Abstract

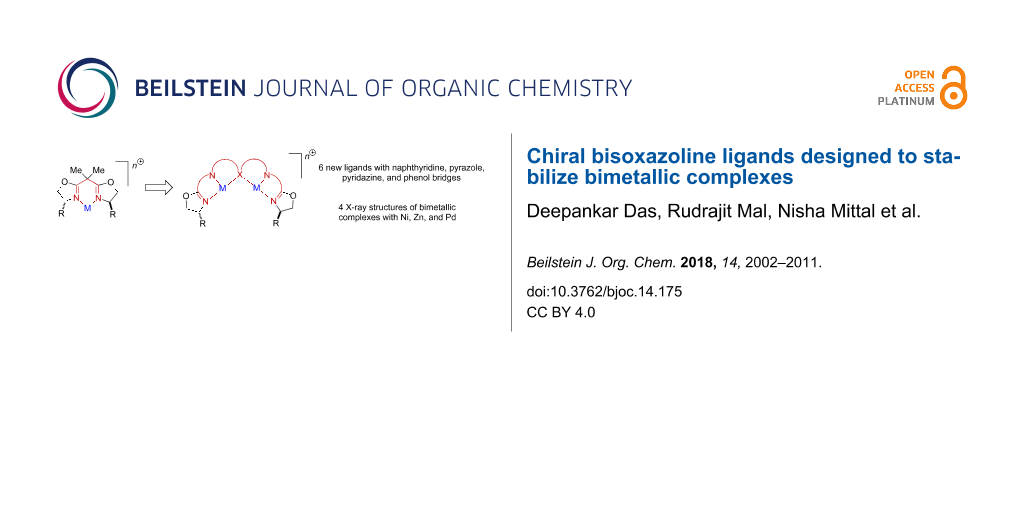

Chiral bisoxazoline ligands containing naphthyridine, pyridazine, pyrazole, and phenol bridging units were prepared and shown to form bimetallic complexes with various metal salts. X-ray crystal structures of bis-nickel naphthyridine-bridged, bis-zinc pyridazine-bridged, and bis-nickel as well as bis-palladium pyrazole-bridged complexes were obtained.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Metal-centered asymmetric catalysis most commonly relies on monometallic complexes of various chiral ligands, among which chiral bisoxazolines have been highly successful in facilitating various Lewis acid-catalyzed asymmetric transformations [1-3]. In addition to monometallic catalysis, it has long been recognized that catalysts possessing two or more metal centers in close proximity can be uniquely effective in catalyzing certain types of reactions [4-6]. Serving as a main source of inspiration in the design of chiral small-molecule systems, nature utilizes a variety of bimetallic and multi-metallic protein complexes to perform a host of biological functions [7]. Urease [8], hemerythrin [9], methane monooxygenase [10], ribonucleotide reductase [11], catechol oxidase [12], and arginase [13], are prominent examples of such bimetallic enzymes.

A range of bi- and multi-metallic complexes have been utilized in asymmetric catalysis (Figure 1) [6]. For instance, Shibasaki and co-workers introduced a number of chiral multi-metallic complexes such as the hetero-bimetallic complex 1, in which the two different metals play distinct roles [14,15]. Jacobsen and co-workers reported dimeric salen complexes 2 which show cooperative reactivity between the two metal centers in the asymmetric ring opening of meso-epoxides [16]. Trost et al. disclosed the synthesis of dinuclear zinc complexes 3 and their application to enantioselective Aldol reactions [17,18] and a host of other asymmetric transformations [18]. Other notable contributions in this area were provided by the groups of Martell [19,20], Maruoka [21,22], Wuest [4,23-25], and others [26-46]. In the majority of cases where bimetallic complexes are used as the catalytically active species, the two metal centers perform different functions [47,48].

Figure 1: Examples of chiral bimetallic complexes utilized in asymmetric catalysis.

Figure 1: Examples of chiral bimetallic complexes utilized in asymmetric catalysis.

Efforts toward synthesizing bisoxazoline ligands capable of concurrently binding to two metal centers have been rather limited. Previous work by Pfaltz, Fahrni, Tsukada, Bellemin-Laponnaz and our group resulted in the synthesis of bisoxazoline containing ligands 6–13 that can simultaneously bind to two metals (Figure 2). For instance, treatment of 6 with two equivalents of copper perchlorate hexahydrate led to the formation of a bis-copper complex [49,50]. The two Cu(ΙΙ) ions, which have a Cu∙∙∙Cu distance of 2.947 Å, are coordinated to the pentadentate bisoxazoline-imidazole moiety and are bridged by the central phenoxy group in addition to a hydroxide ligand. Ligand 7 forms complex binuclear complexes with ZnCl2 and NiCl2 involving two metal centers and three ligand units. The 2:3 ZnCl2/7 complex crystal structure exhibits a Zn∙∙∙Zn distance of 3.056 Å. Compound 8a forms 2:2 complexes with ZnCl2 and NiCl2, whereas 8b was reported to form a bis-palladium complex with one equivalent of [(η3-C3H3)PdCl]2 [51]. Little is known about the complexing abilities of compounds 9 and 11 [49,52]. The naphthyridine-based ligand 10 forms a dinuclear complex with nickel(ΙΙ) acetate (Ni∙∙∙Ni distance = 3.132 Å). Compound 12, possessing an urea backbone, forms a bis-copper complex with two equivalents of CuCl2 (Cu∙∙∙Cu distance = 4.291 Å) [53]. Tetraoxazoline ligand 13 undergoes formation of dinuclear complexes upon treatment with two equivalents of either ZnCl2, Ni(PPh3)2Br2, or Cu(OAc)2 (metal distances: Zn∙∙∙Zn = 8.963 Å; Ni∙∙∙Ni = 11.341 Å; Cu∙∙∙Cu = 9.432 Å) [54].

