU]0

mM |

[COU]C

mM |

Φcalc

% |

% |

K/103

M−2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 15.2 | 3.1 | 5.0 | 85 | 2 |

| 0.5 | 8.5 | 4.8 | 94 | 30 | |

| 1.0 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 97 | 97 | |

| 1.5 | 2.6 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 99 | 1000 |

[COU]0 solubility of COU, [COU]C concentration of complexed COU, K binding constant of COU complexed in 2 from solubility measurements.

As a result, the syn-HH isomer is exclusively formed from the complex with CD derivative 2, with a quantum yield approximately ten times higher than that observed without complexation. The tight packing of the two COU molecules within the host was made responsible for the significantly increased quantum yield. The heavy atom effect of the S-atoms of CD derivatives 1–7 should facilitate intersystem crossing to the triplet state and therefore support the formation of the anti-HH dimer. Because this preference does not hold true in this case, especially for host 2, the multiplicity of the excited state seems not to be the dominant factor, but rather the pre-organization of the guest molecules in the CD cavity prior to excitation has the greatest effect. The distribution of the stereoisomers appears to be mainly topochemically [5] controlled because of the short lifetime of the excited state of COU.

Quantum mechanical calculations of the structures and interaction energies ΔE of the four COU dimers were performed using the Gaussian 03 software package to investigate the favored packing [47]. The aromatic dimers were fully optimized at the MP2/6-31G* level without any symmetry restriction during the computation. The interaction energies ΔE of the syn-HH, anti-HH, syn-HT, and anti-HT dimers of COU were −32.9, −29.3, −24.0, and −22.5 kJ∙mol−1, respectively. The ΔE value of the COU dimer with the syn-HH orientation was found to be significantly more negative than that of the dimer with the other orientation. This result can be attributed to relatively efficient π–π stacking [48] The most stable syn-HH dimeric aggregate forms the most stable, and therefore, most abundant complex within the γ-CD cavity and consequently the main photo-product. Hence, the photodimerization of COU within host 2 is a topochemical reaction. This type of topochemical control happening in solution is much more applicable than the classical topochemical control occurring in the crystalline state [3,43,49].

Conclusion

Aromatic guests ANT, ACE, and COU form 1:2 (host/guest) complexes within γ-CD thioethers 1–7, which photodimerized approximately 10 times faster in aqueous medium than the same uncomplexed guests in aqueous solution. Since these photo dimerizations of hydrophobic guests are performable at neutral pH in optically clear solution in water they are suitable for preparative applications. Isolation of the photoproduct from aqueous solution by liquid/liquid extraction simplifies the scale up. Yields of photodimer based on the complex were nearly quantitative.

The observed supramolecular catalysis was explained by the high pre-organization resulting from the tight packing of the two guests in the cavity, which allows for photoreactions even for short-lived excited states. In comparison to other confined and ordered media, most γ-CD thioether complexes offer the advantages of very high quantum yields and excellent stereochemical control. Because the product formation is mainly topochemically controlled, photoproducts are predictable by quantum mechanical optimization of the corresponding dimeric aggregates in vacuo.

This work also showed that the addition of salt can further improve supramolecular control by suppression of the free photoactive species.

Experimental

General: Guests (ANT, ACE, and COU) and potassium ferrioxalate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were used as received. γ-CD was donated by Wacker and dried in vacuo at 100 °C overnight before use. The γ-CD thioethers were synthesized as previously described [25] and purified by nanofiltration (molecular weight cut-off of 1000 Da with demineralized water). Teflon syringe filters (0.22 μm) from Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany) were used to remove insoluble material before taking UV–vis and fluorescence measurements and the photoirradiation experiments. The UV–vis spectra of aqueous samples were taken on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 2 spectrometer (λ: 200–600 nm) using quartz cells with a 1 cm or 1 mm optical path at 298 K. The fluorescence spectra were recorded in a JASCO spectrophotometer using quartz cells of 10.0 mm path at 298 K. All of the NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 MHz NMR spectrometer at 298 K using the solvent peaks as internal references, and the coupling constants (J) were measured in Hz.

Photoreaction procedures: Aqueous solutions of the native CDs or γ-CD thioethers (25 mL, 6.0 mM) were added into glass vials containing excess amounts of the guest molecules. To evaluate the salting-out effect on the photo-product distribution of COU, different amounts of sodium sulfate were added to the vials to obtain the desired final salt concentration (Na2SO4 concentration: 0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 M). Sample solutions were thoroughly degassed using sonication. The vials were tightly sealed, protected from light, and magnetically stirred at room temperature. After 72 h, the resulting suspensions were filtered through syringe filters. The concentrations of the reactants in the CD solutions were determined from the UV–vis extinction coefficients at the absorption maxima.

