Abstract

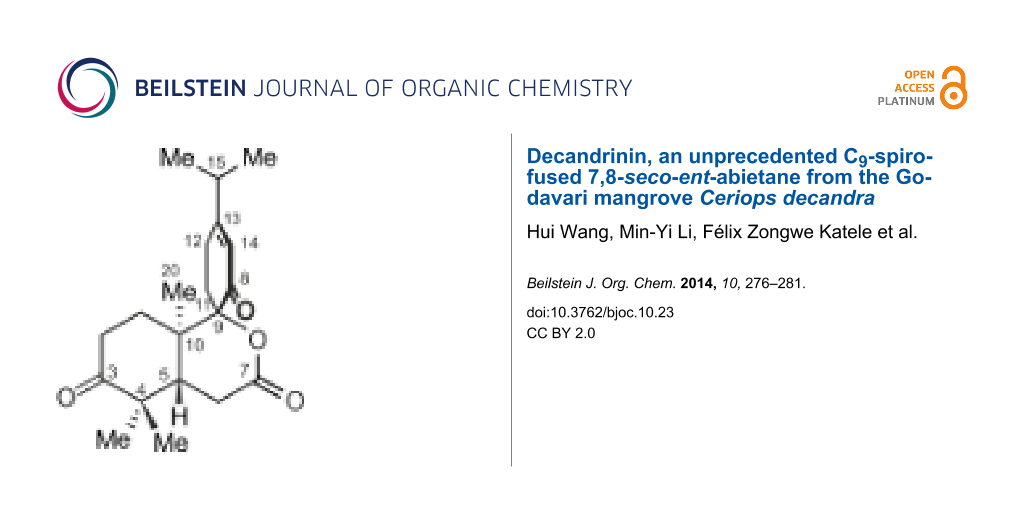

Decandrinin (1), an unprecedented C9-spiro-fused 7,8-seco-ent-abietane, was obtained from the bark of an Indian mangrove, Ceriops decandra, collected in the estuary of Godavari, Andhra Pradesh. The constitution and the relative configuration of 1 were determined by HRMS (ESI) and extensive NMR investigations, and the absolute configuration by circular dichroism (CD) and optical-rotatory dispersion (ORD) spectroscopy in combination with quantum-chemical calculations. Decandrinin is the first 7,8-seco-ent-abietane.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Ceriops decandra is a mangrove of the family Rhizophoraceae. It is widely distributed along the sea coasts of South Asia down to the southern pacific islands, and of Africa and Madagascar. The genus Ceriops only consists of five mangrove plant species. Besides C. decandra, these are C. australis, C. pseudodecandra, C. tagal, and C. zippeliana [1-4]. In Indian traditional medicine, the bark of C. decandra have been used for the treatment of amoebiasis, diarrhea, hemorrhage, and malignant ulcers [5], making it rewarding to screen the bioactive compounds of this plant. Before our work, already 28 compounds had been isolated from C. decandra [6] (three pimaranes, four beyeranes, five kauranes, and 16 lupanes). Recently, some of us have reported on the isolation of eleven new diterpenes from this plant, named decandrins A–K [7], of which nine belong to the group of abietanes.

Seco-abietane diterpenoids are a small group of natural products. To date, a total of 58 such compounds have been reported from plants of the genera Abies, Cephalotaxus, Colus, Cordia, Hyptis, Isodon, Pinus, Premna, Salvia, Taiwania, Thuja, and Vitex, including a 1,2-seco-abietane [8], a 1,10-seco-abietane [9,10], three 2,3-seco-abietanes [8,11-13], three 3,4-seco-abietanes [8,14], 31 4,5-seco-abietanes [8,15,16], ten 6,7-seco-abietanes [8,17-19], two 7,8-seco-abietanes [8,20], two 8,14-seco-abietanes [21,22], three 9,10-seco-abietanes [22,23], and two 9,11-seco-abietanes [24,25]. Among the above seco-abietanes, only laxiflorin V is a seco-ent-abietane [14]. Herein, we report on the isolation and structural elucidation of an unprecedented C9-spiro-fused 7,8-seco-ent-abietane, named decandrinin (1) (Figure 1), from the bark of an Indian mangrove, C. decandra, collected in the estuary of Godavari, Andhra Pradesh. The absolute stereostructure of 1 was established by HRMS (ESI), extensive NMR investigations, and by circular dichroism (CD) and optical-rotatory dispersion (ORD) spectroscopy in combination with quantum-chemical calculations.