Figure 2: Previously reported bisoxazoline ligands capable of stabilizing bimetallic complexes.

Figure 2: Previously reported bisoxazoline ligands capable of stabilizing bimetallic complexes.

Results and Discussion

A number of bisoxazoline ligands with different bridging units were designed. We rationalized that the presence of three binding sites per metal center would be ideal in order to achieve the desired 1:2 ligand to metal ratio, and to prevent the potential formation of 2:2 or other higher order complexes. Variation of the bridging moiety should allow for modulation of the distance between the metal centers. An important criterion for selecting bridging units was their known ability to engage in metal-binding, along with being readily available. This led to the selection of naphthyridine, pyridazine, pyrazole, and phenol building blocks. We opted to connect these linkers to oxazolines via amide bonds. The reasoning for this was twofold. Firstly, this should provide ligands with significantly improved stabilities over for instance imine linkers. In addition, each amide moiety, upon deprotonation (a requirement for complex formation), would provide a formal negative charge on the ligand, thus resulting in increased complex stability while reducing the number of spectator anions associated with the two metals. Different combinations of five- and six-membered chelate rings were considered, as those allow for further modulation of metal–metal distances. Convenient synthetic sequences were developed for six different ligands.

Naphthyridine-bridged bisoxazoline ligands. The synthesis of naphthyridine bridged bisoxazoline ligand 16-H2 is outlined in Scheme 1. 1,8-Naphthyridine-2,7-diacyl chloride 14, obtained via a known procedure from the corresponding diacid [49], was allowed to react with aminoindanol-derived aminophenyloxazoline 15 [55] to provide bisoxazoline ligand 16-H2 in 65% yield. Upon deprotonation, 16-H2 provides a dianionic ligand with three nitrogen donor atoms per metal center. Ligand 16-H2 was found to undergo complex formation with various copper, zinc, palladium and nickel salts.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of naphthyridine–bisoxazoline ligand 16-H2.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of naphthyridine–bisoxazoline ligand 16-H2.

Figure 3 shows the X-ray crystal structure of 16·Ni2(OAc)2, obtained from ligand 16-H2 and two equivalents of nickel(ΙΙ) acetate. The asymmetric unit of the crystal 16·Ni2(OAc)2 contains two nickel(ΙΙ) centers held in close proximity by three donor nitrogen atoms per metal center and two differently bridged acetate ions inside the coordination sphere. The nitrogen atoms on the naphthyridine and amide moieties bind to the nickel(ΙΙ) center to form a five-membered metallacycle, subtending N(2)–Ni(1)–N(3) and N(5)–Ni(2)–N(6) angles of 81.53° and 80.34°, respectively. Additionally, the nitrogen atoms on the oxazoline and amide moieties form six-membered rings with the nickel(ΙΙ) center with N(1)–Ni(1)–N(2) and N(4)–Ni(2)–N(5) angles of 93.03° and 90.24°, respectively. All of the Ni–N distances are between 2.003 and 2.129 Å, typical for complexes of this type [56,57]. Interestingly, while one of the two acetate ions bridge the two nickel(ΙΙ) centers by binding through the two oxygens, the second acetate unit has a somewhat different binding pattern: one oxygen binds to Ni(1) and the other oxygen acts as the bridge between Ni(1) and Ni(2). The Ni(1)∙∙∙Ni(2) distance is 3.448 Å, which is slightly longer than the corresponding Ni∙∙∙Ni distance in the structurally related 10. The sixth coordination of Ni(2) is fulfilled by the amide oxygen of a second molecule of the complex (not shown in the figure for clarity). Apparently, the coordination environment involving three O-atoms from acetate groups (the Ni(1) situation) for one of the two metals is preferred in 16·Ni2(OAc)2, presumably for steric reasons, as crystal packing motivations would likely favor two situations as found for Ni(2), and possibly favoring formation of the 1D polymeric chain found here extending along the crystal b-axis. When this interaction is taken into account, both the nickel(ΙΙ) centers are in distorted octahedral environment. Overall, the ligand backbone of complex 16·Ni2(OAc)2 shows a helical arrangement. This helicity is facilitated by the innate stereogenic centers of the oxazoline moieties which is further extended by the flexibility afforded by the amide connections.

