Abstract

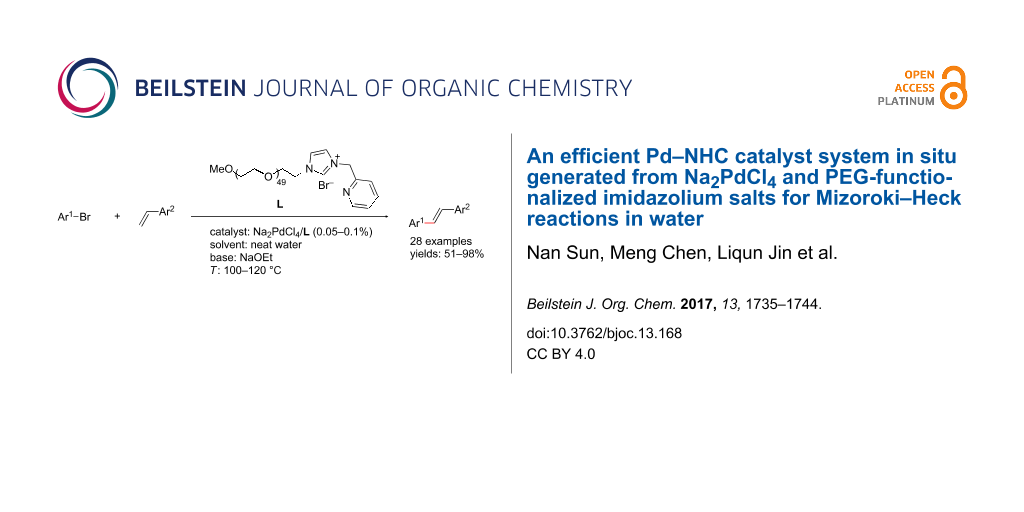

Three PEG-functionalized imidazolium salts L1–L3 were designed and prepared from commercially available materials via a simple method. Their corresponding water soluble Pd–NHC catalysts, in situ generated from the imidazolium salts L1–L3 and Na2PdCl4 in water, showed impressive catalytic activity for aqueous Mizoroki–Heck reactions. The kinetic study revealed that the Pd catalyst derived from the imidazolium salt L1, bearing a pyridine-2-methyl substituent at the N3 atom of the imidazole ring, showed the best catalytic activity. Under the optimal conditions, a wide range of substituted alkenes were achieved in good to excellent yields from various aryl bromides and alkenes with the catalyst TON of up to 10,000.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Nowadays, both increasing environmental concerns and drastic commercial competition are the driving forces to develop more sustainable and economic processes for important chemicals syntheses in both academic and industrial fields [1,2]. In fine chemical industries, organic solvents still dominate in modern synthetic processes since they are capable of dissolving a wide range of organic compounds and controlling the reaction selectivity and rate. However, they are often volatile, toxic, flammable and expensive as well as might introduce a bulk of hazardous waste treatment issues. Thus, great efforts have been put into reducing or eliminating those organic solvents by replacing them with more environmentally acceptable alternatives [3]. It is beyond doubt that water is a preferred choice because of its abundance, non-toxicity, non-flammability, as well as minimum environmental impacts. In addition, using water as medium often leads to exceptional chemical reactivity and selectivity owing to its unique physicochemical properties [4-6].

The palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions to form C–C bonds are very powerful synthetic tools in modern organic synthesis [7]. With their increasing applications in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, natural products and functional materials [8-10], moving these useful transformations to occurring in aqueous media became more and more attractive [11]. Despite there are several strategies for palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions in water, such as microwave heating [12], ultrasonic irradiation [13,14] and ligand-free methodology [15,16], the more efficient and preferable one is the use of water-soluble ligated palladium catalysts. This approach not only enhances the water solubility of the catalyst, but also facilitates the recovery of the catalyst by separating the aqueous phase and subsequently for the potential reuse of catalyst [17]. Initially, such catalysts have been obtained through modifying traditional palladium–phosphine catalysts by grafting various hydrophilic substituents on phosphine ligands [18-27]. However, most of these phosphine ligands are air sensitive and required tedious work to preparation. In addition, the easy dissociation of common P–Pd bonds under aqueous reaction conditions often restricted the reuse of the catalyst and led to undesired residues. Therefore, in recent years, efforts have been turned to the development of water-soluble non-phosphine ligands [28-34]. In this context, N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) have been recognized as the preferable candidates [35,36]. In contrast to common phosphine- and nitrogen-based ligands, NHCs exhibit stronger σ-donating and weaker π-accepting properties, which make the corresponding Pd–NHC complexes more air and water stable. Furthermore, the convenient functionalization of the N atom of the NHC ring allows for the possible incorporation of water soluble moieties, thus providing more opportunities for water soluble catalyst design [37-39].

Since the pioneering report of a sulfonate-functionalized NHC ligand by Shaughnessy [40], a number of water-soluble NHC ligands, functionalized with sulfonate- [41-46], carboxylate- [47-52], polyether- [53-59] and other hydrophilic groups [60-63], have been developed and used in the aqueous Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Among them, most of them were contributed to Suzuki–Miyaura reactions and only a very few examples were reported for Mizoroki–Heck reactions [45,51,53,57]. Previous research by Rösch and other groups disclosed that introducing a hemilable donor group (such as N, O, S etc.) on the NHC rings was favorable for the palladium-catalyzed Mizoroki–Heck cross-coupling reactions [64,65]. These electron-donating groups could provide a flexible environment for the Pd center and thus favoring the complexation and the migratory insertion of an alkene. Cavell reported that a pyridine functionalized Pd–NHC complex showed outstanding catalytic activity in Mizoroki–Heck reactions with DMF as solvent [66].

With this regards, we herein report the development of a new poly(ethylene glycol, PEG) and pyridine bi-functionalized imidazolium salt L1 (Figure 1), which was employed as a water soluble NHC ligand precursor for an in situ generated Pd–NHC catalyst for Mizoroki–Heck reactions in water. Meanwhile, two analogues, phenyl (L2) and naphthyl (L3) functionalized imidazolium salts were synthesized and their catalytic activities in aqueous Mizoroki–Heck reactions were also studied.

Figure 1: Structures of imidazolium salts L1–L3.

Figure 1: Structures of imidazolium salts L1–L3.

