Abstract

The closo-boranes BxHx+2, or their corresponding anions [BxHx]2− (where x = 5 through 12) and polycycloalkanes CnHn (where n represents even numbers from 6 through 20) exhibit a complementary relationship whereby the structures of the corresponding molecules, e.g., [B6H6]2− and C8H8 (cubane), are based on reciprocal polyhedra. The vertices in the closo-boranes correspond to faces in its polycyclic hydrocarbon counterpart and vice versa. The different bonding patterns in the two series are described. Several of these hydrocarbons (cubane, pentagonal dodecahedrane and the trigonal and pentagonal prismanes) are known while others still remain elusive. Synthetic routes to the currently known CnHn highly symmetrical polyhedral species are briefly summarized and potential routes to those currently unknown are discussed. Finally, the syntheses of the heavier element analogues of cubane and the prismanes are described.

Graphical Abstract

Review

Platonic polyhedra and the Euler relationship

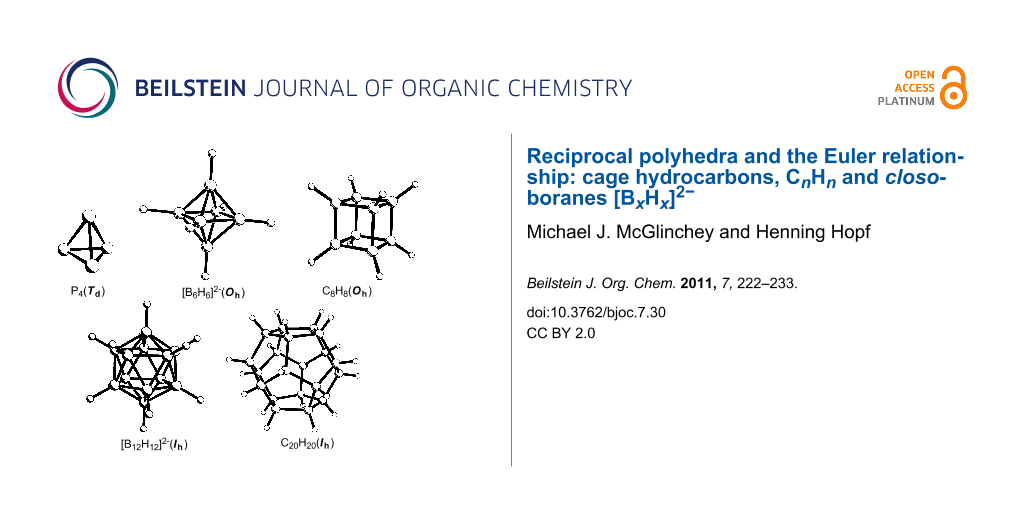

The Platonic solids have long fascinated geometers, artists and chemists alike. Molecular analogues of the tetrahedron (P4, B4Cl4, Si4t-Bu4), octahedron ([B6H6]2−), cube (C8H8), icosahedron ([B12H12]2−) and pentagonal dodecahedron (C20H20) are now known (Figure 1). The tetravalency of carbon makes the CnHn molecules viable only for the tetrahedron, cube and dodecahedron.

Figure 1: Molecular analogues of the Platonic solids.

Figure 1: Molecular analogues of the Platonic solids.

It has been recognized for millennia that there is a simple relationship between pairs of Platonic solids [1]. If the centers of adjacent faces of the octahedron are connected, they yield a cube and vice versa; this is beautifully illustrated by the X-ray crystal structure of the [Mo6Cl8]4+ cluster in which an octahedron of molybdenum atoms is encapsulated within a cube of chlorines (Figure 2). The icosahedron and pentagonal dodecahedron are similarly related; these pairs of "reciprocal" or "dual" polyhedra possess the same point group symmetry [2].

![[1860-5397-7-30-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-7-30-2.png?scale=1.7&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: The structure of [Mo6Cl8]4+ demonstrates the reciprocal relationship between the cube and the octahedron.

Figure 2: The structure of [Mo6Cl8]4+ demonstrates the reciprocal relationship between the cube and the octah...

As noted by René Descartes around 1620 and stated formally by Leonhard Euler in 1752, for any convex polyhedron there is a simple relationship between the number of vertices (V), faces (F) and edges (E):

V + F = E + 2

Thus, the cube has 8 vertices, 12 edges and 6 faces; its reciprocal polyhedron – the octahedron – possesses 6 vertices, 12 edges and 8 faces. Likewise, the V, E and F values for the icosahedron (12, 30, 20) and pentagonal dodecahedron (20, 30, 12) are in accord with Euler's equation. Interestingly, the tetrahedron (4 vertices, 6 edges and 4 faces) is its own reciprocal.

Boranes, hydrocarbons and inverse polyhedra

Closo-borane anions and their carborane analogues adopt polyhedral structures in which each face is triangular [3]; Figure 3 shows the deltahedra corresponding to the [BxHx]2−, 1–8, (x = 5 through 12) or C2Bx-2Hx series and Table 1 lists their point groups and V, E and F values. (One must emphasize that in these formally electron-deficient systems, the edges do not represent two-electron bonds but merely indicate the structure). Now, every deltahedron has a reciprocal polyhedron in which each triangular face has become a vertex linked to three neighbors; this is precisely the criterion that has to be satisfied by alkanes of the CnHn type.

Figure 3: The deltahedra corresponding to the structures of the closo-boranes [BxHx]2−.

Figure 3: The deltahedra corresponding to the structures of the closo-boranes [BxHx]2−.