![[1860-5397-14-175-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-14-175-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) of the molecular structure of 16·Ni2(OAc)2. Hydrogen and solvate atoms have been omitted for clarity: (A) view normal to the mean molecular plane; (B) side view nearly perpendicular to (A) to allow better view of the region of open access to the metal site. The complex 16·Ni2(OAc)2 crystallizes in the orthorhombic space group P212121 with a = 14.1829(5) Å, b = 14.8645(6) Å, c = 25.2342(10) Å, α = 90°, β = 90°, γ = 90°, V = 5319.9(4) Å3, Z = 4, Dc = 1.450 mg m−3 and μ(Mo Kα) = 1.017 mm−1.

Figure 3: Thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) of the molecular structure of 16·Ni2(OAc)2. Hydrogen and s...

Naphthyridine ligand 22-H2 was designed as an analogue of ligand 16-H2 that possesses a shortened amide bridge to allow for the formation of bimetallic complexes with all five-membered chelate rings. Ligand 22-H2 was obtained starting from glycinol 17 and N-carboxybenzyl glycine (20) via the sequence of steps outlined in Scheme 2. While X-ray quality crystals have not yet been obtained, preliminary experiments have shown that ligand 22-H2 undergoes complex formation with various nickel and palladium salts [58].

Scheme 2: Synthesis of naphthyridine–bisoxazoline ligand 22-H2.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of naphthyridine–bisoxazoline ligand 22-H2.

Pyrazole-bridged bisoxazoline ligands. The synthesis of an analog of bisoxazoline ligand 16-H2 in which the naphthyridine bridge is replaced with a pyrazole linker is shown in Scheme 3. In addition to the change in geometry, compound 25-H3 is a potentially trianionic as opposed to a dianionic ligand. A reaction of pyrazole-3,5-diacyl chloride 23, obtained by treatment of pyrazol-3,5-dicarboxylic acid with thionyl chloride, with aminophenyloxazoline 24 [59] provided ligand 25-H3 in 85% yield.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of pyrazole–bisoxazoline ligand 25-H3.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of pyrazole–bisoxazoline ligand 25-H3.

Treatment of 25-H3 with nickel(II) acetate provided the binuclear complex 25·Ni2(OAc), the X-ray structure of which is shown in Figure 4. Each unit of the complex is comprised of two nickel(II) centers, each bound by three nitrogen atoms from the ligand skeleton and bridged by an acetate anion. The nitrogen atoms from pyrazole and amide moieties coordinate to the two nickel centers to form five-membered metallacycles, subtending N(1)–Ni(1)–N(2) and N(4)–Ni(2)–N(5) angles of 84.0° and 85.0°, respectively. Similarly, the nitrogen atoms on amide and oxazoline moieties form six-membered metallacyles with the two metal centers, with N(2)–Ni(1)–N(3) and N(5)–Ni(2)–N(6) angles of 92.63° and 94.33°, respectively. All the Ni–N distances are between 1.855 and 1.903 Å, typical for Ni–N bonds having this coordination geometry. The two nickel centers are bridged by an acetate ion and the pyrazole segment of the ligand, with a distorted square planar geometry observed for both metal centers. The resulting Ni(1)∙∙∙Ni(2) distance is 4.176 Å.

![[1860-5397-14-175-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-14-175-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) of the molecular structure of 25·Ni2(OAc). Hydrogen and solvate atoms have been omitted for clarity: (A) view normal to the mean molecular plane; (B) side view nearly perpendicular to (A) to allow better view of the region of open access to the metal site. The complex 25·Ni2(OAc) crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21 with a = 9.0473(9) Å, b = 17.5433(17) Å, c = 11.7671(11) Å, α = 90°, β = 109.643(2)°, γ = 90°, V = 1759.0(3) Å3, Z = 2, Dc = 1.614 mg m−3 and μ(Mo Kα) = 1.281 mm−1.

Figure 4: Thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) of the molecular structure of 25·Ni2(OAc). Hydrogen and so...

The synthesis of a pyrazole containing ligand potentially capable of forming bimetallic complexes with all five-membered chelate rings is shown in Scheme 4. Trianionic ligand 30-H3 was prepared starting from the N-carboxybenzyl amino acid 26. Coupling of 26 with phenylglycinol (17) resulted in the formation of the amide 27. Subsequent treatment with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride and triethylamine in the presence of a catalytic amount of DMAP provided oxazoline 28. Following deprotection, the resulting amine 29 was allowed to react with half an equivalent of the pyrazole diacyl chloride 23 to yield the pyrazole-bridged bisoxazoline ligand 30-H3.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of pyrazole–bisoxazoline ligand 30-H3.

Scheme 4: Synthesis of pyrazole–bisoxazoline ligand 30-H3.

