Abstract

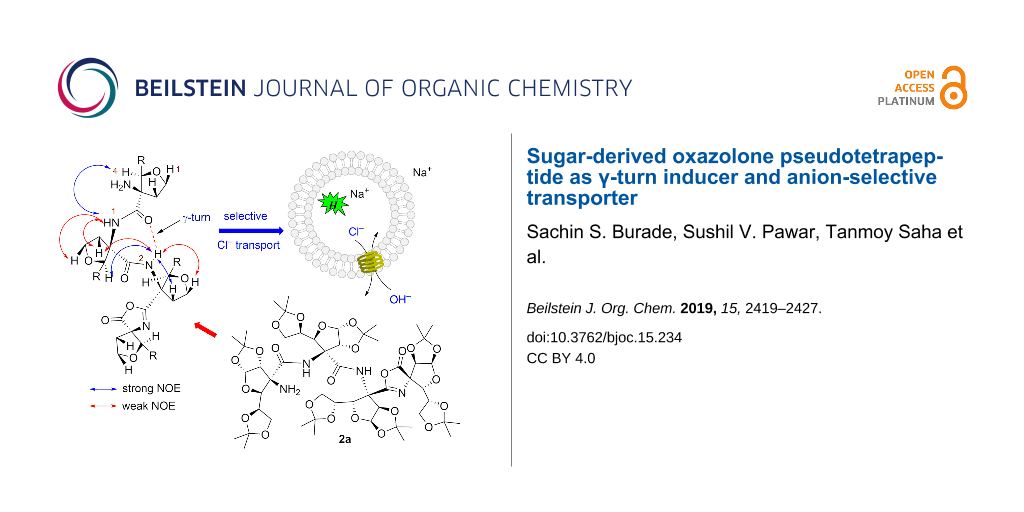

The intramolecular cyclization of a C-3-tetrasubstituted furanoid sugar amino acid-derived linear tetrapeptide afforded an oxazolone pseudo-peptide with the formation of an oxazole ring at the C-terminus. A conformational study of the oxazolone pseudo-peptide showed intramolecular C=O···HN(II) hydrogen bonding in a seven-membered ring leading to a γ-turn conformation. This fact was supported by a solution-state NMR and molecular modeling studies. The oxazolone pseudotetrapeptide was found to be a better Cl−-selective transporter for which an anion–anion antiport mechanism was established.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Tetrasubstituted α-amino acid (TAA)-derived peptidomimetics offer well-defined turn structures due to the presence of a stereochemically stable quaternary carbon center [1]. For example, TAA-derived peptides containing a cyclopropane ring and ʟ/ᴅ-dimethyl tartrate showed an α-turn and form 310-helical conformations in higher oligomers [2-4]. While, TAA-derived peptides having a tetrahydrofuran ring demonstrated a β-turn type conformation [5]. Amongst these, the use of sugar-derived TAAs in peptidomimetics is less explored. The linear tri-/tetrapeptides and spiro-peptides at the anomeric position of mannofructose are known [6-8]. Stick and co-workers have reported the synthesis of tetrasubstituted sugar furanoid amino acid (TSFAA)-derived homologated linear pentapeptide which showed a well defined intramolecular hydrogen-bonding-stabilized helical array [9-11]. Our group has reported a trans-vicinal ᴅ-glucofuranoroic-3,4-diacid with a TAA framework and incorporated it into the N-terminal tetrapeptide sequence (H-Phe-Trp-Lys-Thy-OH) to get a glycopeptide which acts as an α-turn inducer [12]. Over the last several years, synthetic peptides are known to play a significant role in the design of artificial ion transport systems [13-16]. Recently, our group has synthesized fluorinated acyclic and cyclic peptides from C-3 fluorinated ᴅ-glucofuranoid amino acids and demonstrated their selective anion transport activity [17,18]. In continuation of our interest in sugar-derived cyclic peptides [19], we aimed to synthesize cyclic peptides I and II from the corresponding linear di- and tetrapeptides, however, we obtained an oxazolone ring containing pseudo peptides 1 and 2a, respectively (Figure 1) The NMR studies of pseudotetrapeptide 2a indicated a γ-turn conformation stabilized by the intramolecular hydrogen bonding [(II)NH···O=C] in a seven-membered ring. The oxazolone pseudotetrapeptide 2a demonstrated better selective Cl− ion transport activity as compared to the pseudodipeptide 1. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the formation of oxazolone peptides from TSFAA that induces a γ-turn and demonstrate ion transport activity.

Figure 1: Oxazolone pseudodipeptide 1 and tetrapeptide 2a.

Figure 1: Oxazolone pseudodipeptide 1 and tetrapeptide 2a.

Results and Discussion

At first, ᴅ-glucose was converted to C-3-tetrasubstituted furanoid sugar azido ester 3 as per our reported protocol [12]. Hydrolysis of the ester functionality in 3 with LiOH at room temperature afforded azido acid 4a in 92% yield, while hydrogenation of 3 using 10% Pd/C in MeOH at room temperature for 3 h afforded the amino ester 4b in 86% yield (Scheme 1). The coupling of 4a and 4b using 2-chloro-1-N-methylpyridinium iodide (CMPI), as a coupling reagent, in the presence of Et3N in dichloromethane at 40 °C for 12 h gave azido ester dipeptide 5 in 75% yield. Hydrogenation of 5 using 10% Pd/C in methanol gave amino ester dipeptide 6a in 82% yield, while hydrolysis of 5 using LiOH gave azido acid dipeptide 6b in 88% yield. Coupling of 6a and 6b using CMPI in the presence of Et3N in dichloromethane afforded azido ester tetra-peptide 7 in 73% yield. [20].

