Abstract

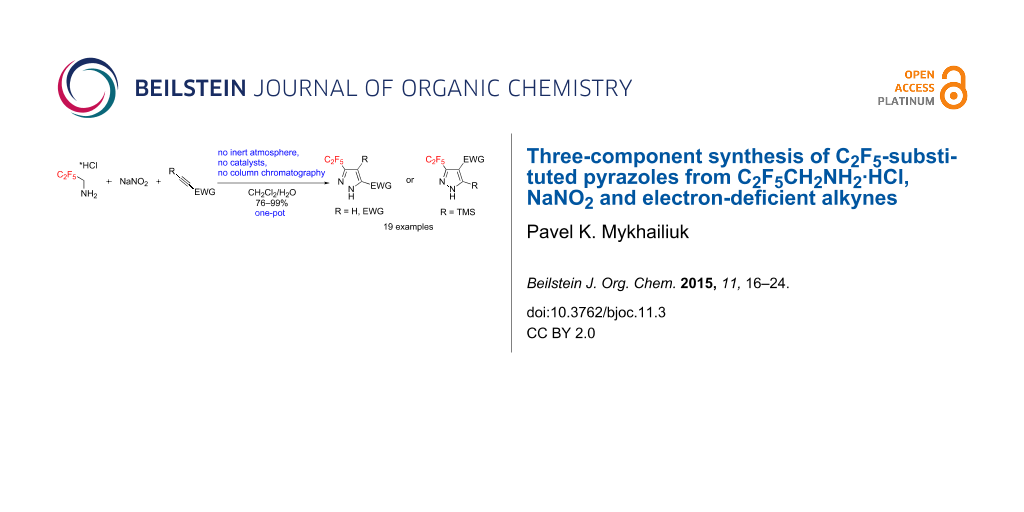

A one-pot reaction between C2F5CH2NH2·HCl, NaNO2 and electron-deficient alkynes gives C2F5-substituted pyrazoles in excellent yields. The transformation smoothly proceeds in dichloromethane/water, tolerates the presence of air, and requires no purification of products by column chromatography. Mechanistically, C2F5CH2NH2·HCl and NaNO2 react first in water to generate C2F5CHN2, that participates in a [3 + 2] cycloaddition with electron-deficient alkynes in dichloromethane.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Incorporation of fluorinated fragments into organic compounds might affect their physicochemical and biological properties [1-8]. It is not surprising, therefore, that up to 20% of all modern drugs contain at least one fluorine atom [9-11]. Fluorinated pyrazoles, for example, do play a role in medicinal chemistry: among them are inhibitors of the measles virus RNA polymerase complex [12], CRAC channel, cyclogenases [13-15], 5-lipoxygenase [16], heat shock protein 90 [17]; inducers of G0–G1 phase arrest [18], modulators of the AMPA receptor [19], activators of the Kv7/KCNQ potassium channel [20], regulators of the NFAT transcription factor [21], etc. Approved drugs and agrochemicals – Bixafen, Fipronyl, Celecoxib, Pyroxasulfone and Penflufen – are also pyrazoles with diverse fluorine-containing substituents (Figure 1) [22,23]. Moreover, fluorinated NH-pyrazoles have also found an application as ligands in coordinational chemistry [24-27].

Figure 1: Bioactive compounds and agrochemicals with fluorinated pyrazoles.

Figure 1: Bioactive compounds and agrochemicals with fluorinated pyrazoles.

While the trifluoromethylated derivatives play a major role in chemistry [28], their more lipophilic analogues – C2F5 [1,29,30] and SF5 [1,31] – only gain popularity. The C2F5-substituted derivatives, for example, often have higher activity compared with the CF3-counterparts [32,33]. Therefore, some bioactive compounds including several drugs contain a C2F5 group (Figure 2) [34-36].

Figure 2: Bioactive compounds with C2F5 group [34-36].

Figure 2: Bioactive compounds with C2F5 group [34-36].

The conceptually attractive C2F5-pyrazoles [37], however, still remain somewhat in the shadow [38], probably because of the lack of the corresponding chemical approaches. Predominantly, C2F5-pyrazoles are synthesized by a reaction of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds (or their synthons) with hydrazines [39-44]. In this context, novel practical methods to C2F5-pyrazoles are needed.

Last year, Ma and colleagues synthesized CF3-pyrazoles by [3 + 2] cycloaddition between in situ generated CF3CHN2 and alkynes [45]. This method, however, required a) the preliminary preparation of a dry solution of toxic CF3CHN2; b) the use of inert atmosphere; c) an addition of a catalyst (Ag2O); and d) purification of products by column chromatography. Also, the reaction worked only for mono-substituted alkynes. In parallel, an alternative practical approach to CF3-pyrazoles by a three-component reaction between electron-deficient alkynes, sodium nitrite and trifluoroethylamine hydrochloride was developed [46]. This method worked for both the mono- and disubstituted alkynes. Because of similar electronic properties of CF3 and C2F5 groups [1], it was supposed that a reaction between in situ generated C2F5CHN2 [47], and electron-deficient alkynes would lead to C2F5-pyrazoles. In this work, this hypothesis was proven; the scope and selectivity of this transformation was studied and the high practical potential of the developed method is shown.