Initial experiments have shown that the trianionic ligand 30-H3 readily forms complexes with various nickel, copper and palladium salts. Figure 5 shows the X-ray crystal structure of 30·Pd2Br, obtained from ligand 30-H3 and two equivalents of palladium(ΙΙ) bromide. Each of the two palladium(ΙΙ) centers of the complex 30·Pd2Br is confined in a slightly distorted square planar geometry by three donor nitrogen atoms from the ligand and a bridging bromide ion. Unlike the situation in 16·Ni2(OAc)2, where the Ni–O bond from the carbonyl of an adjacent molecule yields both the five-coordinate Ni and 1D polymeric chain, there are no Pd–O bonds (not even dative) in 30·Pd2Br and the Pd atoms remain nearly square planar. The donor nitrogen atoms from pyrazole, amide and oxazoline moieties coordinate to the palladium centers, forming five-membered chelate rings, with the subtended N–Pd–N angles ranging from 79.43° to 82.16°. The two palladium centers are bridged by the bromide ion and the pyrazole segment. All of the Pd–N bond lengths fall within a relatively narrow range of 1.925 to 2.025 Å, and are typical for Pd–N bonds with this coordination geometry. As expected, the Pd–Br bond lengths are slightly longer (2.519 and 2.529 Å) than the Pd–N bonds. The bromide ion bridges the two palladium centers with a Pd–Br–Pd angle of 98.48°. The two nitrogen donor atoms from the pyrazole moiety forms the second bridging link between the two metal centers, thereby restricting the N(1)–Pd(1)–Br(1) and N(4)–Pd(2)–Br(1) angles to 89.89° and 89.73°, respectively. The resulting Pd(1)∙∙∙Pd(2) distance was observed to be 3.824 Å.

![[1860-5397-14-175-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-14-175-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: Thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) of the molecular structure of 30·Pd2Br. Hydrogen and solvate atoms have been omitted for clarity: (A) view normal to the mean molecular plane; (B) side view nearly perpendicular to (A) to allow a better view of the region of open access to the metal site. The complex 30·Pd2Br crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21 with a = 9.8982(7) Å, b = 10.0139(7) Å, c = 16.9675(12) Å, α = 90°, β = 101.277(1)°, γ = 90°, V = 1649.3(2) Å3, Z = 2, Dc = 1.847 mg m−3 and μ(Mo Kα) = 2.510 mm−1.

Figure 5: Thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) of the molecular structure of 30·Pd2Br. Hydrogen and solva...

Pyridazine-bridged bisoxazoline ligands. Ligand 32-H2 was synthesized from pyridazine diester 31 [60] and aminophenyloxazoline 15 (Scheme 5). Treatment of 15 with LDA, followed by addition of 31, resulted in the formation of the pyridazine bridged bisoxazoline ligand 32-H2.

Scheme 5: Synthesis of pyridazine–bisoxazoline ligand 32-H2.

Scheme 5: Synthesis of pyridazine–bisoxazoline ligand 32-H2.

Upon deprotonation, 32-H2 provides a dianionic ligand with three donor nitrogen atoms per metal center. Ligand 32-H2 forms complexes with different nickel, copper, zinc and palladium salts. Shown in Figure 6 is the molecular structure of 32·Zn2Cl2. Each unit of the complex 32·Zn2Cl2 consists of two zinc(ΙΙ) centers, with each bound by three donor nitrogen atoms from the ligand skeleton and bridged by a chloride ion. The nitrogen atoms on the pyridazine and amide moieties form five-membered chelate rings upon coordination to the zinc centers, subtending N(2)–Zn(1)–N(1) and N(5)–Zn(2)–N(4) angles of 74.74° and 77.04°, respectively. The coordination of the nitrogen atoms on oxazoline and amide moieties with the two zinc centers forms six-membered rings with N(3)–Zn(1)–N(2) and N(6)–Zn(2)–N(5) angles of 87.05° and 88.55°, respectively. All of the Zn–N distances are within 2.023–2.177 Å, as expected for such complexes. Interestingly, the two chloride ions bind in discrete manners. While one of them acts as a bridge between the two zinc centers with a Zn(1)–Cl(1)–Zn(2) angle of 105.97°, the other chloride ion binds to Zn(2) only with a Zn(2)–Cl(2) distance of 2.241 Å. Consistent with having a bridging chloride atom, the Zn(1)∙∙∙Zn(2) distance of 3.857 Å is somewhat long, compared to the M∙∙∙M distances in two of the crystal structures mentioned here, namely, the Ni∙∙∙Ni in 16·Ni2(OAc)2 at 3.338 Å, shorter because of the smaller radius of the bridging μ2-O atom, and the 30·Pd2Br at 3.824 Å, shorter because of both the Pd coordination geometry and the bridging μ2-Br atom. The Ni∙∙∙Ni in 25·Ni2(OAc) at 4.176 Å is longer due to its longer three-atom bridge from OAc. In the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), there are ten instances of Ni–N–N–Ni bond connectivity with sp2 N-atoms that are also bonded to a C-atom. However, all of those have trans related Ni atoms unlike the cis related here such that the Ni∙∙∙Ni distances range from 4.54 to 4.72 Å for those ten compounds. Similarly, for Pd–N–N–Pd and Zn–N–N–Zn, there are few and only all trans situations in the CSD with ranges of 4.83 to 4.84 Å and 4.53 to 4.78 Å, respectively, for the two Pd and three Zn compounds. For M–N–N–M with sp3 bridging N-atoms, only four instances are found – all with M = Zn and N–N from substituted aminohydrazido ligands and the distances are longer (4.93 to 5.04 Å) and the trans relationship maintains. Thus, the cis M–N–N–M geometry observed here is quite rare for M = Ni, Zn, Pd and is uncommon for M = any transition metal (about 90 instances in CSD). Different coordination environments are found for Zn(1) and Zn(2) in 32·Zn2Cl2. Zn(1) is found to exist in a square planar environment that experiences a significant tetrahedral distortion. In contrast, a distorted square pyramidal binding mode is observed for Zn(2).

