Abstract

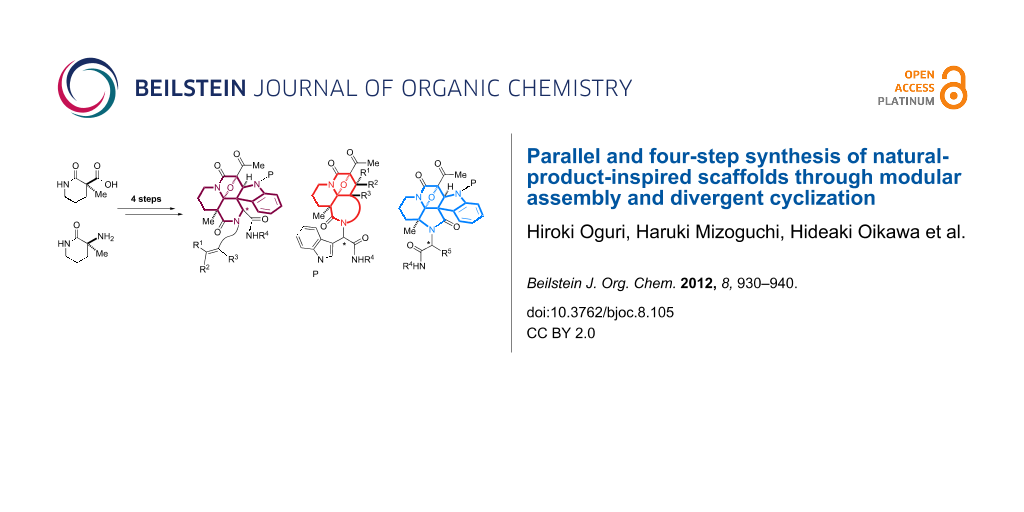

By emulating the universal biosynthetic strategy, which employs modular assembly and divergent cyclizations, we have developed a four-step synthetic process to yield a collection of natural-product-inspired scaffolds. Modular assembly of building blocks onto a piperidine-based manifold 6, having a carboxylic acid group, was achieved through Ugi condensation, N-acetoacetylation and diazotransfer, leading to cyclization precursors. The rhodium-catalyzed tandem cyclization and divergent cycloaddition gave rise to tetracyclic and hexacyclic scaffolds by the appropriate choice of dipolarophiles installed at modules 3 and 4. A different piperidine-based manifold 15 bearing an amino group was successfully applied to demonstrate the flexibility and scope of the unified four-step process for the generation of structural diversity in the fused scaffolds. Evaluation of in vitro antitrypanosomal activities of the collections and preliminary structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies were also undertaken.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Biologically intriguing natural products often possess cyclic scaffolds bearing dense arrays of functional groups and hydrogen-bond donors or acceptors. The incorporation of multiple sp3-centers on the scaffold creates a unique three-dimensional shape of the surface, which is responsible for specific molecular recognition with biomacromolecules in the cellular context [1-3]. To generate diverse collections of the elaborated cyclic scaffolds, nature has evolved biosynthetic machinery and often employs (1) modular assembly and (2) divergent cyclization [4]. As the simplest example of this structural diversification, the biosynthesis of aromatic polyketides is outlined in Figure 1a. Employing acetyl CoA as a starter unit, modular and iterative assembly of malonate extender units produces a linear tetraketide intermediate capable of being folded in at least two ways [5]. Intramolecular Claisen condensation and subsequent enolization produce phloracetophenone (path A), while aldol condensation followed by enolization and hydrolysis of the thioester yield orsellinic acid (path B). Inspired by this simple yet universal biosynthetic strategy, which generates structural variation among natural products, we envisioned the construction of chemical libraries featuring modular assembly for the rapid connection of simple building blocks, as well as divergent cyclization of a common precursor leading to distinct skeletons with complex molecular architectures.

Figure 1: (a) Biosynthetic outline of aromatic polyketides; (b) structure of indole alkaloids composed of indole (red) and piperidine (blue) groups; (c) divergent cyclizations to generate scaffold variations as an illustration of the “Build-Couple-Pair” strategy in diversity-oriented synthesis.

Figure 1: (a) Biosynthetic outline of aromatic polyketides; (b) structure of indole alkaloids composed of ind...

