Abstract

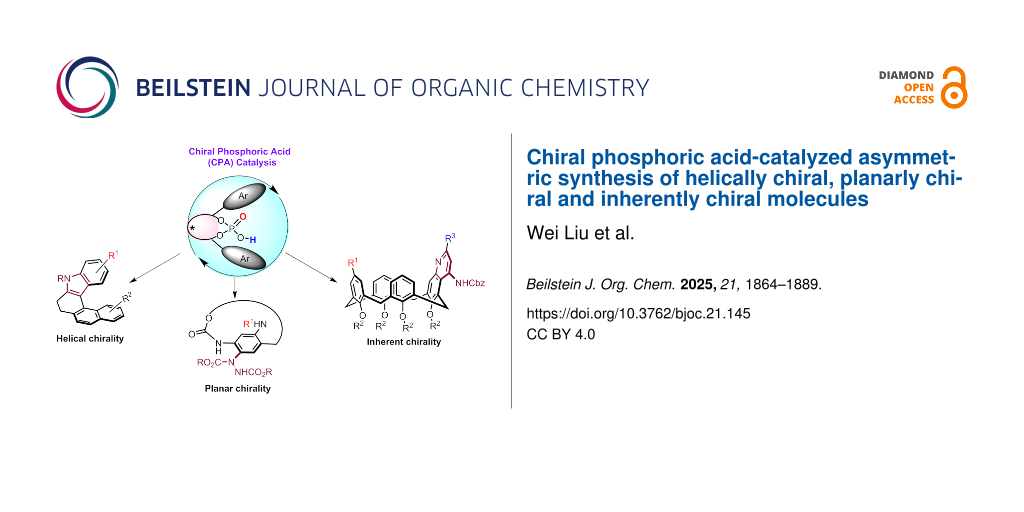

Chiral molecules, distinguished by nonsuperimposability with their mirror image, play crucial roles across diverse research fields. Molecular chirality is conventionally categorized into the following types: central chirality, axial chirality, planar chirality and helical chirality, along with the more recently introduced inherent chirality. As one of the most prominent chiral organocatalysts, chiral phosphoric acid (CPA) catalysis has proven highly effective in synthesizing centrally and axially chiral molecules. However, its potential in the asymmetric construction of other types of molecular chirality has been investigated comparatively less. This Review provides a comprehensive overview of the recent emerging advancements in asymmetric synthesis of planarly chiral, helically chiral and inherently chiral molecules using CPA catalysis, while offering insights into future developments within this domain.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Since the seminal works by Akiyama [1] and Terada [2] et al. in 2004 demonstrated the application of BINOL-derived chiral phosphoric acids (CPAs) in asymmetric Mannich reactions, the past two decades have witnessed the remarkable evolution of CPA catalysis into one of the most versatile platforms for achieving diverse enantioselective transformations [3-8]. CPA catalysts are generally recognized as bifunctional catalysts with two distinct catalytic sites. The OH group on the phosphorus atom functions as a Brønsted acid site, while P=O serves as a Lewis base site, which enables the simultaneous activation of both nucleophiles and electrophiles in one reaction (Figure 1). The chiral properties of the catalysts are derived from the chiral framework of the diol precursors, predominantly axially chiral structures such as BINOL, H8-BINOL, SPINOL and VAPOL scaffolds, which are widely used in the development of CPA catalysts. Furthermore, the ortho-aryl substitutions of the CPA catalyst can efficiently modulate the stereochemical and electronic effects of the CPAs, which establish a chiral microenvironment within the chiral scaffold that governs the stereoselectivity of asymmetric reactions.

Figure 1: General structure of CPAs and selected CPAs with various chiral scaffolds.

Figure 1: General structure of CPAs and selected CPAs with various chiral scaffolds.

Chiral molecules, characterized as three-dimensional structures that are nonsuperimposable with their mirror image, have significant applications in pharmaceutical, agrochemical and asymmetric synthesis as well as materials science, to name a few examples. Molecular chirality is typically classified into four types of chiral elements: central (point) chirality, axial chirality, planar chirality and helical chirality (Figure 2). Moreover, unique forms of chirality originating from the rigid conformation of molecules lacking symmetry, which do not fit into the aforementioned four categories, are termed inherent chirality. Notable examples include inherently chiral calix[4]arenes and saddle-shaped medium-sized cyclic compounds. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis has been recognized as the most straightforward and efficient strategy for synthesizing chiral molecules, with early development primarily targeting compounds featuring stereogenic centers. In the past decade, significant progress has been made in the asymmetric synthesis of diverse axially chiral molecules [9]. However, the exploration of catalytic asymmetric synthesis toward other forms of chiral elements has been relatively limited, with only a few notable instances having emerged recently.

Figure 2: Representative elements of molecular chirality.

Figure 2: Representative elements of molecular chirality.

Similarly, since the initial introduction of CPA catalysts in asymmetric synthesis in 2004, a plethora of asymmetric catalytic reactions to synthesize chiral molecules with stereogenic centers has been developed. Moreover, the rapid advancement of axially chiral molecules in asymmetric synthesis has been made possible by employing CPA catalysis, notably pioneered by Akiyama [10], Tan [11] and others. However, the application of CPA catalysis in the asymmetric synthesis of other forms of molecular chirality has received less attention. While List and co-workers reported the first CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of helically chiral azahelicenes through the Fischer indole synthesis back in 2014 [12], the second CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of helicenes was not achieved until 2023 [13,14]. Similarly, the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of planarly chiral [15] and inherently chiral [16] molecules was not disclosed until 2022. In this Review, we have comprehensively summarized the recent advancements in the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of various distinct chiral elements, encompassing helically, planarly and inherently chiral molecules. The Review is structured based on the various types of chiral elements, presenting a representative substrate scope for each method, showcasing the reaction mechanisms and applications of the chiral products for selected examples.

Review

Helical chirality

Helicenes are a group of rigid polycyclic aromatic compounds composed of ortho-fused aromatic (hetero)cyclic rings, with their helically twisted conformation enforced by steric hindrance between terminal aromatic rings [17]. Despite lacking asymmetric stereogenic centers, this nonplanar scaffold exhibits intrinsic P/M chirality due to the helical arrangement of the π-extended skeleton. Renowned for their high thermal stability and structural rigidity, chiral helicenes have emerged as prominent molecular platforms in various applications, such as circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) materials, chiral liquid crystals and asymmetric catalysis. Currently, the asymmetric catalytic synthesis of helicenes predominantly revolves around transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric annulation reactions, including the asymmetric [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of aryl-substituted polyynes and hydroarylation of alkynes [18,19]. In contrast, the application of asymmetric organocatalysis for enantioselective synthesis of chiral helicenes remains relatively underdeveloped compared to transition metal-catalyzed approaches [20].