Table 1: Corresponding closo-boranes and polycycloalkanes of the same symmetry.

| closo-borane | V | E | F | point group | V | E | F | polycycloalkane | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [B5H5]2− | 1 | 5 | 9 | 6 | D3h | 6 | 9 | 5 | C6H6 | [3]prismane 9 |

| [B6H6]2− | 2 | 6 | 12 | 8 | Oh | 8 | 12 | 6 | C8H8 | [4]prismane (cubane) 10 |

| [B7H7]2− | 3 | 7 | 15 | 10 | D5h | 10 | 15 | 7 | C10H10 | [5]prismane (pentaprismane) 11 |

| [B8H8]2− | 4 | 8 | 18 | 12 | D2d | 12 | 18 | 8 | C12H12 | [44.54]octahedrane 12 |

| [B9H9]2− | 5 | 9 | 21 | 14 | D3h | 14 | 21 | 9 | C14H14 | [43.56]nonahedrane 13 |

| [B10H10]2− | 6 | 10 | 24 | 16 | D4d | 16 | 24 | 10 | C16H16 | [42.58]decahedrane 14 |

| [B11H11]2− | 7 | 11 | 27 | 18 | C2v | 18 | 27 | 11 | C18H18 | [42.58.6]undecahedrane 15 |

| [B12H12]2− | 8 | 12 | 30 | 20 | Ih | 20 | 30 | 12 | C20H20 | [512]dodecahedrane 16 |

To illustrate this inverse polyhedral relationship between closo-boranes, [BxHx]2− 1–8, and CnHn hydrocarbons (n = 6, 8, 10 … 20; 9–16), the point groups and V, E, F values of the complementary CnHn molecules are collected in Table 1.

Bonding comparisons

The inverse geometric structures of the closo-boranes and their cage hydrocarbon complementary counterparts are the result of the different electronic configurations of boron and carbon. The CnHn systems are assembled from CH units each of which supplies three atomic orbitals and three electrons to the cage. Each carbon can link to three others via conventional two-electron bonds, thus forming electron-precise molecules. In contrast, BH units also provide three atomic orbitals but only two electrons for cage bonding; as a result, the closo-boranes are electron-deficient molecules with skeletal connectivities greater than three. Their total number of skeletal electron pairs equals the number of vertices plus one; for example, [B6H6]2− has 7 skeletal electron pairs and is three-dimensionally aromatic. In contrast, in the CnHn cages the number of skeletal electron pairs equals the number of edges. In terms of the Euler equation (V + F = E + 2), for cage hydrocarbons, 2E = 3V, as exemplified by cubane, C8H8, which has 12 edges and 8 vertices, whereas for closo-boranes it is evident that 2E = 3F, as in [B8H8]2− which has 18 edges and 12 faces.

However, one must not assume that bonds are fragile in molecules for which the ratio of valence electrons to interatomic linkages is less than two. For example, the carborane 1,12-B10C2H12 (an icosahedral molecule in which the carbons are maximally separated) only suffers serious decomposition at 630 °C [4], a temperature very much higher than that at which the vast majority of electron-precise organic molecules would survive.

The existence of a complete set of closo-boranes, BxHx+2, or their corresponding anions [BxHx]2−, where x = 5 through 12, suggests that their complementary hydrocarbon cages CnHn, where n represents the even numbers 4 through 20, should also all be viable, as discussed herein.

Synthetic routes to highly symmetrical polycyclic hydrocarbons

As already noted, molecular analogues of the Platonic solids are known, and the first syntheses of cubane, 10, (by Philip Eaton) [5], and of pentagonal dodecahedrane, 16, (by Leo Paquette) [6,7] are now classics. [3]Prismane, C6H6, 9, (by Tom Katz) and [5]prismane, C10H10, 11, (also by Eaton) have been reported, but the remaining hydrocarbons listed in Table 1 still pose serious synthetic challenges. Here, we briefly summarize the successful routes to 9, 10, 11 and 16, include selected publications on the synthesis of derivatives of tetrahedrane, discuss the current status of some "polycycloalkane near misses", and suggest that a C2v isomer of C18H18, 15, should be a worthwhile synthetic target.

Tetrahedrane, C4H4

The search for tetrahedrane has a long history [8] and the parent molecule still resists isolation. However, Maier and co-workers were able to prepare the tetra-tert-butyl derivative, 19, as the first known derivative of this simplest of the Platonic bodies by photolysis of tetra-tert-butylcyclopentadienone, (17). As depicted in Scheme 1, the initial "criss-cross" product, 18, eventually loses CO to yield 19, as a stable crystalline material [9]. Presumably, in addition to the unfavorable electronic factors associated with cyclobutadienes, steric interactions between the bulky alkyl groups destabilize the planar system. However, the formation of a molecule containing four cyclopropyl moieties clearly introduces considerable additional ring strain.

Scheme 1: The first synthesis of a tetrahedrane 19 by Maier.

Scheme 1: The first synthesis of a tetrahedrane 19 by Maier.

[3]Prismane, C6H6, 9

Prismane derivatives bearing bulky substituents (e.g., t-Bu, CF3, Ph; 20) have been available for more than three decades via photolysis of sterically encumbered benzenes [10]. The marked deviation from planarity in these systems favors the formation of Dewar benzenes, 21, which undergo [2 + 2] cycloadditions to produce the prismane skeleton, 22, (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: The conversion of Dewar benzenes to [3]-prismanes.

Scheme 2: The conversion of Dewar benzenes to [3]-prismanes.