Since the naturally occurring indole alkaloids share indole and piperidine as common substructures (Figure 1b) [6], we conceived the assembly of the substructures and subsequent intramolecular cyclization between these substructures to form the fused skeletons (Figure 1c). As a pioneering approach to shape the foundation of the “Build-Couple-Pair” (B/C/P) strategy [7-15] for diversity-oriented synthesis [16,17], a synthetic process to access indole-alkaloid-like scaffolds utilizing a piperidine-based manifold 1, was developed in 2005 [18]. By exploiting lactam, carboxylic acid and β-ketocarbonyl functional groups on 1, α-diazoketocarbonyl and indole groups were installed to produce a set of tetraketide-like precursors, 2 and 3. Rhodium(II)-catalyzed tandem cyclization–cycloaddition [19-21] of the tetraketide-like precursors produced distinct multicyclic scaffolds, 4 and 5, differing in the relative orientations of the substructures. This approach illustrates a systematic way of diversifying skeletal arrays in a controlled manner.

With the intention to produce screening collections, we then devised a second-generation strategy applicable for a parallel synthetic protocol. This approach allows unified four-step access to a series of indole-alkaloid-like scaffolds. Some of these results were previously reported as a preliminary communication in 2009 [22]. As shown in Figure 2a, we conceived the modular assembly of three building blocks onto the piperidine-based manifold 6 with a carboxylic acid group. Ugi condensation [23-25] of 6 with indole-3-carbaldehyde 7, isonitrile and amine building blocks 8 and 9, followed by reaction with an acetylketene [26] would produce a tetraketide-like precursor 10 composed of five modules. Since two methylene groups in module 2 in the tetraketide-like moiety 10 are masked as an imide group and a quaternary center, respectively, the remaining methylene in module 1 would be regiospecifically manipulated through diazotransfer to form diazoimide 11 [27]. Rhodium(II)-catalyzed cyclization of 11 between modules 1 and 2 could generate a carbonium ylide intermediate 12. In this system, there is a dynamic conformational equilibrium of the tertiary amide, which is expected to allow divergent cycloadditions with the dipolarophiles installed at modules 3 and 4 leading to either tetracyclic 14 or hexacyclic 13. In this full account, we also employ a piperidine-based manifold 15 bearing an amino group in order to expand the applicability of the various building blocks in the four-step parallel synthesis. The modular assembly of 15 with 16, 17 and 8 based on Ugi condensation could produce a different dipeptidyl array of the precursor 18, which is expected to produce the distinct scaffold 19 compared to those produced from manifold 6. According to this strategy employing rhodium(II)-catalyzed tandem reactions, four sp2-centers were efficiently converted into the corresponding sp3-centers, including an aminoacetal core. In nature, there are a variety of alkaloids that possess an aminoacetal group (Figure 2b). The aminoacetal groups embedded in the skeleton are prone to undergo C–O bond cleavage to form electrophilic iminium species, which allow covalent bond formation with biomacromolecules (nucleic acids, proteins) in a cellular environment, and thereby play pivotal roles in defining their biological activities [28,29]. As a mechanistic rationale for the antitumor activities of quinocarcins, DNA alkylation exploiting the iminium moiety was proposed as shown in Figure 2b [30].

Figure 2: (a) Synthetic plans based on modular assembly and divergent cyclizations leading to fused skeletons; (b) structures of naturally occurring alkaloids bearing aminoacetal moieties and a proposed mode of action of quinocarcin.

Figure 2: (a) Synthetic plans based on modular assembly and divergent cyclizations leading to fused skeletons...

Inspired by these biosynthetic strategies, we report herein the development of parallel and four-step synthetic processes, employing manifolds 6 and 15, leading to collections of fused molecules with installations of diverse functional groups comprising aminoacetal, β-ketoimide and indole groups [31-34]. Evaluation of in vitro antitrypanosomal activities of the synthetic collections and preliminary SAR studies are also described [35-41].