Results and Discussion

Validation and optimization

To challenge the putative transformation, the simple mono-substituted alkyne 1 with one electron-withdrawing CO2Me-group (EWG) was selected. A mixture of alkyne 1, C2F5CH2NH2·HCl (1.0 equiv) [48] and NaNO2 (2.0 equiv) in water/dichloromethane was stirred at room temperature. After 10 min the organic layer became yellow indicating the formation of C2F5CHN2. After 24 h the reaction conversion was 55%, but no side products were observed. Optimization of the reaction conditions – C2F5CH2NH2·HCl (3.0 equiv), NaNO2 (5.0 equiv), 72 h – allowed achieving the full reaction conversion (Table 1, entry 6). The standard work-up afforded pyrazole 1a as a white crystalline solid in 99% yield without any purification (neither recrystallization, nor column chromatography). The reaction required no inert gas atmosphere, and was performed in air.

Reaction scope

Having these encouraging results on pyrazole 1a at hand, the reaction scope was studied. First, various mono-substituted alkynes 2–14 were tested under the already optimized reaction conditions (Table 2).

Table 2: Synthesis of C2F5-substituted pyrazoles from mono-substituted alkynes.

|

|

||||||

| Entry | Alkyne | Product | Yield (%)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

|

1a |

|

99 | |

| 2 | 2 |

|

2a |

|

98 | |

| 3 | 3 |

|

3a |

|

97 | |

| 4 | 4 |

|

4a |

|

59 (76)b

78c |

|

| 5 | 5 |

|

5a |

|

22 (55)b

88c |

|

| 6 | 6 |

|

6a |

|

99 | |

| 7 | 7 |

|

7a |

|

98 | |

| 8 | 8 |

|

8a |

|

97 | |

| 9 | 9 |

|

9a |

|

95 | |

| 10 | 10 |

|

10a |

|

23 (33)b

45c X-ray |

|

| 11 | 11 |

|

11a |

|

57d | |

| 12 | 12 |

|

12a |

|

38d | |

| 13 | 13 |

|

no reaction | –b,c | ||

| 14 | 14 |

|

no reaction | –b,c | ||

aIsolated yields. brt, 168 h, dichloromethane/water. The reaction conversion is in brackets: ( ). c45 °C, 72 h, toluene/water. d40 °C, 72 h, dichloromethane/water.

Substrates 2, 3, 6–9 with strong EWGs smoothly reacted with C2F5CHN2 at room temperature to afford products 2a, 3a, 6a–9a in excellent yields of 95–99% without any purification. Substrates 4, 5 and 10–12 with weak EWG reacted slowly, and even after one week the reaction was not complete (33–76% conversion). The pure products 4a, 5a, and 10a–12a (Table 2) were obtained in bad yields after crystallization of the reaction mixtures. For these compounds, however, the yields were improved to 38–88% by performing the reaction at increased temperature: 40–45 °C.

This method, however, did not work for aromatic alkynes with either weak EWG (13) or electron-donating group (EDG, 14) – all attempts to react substrates 13 and 14 failed. These results suggest that the reaction between C2F5CHN2 and alkynes belongs to type I of [3 + 2] cycloadditions [49]: It is accelerated by the alkyne`s EWGs and decelerated by EDGs.

Next diverse disubstituted alkynes 15–22 (Table 3) with at least one strong EWG (–CO2Alk or –COAlk) were studied. Substrates 15–18 with the second EWG smoothly reacted with C2F5CHN2 to afford pyrazoles in almost quantitative yield. Substrate 19 with the second EDG (SiMe3), however, reacted slowly. The reaction conversion was 52% after 7 days leading to the sole regioisomer 19b without side products. The crystalline product 19b was purified from the liquid starting material by washing with cyclohexane. The yield of 19b was improved to 73% by performing the reaction at 40 °C (Table 3, entry 5). SiMe3-substituted substrates 20, 21 also reacted slowly, but again performing the reaction at 40 °C allowed to obtain the target products 20b, 21a/b in good yields. Substrate 22 with the second EDG – aryl – did not react, however.