In 2014, List and co-workers reported the pioneering CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of helically chiral molecules, which also marked the first organocatalyzed asymmetric synthesis of such compounds [12]. By employing a CPA-catalyzed asymmetric Fischer indolization reaction of hydrazine 1 and polycyclic ketone 2, they achieved the efficient asymmetric synthesis of various helically chiral azahelicenes 3 (Scheme 1). To address the inherent length-scale challenges of molecular helicene frameworks, the authors designed and synthesized novel CPAs bearing extended π-substituents at the ortho-positions. The dual hydrogen-bonding interactions were critical for this reaction, ensuring that the reaction proceeded within the chiral pocket of the CPA catalyst. Moreover, the authors proposed that the extended π-substituents at the ortho-positions of CPA could engage in π–π-stacking interactions with the enehydrazine intermediate, which is essential for achieving high levels of stereocontrol. Using the optimal catalyst CPA 1, a series of aza[6]helicenes 3a,b was synthesized with excellent enantioselectivity and high yield. However, this method demonstrated notably reduced efficiency and stereoselectivity for the more sterically demanding aza[5]helicene 3c and aza[7]helicenes 3d–f. Furthermore, the authors expanded this methodology to a double Fischer indolization reaction between hydrazine 1i and ketone 2i, which yielded diaza[8]helicene 4 with moderate yield and high enantioselectivity after chloranil-mediated dehydrogenation.

Scheme 1: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of azahelicenes via Fischer indole synthesis.

Scheme 1: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of azahelicenes via Fischer indole synthesis.

Despite the early demonstration of CPA catalysis in synthesizing chiral helicenes, the next instance of CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of helicenes was not achieved until 2023. Employing a sequential CPA-catalyzed asymmetric Povarov reaction and oxidative aromatization process, in 2023 our group reported the asymmetric synthesis of various azahelicenes 8 from polycyclic arylamines 5, dienamides 6 and aldehydes 7 (Scheme 2) [13]. This methodology demonstrates a broad substrate scope, enabling the efficient asymmetric synthesis of diverse aza[5]helicenes 8a–d and aza[4]helicene 8e from various aldehydes with high enantioselectivity. In addition, dienamides were found to be compatible with this method, albeit requiring a switch to CPA 3 as the optimal catalyst, which generated the 1-enamide-substituted azahelicenes 8f,g, with significant potential for diverse derivatizations. Based on experimental and computational studies, the origin of helical chirality in this method was elucidated. We proposed that the asymmetric Povarov reaction would generate a pair of diastereomeric tetrahydroquinoline derivatives displaying helical conformation, with a modest energetic barrier for interconversion. However, steric repulsion between the C-1 substitutions and the terminal arene moieties in the M-conformational diastereomer resulted in the P-conformational diastereomer being thermodynamically favored. This led to the formation of (P)-helicene products following DDQ-mediated dehydrogenation.

Scheme 2: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of azahelicenes via sequential Povarov reaction and oxidative aromatization.

Scheme 2: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of azahelicenes via sequential Povarov reaction and oxidative ar...

Almost simultaneously, the Li group independently reported the asymmetric synthesis of chiral quinohelicenes using a similar sequential asymmetric Povarov reaction and oxidative aromatization strategy [14]. In their study, they employed 3-vinylindoles 10 in the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric Povarov reaction with polycyclic arylamines 9 and various aromatic aldehydes 11, resulting in a range of quinoline-containing azahelicenes 12 with moderate yield and excellent enantioselectivity after DDQ-mediated oxidative aromatization (Scheme 3). Notably, they not only expanded the substrate scope to encompass various aldehydes and 3-vinylindoles but also conducted extensive structural modifications on the polycyclic arylamine components, which enabled the asymmetric synthesis of azahelicenes with diverse frameworks, including the chromene- and furan-containing quinohelicenes 12d,e, respectively. They also conducted a thorough evaluation of the stability of the helical chirality across the synthesized quinohelicenes, indicating a high racemization barrier.

Scheme 3: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of azahelicenes via sequential Povarov reaction involving 3-vinylindoles and oxidative aromatization.

Scheme 3: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of azahelicenes via sequential Povarov reaction involving 3-viny...

In 2024, our group further extended the CPA-catalyzed sequential Povarov reaction and aromatization strategy by using 2-vinylphenols 14 as the olefin component, which facilitated the asymmetric synthesis of substituted [5]- and [6]pyridohelicenes 15 with ortho-phenolic substituents in position C1 with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 4) [21]. Notably, utilizing one equivalent of DDQ for semioxidation of the tetrahydroquinoline product of the Povarov reaction produced the imine 16a which, upon treatment with Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 and KHMDS, led to furan ring formation and the generation of hetero[7]helicene 17a while maintaining the stereochemical configuration. Through this methodology, a range of elongated [7]- and [8]heterohelicenes 17b–d incorporating both furan and pyridine moieties were successfully synthesized with high enantioselectivity. These compounds would be challenging to access using alternative asymmetric methods.

Scheme 4: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of heterohelicenes via sequential Povarov reaction involving 2-vinylphenols and aromatization.

Scheme 4: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of heterohelicenes via sequential Povarov reaction involving 2-v...

In 2025, our group disclosed a highly efficient catalytic enantioselective double annulation approach for the asymmetric synthesis of hetero[7]helicenes [22]. By employing a sequential CPA-catalyzed three-component double Povarov reaction involving a pentacyclic diamine substrate 18, enamide 6a and various aldehydes 7, followed by oxidative aromatization, a range of bispyridine-containing hetero[7]helicenes was produced with good yield and excellent enantioselectivity (Scheme 5). Notably, two distinct oxidative aromatization methods have been developed to yield diverse heterohelicene products. For instance, using DDQ as an oxidant selectively delivered hetero[7]helicenes 19 with monoamido substitution at the peri-positions, while utilizing MnO2 as an oxidant selectively yielded heterohelicenes 20 with bisamido substitution at the peri-positions.

Scheme 5: Diverse enantioselective synthesis of hetero[7]helicenes via a CPA-catalyzed double annulation strategy.

Scheme 5: Diverse enantioselective synthesis of hetero[7]helicenes via a CPA-catalyzed double annulation stra...

In 2024, Zhou, Chen and co-workers disclosed an efficient method for the asymmetric synthesis of indolohelicenoids through a sequential enantioselective annulation, followed by an eliminative aromatization sequence [23]. The CPA-catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 2]-cycloaddition of cycloenecarbamates 21 and carbalkoxy-substituted azonaphthalenes 22 produced the hexacyclic products 23' with two contiguous stereogenic centers, which then underwent an eliminative aromatization process to yield various indolohelicenoids 23 with excellent enantioselectivity (Scheme 6). The helical chirality of the products 23 was believed to stem from a notably stereospecific central-to-helical chirality conversion process, maintaining high enantioselectivity even when the eliminative aromatization occurred without the CPA catalyst. Notably, indolohelicenoid 23e could effectively be converted into the fully aromatic indolohelicene 24e under DDQ-mediated oxidative conditions without compromising the enantiopurity of the compound.

