Abstract

Background: Localized singlet diradicals are in general quite short-lived intermediates in processes involving homolytic bond-cleavage and formation reactions. In the past decade, long-lived singlet diradicals have been reported in cyclic systems such as cyclobutane-1,3-diyls and cyclopentane-1,3-diyls. Experimental investigation of the chemistry of singlet diradicals has become possible. The present study explores the substituents and the effect of their substitution pattern at the C(1)–C(3) positions on the lifetime of singlet octahydropentalene-1,3-diyls to understand the role of the substituents on the reactivity of the localized singlet diradicals.

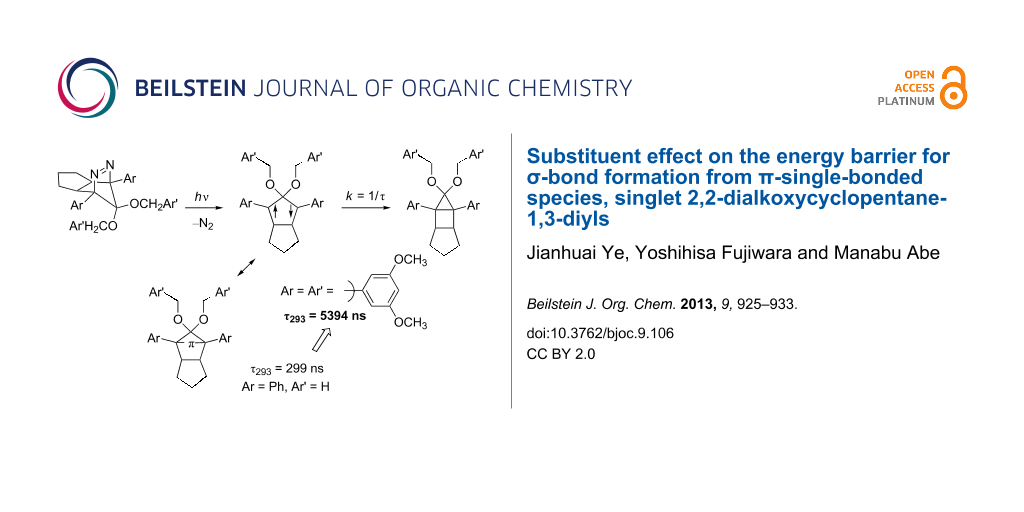

Results: A series of singlet 2,2-dialkoxy-1,3-diaryloctahydropentalene-1,3-diyls DR were generated in the photochemical denitrogenation of the corresponding azoalkanes AZ. The ring-closed products CP, i.e., 3,3-dialkoxy-2,4-diphenyltricyclo[3.3.0.02,4]octanes, were quantitatively obtained in the denitrogenation reaction. The first-order decay process (k = 1/τ) was observed for the fate of the singlet diradicals DR (λmax ≈ 580–590 nm). The activation parameters, ΔH‡ and ΔS‡, for the ring-closing reaction (σ-bond formation process) were determined by the temperature-dependent change of the lifetime. The energy barrier was found to be largely dependent upon the substituents Ar and Ar’. The singlet diradical DRf (Ar = 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl, OCH2Ar’ = OCH2(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)) was the longest-lived, τ293 = 5394 ± 59 ns, among the diradicals studied here. The lifetime of the parent diradical DR (Ar = Ph, OCH2Ar’ = OCH3) was 299 ± 2 ns at 293 K.

Conclusion: The lifetimes of the singlet 1,3-diyls are found to be largely dependent on the substituent pattern of Ar and Ar’ at the C(1)–C(3) positions. Both the enthalpy and entropy effect were found to play crucial roles in increasing the lifetime.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Localized singlet diradicals are key intermediates in processes involving the homolytic bond-cleavage and formation reactions (Figure 1) [1,2]. The singlet diradicals are, in general, quite short-lived species due to the very fast radical–radical coupling reaction [3]. However, in the past decade, the singlet diradicals have been observed or even isolated in cyclic systems such as cyclobutane-1,3-diyls [4-20] and cyclopentane-1,3-diyls [17,21-26]. Detailed experimental study of singlet diradical chemistry is thus now possible using the long-lived localized singlet diradicals.

So far, we have studied singlet diradical chemistry using long-lived 2,2-dialkoxy-1,3-diphenyloctahydropentalene-1,3-diyls DR with a singlet ground state, which can be cleanly generated by the photochemical denitrogenation of the corresponding azoalkanes AZ (Scheme 1). The 2,2-electron-withdrawing-group-substituted singlet 1,3-diradicals are categorized as Type-1 diradicals [1,27], which possess a π-single-bonding character (–π–, closed-shell character) between the two radical sites. The role of the alkoxy group (OR) on the lifetime (k = 1/τ) was investigated by combined studies of experiments and quantum chemical calculations [26,28]. The steric repulsion between the alkoxy group and the phenyl ring, which is indicated in the transition-state structure for the ring-closing reaction (Scheme 1), was found to play an important role in determining the energy barrier of the ring-closing process, τ293 = 292 ns (DRa: OR = OCH3, λmax = 574 nm) and 2146 ns (DRb: OR = OC10H21, λmax = 572 nm) [26]. The study prompted us to further investigate the kinetic stabilization of the singlet diradical species.

Scheme 1: Alkoxy group effect on the lifetime of π-single-bonded species DR.

Scheme 1: Alkoxy group effect on the lifetime of π-single-bonded species DR.

In the present study, the effect of the bulky 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl group substituent was investigated on the lifetime of the localized singlet diradicals. Thus, the aryl substituent was introduced at C(1), C(2), or/and C(3) positions of the diradicals DRd–g, and the substituent effects on the lifetime of the singlet diradicals were compared with the lifetime of a phenyl-group-substituted diradical DRc and the parent diradical DRa. The laser flash photolysis technique was used for the generation of DRc–g from the corresponding azoalkanes AZc–g (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Generation of singlet diradicals DRc–g and their reactivity in the photochemical denitrogenation of AZc–g.

Scheme 2: Generation of singlet diradicals DRc–g and their reactivity in the photochemical denitrogenation of ...