Scheme 1: Synthesis of linear azido ester dipeptide 5 and tetrapeptide 7.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of linear azido ester dipeptide 5 and tetrapeptide 7.

The linear azido ester dipeptide 5 and tetrapeptide 7 were individually converted to amino acid di- and tetrapeptides 8 and 9, respectively, using hydrolysis followed by a hydrogenation reaction protocol (Scheme 2). In order to get cyclic peptides I and II (Figure 1), an individual intramolecular coupling reaction of linear dipeptide 8 and tetrapeptide 9 was attempted. Thus, coupling reactions of 8/9 with different reagents (HATU, TBTU, PyBOP, EDC·HCl), under a variety of solvents (DMF, acetonitrile, dichloromethane) and reaction conditions (25–80 °C for 24 h) were unsuccessful. This could be due to the stable helical conformation of 8 and 9 in which reactive acid and amino functionalities are apart from each other. However, an individual intramolecular coupling reaction of 8 and 9 using CMPI as a coupling reagent, in the presence of Et3N in dichloromethane, afforded pseudodipeptide 1 and pseudotetrapeptide 2a, respectively, with oxazolone ring formation at the C-terminal of the peptides [21-23]. The free amino group in 2a was acetylated with Ac2O/pyridine in dichloromethane to get –NHAc derivative 2b (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of oxazolone pseudopeptides 1, 2a and 2b.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of oxazolone pseudopeptides 1, 2a and 2b.

The single crystal formation of oxazolone psudopeptides 1, 2a and 2b were unsuccessful under a variety of solvent conditions. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 1, 2a and 2b showed sharp and well-resolved signals in CDCl3 solution indicating the absence of rotational isomers (Figures S1, S3, and S4 in Supporting Information File 1). The oxazolone pseudodipeptide 1 is devoid of amide linkages and is therefore not considered for conformational studies [24]. In the case of 2a, the assignment of chemical shifts to different protons was made based on 1H,1H-COSY, 1H,13C-HMBC/HSQC, NOESY, and 1H,15N-HSQC/HMBC studies (Figures S5–S10 in Supporting Information File 1) and values thus obtained are given in Table S1 in Supporting Information File 1. The IR spectrum of 2a showed a broad band at 3444–3421 cm−1 indicating the presence of -NHs of amine/amide functionalities. The bands at 1740 and 1688 cm−1 were assigned to the lactone carbonyl and amide (as well as imine) groups, respectively. In the 1H NMR spectrum, the downfield signals at δ 9.03 and 8.52 ppm were assigned to the amide NH(I) and NH(II), respectively. The signal at δ 1.80 ppm, integrating for two protons, was assigned to the presence of an NH2 functionality. In the 13C NMR spectrum, the appearance of signals at δ 170.8, 170.6 and 166.7 ppm were assigned to the lactone/amide carbonyl functionalities. The signal at δ 163.0 ppm was assigned to the -C=N functionality. The 1H,15N-HSQC and 1H,15N-HMBC spectra showed a signal at δ 246.0 ppm that was assigned to the imine (C=N-) nitrogen. The signal at δ 26.2 ppm was assigned to the amine (NH2) nitrogen. The signals at δ 112.8 and δ 114.1 ppm were due to the nitrogen of amide (CONH) groups. Based on the 15N NMR spectra, the presence of the oxazolone ring at the C-terminus in 2a was confirmed [21-23].

The 1H NMR spectra of N-acylated compound 2b showed three downfield signals at δ 8.24, 8.19 and 8.09 ppm due to the three amide NHs. An additional singlet at δ 2.0 ppm, integrating for three protons, was assigned to the NHCOCH3. In the 13C NMR spectrum, the appearance of five signals in the downfield region (at δ 171.6, 170.9, 167.5, 165.0, and 164.0 ppm) indicated the presence of three amides, lactone carbonyl and imine carbon (-C=N) suggesting the presence of oxazolone ring in 2b.

Conformational study of 2a

The downfield shift of amide NH protons δ > 7.5 ppm in 2a suggested the possible involvement of intramolecular hydrogen bonding [25]. The observed NOESY cross peaks of NH(I)↔NH2 indicated closer proximity and orientation on the same side (Figure 2). This is likely to involve (I)NH···NH2 weak intramolecular hydrogen bonding. The amide NH(II) showed strong cross peaks with H-2, H-5 of ring C, H-4 of ring B and weak cross peaks with H-1, H-6 of ring C indicating closer proximity and orientation of these protons on the same side. Appearance of strong NOE between NH(II)↔H-4 and weak NOE between NH(II)↔H-2 of ring B indicated the orientation of NH(II) towards the carbonyl group of ring A with the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonding in a seven-membered ring leading to the γ-turn conformation (Figure 2).

The involvement of amide NHs in intramolecular H-bonding was supported by the DMSO-d6 titration studies. Thus, 5 μL of DMSO-d6 was sequentially added (up to 50 μL) to the CDCl3 solution of 2a and change in δ value of NH protons was monitored by the 1H NMR [26]. The NH(I) proton showed the higher change in chemical shift ∆δ = 0.2 ppm indicating weak (I)NH···NH2 intramolecular H-bonding. The NH(II) showed smaller ∆δ = 0.13 ppm suggesting strong (II)NH···O=C intramolecular bonding (Figure 3).