The aqueous solutions of the inclusion complexes were transferred into 50 mL quartz round-bottomed flasks and bubbled with nitrogen gas for 20 min with stirring before photo-irradiation. Photodimerization of the samples was carried out using a medium-pressure mercury lamp (166.5 W, Heraeus Noblelight GmbH, UVB) as a light source. After irradiation for 12 h at room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere, the photoproducts formed were extracted with chloroform and then analyzed by 1H NMR [34]. No starting material was found anymore after this time of reaction. It is worth mentioning that a precipitate was formed after irradiation of the aqueous solution of the inclusion complex of ACE with γ-CD thioether.

Molecular modeling: A previously described procedure was used [25]. The geometries of the orientational isomers of the COU gas-phase dimer were fully optimized without any symmetry restriction at the MP2/6-31G* level of theory by using the Gaussian 03 (E.01) software package [47]. Corrected interaction energies (∆E) corresponding to the optimized aromatic dimers were evaluated using the equation ∆E = Edimer – 2Emonomer at the MP2/6-31G* level, where Edimer and Emonomer are the energies of the aromatic dimer and the monomer, respectively [50].

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Quantum yield measurement. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 167.8 KB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank the technical support from Annegret Engelke. We would also like to express our appreciation to Dagmar Auerbach, Christian Spies, and Prof. Dr. Gregor Jung from Saarland University (Biophysikalische Chemie) for their assistance in quantum yield measurements. Financial support from Saarland University and China Scholarship Council are gratefully acknowledged.

References

-

Eaton, P. E.; Cole, T. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3157–3158. doi:10.1021/ja01069a041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fessner, W. D.; Sedelmeier, G.; Spurr, P. R.; Rihs, G.; Prinzbach, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 4626–4642. doi:10.1021/ja00249a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schmidt, G. Pure Appl. Chem. 1971, 27, 647–678. doi:10.1351/pac197127040647

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ramamurthy, V. Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 5753–5839. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)96063-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Svoboda, J.; König, B. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 5413–5430. doi:10.1021/cr050568w

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Murase, T.; Fujita, M. Chem. Rec. 2010, 10, 342–347. doi:10.1002/tcr.201000027

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kaliappan, R.; Ling, Y.; Kaifer, A. E.; Ramamurthy, V. Langmuir 2009, 25, 8982–8992. doi:10.1021/la900659r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jon, S. Y.; Ko, Y. H.; Park, S. H.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, K. Chem. Commun. 2001, 1938–1939. doi:10.1039/B105153A

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chen, B.; Cheng, S.-F.; Liao, G.-H.; Li, X.-W.; Zhang, L.-P.; Tung, C.-H.; Wu, L.-Z. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2011, 10, 1441–1444. doi:10.1039/c1pp05047h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Herrmann, W.; Wehrle, S.; Wenz, G. Chem. Commun. 1997, 1709–1710. doi:10.1039/A703485G

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rao, K. S. S. P.; Hubig, S. M.; Moorthy, J. N.; Kochi, J. K. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 8098–8104. doi:10.1021/jo9903149

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nakamura, A.; Inoue, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 966–972. doi:10.1021/ja016238k

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Douhal, A. Cyclodextrin materials photochemistry, photophysics and photobiology; Elsevier Science, 2006; Vol. 1.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, L.; Liao, G.-H.; Wu, X.-L.; Lei, L.; Tung, C.-H.; Wu, L.-Z. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 3506–3515. doi:10.1021/jo900395v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, C.; Nakamura, A.; Fukuhara, G.; Origane, Y.; Mori, T.; Wada, T.; Inoue, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3126–3136. doi:10.1021/jo0601718

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yang, C.; Ke, C.; Liang, W.; Fukuhara, G.; Mori, T.; Liu, Y.; Inoue, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13786–13789. doi:10.1021/ja202020x

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ramamurthy, V.; Eaton, D. F. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988, 21, 300–306. doi:10.1021/ar00152a003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, C.; Fukuhara, G.; Nakamura, A.; Origane, Y.; Fujita, K.; Yuan, D. Q.; Mori, T.; Wada, T.; Inoue, Y. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A: Chem. 2005, 173, 375–383. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2005.04.017

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sanemasa, I.; Wu, J. S.; Toda, K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1997, 70, 365–369. doi:10.1246/bcsj.70.365