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of AZc–g and their steady-state photolyses. The precursor azoalkanes AZc–g were prepared in an analogous method to the synthesis of AZa,b [28] (Scheme 3). Pyrazoles 3c–f were synthesized in the reaction of tetrazines 1 (Ar = Ph or 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl) with 2,2-dialkoxy-5,5-dimethyl-Δ3-1,3,4-oxadiazolines 2 [29], which are the precursor of the dialkoxycarbene (Scheme 3a). Azoalkanes AZc–f (λmax ≈ 360 nm with ε ≈ 100) were obtained by a cycloaddition reaction with cyclopentadienes, and followed by a hydrogenation reaction [30,31]. The synthesis of AZg (Ar = 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl, Ar’ = H) was performed from the corresponding 1,3-diketone 4 (Scheme 3b). 2,2-Dimethoxy-1,3-diarylpropane-1,3-dione 5g was prepared from 1,3-dione 4 (R = 3,5-dimethoxybenzene) according to the method of Tiecco [32]. Pyrazole 3g was then synthesized by the reaction with hydrazine hydrate. AZg was obtained by the Diels–Alder [4 + 2]-cycloaddition with cyclopentadiene and hydrogenation using PtO2 as a catalyst. The endo-configured structure of azoalkanes AZc–g was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis as well as by NOE measurements.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of azoalkanes AZc–f and AZg.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of azoalkanes AZc–f and AZg.

The steady-state photolyses of AZc–g in benzene solution were performed with a Xenon lamp (500 W) through a Pyrex filter (hν > 300 nm). The ring-closed compounds CPc–g were quantitatively obtained in the denitrogenation reaction (Scheme 2). The quantum yields of the denitrogenation of AZc–g were determined to be ≈0.90 by comparison with those reported for similar azoalkanes [33]. The quantitative formation of CPc–g and the high quantum yield of the denitrogenation process suggest the clean generation of DRc–g in the photoirradiation reaction of AZc–g.

Detection of singlet diradicals DRc–g. The detection of singlet diradicals DRc–g was examined by the photochemical denitrogenation of azoalkanes AZc–g in a glassy matrix of 2-methyltetrahydrofurane (MTHF) at 80 K, [AZ] ≈ 4 × 10−3 mol/L, and by the laser flash photolysis experiments of AZc–g at room temperature in benzene solution. First of all, the MTHF matrix solution of AZ was irradiated with a 500 W Xenon lamp through a monochromator (λirr = 360 ± 10 nm). A strong absorption band, which corresponds to DRc–g, was observed in the visible region at 80 K (570–590 nm, Table 1), as exemplified for the photoirradiation of AZe in Figure 2a. The strong absorption bands are quite similar to those of singlet diradicals DRa,b with λmax = 574 nm and 572 nm [1,28], respectively. The assignment of the strong band to the singlet diradical is further supported by the following facts: (a) The absorptions obtained on photolysis in a MTHF glass were thermally persistent at 80 K and resembled that of the transient absorption spectra in solution (for example, DRe, λmax = 590 nm, Figure 2b); (b) the species were ESR-silent in the MTHF-matrix at 80 K; (c) the lifetime of the transient was insensitive to the presence of molecular oxygen (decay trace at 580 nm, Figure 2c); and (d) the activation parameters (Table 1) are similar to those for the decay process of DRa, in particular, the high (ca. 1012 s−1) pre-exponential Arrhenius factors (logA) are indicative of a spin-allowed reaction to the ring-closed products CPc–g [34].

![[1860-5397-9-106-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-9-106-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: (a) Absorption spectrum of the singlet diradical DRe in a MTHF matrix at 80 K; (b) transient absorption spectrum of AZe measured immediately after the laser pulse (λexc = 355 nm); (c) transient decay trace at 580 nm and 20 °C.

Figure 2: (a) Absorption spectrum of the singlet diradical DRe in a MTHF matrix at 80 K; (b) transient absorp...

Lifetime of singlet diradicals DRc–g and activation parameters for the ring-closing reaction. The decay traces of the intermediary singlet diradicals DRc–g at 293–333 K were measured in a benzene solution by the laser flash photolysis technique (λexc = 355 nm). The lifetime (τ = 1/k) was determined by the first-order decay rate constants (k) of DRc–g at 580 nm, e.g., Figure 2c for DRe. As shown in Table 1, the lifetime of the singlet diradical was largely dependent on the substituents Ar and Ar’. The activation parameters, ΔH‡, ΔS‡, Ea, logA, were determined from the Eyring plots and Arrhenius plots, which were obtained from the temperature-dependent change of the lifetime (Table 1). For comparison, the lifetime of diradical DRa (Table 1, entry 1) was also measured under similar conditions, and determined to be 299 ns at 293 K. The obtained lifetime was nearly the same as that obtained previously by us (292 ns) [28].

Table 1: Lifetimes and activation parameters of singlet diradicals DR.

| entry | DR | τ293K /nsa |

λmax

/nmb (at 80 K) |

ΔG‡293Kc

/kJ mol−1 |

ΔH‡c

/kJ mol−1 |

ΔS‡c

/J mol−1 K−1 |

Eac

/kJ mol−1 |

log Ac |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DRa | 299 | 573 | 35.1 ± 0.7 | 32.7 ± 0.2 | –8.1 ± 1.2 | 35.3 ± 0.2 | 12.8 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | DRc | 1305 | 583 | 39.1 ± 0.9 | 33.5 ± 0.6 | –17.9 ± 1.7 | 36.2 ± 0.6 | 12.3 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | DRd | 1933 | 584 | 39.6 ± 0.6 | 36.6 ± 0.1 | –10.1 ± 1.1 | 39.2 ± 0.1 | 12.7 ± 0.1 |

| 4 | DRe | 4001 | 592 | 40.9 ± 0.8 | 33.3 ± 0.4 | –27.8 ± 1.3 | 35.9 ± 0.4 | 11.8 ± 0.1 |

| 5 | DRf | 5394 | 593 | 42.2 ± 0.7 | 36.5 ± 0.3 | –19.4 ± 1.0 | 39.1 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 0.1 |

| 6 | DRg | 580 | 583 | 36.7 ± 0.4 | 33.0 ± 0.2 | –12.9 ± 1.0 | 35.6 ± 0.2 | 12.2 ± 0.1 |

aExperimental errors are ca. 5%.

bIn MTHF at 80 K.

cActivation parameters were determined by measurements of the lifetime of the singlet diradicals at five different temperatures in a temperature range from 293 to 333 K.