However, the parent prismane, 9, proved much more elusive and was finally obtained in 2% yield by treatment of benzvalene, (23), with N-phenyltriazolindione, (24), to give cycloadduct 25; conversion to the azo compound 26 and photolysis to extrude nitrogen finally led to 9 [11] (Scheme 3). Although the yield of the final photolysis step has now been improved somewhat to 15% [12], [3]prismane is still not a conveniently obtainable molecule.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of [3]prismane 9 by Katz.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of [3]prismane 9 by Katz.

Cubane, C8H8, 10

The key step of Eaton's beautiful synthesis of [4]prismane (cubane, 10), shown in Scheme 4, involves the ring contraction of the mono-protected diketone 28, itself available via photolysis of 27, the mono-ketal of the Diels–Alder dimer of 2-bromocyclopentadienone. At this point, the bishomocubanedione system is exquisitely poised to undergo successive Favorskii reactions to yield eventually the carboxylic acid 29, which furnishes cubane upon decarboxylation [5].

Scheme 4: Synthesis of cubane 10 by Eaton.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of cubane 10 by Eaton.

An elegant modification of this procedure has been reported by Pettit [13] who used (cyclobutadiene)Fe(CO)3, (30), as the source of one of the square faces (Scheme 5). Once again, as in Eaton's procedure, two Favorski ring contractions were used to obtain the cubane skeleton, first in the form of the dicarboxylic acid 33 which on subsequent decarboxylation gave 10.

Scheme 5: Synthesis of cubane 10 by Pettit.

Scheme 5: Synthesis of cubane 10 by Pettit.

The original approach has since been considerably improved and modified. Now, functionalized cubanes can be obtained in kilogram quantities and their chemistry has been extensively studied. For example, polynitrocubanes have been investigated as high-energy-density materials [14,15] and the cardiopharmacological activity of cubane dicarboxylic acid and its amide has been reported [16].

[5]Prismane, C10H10, 11

Since pentaprismane, 11, is the least strained of the prismanes, one might have expected it to be readily available by photolytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition of hypostrophene, 34, or by extrusion of nitrogen from either 35 or 36, as in Scheme 6 [17-20]; surprisingly, all these routes were found to be ineffective.

Scheme 6: Failed routes to [5]-prismane 11.

Scheme 6: Failed routes to [5]-prismane 11.

Success was finally achieved via ring contraction of a homopentaprismane, somewhat analogous to the original cubane synthesis. As shown in Scheme 7, Diels–Alder reaction of 1,2,3,4-tetrachloro-5,5-dimethoxycyclopentadiene with p-benzoquinone gave 37 which underwent photolytic [2 + 2] closure to the pentacyclic dione 38. Subsequent dechlorination and functional group manipulation led to the iodo-tosylate 39 which, in the presence of base, generated the homohypostrophene, 40; [2 + 2] cycloaddition then furnished the homopentaprismanone 41. Introduction of a bridge head bromine (with the intent of carrying out a Favorskii ring contraction) proved to be impossible. Instead it was necessary to proceed via the keto-ester 42 and the dihydroxyhomopentaprismane 43 which, after ring contraction and decarboxylation, yielded 11 [21,22].

Scheme 7: Synthesis of [5]prismane 11 by Eaton.

Scheme 7: Synthesis of [5]prismane 11 by Eaton.

Pentagonal dodecahedrane, C20H20, 16

The preparation of dodecahedrane, 16, is undoubtedly one of the great synthetic achievements of recent times and will remain at the forefront of alicyclic chemistry until a stepwise synthesis of C60 is achieved. However, we note en passant that Scott, de Meijere and their colleagues have devised a rational route to C60 from a chlorinated precursor, C60H27Cl3, in which only the final ring closures were achieved via preparative-scale flash vacuum pyrolysis [23].

The icosahedral point group possesses ten C3 axes and six C5 axes, and synthetic proposals have taken advantage of both types of symmetry elements. The former prompted Woodward [24] and Jacobson [25] independently from each other to suggest that two triquinacene units could be coupled (Scheme 8). The requisite C10H10 moiety, 44, has been prepared (most elegantly via Paquette’s domino Diels–Alder route [26]) but all attempts at controlled dimerization (even on a transition metal template [27]) have so far proven fruitless. A second approach is based upon the five-fold symmetry of [5]peristylane, 46; this system has been accessed by Eaton (Scheme 8) but attempts to add the 5-carbon roof, 45, have not yet succeeded [28]. Another "3-fold" approach relies on the addition of a trimethylenemethane-like C4 fragment, 47, to C16-hexaquinacene, 48; but again complications arose during attempts to convert this molecule to 16 [29].

Scheme 8: Retrosynthetic analysis for several approaches to dodecahedrane 16.

Scheme 8: Retrosynthetic analysis for several approaches to dodecahedrane 16.

As outlined in Paquette's eloquent overview of the history of the dodecahedrane project [30], success was finally achieved via the C2 route summarized in Scheme 9. The crucial intermediate, 49, was hydrogenated to 50, which was converted in several cyclization steps to the diol 51. Oxidation and condensation of the resulting ketoaldehyde then provided the mono ketone 52, which was photochemically ring-closed to the secododecahedrene 53. After diimine hydrogenation to 54 only one C–C bond in the nearly completed sphere was lacking. This final cyclodehydrogenation to 16 was accomplished by treatment of 54 with Pt/C at 250 °C [31,32].

Scheme 9: Paquette´s synthesis of dodecahedrane 16.

Scheme 9: Paquette´s synthesis of dodecahedrane 16.

