Abstract

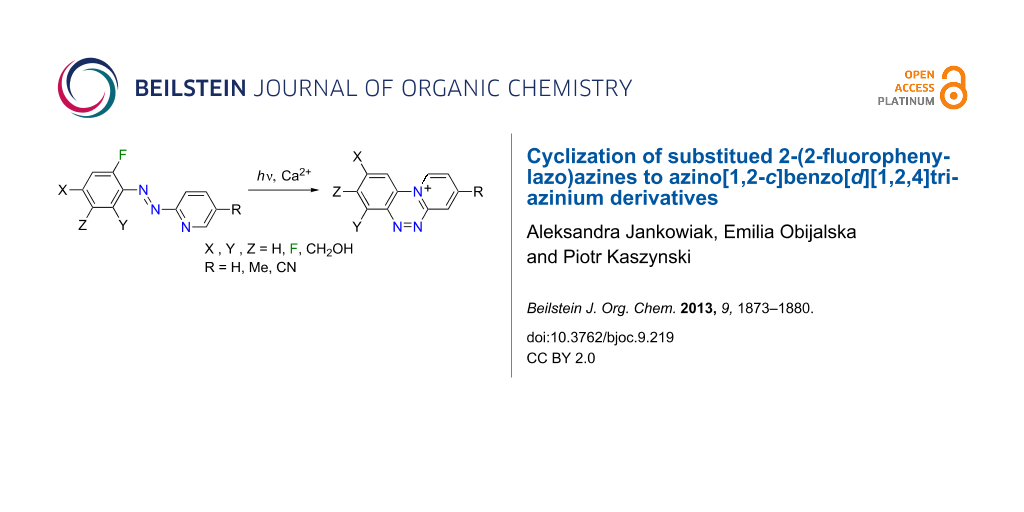

Light-induced cyclization of several substituted 2-(2-fluorophenylazo)azines in the presence of Ca2+ ions to the corresponding triazinium derivatives is investigated experimentally and computationally. The azo derivatives of 4-methylpyridine 4 undergo facile cyclization to the corresponding triazinium 1, and the rate of cyclization increases with increasing number of fluorine atoms at the benzene ring. No triazinium ions were obtained from azo derivatives of 4-cyanopyridine, pyrazine and pyrimidine, presumably due to their instability under the reaction conditions. The experimental results and mechanism are discussed with the aid of DFT computational results.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Derivatives of benzo[c]quinolizinium [1-4] (I, X = Y = CH, Figure 1) and its di-aza analogue pyrido[2,1-c]benzo[d][1,2,4]triazinium (I, X = Y = N) belong to a class of tricyclic cations featuring general structure I and are of general interest because of their biological activity. For instance, it was demonstrated that the parent cation 1a intercalates into the minor grove of DNA [5] and to be cytotoxic to cisplatinum-resistant tumor cell lines [6]. Several of its derivatives containing Cl, Br, Me and OMe substituents at the benzene ring were prepared by acid-catalyzed photoinduced cyclization of phenylazopyridines [5]. Recently, we demonstrated an efficient alternative method for the formation of 1a and other parent tricyclic azinium cations of general structure I (A = B = H) by light-induced intramolecular cyclization of fluorides II (Figure 1) in the presence of Ca2+ ions [7].

Figure 1: Structures of cations I and precursors II.

Figure 1: Structures of cations I and precursors II.

A further progress in the investigation of cation 1a and its applications as a pharmacophore or a component of organic materials requires access to functionalized derivatives, in which substituents control the properties and allow the incorporation into more complex molecular structures. As the first step towards these goals we tested the suitability of our previously described method [7] for the synthesis of several derivatives of 1a and also for two other azines. Initially we selected CH3, CN and F substituents to investigate the reactivity of the azines, and CH2OH to provide a potential synthetic handle for the incorporation into more complex structures. Here we present the synthesis of four substituted derivatives of 1a and investigate the preparation of cations derived from pyrazine 2 and pyrimidine 3 shown in Figure 2. Our experimental results are augmented with DFT computational results.

Figure 2: Structures of triazinium cations 1–3.

Figure 2: Structures of triazinium cations 1–3.