Results and Discussion

PEGs are a kind of highly water soluble polymers from the polymerization of ethylene oxide [67]. Owing to their significant advantages, including widely commercial availability, biocompatibility, chemical and thermal stability and ease to be derived, PEGs have been widely used as phase-transfer catalysts (PTC) or in the preparation of water soluble ligands for aqueous organic reactions during the past decades [68,69]. More recently, several PEG-functionalized azolium salts have been synthesized as water soluble NHC precursors for aqueous Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions [56-59,70]. Fujihara also pointed out that the flexible linear long-chain structure of PEGs could wrap and stabilize the metal center and thus significantly enhanced the catalytic efficiency [70]. Therefore, we chose PEG as functionalization group to prepare water soluble catalysts.

The PEG-functionalized imidazolium salts L1–L3 were prepared via a three-step reaction sequence as depicted in Scheme 1. Firstly, the commercially available MeO-PEG1900-OH was reacted with MsCl using pyridine as base in CH2Cl2 to form MeO-PEG1900-OMs, which was then treated with sodium imidazole in THF to form the imidazole-functionalized PEG (MeO-PEG1900-Im). The resulted MeO-PEG1900-Im was heated with various organic bromides (2-(bromomethyl)pyridine, benzyl bromide and 1-(bromomethyl)naphthalene) to generate the corresponding imidazolium salts L1–L3 under solvent-free conditions. All imidazolium salts were water-soluble and air-stable. The resulted salts L1–L3 were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR and MALDI–TOF–MS analyses (see Supporting Information File 1).

Scheme 1: The synthetic route for the preparation of imidazolium salts L1–L3.

Scheme 1: The synthetic route for the preparation of imidazolium salts L1–L3.

The catalytic performance of the synthesized imidazolium salts as NHC precursors for Pd-catalyzed Mizoroki–Heck reactions in water was investigated. A model reaction was carried out by using 4-bromoacetophenone (1a) and styrene (2a) as the substrates, water as solvent and Na2PdCl4/L1 as the catalyst. The mixture of Na2PdCl4, L1 and base in water were preheated at 60 °C for 30 min before the addition of substrates [41]. The effect of base was first explored. As the selected experimental results illustrated in Table 1, almost no reaction was observed without base at 100 °C for 12 h (entry 1, Table 1). The reaction could be obviously promoted by a wide range of common bases, such as Et3N, NaHCO3, Na2CO3, K2CO3, NaOH, NaOEt and NaOt-Bu. The best result was obtained with NaOEt as the base. With 2.0 equivalents of NaOEt, the desired coupling product 3aa was achieved in 97% GC yield (entry 7, Table 1). Employing NaOt-Bu could also provide an excellent yield (91%, entry 8, Table 1). Weaker bases, such as Et3N and NaHCO3, led to lower yields (entries 2 and 3, Table 1). The performance of NaOEt and NaOt-Bu was obviously better than that of NaOH. To clarify that this improvement might be due to the generation of EtOH and t-BuOH from the hydrolysis of NaOEt and NaOt-Bu in water, we then studied the effect of EtOH and t-BuOH on the reaction. In contrast to the reaction in neat water with NaOH as base, the yields of 3aa were increased from 68% to 88% and 78%, respectively, after the addition of 2.0 equivalents of EtOH and t-BuOH, inferring that EtOH and t-BuOH could facilitate the reaction. However, both of them were inferior to the reactions using NaOEt and NaOt-Bu as the base directly (entries 9 and 10, Table 1). Furthermore, it was found that N2 atmospheric conditions were crucial for the reaction and a nearly quantitative GC yield was resulted with 0.05–0.1 mol % catalyst loadings (entries 11 and 12, Table 1). Further decreasing the catalyst loading to 0.01 mol % resulted in a 89% GC yield of the coupling product 3aa (entry 13, Table 1). Additionally, increasing the molar ratio of L1 and Na2PdCl4 to 1.5 did not obviously affect the yield (entry 14, Table 1). However, without L1, the GC yield of 3aa was dramatically decreased to 25%, which hinted that L1 played a crucial role in this transformation (entry 15, Table 1). We also attempted to carry out the reaction at lower reaction temperature; however, much lower conversion was found (entry 16, Table 1). Moreover, a blank experiment showed that no reaction occurred without Na2PdCl4 (entry 17, Table 1). To confirm that Na2PdCl4 and L1 in situ generated the Pd–NHC species, we treated Na2PdCl4, L1 and NaOEt in D2O at 60 °C for 30 min, and then performed NMR analyses. The 1H NMR spectrum clearly showed that the proton signal of the 2-position (9.41 ppm) of the imidazolium salt L1 disappeared. Two downfield signals at 180.9 and 170.9 ppm appeared in the 13C NMR spectrum, which is similar to the reported 13C NMR analysis for Pd–NHC species [66]. It is strongly suggested that a Pd–NHC complex was formed from deprotonation of L1 under the reaction conditions. However, the exact structure of this complex is not clear yet.

Table 1: Optimizing the reaction conditions of the Mizoroki–Heck reaction.a

|

|

|||

| Entry | Base | Pd:L1 (Pd mol %) | Yieldb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | 1:1 (0.1%) | trace |

| 2 | Et3N | 1:1 (0.1%) | 23 |

| 3 | NaHCO3 | 1:1 (0.1%) | 20 |

| 4 | Na2CO3 | 1:1 (0.1%) | 66 |

| 5 | K2CO3 | 1:1 (0.1%) | 57 |

| 6 | NaOH | 1:1 (0.1%) | 68 |

| 7 | NaOEt | 1:1 (0.1%) | 97 |

| 8 | NaOt-Bu | 1:1 (0.1%) | 91 |

| 9 | NaOH + EtOH (2.0 equiv) | 1:1 (0.1%) | 88 |

| 10 | NaOH + t-BuOH (2.0 equiv) | 1:1 (0.1%) | 78 |

| 11c | NaOEt | 1:1 (0.1%) | >99 |

| 12c | NaOEt | 1:1 (0.05%) | >99 |

| 13c | NaOEt | 1:1 (0.01%) | 89 |

| 14c | NaOEt | 1:1.5 (0.01%) | 88 |

| 15c | NaOEt | 1:0 (0.05%) | 25 |

| 16c,d | NaOEt | 1:1 (0.05%) | 46 |

| 17c,e | NaOEt | – | n.r. |

aReaction conditions: 4-bromoacetophenone (1a, 1.0 mmol), styrene (2a, 1.2 mmol), base (2.0 mmol), Na2PdCl4 (0.001 mmol, 0.1% aqueous solution), L1 (0.001 mmol, 1% aqueous solution), 1.5 mL H2O, 100 °C, 12 h. The mixture of L1, Na2PdCl4 and base in water was preheated in water at 60 °C for 30 min before adding substrates 1a and 2a. bGC yields were determined by using the area normalization method and calculated based on 1a. cPurged with N2. dCarried out at 90 °C. eWithout Na2PdCl4, L1 (0.1 mol %).