Subsequently, Prinzbach established an entirely different route to dodecahedrane (Scheme 10) that proceeds by catalytic isomerization of pagodane, 55, a molecule of D2h symmetry, which itself was prepared by a multi-step route from readily available starting materials. Alternatively, the bis-cyclopropanated hydrocarbon 56 yielded dodecahedrane on treatment with Pd/C in a hydrogen atmosphere. Once again, the reader is referred to Prinzbach's comprehensive review of his group's major contributions to this area [33].

Scheme 10: Prinzbach´s synthesis of dodecahedrane 16.

Scheme 10: Prinzbach´s synthesis of dodecahedrane 16.

Currently unknown polyhedranes, CnHn, n = 12, 14, 16, 18

After this short overview of the successful syntheses of several polycyclic alkanes, CnHn, where n = 4, 6, 8, 10 and 20, we now turn to the remaining unknown polyhedranes for which n = 12 (octahedrane, 12), n = 14 (nonahedrane, 13), n = 16 (decahedrane, 14), and n = 18 (undecahedrane, 15) (Figure 4). Although none of these have as yet been reported, there is some beautiful chemistry associated with their potential precursors, and one can only admire the ingenuity of the talented investigators in this area.

Figure 4: The as yet unknown polyhedranes 12–15.

Figure 4: The as yet unknown polyhedranes 12–15.

Octahedrane, C12H12, 12

One might envisage a direct route to 12 by the coupling of two Dewar benzenes as in 57 (Figure 5), but we are unaware of any such reports.

Figure 5: Coupling of two Dewar benzenes.

Figure 5: Coupling of two Dewar benzenes.

However, metal carbonyl promoted dimerization of norbornadienes, e.g., 58 to 59, is a well established protocol, and Marchand [34] has exploited this reaction to prepare the C14 diketone 60 (Scheme 11). In principle, one could incorporate bridgehead halogens as in 61 with the aim of carrying out two Favorskii ring contractions to generate the octahedrane skeleton, viz. the dicarboxylic acid 62, which ultimately would then require to be decarboxylated to produce the parent system 12. More realistically, one can see the obvious similarity to the conversion of homopenta-prismanone, 41, to pentaprismane, 11, which was successfully accomplished via Baeyer–Villiger oxidation, acyloin coupling and decarboxylation. Thus, one might anticipate that such an approach might provide access to D2d [44.54]octahedrane 12. (We note that a simplified nomenclature has been proposed in which the number of 3, 4 or 5-membered rings is indicated by a superscript; thus cubane is [46]hexahedrane and pentaprismane is [45.52]heptahedrane [35]).

Scheme 11: A possible route to octahedrane 12.

Scheme 11: A possible route to octahedrane 12.

Nonahedrane, C14H14, 13

It has been proposed that an intermediate in the synthesis of [5]peristylane may be a viable precursor to the still unknown D3h [43.56]nonahedrane, (13). As shown in Scheme 12, the diene-dione 63 can be readily converted to the double enone 64 which undergoes [2 + 2] photocyclization to yield the pentacyclic diketone 65 [36]. We await further elaboration of this fascinating system.

Scheme 12: A possible route to nonahedrane 13.

Scheme 12: A possible route to nonahedrane 13.

Decahedrane, C16H16, 14

Formally, 14 should be available by capping [4]peristylane with a four-membered ring system, as in 66 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Capping [4]peristylane with a four-membered ring system.

Figure 6: Capping [4]peristylane with a four-membered ring system.

However, to translate this concept into a preparatively realistic protocol is a different matter. Even if there is no report of a completed synthesis of 14, considerable progress has been made [37]. The route taken by Paquette and co-workers (Scheme 13) required the initial generation of the fulvene 67, whose four-membered ring should eventually serve as the "roof" of a [4]peristylane "building". Towards this goal, 67 was first converted into the cyclopentadiene derivative 68, whose carbon skeleton was subsequently extended, and then bent into a convex shape by an epoxidation reaction (formation of 69). After the still saturated C2-bridge had been reduced to an etheno bridge, the prerequisite for an intramolecular [2 + 2] photoaddition had been created. Indeed, photochemical ring closure and various oxidation steps led to the "open" triketone 70 that in principle should be convertible to a seco-decahedrane skeleton by two aldol condensations. This latter system should close to 14 by taking advantage of methodology established during the dodecahedrane project.

Scheme 13: A possible route to decahedrane 14.

Scheme 13: A possible route to decahedrane 14.

Undecahedrane, C18H18, 15

The reciprocal polyhedron to the octadecahedron B11H112−, 7, is the C2v [42.58.6]undecahedrane, 15 (Figure 7). Note that this C18H18 system contains a 6-membered ring paralleling the C2v symmetry of the borane that has a capping boron linked to six others. We are unaware of any attempted syntheses of this molecule but, as depicted in Scheme 14, suitable disconnections reveal that a C3-bridged ansa-[5]peristylane is an enticing precursor to 15.

Figure 7: A possible route to undecahedrane 15 (left: side view; right: top view).

Figure 7: A possible route to undecahedrane 15 (left: side view; right: top view).

Scheme 14: Synthetic routes to trigonal prismatic hexasilanes 71a and hexagermanes 71b.

Scheme 14: Synthetic routes to trigonal prismatic hexasilanes 71a and hexagermanes 71b.

Highly symmetric inorganic polyhedranes

The major synthetic challenges that needed to be overcome to synthesize the polyhedranes [3]prismane, (9), cubane, 10, and [5]prismane, 11, contrast sharply with the ready availability of their heavier congeners. Thus, trigonal prismatic hexasilanes, 71a, and hexagermanes, 71b, are accessible in single-step processes by sodium- or magnesium-mediated dehalogenation of the appropriate REX3 precursor, where R is a very bulky alkyl or aryl group, and X is chlorine or bromine [38,39]. The hexatellurium cation, [Te6]4+, is also trigonal prismatic [40,41].