Scheme 6: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of indolohelicenoids through enantioselective cycloaddition and eliminative aromatization sequence.

Scheme 6: CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of indolohelicenoids through enantioselective cycloaddition and ...

Kinetic resolution stands as one of the most practical and efficient strategies for accessing chiral compounds. Starting from racemic starting materials, this method entails selective conversion of one enantiomer facilitated by a chiral catalyst, yielding enantioenriched products and allowing for the recovery of unreacted substrate with a high level of enantiopurity [24,25]. While CPAs have been extensively utilized in kinetic resolution of centrally chiral [26-28] and axially chiral compounds [29], their application in the kinetic resolution of helically chiral compounds remains largely unexplored.

In 2024, Liu and co-workers developed an effective method for catalytic kinetic resolution of racemic helical polycyclic phenols through an organocatalyzed enantioselective dearomative amination reaction [30]. The racemic polycyclic phenol derivatives 25, which exist as single diastereomers featuring both central chirality and helical chirality, were readily prepared through a [3 + 3]-cycloaddition reaction. By employing the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric electrophilic amination reaction with azodicarboxylate on the phenol moiety, efficient kinetic resolution of 25 proceeded to yield both the amination products 26 and the recovered starting material with high enantioselectivity, with an s-factor up to >259 (Scheme 7). Notably, this reaction did not produce the typical arene C–H amination products but instead the dearomative amination products 26, which is believed to be due to the significant steric hindrance surrounding the amination site that impeded the subsequent aromatization process. Moreover, the terminal ring of the polycyclic phenol substrates was not limited to a pyranoid moiety as helical polycyclic phenols incorporating a furan ring also efficiently yielded both the dearomatized amination product (P,R,R)-28a and the recovered enantioenriched phenolic compound (M,R)-27a with high enantioselectivity.

Scheme 7: Kinetic resolution of helical polycyclic phenols via CPA-catalyzed enantioselective aminative dearomatization reaction.

Scheme 7: Kinetic resolution of helical polycyclic phenols via CPA-catalyzed enantioselective aminative dearo...

In 2025, Cai, Ji and co-workers reported a practical approach for the kinetic resolution of racemic aza[6]helicenes through CPA-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation [31]. Commencing with the readily available racemic pyrido[6]helicene 29, the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation employing Hantzsch ester HEH-1 as the reductant afforded both helically chiral tetrahydroquinoline derivatives (M)-30 and the recovered aza[6]helicene starting material (P)-29 with good to high enantioselectivity, achieving an s-factor of up to 121 (Scheme 8). Moreover, by leveraging the synthesized enantioenriched aza[6]helicene 29a and tetrahydro[6]helicene 30a as chiral building blocks, a series of helically chiral organocatalysts and ligands could be easily prepared, such as the helically chiral pyridine N-oxide 31a and helically chiral monophosphine ligands 31b,c, whose potential applications in catalytic asymmetric reactions have also been showcased.

Scheme 8: Kinetic resolution of azahelicenes via CPA-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation.

Scheme 8: Kinetic resolution of azahelicenes via CPA-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation.

Planar chirality

Planarly chiral cyclophanes, a unique class of macrocyclic compounds featuring planar chirality, can be found in various natural products and are widely utilized in asymmetric catalysis, host–guest chemistry and materials science [32]. These macrocycles typically consist of a substituted aromatic ring and a macrocyclic side chain (ansa chain), with the planar chirality arising from the restricted flipping of the substituted aromatic ring caused by steric constraints imposed by the ansa chain. Recent advances in asymmetric catalytic synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles have attracted significant attention, leading to the development of several distinctive strategies, such as (dynamic) kinetic resolution and asymmetric macrocyclizations [33-36].

In 2022, our group reported the enantioselective synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles through a dynamic kinetic resolution approach [15]. Despite bearing an amino group on the phenyl ring, the configuration of the macrocyclic paracyclophane 32 was found to be unstable at room temperature. Consequently, by employing a CPA-catalyzed asymmetric electrophilic amination reaction of the aniline moiety with azodicarboxylates [37,38], the introduction of a bulky hydrazine group restricted the free flipping of the benzene ring, leading to the formation of planar chiral macrocycle 33 with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 9). Substrate scope studies demonstrated the successful construction of planarly chiral macrocycles with 12- to 14-membered ansa chains with high enantioselectivity when using NH2 as the directing group (see 33a,b). However, extending the ansa chain to 15 members led to the loss of planar chirality due to insufficient steric hindrance to restrict the benzene ring flipping (see 33c). Notably, the use of a bulkier NHBn directing group allowed for the extension of the ansa chain to 15–19 members (see 33d,e), while preserving planar chirality and functional group compatibility. Remarkably, the chiral paracyclophane product 33a could be directly used as a planarly chiral primary amine catalyst in the asymmetric electrophilic amination reaction of aldehyde 34, which yielded the α-amination product 35 with high enantioselectivity.

Scheme 9: Asymmetric synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles via CPA-catalyzed electrophilic aromatic amination.

Scheme 9: Asymmetric synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles via CPA-catalyzed electrophilic aromatic aminat...

In 2022, our group disclosed an enantioselective macrocyclization protocol for the asymmetric synthesis of planarly chiral paracyclophanes [39]. Commenced with a macrocyclization precursor 36 featuring both a hydroxy group and an allenamide moiety, the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric intramolecular addition led to the successful construction of planarly chiral macrocycles 37 (Scheme 10). This method demonstrated broad substrate compatibility, accommodating sterically demanding dibromo and various dialkynyl substitutions on the phenyl ring. A series of planarly chiral macrocycles with ansa chains ranging from 15 to 18 members was synthesized with good to high enantioselectivity, albeit with moderate yield. Significantly, thermal stability studies demonstrated high configurational stability of these planarly chiral macrocycles, a critical feature that enhances their potential for future utility.

Scheme 10: Enantioselective synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles via CPA-catalyzed macrocyclization.

Scheme 10: Enantioselective synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles via CPA-catalyzed macrocyclization.

In 2023, Zhao and co-worker reported the asymmetric synthesis of planarly chiral paracyclophanes through either catalytic kinetic resolution or dynamic kinetic resolution [40]. The authors designed and synthesized a series of benzaldehyde-containing macrocyclic cyclophanes 38. Therein, they achieved the construction of planar chirality through CPA-catalyzed asymmetric reductive amination with arylamines using Hantzsch ester HEH-2 as the hydrogen transfer reagent (Scheme 11). Notably, when starting from macrocyclic substrates featuring relatively shorter ansa chains (11–14 members, see 38a–c), highly efficient kinetic resolution was achieved, resulting in both recovered (Rp)-38 and reductive amination products (Sp)-39 with high enantioselectivity. Conversely, employing macrocyclic paracyclophane with longer ansa chains (≥15 members) enabled efficient dynamic kinetic resolution due to the instable planar chirality of the substrates, which produced the planarly chiral macrocycles with high yield and enantioselectivity (up to 98% yield and 99% ee).