![[1860-5397-14-175-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-14-175-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) of the molecular structure of 32·Zn2Cl2. Hydrogen and solvate atoms have been omitted for clarity: (A) view normal to the mean molecular plane; (B) side view nearly perpendicular to (A) to allow better view of the region of open access to the metal site. The complex 32·Zn2Cl2 crystallizes in the monoclinic space group C2 with a = 40.820(5) Å, b = 7.4084(9) Å, c = 14.6489(17) Å, α = 90°, β = 108.589(2)°, γ = 90°, V = 4189.8(9) Å3, Z = 4, Dc = 1.575 mg m−3 and μ(Mo Kα) = 1.453 mm−1.

Figure 6: Thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) of the molecular structure of 32·Zn2Cl2. Hydrogen and solv...

Phenol-bridged bisoxazoline ligands. Ligands incorporating naphthyridine, pyridazine and pyrazole linkers discussed thus far bridge two metal atoms by attachment to two different nitrogen donor atoms. As a result, metal∙∙∙metal distances tend to be relatively long. Ligand 34-H3 was designed to explore the effect of a single atom linker, namely a phenoxy bridge. The tert-butyl group in the para-position was incorporated as it would likely increase the overall solubility of the ligand as well as its associated complexes. DCC-mediated coupling of 33 [49] with two equivalents of aminophenyloxazoline 15 led to the formation of phenol-bridged bisoxazoline ligand 34-H3 in a single step and moderate yield (Scheme 6). While X-ray quality crystals have not yet been obtained, preliminary experiments have shown that ligand 34-H2 forms complexes with nickel, copper and palladium salts [58].

Scheme 6: Synthesis of phenol–bisoxazoline ligand 34-H3.

Scheme 6: Synthesis of phenol–bisoxazoline ligand 34-H3.

Conclusion

We have achieved the synthesis of chiral bisoxazoline ligands that incorporate naphthyridine, pyrazole, pyridazine and phenol bridges. These compounds readily form complexes with various transition metal salts and may provide a platform for the development of new catalytic enantioselective transformations.

References

-

Johnson, J. S.; Evans, D. A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 325. doi:10.1021/ar960062n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McManus, H. A.; Guiry, P. J. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4151. doi:10.1021/cr040642v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Desimoni, G.; Faita, G.; Jorgensen, K. A. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3561. doi:10.1021/cr0505324

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vaugeois, J.; Simard, M.; Wuest, J. D. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1995, 145, 55. doi:10.1016/0010-8545(95)90216-3

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gavrilova, A. L.; Bosnich, B. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 349. doi:10.1021/cr020604g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibasaki, M.; Yamamoto, Y., Eds. Multimetallic Catalysts in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2004.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Mitić, N.; Smith, S. J.; Neves, A.; Guddat, L. W.; Gahan, L. R.; Schenk, G. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3338. doi:10.1021/cr050318f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karplus, P. A.; Pearson, M. A.; Hausinger, R. P. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997, 30, 330. doi:10.1021/ar960022j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stenkamp, R. E. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 715. doi:10.1021/cr00027a008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Whittington, D. A.; Lippard, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 827. doi:10.1021/ja003240n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Logan, D. T.; Su, X.-D.; Åberg, A.; Regnström, K.; Hajdu, J.; Eklund, H.; Nordlund, P. Structure 1996, 4, 1053. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00112-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gerdemann, C.; Eicken, C.; Krebs, B. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 183. doi:10.1021/ar990019a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kanyo, Z. F.; Scolnick, L. R.; Ash, D. E.; Christianson, D. W. Nature 1996, 383, 554. doi:10.1038/383554a0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibasaki, M.; Sasai, H.; Arai, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1237. doi:10.1002/anie.199712361

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shibasaki, M.; Kanai, M.; Matsunaga, S.; Kumagai, N. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1117. doi:10.1021/ar9000108

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Konsler, R. G.; Karl, J.; Jacobsen, E. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 10780. doi:10.1021/ja982683c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Ito, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 12003. doi:10.1021/ja003033n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Bartlett, M. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 688. doi:10.1021/ar500374r

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gao, J.; Reibenspies, J. H.; Martell, A. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 6008. doi:10.1002/anie.200351978

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gao, J.; Zingaro, R. A.; Reibenspies, J. H.; Martell, A. E. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2453. doi:10.1021/ol049156k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ooi, T.; Saito, A.; Maruoka, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 3745. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00575-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Keiji, M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 82, 917. doi:10.1246/bcsj.82.917

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sharma, V.; Simard, M.; Wuest, J. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 7931. doi:10.1021/ja00046a061