Results and Discussion

Decandrinin (1) was obtained as a colorless solid. Its molecular formula was established as C20H28O4 by HRMS (ESI) (m/z 333.2053, calcd for [M + H]+, 333.2060). From this formula, it was suggested that 1 has seven degrees of unsaturation, of which four could be ascribed to one carbon–carbon double bond, one lactone carbonyl group, and two ketone groups, according to its 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1); the molecule should thus be tricyclic.

Table 1: 1H (400 MHz) and 13C (100 MHz) NMR spectroscopic data for 1 in CDCl3 (δ ppm).

| Position | δH (J in Hz) | δC |

|---|---|---|

| 1α | 1.87, m | 31.5, CH2 |

| 1β | 2.03, m | |

| 2α | 2.33, m | 33.8, CH2 |

| 2β | 2.68, m | |

| 3 | 213.1, C | |

| 4 | 47.1, C | |

| 5 | 2.47, m | 43.1, CH |

| 6α | 2.66, m | 28.8, CH2 |

| 6β | 2.47, m | |

| 7 | 170.9, C | |

| 8 | 195.9, C | |

| 9 | 88.3, C | |

| 10 | 39.0, C | |

| 11α | 2.59, m | 30.1, CH2 |

| 11β | 2.23, m | |

| 12 | 2.52, m | 26.6, CH2 |

| 2.52, m | ||

| 13 | 172.0, C | |

| 14 | 6.03, br s | 124.1, CH |

| 15 | 2.45, m | 35.4, CH |

| 16 | 1.11, d (6.9) | 20.6, CH3 |

| 17 | 1.11, d (6.9) | 20.8, CH3 |

| 18 | 1.06, s | 25.4, CH3 |

| 19 | 1.13, s | 21.6, CH3 |

| 20 | 1.37, s | 14.9, CH3 |

The NMR data and a DEPT experiment (Table 1) indicated the presence of an olefinic methine group [δH 6.03 (br s), δC 124.1], two aliphatic methine groups [δH 2.47 (m), δC 43.1; δH 2.45 (m), δC 35.4], five methylene groups [δH 2.33 (m), 2.68 (m), δC 33.8; δH 1.87 (m), 2.03 (m), δC 31.5; δH 2.59 (m), 2.23 (m), δC 30.1; δH 2.66 (m), 2.47 (m), δC 28.8; δH 2.52 (2H, m), δC 26.6], five methyl groups [δH 1.06 (3H, s), δC 25.4; δH 1.13 (3H, s), δC 21.6; δH 1.11 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), δC 20.8; δH 1.11 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), δC 20.6; δH 1.37 (3H, s), δC 14.9], two keto groups (δC 213.1, 195.9), and a lactone carbonyl group (δC 170.9). The NMR spectroscopic data indicated that 1 was a rearranged abietane.

The existence of an isopropyl group was suggested by 1H,1H-COSY correlations between H-15 and protons of two methyl groups [δH 1.11 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H)]. From 1H,1H-COSY correlations, three further proton–proton spin systems, viz. H2-1–H2-2, H2-11–H2-12, and H-5–H2-6, were deduced (Figure 2).

![[1860-5397-10-23-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-10-23-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Selected 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations for decandrinin (1).

Figure 2: Selected 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations for decandrinin (1).

HMBC correlations between H3-16/C-13, H3-17/C-13, and H-14/C-15 placed the above isopropyl group at C-13, while those from H-14 to C-9 and C-12 indicated the presence of a ∆13,14 double bond. HMBC correlations from H3-18, H3-19, and H2-2 to the carbon at δC 213.1 suggested the location of a keto group at C-3, whereas those from H2-11 to the carbon at δC 195.9 indicated that there was another keto group at C-8 (Figure 2).

