Abstract

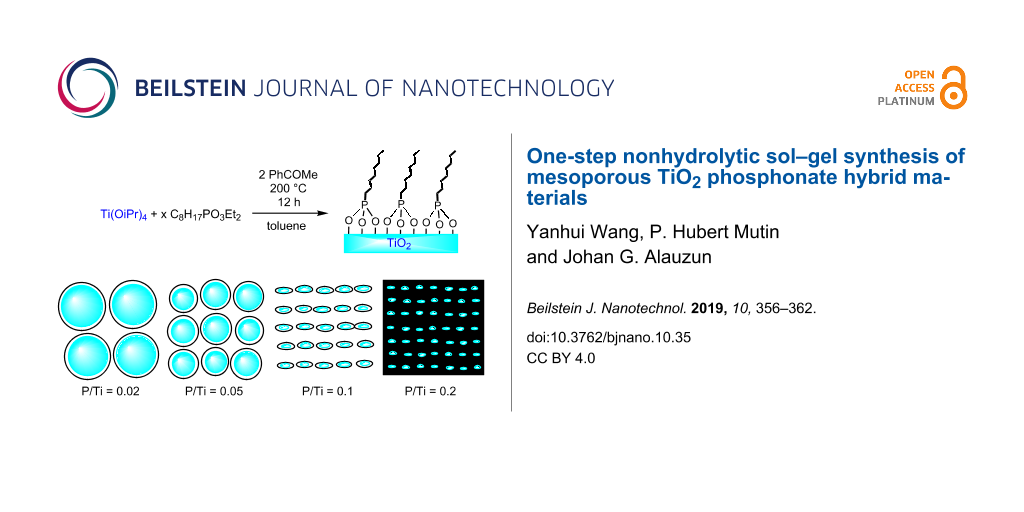

Mesoporous TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials were prepared in one step by a nonhydrolytic sol–gel method involving the reaction of Ti(OiPr)4, acetophenone (2 equiv) and diethyl octylphosphonate (from 0 to 0.2 equiv) at 200 °C for 12 hours, in toluene. The different samples were characterized by 31P magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and nitrogen physisorption. For P/Ti ratios up to 0.1, the hybrid materials can be described as aggregated, roughly spherical, crystalline anatase nanoparticles grafted by octylphosphonate groups via Ti–O–P bonds. The crystallite size decreases with the P/Ti ratio, leading to an increase of the specific surface area and a decrease of the pore size of the hybrid samples. For a P/Ti ratio of 0.2, the volume fraction of organic octyl groups exceeds 50%. The hybrid material becomes nonporous and can be described as amorphous TiO2 clusters modified by octylphosphonate units, where the octyl chains form an organic continuous matrix.

Introduction

The development of porous hybrid organic–inorganic materials has been a major goal for materials scientists for more than 25 years [1-3]. Combining inorganic and organic moieties at the nanoscale allows the design of tailor-made functional materials with enhanced or new properties, adapted to a wide range of advanced applications [4-7]. In Class I hybrid materials, the inorganic and organic parts are linked through weak bonds (e.g., van der Waals or hydrogen bonds), while in Class II hybrid materials, they are linked by stronger ionocovalent or covalent bonds [8].

The majority of Class II hybrid materials utilize the stability of the Si–C bond and are based on organosilsesquioxane (R–SiO1.5) or bridged organosilsesquioxane (O1.5Si–R–O1.5). These hybrids are usually prepared by conventional sol–gel processing, i.e., by hydrolysis and condensation of alkoxysilane precursors, which offers an excellent control over composition and homogeneity, while texture can be tuned using various templating approaches [9].