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vaugeois, J.; Wuest, J. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 13016. doi:10.1021/ja982725x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wuest, J. D. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999, 32, 81. doi:10.1021/ar980076o

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Constable, E. C.; Zhang, G.; Housecroft, C. E.; Neuburger, M.; Schaffner, S.; Woggon, W.-D. New J. Chem. 2009, 33, 1064. doi:10.1039/b821995h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tschinkl, M.; Schier, A.; Riede, J.; Gabbai, F. P. Organometallics 1999, 18, 1747. doi:10.1021/om990144q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guo, Q.-X.; Wu, Z.-J.; Luo, Z.-B.; Liu, Q.-Z.; Ye, J.-L.; Luo, S.-W.; Cun, L.-F.; Gong, L.-Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13927. doi:10.1021/ja074322f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, J.; Lang, K.; Abboud, K. A.; Hong, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16484. doi:10.1021/ja807221s

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, W.; Thakur, S. S.; Chen, S.-W.; Shin, C.-K.; Kawthekar, R. B.; Kim, G.-J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 3453. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.03.042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kawthekar, R. B.; Kim, G.-J. Helv. Chim. Acta 2008, 91, 317. doi:10.1002/hlca.200890037

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Annamalai, V.; DiMauro, E. F.; Carroll, P. J.; Kozlowski, M. C. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 1973. doi:10.1021/jo025993t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prokofieva, A.; Dechert, S.; Grosse, C.; Sheldrick, G. M.; Meyer, F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 4994. doi:10.1002/chem.200900424

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oh, T.; Lopez, P.; Reilly, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 2901. doi:10.1002/1099-0690(200008)2000:16<2901::AID-EJOC2901>3.0.CO;2-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reilly, M.; Oh, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 221. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(94)02227-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jammi, S.; Saha, P.; Sanyashi, S.; Sakthivel, S.; Punniyamurthy, T. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 11724. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Keller, F.; Rippert, A. J. Helv. Chim. Acta 1999, 82, 125. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1522-2675(19990113)82:1<125::AID-HLCA125>3.0.CO;2-W

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takizawa, S.; Katayama, T.; Sasai, H. Chem. Commun. 2008, 4113. doi:10.1039/b806016a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takizawa, S.; Katayama, T.; Somei, H.; Asano, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kameyama, C.; Rajesh, D.; Onitsuka, K.; Suzuki, T.; Mikami, M.; Yamataka, H.; Jayaprakash, D.; Sasai, H. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 3361. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.01.110

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Saito, A.; Yanai, H.; Taguchi, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 9439. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.10.079

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Saito, A.; Ito, H.; Taguchi, T. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4619. doi:10.1021/ol026963f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kleinbeck, F.; Toste, F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9178. doi:10.1021/ja904055z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, D.; Yuan, Y.; Chan, A. S. C.; Wang, R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 2738. doi:10.1002/chem.200802688

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, J.; Yang, M.; Yuan, F.; Jia, X.; Yang, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, C. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 920. doi:10.1002/adsc.200800767

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, J.; Yuan, F.; Yang, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 548. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.11.060

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sakaguchi, S.; Yoo, K. S.; O'Neil, J.; Lee, J. H.; Stewart, T.; Jung, K. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9326. doi:10.1002/anie.200803793

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4566. doi:10.1002/anie.200300635

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, J.; Hong, S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6931. doi:10.1039/c2cs35129c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fahrni, C. J.; Pfaltz, A. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 491. doi:10.1002/hlca.19980810304

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Fahrni, C. J.; Pfaltz, A.; Neuburger, M.; Zehnder, M. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 507. doi:10.1002/hlca.19980810305

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tsukada, N.; Sato, T.; Mori, H.; Sugawara, S.; Kabuto, C.; Miyano, S.; Inoue, Y. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 627, 121. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(01)00729-X

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seitz, M.; Kaiser, A.; Tereshchenko, A.; Geiger, C.; Uematsu, Y.; Reiser, O. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 9973. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.08.003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mal, R.; Mittal, N.; Emge, T. J.; Seidel, D. Chem. Commun. 2009, 7309. doi:10.1039/b918735a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nano, A.; Brelot, L.; Rogez, G.; Maisse-François, A.; Bellemin-Laponnaz, S. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2011, 376, 285. doi:10.1016/j.ica.2011.06.029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Doherty, S.; Knight, J. G.; McRae, A.; Harrington, R. W.; Clegg, W. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 1759. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200700922

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Allen, F. H. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 2002, 58, 380. doi:10.1107/S0108768102003890

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Groom, C. R.; Bruno, I. J.; Lightfoot, M. P.; Ward, S. C. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171. doi:10.1107/S2052520616003954