With the preliminary reaction conditions in hand, we then further compared the catalytic performance of those Pd-complexes derived from phenyl and naphthyl analogues L2 and L3 with that of pyridine functionalized NHC precursor L1. A kinetic study of the coupling between 4-bromoacetophenone (1a) and styrene (2a) was performed in the presence of 0.01 mol % of Na2PdCl4/L and 2.0 equivalents of NaOEt at 100 °C in water and all the three reactions preceded for 24 h. As shown in Figure 2, the reaction using Na2PdCl4/L1 as the catalyst had a relatively shorter induction period and a higher catalytic activity than those of Na2PdCl4/L2 and Na2PdCl4/L3. After 24 h, a 100% conversion of 1a was observed in the Na2PdCl4/L1 catalytic system, a conversion of 87% in Na2PdCl4/L2 and 77% in Na2PdCl4/L3. This result might be attributed to the side-arm pyridine group acting as a hemilable coordination site and thus enhanced the catalytic activity of the palladium complex in Mizoroki–Heck reactions. Furthermore, the TON of the coupling of 4-bromoacetophenone (1a) and styrene (2a) with Na2PdCl4/L1 as the catalyst was calculated to be 10,000, which is much higher than for previously reported catalytic systems under aqueous conditions.

![[1860-5397-13-168-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-13-168-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Kinetic profiles of Mizoroki–Heck reactions in water, Na2PdCl4/L1 (square), L2 (circle), and L3 (triangle). Reaction conditions: 4-bromoacetophenone (1a, 1.0 mmol), styrene (2a, 1.2 mmol), NaOEt (2.0 mmol), 0.01 mol % Na2PdCl4, Pd/L = 1:1 (molar ratio), 1.5 mL H2O, 100 °C.

Figure 2: Kinetic profiles of Mizoroki–Heck reactions in water, Na2PdCl4/L1 (square), L2 (circle), and L3 (tr...

After obtaining the optimal conditions, we then started to explore the substrate scope of the newly developed catalytic system for Mizoroki–Heck reactions in water. First, a variety of para-substituted phenyl bromides 1a–l were tested to couple with styrene (2a) and the results were summarized in Table 2 (entries 1–12). Under the optimized reaction conditions (0.05 mol % Na2PdCl4 and L1, 100 °C, 2.0 equivalents of NaOEt for 12 h), the coupling reactions of aryl bromides 1a–c with strongly electron-withdrawing substituents (COCH3, CHO and NO2) proceeded smoothly and the desired coupling products 3aa–ca were obtained in almost quantitative yields (entries 1–3, Table 2). However, higher reaction temperature (120 °C) was necessary for the coupling of aryl bromides 1d–g with moderate electron-withdrawing substituents (CF3, F, Cl and Br) and their coupling products 3da–ga could be still obtained in good to excellent yields (87–94%, entries 4–7, Table 2). It was not surprising that substrates of aryl bromides 1h–j with electron-donating substituents (H, CH3 and OCH3) showed rather difficulties for the completion of the reaction. With slightly adjusting the reaction conditions (higher reaction temperature (120 °C) and higher catalyst loading (0.1 mol %), reasonable yields of coupling products 3ha–ja could be obtained (entries 8–10, Table 2). It should be pointed out that in the reaction of 1,4-dibromobenzene (1g), only mono-olefinated product 3ga was formed and not a trace of any di-olefinated product was detected. We also found that amino and hydroxy substituted aryl bromides 1k and 1l exhibited high reactivity in the present aqueous catalytic systems (entries 11 and 12 vs entries 1–3, Table 2). It might be attributed to the hydrogen bonding action between amino or hydroxy groups and water and thus activated these two substrates. Then, the reactivity of meta- or ortho-substituted phenyl bromides 1m–r were examined (entries 13–18, Table 2). Compared with para-substituted analogues 1a, 1b and 1i, the meta-substituted phenyl bromides 1m, 1n and 1o showed slightly lower reactivities under the same reaction conditions (entries 13–15 vs entries 1, 2, 9, Table 2). Nevertheless, the steric hindrance of phenyl bromides with a substituent at the ortho-position obviously stagnated the coupling reaction and the yields of the corresponding coupling products 1pa, 1qa and 1ra were much lower than their para- and meta-substituted analogues (entries 16–18, Table 2). Besides the substituted phenyl bromides, 2-bromonaphthalene (1s) and some N-heteroaromatic bromides (3-bromopyridine (1t) and 3-bromoquinoline (1u)) could smoothly couple with 2a to afford the corresponding coupling products 3sa, 3ta and 3ua in good to excellent yields (84, 97 and 86%, respectively, entries 19–21, Table 2).

Table 2: Mizoroki–Heck reactions between substituted aryl bromides and styrene.a

|

|

|||||

| Entry | Ar–Br 1 (R) | Product 3 | Pd/L1 (mol %) | T (°C) | Yieldb (%) |

|

|

|

||||

| 1 | 1a (R = COCH3) | 3aa | 0.05 | 100 | 96 |

| 2 | 1b (R = CHO) | 3ba | 0.05 | 100 | 98 |

| 3 | 1c(R = NO2) | 3ca | 0.05 | 100 | 95 |

| 4 | 1d (R = CF3) | 3da | 0.05 | 120 | 94 |

| 5 | 1e (R = F) | 3ea | 0.05 | 120 | 87 |

| 6 | 1f (R = Cl) | 3fa | 0.05 | 120 | 90 |

| 7 | 1g (R = Br) | 3ga | 0.05 | 120 | 87 |

| 8 | 1h (R = H) | 3ha | 0.1 | 120 | 76 |

| 9 | 1i (R = CH3) | 3ia | 0.1 | 120 | 88 |

| 10 | 1j (R = OCH3) | 3ja | 0.1 | 120 | 53 |

| 11 | 1k (R = NH2) | 3ka | 0.05 | 100 | 87 |

| 12c | 1l (R = OH) | 3la | 0.05 | 100 | 65 |

|

|

|

||||

| 13 | 1m (3-COCH3) | 3ma | 0.05 | 100 | 91 |

| 14 | 1n (3-CHO) | 3na | 0.05 | 100 | 89 |

| 15 | 1o (3-CH3) | 3oa | 0.1 | 120 | 77 |

|

|

|

||||

| 16 | 1p (2-COCH3) | 3pa | 0.05 | 100 | <10 |

| 17 | 1q (2-CHO) | 3qa | 0.05 | 100 | 51 |

| 18 | 1r (2-CH3) | 3ra | 0.1 | 120 | 73 |

| 19 |

1s |

3sa |

0.1 | 120 | 84 |

| 20 |

1t |

3ta |

0.05 | 120 | 97 |

| 21 |

1u |

3ua |

0.05 | 120 | 86 |

aReaction conditions: Ar–Br 1 (1.0 mmol), styrene (2a, 1.2 mmol), NaOEt (2.0 mmol), Na2PdCl4 (0.05–0.1 mol %, 0.1% aqueous solution), L1 (0.05–0.1 mol %, 1% aqueous solution), 1.5 mL H2O, 100 °C, 12 h, purged with N2. The mixture of L1, Na2PdCl4 and base in water was preheated in water at 60 °C for 30 min before adding substrates 1 and 2a. bIsolated yields. c3.0 Equivalents of NaOEt was used.