Scheme 11: (Dynamic) kinetic resolution of planarly chiral paracyclophanes via CPA-catalyzed asymmetric reductive amination.

Scheme 11: (Dynamic) kinetic resolution of planarly chiral paracyclophanes via CPA-catalyzed asymmetric reduct...

In 2025, Li and co-workers utilized analogous racemic benzaldehyde-containing paracyclophanes as substrates and accomplished their efficient kinetic resolution through catalytic asymmetric allylation [41]. Employing CPA/Bi(OAc)3 as a combined catalyst, the asymmetric allylation of racemic 40 with allylboronic acid pinacol ester (41) led to efficient kinetic resolution, yielding the recovery of (Sp)-40 with high enantiopurity (Scheme 12). Notably, the allylation products 42, possessing both planar chirality and central chirality, were produced with high enantioselectivity and diastereoselectivity. Previously, they have been challenging to access in an asymmetric one-step reaction. A range of paracyclophanes with diverse substitutions, including aryl, heteroaryl, alkynyl and bromo substitutions, along with a varying length of the ansa chain, were found to be amenable to this method, resulting in kinetic resolution with an exceptional performance.

Scheme 12: Kinetic resolution of macrocyclic paracyclophanes through CPA/Bi-catalyzed asymmetric allylation.

Scheme 12: Kinetic resolution of macrocyclic paracyclophanes through CPA/Bi-catalyzed asymmetric allylation.

In 2025, Zhou and co-workers disclosed the asymmetric synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles via CPA-catalyzed atroposelective macrocyclization [42]. The authors devised and prepared a series of indole-based hydroxy-substituted carboxylic acid substrates 43 which, upon treatment with ynamide 44, yielded the vinyl acetate intermediate INT-A (Scheme 13). Subsequently, the one-pot CPA-catalyzed intramolecular esterification of this intermediate afforded the planarly chiral macrocycles 45 with good yield and high enantioselectivity. Investigations of the substrate scope revealed the compatibility of the method with various substitutions on the indole moiety and modifications to the length of the ansa chain, which produced planarly chiral macrocycles with up to 99% ee. In addition, this method was successfully employed for the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of planarly chiral macrocyclic paracyclophane 47 from the corresponding hydroxy-substituted carboxylic acid substrate 46. Notably, the authors also demonstrated the application of this method in the enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral C–N and N–N atropisomers, highlighting the versatility of this method in the asymmetric synthesis of diverse chiral molecular structures.

Scheme 13: Enantioselective synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles via CPA-catalyzed coupling of carboxylic acids with alcohols via ynamide mediation.

Scheme 13: Enantioselective synthesis of planarly chiral macrocycles via CPA-catalyzed coupling of carboxylic ...

Substituted [2.2]paracyclophanes represent another class of conformationally rigid, planarly chiral molecules, which have emerged as versatile scaffolds for developing chiral catalysts, ligands and functional materials. In 2023, our group reported the first catalytic kinetic resolution of racemic amido[2.2]paracyclophanes through a CPA-catalyzed asymmetric aromatic amination reaction [43]. Treating the racemic N-Boc-substituted [2.2]paracyclophane 48a with dibenzyl azodicarboxylate (0.7 equiv) in the presence of CPA 6 (10 mol %) led to efficient kinetic resolution, yielding both the para-C–H amination product 49a and the recovered starting material (Rp)-48a with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 14). Notably, subjecting 49a to strongly basic conditions resulted in dehydrazidation to give (Sp)-48a, and thus enabling facile access to both amido[2.2]paracyclophane enantiomers. Moreover, this method demonstrated broad substrate generality, which enabled the efficient kinetic resolution of various disubstituted amido[2.2]paracyclophanes, including the pseudo-geminal- (see 48b,c), pseudo-ortho- (see 48d,e), pseudo-meta- (48f,g) and pseudo-para-substituted ones (see 48h,i). Furthermore, this method could also be utilized for the enantioselective desymmetrization of achiral diamido-substituted [2.2]paracyclophane substrate 50, delivering the C–H amination product 51 with excellent enantioselectivity (99% ee).

Scheme 14: Kinetic resolution of substituted amido[2.2]paracyclophanes via CPA-catalyzed asymmetric electrophilic amination.

Scheme 14: Kinetic resolution of substituted amido[2.2]paracyclophanes via CPA-catalyzed asymmetric electrophi...

Inherent chirality

The concept of inherent chirality was first coined by Böhmer and co-workers in 1994 to describe the chirality originating from the asymmetric arrangement of achiral substituents within calixarene frameworks [44]. This term was later extended to encompass other conformationally rigid chiral molecules that do not fit into conventional categories of central, axial, planar or helical chirality, such as saddle-shaped, medium-sized cyclic compounds [45] and others [46]. These structurally distinct chiral molecules have received considerable research attention due to their broad range of potential applications in chiral recognition, sensing and asymmetric catalysis. However, achieving the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of these inherently chiral molecules remains highly challenging owing to their unique three-dimensional structures and relatively large size [47,48].

In 2024, both our group [49] and the Liu group [50] independently reported the asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes through an enantioselective desymmetrization strategy. Starting from the achiral aniline-containing calix[4]arenes 52, we employed the CPA 11-catalyzed asymmetric Povarov reaction [51] with enamide 6a and various aldehydes 7 to break the symmetry of substrates 52, which was followed by a one-pot oxidative aromatization mediated by DDQ to yield the quinoline-containing inherently chiral calix[4]arenes 53 (Scheme 15). Notably, the prochiral calix[4]arenes bearing a disubstitution pattern on the 1,3-phenyl rings (see 53d) or 1,3-diamino substitution (see 53e) on the calix[4]arene scaffold were also amenable to this method, which yielded a series of structurally diverse novel quinoline-containing inherently chiral calix[4]arenes. Moreover, by using CPA 4 as the optimal catalyst, the sequential asymmetric Povarov reaction of 52a with dienamide 6b and benzaldehyde 7a, followed by oxidative aromatization, led to the formation of enamide-substituted, quinoline-containing inherently chiral calix[4]arene 54a, whose enamide moiety could undergo diverse derivatizations. Analogously, the Liu group achieved the asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral quinoline-containing calix[4]arenes 53 through the same approach, using (S)-CPA 12 as the optimal catalyst.

Scheme 15: Enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via sequential CPA-catalyzed Povarov reaction and aromatization.

Scheme 15: Enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via sequential CPA-catalyzed Povarov...