Similarly, the inorganic cubane analogues R8E8, where E = Si, 72, and E = Ge, 73, where R is again a bulky group, are also well-known (Scheme 15). Indeed, octakis(t-butyldimethylsilyl)octasilane, (72a), is obtained in 72% yield by treatment of the corresponding trichlorosilane precursor with sodium in toluene at 90 °C. These systems have been thoroughly investigated structurally and spectroscopically, and their reactivity has also been extensively investigated [42-45]. Furthermore, as shown in Scheme 16, the octastannacubane, 75, and the per-arylated decastannane, 76, a tin analogue of pentaprismane (11) have been prepared by thermolysis of hexakis(2,6-diethylphenyl)cyclotristannne, 74, and fully characterized spectroscopically and by X-ray crystallography [46-48].

Scheme 15: Synthetic routes to octasila- and octagerma-cubanes.

Scheme 15: Synthetic routes to octasila- and octagerma-cubanes.

Scheme 16: Synthesis of an octastannacubane and a decastannapentaprismane.

Scheme 16: Synthesis of an octastannacubane and a decastannapentaprismane.

The major mitigating factor here is that such elements commonly form structures in which 90° angles are the norm [49], and so ring strain is no longer such a major impediment to bond formation. While the intrinsic yields of these products can range from very good to rather poor, this is compensated by the fact that they involve short syntheses from relatively inexpensive starting materials.

Another particularly interesting system is the mixed carbon-phosphorus heterocubane, 78, prepared in 8% yield simply by heating the phosphaalkyne t-BuC≡P, 77, at 130 °C for several days (Scheme 17) [50]. Finally, we note an interesting recent paper that reported high level theoretical calculations on the structures and stabilities of heterocubanes [XY]4 comprised of Group 13 (X = B, Al, Ga) – Group 15 (Y = N, P, As) tetramers [51]. It was shown that they should be stabilized when decorated with donor–acceptor linkages as in 79. Moreover, it was suggested that they may function as single source precursors of Group 13 – Group 15 materials with applications in microelectronics.

Conclusion

We have endeavored to illustrate the complementary relationship between closo-boranes [BxHx]2−, where x = 5 through 12, and polycycloalkanes CnHn, where n represents even numbers from 6 through 20. Several of these hydrocarbons are known while others remain elusive. Interestingly, one can invert the original concept and propose that other highly symmetrical cage hydrocarbons of the CnHn type might have closo-borane counterparts. Indeed, Lipscomb and Massa have discussed the structures of borane analogues of fullerenes [52,53] and even of nanotubes [54]. In particular, they proposed that C60 (V, E, F = 60, 90, 32) could have a corresponding closo-borane [B32H32]2− (V, E, F = 32, 90, 60) of icosahedral symmetry [55].

Similarly, in the C8H8 series, de Meijere [56] has prepared D3d [32.56]octahedrane, 80, (Figure 8; V, E, F = 12, 18, 8), and one might envisage the existence of a comparable "electron deficient" molecule of bicapped octahedral symmetry (V, E, F = 8, 18, 12); indeed, Muetterties noted that D2d [B8H8]2− is highly fluxional and exists in equilibrium with several other isomers [57,58]. Moreover, transition metal clusters, such as [Re8C(CO)24]2−, provide examples of such a bicapped octahedral D3d geometry [59]. Interestingly, King et al. have pointed out the reciprocal polyhedral relationship between gold clusters and fullerenes [60].

Figure 8: D3d symmetric C8H8, a bis-truncated cubane.

Figure 8: D3d symmetric C8H8, a bis-truncated cubane.

As noted above, molecular analogues of several members of both sets of the complementary polyhedra exhibited by the closo-boranes and by the polycycloalkanes have been constructed from other elemental species: Clusters containing lithium, transition metals, silicon, phosphorus, arsenic, bismuth, lead, etc. have been characterized [61-64], and their architectures continue to delight us. The existence of molecules of such exquisite symmetry would surely have fascinated Plato.

References

-

Plato Timaeus (ca. 350 B.C.)

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Coxeter, H. S. M. Regular Polytopes; Dover: New York, 1973.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wade, K. Electron Deficient Compounds; Nelson: London, U.K., 1971; Chapter 3, p 51.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wade, K. Electron Deficient Compounds; Nelson: London, U.K., 1971; Chapter 6, p 155.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eaton, P. E.; Cole, T. W., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3157–3158. doi:10.1021/ja01069a041

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ternansky, R. J.; Balogh, D. W.; Paquette, L. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 4503–4504. doi:10.1021/ja00380a040

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paquette, L. A.; Ternansky, R. J.; Balogh, D. W.; Kentgen, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 5446–5450. doi:10.1021/ja00354a043

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hopf, H. Classics in Hydrocarbon Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000; pp 54–60.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maier, G.; Pfriem, S.; Schäfer, U.; Matusch, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1978, 17, 520–521. doi:10.1002/ange.19780900714

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mehta, G.; Padma, S. In Carbocyclic Cage Compounds; Osawa, E.; Yonemitsu, O., Eds.; VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1992; pp 189–191.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Katz, T. J.; Acton, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 2738–2739. doi:10.1021/ja00789a084

