Abstract

Background

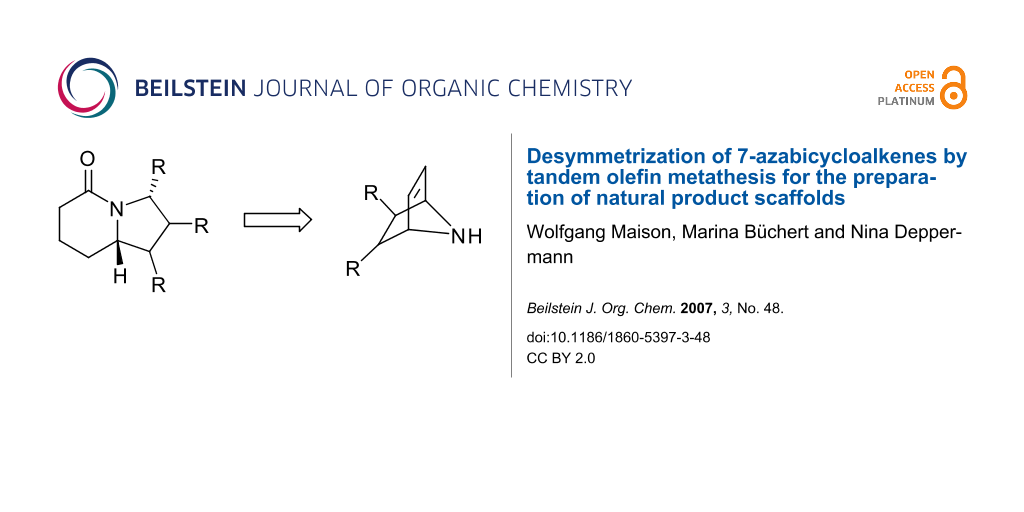

Tandem olefin metathesis sequences are known to be versatile for the generation of natural product scaffolds and have also been used for ring opening of strained carbo- and heterocycles. In this paper we demonstrate the potential of these reactions for the desymmetrization of 7-azabicycloalkenes.

Results

We have established efficient protocols for the desymmetrization of different 7-azabicycloalkenes by intra- and intermolecular tandem metathesis sequences with ruthenium based catalysts.

Conclusion

Desymmetrization of 7-azabicycloalkenes by olefin metathesis is an efficient process for the preparation of common natural product scaffolds such as pyrrolidines, indolizidines and isoindoles.

Graphical Abstract

Background

Azabicyclo [x.y.0]alkane scaffolds are ubiquitous structural elements in pharmaceutically important peptide mimetics [1-3] and several important classes of natural products such as indolizidine and quinolizidine alkaloids and azasugars. [4-6] In consequence, a number of groups have developed efficient syntheses of these bicyclic heterocycles. [7-9] Challenges for the synthesis of these structures are the introduction of chirality and of several functional groups into the scaffolds. In particular the latter point is often a problem, leading to multistep sequences.

In this context, ring closing metathesis (RCM) and tandem metatheses [10-13] have been particularly successful strategies for the assembly of common natural product scaffolds. [14-22] A general advantage of these approaches is that ring closure and/or scaffold-rearrangements can be accomplished while generating a double bond as a valuable functional group for further manipulations. In addition, the common ruthenium (Figure 1) and molybdenum based catalysts for olefin metathesis are well known for their broad functional group tolerance.

Figure 1: Ruthenium based precatalysts used in this study.

Figure 1: Ruthenium based precatalysts used in this study.

The application of RCM to the synthesis of azabicycloalkane scaffolds was first described by Grubbs[23] for the synthesis of peptide mimetics and later extended by several other groups. [24-31] Key intermediates in these approaches are often alkenyl substituted pyrrolidines, which are N-acylated with an unsaturated carboxylic acid and submitted to a ring closing metathesis (RCM).