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Steffen, A.; Thiele, C.; Tietze, S.; Strassnig, C.; Kämper, A.; Lengauer, T.; Wenz, G.; Apostolakis, J. Chem.–Eur. J. 2007, 13, 6801–6809. doi:10.1002/chem.200700661

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Thiele, C.; Auerbach, D.; Jung, G.; Wenz, G. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2011, 69, 303–307. doi:10.1007/s10847-010-9741-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H. M.; Soica, C. M.; Wenz, G. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 289–291.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fourmentin, S.; Ciobanu, A.; Landy, D.; Wenz, G. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 1185–1191. doi:10.3762/bjoc.9.133

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 1644–1651. doi:10.3762/bjoc.8.188

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] -

Tamaki, T.; Kokubu, T.; Ichimura, K. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 1485–1494. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90264-9

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Tamaki, T.; Kokubu, T. J. Inclusion Phenom. 1984, 2, 815–822. doi:10.1007/BF00662250

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Livingston, R.; Wei, K. S. J. Phys. Chem. 1967, 71, 541–547. doi:10.1021/j100862a012

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Cowan, D. O.; Koziar, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 1229–1230. doi:10.1021/ja00811a049

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cowan, D. O.; Drisko, R. L. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 6281–6285. doi:10.1021/ja00724a029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cowan, D. O.; Drisko, R. L. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 6286–6291. doi:10.1021/ja00724a030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kaanumalle, L. S.; Ramamurthy, V. Chem. Commun. 2007, 1062–1064. doi:10.1039/b615937k

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yoshizawa, M.; Takeyama, Y.; Kusukawa, T.; Fujita, M. Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 1403–1405. doi:10.1002/1521-3757(20020415)114:8<1403::AID-ANGE1403>3.0.CO;2-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Santos, R. C.; Bernardes, C. E. S.; Diogo, H. P.; Piedade, M. F. M.; Lopes, J. N. C.; da Piedade, M. E. M. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 2299–2307. doi:10.1021/jp056275o

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Bhat, S.; Maitra, U. Molecules 2007, 12, 2181–2189. doi:10.3390/12092181

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hamai, S.; Kudou, T. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 1998, 113, 135–140.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. doi:10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wolff, T.; Gorner, H. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 368–376. doi:10.1039/b312335a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Muthuramu, K.; Ramamurthy, V. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 3976–3979. doi:10.1021/jo00141a035

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Yu, X. L.; Scheller, D.; Rademacher, O.; Wolff, T. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7386–7399. doi:10.1021/jo034627m

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Barooah, N.; Pemberton, B. C.; Sivaguru, J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3339–3342. doi:10.1021/ol801256r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pemberton, B. C.; Singh, R. K.; Johnson, A. C.; Jockusch, S.; Da Silva, J. P.; Ugrinov, A.; Turro, N. J.; Srivastava, D. K.; Sivaguru, J. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6323–6325. doi:10.1039/c1cc11164g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moorthy, J. N.; Venkatesan, K.; Weiss, R. G. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 3292–3297. doi:10.1021/jo00038a012

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Higuchi, T.; Connors, K. Adv. Anal. Chem. Instrum. 1965, 4, 117–212.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Connors, K. A. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1325–1357. doi:10.1021/cr960371r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sau, S.; Solanki, B.; Orprecio, R.; Van Stam, J.; Evans, C. H. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2004, 48, 173–180. doi:10.1023/B:JIPH.0000022556.47230.c8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gaussian 03, Revision E. 01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2004.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Guckian, K.; Schweitzer, B.; Ren, R. X.-F.; Sheils, C.; Tahmassebi, D.; Kool, E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 2213–2222. doi:10.1021/ja9934854

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wenz, G.; Wegner, G. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1983, 96, 99–108. doi:10.1080/00268948308074696

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boys, S. F.; Bernardi, F. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. doi:10.1080/00268977000101561

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 33. | Yoshizawa, M.; Takeyama, Y.; Kusukawa, T.; Fujita, M. Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 1403–1405. doi:10.1002/1521-3757(20020415)114:8<1403::AID-ANGE1403>3.0.CO;2-6 |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 32. | Kaanumalle, L. S.; Ramamurthy, V. Chem. Commun. 2007, 1062–1064. doi:10.1039/b615937k |

| 38. | Wolff, T.; Gorner, H. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 368–376. doi:10.1039/b312335a |

| 39. | Muthuramu, K.; Ramamurthy, V. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 3976–3979. doi:10.1021/jo00141a035 |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 34. | Santos, R. C.; Bernardes, C. E. S.; Diogo, H. P.; Piedade, M. F. M.; Lopes, J. N. C.; da Piedade, M. E. M. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 2299–2307. doi:10.1021/jp056275o |