The lifetime of DRc (Ar = Ar’ = Ph) was found to be 1305 ns at 293 K (Table 1, entry 2), which was ca. 4.5 times longer than the parent DRa. On introduction of a 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl ring at C(2) position of the 1,3-diradical, i.e., DRd (Ar = Ph, Ar’ = 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl), a further increase of the lifetime at 293 K was observed to be 1933 ns (Table 1, entry 3). The result clearly indicates that the steric bulkiness plays an important role in increasing the energy barrier for the ring-closing reaction. Indeed, the activation enthalpy (ΔH‡ = 36.6 kJ mol−1, Table 1, entry 3) for DRd was found to be higher than that for DRa (ΔH‡ = 32.7 kJ mol−1, Table 1, entry 1). Interestingly, the effect of an aryl group substituent at C(1) and C(3) positions on the lifetime was found to be larger than that at C(2); compare the lifetime of DRe (4001 ns, Ar = 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl, Ar’ = Ph, Table 1, entry 4) with that of DRd (1933 ns, Table 1, entry 3). When the 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl group was introduced at all of the C(1), C(2), and C(3) positions, the lifetime of the diradical DRf (ΔG‡ = 42.2 kJ mol−1, Table 1, entry 5) was dramatically increased to 5394 ns at 293 K. The activation entropy (ΔS‡ = −27.8 and −19.4 J mol−1, Table 1, entries 4 and 5) also plays an important role in increasing the lifetime of the singlet species. A much shorter lifetime was found for the diradical DRg (Ar = 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl, Ar’ = H). Thus, the introduction of the bulky substituents is needed at all positions C(1)–C(3) of the 1,3-diradicals to increase the lifetime. The repulsive steric interactions of the Ar group with the Ar’ group are suggested to play important roles in increasing the energy barrier of the reaction from the diradicals to the ring-closed compounds CP. The results clearly indicate that the substituent effect using the sterically bulky group is effective to prolong the lifetime of the singlet diradicals.

Conclusion

We have succeeded in generating long-lived singlet diradical species DRc–g, τ293 = 580–5394 ns, which were much longer-lived species than DRa (τ293 = 299 ns). It was found that the lifetimes are largely dependent on the substituent pattern of Ar and Ar’ at the C(1)–C(3) positions of the 1,3-diyls. Thus, both the enthalpy and entropy effect were found to play crucial roles in increasing the lifetime.

Experimental

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and were used without additional purification, unless otherwise mentioned. Azoalkanes AZc–g were prepared according to the methods described previously (Scheme 3) and were isolated by silica gel column chromatography and GPC column chromatography. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were reported in parts per million (δ) by using CDCl3 or C6D6 as internal standards. Assignments of 13C NMR were carried out by DEPT measurements. IR spectra were recorded with a FTIR spectrometer. UV–vis spectra were taken by a JASCO V-630 spectrophotometer. Mass-spectrometric data were measured by a Mass Spectrometric Thermo Fisher Scientific LTQ Orbitrap XL, performed by the Natural Science Center for Basic Research and Development (NBARD), Hiroshima University.

Preparation of diazenes AZc–g

3,6-Diaryl-1,2,4,5-tetrazine 1. 3,6-Diphenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazine was purchased and directly used. The preparation of 3,6-(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-1,2,4,5-tetrazine (Ar = 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl) is as follows: In a 50 mL round-bottom flask, benzonitrile (3.7 g, 22.7 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL of absolute ethanol. Hydrazine (3.6 mL, 90 mmol) and sulfur (0.43 g, 13.5 mmol) were quickly added, and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then heated under reflux for 3 h. The remaining orange cake was solidified further in an ice bath. The solid was vacuum filtered, and washed with cold ethanol (3 × 10 mL) giving the crude dihydrotetrazine. The crude orange solid was then placed in a 50 mL beaker and dissolved in 20% acetic acid (15 mL) and 10 mL ether at room temperature with stirring. An aqueous solution of 10% NaNO2 (20 mL) was added to the solution in an ice bath. The immediate purple cloudiness signifies the completion of the reaction, as well as the evolution of brown nitric oxide gas. Vacuum filtration and washing with hot methanol (3 × 10 mL) gave the tetrazine as a red solid (3.07 g, 81%). mp: 248–250 °C; IR (neat, cm−1): 3022, 2981, 2947, 1611, 1462, 1393, 1221, 1067, 944, 843, 683; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.88 (s, 6H), 6.60 (t, J = 2.23 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 2.23 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 55.68 (q, OCH3), 105.48 (d, CH), 105.90 (d, CH), 133.44 (s, C), 161.54 (s, COCH3); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C18H20O4N4, 379.13768; found, 379.13776.

5,5-Dimethyl-2,2-bis(3,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-Δ3-1,3,4-oxadiazoline (2f). A solution of (3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxycarbonyl)hydrazone of acetone (1.30 g, 4.87 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of Pb(OAc)4 (2.59 g, 5.84 mmol) under nitrogen. The reaction mixture was stirred in an ice bath for 2 h, and then at room temperature for 24 h. After the stirring, the solid was filtered over Celite and the organic layer was washed with 10% aq NaHCO3. The mixture was filtered again until no precipitate was deposited. The organic phase was concentrated under reduced pressure. The corresponding 3,5-dimethoxybenzyl alcohol (2.46 g, 14.6 mmol) and TFA (0.04 mL, 0.49 mmol) were then added to the organic mixture. The solution was heated to 40 °C and stirred for 24 h before KOH pellets were added, and stirring was continued for another 3 h. After extracting with CH2Cl2, washing with brine, and drying by MgSO4, the organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure. The product was purified by column chromatography (eluent: EtOAc/hexane = 30/70, Rf = 0.17) to give the product as a yellow liquid (0.48 g, 23%). IR (neat, cm−1): 3006, 2959, 2843, 1750, 1622, 1480, 1386, 1236, 1076, 925, 846, 687; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.49 (s, 6H), 3.67 (s, 12H), 4.66 (q, J = 11.8 Hz, 36.78 Hz, 4H), 6.29 (t, J = 2.21 Hz, 2H), 6.41 (d, J = 2.21 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.12 (q, CH3), 55.29 (q, OCH3), 66.72 (t, CH2), 99.94 (d, CH, Ar ring), 105.50 (d, CH, Ar ring), 119.63 (s, C(CH3)2), 136.71 (s, C), 138.97 (s, C(OCH2Ar)2), 160.83 (s, COCH3); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C22H28O7N2Na, 455.17887; found, 455.17899.