In the case of metals, as M–C bonds are (in most cases) quite unstable, the organic groups can be linked to the metal oxide network via carboxylate or β-diketonate ligands [5,10,11]. Organophosphorus ligands such as phosphonates appear quite promising as they form strong ionocovalent M–O–P bonds with many metals, as shown by the numerous examples of metal phosphonates reported in the literature [12-14]. However, in the case of monophosphonate groups, metal phosphonates usually form semicrystalline layered materials with no interlayer porosity. A way to avoid the formation of a layered material is to use an excess of metal precursor in order to form a metal oxide–phosphonate hybrid material. There are very few examples of the preparation of such materials by sol–gel methods [15,16], and the texture of these materials has not been reported. Actually, most metal oxide–phosphonate-based porous hybrids are obtained in two steps, by surface modification of a porous metal oxide support [17-19].

Nonhydrolytic (or nonaqueous) sol–gel (NHSG) chemistry has provided simple and powerful routes to synthesize oxides or mixed oxides with different morphologies (e.g., nanoparticles) or textures (e.g., mesoporous materials) [20-24]. Several NHSG routes have also been used to prepare Class II hybrids. For instance the alkyl elimination route was applied to the synthesis of organosilsesquioxanes, organosilsesquioxane–metal oxide hybrids [25-27], silica–titania modified by organosilicon groups [28,29], and metal phosphonates [30]. More recently, hybrid silicophosphate xerogels have been produced by reaction of acetoxysilanes with trimethylsilyl esters of phosphoric or phosphonic acids [31], and porous organosilicate covalent polymers have been synthesized by reaction of silicon acetate with 1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene [32].

The reaction of alkoxides in acetophenone (used as a solvent and an oxygen donor) has already been described for the synthesis of TiO2 [33] and BaTiO3 [34] nanoparticles, but it has never been used to prepare mesoporous oxides or hybrid materials.

In the present work, we present an original one-step NHSG synthesis of mesoporous TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials, using a nonhydrolytic sol–gel method involving the reaction of titanium tetraisopropoxide and diethyl octylphosphonate precursors at 200 °C in the presence of acetophenone as an oxygen donor.

Results

A series of TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrids was synthesized by reaction of Ti(OiPr)4 (1 equiv) with different amounts of diethyl octylphosphonate (0.02, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 equiv) and acetophenone (2 equiv) at 200 °C. It must be mentioned that, in the absence of acetophenone, diethyl octylphosphonate did not react with titanium tetraisopropoxide under the same conditions. All four materials are referred to as TiPx where x is the P/Ti ratio. For comparison, a TiO2 sample was prepared under the exact same conditions but without diethyl octylphosphonate.

Elemental analysis by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) of these materials showed that in all cases the measured P/Ti ratios were close to the nominal ones, indicating that all the octylphosphonate units were incorporated in the materials (Table 1).

Table 1: Elemental analysis, crystallite size and textural data for TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrids and TiO2.

| Sample | P/Ti ratioa | Cryst. sizeb (nm) | SBETc (m2 g−1) | Vpd (cm3 g−1) | Dpe (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | NA | 9 | 120 | 0.35 | 9.7 |

| TiP0.02 | 0.023 | 16 | 120 | 0.29 | 8.0 |

| TiP0.05 | 0.054 | 11 | 160 | 0.23 | 4.5 |

| TiP0.1 | 0.096 | 6 | 240 | 0.17 | 3.1 |

| TiP0.2 | 0.192 | NA | <10 | <0.01 | NA |

aP/Ti ratio determined by EDX; bcrystallite size determined by the Scherrer equation for the (101) reflection; cspecific surface area, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method; dtotal pore volume at P/P0 = 0.990; eBarrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) average pore diameter calculated from the desorption branch. NA: not applicable. 31P solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a useful tool for studying phosphonate-based hybrid materials: it gives information on the presence of phosphonate units bonded to the oxide nework, on the presence of a metal phosphonate phase or of "free" phosphonate precursor (e.g., excess precursor, physisorbed or trapped molecules), but it is not possible to ascribe the different components found in the 31P NMR spectrum to the different bonding modes (mono-, bi-, and tridentate phosphonate units) [35].