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Turro, N. J.; Ramamurthy, V.; Katz, T. J. Nouv. J. Chim. 1977, 1, 363–365.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barborak, J. C.; Watts, L.; Pettit, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 86, 1328–1329. doi:10.1021/ja00958a050

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eaton, P. E.; Ravi Shankar, B. K.; Price, G. D.; Pluth, J. J.; Gilbert, E. E.; Alster, J.; Sandus, O. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 185–186. doi:10.1021/jo00175a044

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bashir-Hashemi, A.; Iyer, S.; Alster, J.; Slagg, N. Chem. Ind. 1955, 551–555.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eremenko, L. T.; Romanova, L. B.; Ivanova, M. E.; Nesterenko, D. A.; Malygina, V. S.; Eremeev, A. B.; Logodzinskaya, G. V.; Lodygina, V. P. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1998, 47, 1137–1140. doi:10.1007/BF02503486

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, K.-W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 3064–3066. doi:10.1021/ja00741a052

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Allred, E. L.; Beck, B. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974, 15, 437–440. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)82236-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McKennis, J. S.; Brener, L.; Ward, J. S.; Pettit, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 4957–4958. doi:10.1021/ja00748a076

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paquette, L. A.; Davis, R. F.; James, D. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974, 15, 1615–1618. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)82534-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eaton, P. E.; Or, Y. S.; Branka, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 2134–2136. doi:10.1021/ja00398a062

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eaton, P. E.; Or, Y. S.; Branka, S. J.; Ravi Shankar, B. K. Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 1621–1631. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87579-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scott, L. T.; Boorum, M. M.; McMahon, B. J.; Hagen, S.; Mack, J.; Blank, J.; Wegner, H.; de Meijere, A. Science 2002, 295, 1500–1503. doi:10.1126/science.1068427

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Woodward, R. B.; Fununaga, T.; Kelly, R. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3162–3164. doi:10.1021/ja01069a046

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jacobson, I. T. Acta Chem. Scand. 1967, 21, 2235–2246. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.21-2235

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paquette, L. A.; Wyvratt, M. J.; Berk, H. C.; Moerck, R. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 5845–5855. doi:10.1021/ja00486a042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Codding, P. W.; Kerr, K. A.; Oudeman, A.; Sorensen, T. S. J. Organomet. Chem. 1982, 232, 193–199. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)89062-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eaton, P. E.; Bunnelle, W. H.; Engel, P. Can. J. Chem. 1984, 62, 2612–2626. doi:10.1139/v84-444

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sobczak, R. L.; Osborn, M. E.; Paquette, L. A. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 4886–4890. doi:10.1021/jo00394a030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paquette, L. A. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 1051–1065. doi:10.1021/cr00095a006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paquette, L. A.; Balogh, D. W.; Usha, R.; Kountz, D.; Christoph, G. G. Science 1981, 211, 575–576. doi:10.1126/science.211.4482.575

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paquette, L. A.; Balogh, D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 774–783. doi:10.1021/ja00367a021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prinzbach, H.; Weber, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 33, 2239–2257. doi:10.1002/ange.19941062204

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marchand, A. P.; Earlywine, A. D. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 1660–1661. doi:10.1021/jo00183a037

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paquette, L. A.; Browne, A. R.; Doecke, C. W.; Williams, R. V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 4113–4115. doi:10.1021/ja00350a072

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eaton, P. E.; Srikrishna, A.; Uggieri, F. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 1728–1732. doi:10.1021/jo00184a012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, C.-C.; Paquette, L. A. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 4949–4956. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90407-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sekiguchi, A.; Yatabe, T.; Kabuto, C.; Sakurai, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 5853–5854. doi:10.1021/ja00066a075

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sekiguchi, A.; Kabuto, C.; Sakurai, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1989, 28, 55–56. doi:10.1002/ange.19891010133

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burns, R. C.; Gillespie, R. J.; Luk, W.-C.; Slim, D. R. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 3086–3094. doi:10.1021/ic50201a028

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burns, R. C.; Gillespie, R. J.; Barnes, J. A.; McGlinchey, M. J. Inorg. Chem. 1982, 21, 799–807. doi:10.1021/ic00132a065

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsumoto, H.; Higuchi, K.; Hoshino, Y.; Koike, H.; Naoi, Y.; Nagai, Y. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1988, 1083–1084. doi:10.1039/C39880001083

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sekiguchi, A.; Yatabe, T.; Kamatani, H.; Kabuto, C.; Sakurai, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 6260–6262. doi:10.1021/ja00041a063

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsumoto, H.; Higuchi, K.; Kyushin, S.; Goto, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 1354–1356. doi:10.1002/ange.19921041033

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Furukawa, K.; Fujino, M.; Matsumoto, N. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1992, 60, 2744–2745. doi:10.1063/1.106863

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sita, L. R.; Kinoshita, I. Organometallics 1990, 9, 2865–2867. doi:10.1021/om00161a008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sita, L. R.; Bickerstaff, R. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 6454–6456. doi:10.1021/ja00198a085

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sita, L. R.; Kinoshita, I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1856–1857. doi:10.1021/ja00005a074

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sekiguchi, A.; Sakurai, H. In Adv. Organometal. Chem.; Stone, F. G. A.; West, R., Eds.; Academic Press: N. Y., 1995; Vol. 37, pp 1–38.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wettling, T.; Schneider, J.; Wagner, O.; Kreiter, C. G.; Regitz, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1989, 28, 1013–1014. doi:10.1002/ange.19891010808