This fact was further supported by a temperature-dependent 1H NMR study [27,28]. The temperature-dependent 1H NMR of 2a in CDCl3 as solvent at 283–323 K was recorded that showed a higher Δδ/ΔT value of 6.2 × 10−3 ppm/K for NH(I) indicating its involvement in weak intramolecular H-bonding. For NH(II) the lower Δδ/ΔT value of 3.7 × 10−3 ppm/K supported its association in strong intramolecular hydrogen bonding with C=O leading to the γ-turn formation (Figure 4).

![[1860-5397-15-234-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-234-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: 1H NMR temperature study of 2a.

Figure 4: 1H NMR temperature study of 2a.

The 1H NMR dilution study of 2a in CDCl3 solution showed the negligible change (∆δ = 0.01) in the chemical shift of NH(I) and(II) protons (Figure S17, Supporting Information File 1), further supporting their intramolecular hydrogen bonding with the free NH2 and C=O, respectively. These studies thus supported the presence of γ-turn helical type conformation of 2a.

Molecular modeling studies

In order to corroborate our results, obtained from the NMR studies, the molecular modeling study was performed using Spartan’14 software [29,30]. The initial geometry of 2a, generated from the NOESY study, was subjected to geometry optimization using a semi-empirical PM6 method. The resulted optimized structure of 2a indicated considerable crowding due to the presence of the oxazolone ring and two acetonide rings of sugar ring D (Figure 5A). To accumulate the oxazolone ring, the sugar ring C is pushed towards the A and B rings. The γ-turn conformation is stabilized by the intramolecular (II)NH···O=C hydrogen bonding in a seven-membered ring [bond distance (d) = 2.61 Å and bond angle (NH···O) = 114.06°]. To understand the role of the oxazolone ring in stabilizing the γ-turn, we performed geometry optimization on TFSAA linear tetrapeptide amino acid 9 (Figure 5C). The optimized geometry of 9 showed a change in helical conformation overcome the crowding due to acetonide groups. The N- and C-terminals are further away, thus precluding the γ-turn conformation [(bond distance (d) = 3.11 Å) and bond angle (NH···O) = 98.90°]. The comparison of geometrically optimized models of 2a and 9 showed small structural changes with respect to the helical pitch length. The distance between C=O···N(II) is 3.18 Å in 2a and 3.43 Å in 9. The distance between Cα1···Cα4 is 9.67 Å in 2a and 9.84 Å in 9 (Figure S18 in Supporting Information File 1). Similarly, the distance between N1···C4 is 9.44 Å in 2a and 10.47 Å in 9. This suggested an elongated helical structure of linear tetrapeptide 9 than 2a. Thus, the compact helical architecture of 2a is due to the presence of the oxazolone ring leading to a γ-turn conformation. The molecular modeling study of N-acetylated compound 2b also indicated the presence of a seven-membered hydrogen bonding between NH(II) and –C=O [bond distance (d) = 2.74 Å and bond angle (NH···O) = 112.98°] suggesting the presence of a γ-turn conformation (Figure 5B).

![[1860-5397-15-234-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-234-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: Optimized helical conformations of (A) 2a, (B) 2b and (C) 9.

Figure 5: Optimized helical conformations of (A) 2a, (B) 2b and (C) 9.

Ion transport activity

The cation and anion transport across lipid bilayer membranes plays a crucial role in various biological processes [31,32]. Amongst these, the transport of anions is useful in regulating intracellular pH, membrane potential, cell volume, and fluid transport [33]. Any dysfunction in these processes led to various diseases such as cystic fibrosis, Dent disease, Bartter syndrome, and epilepsy [34-37]. In order to mimic the regulatory functions in living systems, a wide range of anion transporters have been investigated that include peptides [38-43], oligoureas [44,45], anion-π slides [46,47], steroids [48,49], calixpyrroles [50,51], calixarenes [52,53], and other scaffolds [54-56]. In particular, peptide based transmembrane anion transporters have attracted great interest. For example, Ghadiri [38], Ranganathan [39], and Granja [40] have independently reported different types of cyclic peptides as anion transporters. Gale, Luis, and co-workers [41] have separately reported the linear pseudopeptides as receptors and transporters of chloride and nitrate anions.

Inspired by our recent ion transport studies with fluorinated acyclic and cyclic sugar derived peptides [17,18], we investigated the ion transport activity of 1 and 2a across lipid bilayer membranes. In this study, the collapse of the pH gradient (pHout = 7.8 and pHin = 7.0), created across egg yolk ʟ-α-phosphatidylcholine (EYPC) vesicles with entrapped 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid trisodium salt (HPTS) dye (i.e., EYPC-LUVsHPTS) [57-61] was monitored by measuring the fluorescence intensity of the dye at λem = 510 nm (λex = 450 nm) with time (Figure S11, Supporting Information File 1). Thus, the addition of 2a (10 µM) resulted in the significant increase in HPTS fluorescence within 200 s (Figure 6B), while oxazolone pseudodipeptide 1 was found to be lesser active (Figure 6A).

![[1860-5397-15-234-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-234-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Ion transport activity (A) for 1, (B) for 2a, across EYPC-LUVs HPTS.