The 31P solid-state NMR spectra of the hybrid materials (Figure 1) display a very broad signal in the 10 to 35 ppm range. Similar broad resonances have been reported for TiO2–phenylphosphonate hybrid materials prepared in a two-step sol–gel process from Ti(OiPr)4 and PhPO3H2 [15], whereas the hybrid materials obtained by surface modification of anatase supports usually show narrower resonances [36]. These spectra confirm the presence of phosphonate species linked to the TiO2 network through Ti–O–P bonds, and show the absence of a layered titanium octylphosphonate phase, which would lead to a sharp resonance at 7 ppm. In the case of the TiP0.2 sample, the shoulder at 31 ppm suggests the presence of a small amount of noncondensed diethyl octylphosphonate precursor, possibly molecules trapped in the network of this nonporous sample (see below).

![[2190-4286-10-35-1]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-10-35-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: 31P CP magic angle spinning solid-state NMR spectra of the hybrid materials produced by the reaction of octylphosphonate, Ti(OiPr)4 and acetophenone (TiO2-octylphosphonate hybrids).

Figure 1: 31P CP magic angle spinning solid-state NMR spectra of the hybrid materials produced by the reactio...

The attenuated total reflection (ATR)-Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials (Figure 2) showed a single broad vibration between 900 and 1200 cm−1 arising from vibration modes of the CPO3 tetrahedra. The intensity of this band increases with the P/Ti ratio. The absence of bands at ≈1220 cm−1 (P=O stretching vibration) and ≈950 cm−1 (P–OC stretching vibrations) [36] suggests that most of the phosphonate groups are in the same tridentate environment as in layered titanium phosphonates, that is, bonded to three Ti atoms in CP(OTi)3 sites, as previously reported for sol–gel TiO2–phenylphosphonate hybrid materials [15]. The vibrations in the 1400–1500 cm−1 range can be ascribed to CH3 and CH2 deformations of groups in residual surface moieties (e.g., Ti–OiPr, Ti–O–CMePhOiPr), and to CH3, CH2 and P–CH2 deformations in the octylphosphonate groups. The three bands between 2800 and 3000 cm−1 are ascribed to the C–H symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of bonds in CH2 and CH3, mostly in the octyl groups, as shown by the intensity of these bands which is directly related to the P/Ti ratio. The weak, broad band between 3000 and 3800 cm−1 is characteristic of O–H stretching vibrations. This band indicates the presence of a low amount of adsorbed water (confirmed by the vibration at 1620 cm−1 assigned to a deformation mode of adsorbed water), and also of surface hydroxyl groups resulting from the hydrolysis of residual surface groups during washing or manipulation under air.

![[2190-4286-10-35-2]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-10-35-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: ATR-FTIR spectra of the TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials.

Figure 2: ATR-FTIR spectra of the TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of TiO2 and of the hybrid samples are presented in Figure 3. The patterns of TiP0.02 and TiP0.05 showed the presence of well-crystallized anatase nanocrystals (JCPDS 21-1272), as in the TiO2 sample. There was no evidence of rutile. The TiP0.1 sample appeared partially crystallized, while the TiP0.2 sample was amorphous in XRD experiments. The crystallite size (Table 1) of the hybrid samples decreased with the P/Ti ratio from 16 to 6 nm. The lower intensity of the (004) reflection compared to the (200) reflection indicated that the crystallites are not elongated and have a roughly spherical morphology.

![[2190-4286-10-35-3]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-10-35-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Powder XRD patterns of the TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials.

Figure 3: Powder XRD patterns of the TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials.

Raman spectroscopy (Figure 4) confirmed the XRD results. For P/Ti ratios between 0 and 0.05, the spectra showed a strong peak at 145 cm−1 and smaller peaks at 195, 400, 515 and 640 cm−1 indicating the presence of anatase. The spectrum of TiP0.1 showed broader and weaker bands, and the first band was shifted to 148 cm−1. Under the same conditions, no bands could be observed in the spectrum of TiP0.2, indicating highly disordered TiO2 domains.

![[2190-4286-10-35-4]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-10-35-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Raman spectra of TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials and TiO2.