As a part of a general synthetic concept using azabicycloalkenes as masked analogs of functionalized pyrrolidines or piperidines [32-39] we have previously applied the concept of intramolecular ring-opening/ring-closing metathesis (RORCM) [40-54] to N-acylated 2-azabicycloalkenes 4 as precursors for azabicyclo [X.3.0]alkanes like 6 (Scheme 1).[55] Various other strained heterocycles have also been used for ring opening metathesis or other tandem metathesis sequences. [56-61]

Scheme 1: RORCM of 2-azabicycloalkenes 5 to bicyclic scaffolds 6.

Scheme 1: RORCM of 2-azabicycloalkenes 5 to bicyclic scaffolds 6.

In this paper, we describe the extension of this work and show that desymmetrization of 7-azabicycloalkenes via RORCM leads to valuable natural product scaffolds. In this context, symmetrical derivatives of 7-azabicycloalkenes like 7 and 12 are extremely interesting substrates for RORCM conversions, because they may be desymmetrized either by diastereoselective or enantioselective metathesis.

Results and Discussion

In a first attempt to transfer the RORCM-strategy to 7-azabicycloalkenes, we chose 7 as a precursor for domino metathesis reactions. Our choice was due to the following two reasons: 1. Azabicycloalkene 7 is easy to synthesize via Diels-Alder reaction.[62] 2. It was assumed to be a good substrate for RORCM because it is strained and has been shown to be susceptible to other desymmetrizing ring opening reactions in the past.[63,64]

To generate appropriate precursors for the tandem conversions, 7 was deprotected and acylated with butenoic acid and pentenoyl chloride to give 8 and 10. However, first attempts to convert the bis-olefin 8 via RORCM to the bicyclic target structure failed and only pyridone derivative 9 was isolated in small quantities along with large amounts of unreacted starting material. With turnover numbers of only three, the ruthenium based catalysts 1 and 2 were both quite ineffective in this metathesis reaction.

We assumed that the structure of the starting material 8 (location of the exocyclic double bond) and the following aromatization to 9 was the reason for the low catalytic efficiency of this conversion and tested this hypothesis with the conversion of the corresponding pentenoyl derivative 10 under RORCM conditions. As outline in Scheme 2, this reaction gave the expected metathesis product, which was hydrogenated to the isoindole derivative 11 in good yield, verifying our previous assumptions.

Scheme 2: RORCM of 7-azabicycloalkenes 8 and 10 to pyridone 9 and isoindole scaffold 11.

Scheme 2: RORCM of 7-azabicycloalkenes 8 and 10 to pyridone 9 and isoindole scaffold 11.

As a general trend, it turned out that benzannelated azabicycloalkene derivatives like 8 and 10 give relatively unstable products. In consequence, products can only be isolated as pyridones 9, derived from spontaneous aromatization or have to be hydrogenated to their saturated analogues 11.

This unique reactivity of benzannelated metathesis precursors like 8 and 10 is not observed with other 7-azabicycloalkenes like 13 and 16 as depicted in Scheme 3. Starting from the known Boc-protected heterocycle 12,[65,66] RORCM precursors 13 and 16 were generated after deprotection under standard acylation conditions in good yields. Treatment of these bis-olefins with Grubbs catalyst 1 gave the expected bicyclic compounds 14 and 17 in good yield along with some byproducts 15 and 18, respectively. These byproducts are often observed, if the generated exocyclic double bond in the RORCM product is susceptible to olefin cross metathesis with the small amount of styrene that is derived from the precatalyst 1. These types of products are favored, if additional olefins are added as CM partners. With addition of 3 equivalents styrene (condition A in Scheme 3), for example, the styrene adduct 15 becomes the main product.

Scheme 3: RORCM of 7-azabicycloalkenes 13 and 16 to bicyclic scaffolds 14, 15, 17 and 18. Conditions A: 10 mol % 1, C2H4, 3 equiv styrene, CH2Cl2, rt, 12 h; B: 10 mol % 1, C2H4, CH2Cl2, rt, 12 h.