Table 3: Synthesis of C2F5-substituted pyrazoles from disubstituted alkynes.

|

|

||||||

| Entry | Alkyne | Product | Yield (%)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 |

|

15a |

|

99 | |

| 2 | 16 |

|

16a |

|

98 | |

| 3 | 17 |

|

17a |

|

65 | |

| 4 | 18 |

|

18a/b

(2.6/1.0) |

|

99b | |

| 5 | 19 |

|

19b |

|

43 (52)c

73d X-ray |

|

| 6 | 20 |

|

20b/a

(4.0/1.0) |

|

62e X-ray | |

| 7 | 21 |

|

21b/a

(2.6/1.0) |

|

89b | |

| 8 | 22 |

|

no reactionc,d | |||

aIsolated yields. bYield of the inseparable mixture of pyrazoles. crt, 168 h, dichloromethane/water. Conversion of the reaction is in brackets: ( ). d40 °C, 72 h, dichloromethane/water. eA mixture of 20b/20a (4/1) is formed, from which pure isomer 20b is isolated by crystallization in 62% yield.

Structures of compounds 10a, 19b, 20b were confirmed by X-ray crystal structure analysis (Figure 3) [50].

![[1860-5397-11-3-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-11-3-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: X-ray crystal structure of pyrazoles 10a, 19b and 20b [50].

Figure 3: X-ray crystal structure of pyrazoles 10a, 19b and 20b [50].

Reaction regioselectivity

Monosubstituted alkynes 1–12 regioselectively reacted with C2F5CHN2 to give only 3,5-disubstituted pyrazoles. Formation of 3,4-disubstituted isomers was observed.

Disubstituted alkynes behaved differently, because of controversial electronic and steric effects. According to the orbital symmetry rules, the [3 + 2] cycloaddition must lead to pyrazoles with the C2F5 group and EWG at 3,5-positions [49]. Product 18a/b was obtained as a mixture of isomers because the C2F5 and CO2Et had similar electron-withdrawing nature. On the contrary, reaction of alkyne 19 having both the electron-withdrawing (–COMe) and electron-donating (–SiMe3) substituents afforded the isomer 19b with EWG at the 4th position, violating the orbital symmetry rules (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Presumably, the steric repulsion between bulky C2F5 and SiMe3 groups forced the reaction to follow the reversed regioselectivity – the steric effect has overcompensated the electronic one (Figure 4) [51,52].

Figure 4: Structure of the expected product 19a, and the observed isomeric one – 19b.

Figure 4: Structure of the expected product 19a, and the observed isomeric one – 19b.

Replacing one hydrogen atom in alkyne 19 by a bulkier chlorine atom – alkyne 20 – led to mixture of products 20b/a = 4.0/1.0 (the pure product 20b was obtained by crystallization). Replacing two hydrogen atoms in 20 by bulkier fluorine atoms – alkyne 21 – led to mixture 21b/a = 2.6/1.0. In compounds 13–15 the steric effect overcompensated the electronic one, but the impact of steric effect decreased with increasing the size of the second substituent: CH3CO (19), ClCH2CO (20), HF2CCO (21) increasing the percentage of α-isomers (0% in 19b, 20% in 20a/b, 28% in 21a/b).

Reactivity of C2F5CHN2 vs CF3CHN2

To compare the reactivities of C2F5CHN2 and CF3CHN2 in [3 + 2] cycloadditions with alkynes, one must take into account two factors: steric and electronic [49]. On one hand, the C2F5 substituent is bulkier than the CF3 one, decreasing thereby the reactivity of C2F5CHN2 compared with CF3CHN2. On the other hand, C2F5 and CF3 groups have similar electron-withdrawing abilities [1], and hence the both diazoalkanes might have similar reactivities. In reality, under the same conditions, after seven days at room temperature alkyne 19 reacted with CF3CHN2 completely, while the corresponding reaction with C2F5CHN2 reached only 52% conversion. Obviously, the steric effect overcompensated the electronic one; and C2F5CHN2 was less active than CF3CHN2 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Comparison of CF3CHN2 vs C2F5CHN2 in the reaction with alkyne 19.

Scheme 1: Comparison of CF3CHN2 vs C2F5CHN2 in the reaction with alkyne 19.

Another factor, however, must be kept in mind while comparing the reactivities of C2F5CHN2 and CF3CHN2: the reactions of C2F5CHN2 can be safely heated up to 40–45 °C without evaporation of the reagent while those with CF3CHN2 cannot (bp = 13 °C) [53]. Therefore, the yield of product 19b was improved to 73% by performing the reaction at 40 °C.

Selected chemical transformations

Having developed a robust practical method to C2F5-pyrazoles, the true practical potential of the obtained compounds was demonstrated. First, the standard cleavage of TMS group in 19b led to ketone 24 (Scheme 2). This strategy gives an opportunity for preparing the 3,4-disubstituted pyrazoles from TMS-derivatives, while the direct reaction of monosubstituted alkynes 1–12 with C2F5CHN2 gives 3,5-disubstituted ones.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted pyrazole 24.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted pyrazole 24.

Also, alkaline hydrolysis of the ester group in 1a gave acid 25 – potential building blocks for medicinal chemistry and drug discovery: many bioactive compounds, including the insecticidal agent DP-23, contain the residue of the CF3-analogue of 25 (Scheme 3) [54].