In 2025, our group presented another example of an asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes using a CPA-catalyzed enantioselective desymmetrization strategy [52]. Commencing with phenol-containing prochiral calix[4]arenes 55, the CPA 3-catalyzed asymmetric ortho-C–H amination with electrophilic azo reagents 56 effectively broke the symmetry of the substrate, leading to the formation of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes 57 with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 16). Notably, with the use of acyclic azodicarboxylate as amination reagent, the products exhibited both inherent chirality and intriguing C–N axial chirality (see 57a). This method demonstrates excellent substrate compatibility, accommodating various calix[4]arenes with 1,3-phenyl ring disubstitution patterns (see 57c,d) and diphenol-containing calix[4]arenes (see 57e,f). The aminated chiral calix[4]arene products underwent diverse derivatizations due to the abundance of functional groups present. Moreover, the potential applications of these unique inherently chiral calix[4]arenes have also been showcased. For instance, facile derivatizations of 57a afforded the inherently chiral meta-amino-substituted calix[4]arene 58 and the corresponding aniline N-oxide 59. Our study suggested that inherently chiral calix[4]arene 58 could successfully be used as a chiral organocatalyst in the asymmetric amination of aldehyde 34, whereas inherently chiral aniline N-oxide 59 showed promise in the chiral recognition of mandelic acid.

Scheme 16: Asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via CPA-catalyzed aminative desymmetrization.

Scheme 16: Asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral calix[4]arenes via CPA-catalyzed aminative desymmetrizati...

In 2024, Tong, Wang and co-workers disclosed an efficient method for synthesizing inherently chiral heterocalix[4]arenes through an asymmetric macrocyclization strategy [53]. Starting from the linear precursor 60 bearing two triazine moieties, the intramolecular SNAr reaction catalyzed by CPA 13 (30 mol %) led to macrocyclization, which produced the inherently chiral N3,O-calix[2]arene[2]triazines 61 with high enantioselectivity, albeit in moderate yield (Scheme 17). The addition of K2CO3 after 12 hours improved the enantioselectivity of this reaction by scavenging the HCl produced during the SNAr reaction, which was believed to potentially promote the nonenantioselective background macrocyclization reaction. Notably, these inherently chiral heterocalix[4]arenes displayed a distinctive 1,3-alternate conformation, notably differing from the typical cone conformation of the conventional calix[4]arenes. Moreover, unlike previously documented examples, the inherent chirality of these products arises from the difference of just one heteroatom (O and NH) in the linking positions of the heterocalix[4]arenes, which may pave new avenues for designing and synthesizing inherently chiral macrocycles.

Scheme 17: Asymmetric synthesis of chiral heterocalix[4]arenes via CPA-catalyzed intramolecular SNAr reaction.

Scheme 17: Asymmetric synthesis of chiral heterocalix[4]arenes via CPA-catalyzed intramolecular SNAr reaction.

Cyclic molecules smaller than calix[4]arenes that possess a rigid nonplanar conformation can also exhibit inherent chirality. In 2023, Luo, Zhu and co-workers reported the efficient asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral eight-membered N-heterocycle 6,7-diphenyldibenzo[e,g][1,4]diazocines (DDDs), which displayed a rigid saddle-shaped configuration [16]. Starting from readily available [1,1'-biphenyl]-2,2'-diamines 62 and benzyl compounds 63, the asymmetric cyclocondensation between these two components enabled by CPA catalysts yielded the inherently chiral DDDs 64 with good to high enantioselectivity (Scheme 18). While a number of reactions did not initially yield satisfactory enantioselectivity, facile phase separation during the workup process removed the less soluble racemic products, which resulted in the isolation of chiral products with exceptional enantiopurity. Moreover, this method accommodated [1,1'-biphenyl]-2,2'-diamines 62 with ortho-substitutions, which underwent either dynamic kinetic resolution or kinetic resolution to produce chiral substituted DDD products 64e. Moreover, the authors showcased the facile derivatization of dimethoxy-substituted chiral DDD 64f into various DDD-based chiral ligands, such as the phosphoramidites 65, phosphoric acid as well as monophosphine ligands and diphosphine ligands 66. Notably, the applications of these novel inherently chiral ligands have been explored. For example, they demonstrated excellent enantioselectivity control in some asymmetric reactions, such as the Rh/diphosphine ligand 66-catalyzed asymmetric addition reaction between cyclic enone and arylboronic acid.

Scheme 18: Enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral DDDs via CPA-catalyzed cyclocondensation.

Scheme 18: Enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral DDDs via CPA-catalyzed cyclocondensation.

In 2024, our group reported the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of saddle-shaped inherently chiral 9,10-dihydrotribenzoazocines via CPA-catalyzed kinetic resolution and dynamic kinetic resolution strategies [54]. By leveraging the reactivity of the aniline moiety in 9,10-dihydrotribenzoazocines 68, the CPA 16-catalyzed enantioselective para-selective C–H amination reaction with dibenzyl azodicarboxylate (0.8 equiv) resulted in efficient kinetic resolution, which yielded both the C–H amination product 69 and recovered (+)-68 with high enantioselectivity (see 68a–c, Scheme 19). Moreover, this method was also applicable to the kinetic resolution of racemic 10-substituted 9,10-dihydrotribenzoazocines featuring both inherent and central chirality, delivering excellent kinetic resolution performance (see 68d–g). During our studies, we serendipitously found that the imine-containing eight-membered azaheterocycles 70, derived from the oxidative dehydrogenation of 68, displayed unexpectedly low configurational stability. Consequently, we developed a more efficient dynamic kinetic resolution protocol for the asymmetric synthesis of inherently chiral 68. This method involved the CPA 17-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogen transfer reaction of racemic 70 using Hantzsch ester HEH-3 as the reductant, which enabled the asymmetric synthesis of some inherently chiral substituted 9,10-dihydrotribenzoazocines that had been challenging to access through the aminative dearomatization method (see 68h,i).

Scheme 19: Asymmetric synthesis of saddle-shaped inherently chiral 9,10-dihydrotribenzoazocines via CPA-catalyzed (dynamic) kinetic resolution.

Scheme 19: Asymmetric synthesis of saddle-shaped inherently chiral 9,10-dihydrotribenzoazocines via CPA-cataly...