Scheme 3: RORCM of 7-azabicycloalkenes 13 and 16 to bicyclic scaffolds 14, 15, 17 and 18. Conditions A: 10 mo...

Having established suitable protocols for conversions of 7-azabicycloalkenes to racemic products, we tried next to develop stereoselective variants and started our studies again with Boc-protected 7-azabicycloalkenes 7 and 12. A sequence of ring opening and cross metathesis is extremely efficient for desymmetrization of 7 and 12 as depicted in Scheme 4 for the synthesis of isoindole 19 and the disubstituted pyrrolidine 20. In these cases, catalyst loadings can be low and yields are excellent.

Scheme 4: ROCM of 7-azabicycloalkenes 7 and 12 to isoindole and pyrrolidine scaffolds 19 and 20.

Scheme 4: ROCM of 7-azabicycloalkenes 7 and 12 to isoindole and pyrrolidine scaffolds 19 and 20.

Unfortunately the ROCM of 7-azabicycloalkenes appeared to be quite sensitive with respect to the olefin cross metathesis partner [67] and we have not been able to transfer this reaction to α-substituted olefins like 21 yet.

A more successful attempt to introduce selectivity, was the enantioselective catalytic desymmetrization of bis-olefin 10 with the known chiral ruthenium catalyst 3.[67] This reaction gave enantioenriched 11 in good yield (Scheme 5). However, the enantioselectivity of this reaction is only moderate compared to similar reactions using molybdenum based precatalysts and different azabicycloalkene starting materials that have been recently reported by Hoveyda and Schrock for the enantioselective preparation of piperidines.[68,69]

Scheme 5: Catalytic enantioselective desymmetrization of 7-azabicycloalkene 10 to scaffold 23.

Scheme 5: Catalytic enantioselective desymmetrization of 7-azabicycloalkene 10 to scaffold 23.

Conclusion

In this paper we have described efficient tandem metathesis protocols for the desymmetrization of 7-azabicycloalkenes. Desymmetrization is accomplished by intramolecular RORCM or intermolecular ROCM sequences to give a range of common natural product scaffolds such as pyrrolidines, indolizidines and isoindoles. The protocols use readily available starting materials, are simple and give densely functionalized metathesis products ready for further manipulations.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental. Experimental procedures for the synthesis of all compounds described, and characterization data for the synthesized compounds. | ||

| Format: DOC | Size: 60.5 KB | Download |

References

-

Cluzeau, J.; Lubell, W. D. Biopolymers 2005, 80, 98–150. doi:10.1002/bip.20213

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Belvisi, L.; Colombo, L.; Manzoni, L.; Potenza, D.; Scolastico, C. Synlett 2004, 1449–1471. doi:10.1055/s-2004-829540

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suat Kee, K.; Jois, S. D. S. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003, 9, 1209–1224. doi:10.2174/1381612033454900

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Michael, J. P. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 191–222. doi:10.1039/b509525p

and previous articles of this series.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Felpin, F. X.; Lebreton, J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 3693–3712. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200300193

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoda, H. Curr. Org. Chem. 2002, 6, 223–243. doi:10.2174/1385272024605069

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maison, W.; Prenzel, A. H. G. P. Synthesis 2005, 1031–1049. doi:10.1055/s-2005-865295

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Enders, D.; Thiebes, T. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 573–578. doi:10.1351/pac200173030573

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hanessian, S.; McNaughton-Smith, G.; Lombart, H. G.; Lubell, W. D. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 12789–12854. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00298-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Astruc, D. New J. Chem. 2005, 29, 42–56. doi:10.1039/b412198h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grubbs, R. H. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 7117–7140. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.05.124

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schrock, R. R.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 4592–4633. doi:10.1002/anie.200300576

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fuerstner, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3012–3043. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20000901)39:17<3012::AID-ANIE3012>3.0.CO;2-G

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Martin, W. H. C.; Blechert, S. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 1521–1540. doi:10.2174/156802605775009757