| 37. | Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. doi:10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 |

| 34. | Santos, R. C.; Bernardes, C. E. S.; Diogo, H. P.; Piedade, M. F. M.; Lopes, J. N. C.; da Piedade, M. E. M. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 2299–2307. doi:10.1021/jp056275o |

| 35. | Bhat, S.; Maitra, U. Molecules 2007, 12, 2181–2189. doi:10.3390/12092181 |

| 28. | Livingston, R.; Wei, K. S. J. Phys. Chem. 1967, 71, 541–547. doi:10.1021/j100862a012 |

| 28. | Livingston, R.; Wei, K. S. J. Phys. Chem. 1967, 71, 541–547. doi:10.1021/j100862a012 |

| 39. | Muthuramu, K.; Ramamurthy, V. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 3976–3979. doi:10.1021/jo00141a035 |

| 38. | Wolff, T.; Gorner, H. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 368–376. doi:10.1039/b312335a |

| 40. | Yu, X. L.; Scheller, D.; Rademacher, O.; Wolff, T. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7386–7399. doi:10.1021/jo034627m |

| 38. | Wolff, T.; Gorner, H. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 368–376. doi:10.1039/b312335a |

| 39. | Muthuramu, K.; Ramamurthy, V. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 3976–3979. doi:10.1021/jo00141a035 |

| 46. | Sau, S.; Solanki, B.; Orprecio, R.; Van Stam, J.; Evans, C. H. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2004, 48, 173–180. doi:10.1023/B:JIPH.0000022556.47230.c8 |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 44. | Higuchi, T.; Connors, K. Adv. Anal. Chem. Instrum. 1965, 4, 117–212. |

| 45. | Connors, K. A. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1325–1357. doi:10.1021/cr960371r |

| 43. | Moorthy, J. N.; Venkatesan, K.; Weiss, R. G. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 3292–3297. doi:10.1021/jo00038a012 |

| 40. | Yu, X. L.; Scheller, D.; Rademacher, O.; Wolff, T. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7386–7399. doi:10.1021/jo034627m |

| 8. | Jon, S. Y.; Ko, Y. H.; Park, S. H.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, K. Chem. Commun. 2001, 1938–1939. doi:10.1039/B105153A |

| 41. | Barooah, N.; Pemberton, B. C.; Sivaguru, J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3339–3342. doi:10.1021/ol801256r |

| 42. | Pemberton, B. C.; Singh, R. K.; Johnson, A. C.; Jockusch, S.; Da Silva, J. P.; Ugrinov, A.; Turro, N. J.; Srivastava, D. K.; Sivaguru, J. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6323–6325. doi:10.1039/c1cc11164g |

| 48. | Guckian, K.; Schweitzer, B.; Ren, R. X.-F.; Sheils, C.; Tahmassebi, D.; Kool, E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 2213–2222. doi:10.1021/ja9934854 |

| 3. | Schmidt, G. Pure Appl. Chem. 1971, 27, 647–678. doi:10.1351/pac197127040647 |

| 43. | Moorthy, J. N.; Venkatesan, K.; Weiss, R. G. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 3292–3297. doi:10.1021/jo00038a012 |

| 49. | Wenz, G.; Wegner, G. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1983, 96, 99–108. doi:10.1080/00268948308074696 |

| 1. | Eaton, P. E.; Cole, T. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3157–3158. doi:10.1021/ja01069a041 |

| 24. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 1644–1651. doi:10.3762/bjoc.8.188 |

| 4. | Ramamurthy, V. Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 5753–5839. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)96063-6 |

| 5. | Svoboda, J.; König, B. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 5413–5430. doi:10.1021/cr050568w |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 50. | Boys, S. F.; Bernardi, F. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. doi:10.1080/00268977000101561 |

| 2. | Fessner, W. D.; Sedelmeier, G.; Spurr, P. R.; Rihs, G.; Prinzbach, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 4626–4642. doi:10.1021/ja00249a029 |

| 23. | Fourmentin, S.; Ciobanu, A.; Landy, D.; Wenz, G. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 1185–1191. doi:10.3762/bjoc.9.133 |

| 15. | Yang, C.; Nakamura, A.; Fukuhara, G.; Origane, Y.; Mori, T.; Wada, T.; Inoue, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3126–3136. doi:10.1021/jo0601718 |

| 16. | Yang, C.; Ke, C.; Liang, W.; Fukuhara, G.; Mori, T.; Liu, Y.; Inoue, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13786–13789. doi:10.1021/ja202020x |