The scope of alkenes was also investigated to couple with 4-bromoacetophenone in water (Table 3). These alkenes included para-substituted styrenes 2b–d (OCH3, CH3 and Cl), 2-vinylnaphthalene (2e), acrylic acid (2f), 4-vinylpyridine (2g), as well as an internal alkene ((E)-stilbene, (2h)). To our delight, all these tested alkenes smoothly transformed into the corresponding products 3ab–ah in excellent yields (85–97%) with 0.05–0.1 mol % of Na2PdCl4/L1 at 100 or 120 °C (Table 3). It is noteworthy that a trace amount of 1,1-disubstituted ethylene isomers and/or Z-isomers in coupling products were also observed in some cases. However, the selectivity of E-isomers were always over 99% according to GC analyses.

Table 3: Mizoroki–Heck reactions between 4-bromoacetophenone and various alkenes.a

|

|

|||||

| Entry | Alkene 2 | Product 3 | Pd/L1 (mol %) | T (°C) | Yieldb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

2b |

3ab |

0.05 | 100 | 97 |

| 2 |

2c |

3ac |

0.05 | 100 | 95 |

| 3 |

2d |

3ad |

0.05 | 100 | 93 |

| 4 |

2e |

3ae |

0.05 | 100 | 96 |

| 5c |

2f |

3af |

0.1 | 120 | 89 |

| 6 |

2g |

3ag |

0.1 | 120 | 85 |

| 7 |

2h |

3ah |

0.05 | 120 | 93 |

aReaction conditions: 4-bromoacetophenone (1a, 1.0 mmol), alkenes 2 (1.2 mmol), NaOEt (2.0 mmol), Na2PdCl4 (0.05–0.1 mol %, 0.1% aqueous solution), L1 (0.05–0.1 mol %, 0.1% aqueous solution), 1.5 mL H2O, 100 °C, 12 h, purged with N2. The mixture of L1, Na2PdCl4 and base in water was preheated in water at 60 °C for 30 min before adding substrates 1a and 2. bIsolated yields. c3.0 Equivalents of NaOEt was used.

One of the important advantages of using water-soluble catalysts for reactions in water is the easy isolation of products by extraction with a water immiscible solvent, while retaining the catalyst in the aqueous phase for recovery and potential reuse. Therefore, the recyclability of the Na2PdCl4/L1 catalytic system for Mizoroki–Heck reactions in water was examined by using the coupling of 4-bromoacetophenone (1a) and styrene (2a) under the optimal conditions as a model reaction. After each cycle, the yielded coupling product was extracted with MTBE. Then, fresh 4-bromoacetophenone, styrene and base were added into the catalyst-containing aqueous phase for further reaction. The results in Figure 3 show that the conversion of 4-bromoacetophenone was 85% for first recycle and 56% for second recycle, while the selectivity of (E)-4-acetylstilbene (3aa) was unchanged (>99%), which revealed that the catalytic system still remained certain catalytic activity.

![[1860-5397-13-168-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-13-168-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Reusability of the Na2PdCl4/L1 catalytic system for the catalytic Mizoroki–Heck coupling reaction of 4-bromoacetophene (1a) and styrene (2a).

Figure 3: Reusability of the Na2PdCl4/L1 catalytic system for the catalytic Mizoroki–Heck coupling reaction o...

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed three PEG-functionalized imidazolium salts L1–L3 from commercially available MeO-PEG1900-OH, imidazole, and various arylmethyl bromides (2-bromomethylpyridine for L1, benzyl bromide for L2 and 1-bromomethylnaphthalene for L3). It was shown that these imidazolium salts L1–L3 could be utilized as water soluble NHC ligand precursors in combination with Na2PdCl4 to form in situ the corresponding Pd–NHC catalysts for Mizoroki–Heck reactions in water without any organic co-solvent or phase transfer reagent. The results indicate that L1 bearing a side-armed pyridine at N3-position of the imidazole ring exhibited the best catalytic activity in Mizoroki–Heck reactions, in which the pyridine group might serve as a hemilable donating functional group in the catalytic process. For the coupling of 4-bromoacetophenone and styrene, the TON of Na2PdCl4/L1 catalytic system reached up to 10,000. Under the optimal conditions, large amounts of substituted alkenes were obtained in good to excellent yields using the Na2PdCl4/L1 catalyst system with only a 0.05–0.1 mol % palladium loading. To the best of our knowledge, the catalyst loading in the current report for aqueous Mizoroki–Heck couplings of aryl bromides is much lower than other previously reported counterparts. Moreover, imidazolium salt L1 was conveniently synthesized from commercially available materials. This newly developed protocol provides an efficient, practical and environmental benign method for the construction of various alkene derivatives.

Experimental

General

All chemicals were reagent grade and used as purchased. Monomethylated PEG1900 (MeO-PEG1900-OH) was obtained from Meryer Chem. Tech. Co. Ltd, China. All proton and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE III 500 MHz spectrometer in deuterated solvents with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal standard. Mass spectrometry data (MALDI–TOF) of the three imidazolium salts L1–L3 were collected on a Bruker ultrafleXtreme mass spectrometer. Low-resolution mass analyses were performed on a Thermo Trace ISQ GC–MS instrument in EI mode (70 eV) or a Thermo Scientific ITQ 1100TM mass spectrometer in ESI mode. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded in the EI mode on a Waters GCT Premier TOF mass spectrometer with an Agilent 6890 gas chromatography using a DB-XLB column (30 m × 0.25 mm (i.d.), 0.25 μm). Melting points (uncorrected) were determined on a Büchi M-565 apparatus. Gas chromatography (GC) analyses were performed on Shimadzu GC-20A instrument with FID detector using a RTX-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm (i.d.), 0.25 μm). Flash column chromatography was performed on silica gel (200–300 mesh) with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate as eluent. De-ionized water was used in all reactions.