Finally, alkylation of pyrazole 1a with MeI afforded the product 26 in 69% yield after column chromatography. Basic hydrolysis of the ester group in 26 gave acid 27 – another potential building block for drug discovery (the corresponding CF3-acid constitutes to the known antiviral agent AS-136A [55]) (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3: Synthesis of C2F5-substituted acids 25 and 27. In brackets are the known bioactive compounds DP-23, AS-136A (CF3-analogues of 25 and 27).

Scheme 3: Synthesis of C2F5-substituted acids 25 and 27. In brackets are the known bioactive compounds DP-23, ...

Conclusion

In summary, a novel approach to C2F5-substituted pyrazoles has been elaborated by a three-component reaction between C2F5CH2NH2·HCl, NaNO2 and electron-deficient alkynes. This method is highly practical: it does not require a) the pre-isolation of toxic diazo intermediates; b) inert gas atmosphere (the reaction is performed in air); c) any catalysts; d) purification of the products by column chromatography. Also, the reaction works for both the mono- and disubstituted alkynes; and allows preparing of 3,5- and 3,4-disubstituted pyrazoles (via SiMe3-alkynes).

Therefore, given the importance of fluorinated pyrazoles, it is desirable that scientists will soon use this extremely useful practical reaction in synthetic organic chemistry, drug discovery and agrochemistry (where the need for robust reactions is high).

Experimental

General procedure: To a stirred suspension of C2F5CH2NH2·HCl (90 mg, 0.48 mmol, 3.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (4.0 mL)/water (0.2 mL), sodium nitrite (54 mg, 0.78 mmol, 5.0 equiv) and alkyne (0.16 mmol, 1.0 equiv) were added. The reaction mixture was vigorously stirred at 20 °C for 72 h. Water (1.0 mL) and CH2Cl2 (3 mL) were added. The organic layer was separated. The aqueous layer was washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 3 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated under vacuum to provide the pure product.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures and copies of NMR spectra for all new compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.8 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

All chemicals were generously provided by Enamine Ltd. I am very grateful to O. Ishenko and V. Stepanenko for the kind gift of C2F5CH2NH2·HCl; O. Gerashenko for alkyne 4, O. Denisenko and T. Drujenko for alkyne 8, A. Tymtsunik for alkyne 11, B. Chalyk for alkynes 18 and 21. I also thank Prof. Oleg Shishkin for X-ray crystallographic analysis; and A. Scherbatyuk, R. Iminov, V. Yarmolchuk and O. Mashkov for the help in managing this project.

References

-

Hiyama, T.; Yamamoto, T., Eds. Organofluorine Compounds – Chemistry and Application; Springer, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04164-2

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Ojima, I., Ed. Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology; Blackwell Publishing, 2009.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gouverneur, V.; Müller, K., Eds. Fluorine in Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry: From Biophysical Aspects to Clinical Applications; Imperial College Press: London, 2012. doi:10.1142/p746

Return to citation in text: [1] -

O'Hagan, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2010, 131, 1071. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2010.03.003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Müller, K.; Faeh, C.; Diederich, F. Science 2007, 317, 1881. doi:10.1126/science.1131943

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Purser, S.; Moore, P. R.; Swallow, S.; Gouverneur, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320. doi:10.1039/b610213c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hagmann, W. K. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4359. doi:10.1021/jm800219f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Böhm, H.-J.; Banner, D.; Bendels, S.; Kansy, M.; Kuhn, B.; Müller, K.; Obst-Sander, U.; Stahl, M. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 637. doi:10.1002/cbic.200301023

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Isanbor, C.; O'Hagan, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 303. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.01.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bégué, J.-P.; Bonnet-Delpon, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 992. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.05.006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kirk, K. L. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 1013. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.06.007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, A.; Yoon, J.-J.; Yin, Y.; Prussia, A.; Yang, Y.; Min, J.; Plemper, R. K.; Snyder, J. P. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 3731. doi:10.1021/jm701239a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yonetoku, Y.; Kubota, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Toyoshima, A.; Funatsu, M.; Ishikawa, J.; Takeuchi, M.; Ohta, M.; Tsukamoto, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 14, 4750. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.03.024

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yonetoku, Y.; Kubota, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Ishikawa, J.; Takeuchi, M.; Ohta, M.; Tsukamoto, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 14, 5370. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.03.039

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yonetoku, Y.; Kubota, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; Okamoto, Y.; Funatsu, M.; Yoshimura-Ishikawa, N.; Ishikawa, J.; Yoshino, T.; Takeuchi, M.; Ohta, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 9457. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.047

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chowdhury, M. A.; Abdellatif, K. R. A.; Dong, Y.; Das, D.; Suresh, M. R.; Knaus, E. E. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 1525. doi:10.1021/jm8015188