Results and Discussion

Cyclization and cation formation

Salts 1 were prepared by photocyclization of the corresponding azo derivatives 4 in the presence of Ca2+ ions in aqueous MeCN (Scheme 1). Diazenes 4 show weak absorption bands in the visible (e.g. 452 nm, log ε = 2.6 for 4c), while salts 1 exhibit only a weak tailing absorption above 400 nm, as shown for 4c and 1c in Figure 3. Therefore irradiation was effectively conducted in Pyrex vessels.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of triazinium cations 1. Reagents and conditions: i) hν (halogen lamp or sunlight), Ca2+, MeCN/H2O (9:1).

Scheme 1: Synthesis of triazinium cations 1. Reagents and conditions: i) hν (halogen lamp or sunlight), Ca2+,...

![[1860-5397-9-219-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-219-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Electronic absorption spectra for 1c and 4c (MeCN). Blue lines represent magnified areas of the spectra.

Figure 3: Electronic absorption spectra for 1c and 4c (MeCN). Blue lines represent magnified areas of the spe...

The cyclization of 2-fluorophenylazopyridines 4b and 4e was conducted using a 500 W halogen lamp in the presence of Ca(OTs)2 [7], and cations 1b and 1e were isolated as tosylates in 75% and 95% yield, respectively. Under these conditions diazenes 4c and 4d underwent cyclization, but the resulting cations 1c and 1d were unstable and partially decomposed during the reaction. Therefore, their cyclization was carried out with sunlight and tosylate 1c was isolated in pure form in 90% yield. In contrast, cation 1d partially decomposed during the workup, presumably due to the activation by means of the fluorine atoms and their electron-withdrawing effect. A pure sample of 1d could not be isolated. A comparison of the cyclization rates of the three fluorophenylazo derivatives 4b–4d was conducted in NMR tubes exposed to sunlight. The experiment demonstrated that the rate of cyclization increases with increasing number of fluorine atoms, and after 1 h conversion of 4b to 1b was 30%, 4c to cation 1c 80%, and 4d to 1d was complete. Full conversion of 4b to 1b was achieved after 5 h. It should be pointed out that the cyclization and formation of the cations requires both light and Ca2+ ions, and no product formation was observed if one of them is absent. While in most experiments Ca(OTs)2 served as a source of Ca2+, in some other CaCl2 was used, and the Cl− anion was later replaced by TsO−.

Attempts to cyclize the cyano derivative 4f, using a halogen lamp were unsuccessful and after 3 h only decomposition products were observed by 1H NMR along with some residual starting 4f. No characteristic NMR pattern that could be ascribed to the cation 1f was detected. Similarly unsuccessful were the attempts to cyclize azopyrazine 5 (halogen lamp/ice bath or sunlight, Figure 4) and azopyrimidine 6 (halogen lamp/reflux); instead complex mixtures of products were obtained.

Figure 4: Strcutures of trans azo derivatives 5-E and 6-E.

Figure 4: Strcutures of trans azo derivatives 5-E and 6-E.

Synthesis of azo precursors

Azo compounds 4b–4e were prepared in 38%–90% yield using method A (Scheme 2) in which 2-nitroso-4-picoline (7) [8] was condensed with 2-fluoroaniline (8a) or its derivatives 8c–8e. The 2-fluoro-5-hydroxymethylaniline (8e) was obtained according to a literature procedure [9]. 4-Cyano derivative 4f was prepared in 50% yield by method B [7,10] involving condensation of 2-amino-4-cyanopyridine with 1-fluoro-2-nitrosobenzene (9) [7]. Azoazines 5 and 6 were obtained in a similar way by condensation of 9 with 2-aminopyrazine and 2-aminopyrimidine, respectively, and their preparation was described before [11].

Scheme 2: Synthesis of azo precursors. Reagents and conditions: i) AcOH cat, CH2Cl2, rt, 25 h; ii) toluene, 50% NaOH, 50 °C, 25 min; iii) NCS, Me2S, CH2Cl2, –20 °C; iv) mCPBA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; v) Oxone®, CH2Cl2/H2O rt, 25 h.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of azo precursors. Reagents and conditions: i) AcOH cat, CH2Cl2, rt, 25 h; ii) toluene, 5...