In 2024, our group reported a convenient method for the asymmetric synthesis of saddle-shaped inherently chiral dibenzo[b,f][1,5]diazocines 72 via CPA catalysis [55]. In the presence of CPA 7 (10 mol %) and the corresponding 2-acylaniline 73 (20 mol %) as co-catalysts, the asymmetric dimerization of 2-acylbenzo isocyanates 71 allowed access to inherently chiral eight-membered azaheterocycles 72 with moderate to good enantioselectivity, along with the release of CO2 (Scheme 20). While the enantioselectivity using certain substrates was initially unsatisfactory, simple phase separation significantly enhanced the enantiopurity of the products by removing the less soluble racemic products. Detailed studies were conducted to explore the reaction mechanism, focusing specifically on the role of the 2-acylanilines 73 as co-catalysts. Based on the experimental results and previous research, a plausible mechanism was proposed. Isomerization of substrates 71 yielded the cyclic intermediate INT-B, which then underwent addition with aniline co-catalyst 73 to form INT-C. The CPA-enabled release of CO2 from INT-C yielded the imine-containing intermediate INT-D, which underwent iterative addition with INT-B, followed by release of CO2 to afford INT-E. The CPA-catalyzed cyclization of INT-E through the dual hydrogen bonding activation transition state TS-1 afforded the eight-membered heterocycle INT-F with a stereogenic center. Through the elimination of aniline 73, the saddle-shaped dibenzo[1,5]diazocine 72 was produced via a central-to-inherent chirality transfer process. Notably, while only the amino group of the co-catalysts was shown to engage in the catalytic cycle, the 2-acyl group of 73 was believed to participate in hydrogen bonding interactions with the substrate and the CPA catalyst, playing additional crucial roles.

Scheme 20: Enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral saddle-shaped dibenzo[b,f][1,5]diazocines via CPA-catalyzed dimerization of 2-acylbenzo isocyanates.

Scheme 20: Enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral saddle-shaped dibenzo[b,f][1,5]diazocines via CPA-c...

In addition to various saddle-shaped eight-membered azaheterocycles, conformationally rigid seven-membered cyclic compounds can also exhibit inherent chirality. In 2017, Antilla et al. developed the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric condensation of 4-substituted cyclohexanones with O-arylhydroxylamines, which yielded axially chiral cyclohexylidene oxime ethers with high enantioselectivity [56]. In 2024, through the utilization of this method, Liu and co-workers disclosed the enantioselective synthesis of inherently chiral 7-membered tribenzocycloheptene oximes 76 through CPA 18-catalyzed asymmetric condensation between 7-membered cyclic ketones 74 and hydroxylamines 75 (Scheme 21) [57]. High to excellent yield and enantioselectivity were achieved for the inherently chiral products when using a range of substituted arylhydroxylamines (see 76a–c). The racemization barrier of the product 76a was determined to be 110.5 kJ/mol, which suggested the relative instability of the configuration of these structurally unique products compared to the eight-membered inherently chiral compounds. Moreover, unsymmetrical substituted cyclic ketones 74 were investigated under the standard conditions, which produced a pair of diastereomers with poor diastereoselectivity while maintaining high enantioselectivity for both diastereomers (see 76d–g). Furthermore, the authors have investigated the asymmetric condensation using other seven-membered cyclic ketones (see 77a) as well as the coupling with alkylhydroxylamine (see 77b), tosylhydrazide (see 77c) and N-aminoindole (see 77d), which all produced the inherently chiral products with moderate to good enantioselectivity, albeit requiring the use of different CPA catalysts.

Scheme 21: Enantioselective synthesis of inherent chiral 7-membered tribenzocycloheptene oximes via CPA-catalyzed condensation.

Scheme 21: Enantioselective synthesis of inherent chiral 7-membered tribenzocycloheptene oximes via CPA-cataly...

Conclusion

The increasing number of applications of non-centrally-chiral molecules, including helically chiral, planarly chiral and inherently chiral molecules across diverse research fields, has spurred considerable research focus toward the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of these unique chiral molecules. While methods for the asymmetric synthesis of these chiral molecules remain relatively underexplored compared to the enantioselective synthesis of centrally and axially chiral compounds, significant progress has been made in these fields in recent years. Among numerous chiral catalysts, CPAs have emerged as key players in the asymmetric synthesis of these structurally unique chiral molecules, owing to their diverse catalytic abilities, precise stereoselectivity control and mild reaction conditions. In this Review, we systematically summarized the advancements in the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of helically chiral, planarly chiral and inherently chiral molecules. Various CPA-catalyzed reactions, such as cyclizations, aromatic substitutions and condensations, along with asymmetric synthesis strategies, such as enantioselective desymmetrization and (dynamic) kinetic resolution, have been employed for the asymmetric construction of these chiral elements.

Despite remarkable progress and significant potential in the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of these unique chiral molecules, some current limitations and challenges still need to be addressed, particularly enhancing the efficiency of the methods and expanding the structural diversity of the products. Firstly, the chiral products generated through CPA-catalyzed methods are still relatively simple. For instance, in terms of helically chiral helicenes, typically, only the relatively shorter [5]helicenes have been produced, while the more complex, longer helicenes and multihelicenes have not yet been successfully synthesized through CPA-catalyzed asymmetric methods. Secondly, asymmetric synthetic strategies based on presynthesized three-dimensional molecular structures are commonly employed, such as enantioselective desymmetrization and (dynamic) kinetic resolution. While these strategies have proven effective, the efficiency of these methods may not be considered highly satisfactory due to the requirement to prepare relatively complex substrates. Therefore, there is a high demand for the development of more efficient asymmetric methods through which molecular structures can be directly constructed while achieving high enantioselectivity. Overall, with the recent rapid advancements of CPA catalysis, along with the utilization of CPA catalysts in asymmetric radical chemistry, transition metal-catalyzed reactions and photoredox chemistry, we envision that CPA catalysts will continue to play a central role in the future asymmetric synthesis of helically chiral, planarly chiral and inherently chiral molecules.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data was generated or analyzed in this study.

References

-

Akiyama, T.; Itoh, J.; Yokota, K.; Fuchibe, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1566–1568. doi:10.1002/anie.200353240

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Uraguchi, D.; Terada, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5356–5357. doi:10.1021/ja0491533

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Akiyama, T. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5744–5758. doi:10.1021/cr068374j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Terada, M. Synthesis 2010, 1929–1982. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1218801

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Parmar, D.; Sugiono, E.; Raja, S.; Rueping, M. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9047–9153. doi:10.1021/cr5001496

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Akiyama, T.; Mori, K. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9277–9306. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rahman, A.; Lin, X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 4753–4777. doi:10.1039/c8ob00900g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, X.; Song, Q. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018, 29, 1181–1192. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.01.045

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheng, J. K.; Xiang, S.-H.; Li, S.; Ye, L.; Tan, B. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4805–4902. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01306

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mori, K.; Ichikawa, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Shibata, Y.; Yamanaka, M.; Akiyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3964–3970. doi:10.1021/ja311902f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Da, B.-C.; Xiang, S.-H.; Li, S.; Tan, B. Chin. J. Chem. 2021, 39, 1787–1796. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202000751

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kötzner, L.; Webber, M. J.; Martínez, A.; De Fusco, C.; List, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5202–5205. doi:10.1002/anie.201400474