Figure 6: Ion transport activity (A) for 1, (B) for 2a, across EYPC-LUVs HPTS.

From the dose–response data of 2a, the calculated effective concentration EC50 = 0.72 µM indicated good ion transport activity of 2a (Figure S12 in Supporting Information File 1). The Hill coefficient n value of 1.26 indicated that one molecule of 2a is involved in the formation of the active transporter. The promising ion transport activity of 2a encouraged us to explore its cation and anion selectivity study by varying either cations (for MCl, M+ = Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, and Cs+) or anions (for NaA, A− = F−, Cl−, Br−, I−, NO3−, SCN−, AcO− and ClO4−) of the extravesicular salt, respectively. Thus, variation of external cations, in the presence of 2a (0–10 µM), showed minor changes in the transport activity with the sequence: Na+ > Rb+ > Li+ > K+ ≈ Cs+ (Figure 7A), which suggest lesser influence of alkali metal cations in the transport process. However, variation of extravesicular anions demonstrated the changes in the transport behaviour with the following selectivity sequence: Cl– >> AcO– ≈ SCN– ≈ F– > NO3– >> Br– ≈ I–, showing highest selectivity for the Cl– ion (Figure 7B). Overall, anion variation had more influence in the ion transport rate compared to the cations.

![[1860-5397-15-234-7]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-234-7.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 7: Cation (A) and anion (B) transport activity of 2a.

Figure 7: Cation (A) and anion (B) transport activity of 2a.

Chloride leakage study

In order to know the role of the free NH2 group in 2a for Cl− recognition during the transport of the ion, we monitored the Cl− transport activities of the amino compound 2a and its N-acylated derivative 2b. The influx of Cl‒ ion by these transporters were monitored using EYPC-LUVslucigenin. Additionally, compound 9, which has a free amino group and a free carboxylic acid group, was also subjected to the Cl‒ transport study. The Cl– sensitive dye lucigenin, was entrapped within the lipid vesicles and the rate of quenching in fluorescence at λem = 535 nm (λex = 455 nm) was monitored using transporter 2a by creating a Cl– gradient across the lipid membrane by applying NaCl in the extravesicular buffer (Figure S14 in Supporting Information File 1). The compound 2a showed a significant decrease in the fluorescence rate of lucigenin and the change in fluorescence upon the addition of 2a (Figure 8A and 8B). We observed that the N-acetylated compound 2b was observed to be inactive (Figure 8A), indicating that the free amine group is necessary for the transport activity. Compound 9 did not exhibit any transport activity even at very high concentration (Figure S16 in Supporting Information File 1).

![[1860-5397-15-234-8]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-234-8.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 8:

Comparison of the ion transport activity of 2a and 2b at 20 µM across EYPC-LUVslucigenin (A). Concentration dependent activity of 2a across EYPC-LUVs

lucigenin (B). Transport activity of 2a (20 µM) by changing extravesicular cations (C). Transport activity of 2a (20 µM) in the presence and absence of valinomycin (1 µM) across EYPC-LUVs

lucigenin (D).

Figure 8:

Comparison of the ion transport activity of 2a and 2b at 20 µM across EYPC-LUVslucigenin (A). Conce...

Further, the variation of cations in the extravesicular buffer using different salts of MCl (M+ = Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, and Cs+) does not make any change in the transport rate of 2a (20 µM) which excludes any role of cation in an overall transport process (Figure 8C). Finally, to evaluate the mechanism of ion transport, the transport of Cl– using compound 2a (20 µM) was monitored in the presence and absence of valinomycin (a selective K+ transporter, 1 μM). There was a significant increase in the transport rate of 2a in the presence of valinomycin confirming the transport process occurring through an antiport mechanism via Cl−/NO3− exchange (Figure 8D). Such anion-selective transport can be rationalized based on the binding of anions with the terminal amino group of the transporter through hydrogen bond interaction. However, the role of the neighboring amido groups cannot be ruled out. Moreover, the hydrophobic outer surface of the transporter helps the anion bound complex to permeate efficiently through the lipid bilayer membranes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the intramolecular cyclization of linear di- and tetrapeptides 8 and 9 led to the formation of the oxazolone ring at the C-terminal giving pseudopeptides 1 and 2a, respectively. The pseudotetrapeptide 2a showed a γ-turn conformation that is stabilized by a seven-membered intramolecular hydrogen bonding. The pseudotetrapeptide 2a was found to facilitate selective anion transport that occurs by an anion–anion antiport mechanism. The absence of the γ-turn conformation as well as ion transport activity in linear tetrapeptide 9 – the precursor of 2a, suggest that the oxazolone ring in 2a is a γ-turn inducer as well as responsive for selective anion transport activity.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, 1H and 13C NMR data, HRMS and 2D NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.7 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), New Delhi (File no. EMR/2014/000873) for financial support and Central Instrumentation Facility (CIF), SPPU, Pune for analytical services. S.S.B. thanks CSIR, S.P, T.S., and M.A. thank the UGC, A.K, and N.K. thank the DSK-PDF New Delhi for providing a fellowships.