Preparation of PEG-functionalized imidazolium salts L1, L2 and L3

Synthesis of MeO-PEG1900-OMs

MeO-PEG1900-OH (38.0 g , 0.02 mol) and pyridine (3.16 g, 0.04 mol) were dissolved in 50 mL of dry DCM at an ice-water bath and under N2 atmosphere, followed by adding dropwise a solution of methanesulfonyl chloride (MsCl, 4.58 g, 0.04 mol) in 200 mL of dry DCM. After completion of addition, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The reaction was quenched with 100 mL of ice-water and the pH was adjusted to 7 with a 20% aqueous NaOH solution. The organic layer was separated, washed with water, dried with Na2SO4 and filtered. After removal of the solvent under vacuum, the residual was precipitated with methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) to afford 38.3 g (97%) of MeO-PEG1900-OMs as a white solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.34–4.32 (m, 2H, CH2OMs), 3.74–3.44 (m, 198H, CH2 of PEG chain), 3.33 (s, 3H, PEG-OCH3), 3.04 (s, 3H, SO2CH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 71.9–68.2 (CPEG), 60.7, 58.2, 36.8.

Synthesis of MeO-PEG1900-Im

To a solution of imidazole (0.89 g, 13 mmol) in 120 mL of dry THF at room temperature under N2 atmosphere was added NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil, 0.8 g, 20 mmol). The mixture was then heated to 40 °C for 1 h to ensure the completion of H2 releasing. After that, MeO-PEG1900-OMs (19.7 g, 10 mmol) was added and the mixture was refluxed for 24 h. Then, the resulting suspension was filtered off and the filtrate was concentrated under vacuum. Precipitation with MTBE afforded 18.2 g (93%) of MeO-PEG1900-Im as a light yellow solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.50 (s, 1H, CHimid), 6.96 (s, 1H, CHimid), 6.95 (s, 1H, CHimid), 4.05 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 3.68 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H, NCH2), 3.58–3.42 (m, 196H, CH2 of PEG chain), 3.30 (s, 3H, PEG-OCH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 136.8, 128.2, 118.8, 71.2–69.8 (CPEG), 58.2, 46.3.

Synthesis of imidazolium salts L1, L2 and L3

A mixture of MeO-PEG1900-Im (3.9 g, 2 mmol) and the corresponding organic bromide (2.4 mmol) was heated in a sealed tube at 100 oC for 24 h. The resulting imidazolium salts was isolated by precipitation with MTBE.

Imidazolium salt L1. Yield: 3.9 g (92%), pale brown solid; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.41 (s, 1H, CHimid), 8.56 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H, CHpyri), 7.92–7.88 (m, 1H, CHpyri), 7.84 (s, 2H, CHpyri), 7.53 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, CHimid), 7.41 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, CHimid), 5.64 (s, 2H, CHbenzyl), 4.43 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 3.81 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H, NCH2), 3.66–3.42 (m, 196H, CH2 of PEG chain), 3.24 (s, 3H, PEG-OCH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 153.7, 149.6, 137.6, 137.3, 123.7, 123.0, 122.9, 122.7, 71.2–68.3 (CPEG), 58.1, 53.0, 49.0; MALDI–TOF–MS m/z: [Mn=49 − Br]+ calcd for C110H212N3O50, 2375.4; found, 2375.8.

Imidazolium salt L2. Yield: 3.9 g (92%), pale white solid; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.28 (s, 1H, CHimid), 7.85–7.80 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.44–7.40 (m, 5H, CHAr), 5.46 (s, 2H, CHbenzyl), 4.38 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 3.79 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H, NCH2), 3.51–3.42 (m, 196H, CH2 of PEG chain), 3.24 (s, 3H, PEG-OCH3); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 136.6, 135.0, 128.9, 128.7, 128.4, 123.1, 122.2, 71.34–68.2 (CPEG), 58.0, 51.7, 49.0; MALDI–TOF–MS m/z: [Mn=49 − Br]+ calcd for C111H213N2O50, 2374.4; found, 2374.8.

Imidazolium salt L3. Yield: 3.8 g (88%), pale white solid; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.28 (s, 1H, CHimid), 8.15 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, CHAr), 8.04–8.03 (m, 2H, CHAr), 7.84 (s, 1H, CHAr), 7.80 (s, 1H, CHAr), 7.64–7.57 (m, 3H, CHAr), 7.52 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H, CHimid), 5.98 (s, 2H, CHbenzyl), 4.36 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 3.76 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H, NCH2), 3.51–3.41 (m, 196H, CH2 of PEG chain), 3.24 (s, 3H, PEG-OCH3); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 136.7, 133.5, 130.5, 130.2, 129.7, 128.9, 127.8, 127.2, 126.4, 125.6, 123.02, 122.97, 122.5, 71.3–68.1 (CPEG), 58.0, 49.8, 49.0; MALDI–TOF–MS m/z: [Mn=49 − Br]+ calcd for C115H215N2O50, 2424.4; found, 2424.9.

General procedure for Mizoroki–Heck reactions in water

To a 10 mL tube, Na2PdCl4 (0.1% aqueous solution, 0.05–0.1 mol %), imidazolium salts L1–L3 (1% aqueous solution, 0.05–0.1 mol %), NaOEt (2.0 mmol) and 1.5 mL water were successively added, followed by preheating at 60 °C for 30 min. Then, aryl bromide (1.0 mmol) and styrene (1.2 mmol) were added, purged with N2, sealed and heated at 100 °C. After 12 h, the solution was extracted with MTBE (5 mL × 2) and the organic layers combined, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuum. Finally, the resulted residual were purified by flash chromatography on silica to afford the desired cross-coupling alkene products. The purity of the obtained products was confirmed by NMR and the yields were based on aryl bromides.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Characterization data of Mizoroki–Heck products and copies of NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 3.5 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (21473160). We also thank for the support from “Zhejiang Key Course of Chemical Engineering and Technology” and “Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Green Pesticides and Cleaner Production Technology of Zhejiang Province” of the Zhejiang University of Technology.