Results and Discussion

First, we assembled a linear precursor 24 with installation of a p-methoxybenzyl group and an indole ring at modules 3 and 4, respectively (Scheme 1), according to a procedure previously reported in our preliminary communication [22]. Racemic manifold 6, indole-3-carbaldehyde derivative (20), tert-butylisonitrile (21) and p-methoxybenzylamine (22) were condensed in methanol under reflux to furnish a dipeptidyl product as a 1:1 diastereomeric mixture in 78% yield. N-Acetoacetylation of this intermediate was achieved by reaction with an acetylketene generated by heating of 23. Subsequent diazotransfer reaction afforded the precursor 24 with a diazoimide group in 73% yield (two steps). Cyclization of 24 and subsequent cycloaddition between the resulting carbonium ylide and the indole C2–C3 double bond efficiently proceeded by the treatment with 5 mol % Rh2(OAc)4 catalyst in benzene under reflux to afford hexacyclic scaffold 25 in 78% yield. The cyclized products were obtained as a 1:1 diastereomeric mixture of 25a and 25b and were easily separable by conventional silica-gel chromatography. X-ray analysis of crystalline 25b unambiguously determined the relative stereochemical relationships of the multiple sp3 centers embedded in the complex hexacyclic scaffold. In addition, removal of the N-nosyl protecting group by treatment with benzenethiol led to 26b in quantitative yield [42].

Scheme 1: Four-step synthesis of hexacyclic skeleton 25.

Scheme 1: Four-step synthesis of hexacyclic skeleton 25.

To generate skeletal variations by altering the sites of the cycloadditions, we next synthesized a branched precursor 29 bearing a pair of identical indole units at modules 3 and 4 (Scheme 2), as reported previously [22]. Due to the instability of the corresponding amine building block bearing the indole unit, azide 27 was employed as a precursor. Staudinger/aza-Wittig reaction [43] of 27 and 20 and subsequent condensation with 6 and 21 afforded the peptidyl product 28. Installation of a β-keto imide followed by diazotransfer reaction produced 29. Upon the treatment of 29 with Rh2(OAc)4 catalyst (5 mol %), the cycloaddition occurred in a highly site-selective manner at module 3 to form 30 in 77% yield. Cycloaddition with the other site (module 4) is likely to be hindered by the sterically demanding amide moiety (module 5) in the vicinity of the reaction centers.

Scheme 2: Four-step synthesis of hexacyclic skeleton 30.

Scheme 2: Four-step synthesis of hexacyclic skeleton 30.

Taking into account the predominant involvement of the dipolarophile installed at module 3, we then designed a branched precursor 35 having a terminal olefin and an indole group at modules 3 and 4, respectively (Scheme 3). According to the previously reported protocol [22], Ugi reaction employing allylamine (31) and stepwise installation of a diazoimide group provided 35 in good yield. Upon treatment of 35 with Rh2(OAc)4 in benzene under reflux, 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of the ylide intermediate with the terminal olefin at module 3 proceeded to give 39 as a separable 1:1 diastereomeric mixture in 94% yield. The relative stereochemistry of 39 was unambiguously determined by X-ray analysis of the crystalline 39b.

Scheme 3: Parallel and four-step synthesis of tetracyclic skeletons 39–42 and 47–48.

Scheme 3: Parallel and four-step synthesis of tetracyclic skeletons 39–42 and 47–48.

In an effort not only to verify the reaction scope of the olefinic group installed at module 3 but also to shift the reaction site (module 3→4), we then prepared a series of cyclization precursors 36–38 in order of increasing steric hindrance of the olefinic groups as reported previously [22]. Allylamines 32–34 having a di-, tri- or tetra-substituted olefin were employed to synthesize precursors 36–38 based on the unified three-step protocol. The Rh(II)-catalyzed tandem cyclization–cycloaddition of the branched precursors 36–38 exclusively occurred at module 3. The cyclized products 40–42, having the indole group at module 4 intact, were obtained in good yields. It is worth noting that the cycloadditions efficiently incorporated consecutive quaternary centers into the complex fused skeleton, overriding the considerable steric hindrance of the dipolarophiles composed of the tri- and even tetra-substituted olefin groups. To test the generality of the site-selective cycloaddition at module 3, we then synthesized precursors 45 and 46 with a terminal alkyne and a furan ring, respectively, by using amine building blocks 43 and 44 according to the reported procedure [22]. The Rh(II)-catalyzed tandem reactions of 45 and 46 again proceeded at module 3 to produce cyclized products 47 and 48 in good yields. Despite our concern for the potential instability of the aminoacetal moiety adjacent to the double bond, 47 is stable under the standard manipulations. Overall, the pair of diastereomers generated by the Ugi condensations were converted equally through the unified three-step transformations and easily separated after the cycloadditions.