HMBC correlations from H-5 and H2-6 to the carbonyl carbon (δC 170.9) of a δ-lactone suggested its location at C-7, while those from H2-11, H-14, and H3-20 to the quaternary carbon (δC 88.3) placed it at C-9 (Figure 2).

The NOE interactions for the two methyl groups at C-4 suggested that one methyl group is located at the same side as H-5, while the other one has the same orientation as Me-20. The NOEs between the two protons of the methylene at C-11 and Me-20 led to the conclusion that the carbonyl at C-8 is opposite to Me-20 (Figure 3). If the carbonyl at C-8 was oriented in the same direction as Me-20 these NOEs would not be observed because there would be several atoms between the concerned protons (Figure S9 in Supporting Information File 1). Therefore, the relative configuration of 1 was identified as shown in Figure 1.

![[1860-5397-10-23-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-10-23-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Diagnostic NOE interactions for decandrinin (1, B97D/TZVP-optimized structure): arbitrarily the 5R,9R,10S-enantiomer is shown.

Figure 3: Diagnostic NOE interactions for decandrinin (1, B97D/TZVP-optimized structure): arbitrarily the 5R,9...

The absolute configuration of 1 was assigned by CD and ORD spectroscopy in combination with quantum-chemical calculations. The conformational analysis of 1 by using RI-SCS-MP2/def2-TZVP//B97D/TZVP yielded six relevant conformers within the energetical range of 3 kcal/mol above the global minimum. For each of the six conformers thus identified, TDB2PLYP/def2-TZVP calculations were performed providing single UV and CD spectra, which were then summed up with Boltzmann weighting. The resulting averaged CD spectrum was corrected by a UV shift [26] of 13 nm and compared with the experimental CD curve (Figure 4). While the CD curve predicted for the 5R,9R,10S-configuration was nearly opposite to the one experimentally observed, the spectrum calculated for the 5S,9S,10R-enantiomer showed a good fitting with a moderate ΔESI value of 58% [27]. To further corroborate the assignment of the absolute configuration of 1, ORD calculations were performed using the PBE0/cc-pVDZ//B97D/TZVP method. The ORD calculated for the 5S,9S,10R-configuration in the non-resonant region matched with the one observed experimentally (Figure S10 in Supporting Information File 1). The good agreement of the experimental CD and ORD spectra with the ones calculated for the 5S,9S,10R-enantiomer revealed the absolute configuration of 1 to be as shown in Figure 4.

![[1860-5397-10-23-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-10-23-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Determination of the absolute configuration of decandrinin (1) by comparing the calculated CD spectra with the experimental one.

Figure 4: Determination of the absolute configuration of decandrinin (1) by comparing the calculated CD spect...

A plausible biogenetic precursor of decandrinin (1) might be the naturally more common β-diastereomer of 7,13-ent-abietadien-3-ol (2). Accordingly, its 3β-OH group would be oxidized to yield int A, whose C-9 would then be hydroxylated to afford int B. Oxidative cleavage at the ∆7,8 double bond of int B could yield int C. Finally, the lactonization of int C would give decandrinin (1) (Scheme 1).

![[1860-5397-10-23-i1]](/bjoc/content/inline/1860-5397-10-23-i1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Scheme 1: Proposed biosynthetic pathway for decandrinin (1).

Scheme 1: Proposed biosynthetic pathway for decandrinin (1).

Experimental

General methods

Optical rotation values were recorded on a JASCO P-1020 polarimeter. CD spectra were recorded on a J-715 spectropolarimeter (JASCO, Gross-Umstadt, Germany). UV spectra were obtained on a Beckman DU-640 UV spectrophotometer. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 NMR spectrometer in CDCl3. High-resolution ESI mass spectra were performed on a Bruker maXis UHR-TOF mass spectrometer in positive ion mode. For column chromatography, silica gel (200–300 mesh, Qingdao Mar. Chem. Ind. Co. Ltd.) and RP C18 gel (YMC) were used. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on a Shimadzu LC-6AD controller with an SPD-20A UV–vis detector equipped with YMC-Pack ODS-A columns (250 × 10 mm i.d., 5 μm and 250 × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 μm).