Interestingly, the trifluoro derivative 4d had exceptionally limited thermal stability: After heating at 60 °C in CDCl3 it was converted to another species also containing the picoline fragment, according to the 1H NMR analysis. The new compound did not undergo photocyclization and was not analyzed further.

Mechanistic and computational analyses

The proposed mechanism for the formation of the triazinium cations from fluorophenylazoazines involves a photo-induced trans-to-cis isomerization of the azo group followed by Ca2+-assisted cyclization (Scheme 3) [7], which, in principle, can proceed either thermally or photochemically. Thus, the success of the reaction depends on i) the efficient access to the Z-isomer, and ii) the relative rates of cyclization vs back isomerization to the E-isomer. The supply of the requisite Z-isomers of the azoazines is best accomplished by photoisomerization of the E-isomers, since the Z-isomers cannot be populated thermally due to the high E → Z thermal isomerization barrier (ΔG‡298 > 35 kcal/mol) [7]. The Z-forms however, thermally and also photochemically isomerize back to the more stable E-isomers, and the rates are substituent depended [12]. Thus, with the broadband irradiation a photostationary state establishes providing a constant ratio of Z- to E-isomers.

Scheme 3: Formation of cations 1 from diazenes 4.

Scheme 3: Formation of cations 1 from diazenes 4.

Previous analyses suggested [7] that the cyclization of 4-Z involves 6 π electrons leading to non-aromatic product 10, which upon Ca2+-assisted departure of the fluoride undergoes aromatization and formation of cation 1. In this work, the theoretical analysis is concentrated on the effect of substituents and on the type of azine on the formation of the cations. Therefore the cyclization of cis-azoazines 4-Z–6-Z was investigated at B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)//B3LYP/6-311G(2d,p) level of theory in MeCN as dielectric medium without participation of metal ions. The computational studies were expanded by inclusion of 4g-Z– 4i-Z for a better understanding of the structure–reactivity relationship. The resulting free energy differences between the Z-isomers, relevant to the cyclization process, and the cyclic products, and free energy of activation for a series of diazenes are listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1: Calculated free energy activation and change (kcal/mol) for the cyclization of cis-azopyridine 4-Z to the nonaromatic product 10 in MeCN (Scheme 3).a

| R | X | Y | Z | ΔG‡298b | ΔG298c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | H | H | H | H | 22.4 | 5.7 |

| b | Me | H | H | H | 23.1 | 5.7 |

| c | Me | F | H | H | 18.5 | 2.4 |

| d | Me | F | F | H | 18.9 | 4.6 |

| f | CN | H | H | H | 23.3 | 5.2 |

| g | OMe | H | H | H | 23.5 | 4.5 |

| h | Me | H | H | OMe | 23.2 | 3.9 |

| i | Me | H | H | CN | 19.0 | 4.8 |

aCalculations at B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)//B3LYP/6-311G(2d,p) level with MeCN as dielectric medium. bEnergy of the transition state 10-TS. cEnergy difference between product 10 and azopyridine 4-Z.

Table 2: Calculated free energy activation and change (kcal/mol) for cyclization of cis-azoazines to the nonaromatic product in MeCN.a

| reaction | ΔG‡298b | ΔG298c |

|---|---|---|

| 4a-Z → 10a | 22.4 | 5.7 |

| 5-Z → 11 | 18.7 | 2.7 |

| 6-Z → 12 | 25.0 | 7.5 |

aCalculations at B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)//B3LYP/6-311G(2d,p) level in MeCN as dielectric medium. bEnergy of the transition state. cEnergy difference between the cyclic product and azoazine.

The results in Table 1 and Table 2 show that the free energy of activation, ΔG‡298, required for the cyclization of all considered azoazines is in a range of 18–25 kcal/mol, and the process is endergonic by about 5 kcal/mol. Thus, for all investigated compounds the cyclization is thermally accessible and also thermally reversible at ambient temperature. These computational results are consistent with experimental observations, that all azoazines reacted, however only 5 cations (1a–1e) were isolated. The remaining cations, 1f, 2 and 3, could have been formed, but were presumably unstable under the reaction conditions, as already observed for 1d. Also consistent with the computational results is the observation that the formation of 1 requires a fluoride scavenger, apparently for the aromatization of the cyclic product.