Whilst the cycloadditions described above demonstrate the preference for the dipolarophile installed at module 3, we then attempted to alter the cyclization mode (module 3→4) by increasing the entropic barrier for medium-sized ring formation (Scheme 4) as reported previously [22]. For this purpose, we designed precursors 51 and 52, synthesized through the three-step protocol employing amines 49 and 50, respectively. Upon the treatment of 51 with Rh2(OAc)4, cycloaddition predominantly occurred at module 3 to produce tetracyclic 53 in 65% yield with formation of a seven-membered ring. Despite the minor pathway, cycloaddition at module 4 also competed to give 54 in 22% yield. On the other hand, cycloaddition of 52 exclusively occurred with the indole group at module 4, giving rise to 56 in 94% yield without eight-membered ring formation leading to 55. X-ray analysis of the crystalline 56b confirmed the structure [22]. Accordingly, alteration of the cyclization mode was achieved by modulating the ring sizes formed via cycloaddition, which allowed divergent access to hexacyclic and tetracyclic skeletons.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of branched precursors, 51 and 52, using amines 49 and 50, with different methylene lengths and attempts to switch reaction sites.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of branched precursors, 51 and 52, using amines 49 and 50, with different methylene lengt...

In this study, we designed and synthesized a piperidine-based manifold 15 bearing an amino group in order to produce variations of branched precursors leading to distinct scaffolds (Scheme 5). The manifold 15 was readily prepared through Curtius rearrangement of 6 and subsequent removal of the resulting carbamate group. Ugi four-component condensation of 15, isonitrile 21, indole-3-carboxylic acid derivative 58 and aldehyde 59 produced a 1:1 diastereomeric mixture of the dipeptidyl intermediate. Stepwise installation of the α-diazocarbonyl group produced 62 in good yield. The cyclization precursor 62 has a different arrangement of the branched dipeptidyl unit linked to the piperidine-based manifold compared with those derived from 6. Rhodium-catalyzed tandem cyclization–cycloaddition proceeded smoothly to produce 63 in 95% yield. After separation of the diastereomers, X-ray analysis of crystalline 63a allowed its structural determination. The flexibility and divergence of the synthetic process with high levels of stereoselectivity are promising for the development of small-molecule libraries with structural diversity and complexity.

Scheme 5: Four-step synthesis of hexacyclic scaffold 63 employing manifold 15. For details of the synthesis of 60 and 61 see Supporting Information File 1.

Scheme 5: Four-step synthesis of hexacyclic scaffold 63 employing manifold 15. For details of the synthesis o...

With collections of the natural-product-inspired molecules in hand, in vitro anti-trypanosomal activities [35-41] were evaluated by employing a GUTat 3.1 strain of T. brucei brucei (Table 1) according to the previously reported protocols (Supporting Information File 1). We found several hit compounds in the series of the cycloadducts exploiting module 3 as dipolarophiles. While compound 39a shows negligible activities, the diastereomer 39b exhibits the most potent activity (IC50 = 0.46 μg/mL), indicating the critical importance of the stereochemistry on the peptidyl unit (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). The IC50 value of the antitrypanosomal activity is comparable to or greater than those of the approved drugs, suramine and eflornithine. Unfortunately, 39b exhibits relatively potent cytotoxicity (IC50 = 4.02 μg/mL) against a human cell line (MRC-5 cells), and its selectivity index (SI) is calculated to be 8.7 as a means to assess the combined potencies of both antitrypanosomal and cytotoxic activities. Incorporation of dimethyl substituents on the scaffold resulted in diminished activity (41b: IC50 = 5.89 μg/mL) (Table 1, entry 3). Removal of the nosyl group (39b→39c) also caused substantial loss of the activities, suggesting the critical role of the aromatic sulfone amide moiety (Table 1, entry 4). Aside from 25a, which shows moderate activity (IC50 = 5.9 μg/mL) (Table 1, entry 5), the antitrypanosomal activities of hexacyclic compounds, 25b and 30b, (Table 1, entries 6 and 7) are negligible. In addition, the hexacycles (63a and 63b) generated from manifold 15 also showed insignificant activities (data not shown). Thus, this preliminary assessment supports the idea that the collections of natural-product-inspired scaffolds could have high hit rates against biological screenings, even without having structural information about the biological targets and small-molecule modulators related to the targeted cellular functions. Further screening investigations of the synthetic collections prepared in the four-step process are currently underway in our laboratories.