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Timoshkin, A. Y. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 8145–8153. doi:10.1021/ic900270c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lipscomb, W. N.; Massa, L. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 2297–2299. doi:10.1021/ic00038a002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Derecskei-Kovacs, A.; Dunlap, B. I.; Lipscomb, W. N.; Lowrey, A.; Marynick, D. S.; Massa, L. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 5617–5619. doi:10.1021/ic00103a004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gindulyte, A.; Lipscomb, W. N.; Massa, L. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 6544–6545. doi:10.1021/ic980559o

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bicerano, J.; Marynick, D. S.; Lipscomb, W. N. Inorg. Chem. 1978, 17, 3443–3453. doi:10.1021/ic50190a028

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, C.-H.; Liang, S.; Haumann, T.; Boese, R.; de Meijere, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 559–561. doi:10.1002/ange.19931050428

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Muetterties, E. L.; Wiersma, R. J.; Hawthorne, M. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 7520–7522. doi:10.1021/ja00803a060

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Muetterties, E. L.; Hoel, E. L.; Salentine, C. G.; Hawthorne, M. F. Inorg. Chem. 1975, 14, 950–951. doi:10.1021/ic50146a050

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ciani, G.; D’Alfonso, G.; Freni, M.; Romiti, P.; Sironi, A. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1982, 705–706. doi:10.1039/C39820000705

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tian, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, B.; King, R. B. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 411–414. doi:10.1021/jp066272r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Housecroft, C. E. Cluster molecules of the p-block elements; Oxford University Press: Oxford, U.K., 1994.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Corbett, J. D. In Structure and Bonding; Mingos, D. M. P., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1997; Vol. 87, pp 157–193.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Teo, B. K. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 1251–1257. doi:10.1021/ic00177a017

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Teo, B. K.; Longoni, G.; Chung, F. R. K. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 1257–1266. doi:10.1021/ic00177a018

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 34. | Marchand, A. P.; Earlywine, A. D. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 1660–1661. doi:10.1021/jo00183a037 |

| 35. | Paquette, L. A.; Browne, A. R.; Doecke, C. W.; Williams, R. V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 4113–4115. doi:10.1021/ja00350a072 |

| 36. | Eaton, P. E.; Srikrishna, A.; Uggieri, F. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 1728–1732. doi:10.1021/jo00184a012 |

| 5. | Eaton, P. E.; Cole, T. W., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3157–3158. doi:10.1021/ja01069a041 |

| 16. | Eremenko, L. T.; Romanova, L. B.; Ivanova, M. E.; Nesterenko, D. A.; Malygina, V. S.; Eremeev, A. B.; Logodzinskaya, G. V.; Lodygina, V. P. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1998, 47, 1137–1140. doi:10.1007/BF02503486 |

| 50. | Wettling, T.; Schneider, J.; Wagner, O.; Kreiter, C. G.; Regitz, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1989, 28, 1013–1014. doi:10.1002/ange.19891010808 |

| 4. | Wade, K. Electron Deficient Compounds; Nelson: London, U.K., 1971; Chapter 6, p 155. |

| 17. | Shen, K.-W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 3064–3066. doi:10.1021/ja00741a052 |

| 18. | Allred, E. L.; Beck, B. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974, 15, 437–440. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)82236-X |

| 19. | McKennis, J. S.; Brener, L.; Ward, J. S.; Pettit, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 4957–4958. doi:10.1021/ja00748a076 |

| 20. | Paquette, L. A.; Davis, R. F.; James, D. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974, 15, 1615–1618. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)82534-X |

| 3. | Wade, K. Electron Deficient Compounds; Nelson: London, U.K., 1971; Chapter 3, p 51. |

| 13. | Barborak, J. C.; Watts, L.; Pettit, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 86, 1328–1329. doi:10.1021/ja00958a050 |

| 46. | Sita, L. R.; Kinoshita, I. Organometallics 1990, 9, 2865–2867. doi:10.1021/om00161a008 |

| 47. | Sita, L. R.; Bickerstaff, R. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 6454–6456. doi:10.1021/ja00198a085 |

| 48. | Sita, L. R.; Kinoshita, I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1856–1857. doi:10.1021/ja00005a074 |

| 14. | Eaton, P. E.; Ravi Shankar, B. K.; Price, G. D.; Pluth, J. J.; Gilbert, E. E.; Alster, J.; Sandus, O. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 185–186. doi:10.1021/jo00175a044 |

| 15. | Bashir-Hashemi, A.; Iyer, S.; Alster, J.; Slagg, N. Chem. Ind. 1955, 551–555. |

| 49. | Sekiguchi, A.; Sakurai, H. In Adv. Organometal. Chem.; Stone, F. G. A.; West, R., Eds.; Academic Press: N. Y., 1995; Vol. 37, pp 1–38. |

| 10. | Mehta, G.; Padma, S. In Carbocyclic Cage Compounds; Osawa, E.; Yonemitsu, O., Eds.; VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1992; pp 189–191. |

| 40. | Burns, R. C.; Gillespie, R. J.; Luk, W.-C.; Slim, D. R. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 3086–3094. doi:10.1021/ic50201a028 |

| 41. | Burns, R. C.; Gillespie, R. J.; Barnes, J. A.; McGlinchey, M. J. Inorg. Chem. 1982, 21, 799–807. doi:10.1021/ic00132a065 |

| 9. | Maier, G.; Pfriem, S.; Schäfer, U.; Matusch, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1978, 17, 520–521. doi:10.1002/ange.19780900714 |

| 5. | Eaton, P. E.; Cole, T. W., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3157–3158. doi:10.1021/ja01069a041 |