References

-

Anastas, P.; Eghbali, N. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 301–312. doi:10.1039/B918763B

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheldon, R. A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1437–1451. doi:10.1039/C1CS15219J

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheldon, R. A. Green Chem. 2005, 7, 267–278. doi:10.1039/b418069k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, C.-J.; Chan, T.-H. Organic reactions in aqueous media; Wiley-VCH: New York, 1997.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Butler, R. N.; Coyne, A. G. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6302–6337. doi:10.1021/cr100162c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Simon, M.-O.; Li, C.-J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1415–1427. doi:10.1039/C1CS15222J

Return to citation in text: [1] -

de Meijere, A.; Diederich, F. Metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2008. doi:10.1002/9783527619535

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nicolaou, K. C.; Bulger, P. G.; Sarlah, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4442–4489. doi:10.1002/anie.200500368

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Torborg, C.; Beller, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 3027–3043. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900587

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Magano, J.; Dunetz, J. R. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 2177–2250. doi:10.1021/cr100346g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, C.-J. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3095–3166. doi:10.1021/cr030009u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dallinger, D.; Kappe, C. O. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2563–2591. doi:10.1021/cr0509410

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Poláčková, V.; Hut'ka, M.; Toma, Š. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2005, 12, 99–102. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.05.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Z.; Zha, Z.; Gan, C.; Pan, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, M.-M. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 4339–4342. doi:10.1021/jo060372b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bumagin, N. A.; More, P. G.; Beletskaya, I. P. J. Organomet. Chem. 1989, 371, 397–401. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(89)85235-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Basu, B.; Biswas, K.; Kundu, S.; Ghosh, S. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1734–1738. doi:10.1039/c0gc00122h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shaughnessy, K. H. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 643–710. doi:10.1021/cr800403r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Casalnuovo, A. L.; Calabrese, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4324–4330. doi:10.1021/ja00167a032

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Genet, J. P.; Blart, E.; Savignac, M. Synlett 1992, 715–717. doi:10.1055/s-1992-21465

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bumagin, N. A.; Bykov, V. V.; Sukhomlinova, L. I.; Tolstaya, T. P.; Beletskaya, I. P. J. Organomet. Chem. 1995, 486, 259–262. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(94)05056-H

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Genet, J. P.; Savignac, M. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999, 576, 305–317. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(98)01088-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Uozumi, Y.; Kimura, T. Synlett 2002, 2045–2048. doi:10.1055/s-2002-35605

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Amengual, R.; Genin, E.; Michelet, V.; Savignac, M.; Genet, J. P. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2002, 344, 393–398. doi:10.1002/1615-4169(200206)344:3/4<393::AID-ADSC393>3.0.CO;2-K

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moore, L. R.; Shaughnessy, K. H. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 225–228. doi:10.1021/ol0360288

Return to citation in text: [1] -

DeVasher, R. B.; Moore, L. R.; Shaughnessy, K. H. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 7919–7927. doi:10.1021/jo048910c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shaughnessy, K. H. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 1827–1835. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200500972

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jeffery, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 3051–3054. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)76825-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Azoui, H.; Baczko, K.; Cassel, S.; Larpent, C. Green Chem. 2008, 10, 1197–1203. doi:10.1039/b804828b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pawar, S. S.; Dekhane, D. V.; Shingare, M. S.; Thore, S. N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 4252–4255. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.04.148

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, G.; Luan, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, X.; Ding, C.; Gao, J. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 2081–2085. doi:10.1039/c3gc40645h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nehra, P.; Khungar, B.; Pericherla, K.; Sivasubramanian, S. C.; Kumar, A. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 4266–4271. doi:10.1039/C4GC00525B

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Potier, J.; Menuel, S.; Rousseau, J.; Tumkevicius, S.; Hapiot, F.; Monflier, E. Appl. Catal., A 2014, 479, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2014.04.021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khan, R. I.; Pitchumani, K. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 5518–5528. doi:10.1039/C6GC01326K

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Waheed, M.; Ahmed, N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 3785–3789. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.07.028

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Herrmann, W. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1290–1309. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020415)41:8<1290::AID-ANIE1290>3.0.CO;2-Y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kantchev, E. A. B.; O'Brien, C. J.; Organ, M. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2768–2813. doi:10.1002/anie.200601663

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Velazquez, H. D.; Verpoort, F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7032–7060. doi:10.1039/c2cs35102a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schaper, L.-A.; Hock, S. J.; Herrmann, W. A.; Kühn, F. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 270–289. doi:10.1002/anie.201205119

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Levin, E.; Ivry, E.; Diesendruck, C. E.; Lemcoff, N. G. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4607–4692. doi:10.1021/cr400640e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moore, L. R.; Cooks, S. M.; Anderson, M. S.; Schanz, H.-J.; Griffin, S. T.; Rogers, R. D.; Kirk, M. C.; Shaughnessy, K. H. Organometallics 2006, 25, 5151–5158. doi:10.1021/om060552b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fleckenstein, C.; Roy, S.; Leuthäußer, S.; Plenio, H. Chem. Commun. 2007, 2870–2872. doi:10.1039/B703658B

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Roy, S.; Plenio, H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 1014–1022. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900886

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Türkmen, H.; Pelit, L.; Çetinkaya, B. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2011, 348, 88–93. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2011.08.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Godoy, F.; Segarra, C.; Poyatos, M.; Peris, E. Organometallics 2011, 30, 684–688. doi:10.1021/om100960t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yuan, D.; Teng, Q.; Huynh, H. V. Organometallics 2014, 33, 1794–1800. doi:10.1021/om500140g

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhong, R.; Pöthig, A.; Feng, Y.; Riener, K.; Herrmann, W. A.; Kühn, F. E. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 4955–4962. doi:10.1039/C4GC00986J

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Churruca, F.; SanMartin, R.; Inés, B.; Tellitu, I.; Domínguez, E. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006, 348, 1836–1840. doi:10.1002/adsc.200606173

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Inés, B.; SanMartin, R.; Jesús Moure, M.; Domínguez, E. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 2124–2132. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900345

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Türkmen, H.; Can, R.; Çetinkaya, B. Dalton Trans. 2009, 7039–7044. doi:10.1039/b907032j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tu, T.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 10598–10600. doi:10.1039/c0dt01083a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Z.; Feng, X.; Fang, W.; Tu, T. Synlett 2011, 951–954. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1259723

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Wang, R.; Hong, M. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2071–2077. doi:10.1039/c1gc15312a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gülcemal, S.; Kahraman, S.; Daran, J.-C.; Çetinkaya, E.; Çetinkaya, B. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 3580–3589. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.07.010

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Rao, B.; Luo, M. Organometallics 2009, 28, 3093–3099. doi:10.1021/om8011695

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karimi, B.; Akhavan, P. F. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7686–7688. doi:10.1039/c1cc00017a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, N.; Liu, C.; Jin, Z. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 592–597. doi:10.1039/c2gc16486h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Long, E. Transition Met. Chem. 2014, 39, 11–15. doi:10.1007/s11243-013-9765-x