Table 1: In vitro anti-trypanosomal activities of natural product analogues and approved drugs against T. brucei brucei GUTat 3.1a.

| entry | compound | IC50 (μg/mL) |

Selectivity

Index (SI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

anti-trypanosomal

activity |

cytotoxicity | |||

| 1 |

39a |

>12.5 | NDb | (─) |

| 2 |

39b |

0.46 | 4.02 | 8.7 |

| 3 |

41b |

5.89 | 34.64 | 5.9 |

| 4 |

39c |

>12.5 | NDb | (─) |

| 5 |

25a |

5.9 | 24.47 | 4.1 |

| 6 |

25b |

>12.5 | NDb | (─) |

| 7 |

30b |

>12.5 | NDb | (─) |

| 8 | pentamidinec | 0.00158 | 5.71 | 3600 |

| 9 | suraminc | 1.58 | >100 | >63 |

| 10 | eflornithinec | 2.27 | >100 | >44 |

aCulture of trypanosome (2.0–2.5 × 104 trypanosomes/mL for GUTat 3.1 strain) was used. The cytotoxicities were evaluated with MRC-5 cells, and the selectivity index (SI) for trypanosomiasis was calculated as (IC50 for MRC-5)/(IC50 for T. brucei brucei). bND means “not determined”. cExisting antitrypanosomal drugs.

Conclusion

Inspired by biosynthetic strategies, we devised a modular assembly of five components employing manifold 6 and subsequent installation of a diazoimide group. This allowed three-step access to collections of cyclization precursors with a linkage of the piperidine and the indole units as key substructures shared with naturally occurring alkaloids. Rhodium-catalyzed cyclizations of diazoimides and subsequent divergent cycloadditions produced tetracyclic and hexacyclic scaffolds with exquisite regio- and stereocontrols. By the choice of dipolarophiles incorporated in modules 3 and 4, we have demonstrated site-selective cycloadditions leading to distinct scaffolds, which could be a rational approach to generate skeletal variations in synthetic collections. We further demonstrated the applicability of the manifold 15 bearing an amino group, which elicits further scaffold diversity. The parallel synthetic process based on the unified four-step sequences allows installation of dense arrays of various functional groups featuring aminoacetal, β-ketoimide and indole/olefin groups into multicyclic scaffolds reminiscent of natural products. Evaluation of antitrypanosomal activities of the collections allowed primary screenings of several hit compounds. The preliminary SAR study provided insights into the potential pharmacophore, based on the key features of scaffold, substructure and stereochemistry, which could be the proof of concept of our synthetic approach toward lead generation exploiting natural-product-inspired collections.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures and NMR spectra of compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.0 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Kiyoshi Tsuge (University of Toyama) and Yuko Fujimura (Shionogi & Co., Ltd.) for performing the X-ray analysis of crystalline compounds. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research [20651054] and Scientific Research (B) [23310156] to H. Oguri and also supported in part by FINDS: pharma-innovation discovery competition Shionogi, the Naito Foundation, the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), and the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST). A fellowship to H. M. from the JSPS is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Ms. Miyuki Namatame (Kitasato University) for her technical assistance.

References

-

Ganesan, A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008, 12, 306–317. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.03.016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, J. W.-H.; Vederas, J. C. Science 2009, 325, 161–165. doi:10.1126/science.1168243

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Clemons, P. A.; Bodycombe, N. E.; Carrinski, H. A.; Wilson, J. A.; Shamji, A. F.; Wagner, B. K.; Koehler, A. N.; Schreiber, S. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 18787–18792. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012741107

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Walsh, C. T.; Fischbach, M. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2469–2493. doi:10.1021/ja909118a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dewick, P. M. The Acetate Pathway: Fatty acids and Polyketides. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach, 3rd ed.; John Wiely & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, U.K., 2009; pp 39–135.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Saxton, J. E. Alkaloids of the Aspidospermine Group. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Cordell, G. A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 1998; Vol. 51, pp 1–197.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nielsen, T. E.; Schreiber, S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 48–56. doi:10.1002/anie.200703073