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nakamura, I.; Yamamoto, Y. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2127–2198. doi:10.1021/cr020095i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deiters, A.; Martin, S. F. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2199–2238. doi:10.1021/cr0200872

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Larry, Y. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2963–3008. doi:10.1021/cr990407q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Phillips, A. J.; Abell, A. D. Aldrichimica Acta 1999, 32, 75–89.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fuerstner, A. Top. Organomet. Chem. 1998, 1, 37–72.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Armstrong, S. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 371–388. doi:10.1039/a703881j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grubbs, R. H. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 4413–4450. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)10427-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schuster, M.; Blechert, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 2037–2056. doi:10.1002/anie.199720361

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Miller, S. J.; Grubbs, R. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5855–5856. doi:10.1021/ja00126a027

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manzoni, L.; Colombo, M.; Scolastico, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 2623–2625. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.01.126

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krelaus, R.; Westermann, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 5987–5990. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.06.052

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harris, P. W. R.; Brimble, M. A.; Gluckman, P. D. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1847–1850. doi:10.1021/ol034370e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hoffmann, T.; Lanig, H.; Waibel, R.; Gmeiner, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3361–3364. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010917)40:18<3361::AID-ANIE3361>3.0.CO;2-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lim, S. H.; Ma, S.; Beak, P. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 9056–9062. doi:10.1021/jo0108865

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Beal, L. M.; Liu, B.; Chu, W.; Moeller, K. D. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 10113–10125. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00856-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grossmith, C. E.; Senia, F.; Wagner, J. Synlett 1999, 1660–1662. doi:10.1055/s-1999-2887

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Beal, L. M.; Moeller, K. D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 4639–4642. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00858-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grohs, D. C.; Maison, W. Amino Acids 2005, 29, 131–138. doi:10.1007/s00726-005-0182-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grohs, D. C.; Maison, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 4373–4376. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.04.082

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maison, W.; Grohs, D. C.; Prenzel, A. H. G. P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 1527–1543. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200300700

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arakawa, Y.; Ohnishi, M.; Yoshimura, N.; Yoshifuji, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 1015–1020. doi:10.1248/cpb.51.1015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arakawa, Y.; Murakami, T.; Yoshifuji, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 96–97. doi:10.1248/cpb.51.96

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arakawa, Y.; Murakami, T.; Ozawa, F.; Arakawa, Y.; Yoshifuji, S. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7555–7563. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(03)01200-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maison, W.; Küntzer, D.; Grohs, D. C. Synlett 2002, 1795–1798. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34901

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jaeger, M.; Polborn, K.; Steglich, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 861–864. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(94)02432-B

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hart, A. C.; Phillips, A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1094–1095. doi:10.1021/ja057899a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Funel, J. A.; Prunet, J. Synlett 2005, 235–238. doi:10.1055/s-2004-837200

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takao, K. I.; Yasui, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Sasaki, D.; Kawasaki, S.; Watanabe, G.; Tadano, K. I. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 8789–8795. doi:10.1021/jo048566j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lesma, G.; Crippa, S.; Danieli, B.; Sacchetti, A.; Silvani, A.; Virdis, A. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 6437–6442. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.06.051

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Holtsclaw, J.; Koreeda, M. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 3719–3722. doi:10.1021/ol048650l

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schaudt, M.; Blechert, S. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 2913–2920. doi:10.1021/jo026803h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wrobleski, A.; Sahasrabudhe, K.; Aubé, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9974–9975. doi:10.1021/ja027113y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hagiwara, H.; Katsumi, T.; Endou, S.; Hoshi, T.; Suzuki, T. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 6651–6654. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00690-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Banti, D.; North, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 1561–1564. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00009-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Minger, T. L.; Phillips, A. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 5357–5359. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00905-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Limanto, J.; Snapper, M. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8071–8072. doi:10.1021/ja001946b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Adams, J. A.; Ford, J. G.; Stamatos, P. J.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 9690–9696. doi:10.1021/jo991323k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stragies, R.; Blechert, S. Synlett 1998, 169–170. doi:10.1055/s-1998-1592