Figure 4: Raman spectra of TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials and TiO2.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the TiO2 sample and of the TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials are displayed in Figure 5. The morphology of the samples did not significantly depend on the P/Ti ratio: all samples appeared to be formed of densely aggregated, roughly spherical, nanoparticles. For P/Ti ratios of 0.1 and 0.2, the particles were smaller and formed denser aggregates than for lower P/Ti ratios.

![[2190-4286-10-35-5]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-10-35-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: SEM images of TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials and TiO2.

Figure 5: SEM images of TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials and TiO2.

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of the different samples are displayed in Figure 6, except for the TiP0.2 sample which was nonporous with a negligible specific surface area. All other samples showed significant porosity. Their specific surface area increased with the P/Ti ratio, from 120 m2 g−1 for TiP0.02 to 240 m2 g−1 for TiP0.1, while their pore volume decreased, from 0.29 to 0.17 cm3 g−1 (Table 1). Interestingly, the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) C constant, which is related to the adsorption enthalpy, decreased with the P/Ti ratio (42 for TiP0.02, 36 for TiP0.05, 28 for TiP0.1), as previously reported for nanoparticles grafted by octylphosphonic acid [37]. According to the recent IUPAC classification, the isotherms of TiO2 and of the hybrid samples are mainly of type IVa, characteristic of mesoporous adsorbents, with an H2 hysteresis loop indicating complex pore structures [38]. The TiP0.02 and TiP0.05 isotherms also showed Type II features (lack of plateau at high relative pressure) suggesting the presence of some macropores. As SEM images do not show the presence of macropores in TiP0.05 and TiP0.02 samples, these macropores likely correspond to pores between relatively small aggregates resulting from the grinding of the samples. The pore size distribution results confirmed the presence of mesopores in all samples (except the nonporous TiP0.2 sample). The sharp peak found in the distribution for TiP0.1 at ≈4 nm is a well-known artefact related to the instability of the meniscus at relative pressures lower than 0.42; it simply indicates the presence of small pores of diameter <4 nm. The average mesopore diameter decreased when the P/Ti ratio increased, from 8.0 nm for TiP0.02 to 3.1 nm for TiP0.1 (Table 1).

![[2190-4286-10-35-6]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-10-35-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: N2 physisorption isotherms at 77 K (left) and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) mesopore size distribution (desorption branch, right) of TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials and TiO2. Open and filled symbols in the isotherms refer to adsorption and desorption, respectively.

Figure 6: N2 physisorption isotherms at 77 K (left) and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) mesopore size distributi...

Discussion and Conclusion

The reaction at 200 °C of diethyl octylphosphonate and Ti(OiPr)4 in the presence of acetophenone provides a simple and original method to prepare TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrid materials in one step (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Ideal reaction scheme and hypothetical structures of the obtained hybrid materials.

Scheme 1: Ideal reaction scheme and hypothetical structures of the obtained hybrid materials.

The different characterization methods allow us to better understand the structure of these hybrid materials. The presence of even a relatively small amount of phosphonate units strongly influences the size and crystallinity of the TiO2 domains.

For P/Ti ratios up to 0.1, the hybrid materials can be described as rounded anatase nanoparticles grafted by octylphosphonate groups via Ti–O–P bonds. This is a major advantage of the present nonhydrolytic sol-gel method: previous attempts to prepare such TiO2–phosphonate hybrids by hydrolytic sol–gel routes led to amorphous TiO2 domains [15,39].

The low values found for the BET C constant (from 42 for TiP0.02 to 28 for TiP0.1) confirm that the surface of the anatase nanoparticles is capped by apolar octyl groups. C values of 47 and 34 have been reported for oxide nanoparticles post-modified by octylphosphonic acid with grafting densities of 1.4 and 4.1 P/nm2, respectively [37]. In our hybrid materials, the anatase particle size decreases with the P/Ti ratio, leading to an increase of the specific surface area of the crystallites. The density of grafting, estimated from the composition and from the diameter of the crystallites (assuming a spherical shape and a density of 3.8), increases with the P/Ti ratio from 1.5 P/nm2 for TiP0.02 to 2.9 P/nm2 for TiP0.1. These values suggest the formation of monolayers with low to moderate density (grafting densities of up to 4 to 5 P/nm2 have been reported for well-ordered self-assembled monolayers). The mesoporosity of the hybrid materials with P/Ti ratios up to 0.1 stems from the aggregation of the grafted nanoparticles (interparticle porosity). The smaller the size of the particles, the higher the specific surface area and the lower the pore volume (Scheme 1).