Plant material

As described previously [7] the bark of Ceriops decandra were collected in September 2009 in the estuary of Godavari, Andhra Pradesh, India. The identification of the plant was performed by one of the authors (T.S.). A voucher sample (No. CD-001) is maintained at the Marine Drugs Research Center, College of Pharmacy, Jinan University.

Extraction and isolation

The extraction and isolation procedures were in part identical to those described recently [7]: The chloroform extract (65.2 g) from air-dried bark (7.4 kg) of C. decandra was subjected to silica-gel column chromatography (200−300 mesh, 3.0 kg) and eluted with petroleum ether/acetone (100:0 to 1:2) to yield 285 fractions. Fractions 173 to 204 were combined and further purified using RP C18 column chromatography eluted with acetone/H2O (30:70 to 100:0) to give 57 subfractions. Subfractions 8–13 were combined and subjected to preparative HPLC (YMC-Pack 250 × 10 mm i.d., MeCN/H2O, 32:68) to afford eight subfractions. Then the sixth subfraction was further purified by HPLC (YMC-Pack 250 × 4.6 mm i.d., MeOH/H2O, 40:60) to provide 1 (1.9 mg).

Characterization

Decandrinin (1): Colorless solid; [α]D25 +242.0 (c 0.12, Me2CO); UV (MeCN) λmax 246.9 nm; For 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data (see Table 1); HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C20H29O4, 333.2060; found 333.2053.

Computational details

The B97D/TZVP [28,29] method was used to perform the conformational analysis of 1 with Gaussian 09 [30]. Single-point energy calculations at the RI-SCS-MP2/def2-TZVP [31,32] level and TDB2PLYP/def2-TZVP [33-35] calculations in combination with the COSMO solvation model with acetonitrile as a solvent and the chain-of-spheres approximations [35-37] were done using ORCA [38]. The optical rotatory dispersion (ORD) was calculated at the PBE0/cc-pVDZ [39,40] level using Gaussian 09. The Boltzmann weighting of single UV and CD spectra, UV shift, the determination of ΔESI values in the wavelength region between 190 nm and 380 nm (13 nm UV shift, σ = 0.22 eV), and the comparison of the calculated CD (σ = 0.22 eV) and ORD spectra with those observed experimentally were done with SpecDis 1.61 [41].

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: HRMS (ESI) and NMR spectra of decandrinin (1), NOE interactions for the B97D/TZVP-optimized structure diagnostic for the 9-epimer of decandrinin (1), and comparison of the calculated ORD with the experimental one. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.7 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by NSFC (31100258, 31170331, and 81125022), the Guangdong Key Science and Technology Special Project (2011A080403020), and the Special Financial Fund of Innovative Development of Marine Economic Demonstration Project (GD2012-D01-001). The authors thank Franziska Witterauf for the experimental CD and ORD measurements. F.Z.K. is grateful to the BEBUC Excellence Scholarship System and the Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung for the support of his master studies.

References

-

Wu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, M.-Y.; Pan, J.-Y.; Yang, M.-H. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 955–981. doi:10.1039/b807365a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, Y.; Tan, F.; Su, G.; Deng, S.; He, H.; Shi, S. Genetica 2008, 133, 47–56. doi:10.1007/s10709-007-9182-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheue, C.-R.; Liu, H.-Y.; Tsai, C.-C.; Rashid, S. M. A.; Yong, J. W. H.; Yang, Y.-P. Blumea 2009, 54, 220–227. doi:10.3767/000651909X476193

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheue, C.-R.; Liu, H.-Y.; Tsai, C.-C.; Yang, Y.-P. Bot. Stud. 2010, 51, 237–248.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rastogi, R. P.; Mehrotra, B. N. Compendium of Indian Plants; New Delhi, 1991.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H.; Li, M.-Y.; Wu, J. Chem. Biodiversity 2012, 9, 1–11. doi:10.1002/cbdv.201000299

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H.; Li, M.-Y.; Satyanandamurty, T.; Wu, J. Planta Med. 2013, 79, 666–672. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1328459

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2008, 35, 753–833. doi:10.1016/S1572-5995(08)80017-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Baxter, R. L.; Blake, A. J.; Gould, R. O. Phytochemistry 1995, 38, 195–197. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(94)00588-K