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burke, S. D.; Quinn, K. J.; Chen, V. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 8626–8627. doi:10.1021/jo981342e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stille, J. R.; Santarsiero, B. D.; Grubbs, R. H. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 843–862. doi:10.1021/jo00290a013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Büchert, M.; Meinke, S.; Prenzel, A. H. G. P.; Deppermann, N.; Maison, W. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5553–5556. doi:10.1021/ol062219+

For a parallel study in the Blechert group see: N. Rodriguez y Fischer, Ringumlagerungsmetathesen zu Azacyclen, Dissertation, TU Berlin, 2004.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dunne, A. M.; Mix, S.; Blechert, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 2733–2736. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(03)00346-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arjona, O.; Csáky, A. G.; Medel, R.; Plumet, J. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 1380–1383. doi:10.1021/jo016000e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ishikura, M.; Saijo, M.; Hino, A. Heterocycles 2003, 59, 573–585.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arjona, O.; Csák, A. G.; Plumet, J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 611–622. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200390100

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, Z.; Rainier, J. D. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 459–462. doi:10.1021/ol052741g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, Z.; Rainier, J. D. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 131–133. doi:10.1021/ol047808z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lautens, M.; Fagnou, K.; Zunic, V. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 3465–3468. doi:10.1021/ol026579i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cho, Y. H.; Zunic, V.; Senboku, H.; Olsen, M.; Lautens, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6837–6846. doi:10.1021/ja0577701

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Namyslo, J. C.; Kaufmann, D. E. Synlett 1999, 804–806. doi:10.1055/s-1999-2719

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liang, F.; Navarro, H. A.; Abraham, P.; Kotian, P.; Ding, Y. S.; Fowler, J.; Volkow, N.; Kuhar, M. J.; Carroll, F. I. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 2293–2295. doi:10.1021/jm970187d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chatterjee, A. K.; Choi, T. L.; Sanders, D. P.; Grubbs, R. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11360–11370. doi:10.1021/ja0214882

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seiders, T. J.; Ward, D. W.; Grubbs, R. H. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 3225–3228. doi:10.1021/ol0165692

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cortez, G. A.; Baxter, C. A.; Schrock, R. R.; Hoveyda, A. H. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2871–2874. doi:10.1021/ol071008h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cortez, G. A.; Schrock, R. R.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4534–4538. doi:10.1002/anie.200605130

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 68. | Cortez, G. A.; Baxter, C. A.; Schrock, R. R.; Hoveyda, A. H. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2871–2874. doi:10.1021/ol071008h |

| 69. | Cortez, G. A.; Schrock, R. R.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4534–4538. doi:10.1002/anie.200605130 |

| 1. | Cluzeau, J.; Lubell, W. D. Biopolymers 2005, 80, 98–150. doi:10.1002/bip.20213 |

| 2. | Belvisi, L.; Colombo, L.; Manzoni, L.; Potenza, D.; Scolastico, C. Synlett 2004, 1449–1471. doi:10.1055/s-2004-829540 |

| 3. | Suat Kee, K.; Jois, S. D. S. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003, 9, 1209–1224. doi:10.2174/1381612033454900 |

| 14. | Martin, W. H. C.; Blechert, S. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 1521–1540. doi:10.2174/156802605775009757 |

| 15. | Nakamura, I.; Yamamoto, Y. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2127–2198. doi:10.1021/cr020095i |

| 16. | Deiters, A.; Martin, S. F. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2199–2238. doi:10.1021/cr0200872 |

| 17. | Larry, Y. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2963–3008. doi:10.1021/cr990407q |

| 18. | Phillips, A. J.; Abell, A. D. Aldrichimica Acta 1999, 32, 75–89. |

| 19. | Fuerstner, A. Top. Organomet. Chem. 1998, 1, 37–72. |

| 20. | Armstrong, S. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 371–388. doi:10.1039/a703881j |