1,3-Bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propane-1,3-dione (4). 3,5-dimethoxyacetophenone (2.1 g, 11.7 mmol), 3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid (2.75 g, 14.04 mmol), and NaH (0.94 g, 23.4 mmol) was dissolved in THF (20 mL) under N2 atmosphere in a 50 mL flask. The mixture was heated under reflux (75 °C) for 14 h under a N2 atmosphere, then cooled down to room temperature. The mixture was slowly added to cold HCl. The organic layer was extracted with ether, washed with brine, and dried with anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was removed by vacuum evaporator. The dry solid was then recrystallized in methanol to give the compound as a yellow crystal (2.77 g, 69%). mp: 132 °C; IR (neat, cm−1): 3140, 3000, 2943, 1562, 1466, 1351, 1298, 1158, 1053, 842, 668; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.78 (s, 12H), 6.56 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 6.65 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 55.56 (q, OCH3), 93.56 (t, CH2), 104.62 (d, CH), 105.05 (d, CH), 137.52 (s, C), 160.92 (s, COCH3), 185.47 (s, OC=O); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C19H20O6Na, 367.11521; found, 367.11456.

1,3-Bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2,2-dimethoxypropane-1,3-dione (5). 1,3-Dione 4 (2.76 g, 8 mmol) and diphenyl diselenide (1.25 g, 4 mmol) were dissolved in methanol (50 mL), and ammonium persulfate (3.65 g, 16 mmol) was added to the mixture. The solution was heated under reflux for 4 h with stirring under nitrogen. Then the mixture was cooled to room temperature, and slowly added to ice water. The organic compound was extracted by chloroform and purified by silica-gel column chromatography (eluent: EtOAc/hexane = 30/70, Rf = 0.30) to give the product as a yellow liquid (2.9 g, 90%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.41 (s, 6H), 3.77 (s, 12H), 6.59 (t, J = 2.44 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 2.44 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 50.97 (q, C(OCH3)2), 55.53 (q, OCH3), 103.89 (s, C), 107.22 (d, CH), 107.34 (d, CH), 135.50 (s, C), 160.66 (s, COCH3), 192.47 (s, C=O); IR (neat, cm−1): 3027, 2965, 2845, 1691, 1605, 1466, 1429, 1321, 1162, 1070, 1036, 863, 671; ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C21H24O8Na, 427.13634; found, 427.13602.

4,4-diaryloxy-3,5-diarylpyrazole (3c–f)

General Procedure. Oxadiazoline (1 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (2 mL) in a sealed tube. The mixture was stirred with tetrazine (1.10 mmol) in a sealed tube for 24 h at 120 °C under nitrogen. After filtration, the crude was purified by column chromatograph (in ca. 40% yield).

4,4-Dibenzyloxy-3,5-diphenylpyrazole (3c). Yellow powder (from MeOH), mp: 150–151 °C; IR (neat, cm−1): 3070, 3066, 2948, 2881, 1585, 1557, 1498, 1447, 1391, 1382, 1111, 970, 916, 856, 694; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.21 (s, 4H), 7.04–7.06 (m, 4H), 7.19–7.20 (m, 6H), 7.50–7.57 (m, 6H), 8.38–8.39 (m, 4 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 66.73 (t, CH2), 115.96 (s, C), 127.74 (d, CH, benzyloxy), 127.95 (d, CH, benzyloxy), 128.13 (d, CH, phenyl), 128.18 (d, CH, benzyloxy), 128.26 (d, CH, phenyl), 129.03 (d, CH, phenyl), 132.47 (s, C, phenyl), 135.45 (s, C, benzyloxy), 167.09 (s, C); HRMS–EI calcd for C29H24N2O2, 432.1838; found, 432.1842; Rf = 0.40 (EtOAc/hexane = 30/70).

4,4-Bis(3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-3,5-diphenylpyrazole (3d). Yellow powder (from MeOH), mp: 140–141 °C; IR (neat, cm−1): 3024, 2951, 2845, 1603, 1475, 1456, 1388, 1160, 1118, 1102, 851; 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 3.19 (s, 12H), 4.21 (s, 4H), 6.28 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 4H), 6.42 (t, J = 2.36 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.15 Hz, 6H, phenyl), 8.68 (m, 4H, phenyl); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 55.76 (q, OCH3), 67.11 (t, CH2), 100.99 (d, CH, aryl), 106.15 (d, CH, aryl), 116.69 (s, C), 128.35 (d, CH, phenyl), 128.77 (s, C), 129.24 (d, CH, phenyl), 132.30 (d, CH, phenyl), 138.40 (s, C), 161.30 (s, C), 167.29 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C33H32O6N2Na, 575.21526; found, 575.21387; Rf = 0.27 (EtOAc/hexane = 30/70).

4,4-Dibenzyloxy-3,5-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)pyrazole (3e). Yellow powder (from MeOH), mp: 183–184 °C; IR (neat, cm−1): 3025, 2952, 2847, 1605, 1551, 1456, 1426, 1371, 1160, 1117, 849, 670; 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 3.33 (s, 12H), 4.31 (s, 2H), 6.78 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 6.93–7.01 (m, 10H), 8.02 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 55.06 (q, OCH3), 67.02 (t, CH2), 105.54 (d, CH, aryl), 106.52 (d, CH, aryl), 116.22 (s, C), 128.59 (d, CH, phenyl), 128.45 (d, CH, phenyl), 128.19 (d, CH, phenyl), 130.47 (s, C, aryl), 136.24 (s, C, phenyl), 161.81 (s, COCH3), 167.53 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C33H33N6O2, 553.23331; found, 553.23267; Rf = 0.13 (EtOAc/hexane = 20/80).

4,4-Bis(3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-3,5-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)pyrazole (3f). IR (neat, cm−1): 3010, 2942, 1605, 1552, 1441, 1371, 1140, 1120, 849; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.24 (s, 12H), 3.34 (s, 12H), 4.36 (s, 6H), 6.38 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 4H), 6.43 (t, J = 2.36 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 8.04 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 54.74 (q, OCH3), 55.03 (q, OCH3), 67.19 (t, CH2), 101.16 (d, CH), 105.71 (d, CH), 106.08 (d, CH), 106.28 (d, CH), 116.36 (s, C), 130.46 (s, C), 138.47 (s, C), 161.33 (s, COCH3), 161.77 (s, COCH3), 167.58 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C37H40O10N2Na, 695.25752; found, 695.25775; Rf = 0.17 (EtOAc/hexane = 30/70).