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, K. H.; Veal, J. M.; Fadden, R. P.; Rice, J. W.; Eaves, J.; Strachan, J.-P.; Barabasz, A. F.; Foley, B. E.; Barta, T. E.; Ma, W.; Silinski, M. A.; Hu, M.; Partridge, J. M.; Scott, A.; DuBois, L. G.; Freed, T.; Steed, P. M.; Ommen, A. J.; Smith, E. D.; Hughes, P. F.; Woodward, A. R.; Hanson, G. J.; McCall, W. S.; Markworth, C. J.; Hinkley, L.; Jenks, M.; Geng, L.; Lewis, M.; Otto, J.; Pronk, B.; Verleysen, K.; Hall, S. E. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4288. doi:10.1021/jm900230j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maggio, B.; Raffa, D.; Raimondi, M. V.; Cascioferro, S.; Plescia, F.; Tolomeo, M.; Barbusca, E.; Cannizzo, G.; Mancuso, S.; Daidone, G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 2386. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.01.007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ward, S. E.; Harries, M.; Aldegheri, L.; Austin, N. E.; Ballantine, S.; Ballini, E.; Bradley, D. M.; Bax, B. D.; Clarke, B. P.; Harris, A. J.; Harrison, S. A.; Melarange, R. A.; Mookherjee, C.; Mosley, J.; Dal Negro, G.; Oliosi, B.; Smith, K. J.; Thewlis, K. M.; Woollard, P. M.; Yusaf, S. P. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 78. doi:10.1021/jm100679e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qi, J.; Zhang, F.; Mi, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Y.; Du, X.; Jia, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 934. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.01.010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Djuric, S. W.; BaMaung, N. Y.; Basha, A.; Liu, H.; Luly, J. R.; Madar, D. J.; Sciotti, R. J.; Tu, N. P.; Wagenaar, F. L.; Wiedeman, P. E.; Zhou, X.; Ballaron, S.; Bauch, J.; Chen, Y.-W.; Chiou, X. G.; Fey, T.; Gauvin, D.; Gubbins, E.; Hsieh, G. C.; Marsh, K. C.; Mollison, K. W.; Pong, M.; Shaughnessy, T. K.; Sheets, M. P.; Smith, M.; Trevillyan, J. M.; Warrior, U.; Wegner, C. D.; Carter, G. W. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 2975. doi:10.1021/jm990615a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Giornal, F.; Pazenok, S.; Rodefeld, L.; Lui, N.; Vors, J.-P.; Leroux, F. R. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013, 152, 2. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2012.11.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fustero, S.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Barrio, P.; Simón-Fuentes, A. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6984. doi:10.1021/cr2000459

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Halcrow, M. A. Dalton Trans. 2009, 2059. doi:10.1039/b815577a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mukherjee, R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 203, 151. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00144-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jayaratna, N. B.; Gerus, I. I.; Mironets, R. V.; Mykhailiuk, P. K.; Yousufuddin, M.; Dias, H. V. R. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 1691. doi:10.1021/ic302715d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gerus, I. I.; Mironetz, R. X.; Kondratov, I. S.; Bezdudny, A. V.; Dmytriv, Y. V.; Shishkin, O. V.; Starova, V. S.; Zaporozhets, O. A.; Tolmachev, A. A.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 47. doi:10.1021/jo202305c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wishart, D. S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A. C.; Cheng, D.; Shrivastaya, S.; Tzur, D.; Gautam, B.; Hassanali, M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36 (Suppl. 1), D901. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm958

At least 45 FDA-approved drugs contain the trifluoromethyl group.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 6119. doi:10.1021/cr030143e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Macé, Y.; Magnier, E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2479. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201101535

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Altomonte, S.; Zanda, M. J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 143, 57. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2012.06.030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Andrzejewska, M.; Yépez-Mulia, L.; Cedillo-Rivera, R.; Tapia, A.; Vilpo, L.; Vilpo, J.; Kazimierczuk, Z. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 37, 973. doi:10.1016/S0223-5234(02)01421-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Johansson, A.; Poliakov, A.; Åkerblom, E.; Wiklund, K.; Lindeberg, G.; Winiwarter, S.; Danielson, U. H.; Samuelsson, B.; Hallberg, A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 2551. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(03)00179-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jonat, W.; Bachelot, T.; Ruhstaller, T.; Kuss, I.; Reimann, U.; Robertson, J. F. R. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2543. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt216

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Croxtall, J. D.; McKeage, K. Drugs 2011, 71, 363. doi:10.2165/11204810-000000000-00000

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Taka, N.; Koga, H.; Sato, H.; Ishizawa, T.; Takahashi, T.; Imagawa, J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 1393. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(00)00064-X

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

During the past five years, C2F5-substituted pyrazoles were used in ca. 30 medicinal and agrochemical patents according to “Reaxys” database (the search was performed in February 2014).