References

-

Maity, P.; Konig, B. Pept. Sci. 2008, 90, 8–27. doi:10.1002/bip.20902

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bonora, G. M.; Toniolo, C.; Di Blasio, B.; Pavone, V.; Pedone, C.; Benedetti, E.; Lingham, I.; Hardy, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 8152–8156. doi:10.1021/ja00338a025

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Toniolo, C.; Bonora, G. M.; Barone, V.; Bavoso, A.; Benedetti, E.; Di Blasio, B.; Grimaldi, P.; Lelj, F.; Pavone, V.; Pedone, C. Macromolecules 1985, 18, 895–902. doi:10.1021/ma00147a013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Demizu, Y.; Doi, M.; Kurihara, M.; Maruyama, T.; Suemune, H.; Tanaka, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 2430–2439. doi:10.1002/chem.201102902

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maity, P.; Zabel, M.; König, B. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 8046–8053. doi:10.1021/jo701423w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Estevez, J. C.; Estevez, R. J.; Ardron, H.; Wormald, M. R.; Brown, D.; Fleet, G. W. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 8885–8888. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78525-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Estevez, J. C.; Ardron, H.; Wormald, M. R.; Brown, D.; Fleet, G. W. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 8889–8890. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78526-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Estevez, J. C.; Smith, M. D.; Wormald, M. R.; Besra, G. S.; Brennan, P. J.; Nash, R. J.; Fleet, G. W. J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1996, 7, 391–394. doi:10.1016/0957-4166(96)00014-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Forman, G. S.; Scaffidi, A.; Stick, R. V. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 25–28. doi:10.1071/ch03214

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scaffidi, A.; Skelton, B. W.; Stick, R. V.; White, A. H. Aust. J. Chem. 2007, 60, 93–94. doi:10.1071/ch06392

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scaffidi, A.; Skelton, B. W.; Stick, R. V.; White, A. H. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 733–740. doi:10.1071/ch04014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vangala, M.; Dhokale, S. A.; Gawade, R. L.; Pattuparambil, R. R.; Puranik, V. G.; Dhavale, D. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6874–6878. doi:10.1039/c3ob41462k

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Djedovic, N.; Ferdani, R.; Harder, E.; Pajewska, J.; Pajewski, R.; Weber, M. E.; Schlesinger, P. H.; Gokel, G. W. New J. Chem. 2005, 29, 291–305. doi:10.1039/b417091c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

García-Fandiño, R.; Amorín, M.; Castedo, L.; Granja, J. R. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3280. doi:10.1039/c2sc21068a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sakai, N.; Houdebert, D.; Matile, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2003, 9, 223–232. doi:10.1002/chem.200390016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zeng, F.; Liu, F.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, S.; Shen, J.; Li, N.; Ren, H.; Zeng, H. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 4826–4830. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01723

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burade, S. S.; Shinde, S. V.; Bhuma, N.; Kumbhar, N.; Kotmale, A.; Rajamohanan, P. R.; Gonnade, R. G.; Talukdar, P.; Dhavale, D. D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 5826–5834. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00661

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Burade, S. S.; Saha, T.; Bhuma, N.; Kumbhar, N.; Kotmale, A.; Rajamohanan, P. R.; Gonnade, R. G.; Talukdar, P.; Dhavale, D. D. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5948–5951. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02942

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Pawar, N. J.; Diederichsen, U.; Dhavale, D. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 11278–11285. doi:10.1039/c5ob01673h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Synthesis of azido dipeptide 5 and tetrapeptide 7 is reported [11] using TsCl in pyridine as an activating agent for the carboxylic group. The same reaction at our hand gave the dark brown coloured product that on purification afforded ≈30% yield while; the use of CMPI as coupling reagent gave pale yellow solid product that on purification gave ≈75% yield of 5 and 7.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

King, S. W.; Stammer, C. H. J. Org. Chem. 1981, 46, 4780–4782. doi:10.1021/jo00336a031

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yagisawa, S.; Urakami, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 7557–7560. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(96)01716-9

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sakamoto, S.; Kazumi, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tsukano, C.; Takemoto, Y. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4758–4761. doi:10.1021/ol502198e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Further, reactions of 1 and 2 under different acidic/basic conditions gave complex mixture of products thus precluding extension of work.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nowick, J. S.; Smith, E. M.; Pairish, M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1996, 25, 401–415. doi:10.1039/cs9962500401

Return to citation in text: [1] -

El-Faham, A.; Albericio, F. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6557–6602. doi:10.1021/cr100048w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kishore, R.; Kumar, A.; Balaram, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 8019–8023. doi:10.1021/ja00312a036

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gellman, S. H.; Dado, G. P.; Liang, G. B.; Adams, B. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1164–1173. doi:10.1021/ja00004a016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hehre, W. J.; Radom, L.; Schleyer, P. v. R.; Pople, J. A. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory; John Wiley: New York, NY, U.S.A., 1986.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stewart, J. J. P. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 1173–1213. doi:10.1007/s00894-007-0233-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hille, B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, 3rd ed.; Sinauer: Sunderland, MA, U.S.A., 2001.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Benz, R.; Hancock, R. E. W. J. Gen. Physiol. 1987, 89, 275–295. doi:10.1085/jgp.89.2.275

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Beer, P. D.; Gale, P. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 486–516. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010202)40:3<486::aid-anie486>3.0.co;2-p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bitter, E. E.; Pusch, M., Eds. Chloride movements across cellular membranes; Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology, Vol. 38; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2006.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jentsch, J. J. T.; Stein, V.; Weinrich, F.; Zdebik, A. A. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 503–568. doi:10.1152/physrev.00029.2001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Busschaert, N.; Gale, P. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1374–1382. doi:10.1002/anie.201207535