4,4-Dimethoxy-3,5-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)pyrazole (3g). To a solution of 1,3-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2,2-dimethoxypropane-1,3-dione (2.8 g, 6.92 mmol) in chloroform (10 mL) was added dropwise NH2NH2·H2O (0.40 mL, 8.30 mmol). The mixture was heated under reflux and kept under stirring for 6 h. The reaction was quenched with HCl. A solution of 10% NaHCO3 was added to the mixture. After extraction with chloroform, the organic phase was washed with brine, dried with Na2SO4, concentrated and then purified by column chromatography to give 3g in 89.6% yield. mp: 179–180 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.04 (s, 6H), 3.83 (s, 12H), 6.62 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 51.93 (q, CH3), 55.52 (q, OCH3), 105.21 (d, CH,), 105.27 (d, CH), 116.91 (s, C), 129.23 (s, C), 161.00 (s, COCH3), 166.84 (s, C); IR (neat, cm−1): 3012, 2951, 1597, 1548, 1427, 1375, 1158, 1125, 1062, 980, 844; ESIMS (m/z): calcd for C21H25N6O2, 401.17071; found, 401.17041; Rf = 0.10 (EtOAc/hexane = 20/80).

endo-2,3-Diazo-10,10-diaryloxy-1,4-diaryltricyclo[5.2.1.05,9]dec-2-ene (AZc–g)

General procedure. To a solution of cyclopentadiene (1 mL) and pyrazole (2 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was added dropwise trifluoroacetic acid (1 mmol) in an ice bath under nitrogen. The reaction was traced by TLC analysis. After stirring for about 15 min, the reaction was quenched with 10% aq NaHCO3 until the pH of the solution reached 8. After washing with water and brine, the organic phase was dried with MgSO4, then filtered and concentrated. The [4 + 2] cycloadduct was dissolved in benzene (2 mL), and 5 mg of PtO2 was added as a catalyst. The mixture was stirred under a hydrogen atmosphere for 24 h at room temperature. After stirring, the catalyst was removed by filtration over Celite, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The product was purified by column chromatograph to give the product as colorless liquid (ca. 60%). The endo configuration was determined by NOE measurements.

endo-2,3-Diazo-10,10-dibenzyloxy-1,4-diphenyltricyclo[5.2.1.05,9]dec-2-ene (AZc). IR (neat, cm−1): 3037, 2968, 2886, 1739, 1607, 1498, 1456, 1387, 1139, 1085, 1029, 702; UV (MTHF) λmax 365 (ε 106.7); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 1.20–1.75 (m, 6H), 3.69 (t, J = 5.13 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (s, 2H), 4.29 (s, 2H), 6.90–8.19 (m, 20H, overlapping with C6H6); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 25.96 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.16 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 49.27 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 66.16 (t, COCH2), 66.34 (t, OCH2), 94.83 (s, C), 119.57 (s, C), 126.66 (d, CH), 126.87 (d, CH), 127.33 (d, CH), 128.61 (d, CH), 128.71 (d, CH), 129.01 (d, CH), 137.22 (s, C), 138.13 (s, C), 138.19 (s, C); HRMS–EI (m/z): calcd for C34H32O2N2, 500.6301; found, 500.2462. Rf = 0.57 (EtOAc/hexane = 20/80).

endo-2,3-Diazo-10,10-bis(3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-1,4-diphenyltricyclo[5.2.1.05,9]dec-2-ene (AZd). IR (neat, cm−1): 3022, 2966, 2844, 1751, 1603, 1473, 1326, 1162, 1072, 930, 844, 703; UV (MTHF) λmax 364 (ε 175.1); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.25–1.66 (m, 6H), 3.68 (s, 6H), 3.70 (t, J = 5.33 Hz, 2H), 3.75 (s, 6H), 3.89 (s, 2H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 6.07 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 2H), 6.24 (t, J = 2.36 Hz, 1H), 6.30 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 2H), 6.36 (t, J = 2.36 Hz, 1H), 7.40–8.03 (m, 10H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 26.21 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.34 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 49.42 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 55.69 (q, OCH3), 55.74 (q, OCH3), 66.17 (t, COCH2), 95.15 (s, C), 99.80 (d, CH), 100.00 (d, CH), 104.26 (d, CH), 105.04 (d, CH), 119.54 (s, C), 128.55 (d, CH), 128.92 (d, CH), 128.96 (d, CH), 136.67 (s, C), 140.41 (s, C), 140.67 (s, C), 161.00 (s, C) , 161.28 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C38H41O6N2, 621.29591; found, 621.29449; Rf = 0.27 (EtOAc/hexane = 20/80).

endo-2,3-diazo-1,4-bis(3’,5’-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-10,10-dibenzyloxytricyclo[5.2.1.05,9]dec-2-ene (AZe). IR (neat, cm−1): 3014, 2972, 1600, 1461, 1450, 1357, 1157, 1069, 973, 856; UV (MTHF) λmax 365 (ε 184.2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 1.20–1.83 (m, 6H), 3.41 (s, 12H), 3.57 (t, J = 4.47 Hz, 2H), 4.31 (s, 2H), 4.46 (s, 2H), 6.68 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H), 7.02–7.57 (m, 10H, overlapping with C6D6); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 26.13 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.19 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 49.50 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 54.91 (q, OCH3), 66.04 (t, COCH2), 66.32 (t, COCH2), 94.96 (s, C), 101.03 (d, CH), 107.11 (d, CH), 119.74 (s, C), 127.00 (d, CH), 127.16 (d, CH), 127.38 (d, CH), 127.72 (d, CH), 128.54 (d, CH), 128.60 (d, CH), 138.19 (s, C), 138.24 (s, C), 139.58 (s, C), 161.62 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C38H40O6N2Na, 643.27786; found, 643.27802.

endo-2,3-Diazo-1,4-bis(3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-10,10-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenoxy)tricyclo[5.2.1.05,9]dec-2-ene (AZf). IR (neat, cm−1): 3009, 2965, 2842, 1606, 1467, 1430, 1352, 1160, 1070, 1057, 943, 840; UV (MTHF) λmax 365 (ε 249.6); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 1.20–1.80 (m, 6H), 3.23 (s, 6H), 3.32 (s, 6H), 3.44 (s, 12H), 3.60 (t, J = 5.37 Hz, 2H), 4.38 (s, 2H), 4.56 (s, 2H), 6.33 (d, J = 2.29 Hz, 2H), 6.40 (t, J = 2.29 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (t, J = 2.29 Hz, 1H) 6.54 (d, J = 2.29 Hz, 2H), 6.64 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 26.11 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.16 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 49.52 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 54.69 (q, OCH3), 54.81 (q, OCH3), 54.91 (2×q, OCH3), 65.93 (t, COCH2), 66.32 (t, COCH2), 95.11 (s, C), 100.08 (d, CH), 100.32 (d, CH), 100.92 (2×d, CH), 104.62 (s, C), 104.70 (s, C), 107.23 (2×s, C), 119.91 (s, C), 139.46 (2×s, C), 140.66 (s, C), 140.77 (s, C), 161.33 (2×s, C), 161.58 (s, C), 161.62 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C42H48O10N2Na, 763.32012; found,763.32043.