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schreiber, S. L. Nature 2009, 457, 153–154. doi:10.1038/457153a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mitchell, J. M.; Shaw, J. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1722–1726. doi:10.1002/anie.200503341

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumagai, N.; Muncipinto, G.; Schreiber, S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3635–3638. doi:10.1002/anie.200600497

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Comer, E.; Rohan, E.; Deng, L.; Porco, J. A., Jr. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2123–2126. doi:10.1021/ol070606t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sunderhaus, J. D.; Martin, S. F. Chem.–Eur. J. 2009, 15, 1300–1308. doi:10.1002/chem.200802140

Return to citation in text: [1] -

O'Leary-Steele, C.; Pedersen, P. J.; James, T.; Lanyon-Hogg, T.; Leach, S.; Hayes, J.; Nelson, A. Chem.–Eur. J. 2010, 16, 9563–9571. doi:10.1002/chem.201000707

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bauer, R. A.; DiBlasi, C. M.; Tan, D. S. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2084–2087. doi:10.1021/ol100574y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marcaurelle, L. A.; Comer, E.; Dandapani, S.; Duvall, J. R.; Gerard, B.; Kesavan, S.; Lee, M. D., IV; Liu, H.; Lowe, J. T.; Marie, J.-C.; Mulrooney, C. A.; Pandya, B. A.; Rowley, A.; Ryba, T. D.; Suh, B.-C.; Wei, J.; Young, D. W.; Akella, L. B.; Ross, N. T.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Fass, D. M.; Reis, S. A.; Zhao, W.-N.; Haggarty, S. J.; Palmer, M.; Foley, M. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16962–16976. doi:10.1021/ja105119r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schreiber, S. L. Science 2000, 287, 1964–1969. doi:10.1126/science.287.5460.1964

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Galloway, W. R. J. D.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Spring, D. R. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, No. 80. doi:10.1038/ncomms1081

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oguri, H.; Schreiber, S. L. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 47–50. doi:10.1021/ol047945w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Padwa, A.; Hornbuckle, S. F. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 263–309. doi:10.1021/cr00003a001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Padwa, A.; Weingarten, M. D. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 223–270. doi:10.1021/cr950022h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Padwa, A. Pure Appl. Chem. 2004, 76, 1933–1952. doi:10.1351/pac200476111933

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] -

Dömling, A.; Ugi, I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3168–3210. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3168::AID-ANIE3168>3.0.CO;2-U

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhu, J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 1133–1144. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200390167

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dömling, A. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 17–89. doi:10.1021/cr0505728

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reber, K. P.; Tilley, S. D.; Sorensen, E. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3022–3034. doi:10.1039/b912599j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 6577–6605. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.04.074

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hirai, G.; Oguri, H.; Hayashi, M.; Koyama, K.; Koizumi, Y.; Moharram, S. M.; Hirama, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 2647–2651. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.02.064

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scott, J. D.; Williams, R. M. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1669–1730. doi:10.1021/cr010212u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hill, G. C.; Wunz, T. P.; Remers, W. A. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 1988, 2, 91–106. doi:10.1007/BF01532085

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boldi, A. M. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004, 8, 281–286. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.04.010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumar, K.; Waldmann, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3224–3242. doi:10.1002/anie.200803437

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bauer, R. A.; Wurst, J. M.; Tan, D. S. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 308–314. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.02.001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ishigaki, Y.; Mahendar, V.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3304–3305. doi:10.1039/b926676c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oguri, H.; Hiruma, T.; Yamagishi, Y.; Oikawa, H.; Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7096–7105. doi:10.1021/ja200374q

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Otoguro, K.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara, A.; Furusawa, T.; Masuma, R.; Shiomi, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2008, 61, 372–378. doi:10.1038/ja.2008.52

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Toriizuka, Y.; Kinoshita, E.; Kogure, N.; Kitajima, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S.; Takayama, H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 10182–10189. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.061

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara, A.; Nonaka, K.; Kinoshita, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Masuma, R.; Shiomi, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62, 303–308. doi:10.1038/ja.2009.32

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Iwatsuki, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; Niitsuma, M.; Hashida, J.; Mori, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Nonaka, K.; Masuma, R.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Shiomi, K.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2010, 63, 331–333. doi:10.1038/ja.2010.41