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Shi, J.-c.; Yu, H.; Jiang, D.; Yu, M.; Huang, Y.; Nong, L.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, Z. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 158–164. doi:10.1007/s10562-013-1126-z

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhen, H.; Lin, Z.; Ling, Q. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 30, 924–931. doi:10.1002/aoc.3522

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yang, C.-C.; Lin, P.-S.; Liu, F.-C.; Lin, I. J. B. Organometallics 2010, 29, 5959–5971. doi:10.1021/om100751r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, F.-T.; Lo, H.-K. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1262–1265. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.11.002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, Z.; Qiu, J.; Xie, L.; Du, F.; Xu, G.; Xie, Y.; Ling, Q. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 1911–1918. doi:10.1007/s10562-014-1323-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meise, M.; Haag, R. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 637–642. doi:10.1002/cssc.200800042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Albert, K.; Gisdakis, P.; Rösch, N. Organometallics 1998, 17, 1608–1616. doi:10.1021/om9709190

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Normand, A. T.; Cavell, K. J. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2781–2800. doi:10.1002/ejic.200800323

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McGuinness, D. S.; Cavell, K. J. Organometallics 2000, 19, 741–748. doi:10.1021/om990776c

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chen, J.; Spear, S. K.; Huddleston, J. G.; Rogers, R. D. Green Chem. 2005, 7, 64–82. doi:10.1039/b413546f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bergbreiter, D. E. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 3345–3383. doi:10.1021/cr010343v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bergbreiter, D. E.; Tian, J.; Hongfa, C. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 530–582. doi:10.1021/cr8004235

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fujihara, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Satou, M.; Ohta, H.; Terao, J.; Tsuji, Y. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 17382–17385. doi:10.1039/C5CC07588B

Return to citation in text: [1] [2]

| 66. | McGuinness, D. S.; Cavell, K. J. Organometallics 2000, 19, 741–748. doi:10.1021/om990776c |

| 1. | Anastas, P.; Eghbali, N. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 301–312. doi:10.1039/B918763B |

| 2. | Sheldon, R. A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1437–1451. doi:10.1039/C1CS15219J |

| 8. | Nicolaou, K. C.; Bulger, P. G.; Sarlah, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4442–4489. doi:10.1002/anie.200500368 |

| 9. | Torborg, C.; Beller, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 3027–3043. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900587 |

| 10. | Magano, J.; Dunetz, J. R. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 2177–2250. doi:10.1021/cr100346g |

| 40. | Moore, L. R.; Cooks, S. M.; Anderson, M. S.; Schanz, H.-J.; Griffin, S. T.; Rogers, R. D.; Kirk, M. C.; Shaughnessy, K. H. Organometallics 2006, 25, 5151–5158. doi:10.1021/om060552b |

| 7. | de Meijere, A.; Diederich, F. Metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2008. doi:10.1002/9783527619535 |

| 41. | Fleckenstein, C.; Roy, S.; Leuthäußer, S.; Plenio, H. Chem. Commun. 2007, 2870–2872. doi:10.1039/B703658B |

| 42. | Roy, S.; Plenio, H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 1014–1022. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900886 |

| 43. | Türkmen, H.; Pelit, L.; Çetinkaya, B. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2011, 348, 88–93. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2011.08.008 |

| 44. | Godoy, F.; Segarra, C.; Poyatos, M.; Peris, E. Organometallics 2011, 30, 684–688. doi:10.1021/om100960t |

| 45. | Yuan, D.; Teng, Q.; Huynh, H. V. Organometallics 2014, 33, 1794–1800. doi:10.1021/om500140g |

| 46. | Zhong, R.; Pöthig, A.; Feng, Y.; Riener, K.; Herrmann, W. A.; Kühn, F. E. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 4955–4962. doi:10.1039/C4GC00986J |

| 4. | Li, C.-J.; Chan, T.-H. Organic reactions in aqueous media; Wiley-VCH: New York, 1997. |

| 5. | Butler, R. N.; Coyne, A. G. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6302–6337. doi:10.1021/cr100162c |

| 6. | Simon, M.-O.; Li, C.-J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1415–1427. doi:10.1039/C1CS15222J |

| 35. | Herrmann, W. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1290–1309. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020415)41:8<1290::AID-ANIE1290>3.0.CO;2-Y |

| 36. | Kantchev, E. A. B.; O'Brien, C. J.; Organ, M. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2768–2813. doi:10.1002/anie.200601663 |

| 37. | Velazquez, H. D.; Verpoort, F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7032–7060. doi:10.1039/c2cs35102a |

| 38. | Schaper, L.-A.; Hock, S. J.; Herrmann, W. A.; Kühn, F. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 270–289. doi:10.1002/anie.201205119 |

| 39. | Levin, E.; Ivry, E.; Diesendruck, C. E.; Lemcoff, N. G. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4607–4692. doi:10.1021/cr400640e |

| 15. | Bumagin, N. A.; More, P. G.; Beletskaya, I. P. J. Organomet. Chem. 1989, 371, 397–401. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(89)85235-0 |

| 16. | Basu, B.; Biswas, K.; Kundu, S.; Ghosh, S. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1734–1738. doi:10.1039/c0gc00122h |

| 18. | Casalnuovo, A. L.; Calabrese, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4324–4330. doi:10.1021/ja00167a032 |

| 19. | Genet, J. P.; Blart, E.; Savignac, M. Synlett 1992, 715–717. doi:10.1055/s-1992-21465 |

| 20. | Bumagin, N. A.; Bykov, V. V.; Sukhomlinova, L. I.; Tolstaya, T. P.; Beletskaya, I. P. J. Organomet. Chem. 1995, 486, 259–262. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(94)05056-H |

| 21. | Genet, J. P.; Savignac, M. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999, 576, 305–317. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(98)01088-2 |

| 22. | Uozumi, Y.; Kimura, T. Synlett 2002, 2045–2048. doi:10.1055/s-2002-35605 |

| 23. | Amengual, R.; Genin, E.; Michelet, V.; Savignac, M.; Genet, J. P. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2002, 344, 393–398. doi:10.1002/1615-4169(200206)344:3/4<393::AID-ADSC393>3.0.CO;2-K |

| 24. | Moore, L. R.; Shaughnessy, K. H. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 225–228. doi:10.1021/ol0360288 |

| 25. | DeVasher, R. B.; Moore, L. R.; Shaughnessy, K. H. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 7919–7927. doi:10.1021/jo048910c |

| 26. | Shaughnessy, K. H. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 1827–1835. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200500972 |