Return to citation in text: [1] -

According to the “Reaxys” database, synthesis of 3-CF3-pyrazoles is covered in 676 articles, while synthesis of 3-C2F5-pyrazoles is mentioned in only 27 articles.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pazenok, S.; Giornal, F.; Landelle, G.; Lui, N.; Vors, J.-P.; Leroux, F. R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 4249. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300561

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Desens, W.; Winterberg, M.; Büttner, S.; Michalik, D.; Saghyan, A. S.; Villinger, A.; Fischer, C.; Langer, P. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3459. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2013.02.059

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khlebnikova, T. S.; Piven, Yu. A.; Baranovskii, A. V.; Lakhvich, F. A. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 49, 421. doi:10.1134/S1070428013030184

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fustero, S.; Román, R.; Sanz-Cervera, J. F.; Simón-Fuentes, A.; Cuñat, A. C.; Villanova, S.; Murguía, M. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 3523. doi:10.1021/jo800251g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Man, S.; Nečas, M.; Bouillon, J.-P.; Portella, C.; Potáček, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 3473. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200600175

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Martins, M. A. P.; Pereira, C. M. P.; Zimmermann, N. E. K.; Cunico, W.; Moura, S.; Beck, P.; Zanatta, N.; Bonacorso, H. G. J. Fluorine Chem. 2003, 123, 261. doi:10.1016/S0022-1139(03)00163-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, F.; Nie, J.; Sun, L.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.-A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6255. doi:10.1002/anie.201301870

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Slobodyanyuk, E. Y.; Artamonov, O. S.; Shishkin, O. V.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2487. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301852

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mykhailiuk, P. K. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 4942. doi:10.1002/chem.201304840

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Husted, D. R.; Ahlbrecht, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 1605. doi:10.1021/ja01103a026

C2F5CH2NH2·HCl can be prepared from pentafluoropropyonic acid according to this literature.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zollinger, H. Diazo Chemistry I and II; VCH: Weinheim, 1994.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

СCDC numbers: 990391 (10a), 974944 (19b), 990392 (20b).

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Huisgen, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1963, 2, 633. doi:10.1002/anie.196306331

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maas, G. Diazoalkanes. In Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry toward Heterocycles and Natural Products; Padwa, A.; Pearson, W. H., Eds.; Johm Wiley & Sons: New York, 2002; Vol. 59, pp 539–621. doi:10.1002/0471221902.ch8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gilman, H.; Jones, R. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1943, 65, 1458. doi:10.1021/ja01248a005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lahm, G. P.; Selby, T. P.; Freudenberger, J. H.; Stevenson, T. M.; Myers, B. J.; Seburyamo, G.; Smith, B. K.; Flexner, L.; Clark, C. E.; Cordova, D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4898. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.034

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, A.; Chandrakumar, N.; Yoon, J.-J.; Plemper, R. K.; Snyder, J. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5199. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.084

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Hiyama, T.; Yamamoto, T., Eds. Organofluorine Compounds – Chemistry and Application; Springer, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04164-2 |

| 2. | Ojima, I., Ed. Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology; Blackwell Publishing, 2009. |

| 3. | Gouverneur, V.; Müller, K., Eds. Fluorine in Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry: From Biophysical Aspects to Clinical Applications; Imperial College Press: London, 2012. doi:10.1142/p746 |

| 4. | O'Hagan, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2010, 131, 1071. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2010.03.003 |

| 5. | Müller, K.; Faeh, C.; Diederich, F. Science 2007, 317, 1881. doi:10.1126/science.1131943 |

| 6. | Purser, S.; Moore, P. R.; Swallow, S.; Gouverneur, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320. doi:10.1039/b610213c |

| 7. | Hagmann, W. K. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4359. doi:10.1021/jm800219f |

| 8. | Böhm, H.-J.; Banner, D.; Bendels, S.; Kansy, M.; Kuhn, B.; Müller, K.; Obst-Sander, U.; Stahl, M. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 637. doi:10.1002/cbic.200301023 |

| 16. | Chowdhury, M. A.; Abdellatif, K. R. A.; Dong, Y.; Das, D.; Suresh, M. R.; Knaus, E. E. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 1525. doi:10.1021/jm8015188 |

| 1. | Hiyama, T.; Yamamoto, T., Eds. Organofluorine Compounds – Chemistry and Application; Springer, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04164-2 |

| 31. | Altomonte, S.; Zanda, M. J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 143, 57. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2012.06.030 |

| 13. | Yonetoku, Y.; Kubota, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Toyoshima, A.; Funatsu, M.; Ishikawa, J.; Takeuchi, M.; Ohta, M.; Tsukamoto, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 14, 4750. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.03.024 |

| 14. | Yonetoku, Y.; Kubota, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Ishikawa, J.; Takeuchi, M.; Ohta, M.; Tsukamoto, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 14, 5370. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.03.039 |