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1997, 14, 245–258. doi:10.1039/NP9971400245

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Siddiqui, B. S.; Perwaiz, S.; Begum, S. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 10087–10090. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.08.043

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2002, 19, 125–132. doi:10.1039/b009027l

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 1332–1341. doi:10.1039/b705951p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, W.-G.; Du, X.; Li, X.-N.; Yan, B.-C.; Zhou, M.; Wu, H.-Y.; Zhan, R.; Dong, K.; Pu, J.-X.; Sun, H.-D. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2013, 3, 145–149. doi:10.1007/s13659-013-0057-0

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Xu, X.-H.; Zhang, W.; Cao, X.-P.; Xue, S. Phytochem. Lett. 2011, 4, 52–55. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2010.12.003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 785–793. doi:10.1039/b414026p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kelecom, A.; Dos Santos, T. C.; Medeiros, W. L. B. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 2337–2340. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84714-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohtsu, H.; Iwamoto, M.; Ohishi, H.; Matsunaga, S.; Tanaka, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 6419–6422. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(99)01191-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Salae, A. W.; Rodjun, A.; Karalai, C.; Ponglimanont, C.; Chantrapromma, S.; Kanjana-Opas, A.; Tewtrakul, S.; Fun, H.-K. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 819–829. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.11.058

Return to citation in text: [1] -

da Cruz Araújo, E. C.; Lima, M. A. S.; Silveira, E. R. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2004, 42, 1049–1052. doi:10.1002/mrc.1489

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, N.-Y.; Tao, W.-W.; Duan, J.-A.; Tian, L.-J. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1528–1533. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.06.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, X.-W.; Feng, L.; Li, S.-M.; Liu, X.-H.; Li, Y.-L.; Wu, L.; Shen, Y.-H.; Tian, J.-M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.-R.; Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.-D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 744–754. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.055

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zheng, C.-J.; Huang, B.-K.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Han, T.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Qin, L.-P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 175–181. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chyu, C.-F.; Chiang, Y.-M.; Lin, H.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 641–643. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.07.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005, 22, 594–602. doi:10.1039/b501834j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bringmann, G.; Bruhn, T.; Maksimenka, K.; Hemberger, Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 2717–2727. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200801121

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bruhn, T.; Hemberger, Y.; Schaumlöffel, A.; Bringmann, G. Chirality 2013, 25, 243–249. doi:10.1002/chir.22138

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grimme, S. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. doi:10.1002/jcc.20495

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schäfer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. doi:10.1063/1.463096

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Caricato, M.; Li, X.; Hratchian, H. P.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Bloino, J.; Zheng, G.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Montgomery, J. A.; Peralta, J. E., Jr.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Keith, T.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Knox, J. E.; Cross, J. B.; Bakken, V.; Adamo, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Gomperts, R.; Stratmann, R. E.; Yazyev, O.; Austin, A. J.; Cammi, R.; Pomelli, C.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Voth, G. A.; Salvador, P.; Dannenberg, J. J.; Dapprich, S.; Daniels, A. D.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J. B.; Ortiz, J. V.; Cioslowski, J.; Fox D. J. in Gaussian 09, revision B.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2010.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 9095–9102. doi:10.1063/1.1569242

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. doi:10.1039/b508541a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 034108. doi:10.1063/1.2148954

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grimme, S.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 154116. doi:10.1063/1.2772854

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Petrenko, T.; Kossmann, S.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 054116. doi:10.1063/1.3533441

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Hansen, A.; Becker, U. Chem. Phys. 2009, 356, 98–109. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.10.036

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kossmann, S.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 2325–2338. doi:10.1021/ct100199k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Neese, F.; Becker, U.; Ganyushin, D.; Hansen, A.; Liakos, D.; Kollmar, C.; Koβmann, S.; Petrenko, T.; Reimann, C.; Riplinger, C.; Sivalingam, K.; Wezista, B.; Wennmohs, F. ORCA – an ab initio, density functional and semiempirical program package, version 2.9.1, Max Planck Institute for Bioinorganic Chemistry, Germany, 2012.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Adamo, C.; Barone, V. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. doi:10.1063/1.478522

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dunning, T. H., Jr. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. doi:10.1063/1.456153

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bruhn, T.; Schaumlöffel, A.; Hemberger, Y.; Bringmann, G. SpecDis, version 1.61, University of Würzburg, Germany, 2013.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Wu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, M.-Y.; Pan, J.-Y.; Yang, M.-H. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 955–981. doi:10.1039/b807365a |

| 2. | Huang, Y.; Tan, F.; Su, G.; Deng, S.; He, H.; Shi, S. Genetica 2008, 133, 47–56. doi:10.1007/s10709-007-9182-1 |

| 3. | Sheue, C.-R.; Liu, H.-Y.; Tsai, C.-C.; Rashid, S. M. A.; Yong, J. W. H.; Yang, Y.-P. Blumea 2009, 54, 220–227. doi:10.3767/000651909X476193 |

| 4. | Sheue, C.-R.; Liu, H.-Y.; Tsai, C.-C.; Yang, Y.-P. Bot. Stud. 2010, 51, 237–248. |

| 8. | Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2008, 35, 753–833. doi:10.1016/S1572-5995(08)80017-8 |

| 14. | Wang, W.-G.; Du, X.; Li, X.-N.; Yan, B.-C.; Zhou, M.; Wu, H.-Y.; Zhan, R.; Dong, K.; Pu, J.-X.; Sun, H.-D. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2013, 3, 145–149. doi:10.1007/s13659-013-0057-0 |

| 7. | Wang, H.; Li, M.-Y.; Satyanandamurty, T.; Wu, J. Planta Med. 2013, 79, 666–672. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1328459 |

| 26. | Bringmann, G.; Bruhn, T.; Maksimenka, K.; Hemberger, Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 2717–2727. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200801121 |

| 6. | Wang, H.; Li, M.-Y.; Wu, J. Chem. Biodiversity 2012, 9, 1–11. doi:10.1002/cbdv.201000299 |

| 22. | Yang, X.-W.; Feng, L.; Li, S.-M.; Liu, X.-H.; Li, Y.-L.; Wu, L.; Shen, Y.-H.; Tian, J.-M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.-R.; Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.-D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 744–754. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.055 |

| 23. | Zheng, C.-J.; Huang, B.-K.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Han, T.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Qin, L.-P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 175–181. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.004 |

| 24. | Chyu, C.-F.; Chiang, Y.-M.; Lin, H.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 641–643. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.07.008 |

| 25. | Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005, 22, 594–602. doi:10.1039/b501834j |

| 8. | Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2008, 35, 753–833. doi:10.1016/S1572-5995(08)80017-8 |

| 15. | Xu, X.-H.; Zhang, W.; Cao, X.-P.; Xue, S. Phytochem. Lett. 2011, 4, 52–55. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2010.12.003 |

| 16. | Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 785–793. doi:10.1039/b414026p |

| 8. | Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2008, 35, 753–833. doi:10.1016/S1572-5995(08)80017-8 |

| 20. | da Cruz Araújo, E. C.; Lima, M. A. S.; Silveira, E. R. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2004, 42, 1049–1052. doi:10.1002/mrc.1489 |

| 8. | Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2008, 35, 753–833. doi:10.1016/S1572-5995(08)80017-8 |

| 14. | Wang, W.-G.; Du, X.; Li, X.-N.; Yan, B.-C.; Zhou, M.; Wu, H.-Y.; Zhan, R.; Dong, K.; Pu, J.-X.; Sun, H.-D. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2013, 3, 145–149. doi:10.1007/s13659-013-0057-0 |

| 21. | Yang, N.-Y.; Tao, W.-W.; Duan, J.-A.; Tian, L.-J. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1528–1533. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.06.008 |

| 22. | Yang, X.-W.; Feng, L.; Li, S.-M.; Liu, X.-H.; Li, Y.-L.; Wu, L.; Shen, Y.-H.; Tian, J.-M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.-R.; Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.-D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 744–754. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.055 |

| 8. | Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2008, 35, 753–833. doi:10.1016/S1572-5995(08)80017-8 |

| 11. | Siddiqui, B. S.; Perwaiz, S.; Begum, S. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 10087–10090. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.08.043 |

| 12. | Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2002, 19, 125–132. doi:10.1039/b009027l |

| 13. | Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 1332–1341. doi:10.1039/b705951p |

| 9. | Baxter, R. L.; Blake, A. J.; Gould, R. O. Phytochemistry 1995, 38, 195–197. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(94)00588-K |

| 10. | Hanson, J. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1997, 14, 245–258. doi:10.1039/NP9971400245 |

| 8. | Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2008, 35, 753–833. doi:10.1016/S1572-5995(08)80017-8 |

| 17. | Kelecom, A.; Dos Santos, T. C.; Medeiros, W. L. B. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 2337–2340. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84714-7 |

| 18. | Ohtsu, H.; Iwamoto, M.; Ohishi, H.; Matsunaga, S.; Tanaka, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 6419–6422. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(99)01191-0 |

| 19. | Salae, A. W.; Rodjun, A.; Karalai, C.; Ponglimanont, C.; Chantrapromma, S.; Kanjana-Opas, A.; Tewtrakul, S.; Fun, H.-K. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 819–829. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.11.058 |

| 7. | Wang, H.; Li, M.-Y.; Satyanandamurty, T.; Wu, J. Planta Med. 2013, 79, 666–672. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1328459 |

| 27. | Bruhn, T.; Hemberger, Y.; Schaumlöffel, A.; Bringmann, G. Chirality 2013, 25, 243–249. doi:10.1002/chir.22138 |

| 7. | Wang, H.; Li, M.-Y.; Satyanandamurty, T.; Wu, J. Planta Med. 2013, 79, 666–672. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1328459 |

| 39. | Adamo, C.; Barone, V. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. doi:10.1063/1.478522 |

| 40. | Dunning, T. H., Jr. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. doi:10.1063/1.456153 |

| 41. | Bruhn, T.; Schaumlöffel, A.; Hemberger, Y.; Bringmann, G. SpecDis, version 1.61, University of Würzburg, Germany, 2013. |

| 35. | Petrenko, T.; Kossmann, S.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 054116. doi:10.1063/1.3533441 |

| 36. | Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Hansen, A.; Becker, U. Chem. Phys. 2009, 356, 98–109. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.10.036 |

| 37. | Kossmann, S.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 2325–2338. doi:10.1021/ct100199k |

| 38. | Neese, F.; Becker, U.; Ganyushin, D.; Hansen, A.; Liakos, D.; Kollmar, C.; Koβmann, S.; Petrenko, T.; Reimann, C.; Riplinger, C.; Sivalingam, K.; Wezista, B.; Wennmohs, F. ORCA – an ab initio, density functional and semiempirical program package, version 2.9.1, Max Planck Institute for Bioinorganic Chemistry, Germany, 2012. |

| 31. | Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 9095–9102. doi:10.1063/1.1569242 |

| 32. | Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. doi:10.1039/b508541a |

| 33. | Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 034108. doi:10.1063/1.2148954 |

| 34. | Grimme, S.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 154116. doi:10.1063/1.2772854 |

| 35. | Petrenko, T.; Kossmann, S.; Neese, F. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 054116. doi:10.1063/1.3533441 |

| 28. | Grimme, S. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. doi:10.1002/jcc.20495 |

| 29. | Schäfer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. doi:10.1063/1.463096 |

| 30. | Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Caricato, M.; Li, X.; Hratchian, H. P.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Bloino, J.; Zheng, G.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Montgomery, J. A.; Peralta, J. E., Jr.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Keith, T.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Knox, J. E.; Cross, J. B.; Bakken, V.; Adamo, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Gomperts, R.; Stratmann, R. E.; Yazyev, O.; Austin, A. J.; Cammi, R.; Pomelli, C.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Voth, G. A.; Salvador, P.; Dannenberg, J. J.; Dapprich, S.; Daniels, A. D.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J. B.; Ortiz, J. V.; Cioslowski, J.; Fox D. J. in Gaussian 09, revision B.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2010. |

© 2014 Wang et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)

![[1860-5397-10-23-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-10-23-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)