endo-2,3-Diazo-1,4-bis(3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-10,10-dimethoxytricyclo[5.2.1.05,9]dec-2-ene (AZg). IR (neat, cm−1): 2973, 2846, 1602, 1464, 1359, 1158, 1088, 1022, 942, 848; UV (MTHF) λmax 364 (ε 169.9); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 0.9–1.75 (m, 6H), 2.69 (s, 3H), 2.80 (s, 3H), 3.36 (t, J = 5.49 Hz, 2H), 3.42 (s, 12H), 6.64 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 26.08 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.16 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 49.29 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 51.46 (q, OCH3), 51.75 (q, OCH3), 51.92 (2×q, OCH3), 94.65 (s, C), 100.30 (d, CH), 107.33 (d, CH), 119.76 (s, C), 139.86 (s, C), 161.52 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C26H32O6N2Na, 491.21526; found, 491.21466.

General procedure for photolysis. A sample (30.0 mg) of the diazenes AZ was dissolved in 1.0 mL of C6D6. The photolysis was performed with a 500 W Xenon-lamp through a Pyrex filter (hν > 300 nm) at room temperature (ca. 20 °C). The photolysate was directly analyzed by NMR spectroscopy (1H: 500 MHz, 13C: 125 MHz), which indicated the quantitative formation of the housanes CP. The housanes CPc–g were isolated by using silica-gel column chromatography. The spectroscopic data are as follows:

3,3-Dibenzyloxy-2,4-diphenyltricyclo[3.3.0.02,4]octane (CPc). 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 1.41–1.93 (m, 6H), 3.19 (d, J = 6.34 Hz, 2H), 4.31 (s, 2H), 4.92 (s, 2H), 6.96–7.45 (m, 20H, overlapping with C6D6); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 25.28 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.38 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 41.73 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 48.05 (s, C), 67.16 (t, COCH2), 69.66 (t, OCH2), 98.43 (s, C), 126.57 (d, CH), 127.26 (d, CH), 127.40 (d, CH), 127.92 (d, CH), 128.12 (d, CH), 128.35 (d, CH), 128.46 (d, CH), 128.68 (d, CH), 130.54 (d, CH), 135.25 (s, C, phenyl), 138.59 (s, C, benzyloxy), 138.90 (s, C, benzyloxy); HRMS–EI (m/z): calcd for C34H32O2, 472.2402; found, 472.2424.

3,3-Bis(3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-2,4-diphenyltricyclo[3.3.0. 02,4]octane (CPd). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.40–1.92 (m, 6H), 3.12 (d, J = 6.29 Hz, 2H), 3.22 (s, 6H), 3.37 (s, 6H), 4.35 (s, 2H), 4.99 (s, 2H), 6.31 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 2H), 6.41 (t, J = 2.36 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 2H), 7.02–7.46 (m, 10H, overlapping with C6D6); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 25.22 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.34 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 41.68 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 48.18 (s, C), 54.68 (q, OCH3), 54.89 (q, OCH3), 67.07 (t, COCH2), 69.78 (t, COCH2), 98.46 (s, C), 100.04 (d, CH), 100.06 (d, CH), 104.91 (d, CH), 105.94 (d, CH), 126.48 (2×d, CH, phenyl), 128.04 (2×d, CH, phenyl), 130.51 (2×d, CH, phenyl), 135.22 (2×s, C, phenyl), 140.90 (s, C), 141.30 (s, C), 161.19 (s, COCH3), 161.64 (s, COCH); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C38H41O6Na, 615.27171; found, 615.27130.

3,3-Bisbenzyloxy-2,4-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)tricyclo[3.3.0.02,4]octane (CPe). 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 1.40–2.02 (m, 6H), 3.05 (d, J = 6.40 Hz, 2H), 3.29 (s, 12H), 4.41 (s, 2H), 4.90 (s, 2H), 6.43 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 6.80 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H), 6.86–7.34 (m, 10H, overlapping with C6D6); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 25.44 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.43 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 41.82 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 48.47 (s, C), 54.78 (q, OCH3), 67.44 (t, COCH2), 69.51 (t, COCH2), 98.39 (s, C), 99.22 (d, CH), 108.88 (d, CH), 127.19 (d, CH), 127.54 (d, CH), 127.80 (d, CH), 128.06 (d, CH), 128.18 (d, CH), 128.59 (d, CH), 137.30 (s, C), 138.50 (s, C, phenyl), 138.81 (s, C, phenyl), 160.97 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C38H40O6Na, 615.27171; found, 615.27167.

3,3-Bis(3,5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-2,4-bis(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)tricyclo[3.3.0.02,4]octane (CPf). 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 1.43–2.08 (m, 6H), 3.15 (d, J = 6.17 Hz, 2H), 3.30 (s, 6H), 3.35 (s, 12H), 3.38 (s, 6H), 4.51 (s, 2H), 5.01 (s, 2H), 6.34 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 2H), 6.41 (t, J = 2.36 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 6.54 (t, J = 2.36 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 2.36 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 25.46 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.44 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 41.80 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 48.64 (s, C), 54.67 (q, OCH3), 54.78 (q, OCH3), 54.89 (2×q, OCH3), 67.29 (t, COCH2), 69.76 (t, COCH2), 98.41 (s, C), 99.18 (2×d, CH), 100.12 (d, CH), 100.32 (d, CH), 104.93 (d, CH), 105.96 (d, CH), 108.89 (2×d, CH), 137.30 (2×s, C), 140.88 (s, C), 141.26 (s, C), 160.96 (2×s, COCH3), 161.187 (s, COCH3), 161.59 (s, COCH3); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C42H48O10Na, 735.31397; found,735.31415.