For a P/Ti ratio of 0.2, the TiO2 domains are completely amorphous, probably because they involve very few Ti atoms. In this case the volume fraction of the octyl groups exceeds 50%. The diameter of the TiO2 domains and the length of octyl chains are in the same order of magnitude, and the lack of porosity of this sample likely results from the interdigitation or mixing of the alkyl chains.

These mesoporous metal oxide–phosphonate materials can be seen as a low-cost alternative to periodic mesoporous organosilicas (PMOs) and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) for applications in the field of heterogeneous catalysis or selective adsorption. Their high hydrolytic stability over a wide range of pH [15] and the possibility to functionalize them with a variety of functional groups makes them particularly promising for applications in aqueous phase catalysis (e.g., for biomass conversion) and in aqueous wastewater treatment.

Experimental

Titanium(IV) isopropoxide (Ti(OiPr)4, 97 %), and acetophenone (99%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Diethyl 1-octylphosphonate (C8H17PO3Et2, 98%) was purchased from Sikémia. Toluene was dried over a Pure-Solve MD5 solvent purification system (H2O <10 ppm, controlled with a Karl Fischer coulometer). All other chemicals were used without further purification. All manipulations were carried out in a glove box under argon atmosphere (<5 ppm of water and O2).

Synthesis of TiO2–octylphosphonate hybrids

In a typical preparation, Ti(OiPr)4 (1.72 g, 6.00 mmol), acetophenone (1.44 g, 12.00 mmol), C8H17PO3Et2 (0 mmol, 0.24 mmol, 0.60 mmol, 1.20 mmol, or 2.40 mmol) and toluene (8.0 mL) were mixed in a stainless steel digestion vessel with a PTFE lining (23 mL). The sealed autoclave was heated in an oven at 200 °C for 12 h under autogenous pressure. After reaction, the resulting monoliths were thoroughly washed with acetone (5 times, 30 mL). Then, they were dried under reduced pressure (5.10−2 mbar) at room temperature and ground into a fine powder.

Characterization

FTIR spectra were collected in ATR mode on a Spectrum II spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer). The powder XRD patterns were collected with a PANalytical X’Pert Pro MPD diffractometer (Cu Kα1 = 0.1540598 nm). The SEM images were obtained with a Hitachi S-4800 electron microscope. EDX was done on an Oxford Instruments X-MaxN SDD instrument. Nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms were measured at 77 K with a Micrometrics TriStar 3000 apparatus; the specific surface area was determined by the BET method in the 0.05–0.25 P/P0 range. The mesopore volume and pore size distribution were obtained by the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method from the desorption branch.

Solid-state 31P magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR experiments were performed on a Varian VNMRS 400 MHz (9.4 T) spectrometer using a 3.2 mm Varian T3 HXY MAS probe. Single pulse experiments were carried out with a spinning rate of 20 kHz, a 90° excitation pulse of 3 μs, a recycle delay of 30 s and 100 kHz spinal-64 1H decoupling. 200 transients were recorded. The 31P chemical shift was determined using an external reference, hydroxyapatite Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, at 2.8 ppm (with respect to H3PO4, 85 wt % in water).