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liu, W.; Qin, T.; Xie, W.; Zhou, J.; Ye, Z.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303430. doi:10.1002/anie.202303430

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, C.; Shao, Y.-B.; Gao, X.; Ren, Z.; Guo, C.; Li, M.; Li, X. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3380. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39134-9

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wang, D.; Shao, Y.-B.; Chen, Y.; Xue, X.-S.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202201064. doi:10.1002/anie.202201064

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Peng, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, T.; Cheng, S.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Gan, C.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 982–993. doi:10.31635/ccschem.022.202201901

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Shen, Y.; Chen, C.-F. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1463–1535. doi:10.1021/cr200087r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.-G.; Shi, F. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 3077–3111. doi:10.1016/j.checat.2022.10.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, W.; Qin, T.; Xie, W.; Yang, X. Chem. – Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202202369. doi:10.1002/chem.202202369

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, Q.; Tang, Y.-P.; Zhang, C.-G.; Wang, Z.; Dai, L. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 16256–16265. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c05345

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xie, W.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Qin, T.; Yang, X. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 101993. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2024.101993

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qin, T.; Xie, W.; Liu, W.; Yang, X. Org. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 1417–1424. doi:10.1039/d4qo02188f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, W.-L.; Zhang, R.-X.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202318021. doi:10.1002/anie.202318021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vedejs, E.; Jure, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3974–4001. doi:10.1002/anie.200460842

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, W.; Yang, X. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 692–710. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100091

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Tang, M.; Liu, H.; Yang, X. Sci. China: Chem. 2024, 67, 973–980. doi:10.1007/s11426-023-1810-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xie, J.; Guo, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D.; He, Y.-P.; Yang, X. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 1674–1680. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202200125

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Y.; Zhu, C.; Guo, Z.; Liu, W.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 5268–5272. doi:10.1002/anie.202015008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, W.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 23598–23602. doi:10.1002/anie.202009395

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chu, A.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr1628. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adr1628

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, W.-M.; Hao, Y.-J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.-G.; Ji, S.-J.; Cai, Z.-J. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 363–368. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.4c04350

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hassan, Z.; Spuling, E.; Knoll, D. M.; Lahann, J.; Bräse, S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 6947–6963. doi:10.1039/c7cs00803a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhu, K.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, F. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 110678. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2024.110678

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Y.-H.; Zhu, D.; Chen, Z.-M. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202401312. doi:10.1002/cctc.202401312

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, G.; Wang, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202412805. doi:10.1002/anie.202412805

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400841. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202400841

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Lai, Y.; Yang, X. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100413. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2021.100413

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pan, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, W.; Yang, X. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 8443–8448. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c02331

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, S.; Shen, G.; He, F.; Yang, X. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7293–7296. doi:10.1039/d2cc01690g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, J.; Zhao, C. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 14155–14162. doi:10.1021/acscatal.3c03718

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.-X.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, H.; Li, X. Chin. J. Chem. 2025, 43, 1263–1270. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202500010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, H.-H.; Jiang, J.-T.; Yang, Y.-N.; Ye, L.-W.; Zhou, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202505167. doi:10.1002/anie.202505167

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, S.; Bao, H.; Zhang, D.; Yang, X. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5239. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40718-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Böhmer, V.; Kraft, D.; Tabatabai, M. J. Inclusion Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem. 1994, 19, 17–39. doi:10.1007/bf00708972

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Han, J.-W.; Chen, J.-X.; Li, X.; Peng, X.-S.; Wong, H. N. C. Synlett 2013, 24, 2188–2198. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1339859

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, Y.; Wu, G.; Yang, Z.; Rouh, H.; Katakam, N.; Ahmed, S.; Unruh, D.; Cui, Z.; Lischka, H.; Li, G. Sci. China: Chem. 2020, 63, 692–698. doi:10.1007/s11426-019-9711-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 5307–5322. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5c00479

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tang, M.; Yang, X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300738. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202300738

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, S.; Yuan, M.; Xie, W.; Ye, Z.; Qin, T.; Yu, N.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202410628. doi:10.1002/anie.202410628

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, Y.-K.; Tian, Y.-L.; Feng, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, W.-A.; Xu, X.-D.; Liu, R.-R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407752. doi:10.1002/anie.202407752

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ye, Z.; Xie, W.; Liu, W.; Zhou, C.; Yang, X. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403125. doi:10.1002/advs.202403125

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yuan, M.; Xie, W.; Yu, S.; Liu, T.; Yang, X. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3943. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-59221-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, X.-C.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.-D.; Tong, S.; Wang, M.-X. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3610–3615. doi:10.1039/d3sc06436k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, D.; Zhou, J.; Qin, T.; Yang, X. Chem Catal. 2024, 4, 100827. doi:10.1016/j.checat.2023.100827

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, J.; Tang, M.; Yang, X. Chin. J. Chem. 2024, 42, 1953–1959. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202400243

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nimmagadda, S. K.; Mallojjala, S. C.; Woztas, L.; Wheeler, S. E.; Antilla, J. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 2454–2458. doi:10.1002/anie.201611602

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, J.-H.; Li, X.-K.; Feng, J.; Yao, W.; Zhang, H.; Lu, C.-J.; Liu, R.-R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319289. doi:10.1002/anie.202319289

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 37. | Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Lai, Y.; Yang, X. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100413. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2021.100413 |

| 38. | Pan, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, W.; Yang, X. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 8443–8448. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c02331 |

| 39. | Yu, S.; Shen, G.; He, F.; Yang, X. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7293–7296. doi:10.1039/d2cc01690g |

| 40. | Li, J.; Zhao, C. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 14155–14162. doi:10.1021/acscatal.3c03718 |

| 1. | Akiyama, T.; Itoh, J.; Yokota, K.; Fuchibe, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1566–1568. doi:10.1002/anie.200353240 |

| 10. | Mori, K.; Ichikawa, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Shibata, Y.; Yamanaka, M.; Akiyama, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3964–3970. doi:10.1021/ja311902f |

| 13. | Liu, W.; Qin, T.; Xie, W.; Zhou, J.; Ye, Z.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303430. doi:10.1002/anie.202303430 |

| 47. | Luo, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 5307–5322. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5c00479 |

| 48. | Tang, M.; Yang, X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300738. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202300738 |

| 9. | Cheng, J. K.; Xiang, S.-H.; Li, S.; Ye, L.; Tan, B. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4805–4902. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01306 |

| 14. | Li, C.; Shao, Y.-B.; Gao, X.; Ren, Z.; Guo, C.; Li, M.; Li, X. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3380. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39134-9 |

| 49. | Yu, S.; Yuan, M.; Xie, W.; Ye, Z.; Qin, T.; Yu, N.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202410628. doi:10.1002/anie.202410628 |

| 3. | Akiyama, T. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5744–5758. doi:10.1021/cr068374j |