| 15. | Yonetoku, Y.; Kubota, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; Okamoto, Y.; Funatsu, M.; Yoshimura-Ishikawa, N.; Ishikawa, J.; Yoshino, T.; Takeuchi, M.; Ohta, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 9457. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.047 |

| 32. | Andrzejewska, M.; Yépez-Mulia, L.; Cedillo-Rivera, R.; Tapia, A.; Vilpo, L.; Vilpo, J.; Kazimierczuk, Z. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 37, 973. doi:10.1016/S0223-5234(02)01421-6 |

| 33. | Johansson, A.; Poliakov, A.; Åkerblom, E.; Wiklund, K.; Lindeberg, G.; Winiwarter, S.; Danielson, U. H.; Samuelsson, B.; Hallberg, A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 2551. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(03)00179-2 |

| 12. | Sun, A.; Yoon, J.-J.; Yin, Y.; Prussia, A.; Yang, Y.; Min, J.; Plemper, R. K.; Snyder, J. P. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 3731. doi:10.1021/jm701239a |

| 28. |

Wishart, D. S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A. C.; Cheng, D.; Shrivastaya, S.; Tzur, D.; Gautam, B.; Hassanali, M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36 (Suppl. 1), D901. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm958

At least 45 FDA-approved drugs contain the trifluoromethyl group. |

| 54. | Lahm, G. P.; Selby, T. P.; Freudenberger, J. H.; Stevenson, T. M.; Myers, B. J.; Seburyamo, G.; Smith, B. K.; Flexner, L.; Clark, C. E.; Cordova, D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4898. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.034 |

| 9. | Isanbor, C.; O'Hagan, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 303. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.01.011 |

| 10. | Bégué, J.-P.; Bonnet-Delpon, D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 992. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.05.006 |

| 11. | Kirk, K. L. J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 1013. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.06.007 |

| 1. | Hiyama, T.; Yamamoto, T., Eds. Organofluorine Compounds – Chemistry and Application; Springer, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04164-2 |

| 29. | Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 6119. doi:10.1021/cr030143e |

| 30. | Macé, Y.; Magnier, E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2479. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201101535 |

| 55. | Sun, A.; Chandrakumar, N.; Yoon, J.-J.; Plemper, R. K.; Snyder, J. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5199. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.084 |

| 20. | Qi, J.; Zhang, F.; Mi, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Y.; Du, X.; Jia, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 934. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.01.010 |

| 22. | Giornal, F.; Pazenok, S.; Rodefeld, L.; Lui, N.; Vors, J.-P.; Leroux, F. R. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013, 152, 2. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2012.11.008 |

| 23. | Fustero, S.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Barrio, P.; Simón-Fuentes, A. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6984. doi:10.1021/cr2000459 |

| 1. | Hiyama, T.; Yamamoto, T., Eds. Organofluorine Compounds – Chemistry and Application; Springer, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04164-2 |

| 19. | Ward, S. E.; Harries, M.; Aldegheri, L.; Austin, N. E.; Ballantine, S.; Ballini, E.; Bradley, D. M.; Bax, B. D.; Clarke, B. P.; Harris, A. J.; Harrison, S. A.; Melarange, R. A.; Mookherjee, C.; Mosley, J.; Dal Negro, G.; Oliosi, B.; Smith, K. J.; Thewlis, K. M.; Woollard, P. M.; Yusaf, S. P. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 78. doi:10.1021/jm100679e |

| 24. | Halcrow, M. A. Dalton Trans. 2009, 2059. doi:10.1039/b815577a |

| 25. | Mukherjee, R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 203, 151. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00144-7 |

| 26. | Jayaratna, N. B.; Gerus, I. I.; Mironets, R. V.; Mykhailiuk, P. K.; Yousufuddin, M.; Dias, H. V. R. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 1691. doi:10.1021/ic302715d |

| 27. | Gerus, I. I.; Mironetz, R. X.; Kondratov, I. S.; Bezdudny, A. V.; Dmytriv, Y. V.; Shishkin, O. V.; Starova, V. S.; Zaporozhets, O. A.; Tolmachev, A. A.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 47. doi:10.1021/jo202305c |

| 53. | Gilman, H.; Jones, R. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1943, 65, 1458. doi:10.1021/ja01248a005 |

| 18. | Maggio, B.; Raffa, D.; Raimondi, M. V.; Cascioferro, S.; Plescia, F.; Tolomeo, M.; Barbusca, E.; Cannizzo, G.; Mancuso, S.; Daidone, G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 2386. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.01.007 |

| 51. | Huisgen, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1963, 2, 633. doi:10.1002/anie.196306331 |

| 52. | Maas, G. Diazoalkanes. In Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry toward Heterocycles and Natural Products; Padwa, A.; Pearson, W. H., Eds.; Johm Wiley & Sons: New York, 2002; Vol. 59, pp 539–621. doi:10.1002/0471221902.ch8 |