References

-

Sanchez, C.; Ribot, F. New J. Chem. 1994, 18, 1007–1047.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sanchez, C.; Shea, K. J.; Kitagawa, S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 471–472. doi:10.1039/c1cs90001c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kickelbick, G. Introduction to Hybrid Materials; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co: Weinheim, Germany, 2007. doi:10.1002/9783527610495.ch1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Drisko, G. L.; Sanchez, C. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 5097–5105. doi:10.1002/ejic.201201216

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nicole, L.; Laberty-Robert, C.; Rozes, L.; Sanchez, C. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 6267–6292. doi:10.1039/c4nr01788a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Parola, S.; Julián-López, B.; Carlos, L. D.; Sanchez, C. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 6506–6544. doi:10.1002/adfm.201602730

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Santos, L. D.; Maréchal, M.; Guillermo, A.; Lyonnard, S.; Moldovan, S.; Ersen, O.; Sel, O.; Perrot, H.; Laberty-Robert, C. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 594–604. doi:10.1002/adfm.201504076

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Judeinstein, P.; Sanchez, C. J. Mater. Chem. 1996, 6, 511–525. doi:10.1039/jm9960600511

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hoffmann, F.; Cornelius, M.; Morell, J.; Fröba, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3216–3251. doi:10.1002/anie.200503075

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schubert, U. J. Mater. Chem. 2005, 15, 3701–3715. doi:10.1039/b504269k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schubert, U. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 730–737. doi:10.1021/ar600036x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Clearfield, A. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2002, 6, 495–506. doi:10.1016/s1359-0286(02)00151-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gagnon, K. J.; Perry, H. P.; Clearfield, A. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1034–1054. doi:10.1021/cr2002257

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Clearfield, A. The early history and growth of metal phosphonate chemistry. In Metal Phosphonate Chemistry: From Synthesis to Applications; Clearfield, A.; Demadis, K., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2011; pp 1–44. doi:10.1039/9781849733571-00001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 1268–1272. doi:10.1021/cm991125+

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Maillet, C.; Janvier, P.; Bertrand, M.-J.; Praveen, T.; Bujoli, B. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 1685–1689. doi:10.1002/1099-0690(200205)2002:10<1685::aid-ejoc1685>3.0.co;2-i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mutin, P. H.; Guerrero, G.; Vioux, A. J. Mater. Chem. 2005, 15, 3761–3768. doi:10.1039/b505422b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guerrero, G.; Alauzun, J. G.; Granier, M.; Laurencin, D.; Mutin, P. H. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 12569–12585. doi:10.1039/c3dt51193f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Queffélec, C.; Petit, M.; Janvier, P.; Knight, D. A.; Bujoli, B. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3777–3807. doi:10.1021/cr2004212

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 582–596. doi:10.1021/cm802348c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Debecker, D. P.; Hulea, V.; Mutin, P. H. Appl. Catal., A 2013, 451, 192–206. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2012.11.002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pinna, N.; Niederberger, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5292–5304. doi:10.1002/anie.200704541

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deshmukh, R.; Niederberger, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 8542–8570. doi:10.1002/chem.201605957

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Styskalik, A.; Skoda, D.; Barnes, C.; Pinkas, J. Catalysts 2017, 7, 168. doi:10.3390/catal7060168

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bourget, L.; Leclercq, D.; Vioux, A. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 1999, 14, 137–147. doi:10.1023/a:1008729832145

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Crouzet, L.; Leclercq, D.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 1530–1534. doi:10.1021/cm020985e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hay, J. N.; Raval, H. M. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 3396–3403. doi:10.1021/cm011024n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Smeets, V.; Ben Mustapha, L.; Schnee, J.; Gaigneaux, E. M.; Debecker, D. P. Mol. Catal. 2018, 452, 123–128. doi:10.1016/j.mcat.2018.04.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lorret, O.; Lafond, V.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 4707–4709. doi:10.1021/cm061478q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Corriu, R. J. P.; Leclercq, D.; Mutin, P. H.; Sarlin, L.; Vioux, A. J. Mater. Chem. 1998, 8, 1827–1833. doi:10.1039/a803755h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Styskalik, A.; Skoda, D.; Moravec, Z.; Babiak, M.; Barnes, C. E.; Pinkas, J. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 7477–7487. doi:10.1039/c4ta06823h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kejik, M.; Moravec, Z.; Barnes, C. E.; Pinkas, J. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 240, 205–215. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.11.012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Garnweitner, G.; Antonietti, M.; Niederberger, M. Chem. Commun. 2005, 397–399. doi:10.1039/b414510k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pazik, R.; Tekoriute, R.; Håkansson, S.; Wiglusz, R.; Strek, W.; Seisenbaeva, G. A.; Gun'ko, Y. K.; Kessler, V. G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 6820–6826. doi:10.1002/chem.200900836

