Abstract

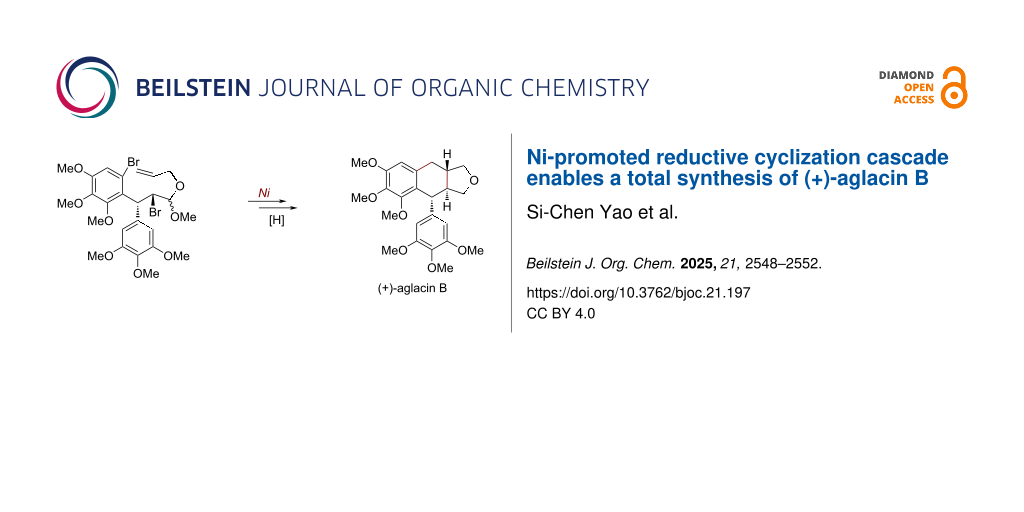

The total synthesis of bioactive (+)-aglacin B was achieved. The key steps include an asymmetric conjugate addition reaction induced by a chiral auxiliary and a nickel-promoted reductive tandem cyclization of the elaborated β-bromo acetal, which led to the efficient construction of the aryltetralin[2,3-c]furan skeleton embedded in this natural product.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Proksch and co-workers isolated aglacins A, B, C, and E (1–4, Figure 1) from the methanolic extract of stem bark of Aglaia cordata Hiern from the tropical rain forests of the Kalimantan region (Indonesia) [1,2]. These cyclic ether natural products belong to the typical aryltetralin lignans, which have already attracted broad attention from the synthetic community [3-5]. Zhu and co-workers disclosed a concise synthesis of (±)-aglacins B (2) and C (3), featuring a visible light-catalyzed radical cation cascade for the formation of the C8–C8′ and C2–C7′ bonds [6]. Subsequently, they improved the reaction conditions to achieve the racemic synthesis of aglacins A (1) and E (4) as well [7]. In 2021, the Gao group described the total synthesis of both enantiomers of aglacins A (1), B (2), and E (4) by asymmetric photoenolization/Diels–Alder reactions as the key steps for the construction of the C7–C8 and C7′–C8′ bonds [8].

Figure 1: The structures of aglacins A, B, C, and E.

Figure 1: The structures of aglacins A, B, C, and E.

During the past decade, we had developed nickel-catalyzed or -promoted reductive coupling/cyclization reactions for the formation of inter- or intramolecular carbon–carbon bonds under mild conditions [9-12], and strategically applied this method for the divergent syntheses of some natural products [13-17]. Herein, we report our recent advance to a total synthesis of (+)-aglacin B (2), which relies on a non-photocatalysis approach.