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Choi, J. Y.; Muallem, D.; Kiselyov, K.; Lee, M. G.; Thomas, P. J.; Muallem, S. Nature 2001, 410, 94–97. doi:10.1038/35065099

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bong, D. T.; Clark, T. D.; Granja, J. R.; Ghadiri, M. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 988–1011. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010316)40:6<988::aid-anie9880>3.0.co;2-n

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ranganathan, D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 919–930. doi:10.1021/ar000147v

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Brea, R. J.; Reiriz, C.; Granja, J. R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1448–1456. doi:10.1039/b805753m

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Martí, I.; Burguete, M. I.; Gale, P. A.; Luis, S. V. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 5150–5158. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201500390

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Schlesinger, P. H.; Ferdani, R.; Liu, J.; Pajewska, J.; Pajewski, R.; Saito, M.; Shabany, H.; Gokel, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 1848–1849. doi:10.1021/ja016784d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Benke, B. P.; Madhavan, N. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7340–7342. doi:10.1039/c3cc44224a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Diemer, V.; Fischer, L.; Kauffmann, B.; Guichard, G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15684–15692. doi:10.1002/chem.201602481

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, A.-F.; Wang, J.-H.; Wang, F.; Jiang, Y.-B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3729–3745. doi:10.1039/b926160p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gorteau, V.; Bollot, G.; Mareda, J.; Perez-Velasco, A.; Matile, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 14788–14789. doi:10.1021/ja0665747

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gorteau, V.; Julliard, M. D.; Matile, S. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 321, 37–42. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2007.10.040

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McNally, B. A.; Koulov, A. V.; Smith, B. D.; Joos, J.-B.; Davis, A. P. Chem. Commun. 2005, 1087–1089. doi:10.1039/b414589e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hussain, S.; Brotherhood, P. R.; Judd, L. W.; Davis, A. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1614–1617. doi:10.1021/ja1076102

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fisher, M. G.; Gale, P. A.; Hiscock, J. R.; Hursthouse, M. B.; Light, M. E.; Schmidtchen, F. P.; Tong, C. C. Chem. Commun. 2009, 3017–3019. doi:10.1039/b904089g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gale, P. A.; Tong, C. C.; Haynes, C. J. E.; Adeosun, O.; Gross, D. E.; Karnas, E.; Sedenberg, E. M.; Quesada, R.; Sessler, J. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3240–3241. doi:10.1021/ja9092693

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sidorov, V.; Kotch, F. W.; Abdrakhmanova, G.; Mizani, R.; Fettinger, J. C.; Davis, J. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2267–2278. doi:10.1021/ja012338e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maulucci, N.; Izzo, I.; Licen, S.; Maulucci, N.; Autore, G.; Marzocco, S.; TecillaDe, P.; De Riccardis, F. Chem. Commun. 2008, 3927–3929. doi:10.1039/b806508j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Davis, J. T.; Okunola, O.; Quesada, R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3843–3862. doi:10.1039/b926164h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brotherhood, P. R.; Davis, A. P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3633–3647. doi:10.1039/b926225n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gale, P. A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 216–226. doi:10.1021/ar100134p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Madhavan, N.; Robert, E. C.; Gin, M. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7584–7587. doi:10.1002/anie.200501625

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Saha, T.; Dasari, S.; Tewari, D.; Prathap, A.; Sureshan, K. M.; Bera, A. K.; Mukherjee, A.; Talukdar, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14128–14135. doi:10.1021/ja506278z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kelly, T. R.; Kim, M. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 7072–7080. doi:10.1021/ja00095a009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dias, C. M.; Li, H.; Valkenier, H.; Karagiannidis, L. E.; Gale, P. A.; Sheppard, D. N.; Davis, A. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 1083–1087. doi:10.1039/c7ob02787g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Salunke, S. B.; Malla, J. A.; Talukdar, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5354–5358. doi:10.1002/anie.201900869

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 54. | Davis, J. T.; Okunola, O.; Quesada, R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3843–3862. doi:10.1039/b926164h |

| 55. | Brotherhood, P. R.; Davis, A. P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3633–3647. doi:10.1039/b926225n |

| 56. | Gale, P. A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 216–226. doi:10.1021/ar100134p |

| 38. | Bong, D. T.; Clark, T. D.; Granja, J. R.; Ghadiri, M. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 988–1011. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010316)40:6<988::aid-anie9880>3.0.co;2-n |

| 9. | Forman, G. S.; Scaffidi, A.; Stick, R. V. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 25–28. doi:10.1071/ch03214 |

| 10. | Scaffidi, A.; Skelton, B. W.; Stick, R. V.; White, A. H. Aust. J. Chem. 2007, 60, 93–94. doi:10.1071/ch06392 |

| 11. | Scaffidi, A.; Skelton, B. W.; Stick, R. V.; White, A. H. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 733–740. doi:10.1071/ch04014 |

| 25. | Nowick, J. S.; Smith, E. M.; Pairish, M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1996, 25, 401–415. doi:10.1039/cs9962500401 |

| 6. | Estevez, J. C.; Estevez, R. J.; Ardron, H.; Wormald, M. R.; Brown, D.; Fleet, G. W. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 8885–8888. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78525-x |

| 7. | Estevez, J. C.; Ardron, H.; Wormald, M. R.; Brown, D.; Fleet, G. W. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 8889–8890. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78526-1 |