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brodard-Severac, F.; Guerrero, G.; Maquet, J.; Florian, P.; Gervais, C.; Mutin, P. H. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 5191–5196. doi:10.1021/cm8012683

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 4367–4373. doi:10.1021/cm001253u

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lassiaz, S.; Labarre, D.; Galarneau, A.; Brunel, D.; Mutin, P. H. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 8199–8205. doi:10.1039/c1jm10128e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J. P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K. S. W. Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051. doi:10.1515/pac-2014-1117

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maillet, C.; Janvier, P.; Pipelier, M.; Praveen, T.; Andres, Y.; Bujoli, B. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 2879–2884. doi:10.1021/cm010123y

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Sanchez, C.; Ribot, F. New J. Chem. 1994, 18, 1007–1047. |

| 2. | Sanchez, C.; Shea, K. J.; Kitagawa, S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 471–472. doi:10.1039/c1cs90001c |

| 3. | Kickelbick, G. Introduction to Hybrid Materials; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co: Weinheim, Germany, 2007. doi:10.1002/9783527610495.ch1 |

| 5. | Nicole, L.; Laberty-Robert, C.; Rozes, L.; Sanchez, C. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 6267–6292. doi:10.1039/c4nr01788a |

| 10. | Schubert, U. J. Mater. Chem. 2005, 15, 3701–3715. doi:10.1039/b504269k |

| 11. | Schubert, U. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 730–737. doi:10.1021/ar600036x |

| 33. | Garnweitner, G.; Antonietti, M.; Niederberger, M. Chem. Commun. 2005, 397–399. doi:10.1039/b414510k |

| 9. | Hoffmann, F.; Cornelius, M.; Morell, J.; Fröba, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3216–3251. doi:10.1002/anie.200503075 |

| 34. | Pazik, R.; Tekoriute, R.; Håkansson, S.; Wiglusz, R.; Strek, W.; Seisenbaeva, G. A.; Gun'ko, Y. K.; Kessler, V. G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 6820–6826. doi:10.1002/chem.200900836 |

| 8. | Judeinstein, P.; Sanchez, C. J. Mater. Chem. 1996, 6, 511–525. doi:10.1039/jm9960600511 |

| 31. | Styskalik, A.; Skoda, D.; Moravec, Z.; Babiak, M.; Barnes, C. E.; Pinkas, J. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 7477–7487. doi:10.1039/c4ta06823h |

| 4. | Drisko, G. L.; Sanchez, C. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 5097–5105. doi:10.1002/ejic.201201216 |

| 5. | Nicole, L.; Laberty-Robert, C.; Rozes, L.; Sanchez, C. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 6267–6292. doi:10.1039/c4nr01788a |

| 6. | Parola, S.; Julián-López, B.; Carlos, L. D.; Sanchez, C. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 6506–6544. doi:10.1002/adfm.201602730 |

| 7. | Santos, L. D.; Maréchal, M.; Guillermo, A.; Lyonnard, S.; Moldovan, S.; Ersen, O.; Sel, O.; Perrot, H.; Laberty-Robert, C. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 594–604. doi:10.1002/adfm.201504076 |

| 32. | Kejik, M.; Moravec, Z.; Barnes, C. E.; Pinkas, J. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 240, 205–215. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.11.012 |

| 20. | Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 582–596. doi:10.1021/cm802348c |

| 21. | Debecker, D. P.; Hulea, V.; Mutin, P. H. Appl. Catal., A 2013, 451, 192–206. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2012.11.002 |

| 22. | Pinna, N.; Niederberger, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5292–5304. doi:10.1002/anie.200704541 |