| 21. | Grubbs, R. H. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 4413–4450. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)10427-6 |

| 22. | Schuster, M.; Blechert, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 2037–2056. doi:10.1002/anie.199720361 |

| 67. | Seiders, T. J.; Ward, D. W.; Grubbs, R. H. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 3225–3228. doi:10.1021/ol0165692 |

| 10. | Astruc, D. New J. Chem. 2005, 29, 42–56. doi:10.1039/b412198h |

| 11. | Grubbs, R. H. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 7117–7140. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.05.124 |

| 12. | Schrock, R. R.; Hoveyda, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 4592–4633. doi:10.1002/anie.200300576 |

| 13. | Fuerstner, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3012–3043. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20000901)39:17<3012::AID-ANIE3012>3.0.CO;2-G |

| 67. | Seiders, T. J.; Ward, D. W.; Grubbs, R. H. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 3225–3228. doi:10.1021/ol0165692 |

| 7. | Maison, W.; Prenzel, A. H. G. P. Synthesis 2005, 1031–1049. doi:10.1055/s-2005-865295 |

| 8. | Enders, D.; Thiebes, T. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 573–578. doi:10.1351/pac200173030573 |

| 9. | Hanessian, S.; McNaughton-Smith, G.; Lombart, H. G.; Lubell, W. D. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 12789–12854. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00298-6 |

| 63. |

Cho, Y. H.; Zunic, V.; Senboku, H.; Olsen, M.; Lautens, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6837–6846. doi:10.1021/ja0577701

and references cited therein. |

| 64. | Namyslo, J. C.; Kaufmann, D. E. Synlett 1999, 804–806. doi:10.1055/s-1999-2719 |

| 4. |

Michael, J. P. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 191–222. doi:10.1039/b509525p

and previous articles of this series. |

| 5. | Felpin, F. X.; Lebreton, J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 3693–3712. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200300193 |

| 6. | Yoda, H. Curr. Org. Chem. 2002, 6, 223–243. doi:10.2174/1385272024605069 |

| 65. | Liang, F.; Navarro, H. A.; Abraham, P.; Kotian, P.; Ding, Y. S.; Fowler, J.; Volkow, N.; Kuhar, M. J.; Carroll, F. I. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 2293–2295. doi:10.1021/jm970187d |

| 66. | Chatterjee, A. K.; Choi, T. L.; Sanders, D. P.; Grubbs, R. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11360–11370. doi:10.1021/ja0214882 |

| 40. | Hart, A. C.; Phillips, A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1094–1095. doi:10.1021/ja057899a |

| 41. | Funel, J. A.; Prunet, J. Synlett 2005, 235–238. doi:10.1055/s-2004-837200 |

| 42. | Takao, K. I.; Yasui, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Sasaki, D.; Kawasaki, S.; Watanabe, G.; Tadano, K. I. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 8789–8795. doi:10.1021/jo048566j |

| 43. | Lesma, G.; Crippa, S.; Danieli, B.; Sacchetti, A.; Silvani, A.; Virdis, A. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 6437–6442. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.06.051 |

| 44. | Holtsclaw, J.; Koreeda, M. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 3719–3722. doi:10.1021/ol048650l |

| 45. | Schaudt, M.; Blechert, S. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 2913–2920. doi:10.1021/jo026803h |

| 46. | Wrobleski, A.; Sahasrabudhe, K.; Aubé, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9974–9975. doi:10.1021/ja027113y |

| 47. | Hagiwara, H.; Katsumi, T.; Endou, S.; Hoshi, T.; Suzuki, T. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 6651–6654. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00690-7 |

| 48. | Banti, D.; North, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 1561–1564. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00009-6 |

| 49. | Minger, T. L.; Phillips, A. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 5357–5359. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00905-X |

| 50. | Limanto, J.; Snapper, M. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8071–8072. doi:10.1021/ja001946b |

| 51. | Adams, J. A.; Ford, J. G.; Stamatos, P. J.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 9690–9696. doi:10.1021/jo991323k |

| 52. | Stragies, R.; Blechert, S. Synlett 1998, 169–170. doi:10.1055/s-1998-1592 |

| 53. | Burke, S. D.; Quinn, K. J.; Chen, V. J. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 8626–8627. doi:10.1021/jo981342e |

| 54. | Stille, J. R.; Santarsiero, B. D.; Grubbs, R. H. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 843–862. doi:10.1021/jo00290a013 |

| 56. | Dunne, A. M.; Mix, S.; Blechert, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 2733–2736. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(03)00346-0 |

| 57. | Arjona, O.; Csáky, A. G.; Medel, R.; Plumet, J. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 1380–1383. doi:10.1021/jo016000e |

| 58. | Ishikura, M.; Saijo, M.; Hino, A. Heterocycles 2003, 59, 573–585. |

| 59. | Arjona, O.; Csák, A. G.; Plumet, J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 611–622. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200390100 |

| 60. | Liu, Z.; Rainier, J. D. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 459–462. doi:10.1021/ol052741g |

| 61. | Liu, Z.; Rainier, J. D. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 131–133. doi:10.1021/ol047808z |

| 32. | Grohs, D. C.; Maison, W. Amino Acids 2005, 29, 131–138. doi:10.1007/s00726-005-0182-0 |

| 33. | Grohs, D. C.; Maison, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 4373–4376. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.04.082 |

| 34. | Maison, W.; Grohs, D. C.; Prenzel, A. H. G. P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 1527–1543. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200300700 |

| 35. | Arakawa, Y.; Ohnishi, M.; Yoshimura, N.; Yoshifuji, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 1015–1020. doi:10.1248/cpb.51.1015 |

| 36. | Arakawa, Y.; Murakami, T.; Yoshifuji, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 96–97. doi:10.1248/cpb.51.96 |

| 37. | Arakawa, Y.; Murakami, T.; Ozawa, F.; Arakawa, Y.; Yoshifuji, S. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7555–7563. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(03)01200-6 |

| 38. | Maison, W.; Küntzer, D.; Grohs, D. C. Synlett 2002, 1795–1798. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34901 |

| 39. | Jaeger, M.; Polborn, K.; Steglich, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 861–864. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(94)02432-B |

| 62. | Lautens, M.; Fagnou, K.; Zunic, V. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 3465–3468. doi:10.1021/ol026579i |

| 24. | Manzoni, L.; Colombo, M.; Scolastico, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 2623–2625. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.01.126 |

| 25. | Krelaus, R.; Westermann, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 5987–5990. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.06.052 |

| 26. | Harris, P. W. R.; Brimble, M. A.; Gluckman, P. D. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1847–1850. doi:10.1021/ol034370e |

| 27. | Hoffmann, T.; Lanig, H.; Waibel, R.; Gmeiner, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3361–3364. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010917)40:18<3361::AID-ANIE3361>3.0.CO;2-9 |

| 28. | Lim, S. H.; Ma, S.; Beak, P. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 9056–9062. doi:10.1021/jo0108865 |

| 29. | Beal, L. M.; Liu, B.; Chu, W.; Moeller, K. D. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 10113–10125. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00856-5 |

| 30. | Grossmith, C. E.; Senia, F.; Wagner, J. Synlett 1999, 1660–1662. doi:10.1055/s-1999-2887 |

| 31. | Beal, L. M.; Moeller, K. D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 4639–4642. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00858-2 |

| 23. | Miller, S. J.; Grubbs, R. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5855–5856. doi:10.1021/ja00126a027 |

| 55. |

Büchert, M.; Meinke, S.; Prenzel, A. H. G. P.; Deppermann, N.; Maison, W. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5553–5556. doi:10.1021/ol062219+

For a parallel study in the Blechert group see: N. Rodriguez y Fischer, Ringumlagerungsmetathesen zu Azacyclen, Dissertation, TU Berlin, 2004. |

© 2007 Maison et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)