| 8. | Estevez, J. C.; Smith, M. D.; Wormald, M. R.; Besra, G. S.; Brennan, P. J.; Nash, R. J.; Fleet, G. W. J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1996, 7, 391–394. doi:10.1016/0957-4166(96)00014-6 |

| 26. | El-Faham, A.; Albericio, F. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6557–6602. doi:10.1021/cr100048w |

| 5. | Maity, P.; Zabel, M.; König, B. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 8046–8053. doi:10.1021/jo701423w |

| 24. | Further, reactions of 1 and 2 under different acidic/basic conditions gave complex mixture of products thus precluding extension of work. |

| 11. | Scaffidi, A.; Skelton, B. W.; Stick, R. V.; White, A. H. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 733–740. doi:10.1071/ch04014 |

| 2. | Bonora, G. M.; Toniolo, C.; Di Blasio, B.; Pavone, V.; Pedone, C.; Benedetti, E.; Lingham, I.; Hardy, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 8152–8156. doi:10.1021/ja00338a025 |

| 3. | Toniolo, C.; Bonora, G. M.; Barone, V.; Bavoso, A.; Benedetti, E.; Di Blasio, B.; Grimaldi, P.; Lelj, F.; Pavone, V.; Pedone, C. Macromolecules 1985, 18, 895–902. doi:10.1021/ma00147a013 |

| 4. | Demizu, Y.; Doi, M.; Kurihara, M.; Maruyama, T.; Suemune, H.; Tanaka, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 2430–2439. doi:10.1002/chem.201102902 |

| 21. | King, S. W.; Stammer, C. H. J. Org. Chem. 1981, 46, 4780–4782. doi:10.1021/jo00336a031 |

| 22. | Yagisawa, S.; Urakami, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 7557–7560. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(96)01716-9 |

| 23. | Sakamoto, S.; Kazumi, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tsukano, C.; Takemoto, Y. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4758–4761. doi:10.1021/ol502198e |

| 19. | Pawar, N. J.; Diederichsen, U.; Dhavale, D. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 11278–11285. doi:10.1039/c5ob01673h |

| 20. | Synthesis of azido dipeptide 5 and tetrapeptide 7 is reported [11] using TsCl in pyridine as an activating agent for the carboxylic group. The same reaction at our hand gave the dark brown coloured product that on purification afforded ≈30% yield while; the use of CMPI as coupling reagent gave pale yellow solid product that on purification gave ≈75% yield of 5 and 7. |

| 17. | Burade, S. S.; Shinde, S. V.; Bhuma, N.; Kumbhar, N.; Kotmale, A.; Rajamohanan, P. R.; Gonnade, R. G.; Talukdar, P.; Dhavale, D. D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 5826–5834. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00661 |

| 18. | Burade, S. S.; Saha, T.; Bhuma, N.; Kumbhar, N.; Kotmale, A.; Rajamohanan, P. R.; Gonnade, R. G.; Talukdar, P.; Dhavale, D. D. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5948–5951. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02942 |

| 17. | Burade, S. S.; Shinde, S. V.; Bhuma, N.; Kumbhar, N.; Kotmale, A.; Rajamohanan, P. R.; Gonnade, R. G.; Talukdar, P.; Dhavale, D. D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 5826–5834. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00661 |

| 18. | Burade, S. S.; Saha, T.; Bhuma, N.; Kumbhar, N.; Kotmale, A.; Rajamohanan, P. R.; Gonnade, R. G.; Talukdar, P.; Dhavale, D. D. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5948–5951. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02942 |

| 21. | King, S. W.; Stammer, C. H. J. Org. Chem. 1981, 46, 4780–4782. doi:10.1021/jo00336a031 |

| 22. | Yagisawa, S.; Urakami, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 7557–7560. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(96)01716-9 |

| 23. | Sakamoto, S.; Kazumi, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tsukano, C.; Takemoto, Y. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4758–4761. doi:10.1021/ol502198e |

| 57. | Madhavan, N.; Robert, E. C.; Gin, M. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7584–7587. doi:10.1002/anie.200501625 |

| 58. | Saha, T.; Dasari, S.; Tewari, D.; Prathap, A.; Sureshan, K. M.; Bera, A. K.; Mukherjee, A.; Talukdar, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14128–14135. doi:10.1021/ja506278z |

| 59. | Kelly, T. R.; Kim, M. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 7072–7080. doi:10.1021/ja00095a009 |

| 60. | Dias, C. M.; Li, H.; Valkenier, H.; Karagiannidis, L. E.; Gale, P. A.; Sheppard, D. N.; Davis, A. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 1083–1087. doi:10.1039/c7ob02787g |

| 61. | Salunke, S. B.; Malla, J. A.; Talukdar, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5354–5358. doi:10.1002/anie.201900869 |

| 13. | Djedovic, N.; Ferdani, R.; Harder, E.; Pajewska, J.; Pajewski, R.; Weber, M. E.; Schlesinger, P. H.; Gokel, G. W. New J. Chem. 2005, 29, 291–305. doi:10.1039/b417091c |

| 14. | García-Fandiño, R.; Amorín, M.; Castedo, L.; Granja, J. R. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3280. doi:10.1039/c2sc21068a |

| 15. | Sakai, N.; Houdebert, D.; Matile, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2003, 9, 223–232. doi:10.1002/chem.200390016 |

| 16. | Zeng, F.; Liu, F.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, S.; Shen, J.; Li, N.; Ren, H.; Zeng, H. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 4826–4830. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01723 |