3,3-Dimethoxy-2,4-bis(3’,5’-dimethoxyphenyl)tricyclo[3.3.0.02,4]octane (CPg). 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 1.43–2.03 (m, 6H), 2.94 (s, 3H), 2.96 (d, J = 6.47 Hz, 2H), 3.37 (s, 12H), 3.48 (s, 3H), 6.51 (t, J = 2.28 Hz, 2H), 6.79 (d, J = 2.28 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ 25.49 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 28.45 (t, CH2, cyclopentane), 41.83 (d, CH, cyclopentane), 48.13 (s, C), 52.37 (q, OCH3), 54.01 (q, OCH3), 54.85 (2×q, OCH3), 98.61 (s, C), 99.05 (d, CH), 108.88 (d, CH), 137.59 (s, COCH3), 161.07 (s, C); ESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C26H32O6Na, 463.20911; found, 463.20844.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: NMR spectra of compounds 1–5, AZc–g, and CPc–g. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.5 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

NMR and MS measurements were performed at N-BARD, Hiroshima University. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Science Research on Innovative Areas “Stimuli-responsive Chemical Species” (No. 24109008), “pi-Space” (No. 21108516), and No. 19350021 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and by the Tokuyama Science Foundation.

References

-

Abe, M.; Ye, J.; Mishima, M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3808–3820. doi:10.1039/c2cs00005a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Abe, M. Chem. Rev. 2013, in press.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

De Feyter, S.; Diau, E. W.-G.; Zewail, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 260–263. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<260::AID-ANIE260>3.0.CO;2-R

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Niecke, E.; Fuchs, A.; Baumeister, F.; Nieger, M.; Schoeller, W. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 555–557. doi:10.1002/anie.199505551

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schoeller, W. W.; Niecke, E. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 2015–2023. doi:10.1039/c1cp23016f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scheschkewitz, D.; Amii, H.; Gornitzka, H.; Schoeller, W. W.; Bourissou, D.; Bertrand, G. Science 2002, 295, 1880–1881. doi:10.1126/science.1068167

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cui, C.; Brynda, M.; Olmstead, M. M.; Power, P. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 6510–6511. doi:10.1021/ja0492182

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Olmstead, M. M.; Fettinger, J. C.; Power, P. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14164–14165. doi:10.1021/ja906053y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cox, H.; Hitchcock, P. B.; Lappert, M. F.; Pierssens, L. J.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4500–4504. doi:10.1002/anie.200460039

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Beweries, T.; Kuzora, R.; Rosenthal, U.; Schulz, A.; Villinger, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8974–8978. doi:10.1002/anie.201103742

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takeuchi, K.; Ichinohe, M.; Sekiguchi, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12478–12481. doi:10.1021/ja2059846

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sugiyama, H.; Ito, S.; Yoshifuji, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 3802–3804. doi:10.1002/anie.200351727

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yoshifuji, M.; Hirano, Y.; Schnakenburg, G.; Streubel, R.; Niecke, E.; Ito, S. Helv. Chim. Acta 2012, 95, 1723–1729. doi:10.1002/hlca.201200442

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Henke, P.; Pankewitz, T.; Klopper, W.; Breher, F.; Schnöckel, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8141–8145. doi:10.1002/anie.200901754

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, J.; Ding, Y.; Hattori, K.; Inagaki, S. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 4245–4255. doi:10.1021/jo035687v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abe, M.; Ishihara, C.; Takegami, A. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 7250–7255. doi:10.1021/jo0490447

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abe, M.; Kubo, E.; Nozaki, K.; Matsuo, T.; Hayashi, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7828–7831. doi:10.1002/anie.200603287

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nakamura, T.; Gagliardi, L.; Abe, M. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2010, 23, 300–307. doi:10.1002/poc.1643

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nakamura, T.; Takegami, A.; Abe, M. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1956–1960. doi:10.1021/jo902714c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mondal, K. C.; Roesky, H. W.; Schwarzer, M. C.; Frenking, G.; Tkach, I.; Wolf, H.; Kratzert, D.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Niepötter, B.; Stalke, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1801–1805. doi:10.1002/anie.201204487

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, J. D.; Hrovat, D. A.; Borden, W. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 5425–5427. doi:10.1021/ja00091a054

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Adam, W.; Borden, W. T.; Burda, C.; Foster, H.; Heidenfelder, T.; Heubes, M.; Hrovat, D. A.; Kita, F.; Lewis, S. B.; Scheutzow, D.; Wirz, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 593–594. doi:10.1021/ja972977i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abe, M.; Adam, W.; Heidenfelder, T.; Nau, W. M.; Zhang, X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 2019–2026. doi:10.1021/ja992507j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abe, M.; Kubo, E.; Nozaki, K.; Matsuo, T.; Hayashi, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11924.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abe, M.; Furunaga, H.; Ma, D.; Gagliardi, L.; Bodwell, G. J. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 7612–7619. doi:10.1021/jo3016105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nakagaki, T.; Sakai, T.; Mizuta, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Abe, M. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, in press. doi:10.1002/chem.201300038

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Schoeller, W. W.; Rozhenko, A.; Bourissou, D.; Bertrand, G. Chem.–Eur. J. 2003, 9, 3611–3617. doi:10.1002/chem.200204508

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abe, M.; Adam, W.; Hara, M.; Hattori, M.; Majima, T.; Nojima, M.; Tachibana, K.; Tojo, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6540–6541. doi:10.1021/ja026301l

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Lu, X.; Reid, D. L.; Warkentin, J. Can. J. Chem. 2001, 79, 319–327.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Beck, K.; Hünig, S. Chem. Ber. 1987, 120, 477–483. doi:10.1002/cber.19871200406

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Adam, W.; Heidenfelder, T.; Sahin, C. Synthesis 1995, 1163–1170. doi:10.1055/s-1995-4072

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tiecco, M.; Testaferri, L.; Tingoli, M.; Bartoli, D.; Marini, F. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 5207–5210. doi:10.1021/jo00017a039

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Clark, W. D. K.; Steel, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 6347–6355. doi:10.1021/ja00753a001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Johnston, L. J.; Scaiano, J. C. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 521–547. doi:10.1021/cr00093a004