| 27. | Jeffery, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 3051–3054. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)76825-0 |

| 13. | Poláčková, V.; Hut'ka, M.; Toma, Š. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2005, 12, 99–102. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.05.011 |

| 14. | Zhang, Z.; Zha, Z.; Gan, C.; Pan, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, M.-M. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 4339–4342. doi:10.1021/jo060372b |

| 28. | Azoui, H.; Baczko, K.; Cassel, S.; Larpent, C. Green Chem. 2008, 10, 1197–1203. doi:10.1039/b804828b |

| 29. | Pawar, S. S.; Dekhane, D. V.; Shingare, M. S.; Thore, S. N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 4252–4255. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.04.148 |

| 30. | Zhang, G.; Luan, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, X.; Ding, C.; Gao, J. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 2081–2085. doi:10.1039/c3gc40645h |

| 31. | Nehra, P.; Khungar, B.; Pericherla, K.; Sivasubramanian, S. C.; Kumar, A. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 4266–4271. doi:10.1039/C4GC00525B |

| 32. | Potier, J.; Menuel, S.; Rousseau, J.; Tumkevicius, S.; Hapiot, F.; Monflier, E. Appl. Catal., A 2014, 479, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2014.04.021 |

| 33. | Khan, R. I.; Pitchumani, K. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 5518–5528. doi:10.1039/C6GC01326K |

| 34. | Waheed, M.; Ahmed, N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 3785–3789. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.07.028 |

| 12. | Dallinger, D.; Kappe, C. O. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2563–2591. doi:10.1021/cr0509410 |

| 60. | Yang, C.-C.; Lin, P.-S.; Liu, F.-C.; Lin, I. J. B. Organometallics 2010, 29, 5959–5971. doi:10.1021/om100751r |

| 61. | Luo, F.-T.; Lo, H.-K. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1262–1265. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.11.002 |

| 62. | Zhou, Z.; Qiu, J.; Xie, L.; Du, F.; Xu, G.; Xie, Y.; Ling, Q. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 1911–1918. doi:10.1007/s10562-014-1323-4 |

| 63. | Meise, M.; Haag, R. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 637–642. doi:10.1002/cssc.200800042 |

| 47. | Churruca, F.; SanMartin, R.; Inés, B.; Tellitu, I.; Domínguez, E. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006, 348, 1836–1840. doi:10.1002/adsc.200606173 |

| 48. | Inés, B.; SanMartin, R.; Jesús Moure, M.; Domínguez, E. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 2124–2132. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900345 |

| 49. | Türkmen, H.; Can, R.; Çetinkaya, B. Dalton Trans. 2009, 7039–7044. doi:10.1039/b907032j |

| 50. | Tu, T.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 10598–10600. doi:10.1039/c0dt01083a |

| 51. | Wang, Z.; Feng, X.; Fang, W.; Tu, T. Synlett 2011, 951–954. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1259723 |

| 52. | Li, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Wang, R.; Hong, M. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2071–2077. doi:10.1039/c1gc15312a |

| 53. | Gülcemal, S.; Kahraman, S.; Daran, J.-C.; Çetinkaya, E.; Çetinkaya, B. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 3580–3589. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.07.010 |

| 54. | Zhang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Rao, B.; Luo, M. Organometallics 2009, 28, 3093–3099. doi:10.1021/om8011695 |

| 55. | Karimi, B.; Akhavan, P. F. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7686–7688. doi:10.1039/c1cc00017a |

| 56. | Liu, N.; Liu, C.; Jin, Z. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 592–597. doi:10.1039/c2gc16486h |

| 57. | Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Long, E. Transition Met. Chem. 2014, 39, 11–15. doi:10.1007/s11243-013-9765-x |

| 58. | Shi, J.-c.; Yu, H.; Jiang, D.; Yu, M.; Huang, Y.; Nong, L.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, Z. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 158–164. doi:10.1007/s10562-013-1126-z |

| 59. | Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhen, H.; Lin, Z.; Ling, Q. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 30, 924–931. doi:10.1002/aoc.3522 |

| 70. | Fujihara, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Satou, M.; Ohta, H.; Terao, J.; Tsuji, Y. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 17382–17385. doi:10.1039/C5CC07588B |

| 41. | Fleckenstein, C.; Roy, S.; Leuthäußer, S.; Plenio, H. Chem. Commun. 2007, 2870–2872. doi:10.1039/B703658B |

| 68. | Bergbreiter, D. E. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 3345–3383. doi:10.1021/cr010343v |

| 69. | Bergbreiter, D. E.; Tian, J.; Hongfa, C. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 530–582. doi:10.1021/cr8004235 |

| 56. | Liu, N.; Liu, C.; Jin, Z. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 592–597. doi:10.1039/c2gc16486h |

| 57. | Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Long, E. Transition Met. Chem. 2014, 39, 11–15. doi:10.1007/s11243-013-9765-x |

| 58. | Shi, J.-c.; Yu, H.; Jiang, D.; Yu, M.; Huang, Y.; Nong, L.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, Z. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 158–164. doi:10.1007/s10562-013-1126-z |

| 59. | Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhen, H.; Lin, Z.; Ling, Q. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 30, 924–931. doi:10.1002/aoc.3522 |

| 70. | Fujihara, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Satou, M.; Ohta, H.; Terao, J.; Tsuji, Y. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 17382–17385. doi:10.1039/C5CC07588B |

| 66. | McGuinness, D. S.; Cavell, K. J. Organometallics 2000, 19, 741–748. doi:10.1021/om990776c |

| 67. | Chen, J.; Spear, S. K.; Huddleston, J. G.; Rogers, R. D. Green Chem. 2005, 7, 64–82. doi:10.1039/b413546f |

| 45. | Yuan, D.; Teng, Q.; Huynh, H. V. Organometallics 2014, 33, 1794–1800. doi:10.1021/om500140g |

| 51. | Wang, Z.; Feng, X.; Fang, W.; Tu, T. Synlett 2011, 951–954. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1259723 |

| 53. | Gülcemal, S.; Kahraman, S.; Daran, J.-C.; Çetinkaya, E.; Çetinkaya, B. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 3580–3589. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.07.010 |

| 57. | Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Long, E. Transition Met. Chem. 2014, 39, 11–15. doi:10.1007/s11243-013-9765-x |

| 64. | Albert, K.; Gisdakis, P.; Rösch, N. Organometallics 1998, 17, 1608–1616. doi:10.1021/om9709190 |

| 65. | Normand, A. T.; Cavell, K. J. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2781–2800. doi:10.1002/ejic.200800323 |

© 2017 Sun et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)