Return to citation in text: [1] -

In preliminary studies regarding complex formation, metal salts were mixed with the ligand in a 2:1 ratio in dichloromethane. While the metal salts were essentially insoluble in dichloromethane, nearly homogeneous solutions resulted after stirring. Following filtration and removal of solvents, brightly colored solids were obtained as opposed to white/colorless ligands.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wolińska, E. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 1478. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2014.10.001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bessard, Y.; Crettaz, R.; Brieden, W. Method of producing pyridazine-3,6-dicarboxylic esters. WO Pat. Appl. WO2001007415A1, Feb 1, 2001.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 58. | In preliminary studies regarding complex formation, metal salts were mixed with the ligand in a 2:1 ratio in dichloromethane. While the metal salts were essentially insoluble in dichloromethane, nearly homogeneous solutions resulted after stirring. Following filtration and removal of solvents, brightly colored solids were obtained as opposed to white/colorless ligands. |

| 59. | Wolińska, E. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 1478. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2014.10.001 |

| 60. | Bessard, Y.; Crettaz, R.; Brieden, W. Method of producing pyridazine-3,6-dicarboxylic esters. WO Pat. Appl. WO2001007415A1, Feb 1, 2001. |

| 1. | Johnson, J. S.; Evans, D. A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 325. doi:10.1021/ar960062n |

| 2. | McManus, H. A.; Guiry, P. J. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4151. doi:10.1021/cr040642v |

| 3. | Desimoni, G.; Faita, G.; Jorgensen, K. A. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3561. doi:10.1021/cr0505324 |

| 19. | Gao, J.; Reibenspies, J. H.; Martell, A. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 6008. doi:10.1002/anie.200351978 |

| 20. | Gao, J.; Zingaro, R. A.; Reibenspies, J. H.; Martell, A. E. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2453. doi:10.1021/ol049156k |

| 8. | Karplus, P. A.; Pearson, M. A.; Hausinger, R. P. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997, 30, 330. doi:10.1021/ar960022j |

| 21. | Ooi, T.; Saito, A.; Maruoka, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 3745. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00575-9 |

| 22. | Keiji, M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 82, 917. doi:10.1246/bcsj.82.917 |

| 7. | Mitić, N.; Smith, S. J.; Neves, A.; Guddat, L. W.; Gahan, L. R.; Schenk, G. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3338. doi:10.1021/cr050318f |

| 17. | Trost, B. M.; Ito, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 12003. doi:10.1021/ja003033n |

| 18. | Trost, B. M.; Bartlett, M. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 688. doi:10.1021/ar500374r |

| 4. | Vaugeois, J.; Simard, M.; Wuest, J. D. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1995, 145, 55. doi:10.1016/0010-8545(95)90216-3 |

| 5. | Gavrilova, A. L.; Bosnich, B. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 349. doi:10.1021/cr020604g |

| 6. | Shibasaki, M.; Yamamoto, Y., Eds. Multimetallic Catalysts in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2004. |

| 18. | Trost, B. M.; Bartlett, M. J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 688. doi:10.1021/ar500374r |

| 13. | Kanyo, Z. F.; Scolnick, L. R.; Ash, D. E.; Christianson, D. W. Nature 1996, 383, 554. doi:10.1038/383554a0 |

| 14. | Shibasaki, M.; Sasai, H.; Arai, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1237. doi:10.1002/anie.199712361 |

| 15. | Shibasaki, M.; Kanai, M.; Matsunaga, S.; Kumagai, N. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1117. doi:10.1021/ar9000108 |

| 12. | Gerdemann, C.; Eicken, C.; Krebs, B. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 183. doi:10.1021/ar990019a |

| 16. | Konsler, R. G.; Karl, J.; Jacobsen, E. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 10780. doi:10.1021/ja982683c |

| 11. | Logan, D. T.; Su, X.-D.; Åberg, A.; Regnström, K.; Hajdu, J.; Eklund, H.; Nordlund, P. Structure 1996, 4, 1053. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00112-8 |

| 49. | Fahrni, C. J.; Pfaltz, A. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 491. doi:10.1002/hlca.19980810304 |

| 10. | Whittington, D. A.; Lippard, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 827. doi:10.1021/ja003240n |

| 6. | Shibasaki, M.; Yamamoto, Y., Eds. Multimetallic Catalysts in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2004. |

| 58. | In preliminary studies regarding complex formation, metal salts were mixed with the ligand in a 2:1 ratio in dichloromethane. While the metal salts were essentially insoluble in dichloromethane, nearly homogeneous solutions resulted after stirring. Following filtration and removal of solvents, brightly colored solids were obtained as opposed to white/colorless ligands. |

| 47. | Ma, J.-A.; Cahard, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4566. doi:10.1002/anie.200300635 |

| 48. | Park, J.; Hong, S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6931. doi:10.1039/c2cs35129c |

| 4. | Vaugeois, J.; Simard, M.; Wuest, J. D. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1995, 145, 55. doi:10.1016/0010-8545(95)90216-3 |

| 23. | Sharma, V.; Simard, M.; Wuest, J. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 7931. doi:10.1021/ja00046a061 |

| 24. | Vaugeois, J.; Wuest, J. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 13016. doi:10.1021/ja982725x |

| 25. | Wuest, J. D. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999, 32, 81. doi:10.1021/ar980076o |

| 26. | Constable, E. C.; Zhang, G.; Housecroft, C. E.; Neuburger, M.; Schaffner, S.; Woggon, W.-D. New J. Chem. 2009, 33, 1064. doi:10.1039/b821995h |