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Kiyohara, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Asakawa, Y.; Ōmura, S.; Yamada, H. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 2024–2030. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.07.015

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Onodera, H.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2012, 65, 113–114. doi:10.1038/ja.2011.118

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Fukuyama, T.; Jow, C.-K.; Cheung, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 6373–6374. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)01316-A

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Timmer, M. S. M.; Risseeuw, M. D. P.; Verdoes, M.; Filippov, D. V.; Plaisier, J. R.; van der Marel, G. A.; Overkleeft, H. S.; van Boom, J. H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2005, 16, 177–185. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.079

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Ganesan, A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008, 12, 306–317. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.03.016 |

| 2. | Li, J. W.-H.; Vederas, J. C. Science 2009, 325, 161–165. doi:10.1126/science.1168243 |

| 3. | Clemons, P. A.; Bodycombe, N. E.; Carrinski, H. A.; Wilson, J. A.; Shamji, A. F.; Wagner, B. K.; Koehler, A. N.; Schreiber, S. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 18787–18792. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012741107 |

| 7. | Nielsen, T. E.; Schreiber, S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 48–56. doi:10.1002/anie.200703073 |

| 8. | Schreiber, S. L. Nature 2009, 457, 153–154. doi:10.1038/457153a |

| 9. | Mitchell, J. M.; Shaw, J. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1722–1726. doi:10.1002/anie.200503341 |

| 10. | Kumagai, N.; Muncipinto, G.; Schreiber, S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3635–3638. doi:10.1002/anie.200600497 |

| 11. | Comer, E.; Rohan, E.; Deng, L.; Porco, J. A., Jr. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2123–2126. doi:10.1021/ol070606t |

| 12. | Sunderhaus, J. D.; Martin, S. F. Chem.–Eur. J. 2009, 15, 1300–1308. doi:10.1002/chem.200802140 |

| 13. | O'Leary-Steele, C.; Pedersen, P. J.; James, T.; Lanyon-Hogg, T.; Leach, S.; Hayes, J.; Nelson, A. Chem.–Eur. J. 2010, 16, 9563–9571. doi:10.1002/chem.201000707 |

| 14. | Bauer, R. A.; DiBlasi, C. M.; Tan, D. S. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2084–2087. doi:10.1021/ol100574y |

| 15. | Marcaurelle, L. A.; Comer, E.; Dandapani, S.; Duvall, J. R.; Gerard, B.; Kesavan, S.; Lee, M. D., IV; Liu, H.; Lowe, J. T.; Marie, J.-C.; Mulrooney, C. A.; Pandya, B. A.; Rowley, A.; Ryba, T. D.; Suh, B.-C.; Wei, J.; Young, D. W.; Akella, L. B.; Ross, N. T.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Fass, D. M.; Reis, S. A.; Zhao, W.-N.; Haggarty, S. J.; Palmer, M.; Foley, M. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16962–16976. doi:10.1021/ja105119r |

| 31. | Boldi, A. M. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004, 8, 281–286. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.04.010 |

| 32. | Kumar, K.; Waldmann, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3224–3242. doi:10.1002/anie.200803437 |

| 33. | Bauer, R. A.; Wurst, J. M.; Tan, D. S. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 308–314. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.02.001 |

| 34. | Ishigaki, Y.; Mahendar, V.; Oguri, H.; Oikawa, H. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3304–3305. doi:10.1039/b926676c |

| 6. | Saxton, J. E. Alkaloids of the Aspidospermine Group. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Cordell, G. A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 1998; Vol. 51, pp 1–197. |

| 35. | Oguri, H.; Hiruma, T.; Yamagishi, Y.; Oikawa, H.; Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7096–7105. doi:10.1021/ja200374q |

| 36. | Otoguro, K.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara, A.; Furusawa, T.; Masuma, R.; Shiomi, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2008, 61, 372–378. doi:10.1038/ja.2008.52 |

| 37. | Toriizuka, Y.; Kinoshita, E.; Kogure, N.; Kitajima, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S.; Takayama, H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 10182–10189. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.061 |

| 38. | Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara, A.; Nonaka, K.; Kinoshita, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Masuma, R.; Shiomi, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62, 303–308. doi:10.1038/ja.2009.32 |