Results and Discussion

Retrosynthetic analysis of (+)-aglacin B

Based on the retrosynthetic analysis shown in Scheme 1, both C8′–C8 and C7–C1 bonds in (+)-aglacin B (2) could be constructed in one-step from the β-bromo acetal 5 by a Ni-promoted tandem radical cyclization, and a subsequent acetal reduction under acidic conditions then can complete the total synthesis of this molecule. The cyclization precursor 5 could be prepared from the primary alcohol 6 through transforming functional groups of the alkyl chain and installing an allyl group. It was envisioned that the diarylmethine stereocenter at C7′ in 6 could be formed by an Evans’ auxiliary-induced asymmetric conjugate addition of α,β-unsaturated acyl oxazolidinone 7 with 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylmagnesium bromide (8). Both of these two building blocks could be conveniently prepared from commercially available 2,6-dimethoxyphenol [18,19].

Scheme 1: Retrosynthetic analysis of (+)-aglacin B (2).

Scheme 1: Retrosynthetic analysis of (+)-aglacin B (2).

Synthesis of cyclization precursor 5 and (+)-aglacin B

As shown in Scheme 2, the forward synthesis began with a triethyl phosphonoacetate-mediated Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons (HWE) reaction of o-bromobenzaldehyde 9 derived from 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (Supporting Information File 1). The generated ester 10 was then converted into the corresponding acyl chloride by saponification and subsequent reaction with pivaloyl chloride. The resulting acyl chloride was then trapped by (S)-4-phenyl-2-oxazolidinone (11) to produce the desired α,β-unsaturated amide 7. Next, the asymmetric conjugate addition was carried out [20,21]. The in situ generated aryl–copper(I) species was obtained under the action of CuBr·Me2S with Grignard reagent 8, and then added to a THF solution of the α,β-unsaturated acyl oxazolidinone 7 at −48 °C. This reaction demonstrated an excellent diastereocontrol for 12 (dr = 20:1), and could easily proceed on a scale of ten grams (Supporting Information File 1). For the reduction of the chiral auxiliary in 12, NaBH4 in THF/H2O proved to be the optimal conditions, giving the primary alcohol 6 in 80% yield. Subsequently, oxidation of this alcohol by IBX followed by reaction with CH(OMe)3 afforded acetal 17, which was then subjected to a CH2Cl2 solution of TMSOTf and iPr2NEt. A mixture of enol methyl ethers 18 were thus produced by an elimination reaction. Eventually, a site-selective bromination of the double bond over the electron-rich benzene rings with 2,4,4,6-tetrabromo-2,5-cyclohexadienone (TBCD) in CH2Cl2 followed by reaction with allyl alcohol, provided β-bromo acetal 5 in 30% overall yield starting from alcohol 6.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of cyclization precursor 5.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of cyclization precursor 5.

With a successful preparation of the cyclization precursor 5, the designed nickel-promoted reductive tandem cyclization was pursued (Scheme 3). By slightly modifying the reaction conditions of our previous studies [11,12], the expected bicyclization of 5 occurred smoothly, resulting in an efficient construction of the trans-tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-c]furan skeleton embedded in 13, which could be separated from the other diastereomer [14] by flash column chromatography in 30% yield. The stereocontrolled formation of aryltetralin 13 could be attributed to an adoption of a pseudo-half-chair conformation 5a. Finally, the final step towards the total synthesis of (+)-aglacin B (2) was achieved by treatment with BF3·Et2O as the Lewis acid and Et3SiH as the hydrogen source [22], affording this natural product in 58% isolated yield. NMR data of the synthetic sample were found to be in agreement with those of previous literature (Tables S1 and S2, Supporting Information File 1). Moreover, the newly synthesized (+)-aglacin B (2) formed single crystals, and a corresponding X-ray diffraction analysis (inset in Scheme 3, selected H atoms have been omitted for clarity, and Table S3, Supporting Information File 1) unambiguously confirmed its precise structure with three continuous chiral centers.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of (+)-aglacin B (2).

Scheme 3: Synthesis of (+)-aglacin B (2).

Conclusion

In summary, the total synthesis of (+)-aglacin B, a typical aryltetralin natural product [23,24], was completed from 2,6-dimethoxyphenol. The key Ni-promoted reductive cyclization cascade of a β-bromo acetal with an allyl tether, smoothly established the tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-c]furan core of this molecule in a new fashion.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, characterization data, and copies of 1H/13C NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.8 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Wang, B.-G.; Ebel, R.; Nugroho, B. W.; Prijono, D.; Frank, W.; Steube, K. G.; Hao, X.-J.; Proksch, P. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1521–1526. doi:10.1021/np0102962

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, B.-G.; Ebel, R.; Wang, C.-Y.; Wray, V.; Proksch, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 5783–5787. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(02)01180-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yao, S.-C.; Xiao, J.; Nan, G.-M.; Peng, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2023, 115, 154309. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.154309

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, H.-Q.; Yan, C.-X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 1623–1636. doi:10.1039/d1ob02457d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reynolds, R. G.; Nguyen, H. Q. A.; Reddel, J. C. T.; Thomson, R. J. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 670–702. doi:10.1039/d1np00057h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiang, J.-C.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21195–21202. doi:10.1002/anie.202007548

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiang, J.-C.; Fung, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3481. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31000-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, M.; Hou, M.; He, H.; Gao, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 16655–16660. doi:10.1002/anie.202105395

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yan, C.-S.; Peng, Y.; Xu, X.-B.; Wang, Y.-W. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6039–6048. doi:10.1002/chem.201200190

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, Y.; Xu, X.-B.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.-W. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 472–474. doi:10.1039/c3cc47780k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xu, X.-B.; Duan, S.-M.; Ren, L.; Shao, Y.-L.; Wang, Y.-W. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5170–5173. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02665

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Xiao, J.; Cong, X.-W.; Yang, G.-Z.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2040–2043. doi:10.1039/c8cc00001h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Peng, Y.; Luo, L.; Yan, C.-S.; Zhang, J.-J.; Wang, Y.-W. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10960–10967. doi:10.1021/jo401936v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiao, J.; Cong, X.-W.; Yang, G.-Z.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1651–1654. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00408

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Luo, L.; Zhai, X.-Y.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y.; Gong, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 989–992. doi:10.1002/chem.201805682

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cao, J.-S.; Zeng, J.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X.-H.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7273–7276. doi:10.1039/d2cc02221d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, Z.-H.; Xiao, J.; Zhai, Q.-Q.; Tang, X.; Xu, L.-J.; Zhuang, Z.-Y.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 694–697. doi:10.1039/d3cc05312a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Percec, V.; Holerca, M. N.; Nummelin, S.; Morrison, J. J.; Glodde, M.; Smidrkal, J.; Peterca, M.; Rosen, B. M.; Uchida, S.; Balagurusamy, V. S. K.; Sienkowska, M. J.; Heiney, P. A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2006, 12, 6216–6241. doi:10.1002/chem.200600178

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Massé, P.; Choppin, S.; Chiummiento, L.; Colobert, F.; Hanquet, G. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 3033–3040. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c02489

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Andrews, R. C.; Teague, S. J.; Meyers, A. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 7854–7858. doi:10.1021/ja00231a041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, C.-y.; Reamer, R. A. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 293–294. doi:10.1021/ol990608g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mason, J. D.; Terwilliger, D. W.; Pote, A. R.; Myers, A. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 11019–11025. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c03529

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Y.; Yun, Z.; Quynh Nguyen, T.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y. CCS Chem. 2025, in press. doi:10.31635/ccschem.025.202505994

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, W.-X.; Peng, Z.; Gu, Q.-X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, L.-H.; Leng, F.; Lu, H.-H. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3, 986–997. doi:10.1038/s44160-024-00564-y

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Wang, B.-G.; Ebel, R.; Nugroho, B. W.; Prijono, D.; Frank, W.; Steube, K. G.; Hao, X.-J.; Proksch, P. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1521–1526. doi:10.1021/np0102962 |

| 2. | Wang, B.-G.; Ebel, R.; Wang, C.-Y.; Wray, V.; Proksch, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 5783–5787. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(02)01180-2 |

| 8. | Xu, M.; Hou, M.; He, H.; Gao, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 16655–16660. doi:10.1002/anie.202105395 |

| 7. | Xiang, J.-C.; Fung, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3481. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31000-4 |

| 6. | Xiang, J.-C.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21195–21202. doi:10.1002/anie.202007548 |

| 23. | Chen, Y.; Yun, Z.; Quynh Nguyen, T.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y. CCS Chem. 2025, in press. doi:10.31635/ccschem.025.202505994 |

| 24. | Xu, W.-X.; Peng, Z.; Gu, Q.-X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, L.-H.; Leng, F.; Lu, H.-H. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3, 986–997. doi:10.1038/s44160-024-00564-y |

| 3. | Yao, S.-C.; Xiao, J.; Nan, G.-M.; Peng, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2023, 115, 154309. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.154309 |

| 4. | Zhang, H.-Q.; Yan, C.-X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 1623–1636. doi:10.1039/d1ob02457d |

| 5. | Reynolds, R. G.; Nguyen, H. Q. A.; Reddel, J. C. T.; Thomson, R. J. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 670–702. doi:10.1039/d1np00057h |

| 20. | Andrews, R. C.; Teague, S. J.; Meyers, A. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 7854–7858. doi:10.1021/ja00231a041 |

| 21. | Chen, C.-y.; Reamer, R. A. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 293–294. doi:10.1021/ol990608g |

| 14. | Xiao, J.; Cong, X.-W.; Yang, G.-Z.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1651–1654. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00408 |

| 18. | Percec, V.; Holerca, M. N.; Nummelin, S.; Morrison, J. J.; Glodde, M.; Smidrkal, J.; Peterca, M.; Rosen, B. M.; Uchida, S.; Balagurusamy, V. S. K.; Sienkowska, M. J.; Heiney, P. A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2006, 12, 6216–6241. doi:10.1002/chem.200600178 |

| 19. | Massé, P.; Choppin, S.; Chiummiento, L.; Colobert, F.; Hanquet, G. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 3033–3040. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c02489 |

| 22. | Mason, J. D.; Terwilliger, D. W.; Pote, A. R.; Myers, A. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 11019–11025. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c03529 |

| 13. | Peng, Y.; Luo, L.; Yan, C.-S.; Zhang, J.-J.; Wang, Y.-W. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10960–10967. doi:10.1021/jo401936v |

| 14. | Xiao, J.; Cong, X.-W.; Yang, G.-Z.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1651–1654. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00408 |

| 15. | Luo, L.; Zhai, X.-Y.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y.; Gong, H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 989–992. doi:10.1002/chem.201805682 |

| 16. | Cao, J.-S.; Zeng, J.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X.-H.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7273–7276. doi:10.1039/d2cc02221d |

| 17. | Liu, Z.-H.; Xiao, J.; Zhai, Q.-Q.; Tang, X.; Xu, L.-J.; Zhuang, Z.-Y.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 694–697. doi:10.1039/d3cc05312a |

| 9. | Yan, C.-S.; Peng, Y.; Xu, X.-B.; Wang, Y.-W. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6039–6048. doi:10.1002/chem.201200190 |

| 10. | Peng, Y.; Xu, X.-B.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.-W. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 472–474. doi:10.1039/c3cc47780k |

| 11. | Peng, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xu, X.-B.; Duan, S.-M.; Ren, L.; Shao, Y.-L.; Wang, Y.-W. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5170–5173. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02665 |

| 12. | Xiao, J.; Cong, X.-W.; Yang, G.-Z.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2040–2043. doi:10.1039/c8cc00001h |

| 11. | Peng, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xu, X.-B.; Duan, S.-M.; Ren, L.; Shao, Y.-L.; Wang, Y.-W. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5170–5173. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02665 |

| 12. | Xiao, J.; Cong, X.-W.; Yang, G.-Z.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2040–2043. doi:10.1039/c8cc00001h |

© 2025 Yao et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.