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Abe, M.; Ye, J.; Mishima, M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3808–3820. doi:10.1039/c2cs00005a |

| 2. | Abe, M. Chem. Rev. 2013, in press. |

| 1. | Abe, M.; Ye, J.; Mishima, M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3808–3820. doi:10.1039/c2cs00005a |

| 27. | Schoeller, W. W.; Rozhenko, A.; Bourissou, D.; Bertrand, G. Chem.–Eur. J. 2003, 9, 3611–3617. doi:10.1002/chem.200204508 |

| 28. | Abe, M.; Adam, W.; Hara, M.; Hattori, M.; Majima, T.; Nojima, M.; Tachibana, K.; Tojo, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6540–6541. doi:10.1021/ja026301l |

| 17. | Abe, M.; Kubo, E.; Nozaki, K.; Matsuo, T.; Hayashi, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7828–7831. doi:10.1002/anie.200603287 |

| 21. | Xu, J. D.; Hrovat, D. A.; Borden, W. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 5425–5427. doi:10.1021/ja00091a054 |

| 22. | Adam, W.; Borden, W. T.; Burda, C.; Foster, H.; Heidenfelder, T.; Heubes, M.; Hrovat, D. A.; Kita, F.; Lewis, S. B.; Scheutzow, D.; Wirz, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 593–594. doi:10.1021/ja972977i |

| 23. | Abe, M.; Adam, W.; Heidenfelder, T.; Nau, W. M.; Zhang, X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 2019–2026. doi:10.1021/ja992507j |

| 24. | Abe, M.; Kubo, E.; Nozaki, K.; Matsuo, T.; Hayashi, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11924. |

| 25. | Abe, M.; Furunaga, H.; Ma, D.; Gagliardi, L.; Bodwell, G. J. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 7612–7619. doi:10.1021/jo3016105 |

| 26. | Nakagaki, T.; Sakai, T.; Mizuta, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Abe, M. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, in press. doi:10.1002/chem.201300038 |

| 4. | Niecke, E.; Fuchs, A.; Baumeister, F.; Nieger, M.; Schoeller, W. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 555–557. doi:10.1002/anie.199505551 |

| 5. | Schoeller, W. W.; Niecke, E. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 2015–2023. doi:10.1039/c1cp23016f |

| 6. | Scheschkewitz, D.; Amii, H.; Gornitzka, H.; Schoeller, W. W.; Bourissou, D.; Bertrand, G. Science 2002, 295, 1880–1881. doi:10.1126/science.1068167 |

| 7. | Cui, C.; Brynda, M.; Olmstead, M. M.; Power, P. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 6510–6511. doi:10.1021/ja0492182 |

| 8. | Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Olmstead, M. M.; Fettinger, J. C.; Power, P. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14164–14165. doi:10.1021/ja906053y |

| 9. | Cox, H.; Hitchcock, P. B.; Lappert, M. F.; Pierssens, L. J.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4500–4504. doi:10.1002/anie.200460039 |

| 10. | Beweries, T.; Kuzora, R.; Rosenthal, U.; Schulz, A.; Villinger, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8974–8978. doi:10.1002/anie.201103742 |

| 11. | Takeuchi, K.; Ichinohe, M.; Sekiguchi, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12478–12481. doi:10.1021/ja2059846 |

| 12. | Sugiyama, H.; Ito, S.; Yoshifuji, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 3802–3804. doi:10.1002/anie.200351727 |

| 13. | Yoshifuji, M.; Hirano, Y.; Schnakenburg, G.; Streubel, R.; Niecke, E.; Ito, S. Helv. Chim. Acta 2012, 95, 1723–1729. doi:10.1002/hlca.201200442 |

| 14. | Henke, P.; Pankewitz, T.; Klopper, W.; Breher, F.; Schnöckel, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8141–8145. doi:10.1002/anie.200901754 |

| 15. | Ma, J.; Ding, Y.; Hattori, K.; Inagaki, S. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 4245–4255. doi:10.1021/jo035687v |

| 16. | Abe, M.; Ishihara, C.; Takegami, A. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 7250–7255. doi:10.1021/jo0490447 |

| 17. | Abe, M.; Kubo, E.; Nozaki, K.; Matsuo, T.; Hayashi, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7828–7831. doi:10.1002/anie.200603287 |

| 18. | Nakamura, T.; Gagliardi, L.; Abe, M. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2010, 23, 300–307. doi:10.1002/poc.1643 |

| 19. | Nakamura, T.; Takegami, A.; Abe, M. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1956–1960. doi:10.1021/jo902714c |

| 20. | Mondal, K. C.; Roesky, H. W.; Schwarzer, M. C.; Frenking, G.; Tkach, I.; Wolf, H.; Kratzert, D.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Niepötter, B.; Stalke, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1801–1805. doi:10.1002/anie.201204487 |

| 1. | Abe, M.; Ye, J.; Mishima, M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3808–3820. doi:10.1039/c2cs00005a |

| 28. | Abe, M.; Adam, W.; Hara, M.; Hattori, M.; Majima, T.; Nojima, M.; Tachibana, K.; Tojo, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6540–6541. doi:10.1021/ja026301l |

| 3. | De Feyter, S.; Diau, E. W.-G.; Zewail, A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 260–263. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<260::AID-ANIE260>3.0.CO;2-R |

| 34. | Johnston, L. J.; Scaiano, J. C. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 521–547. doi:10.1021/cr00093a004 |

| 32. | Tiecco, M.; Testaferri, L.; Tingoli, M.; Bartoli, D.; Marini, F. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 5207–5210. doi:10.1021/jo00017a039 |

| 28. | Abe, M.; Adam, W.; Hara, M.; Hattori, M.; Majima, T.; Nojima, M.; Tachibana, K.; Tojo, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6540–6541. doi:10.1021/ja026301l |

| 33. | Clark, W. D. K.; Steel, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 6347–6355. doi:10.1021/ja00753a001 |

| 26. | Nakagaki, T.; Sakai, T.; Mizuta, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Abe, M. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, in press. doi:10.1002/chem.201300038 |

| 26. | Nakagaki, T.; Sakai, T.; Mizuta, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Abe, M. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013, in press. doi:10.1002/chem.201300038 |

| 28. | Abe, M.; Adam, W.; Hara, M.; Hattori, M.; Majima, T.; Nojima, M.; Tachibana, K.; Tojo, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6540–6541. doi:10.1021/ja026301l |

| 30. | Beck, K.; Hünig, S. Chem. Ber. 1987, 120, 477–483. doi:10.1002/cber.19871200406 |

| 31. | Adam, W.; Heidenfelder, T.; Sahin, C. Synthesis 1995, 1163–1170. doi:10.1055/s-1995-4072 |

© 2013 Ye et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)