The analysis of species involved in the cyclization demonstrates that the C…N and C–F distances change similarly for all azoazines in the process regardless of the substituent. Thus, the C…N distance decreases by 1.232 Å from 3.150 ± 0.03 Å in the cis-azoazine to 1.918 ± 0.009 Å in the transition state (TS) and then to 1.457 ± 0.004 Å in the cycloadduct, as shown for the cyclization of 4c to 10c in Figure 5. At the same time the C–F distance increases only by about 2% from 1.350 ± 0.002 Å in the cis-azoazine to 1.374 ± 0.003 Å in the TS. A more significant increase in the C–F distance, by 7%, is observed in the cyclic product (1.445 ± 0.005 Å).

![[1860-5397-9-219-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-219-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: B3LYP/6-311G(2d,p)-optimized geometries for structures involved in cyclization of 4c to 1c.

Figure 5: B3LYP/6-311G(2d,p)-optimized geometries for structures involved in cyclization of 4c to 1c.

A detailed analysis of the DFT results for the azopyridine series demonstrates that the rate of cyclization only correlates with the character of the substituent at the benzene ring and does not depend on the pyridine ring. For a simple nucleophilic aromatic ipso-substitution reaction (NAS) electron-donating groups in the C(4) position of the pyridine ring in 4 should increase the reaction rate. Computational results demonstrate the contrary and as the electron donation of the substituent R increases in the order H (4a) < CH3 (4b) < OCH3 (4g) so does the activation energy (Table 1). In contrast, increasing electron withdrawing ability of the substituent Z in the para-position to the leaving fluorine atom increases the reaction rate as observed in a series 4h (Z = OCH3, ΔG‡298 = 23.2 kcal/mol), 4a (Z = H, ΔG‡298 = 22.4 kcal/mol), and 4i (Z = CN, ΔG‡298 = 19.0 kcal/mol) in Table 1.

For further probing of the cyclization mechanism, the mildly activating [13,14] N=N-bridging group in 4c–Z was replaced by the non-activating CH=CH group in 13-Z (Figure 6). A computational analysis demonstrated that this structural modification resulted in a modest increase of activation energy ΔG‡298 for the cyclization by 3.1 kcal/mol. However, replacement of the bridging π-bond with the aliphatic CH2CH2 group in compound 14 prevents the cyclization process, and the analogous cyclic product could not be located on the potential energy surface. These results indicate that the cyclization process involves 6 π electrons, which allows the formation of the non-zwitterionic product such as 10. Comparison of cyclization of 4c-Z and 13-Z further demonstrates that the activation energy is lower for the azene than for the analogues stilbene, which presumably is related to the electronegativity of the bridging group.

Figure 6: Structures of three close analogues.

Figure 6: Structures of three close analogues.

The analysis of the data of three fluoro derivatives 4b–4d in Table 1 demonstrates that the addition of one or two fluorine atoms at the benzene ring in 4b significantly lowers the activation barrier for the cyclization, by about 4.5 kcal/mol, for 4c-Z and 4d-Z, which is consistent with the accellerated formation of cations 1c and 1d observed experimentally. Interestingly, a bigger effect is predicted for the 2,4-difluorophenyl derivative 4c than for the 2,4,6-trifluorophenyl analogue 4d.

Among the three parent azoazines the least unfavorable cyclization is calculated for the pyrazine derivative 5-Z (ΔG298 = 2.7 kcal/mol), which also has the lowest TS energy (ΔG‡298 = 18.7 kcal/mol, Table 2). On the other hand, the cyclization of pyrimidine 6-Z is most endergonic and has the highest TS energy among all azoazines considered in this work. These significant differences between the three parent azoazines can be explained with lower aromaticity of the pyrazine ring [15], and with the electropositive character of the N(1) position of the pyrimidine ring, when compared to the pyridine analogue. These two factors may also contribute to the higher reactivity of cations 2 and 3 and hence their apparent instability under the reaction conditions.