| 42. | Matsumoto, H.; Higuchi, K.; Hoshino, Y.; Koike, H.; Naoi, Y.; Nagai, Y. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1988, 1083–1084. doi:10.1039/C39880001083 |

| 43. | Sekiguchi, A.; Yatabe, T.; Kamatani, H.; Kabuto, C.; Sakurai, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 6260–6262. doi:10.1021/ja00041a063 |

| 44. | Matsumoto, H.; Higuchi, K.; Kyushin, S.; Goto, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 1354–1356. doi:10.1002/ange.19921041033 |

| 45. | Furukawa, K.; Fujino, M.; Matsumoto, N. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1992, 60, 2744–2745. doi:10.1063/1.106863 |

| 8. | Hopf, H. Classics in Hydrocarbon Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000; pp 54–60. |

| 37. | Shen, C.-C.; Paquette, L. A. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 4949–4956. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90407-7 |

| 6. | Ternansky, R. J.; Balogh, D. W.; Paquette, L. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 4503–4504. doi:10.1021/ja00380a040 |

| 7. | Paquette, L. A.; Ternansky, R. J.; Balogh, D. W.; Kentgen, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 5446–5450. doi:10.1021/ja00354a043 |

| 11. | Katz, T. J.; Acton, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 2738–2739. doi:10.1021/ja00789a084 |

| 38. | Sekiguchi, A.; Yatabe, T.; Kabuto, C.; Sakurai, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 5853–5854. doi:10.1021/ja00066a075 |

| 39. | Sekiguchi, A.; Kabuto, C.; Sakurai, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1989, 28, 55–56. doi:10.1002/ange.19891010133 |

| 24. | Woodward, R. B.; Fununaga, T.; Kelly, R. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3162–3164. doi:10.1021/ja01069a046 |

| 21. | Eaton, P. E.; Or, Y. S.; Branka, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 2134–2136. doi:10.1021/ja00398a062 |

| 22. | Eaton, P. E.; Or, Y. S.; Branka, S. J.; Ravi Shankar, B. K. Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 1621–1631. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87579-7 |

| 52. | Lipscomb, W. N.; Massa, L. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 2297–2299. doi:10.1021/ic00038a002 |

| 53. | Derecskei-Kovacs, A.; Dunlap, B. I.; Lipscomb, W. N.; Lowrey, A.; Marynick, D. S.; Massa, L. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 5617–5619. doi:10.1021/ic00103a004 |

| 23. | Scott, L. T.; Boorum, M. M.; McMahon, B. J.; Hagen, S.; Mack, J.; Blank, J.; Wegner, H.; de Meijere, A. Science 2002, 295, 1500–1503. doi:10.1126/science.1068427 |

| 54. | Gindulyte, A.; Lipscomb, W. N.; Massa, L. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 6544–6545. doi:10.1021/ic980559o |

| 55. | Bicerano, J.; Marynick, D. S.; Lipscomb, W. N. Inorg. Chem. 1978, 17, 3443–3453. doi:10.1021/ic50190a028 |

| 31. | Paquette, L. A.; Balogh, D. W.; Usha, R.; Kountz, D.; Christoph, G. G. Science 1981, 211, 575–576. doi:10.1126/science.211.4482.575 |

| 32. | Paquette, L. A.; Balogh, D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 774–783. doi:10.1021/ja00367a021 |

| 33. | Prinzbach, H.; Weber, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 33, 2239–2257. doi:10.1002/ange.19941062204 |

| 29. | Sobczak, R. L.; Osborn, M. E.; Paquette, L. A. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 4886–4890. doi:10.1021/jo00394a030 |

| 61. | Housecroft, C. E. Cluster molecules of the p-block elements; Oxford University Press: Oxford, U.K., 1994. |

| 62. | Corbett, J. D. In Structure and Bonding; Mingos, D. M. P., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1997; Vol. 87, pp 157–193. |

| 63. | Teo, B. K. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 1251–1257. doi:10.1021/ic00177a017 |

| 64. | Teo, B. K.; Longoni, G.; Chung, F. R. K. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 1257–1266. doi:10.1021/ic00177a018 |

| 27. | Codding, P. W.; Kerr, K. A.; Oudeman, A.; Sorensen, T. S. J. Organomet. Chem. 1982, 232, 193–199. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)89062-2 |

| 59. | Ciani, G.; D’Alfonso, G.; Freni, M.; Romiti, P.; Sironi, A. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1982, 705–706. doi:10.1039/C39820000705 |

| 28. | Eaton, P. E.; Bunnelle, W. H.; Engel, P. Can. J. Chem. 1984, 62, 2612–2626. doi:10.1139/v84-444 |

| 60. | Tian, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, B.; King, R. B. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 411–414. doi:10.1021/jp066272r |

| 25. | Jacobson, I. T. Acta Chem. Scand. 1967, 21, 2235–2246. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.21-2235 |

| 56. | Lee, C.-H.; Liang, S.; Haumann, T.; Boese, R.; de Meijere, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 559–561. doi:10.1002/ange.19931050428 |

| 26. | Paquette, L. A.; Wyvratt, M. J.; Berk, H. C.; Moerck, R. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 5845–5855. doi:10.1021/ja00486a042 |

| 57. | Muetterties, E. L.; Wiersma, R. J.; Hawthorne, M. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 7520–7522. doi:10.1021/ja00803a060 |

| 58. | Muetterties, E. L.; Hoel, E. L.; Salentine, C. G.; Hawthorne, M. F. Inorg. Chem. 1975, 14, 950–951. doi:10.1021/ic50146a050 |

© 2011 McGlinchey and Hopf; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)