| 27. | Tschinkl, M.; Schier, A.; Riede, J.; Gabbai, F. P. Organometallics 1999, 18, 1747. doi:10.1021/om990144q |

| 28. | Guo, Q.-X.; Wu, Z.-J.; Luo, Z.-B.; Liu, Q.-Z.; Ye, J.-L.; Luo, S.-W.; Cun, L.-F.; Gong, L.-Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13927. doi:10.1021/ja074322f |

| 29. | Park, J.; Lang, K.; Abboud, K. A.; Hong, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16484. doi:10.1021/ja807221s |

| 30. | Li, W.; Thakur, S. S.; Chen, S.-W.; Shin, C.-K.; Kawthekar, R. B.; Kim, G.-J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 3453. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.03.042 |

| 31. | Kawthekar, R. B.; Kim, G.-J. Helv. Chim. Acta 2008, 91, 317. doi:10.1002/hlca.200890037 |

| 32. | Annamalai, V.; DiMauro, E. F.; Carroll, P. J.; Kozlowski, M. C. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 1973. doi:10.1021/jo025993t |

| 33. | Prokofieva, A.; Dechert, S.; Grosse, C.; Sheldrick, G. M.; Meyer, F. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 4994. doi:10.1002/chem.200900424 |

| 34. | Oh, T.; Lopez, P.; Reilly, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 2901. doi:10.1002/1099-0690(200008)2000:16<2901::AID-EJOC2901>3.0.CO;2-0 |

| 35. | Reilly, M.; Oh, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 221. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(94)02227-3 |

| 36. | Jammi, S.; Saha, P.; Sanyashi, S.; Sakthivel, S.; Punniyamurthy, T. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 11724. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.009 |

| 37. | Keller, F.; Rippert, A. J. Helv. Chim. Acta 1999, 82, 125. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1522-2675(19990113)82:1<125::AID-HLCA125>3.0.CO;2-W |

| 38. | Takizawa, S.; Katayama, T.; Sasai, H. Chem. Commun. 2008, 4113. doi:10.1039/b806016a |

| 39. | Takizawa, S.; Katayama, T.; Somei, H.; Asano, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kameyama, C.; Rajesh, D.; Onitsuka, K.; Suzuki, T.; Mikami, M.; Yamataka, H.; Jayaprakash, D.; Sasai, H. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 3361. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.01.110 |

| 40. | Saito, A.; Yanai, H.; Taguchi, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 9439. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.10.079 |

| 41. | Saito, A.; Ito, H.; Taguchi, T. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4619. doi:10.1021/ol026963f |

| 42. | Kleinbeck, F.; Toste, F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9178. doi:10.1021/ja904055z |

| 43. | Zhao, D.; Yuan, Y.; Chan, A. S. C.; Wang, R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 2738. doi:10.1002/chem.200802688 |

| 44. | Sun, J.; Yang, M.; Yuan, F.; Jia, X.; Yang, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, C. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 920. doi:10.1002/adsc.200800767 |

| 45. | Sun, J.; Yuan, F.; Yang, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 548. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.11.060 |

| 46. | Sakaguchi, S.; Yoo, K. S.; O'Neil, J.; Lee, J. H.; Stewart, T.; Jung, K. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9326. doi:10.1002/anie.200803793 |

| 55. | Doherty, S.; Knight, J. G.; McRae, A.; Harrington, R. W.; Clegg, W. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 1759. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200700922 |

| 56. | Allen, F. H. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 2002, 58, 380. doi:10.1107/S0108768102003890 |

| 57. | Groom, C. R.; Bruno, I. J.; Lightfoot, M. P.; Ward, S. C. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171. doi:10.1107/S2052520616003954 |

| 54. | Nano, A.; Brelot, L.; Rogez, G.; Maisse-François, A.; Bellemin-Laponnaz, S. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2011, 376, 285. doi:10.1016/j.ica.2011.06.029 |

| 49. | Fahrni, C. J.; Pfaltz, A. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 491. doi:10.1002/hlca.19980810304 |

| 49. | Fahrni, C. J.; Pfaltz, A. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 491. doi:10.1002/hlca.19980810304 |

| 52. | Seitz, M.; Kaiser, A.; Tereshchenko, A.; Geiger, C.; Uematsu, Y.; Reiser, O. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 9973. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.08.003 |

| 53. | Mal, R.; Mittal, N.; Emge, T. J.; Seidel, D. Chem. Commun. 2009, 7309. doi:10.1039/b918735a |

| 49. | Fahrni, C. J.; Pfaltz, A. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 491. doi:10.1002/hlca.19980810304 |

| 50. | Fahrni, C. J.; Pfaltz, A.; Neuburger, M.; Zehnder, M. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 507. doi:10.1002/hlca.19980810305 |

| 51. | Tsukada, N.; Sato, T.; Mori, H.; Sugawara, S.; Kabuto, C.; Miyano, S.; Inoue, Y. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 627, 121. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(01)00729-X |

© 2018 Das et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)