| 23. | Deshmukh, R.; Niederberger, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 8542–8570. doi:10.1002/chem.201605957 |

| 24. | Styskalik, A.; Skoda, D.; Barnes, C.; Pinkas, J. Catalysts 2017, 7, 168. doi:10.3390/catal7060168 |

| 28. | Smeets, V.; Ben Mustapha, L.; Schnee, J.; Gaigneaux, E. M.; Debecker, D. P. Mol. Catal. 2018, 452, 123–128. doi:10.1016/j.mcat.2018.04.011 |

| 29. | Lorret, O.; Lafond, V.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 4707–4709. doi:10.1021/cm061478q |

| 17. | Mutin, P. H.; Guerrero, G.; Vioux, A. J. Mater. Chem. 2005, 15, 3761–3768. doi:10.1039/b505422b |

| 18. | Guerrero, G.; Alauzun, J. G.; Granier, M.; Laurencin, D.; Mutin, P. H. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 12569–12585. doi:10.1039/c3dt51193f |

| 19. | Queffélec, C.; Petit, M.; Janvier, P.; Knight, D. A.; Bujoli, B. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3777–3807. doi:10.1021/cr2004212 |

| 30. | Corriu, R. J. P.; Leclercq, D.; Mutin, P. H.; Sarlin, L.; Vioux, A. J. Mater. Chem. 1998, 8, 1827–1833. doi:10.1039/a803755h |

| 15. | Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 1268–1272. doi:10.1021/cm991125+ |

| 16. | Maillet, C.; Janvier, P.; Bertrand, M.-J.; Praveen, T.; Bujoli, B. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 1685–1689. doi:10.1002/1099-0690(200205)2002:10<1685::aid-ejoc1685>3.0.co;2-i |

| 12. | Clearfield, A. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2002, 6, 495–506. doi:10.1016/s1359-0286(02)00151-1 |

| 13. | Gagnon, K. J.; Perry, H. P.; Clearfield, A. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1034–1054. doi:10.1021/cr2002257 |

| 14. | Clearfield, A. The early history and growth of metal phosphonate chemistry. In Metal Phosphonate Chemistry: From Synthesis to Applications; Clearfield, A.; Demadis, K., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2011; pp 1–44. doi:10.1039/9781849733571-00001 |

| 25. | Bourget, L.; Leclercq, D.; Vioux, A. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 1999, 14, 137–147. doi:10.1023/a:1008729832145 |

| 26. | Crouzet, L.; Leclercq, D.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 1530–1534. doi:10.1021/cm020985e |

| 27. | Hay, J. N.; Raval, H. M. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 3396–3403. doi:10.1021/cm011024n |

| 36. | Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 4367–4373. doi:10.1021/cm001253u |

| 35. | Brodard-Severac, F.; Guerrero, G.; Maquet, J.; Florian, P.; Gervais, C.; Mutin, P. H. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 5191–5196. doi:10.1021/cm8012683 |

| 15. | Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 1268–1272. doi:10.1021/cm991125+ |

| 15. | Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 1268–1272. doi:10.1021/cm991125+ |

| 15. | Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 1268–1272. doi:10.1021/cm991125+ |

| 39. | Maillet, C.; Janvier, P.; Pipelier, M.; Praveen, T.; Andres, Y.; Bujoli, B. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 2879–2884. doi:10.1021/cm010123y |

| 37. | Lassiaz, S.; Labarre, D.; Galarneau, A.; Brunel, D.; Mutin, P. H. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 8199–8205. doi:10.1039/c1jm10128e |

| 37. | Lassiaz, S.; Labarre, D.; Galarneau, A.; Brunel, D.; Mutin, P. H. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 8199–8205. doi:10.1039/c1jm10128e |

| 38. | Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J. P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K. S. W. Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051. doi:10.1515/pac-2014-1117 |

| 36. | Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 4367–4373. doi:10.1021/cm001253u |

| 15. | Guerrero, G.; Mutin, P. H.; Vioux, A. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 1268–1272. doi:10.1021/cm991125+ |

© 2019 Wang et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjnano)