Abstract

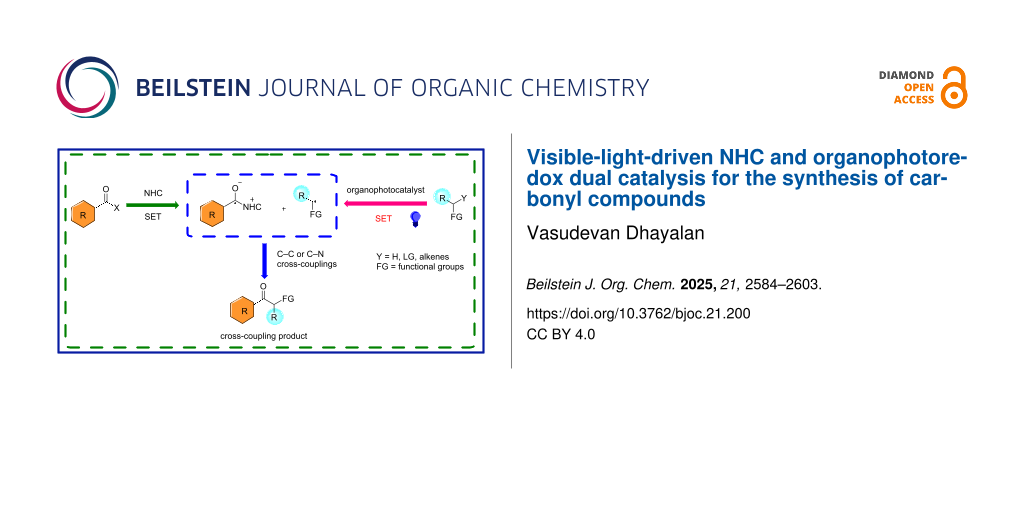

Over the past two decades, organocatalyzed visible-light-mediated radical chemistry has significantly influenced modern synthetic organic chemistry. In particular, dual catalysis combining N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) with organophotocatalysts (e.g., 4CzIPN, eosin Y, rhodamine, 3DPAFIPN, Mes-Acr-Me+ClO4−) has emerged as a powerful photocatalytic strategy for efficiently constructing a wide variety of carbonyl compounds via radical cross-coupling processes. This cooperative organic dual catalysis has great potential in medicinal, pharmaceutical, and materials science applications, including the development of organic semiconductors and polymers. In recent years, NHC-involved photocatalysis has attracted considerable attention in synthetic organic chemistry, and particularly in the late-stage functionalization of bioactive compounds, drugs, and natural products. This review highlights recent advances in NHC–organophotoredox dual catalysis, focusing on methodology development, mechanistic insights, and reaction scope for synthesizing carbonyl compounds and pharmaceutically relevant intermediates. Moreover, this catalytic system operates under green and sustainable conditions, tolerating a broad range of functional groups and substrate scope, and utilizes low-cost, atom-economical, non-toxic starting materials.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Over the last ten years, NHC-catalyzed visible-light-promoted radical chemistry has been extensively developed for the cost-effective and practical synthesis of bioactive intermediates, pharmaceuticals, drugs, and natural products [1-6]. Recently developed photocatalysis affords sustainable, regioselective green methods for producing a wide range of functionalized carbonyl compounds and their related bioactive chiral intermediates under mild conditions, employing dual organic photoredox catalysis [7-11]. The use of visible light as an energy source has significantly expanded the scope of organic molecule activation and its application in organic synthesis or medicinal chemistry [12], thereby driving the fast development of various photocatalytic transformations. Among these advances, dual catalysis, particularly the synergistic combination of N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) with organic photocatalysts, has opened new avenues in molecular construction, particularly for the novel, practical preparation of carbonyl group-containing compounds [13-16]. These ubiquitous ketone, ester, and amide functional groups are found in various drugs, natural products, and optoelectronic materials.

In the last three decades, N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) have been renowned as versatile organocatalysts, including thiazolium, imidazolium, and triazolium moieties. NHCs are extensively used in many catalytic asymmetric reactions and are functional transformations in synthetic organic chemistry. Especially, 1,2,3-triazole-based NHCs are generally more reactive and stronger σ-donors than imidazole or thiazole analogues. Triazolium NHC enhances their ability to stabilize reactive radical intermediates or acyl anion equivalents, which is crucial in dual or triple catalytic cycles. The electron-rich carbene center facilitates faster SET processes in photocatalytic reactions. Triazolium-based NHCs exhibit higher oxidative and photochemical stability, making them well-suited for visible-light-driven catalytic transformations. Previous reports displayed various research groups successfully designed and prepared a variety of triazolium-based NHCs, eventually leading to the development of chiral NHC scaffolds by Knight and Leeper [17], followed by the remarkable contributions of Bode [18], Rovis [19], Glorius [20], Enders [21], Rafinski [22], Scheidt [23], Connon [24], Chi [25], Milo [26,27], Gravel [28,29] and others [30]. These NHC-catalyzed developments have drastically improved the achievable diastereo- and enantioselectivity, including common named reactions such as benzoin reactions, Stetter reactions, Michael additions, cycloadditions, domino reactions, cascade annulations, Diels–Alder reactions, and Michael–Stetter reactions, to name a few [31-35].

Notably, previous reports have demonstrated that the utility of chiral N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysts permits contracting asymmetric C–C, C–HA bond-forming reactions [36,37]. These chiral NHC catalysts, used to access enantiopure alcohol/amine derivatives, particularly 2° and 3° alcohols/amines, are significant structural motifs in numerous drugs and natural products and have found widespread synthetic applications in medicinal chemistry and active pharmaceutical ingredients [38-40].

Over the years, the groups of Hopkinson, Wang, Dong, Marzo, and co-workers published a comprehensive review detailing the synthetic approaches and mechanistic insights of visible light-promoted dual photocatalysis that combined N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) with photocatalysts. The review encompasses transition-metal-based photocatalytic reactions for C–C and C–HA cross-coupling reactions involving various acyl fluorides, amides, aldehydes, carboxylic acids, and esters, highlighting their broad applications in organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry. However, to my knowledge, a review paper on visible-light-promoted dual organocatalyzed photochemical reactions has not been reported. Therefore, this work is helpful for readers to gain a comprehensive understanding of NHC-based dual organocatalyzed photochemical reactions [13-16]. The groups of MacMillan, Studer, Chi, Plunkett, Rovis, Hopkinson, and others developed NHC-involved radical reactions via visible light-promoted dual or triple photocatalysis, including NHC and transition metal-based photocatalytic reactions and their application in organic synthesis [41-50].

This review focuses on recent synthetic developments of NHC-catalyzed, visible-light-promoted dual organophotocatalysis for preparing carbonyl compounds and related organic intermediates by combining NHC and organic photocatalysts. Organocatalysts have a significant impact on the process, such as being environmentally friendly, offering operational simplicity, lower cost, and easy availability, reducing waste and toxicity, as well as providing excellent chemo-, regio-, and enantioselectivity through fine-tuned hydrogen bonding or covalent activation modes. Furthermore, the continued integration of this versatile photocatalytic platform with sustainable methods such as visible-light harvesting and the use of earth-abundant catalysts is expected to further enhance its impact across diverse research fields, including chemical biology, pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, polymers, and advanced optical and energy materials.

Review

Visible-light-driven NHC/4CzIPN-catalyzed reactions

Recently, Shu and co-workers developed a direct and innovative preparation of highly functionalized aryl amide derivatives 3 from aryl aldehydes 1 and substituted imines 2 under mild conditions in the presence of NHC (10 mol %) and 4CzIPN (2 mol %) and Na2HPO4 in DMSO at rt for 10–24 h. The key to success lies in the photocatalytic dual system, which combines two organocatalysts (NHC/4CzIPN) and visible light irradiation to permit a novel umpolung single-electron reduction of respective imino ester 2, generating an N-centered radical species C. This species subsequently undergoes a rapid C–N cross-coupling with ketyl radical B. This cross-coupling method offers a transition-metal free route to highly substituted amides 3 from aldehydes 1 and imines 2, without the need for any external reductants or oxidants, and proceeds in an atom-economical manner. This photochemical reaction displays a wide substrate scope, tolerating a broad range of aryl and aliphatic aldehydes with good functional group compatibility. Mechanistic studies revealed that the photochemical reaction proceeds via radical–radical cross-coupling between the C-centered and N-centered radicals. These methods are expected to open new avenues for visible-light- and NHC/4CzIPN-catalyzed carbon–heteroatom bond-forming processes (Scheme 1) [51].

Scheme 1: NHC-catalyzed umpolung strategy for the metal-free synthesis of amide via dual catalysis.

Scheme 1: NHC-catalyzed umpolung strategy for the metal-free synthesis of amide via dual catalysis.

In 2021, Studer et al. developed a novel method for the 1,3-difunctionalization of arylcyclopropanes 5 by applying NHC/ photoredox cooperative organocatalysis under visible-light irradiation. This method allows sequential C–O and C–C bond formation, leading to access to various γ-aroyloxy keto-ester derivatives 6 in good yield up to 81% and excellent functional group tolerance, including electron-rich and electron-poor substituents. This reaction was carried out between arylcyclopropanes 5 and acyl fluoride 4 in the presence of NHC (10 mol %) and 4CzIPN (5 mol %). Mechanistic studies showed that the cascade proceeds via nucleophilic ring-opening of a cyclopropyl radical cation D with subsequent radical-/radical cross-coupling performed between intermediates C and E. The reaction of acyl fluoride 4 in the presence of Cs2CO3 and NHC to produce benzoate A and the formation of some reactive intermediates are shown in Scheme 2. These methods will find suitable application in medicinal chemistry and related biological branches (Scheme 2) [52].

Scheme 2: Visible-light promoted cooperative NHC/photoredox catalyzed ring-opening of aryl cyclopropanes.

Scheme 2: Visible-light promoted cooperative NHC/photoredox catalyzed ring-opening of aryl cyclopropanes.

Studer and his group efficiently developed a method to achieve the acylation of benzylic C(sp³)–H bonds via cooperative NHC and organophotocatalyzed dual catalysis. The key step in the reaction is a radical–radical cross-coupling process leading to the production of ketone scaffolds, including drug moieties. The organocatalyzed acylation proceeds with excellent site selectivity and broad functional group tolerance of alkanes such as F, Cl, Br, I, CN, CF3, Me, and OMe. The reaction was achieved between acyl fluoride 4 and highly substituted alkane 7 in the presence of NHC (20 mol %), 4CzIPN (2 mol %) under mild conditions, producing corresponding unsymmetrical ketone derivatives 8 in up to 95% yield. An Ir-based photocatalyst was initially selected because its excited state is a strong oxidant (E1/2[Ir*III/II] = +1.21 V). Although 4-ethylanisole exhibits a higher oxidation potential (E1/2 = +1.52 V). This reaction was examined using different solvents, and it was found that toluene and 1,4-dioxane gave low yields (4–5% yield). Under blue LED irradiation, Ir-based PC is photoexcited, and its excited state is reductively quenched by the electron-rich arene substrate 7, generating the aryl radical cation C along with the formation of corresponding radical anion of the photocatalyst (PC•–). The reduction potentials are (E1/2(P/P•–) = –1.37V vs SCE for [Ir(dF(CF₃)ppy)₂(dtbbpy)]PF₆ and –1.21V vs SCE for 4CzIPN as an organophotocatalyst. This method permits the C–H bond functionalization of important structural motifs with good to excellent diastereoselectivities, high yields, and late-stage functionalization of drugs and complex natural products. The visible-light-promoted dual catalytic method opens new avenues in direct C–H bond acylation and complements existing metal-catalyzed C–H bond functionalization methods (Scheme 3) [53].

Scheme 3: NHC-catalyzed benzylic C–H acylation by dual catalysis.

Scheme 3: NHC-catalyzed benzylic C–H acylation by dual catalysis.

Recently, Scheidt et al. discovered an NHC/organic photoredox-catalyzed three-component coupling reaction for the efficient and novel preparation of γ-aryloxy ketone scaffolds 12. This transformation builds on the emerging field of single-electron NHC catalysis by incorporating oxidatively generated aryloxymethyl radicals A as a key intermediate. A variety of γ-aryloxy ketones 12 were successfully prepared in the presence of NHC (15 mol %), photocatalyst (2 mol %), using 467 nm LED and a combination of alkene 11, amide 9, and aryloxymethyl potassium trifluoroborate salt 10 under mild conditions. The described catalytic system exhibited broad functional group tolerance and efficiently employed terminal alkenes 11 to generate quaternary centers adjacent to the carbonyl group. The key step in this organocatalytic process is the reduction of acylazolium C to generate a stable benzylic radical D is formed, and this extends the lifetime of the radical, allowing for radical–radical coupling reaction to afford the desired γ-aryloxy ketones 12 in good yields. The utility of this sustainable method was further demonstrated by the removal of the PMP protecting group using 2 equivalents of CAN and pyridine, affording 2,3-dihydrofurans 12a in 58% (Scheme 4) [54].

Scheme 4: NHC/photoredox-catalyzed three-component coupling reaction for the preparation of γ-aryloxy ketones.

Scheme 4: NHC/photoredox-catalyzed three-component coupling reaction for the preparation of γ-aryloxy ketones....

In 2022, Sumida, Ohmiya, and co-workers developed a dual NHC/4CzIPN-organocatalyzed, versatile, light-driven silyl radical generation strategy from substituted silylboronates 13. This photochemical method operates via catalytic activation of the silylboronate 13 in the presence of NHC (10 mol %) and 4CZIPN (1 mol %) with Rb2CO3 (10 mol %) as a base in CH3CN at rt for 20 h. The approach affords highly functionalized β-silylated aryl ketones 14 in moderate to good yields, tolerates a variety of functional groups, and offers a wide substrate scope. Under the optimized conditions, Rb2CO3 provided better results than DMAP and Cs2CO3. The acyl azolium complex B was synthesized from acyl imidazole 9 using an NHC and Rb2CO3 as the base. Considering the redox potential of 4CzIPN and the acylazolium complex B (Ep = −0.81 V vs SCE), single-electron transfer (SET) reduction of B was thermodynamically feasible; however, the efficiency was found to be significantly low. The oxidation potential was measured to be around [Ep = +0.72 V] vs SCE, indicating that it is sufficiently positive to enable SET oxidation by photoexcited 4CzIPN. The authors described that the reduction potential of the photoredox catalyst (PC = 4CzIPN) was moderately low [Ered(IrIII*/IrII) = +0.66 V vs SCE in MeCN], and the silylboronate 13 permitted the formation of the silyl radical C under mild oxidation conditions. This visible-light-mediated dual catalytic method permits the efficient acylsilylation of substituted terminal alkenes 11 via NHC catalysis. Remarkably, this method afforded silyl radicals, which are typically difficult to prepare using conventional HAT-based catalytic methods. This method is used for late-stage modification of bioactive compounds, including natural products. These developments will find suitable applications in medicinal chemistry for introducible organosilyl groups (Scheme 5) [55].

Scheme 5: NHC-catalyzed silyl radical generation from silylboronate via dual catalysis.

Scheme 5: NHC-catalyzed silyl radical generation from silylboronate via dual catalysis.

A visible-light-induced Friedel–Crafts acylation of arenes and heteroarenes was reported by Studer et al., which belongs to the class of aryl and heteroaryl electrophilic substitutions and is a highly versatile synthetic transformation in traditional organic chemistry. A highly regioselective dual catalytic approach for the novel acylation of electron-rich benzo-fused arenes or heterocycles 15 was described. Aromatic C(sp2)–H bond acylation was achieved by dual catalysis through cooperative NHC and organophotoredox-catalyzed C–C cross-coupling of a benzo-fused aryl radical cation C with stable ketyl radical B as the key step. LED irradiation of photocatalyst leads to photoexcited PC*, which is reductively quenched by arene 16, producing the corresponding aryl radical cation C and 3CzCIIPN•– (E1/2 red = +1.56 V vs SCE). PC•– then reduces the azolium ion A (E1/2 = −0.81 V vs SCE) to generate the ketyl radical B, thereby closing the photoredox catalysis cycle. 2-Methoxynaphthalene produced regioselective acylation products, but heteroarene substrates produced a mixture of products, for example, furan, thiophene, and benzothiophene.

Compared to the traditional LAs-mediated Friedel–Crafts acylation, the described radical method offers a regiodivergent result with good functional group tolerance. The Lewis acid-mediated traditional Friedel–Crafts acylation of 2-methoxynaphthalene typically proceeds at the ortho positions relative to the methoxy group due to the electron-rich nature of these sites, while the meta position remains deactivated under the ionic mechanism. Notably, the present work enables the highly regioselective formation of meta-acylated ketone products 16 through a radical pathway. The NHC-catalyzed novel acylation was achieved using acyl fluorides 4 and electron-rich arenes 15 in the presence of NHC (20 mol %), photocatalyst (5 mol %), and Cs2CO3 in CH3CN at room temperature for 18 h (Scheme 6) [56].

Scheme 6: NHC-catalyzed C–H acylation of arenes and heteroarenes through photocatalysis.

Scheme 6: NHC-catalyzed C–H acylation of arenes and heteroarenes through photocatalysis.

Gao, Ye, and co-workers reported the iminoacylation of alkenes 17 via photoredox NHC dual catalysis in the presence of NHC (20 mol %), photocatalyst (5 mol %), with Na2CO3 (1.2 equiv) using a 36 W blue LED. In this method, the alkene-attached iminyl radicals A and the NHC-attached ketyl radical B are generated under photoredox NHC catalysis under visible-light irradiation. The 5-exo-trig radical cyclization of the alkene-tethered iminyl radicals A furnished a dihydropyrrole-derived radical coupled with the NHC group attached ketyl radical B. This approach features readily available starting materials, good functional group tolerance, and mild, transition-metal-free conditions. NHC-catalyzed radical approach furnishes access to substituted 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrroles 18, in good yields (Scheme 7) [57].

Scheme 7: NHC-catalyzed iminoacylation of alkenes via photoredox dual organocatalysis.

Scheme 7: NHC-catalyzed iminoacylation of alkenes via photoredox dual organocatalysis.

A novel strategy was discovered for 1,2-dicarbonylation of vinyl arenes 11, acyl fluoride 4, and keto-ester 19 via NHC/photoredox cooperative dual catalysis, which includes a radical cascade process reported by Zhu, Feng et al. The organic photoredox dual catalysis enables sequential C–C(O)OR and C–C(O)Ar bond formation, in the presence of catalytic amounts of NHC and organo-photocatalyst, leading to various β-aryl keto ester derivatives 20 in good to excellent yields. The key steps of the reactions undergo radical–radical cross-coupling with the alkyl ester radical E and benzyl radical B to afford the desired keto-esters 20 in up to 88% yield. This catalytic process displayed good functional group tolerance and broader substrate scope. The notable features of this dual catalysis approach are its mild reaction conditions, easy operation, and metal/base-free nature, which provide a valuable and facile method to rapidly access highly substituted β-aryl keto ester scaffolds 20 of interest in biological and materials sciences (Scheme 8) [58].

Scheme 8: NHC/photoredox catalyzed direct synthesis of β-arylketoesters.

Scheme 8: NHC/photoredox catalyzed direct synthesis of β-arylketoesters.

In 2025, Xuan and colleagues, for the first time, developed a visible-light-driven dual catalytic method enabling the three-component borylacylation of substituted olefins 21. This novel strategy allows the rapid and efficient preparation of boryl 1,4-dicarbonyl compounds 23, valuable boron intermediates, from readily available starting materials and catalysts. The dual catalysis, merging NHC and photocatalysts, involves an radical species B and boryl radicals D, which undergo rapid radical–radical cross-coupling to yield the borylated 1,4-dicarbonyl compounds 23 in good yields. This system showed broad synthetic scope and excellent functional group tolerance of this multicomponent borylacylation, using NHC (20 mol %) and photocatalyst (2 mol %), in K2CO3 (20 mol %) under mild conditions, further highlighting the utility and versatility of this dual catalytic strategy (Scheme 9) [59].

Scheme 9: Visible-light-driven NHC/photoredox catalyzed borylacylation of alkenes.

Scheme 9: Visible-light-driven NHC/photoredox catalyzed borylacylation of alkenes.

Organic dual catalysis enabled by visible-light-induced NHC and photoredoxcatalysts

In 2018, Miyabe et al. reported an innovative organocatalytic method for the oxidative esterification of functionalized cinnamaldehydes 24. Dual photocatalysis, employing NHC (5 mol %) and rhodamine 6G (5 mol %), promoted the facile esterification of arylvinyl aldehydes 24 with BrCCl3 (3 equiv) and K2CO3 (2.5 equiv) in MeOH under visible-light irradiation. In contrast, oxidative esterification of the formyl group was also achieved via dual photocatalysis. Furthermore, various NHCs and photocatalysts were examined, and it was found that rhodamine 6G in combination with triazolium-based NHCs bearing mesityl substituents gave the best results compared to those bearing phenyl or pentafluoroaryl rings. Rhodamine 6G also offers the best outcomes compared to other photocatalysts such as fluorescein, alizarin red S, rhodamine B, and eosin Y. Since photoexcited organophotocatalyst rhodamine 6G (Rh6G*) possesses a sufficiently positive reduction potential in its singlet excited state S1 (Ered* = +1.18 V vs SCE*). The reduced form of Rh6G•– subsequently reduces BrCCl3 to produce the CCl3 radical and Br−, due to its ground-state reduction potential (Ered = –1.14 V vs SCE in CH3CN), which is sufficiently negative for this conversion. In cycle 2, rhodamine 6G acts as a photoreductant, reducing BrCCl3 due to the adequate oxidation potential of its excited state (Eox* = –1.09 V vs SCE in CH3CN). The resulting oxidized Rh6G•+, with a ground-state oxidation potential of Eox = +1.23 V vs SCE in CH3CN. This catalysis enables an efficient and straightforward photocatalytic preparation of functionalized aryl esters 25 through a radical pathway (Scheme 10) [60].

Scheme 10: NHC-catalyzed oxidative functionalization of cinnamaldehyde.

Scheme 10: NHC-catalyzed oxidative functionalization of cinnamaldehyde.

The NHC/organophotocatalyzed oxidative Smiles rearrangement of O-aryl aldehydes 26 has been developed using oxygen as the terminal oxidant under visible-light dual catalysis. This approach afforded highly functionalized 2-hydroxyarylbenzoates 27, tolerating electron-deficient and electron-rich substituents. The C–O bond cleavage and the new C–O bond formation process were achieved using NHC (10 mol %), a photocatalyst (2 mol %), and DABCO (1.5 equiv), providing the corresponding aryl salicylates 27 in moderate to good yields. Mechanistic studies support the oxidation of the Breslow intermediate by oxygen in the presence of an acridinium photocatalyst and NaI (10 mol %) as a cocatalyst, affording an innovative method for oxidative carbene catalysis under mild conditions. Previous reports showed that 9-Mes-10-Me-acrydinium (Ered* in T1: +1.45 V vs SCE in CH3CN) exhibited more positive potentials, leading to an enhancement in chemical yields. One C–O bond was cleaved in this reaction while a new C–O bond was formed simultaneously using NHC and Mes-Acr-Me+ClO4− in DCM at rt for 13 h, leading to the formation of aryl ester compounds 27 via radical-radical cross-coupling between intermediates A and B (Scheme 11) [61].

Scheme 11: NHC/photocatalyzed oxidative Smiles rearrangement.

Scheme 11: NHC/photocatalyzed oxidative Smiles rearrangement.

Scheidt and co-workers used a tandem annulation strategy, merging NHC and organic photoredox catalysis for the convergent novel synthesis of α,β-disubstituted cyclohexyl ketone scaffolds 30. This cascade process rapidly forms two contiguous C–C bonds via a formal [5 + 1] cycloaddition. It represents a valuable approach for the α-functionalization of ketones using visible-light irradiation under mild reaction conditions. In a one-pot procedure, the reaction was carried out between alkenes 28 and coupling partner 29 in the presence of NHC (30 mol %) and a photocatalyst (5 mol %). Under these conditions organophotocatalyst (3DPAFIPN) was employed, significant amounts of cyclized product were observed and suggesting that the necessary redox potentials fall near its redox range (E1/2 PC*/PC•− to E1/2 PC/PC•− = +1.09 to −1.59 V vs SCE). This catalytic method provides an efficient route for synthesizing complex cycloalkanone scaffolds with potential applications in pharmaceutical and materials sciences (Scheme 12) [62].

Scheme 12: NHC-catalyzed synthesis of cyclohexanones through photocatalyzed annulation.

Scheme 12: NHC-catalyzed synthesis of cyclohexanones through photocatalyzed annulation.

Sumida, Ohmiya, and co-workers recently developed an NHC-and organic photoredox-catalyzed meta-selective Friedel–Crafts type acylation of electron-rich aromatic compounds 31. The described catalytic system involves the efficient nucleophilic addition of an imidazolyl anion B to radical cation species A, generated via single-electron oxidation of electron-donating arenes 31. The azolide anion B is released from acylimidazole 9 through an addition/elimination sequence in the presence of an NHC catalyst. The anticipated meta-acylation product 32 was achieved through highly selective C(sp3)–C(sp3)-radical–radical cross-coupling between the cyclohexadienyl radical C and the benzyl radical species F, formed via single-electron reduction. This photochemical method overturns the traditional ortho and para-selectivity observed in Friedel–Crafts acylation. The authors anticipate expanding this strategy to other reaction processes, allowing the efficient development of transformative synthetic methods, constructing new chemical spaces for drug discovery, and modifying bioactive molecules (Scheme 13) [63].

Scheme 13: Dual organocatalyzed meta-selective acylation of electron-rich arenes and heteroarenes using blue LED.

Scheme 13: Dual organocatalyzed meta-selective acylation of electron-rich arenes and heteroarenes using blue L...

Chauhan et al. developed a photocatalytic dual catalysis for an efficient stereoselective method that affords direct access to the pyrrolo[1,2-d][1,4]-oxazepin-3(2H)-ones 35 by merging organic eosin Y photoredox with carbene catalysis. Previous reports have shown eosin Y (Ered* in T1 [EY−•/EY*]: +0.83 V vs SCE in CH3CN), possessing less positive reduction potential, have shown the low catalytic activities of the reactions. This synergistic method permits the use of safer and non-toxic starting materials. In this relay catalytic strategy, a wide range of substituted enals 34 and dibenzoxazepines 33 worked well to achieve excellent enantioselectivities of the single diastereomers of the carbonyl products 35. This reaction was carried out using NHC (10 mol %), eosin Y (5 mol %) under mild conditions. Various functionalized dibenzothioazepine substrates have also been employed to deliver the desired polycyclic compounds 35 in a moderate level of enantioselectivity (Scheme 14) [64].

Scheme 14: Asymmetric synthesis of fused pyrrolidinones via organophotoredox/N‑heterocyclic carbene dual catalysis.

Scheme 14: Asymmetric synthesis of fused pyrrolidinones via organophotoredox/N‑heterocyclic carbene dual catal...

Conclusion

In conclusion, over the past two decades, organocatalyzed visible-light-promoted radical chemistry, particularly dual photocatalysis combining N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) with organic photocatalysts, has emerged as a versatile and robust model for the sustainable synthesis of carbonyl groups and related valued organic compounds. This cooperative photochemical strategy offers broad functional group tolerance and operational simplicity. It aligns with green chemistry principles by operating under mild conditions, using sustainable methods with low-cost materials, and using non-toxic reagents. Its proven potential includes medicinal chemistry, pharmaceuticals, materials science, and the late-stage functionalization of complex bioactive molecules. Recent synthetic advances in methodology development, mechanistic understanding, and obtained results are expected to expand the applicability of NHC-photoredox dual or triple catalysis, enabling the efficient and eco-friendly synthesis of increasingly complex molecular architectures.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data was generated or analyzed in this study.

References

-

Melchiorre, P. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1483–1484. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00993

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pitre, S. P.; Overman, L. E. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1717–1751. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00247

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kwon, K.; Simons, R. T.; Nandakumar, M.; Roizen, J. L. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2353–2428. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00444

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheung, K. P. S.; Sarkar, S.; Gevorgyan, V. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1543–1625. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00403

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lechner, V. M.; Nappi, M.; Deneny, P. J.; Folliet, S.; Chu, J. C. K.; Gaunt, M. J. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1752–1829. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00357

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Candish, L.; Collins, K. D.; Cook, G. C.; Douglas, J. J.; Gómez-Suárez, A.; Jolit, A.; Keess, S. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2907–2980. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00416

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, Q.; Gogoi, A. R.; Rentería-Gómez, Á.; Gutierrez, O.; Scheidt, K. A. Chem 2023, 9, 1983–1993. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2023.04.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Juliá, F.; Constantin, T.; Leonori, D. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2292–2352. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00558

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Buglioni, L.; Raymenants, F.; Slattery, A.; Zondag, S. D. A.; Noël, T. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2752–2906. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00332

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Großkopf, J.; Kratz, T.; Rigotti, T.; Bach, T. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1626–1653. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00272

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Genzink, M. J.; Kidd, J. B.; Swords, W. B.; Yoon, T. P. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1654–1716. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00467

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Crisenza, G. E. M.; Melchiorre, P. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 803. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13887-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mavroskoufis, A.; Jakob, M.; Hopkinson, M. N. ChemPhotoChem 2020, 4, 5147–5153. doi:10.1002/cptc.202000120

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Yang, R.; Song, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 13367–13383. doi:10.1039/d3sc03274d

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Tian, K.; Xia, Z.-F.; Wei, J.; Tao, H.-Y.; Dong, X.-Q. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 6243–6264. doi:10.1039/d4qo01335b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Marzo, L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 4603–4610. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202100261

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Knight, R. L.; Leeper, F. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 1891–1894. doi:10.1039/a803635g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, M.; Struble, J. R.; Bode, J. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8418–8420. doi:10.1021/ja062707c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, Q.; Perreault, S.; Rovis, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14066–14067. doi:10.1021/ja805680z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Biju, A. T.; Kuhl, N.; Glorius, F. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 1182–1195. doi:10.1021/ar2000716

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Enders, D.; Kallfass, U. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1743–1745. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1743::aid-anie1743>3.0.co;2-q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rafiński, Z.; Kozakiewicz, A.; Rafińska, K. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 1404–1408. doi:10.1021/cs500207d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jang, K. P.; Hutson, G. E.; Johnston, R. C.; McCusker, E. O.; Cheong, P. H.-Y.; Scheidt, K. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 76–79. doi:10.1021/ja410932t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Baragwanath, L.; Rose, C. A.; Zeitler, K.; Connon, S. J. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 9214–9217. doi:10.1021/jo902018j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fu, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhu, T.; Leong, W. W. Y.; Chi, Y. R. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 835–839. doi:10.1038/nchem.1710

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dhayalan, V.; Gadekar, S. C.; Alassad, Z.; Milo, A. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 543–551. doi:10.1038/s41557-019-0258-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gadekar, S. C.; Dhayalan, V.; Nandi, A.; Zak, I. L.; Mizrachi, M. S.; Kozuch, S.; Milo, A. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 14561–14569. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c04583

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Thai, K.; Langdon, S. M.; Bilodeau, F.; Gravel, M. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2214–2217. doi:10.1021/ol400769t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Langdon, S. M.; Wilde, M. M. D.; Thai, K.; Gravel, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7539–7542. doi:10.1021/ja501772m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hopkinson, M. N.; Richter, C.; Schedler, M.; Glorius, F. Nature 2014, 510, 485–496. doi:10.1038/nature13384

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arduengo, A. J., III; Harlow, R. L.; Kline, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 361–363. doi:10.1021/ja00001a054

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Berkessel, A.; Elfert, S.; Yatham, V. R.; Neudörfl, J.-M.; Schlörer, N. E.; Teles, J. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 12370–12374. doi:10.1002/anie.201205878

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Flanigan, D. M.; Romanov-Michailidis, F.; White, N. A.; Rovis, T. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9307–9387. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00060

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dzieszkowski, K.; Barańska, I.; Mroczyńska, K.; Słotwiński, M.; Rafiński, Z. Materials 2020, 13, 3574. doi:10.3390/ma13163574

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Menon, R. S.; Biju, A. T.; Nair, V. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 444–461. doi:10.3762/bjoc.12.47

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sharma, D.; Chatterjee, R.; Dhayalan, V.; Dandela, R. Synthesis 2022, 54, 4129–4166. doi:10.1055/a-1856-5688

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alassad, Z.; Nandi, A.; Kozuch, S.; Milo, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 89–98. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c08302

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuwano, S.; Harada, S.; Kang, B.; Oriez, R.; Yamaoka, Y.; Takasu, K.; Yamada, K.-i. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11485–11488. doi:10.1021/ja4055838

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Enders, D.; Niemeier, O.; Henseler, A. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5606–5655. doi:10.1021/cr068372z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jia, M.-Q.; You, S.-L. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 622–624. doi:10.1021/cs4000014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Carson, W. P., II; Tsymbal, A. V.; Pipal, R. W.; Edwards, G. A.; Martinelli, J. R.; Cabré, A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 15681–15687. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c04477

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Plunkett, S.; Diccianni, J. B.; Mulhearn, J.; Choi, S. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 11689–11694. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5c03643

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tu, T.; Nie, G.; Zhang, T.; Hu, C.; Ren, S.-C.; Xia, H.; Chi, Y. R. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 11088–11091. doi:10.1039/d4cc03257h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Peng, X.; Liao, T.; Chen, D.; Tu, T.; Liu, D.; Cheng, Z.; Huang, S.; Ren, S.-C.; Zhang, X.; Chi, Y. R. Sci. China: Chem. 2025, 68, 3611–3621. doi:10.1007/s11426-024-2481-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

DiRocco, D. A.; Rovis, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8094–8097. doi:10.1021/ja3030164

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, B.; Qi, J.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 279–283. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03941

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hopkinson, M. N.; Mavroskoufis, A. Synlett 2021, 32, 95–101. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1706472

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, K.; Schwenzer, M.; Studer, A. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 11984–11999. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c03996

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Singha, S.; Serrano, E.; Mondal, S.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Glorius, F. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 48–54. doi:10.1038/s41929-019-0387-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tian, K.; Xiang, F.; Huang, J.-L.; Song, Y.-W.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.-J.; Dong, X.-Q. Sci. China: Chem. 2025, 68, 5776–5786. doi:10.1007/s11426-025-2680-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, M.-S.; Shu, W. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 12960–12966. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c04070

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zuo, Z.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Studer, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25252–25257. doi:10.1002/anie.202110304

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meng, Q.-Y.; Lezius, L.; Studer, A. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2068. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22292-z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, P.; Fitzpatrick, K. P.; Scheidt, K. A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 518–524. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101354

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takemura, N.; Sumida, Y.; Ohmiya, H. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 7804–7810. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c01964

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reimler, J.; Yu, X.-Y.; Spreckelmeyer, N.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Studer, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303222. doi:10.1002/anie.202303222

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, Y.-X.; Zhang, C.-L.; Gao, Z.-H.; Ye, S. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 855–860. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Fan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, Y.-S. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 3288–3292. doi:10.1039/d3qo00515a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Z.-L.; Ma, S.-C.; Tang, S.-Y.; Yu, H.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xuan, J. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 7101–7111. doi:10.1021/acscatal.5c01396

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshioka, E.; Inoue, M.; Nagoshi, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Mizobuchi, R.; Kawashima, A.; Kohtani, S.; Miyabe, H. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 8962–8970. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b01099

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xia, Z.-H.; Dai, L.; Gao, Z.-H.; Ye, S. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1525–1528. doi:10.1039/c9cc09272b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bay, A. V.; Farnam, E. J.; Scheidt, K. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7030–7037. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c13105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Goto, Y.; Sano, M.; Sumida, Y.; Ohmiya, H. Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 1037–1045. doi:10.1038/s44160-023-00378-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hussain, Y.; Sharma, D.; Tamanna; Chauhan, P. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 2520–2524. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00685

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 57. | Dong, Y.-X.; Zhang, C.-L.; Gao, Z.-H.; Ye, S. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 855–860. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00006 |

| 58. | Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Fan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, Y.-S. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 3288–3292. doi:10.1039/d3qo00515a |

| 59. | Chen, Z.-L.; Ma, S.-C.; Tang, S.-Y.; Yu, H.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xuan, J. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 7101–7111. doi:10.1021/acscatal.5c01396 |

| 1. | Melchiorre, P. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1483–1484. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00993 |

| 2. | Pitre, S. P.; Overman, L. E. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1717–1751. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00247 |

| 3. | Kwon, K.; Simons, R. T.; Nandakumar, M.; Roizen, J. L. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2353–2428. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00444 |

| 4. | Cheung, K. P. S.; Sarkar, S.; Gevorgyan, V. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1543–1625. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00403 |

| 5. | Lechner, V. M.; Nappi, M.; Deneny, P. J.; Folliet, S.; Chu, J. C. K.; Gaunt, M. J. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1752–1829. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00357 |

| 6. | Candish, L.; Collins, K. D.; Cook, G. C.; Douglas, J. J.; Gómez-Suárez, A.; Jolit, A.; Keess, S. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2907–2980. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00416 |

| 17. | Knight, R. L.; Leeper, F. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 1891–1894. doi:10.1039/a803635g |

| 28. | Thai, K.; Langdon, S. M.; Bilodeau, F.; Gravel, M. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2214–2217. doi:10.1021/ol400769t |

| 29. | Langdon, S. M.; Wilde, M. M. D.; Thai, K.; Gravel, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7539–7542. doi:10.1021/ja501772m |

| 13. | Mavroskoufis, A.; Jakob, M.; Hopkinson, M. N. ChemPhotoChem 2020, 4, 5147–5153. doi:10.1002/cptc.202000120 |

| 14. | Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Yang, R.; Song, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 13367–13383. doi:10.1039/d3sc03274d |

| 15. | Tian, K.; Xia, Z.-F.; Wei, J.; Tao, H.-Y.; Dong, X.-Q. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 6243–6264. doi:10.1039/d4qo01335b |

| 16. | Marzo, L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 4603–4610. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202100261 |

| 30. | Hopkinson, M. N.; Richter, C.; Schedler, M.; Glorius, F. Nature 2014, 510, 485–496. doi:10.1038/nature13384 |

| 12. | Crisenza, G. E. M.; Melchiorre, P. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 803. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13887-8 |

| 25. | Fu, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhu, T.; Leong, W. W. Y.; Chi, Y. R. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 835–839. doi:10.1038/nchem.1710 |

| 64. | Hussain, Y.; Sharma, D.; Tamanna; Chauhan, P. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 2520–2524. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00685 |

| 7. | Peng, Q.; Gogoi, A. R.; Rentería-Gómez, Á.; Gutierrez, O.; Scheidt, K. A. Chem 2023, 9, 1983–1993. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2023.04.011 |

| 8. | Juliá, F.; Constantin, T.; Leonori, D. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2292–2352. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00558 |

| 9. | Buglioni, L.; Raymenants, F.; Slattery, A.; Zondag, S. D. A.; Noël, T. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2752–2906. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00332 |

| 10. | Großkopf, J.; Kratz, T.; Rigotti, T.; Bach, T. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1626–1653. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00272 |

| 11. | Genzink, M. J.; Kidd, J. B.; Swords, W. B.; Yoon, T. P. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1654–1716. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00467 |

| 26. | Dhayalan, V.; Gadekar, S. C.; Alassad, Z.; Milo, A. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 543–551. doi:10.1038/s41557-019-0258-1 |

| 27. | Gadekar, S. C.; Dhayalan, V.; Nandi, A.; Zak, I. L.; Mizrachi, M. S.; Kozuch, S.; Milo, A. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 14561–14569. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c04583 |

| 21. | Enders, D.; Kallfass, U. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1743–1745. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1743::aid-anie1743>3.0.co;2-q |

| 23. | Jang, K. P.; Hutson, G. E.; Johnston, R. C.; McCusker, E. O.; Cheong, P. H.-Y.; Scheidt, K. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 76–79. doi:10.1021/ja410932t |

| 62. | Bay, A. V.; Farnam, E. J.; Scheidt, K. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7030–7037. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c13105 |

| 20. | Biju, A. T.; Kuhl, N.; Glorius, F. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 1182–1195. doi:10.1021/ar2000716 |

| 24. | Baragwanath, L.; Rose, C. A.; Zeitler, K.; Connon, S. J. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 9214–9217. doi:10.1021/jo902018j |

| 63. | Goto, Y.; Sano, M.; Sumida, Y.; Ohmiya, H. Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 1037–1045. doi:10.1038/s44160-023-00378-4 |

| 19. | Liu, Q.; Perreault, S.; Rovis, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14066–14067. doi:10.1021/ja805680z |

| 60. | Yoshioka, E.; Inoue, M.; Nagoshi, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Mizobuchi, R.; Kawashima, A.; Kohtani, S.; Miyabe, H. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 8962–8970. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b01099 |

| 18. | He, M.; Struble, J. R.; Bode, J. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8418–8420. doi:10.1021/ja062707c |

| 22. | Rafiński, Z.; Kozakiewicz, A.; Rafińska, K. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 1404–1408. doi:10.1021/cs500207d |

| 61. | Xia, Z.-H.; Dai, L.; Gao, Z.-H.; Ye, S. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1525–1528. doi:10.1039/c9cc09272b |

| 38. | Kuwano, S.; Harada, S.; Kang, B.; Oriez, R.; Yamaoka, Y.; Takasu, K.; Yamada, K.-i. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11485–11488. doi:10.1021/ja4055838 |

| 39. | Enders, D.; Niemeier, O.; Henseler, A. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5606–5655. doi:10.1021/cr068372z |

| 40. | Jia, M.-Q.; You, S.-L. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 622–624. doi:10.1021/cs4000014 |

| 31. | Arduengo, A. J., III; Harlow, R. L.; Kline, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 361–363. doi:10.1021/ja00001a054 |

| 32. | Berkessel, A.; Elfert, S.; Yatham, V. R.; Neudörfl, J.-M.; Schlörer, N. E.; Teles, J. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 12370–12374. doi:10.1002/anie.201205878 |

| 33. | Flanigan, D. M.; Romanov-Michailidis, F.; White, N. A.; Rovis, T. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9307–9387. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00060 |

| 34. | Dzieszkowski, K.; Barańska, I.; Mroczyńska, K.; Słotwiński, M.; Rafiński, Z. Materials 2020, 13, 3574. doi:10.3390/ma13163574 |

| 35. | Menon, R. S.; Biju, A. T.; Nair, V. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 444–461. doi:10.3762/bjoc.12.47 |

| 36. | Sharma, D.; Chatterjee, R.; Dhayalan, V.; Dandela, R. Synthesis 2022, 54, 4129–4166. doi:10.1055/a-1856-5688 |

| 37. | Alassad, Z.; Nandi, A.; Kozuch, S.; Milo, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 89–98. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c08302 |

| 55. | Takemura, N.; Sumida, Y.; Ohmiya, H. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 7804–7810. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c01964 |

| 56. | Reimler, J.; Yu, X.-Y.; Spreckelmeyer, N.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Studer, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303222. doi:10.1002/anie.202303222 |

| 53. | Meng, Q.-Y.; Lezius, L.; Studer, A. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2068. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22292-z |

| 54. | Wang, P.; Fitzpatrick, K. P.; Scheidt, K. A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 518–524. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101354 |

| 51. | Liu, M.-S.; Shu, W. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 12960–12966. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c04070 |

| 52. | Zuo, Z.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Studer, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25252–25257. doi:10.1002/anie.202110304 |

| 13. | Mavroskoufis, A.; Jakob, M.; Hopkinson, M. N. ChemPhotoChem 2020, 4, 5147–5153. doi:10.1002/cptc.202000120 |

| 14. | Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Yang, R.; Song, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 13367–13383. doi:10.1039/d3sc03274d |

| 15. | Tian, K.; Xia, Z.-F.; Wei, J.; Tao, H.-Y.; Dong, X.-Q. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 6243–6264. doi:10.1039/d4qo01335b |

| 16. | Marzo, L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 4603–4610. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202100261 |

| 41. | Carson, W. P., II; Tsymbal, A. V.; Pipal, R. W.; Edwards, G. A.; Martinelli, J. R.; Cabré, A.; MacMillan, D. W. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 15681–15687. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c04477 |

| 42. | Plunkett, S.; Diccianni, J. B.; Mulhearn, J.; Choi, S. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 11689–11694. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5c03643 |

| 43. | Tu, T.; Nie, G.; Zhang, T.; Hu, C.; Ren, S.-C.; Xia, H.; Chi, Y. R. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 11088–11091. doi:10.1039/d4cc03257h |

| 44. | Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Peng, X.; Liao, T.; Chen, D.; Tu, T.; Liu, D.; Cheng, Z.; Huang, S.; Ren, S.-C.; Zhang, X.; Chi, Y. R. Sci. China: Chem. 2025, 68, 3611–3621. doi:10.1007/s11426-024-2481-5 |

| 45. | DiRocco, D. A.; Rovis, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8094–8097. doi:10.1021/ja3030164 |

| 46. | Zhang, B.; Qi, J.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 279–283. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03941 |

| 47. | Hopkinson, M. N.; Mavroskoufis, A. Synlett 2021, 32, 95–101. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1706472 |

| 48. | Liu, K.; Schwenzer, M.; Studer, A. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 11984–11999. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c03996 |

| 49. | Singha, S.; Serrano, E.; Mondal, S.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Glorius, F. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 48–54. doi:10.1038/s41929-019-0387-3 |

| 50. | Tian, K.; Xiang, F.; Huang, J.-L.; Song, Y.-W.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.-J.; Dong, X.-Q. Sci. China: Chem. 2025, 68, 5776–5786. doi:10.1007/s11426-025-2680-2 |

© 2025 Dhayalan; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.