Conclusion

A DFT computational analysis indicates that the cyclization of cis-fluorophenylazoazines can occur thermally at room temperature for all considered compounds. The reaction is endergonic with 2.4–7.5 kcal/mol, and the formation of the triazinium cations is accomplished by aromatization of the cyclic product by Ca2+ ion-assisted removal of the fluoride. These results are supported by experimental data, which demonstrate a facile conversion of all azoazines under the reaction conditions, although only 5 out of 8 triazinium salts were isolated. The remaining three, all of them containing a CN substituent and derived from pyrazine and pyrimidine, are presumably too reactive under the reaction conditions to be isolated in pure form.

A brief computational investigation of the mechanism demonstrates the importance of the unsaturated bridge in the cyclization step and points towards a 6π-electrocyclization rather than to a simple nucleophilic aromatic displacement mechanism.

Among the triazinium salts prepared in this work is the hydroxymethyl derivative 1e, which, in principle, can be incorporated into more complex molecular structures.

Computational Details

The quantum-mechanical calculations were carried out at B3LYP/6-311G(2d,p) level of theory using the Gaussian 09 suite of programs [16]. The geometry optimizations were undertaken using tight convergence limits and with no symmetry constraints. Vibrational frequencies were used to characterize the nature of the stationary points. Zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections were scaled by 0.9806 [17]. Transition state structures for cyclization reactions were located using the STQN method [18] requested with the QST2 keyword and default convergence criteria. Final energies for each optimized structure were calculated with the B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p)//B3LYP/6-311G(2d,p) method in MeCN as dielectric medium using the IPCM model [19] requested with the SCRF=IPCM keyword (epsilon = 36.64).

Experimental

General remarks

Melting points are uncorrected. NMR spectra were recorded at 300 MHz (1H) and 100 MHz (13C) in CD3CN, DMSO-d6 or CDCl3 and chemical shifts are refered to the solvent peaks (1.96, 2.54 and 7.26 ppm, respectively).

Photocyclization and preparation of salts 1. General Porcedure

Method A [7]: Azo compound 4 (1.0 mmol) and calcium p-toluenesulfonate (190 mg 0.5 mmol) or calcium chloride (56 mg, 0.5 mmol) were dissolved in a mixture of MeCN/H2O (9:1, 30 mL). The resulted solution was irradiated with a 500 W halogen lamp and gently refluxed until TLC control showed full conversion of the substrate (about 1.5 h). The solvents were evaporated. The residue was dried in a desiccator over P2O5 (12 h). The solid was washed with CH2Cl2, the residue was dissolved in hot MeCN and filtered. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was recrystallized from aqueous MeCN.

Method B: The reaction mixture prepared as in method A was exposed to intense sunlight, while stirring until TLC control showed full conversion of the substrate (about 1.5 h). The work-up of the reaction mixture was as described in method A.

3-Methylpyrido[2,1-c][1,2,4]benzotriazin-11-ium p-toluenesulfonate (1b): Method A, yield 95%: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3CN) δ 2.33 (s, 3H), 2.98 (s, 3H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.35 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 8.83 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 9.03 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 9.12 (s, 1H), 9.87 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H); HRMS m/z calcd for C12H10N3, 196.0869; found, 196.0892.

9-Fluoro-3-methylpyrido[2,1-c][1,2,4]benzotriazin-11-ium p-toluenesulfonate (1c): Method B, yield 90%: mp >190 °C dec.; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3CN) δ 2.35 (s, 3H), 2.96 (s, 3H), 7.19 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 8.11 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (dd, J1 = 9.2 Hz, J2 = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 9.00–9.60 (m, 1H), 9.11 (s, 1H), 9.73 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 20.8, 21.8, 104.1 (d, J = 30 Hz), 121.8 (d, J = 25 Hz), 125.5, 128.0, 129.7, 130.2, 132.3, 135.7 (d, J = 11 Hz), 137.5, 138.9, 141.9, 145.8, 160.6; UV–vis (MeCN) λmax (log ε) 225 (4.20), 254 (4.41), 262 sh (4.38), 365 (3.98), 379 sh (3.81); anal. calcd for C19H16FN3O3S: C, 59.21; H, 4.18; N, 10.90; found: C, 58.92; H, 4.09; N, 10.95.