| 4. | Terada, M. Synthesis 2010, 1929–1982. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1218801 |

| 5. | Parmar, D.; Sugiono, E.; Raja, S.; Rueping, M. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9047–9153. doi:10.1021/cr5001496 |

| 6. | Akiyama, T.; Mori, K. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9277–9306. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00041 |

| 7. | Rahman, A.; Lin, X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 4753–4777. doi:10.1039/c8ob00900g |

| 8. | Li, X.; Song, Q. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018, 29, 1181–1192. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.01.045 |

| 20. | Huang, Q.; Tang, Y.-P.; Zhang, C.-G.; Wang, Z.; Dai, L. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 16256–16265. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c05345 |

| 45. | Han, J.-W.; Chen, J.-X.; Li, X.; Peng, X.-S.; Wong, H. N. C. Synlett 2013, 24, 2188–2198. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1339859 |

| 2. | Uraguchi, D.; Terada, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5356–5357. doi:10.1021/ja0491533 |

| 12. | Kötzner, L.; Webber, M. J.; Martínez, A.; De Fusco, C.; List, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5202–5205. doi:10.1002/anie.201400474 |

| 46. | Liu, Y.; Wu, G.; Yang, Z.; Rouh, H.; Katakam, N.; Ahmed, S.; Unruh, D.; Cui, Z.; Lischka, H.; Li, G. Sci. China: Chem. 2020, 63, 692–698. doi:10.1007/s11426-019-9711-x |

| 15. | Wang, D.; Shao, Y.-B.; Chen, Y.; Xue, X.-S.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202201064. doi:10.1002/anie.202201064 |

| 43. | Yu, S.; Bao, H.; Zhang, D.; Yang, X. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5239. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40718-8 |

| 13. | Liu, W.; Qin, T.; Xie, W.; Zhou, J.; Ye, Z.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303430. doi:10.1002/anie.202303430 |

| 14. | Li, C.; Shao, Y.-B.; Gao, X.; Ren, Z.; Guo, C.; Li, M.; Li, X. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3380. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39134-9 |

| 18. | Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.-G.; Shi, F. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 3077–3111. doi:10.1016/j.checat.2022.10.011 |

| 19. | Liu, W.; Qin, T.; Xie, W.; Yang, X. Chem. – Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202202369. doi:10.1002/chem.202202369 |

| 44. | Böhmer, V.; Kraft, D.; Tabatabai, M. J. Inclusion Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem. 1994, 19, 17–39. doi:10.1007/bf00708972 |

| 12. | Kötzner, L.; Webber, M. J.; Martínez, A.; De Fusco, C.; List, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5202–5205. doi:10.1002/anie.201400474 |

| 41. | Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.-X.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, H.; Li, X. Chin. J. Chem. 2025, 43, 1263–1270. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202500010 |

| 11. | Da, B.-C.; Xiang, S.-H.; Li, S.; Tan, B. Chin. J. Chem. 2021, 39, 1787–1796. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202000751 |

| 16. | Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Peng, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, T.; Cheng, S.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Gan, C.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 982–993. doi:10.31635/ccschem.022.202201901 |

| 42. | Chen, H.-H.; Jiang, J.-T.; Yang, Y.-N.; Ye, L.-W.; Zhou, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202505167. doi:10.1002/anie.202505167 |

| 23. | Xu, W.-L.; Zhang, R.-X.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202318021. doi:10.1002/anie.202318021 |

| 21. | Xie, W.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Qin, T.; Yang, X. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 101993. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2024.101993 |

| 50. | Jiang, Y.-K.; Tian, Y.-L.; Feng, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, W.-A.; Xu, X.-D.; Liu, R.-R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407752. doi:10.1002/anie.202407752 |

| 22. | Qin, T.; Xie, W.; Liu, W.; Yang, X. Org. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 1417–1424. doi:10.1039/d4qo02188f |

| 51. | Ye, Z.; Xie, W.; Liu, W.; Zhou, C.; Yang, X. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403125. doi:10.1002/advs.202403125 |

| 52. | Yuan, M.; Xie, W.; Yu, S.; Liu, T.; Yang, X. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3943. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-59221-3 |

| 33. | Zhu, K.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, F. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 110678. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2024.110678 |

| 34. | Zhao, Y.-H.; Zhu, D.; Chen, Z.-M. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202401312. doi:10.1002/cctc.202401312 |

| 35. | Yang, G.; Wang, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202412805. doi:10.1002/anie.202412805 |

| 36. | Dong, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400841. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202400841 |

| 15. | Wang, D.; Shao, Y.-B.; Chen, Y.; Xue, X.-S.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202201064. doi:10.1002/anie.202201064 |

| 31. | Liu, W.-M.; Hao, Y.-J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.-G.; Ji, S.-J.; Cai, Z.-J. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 363–368. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.4c04350 |

| 56. | Nimmagadda, S. K.; Mallojjala, S. C.; Woztas, L.; Wheeler, S. E.; Antilla, J. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 2454–2458. doi:10.1002/anie.201611602 |

| 32. | Hassan, Z.; Spuling, E.; Knoll, D. M.; Lahann, J.; Bräse, S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 6947–6963. doi:10.1039/c7cs00803a |

| 57. | Li, J.-H.; Li, X.-K.; Feng, J.; Yao, W.; Zhang, H.; Lu, C.-J.; Liu, R.-R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319289. doi:10.1002/anie.202319289 |

| 29. | Liu, W.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 23598–23602. doi:10.1002/anie.202009395 |

| 54. | Zhang, D.; Zhou, J.; Qin, T.; Yang, X. Chem Catal. 2024, 4, 100827. doi:10.1016/j.checat.2023.100827 |

| 30. | Chu, A.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr1628. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adr1628 |

| 55. | Zhou, J.; Tang, M.; Yang, X. Chin. J. Chem. 2024, 42, 1953–1959. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202400243 |

| 24. | Vedejs, E.; Jure, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3974–4001. doi:10.1002/anie.200460842 |

| 25. | Liu, W.; Yang, X. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 692–710. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100091 |

| 53. | Li, X.-C.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.-D.; Tong, S.; Wang, M.-X. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3610–3615. doi:10.1039/d3sc06436k |

| 26. | Jiang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Tang, M.; Liu, H.; Yang, X. Sci. China: Chem. 2024, 67, 973–980. doi:10.1007/s11426-023-1810-9 |

| 27. | Xie, J.; Guo, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D.; He, Y.-P.; Yang, X. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 1674–1680. doi:10.1002/cjoc.202200125 |

| 28. | Chen, Y.; Zhu, C.; Guo, Z.; Liu, W.; Yang, X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 5268–5272. doi:10.1002/anie.202015008 |

| 16. | Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Peng, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, T.; Cheng, S.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Gan, C.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 982–993. doi:10.31635/ccschem.022.202201901 |

© 2025 Liu and Yang; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.