| 17. | Huang, K. H.; Veal, J. M.; Fadden, R. P.; Rice, J. W.; Eaves, J.; Strachan, J.-P.; Barabasz, A. F.; Foley, B. E.; Barta, T. E.; Ma, W.; Silinski, M. A.; Hu, M.; Partridge, J. M.; Scott, A.; DuBois, L. G.; Freed, T.; Steed, P. M.; Ommen, A. J.; Smith, E. D.; Hughes, P. F.; Woodward, A. R.; Hanson, G. J.; McCall, W. S.; Markworth, C. J.; Hinkley, L.; Jenks, M.; Geng, L.; Lewis, M.; Otto, J.; Pronk, B.; Verleysen, K.; Hall, S. E. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4288. doi:10.1021/jm900230j |

| 21. | Djuric, S. W.; BaMaung, N. Y.; Basha, A.; Liu, H.; Luly, J. R.; Madar, D. J.; Sciotti, R. J.; Tu, N. P.; Wagenaar, F. L.; Wiedeman, P. E.; Zhou, X.; Ballaron, S.; Bauch, J.; Chen, Y.-W.; Chiou, X. G.; Fey, T.; Gauvin, D.; Gubbins, E.; Hsieh, G. C.; Marsh, K. C.; Mollison, K. W.; Pong, M.; Shaughnessy, T. K.; Sheets, M. P.; Smith, M.; Trevillyan, J. M.; Warrior, U.; Wegner, C. D.; Carter, G. W. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 2975. doi:10.1021/jm990615a |

| 37. | During the past five years, C2F5-substituted pyrazoles were used in ca. 30 medicinal and agrochemical patents according to “Reaxys” database (the search was performed in February 2014). |

| 34. | Jonat, W.; Bachelot, T.; Ruhstaller, T.; Kuss, I.; Reimann, U.; Robertson, J. F. R. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2543. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt216 |

| 35. | Croxtall, J. D.; McKeage, K. Drugs 2011, 71, 363. doi:10.2165/11204810-000000000-00000 |

| 36. | Taka, N.; Koga, H.; Sato, H.; Ishizawa, T.; Takahashi, T.; Imagawa, J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 1393. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(00)00064-X |

| 34. | Jonat, W.; Bachelot, T.; Ruhstaller, T.; Kuss, I.; Reimann, U.; Robertson, J. F. R. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2543. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt216 |

| 35. | Croxtall, J. D.; McKeage, K. Drugs 2011, 71, 363. doi:10.2165/11204810-000000000-00000 |

| 36. | Taka, N.; Koga, H.; Sato, H.; Ishizawa, T.; Takahashi, T.; Imagawa, J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 1393. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(00)00064-X |

| 48. |

Husted, D. R.; Ahlbrecht, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 1605. doi:10.1021/ja01103a026

C2F5CH2NH2·HCl can be prepared from pentafluoropropyonic acid according to this literature. |

| 1. | Hiyama, T.; Yamamoto, T., Eds. Organofluorine Compounds – Chemistry and Application; Springer, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04164-2 |

| 45. | Li, F.; Nie, J.; Sun, L.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.-A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6255. doi:10.1002/anie.201301870 |

| 46. | Slobodyanyuk, E. Y.; Artamonov, O. S.; Shishkin, O. V.; Mykhailiuk, P. K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2487. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301852 |

| 38. | According to the “Reaxys” database, synthesis of 3-CF3-pyrazoles is covered in 676 articles, while synthesis of 3-C2F5-pyrazoles is mentioned in only 27 articles. |

| 39. | Pazenok, S.; Giornal, F.; Landelle, G.; Lui, N.; Vors, J.-P.; Leroux, F. R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 4249. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201300561 |

| 40. | Desens, W.; Winterberg, M.; Büttner, S.; Michalik, D.; Saghyan, A. S.; Villinger, A.; Fischer, C.; Langer, P. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3459. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2013.02.059 |

| 41. | Khlebnikova, T. S.; Piven, Yu. A.; Baranovskii, A. V.; Lakhvich, F. A. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 49, 421. doi:10.1134/S1070428013030184 |

| 42. | Fustero, S.; Román, R.; Sanz-Cervera, J. F.; Simón-Fuentes, A.; Cuñat, A. C.; Villanova, S.; Murguía, M. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 3523. doi:10.1021/jo800251g |

| 43. | Man, S.; Nečas, M.; Bouillon, J.-P.; Portella, C.; Potáček, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 3473. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200600175 |

| 44. | Martins, M. A. P.; Pereira, C. M. P.; Zimmermann, N. E. K.; Cunico, W.; Moura, S.; Beck, P.; Zanatta, N.; Bonacorso, H. G. J. Fluorine Chem. 2003, 123, 261. doi:10.1016/S0022-1139(03)00163-5 |

© 2015 Mykhailiuk; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)