7,9-Difluoro-3-methylpyrido[2,1-c][1,2,4]benzotriazin-11-ium chloride (1d): Method B, yield 40–80% (based on NMR): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3CN) δ 2.98 (s, 3H), 7.99 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 9.16 (s, 1H), 9.77 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H).

8-Hydroxymethyl-3-methylpyrido[2,1-c][1,2,4]benzotriazin-11-ium p-toluenesulfonate (1e): Method A, yield 75%: mp >150 °C dec.; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 2.32 (s, 3H), 2.98 (s, 3H), 4.97 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 5.92 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.49 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.95 (s, 1H), 9.17 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 9.35 (s, 1H), 10.36 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 20.8, 21.6, 61.6, 116.4, 121.8, 125.5, 128.0, 128.1, 129.6, 130.2, 131.9, 136.6, 137.6, 141.2, 142.0, 145.7, 148.2, 159.2; anal. calcd for C20H19N3O4S: C, 60.44; H, 4.82; N, 10.57; found: C, 60.15; H, 4.78; N, 10.47.

Azo compounds 4. A general procedure

Method A. To the solution of amine (1.0 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (2 mL), 2-nitroso-4-picoline (7, 1.0 mmol) was added followed by a catalytic amount (1 drop) of acetic acid. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 24 h, protected from a light. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified on a silica gel plug (CH2Cl2/EtOAc, 5:1) to give the corresponding azo compound as orange-red crystals. Analytically pure samples were obtained by recrystallization (hexane/CH2Cl2).

2-(2-Fluorophenylazo)picoline (4b): Yield: 83%: mp 78–80 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.48 (s, 3H), 7.18–7.34 (m, 3H), 7.48–7.56 (m, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.90 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 21.2, 114.5, 117.1 (d, J = 20 Hz), 117.9, 124.3 (d, J = 4 Hz), 126.5, 133.7 (d, J = 4 Hz), 140.4 (d, J = 6 Hz), 149.3, 149.8, 160.7 (d, J = 258 Hz), 163.3; anal. calcd for C12H10FN3: C, 66.97; H, 4.68; N, 19.52; found: C, 66.93; H, 4.66; N, 19.41.

2-(2,4-Difluorophenylazo)picoline (4c): Yield 90%: mp 99–101 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3CN) δ 2.48 (s, 3H), 7.14 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (ddd, J1 = 11.3 Hz, J2 = 8.7 Hz, J3 = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.91 (dd, J1 = 15.3 Hz, J2 = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.48 (s, 3H), 6.92–7.08 (m, 2H), 7.26 (d, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 21.1, 105.1 (t, J = 24 Hz), 112.0 (dd, J1 = 27 Hz, J2 = 4 Hz), 114.5, 119.3 (d, J = 10 Hz), 126.5, 137.3 (dd, J1 = 7 Hz, J2 = 4 Hz), 149.2, 149.8, 161.2 (dd, J1 = 260 Hz, J2 = 7 Hz),163.1, 165.3 (dd, J1 = 255 Hz, J2 = 12 Hz); UV–vis (MeCN) λmax (log ε) 225 (4.02), 322 (4.22), 541 (6.61); anal. calcd for C12H9F2N3: C, 61.80; H, 3.89; N, 18.02; found: C, 61.79; H, 3.79; N, 17.92.

2-(2,4,6-Trifluorophenylazo)picoline (4d): Yield 38%: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3CN) δ 2.49 (s, 3H), 6.85 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (d, 1H), 7.56 (s, 1H), 8.58 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.48 (s, 3H), 7.09 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (d, 1H), 7.61 (s, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H); HRMS m/z calcd for C12H9F3N2, 252.0749; found, 252.0738.

2-(2-Fluoro-5-hydroxymethylphenylazo)picoline (4e): Yield 69%: mp 154–155 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.48 (s, 3H), 4.73 (s, 2H), 7.28–7.32 (m, 1H), 7.52–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 21.2, 64.0, 114.3, 115.9, 117.2 (d, J = 20 Hz), 126.6, 132.2 (d, J = 8 Hz), 137.6 (d, J = 4 Hz), 140.0 (d, J = 7 Hz), 149.1, 150.0, 160.0 (d, J = 257 Hz), 163.1; anal. calcd for C13H12FN3O: C, 63.66; H, 4.93; N, 17.13; found: C, 63.94; H, 4.88; N, 17.20.

4-Cyano-2-(2-fluorophenylazo)pyridine (4f): Method B. 4-Cyano-2-aminopyridine (238 mg, 2.0 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (3 mL) and a 50% aqueous solution of NaOH (1.5 mL) and 2-fluoronitrosobenzene [7] (9, 293 mg, 2.3 mmol) was added. The mixture was vigorously stirred at 50 °C for 25 min. After cooling, water was added, and the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2. Extracts were dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent was evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexane/CH2Cl2) to give 230 mg (50% yield) of azo derivative 4f as an orange solid: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3CN) δ 7.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (t, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), 7.62– 7.72 (m, 1H), 7.76–7.88 (m, 2H), 8.02 (s, 1H), 8.89 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.27–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.56–7.61 (m, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (s, 1H), 8.93 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN) δ, 116.8, 117.0, 118.2, 118.3, 123.2, 125.6 (d, J = 6 Hz), 127.9, 135.9 (d, J = 8 Hz), 140.7 (d, J = 7 Hz), 151.4, 161.3 (d, J = 257 Hz), 164.0; anal. calcd for C12H7FN4: C, 63.71; H, 3.12; N, 24.77; found: C, 63.81; H, 3.14; N, 24.61.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: General methods and synthetic procedures. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 394.7 KB | Download |

References

-

Norez, C.; Bilan, F.; Kitzis, A.; Mettey, Y.; Becq, F. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 325, 89–99. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.134502

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Roomans, G. M. Am. J. Respir. Med. 2003, 2, 413–431. doi:10.1007/BF03256668

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prost, A.-L.; Dérand, R.; Gros, L.; Becq, F.; Vivaudou, M. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 66, 425–430. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00289-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Galietta, L. J. V.; Springsteel, M. F.; Eda, M.; Niedzinski, E. J.; By, K.; Haddadin, M. J.; Kurth, M. J.; Nantz, M. H.; Verkman, A. S. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 19723–19728. doi:10.1074/jbc.M101892200

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sinan, M.; Panda, M.; Ghosh, A.; Dhara, K.; Fanwick, P. E.; Chattopadhyay, D. J.; Goswami, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5185–5193. doi:10.1021/ja710211u

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Garza-Ortiz, A.; den Dulk, H.; Brouwer, J.; Kooijman, H.; Spek, A. L.; Reedijk, J. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007, 101, 1922–1930. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.05.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] -

Taylor, E. C.; Tseng, C. P.; Rampal, J. B. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 552–555. doi:10.1021/jo00342a035

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Carroll, W. A.; Altenbach, R. J.; Bai, H.; Brioni, J. D.; Brune, M. E.; Buckner, S. A.; Cassidy, C.; Chen, Y.; Coghlan, M. J.; Daza, A. V.; Drizin, I.; Fey, T. A.; Fitzgerald, M.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Gregg, R. J.; Henry, R. F.; Holladay, M. W.; King, L. L.; Kort, M. E.; Kym, P. R.; Milicic, I.; Tang, R.; Turner, S. C.; Whiteaker, K. L.; Yi, L.; Zhang, H.; Sullivan, J. P. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 3163–3179. doi:10.1021/jm030356w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Campbell, N.; Henderson, A. W.; Taylor, D. J. Chem. Soc. 1953, 1281–1285. doi:10.1039/jr9530001281

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Jankowiak, A.; Young, V. G. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 1339–1348. doi:10.1016/j.poly.2011.02.023

Return to citation in text: [1] -

García-Amorós, J.; Velasco, D. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 1003–1017. doi:10.3762/bjoc.8.113

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manka, J. T.; McKenzie, V. C.; Kaszynski, P. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 1967–1971. doi:10.1021/jo0302399

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fryszkowska, A.; Tilford, R. W.; Guo, F.; Kaszynski, P. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 2327–2333. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2005.01.023

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Katritzky, A. R.; Barczynski, P.; Musumarra, G.; Pisano, D.; Szafran, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7–15. doi:10.1021/ja00183a002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gaussian 09, Revision A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scott, A. P.; Radom, L. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 16502–16513. doi:10.1021/jp960976r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, C.; Ayala, P. Y.; Schlegel, H. B.; Frisch, M. J. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 49–56. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19960115)17:1<49::AID-JCC5>3.3.CO;2-#

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Foresman, J. B.; Keith, T. A.; Wiberg, K. B.; Snoonian, J.; Frisch, M. J. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 16098–16104. doi:10.1021/jp960488j

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 13. | Manka, J. T.; McKenzie, V. C.; Kaszynski, P. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 1967–1971. doi:10.1021/jo0302399 |

| 14. | Fryszkowska, A.; Tilford, R. W.; Guo, F.; Kaszynski, P. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 2327–2333. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2005.01.023 |

| 15. | Katritzky, A. R.; Barczynski, P.; Musumarra, G.; Pisano, D.; Szafran, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7–15. doi:10.1021/ja00183a002 |

| 1. | Norez, C.; Bilan, F.; Kitzis, A.; Mettey, Y.; Becq, F. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 325, 89–99. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.134502 |

| 2. | Roomans, G. M. Am. J. Respir. Med. 2003, 2, 413–431. doi:10.1007/BF03256668 |

| 3. | Prost, A.-L.; Dérand, R.; Gros, L.; Becq, F.; Vivaudou, M. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 66, 425–430. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00289-2 |

| 4. | Galietta, L. J. V.; Springsteel, M. F.; Eda, M.; Niedzinski, E. J.; By, K.; Haddadin, M. J.; Kurth, M. J.; Nantz, M. H.; Verkman, A. S. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 19723–19728. doi:10.1074/jbc.M101892200 |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 12. | García-Amorós, J.; Velasco, D. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 1003–1017. doi:10.3762/bjoc.8.113 |

| 5. | Sinan, M.; Panda, M.; Ghosh, A.; Dhara, K.; Fanwick, P. E.; Chattopadhyay, D. J.; Goswami, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5185–5193. doi:10.1021/ja710211u |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 6. | Garza-Ortiz, A.; den Dulk, H.; Brouwer, J.; Kooijman, H.; Spek, A. L.; Reedijk, J. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007, 101, 1922–1930. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.05.008 |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 5. | Sinan, M.; Panda, M.; Ghosh, A.; Dhara, K.; Fanwick, P. E.; Chattopadhyay, D. J.; Goswami, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5185–5193. doi:10.1021/ja710211u |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 9. | Carroll, W. A.; Altenbach, R. J.; Bai, H.; Brioni, J. D.; Brune, M. E.; Buckner, S. A.; Cassidy, C.; Chen, Y.; Coghlan, M. J.; Daza, A. V.; Drizin, I.; Fey, T. A.; Fitzgerald, M.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Gregg, R. J.; Henry, R. F.; Holladay, M. W.; King, L. L.; Kort, M. E.; Kym, P. R.; Milicic, I.; Tang, R.; Turner, S. C.; Whiteaker, K. L.; Yi, L.; Zhang, H.; Sullivan, J. P. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 3163–3179. doi:10.1021/jm030356w |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 19. | Foresman, J. B.; Keith, T. A.; Wiberg, K. B.; Snoonian, J.; Frisch, M. J. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 16098–16104. doi:10.1021/jp960488j |

| 8. | Taylor, E. C.; Tseng, C. P.; Rampal, J. B. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 552–555. doi:10.1021/jo00342a035 |

| 11. | Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Jankowiak, A.; Young, V. G. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 1339–1348. doi:10.1016/j.poly.2011.02.023 |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 17. | Scott, A. P.; Radom, L. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 16502–16513. doi:10.1021/jp960976r |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 7. | Jankowiak, A.; Obijalska, E.; Kaszynski, P.; Pieczonka, A.; Young, V. G., Jr. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3317–3327. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.023 |

| 10. | Campbell, N.; Henderson, A. W.; Taylor, D. J. Chem. Soc. 1953, 1281–1285. doi:10.1039/jr9530001281 |

| 18. | Peng, C.; Ayala, P. Y.; Schlegel, H. B.; Frisch, M. J. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 49–56. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19960115)17:1<49::AID-JCC5>3.3.CO;2-# |

© 2013 Jankowiak et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)