| 40. | Brea, R. J.; Reiriz, C.; Granja, J. R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1448–1456. doi:10.1039/b805753m |

| 12. | Vangala, M.; Dhokale, S. A.; Gawade, R. L.; Pattuparambil, R. R.; Puranik, V. G.; Dhavale, D. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6874–6878. doi:10.1039/c3ob41462k |

| 12. | Vangala, M.; Dhokale, S. A.; Gawade, R. L.; Pattuparambil, R. R.; Puranik, V. G.; Dhavale, D. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6874–6878. doi:10.1039/c3ob41462k |

| 41. | Martí, I.; Burguete, M. I.; Gale, P. A.; Luis, S. V. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 5150–5158. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201500390 |

| 31. | Hille, B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, 3rd ed.; Sinauer: Sunderland, MA, U.S.A., 2001. |

| 32. | Benz, R.; Hancock, R. E. W. J. Gen. Physiol. 1987, 89, 275–295. doi:10.1085/jgp.89.2.275 |

| 27. | Kishore, R.; Kumar, A.; Balaram, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 8019–8023. doi:10.1021/ja00312a036 |

| 28. | Gellman, S. H.; Dado, G. P.; Liang, G. B.; Adams, B. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1164–1173. doi:10.1021/ja00004a016 |

| 29. | Hehre, W. J.; Radom, L.; Schleyer, P. v. R.; Pople, J. A. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory; John Wiley: New York, NY, U.S.A., 1986. |

| 30. | Stewart, J. J. P. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 1173–1213. doi:10.1007/s00894-007-0233-4 |

| 50. | Fisher, M. G.; Gale, P. A.; Hiscock, J. R.; Hursthouse, M. B.; Light, M. E.; Schmidtchen, F. P.; Tong, C. C. Chem. Commun. 2009, 3017–3019. doi:10.1039/b904089g |

| 51. | Gale, P. A.; Tong, C. C.; Haynes, C. J. E.; Adeosun, O.; Gross, D. E.; Karnas, E.; Sedenberg, E. M.; Quesada, R.; Sessler, J. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3240–3241. doi:10.1021/ja9092693 |

| 52. | Sidorov, V.; Kotch, F. W.; Abdrakhmanova, G.; Mizani, R.; Fettinger, J. C.; Davis, J. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2267–2278. doi:10.1021/ja012338e |

| 53. | Maulucci, N.; Izzo, I.; Licen, S.; Maulucci, N.; Autore, G.; Marzocco, S.; TecillaDe, P.; De Riccardis, F. Chem. Commun. 2008, 3927–3929. doi:10.1039/b806508j |

| 46. | Gorteau, V.; Bollot, G.; Mareda, J.; Perez-Velasco, A.; Matile, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 14788–14789. doi:10.1021/ja0665747 |

| 47. | Gorteau, V.; Julliard, M. D.; Matile, S. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 321, 37–42. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2007.10.040 |

| 48. | McNally, B. A.; Koulov, A. V.; Smith, B. D.; Joos, J.-B.; Davis, A. P. Chem. Commun. 2005, 1087–1089. doi:10.1039/b414589e |

| 49. | Hussain, S.; Brotherhood, P. R.; Judd, L. W.; Davis, A. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1614–1617. doi:10.1021/ja1076102 |

| 38. | Bong, D. T.; Clark, T. D.; Granja, J. R.; Ghadiri, M. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 988–1011. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010316)40:6<988::aid-anie9880>3.0.co;2-n |

| 39. | Ranganathan, D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 919–930. doi:10.1021/ar000147v |

| 40. | Brea, R. J.; Reiriz, C.; Granja, J. R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1448–1456. doi:10.1039/b805753m |

| 41. | Martí, I.; Burguete, M. I.; Gale, P. A.; Luis, S. V. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 5150–5158. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201500390 |

| 42. | Schlesinger, P. H.; Ferdani, R.; Liu, J.; Pajewska, J.; Pajewski, R.; Saito, M.; Shabany, H.; Gokel, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 1848–1849. doi:10.1021/ja016784d |

| 43. | Benke, B. P.; Madhavan, N. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7340–7342. doi:10.1039/c3cc44224a |

| 44. | Diemer, V.; Fischer, L.; Kauffmann, B.; Guichard, G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15684–15692. doi:10.1002/chem.201602481 |

| 45. | Li, A.-F.; Wang, J.-H.; Wang, F.; Jiang, Y.-B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3729–3745. doi:10.1039/b926160p |

| 33. | Beer, P. D.; Gale, P. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 486–516. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010202)40:3<486::aid-anie486>3.0.co;2-p |

| 34. | Bitter, E. E.; Pusch, M., Eds. Chloride movements across cellular membranes; Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology, Vol. 38; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2006. |

| 35. | Jentsch, J. J. T.; Stein, V.; Weinrich, F.; Zdebik, A. A. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 503–568. doi:10.1152/physrev.00029.2001 |

| 36. | Busschaert, N.; Gale, P. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1374–1382. doi:10.1002/anie.201207535 |

| 37. | Choi, J. Y.; Muallem, D.; Kiselyov, K.; Lee, M. G.; Thomas, P. J.; Muallem, S. Nature 2001, 410, 94–97. doi:10.1038/35065099 |

© 2019 Burade et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)

![[1860-5397-15-234-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-234-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)