| 39. | Iwatsuki, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; Niitsuma, M.; Hashida, J.; Mori, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Nonaka, K.; Masuma, R.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Shiomi, K.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2010, 63, 331–333. doi:10.1038/ja.2010.41 |

| 40. | Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Kiyohara, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Asakawa, Y.; Ōmura, S.; Yamada, H. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 2024–2030. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.07.015 |

| 41. | Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Onodera, H.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2012, 65, 113–114. doi:10.1038/ja.2011.118 |

| 5. | Dewick, P. M. The Acetate Pathway: Fatty acids and Polyketides. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach, 3rd ed.; John Wiely & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, U.K., 2009; pp 39–135. |

| 28. | Hirai, G.; Oguri, H.; Hayashi, M.; Koyama, K.; Koizumi, Y.; Moharram, S. M.; Hirama, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 2647–2651. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.02.064 |

| 29. | Scott, J. D.; Williams, R. M. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1669–1730. doi:10.1021/cr010212u |

| 4. | Walsh, C. T.; Fischbach, M. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2469–2493. doi:10.1021/ja909118a |

| 30. | Hill, G. C.; Wunz, T. P.; Remers, W. A. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 1988, 2, 91–106. doi:10.1007/BF01532085 |

| 22. | Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a |

| 26. | Reber, K. P.; Tilley, S. D.; Sorensen, E. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3022–3034. doi:10.1039/b912599j |

| 19. | Padwa, A.; Hornbuckle, S. F. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 263–309. doi:10.1021/cr00003a001 |

| 20. | Padwa, A.; Weingarten, M. D. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 223–270. doi:10.1021/cr950022h |

| 21. | Padwa, A. Pure Appl. Chem. 2004, 76, 1933–1952. doi:10.1351/pac200476111933 |

| 27. | Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 6577–6605. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.04.074 |

| 16. | Schreiber, S. L. Science 2000, 287, 1964–1969. doi:10.1126/science.287.5460.1964 |

| 17. | Galloway, W. R. J. D.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Spring, D. R. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, No. 80. doi:10.1038/ncomms1081 |

| 23. | Dömling, A.; Ugi, I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3168–3210. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3168::AID-ANIE3168>3.0.CO;2-U |

| 24. | Zhu, J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 1133–1144. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200390167 |

| 25. | Dömling, A. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 17–89. doi:10.1021/cr0505728 |

| 22. | Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a |

| 22. | Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a |

| 42. | Fukuyama, T.; Jow, C.-K.; Cheung, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 6373–6374. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)01316-A |

| 35. | Oguri, H.; Hiruma, T.; Yamagishi, Y.; Oikawa, H.; Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7096–7105. doi:10.1021/ja200374q |

| 36. | Otoguro, K.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara, A.; Furusawa, T.; Masuma, R.; Shiomi, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2008, 61, 372–378. doi:10.1038/ja.2008.52 |

| 37. | Toriizuka, Y.; Kinoshita, E.; Kogure, N.; Kitajima, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S.; Takayama, H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 10182–10189. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.061 |

| 38. | Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara, A.; Nonaka, K.; Kinoshita, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Masuma, R.; Shiomi, K.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62, 303–308. doi:10.1038/ja.2009.32 |

| 39. | Iwatsuki, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; Niitsuma, M.; Hashida, J.; Mori, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Nonaka, K.; Masuma, R.; Otoguro, K.; Yamada, H.; Shiomi, K.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2010, 63, 331–333. doi:10.1038/ja.2010.41 |

| 40. | Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Ishiyama, A.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Kiyohara, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Asakawa, Y.; Ōmura, S.; Yamada, H. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 2024–2030. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.07.015 |

| 41. | Ishiyama, A.; Otoguro, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tsukashima, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Onodera, H.; Yamada, H.; Ōmura, S. J. Antibiot. 2012, 65, 113–114. doi:10.1038/ja.2011.118 |

| 22. | Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a |

| 22. | Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a |

| 22. | Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a |

| 22. | Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a |

| 43. | Timmer, M. S. M.; Risseeuw, M. D. P.; Verdoes, M.; Filippov, D. V.; Plaisier, J. R.; van der Marel, G. A.; Overkleeft, H. S.; van Boom, J. H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2005, 16, 177–185. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.079 |

| 22. | Mizoguchi, H.; Oguri, H.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3016–3019. doi:10.1021/ol901020a |

© 2012 Oguri et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)