| 17. | Ramamurthy, V.; Eaton, D. F. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988, 21, 300–306. doi:10.1021/ar00152a003 |

| 18. | Yang, C.; Fukuhara, G.; Nakamura, A.; Origane, Y.; Fujita, K.; Yuan, D. Q.; Mori, T.; Wada, T.; Inoue, Y. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A: Chem. 2005, 173, 375–383. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2005.04.017 |

| 20. | Steffen, A.; Thiele, C.; Tietze, S.; Strassnig, C.; Kämper, A.; Lengauer, T.; Wenz, G.; Apostolakis, J. Chem.–Eur. J. 2007, 13, 6801–6809. doi:10.1002/chem.200700661 |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 10. | Herrmann, W.; Wehrle, S.; Wenz, G. Chem. Commun. 1997, 1709–1710. doi:10.1039/A703485G |

| 11. | Rao, K. S. S. P.; Hubig, S. M.; Moorthy, J. N.; Kochi, J. K. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 8098–8104. doi:10.1021/jo9903149 |

| 12. | Nakamura, A.; Inoue, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 966–972. doi:10.1021/ja016238k |

| 13. | Douhal, A. Cyclodextrin materials photochemistry, photophysics and photobiology; Elsevier Science, 2006; Vol. 1. |

| 14. | Luo, L.; Liao, G.-H.; Wu, X.-L.; Lei, L.; Tung, C.-H.; Wu, L.-Z. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 3506–3515. doi:10.1021/jo900395v |

| 15. | Yang, C.; Nakamura, A.; Fukuhara, G.; Origane, Y.; Mori, T.; Wada, T.; Inoue, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3126–3136. doi:10.1021/jo0601718 |

| 16. | Yang, C.; Ke, C.; Liang, W.; Fukuhara, G.; Mori, T.; Liu, Y.; Inoue, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13786–13789. doi:10.1021/ja202020x |

| 21. | Thiele, C.; Auerbach, D.; Jung, G.; Wenz, G. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2011, 69, 303–307. doi:10.1007/s10847-010-9741-4 |

| 8. | Jon, S. Y.; Ko, Y. H.; Park, S. H.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, K. Chem. Commun. 2001, 1938–1939. doi:10.1039/B105153A |

| 9. | Chen, B.; Cheng, S.-F.; Liao, G.-H.; Li, X.-W.; Zhang, L.-P.; Tung, C.-H.; Wu, L.-Z. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2011, 10, 1441–1444. doi:10.1039/c1pp05047h |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 7. | Kaliappan, R.; Ling, Y.; Kaifer, A. E.; Ramamurthy, V. Langmuir 2009, 25, 8982–8992. doi:10.1021/la900659r |

| 19. | Sanemasa, I.; Wu, J. S.; Toda, K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1997, 70, 365–369. doi:10.1246/bcsj.70.365 |

| 34. | Santos, R. C.; Bernardes, C. E. S.; Diogo, H. P.; Piedade, M. F. M.; Lopes, J. N. C.; da Piedade, M. E. M. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 2299–2307. doi:10.1021/jp056275o |

| 26. | Tamaki, T.; Kokubu, T.; Ichimura, K. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 1485–1494. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90264-9 |

| 27. | Tamaki, T.; Kokubu, T. J. Inclusion Phenom. 1984, 2, 815–822. doi:10.1007/BF00662250 |

| 12. | Nakamura, A.; Inoue, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 966–972. doi:10.1021/ja016238k |

| 26. | Tamaki, T.; Kokubu, T.; Ichimura, K. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 1485–1494. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90264-9 |

| 29. | Cowan, D. O.; Koziar, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 1229–1230. doi:10.1021/ja00811a049 |

| 30. | Cowan, D. O.; Drisko, R. L. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 6281–6285. doi:10.1021/ja00724a029 |

| 31. | Cowan, D. O.; Drisko, R. L. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 6286–6291. doi:10.1021/ja00724a030 |

| 32. | Kaanumalle, L. S.; Ramamurthy, V. Chem. Commun. 2007, 1062–1064. doi:10.1039/b615937k |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 28. | Livingston, R.; Wei, K. S. J. Phys. Chem. 1967, 71, 541–547. doi:10.1021/j100862a012 |

| 29. | Cowan, D. O.; Koziar, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 1229–1230. doi:10.1021/ja00811a049 |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

| 25. | Wang, H. M.; Wenz, G. Chem.–Asian J. 2011, 2390–2399. doi:10.1002/asia.201100217 |

© 2013 Wang and Wenz; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)