Abstract

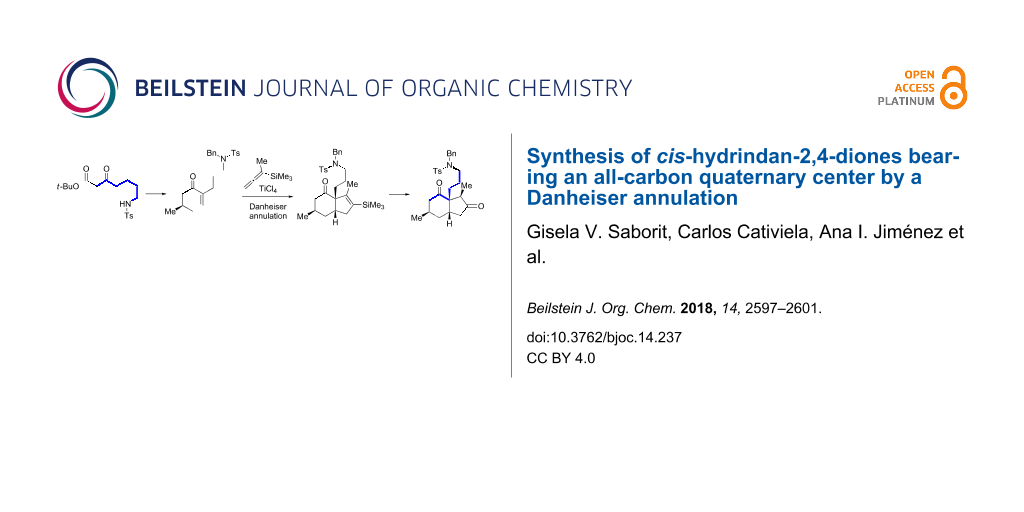

A straightforward synthetic entry to functionalized hydrindane compounds based on a rapid assembly of the core nucleus by a Danheiser cycloaddition is reported. Valuable bicyclic building blocks containing the fused five and six-membered carbocyclic ring system can be achieved in only four steps from a simple acyclic β-keto ester.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

cis-Fused hydrindanes (bicyclo[4.3.0]nonanes) [1,2], scaffolds of numerous natural products, are amenable to application as advanced intermediates in the total synthesis of Lycopodium alkaloids [3-6], 3a-substituted 2,4-dicarbonyl compounds being particularly useful in this field. The synthetic approaches toward these versatile building blocks (i.e., compounds with the functionalization pattern A) are outlined in Figure 1, which for the sake of clarity omits the substituents not involved in the bond-forming step in the final ring closure. Almost all the strategies developed to date involve the formation of the C3–C3a bond in the ring-closing step leading to the hydrindane nucleus. The carbocyclization takes place from polyfunctionalized cyclohexanones or related compounds through a Michael reaction [7], successive inter- and intramolecular radical processes [8], intramolecular carbene addition/cyclization [9,10], aldol cyclizations either under Lewis acid catalysis [11] or from diazoketones in the presence of bases (e.g., DBU) [12], Pd-catalyzed cycloalkenylation of a silyl enol ether [13], or base-promoted ynone carbocyclizations [14,15]. Another approach through an aldol cyclization, forming the C1–C7a bond instead, has also been reported [16]. Different strategies were developed by Overman through ring-expanding cyclopentane annulations based on a Prins–pinacol rearrangement [17,18] and Au(I)-catalyzed pinacol-terminated 1,6-enyne cyclizations [19,20], the C3a–C7a bond formation occurring in the last step of both procedures. Finally, Snyder gained access to the type A hydrindane nucleus from an acyclic compound by a cascade radical process using Mn(OAc)3 [21], although a trans-fused ring system was formed. Also of note, is the approach of Mori [22] to a dihydroindenedione based on an initial cyclization of an allyl iodide in a 1,3-cyclohexanedione side chain via an allyl anion (generated by Me3SiSnBu3 and CsF).

Figure 1: Previous synthetic approaches to 3a-substituted cis-hydrindan-2,4-diones.

Figure 1: Previous synthetic approaches to 3a-substituted cis-hydrindan-2,4-diones.

As a continuation of our work on the synthesis of Lycopodium alkaloids [23-26], we hypothesized that decahydroquinoline 1, a versatile building block for the synthesis of phlegmarine-type alkaloids, available in both enantiomeric forms, could also serve as an intermediate toward other Lycopodium alkaloids (e.g., fawcettimine). Thus, we surmised that building block 1 could be a new precursor of 3a-substituted hydrindan-2,4-diones (Scheme 1). This type of compounds, when adequately functionalized, has been used as advanced intermediates for the synthesis of the Lycopodium alkaloids carinatine A [11,14,15], 8-deoxyserratinine [10], fawcettidine [10], fawcettimine [7,10], lycojaponicumin C [10], lycopladine A [11,13-15], lycoposerramine R [13,14], and sieboldine [19,20] (Figure 2).

Scheme 1: Decahydroquinoline 1 as a versatile building block for Lycopodium alkaloid synthesis.

Scheme 1: Decahydroquinoline 1 as a versatile building block for Lycopodium alkaloid synthesis.

Figure 2: Examples of Lycopodium alkaloids synthesized from 3a-substituted hydrindan-2,4-diones.

Figure 2: Examples of Lycopodium alkaloids synthesized from 3a-substituted hydrindan-2,4-diones.

Results and Discussion

Despite the potential of [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions [27] to achieve cis-hydrindan-2,4-diones, their application to rapidly assemble the five-membered ring of the targeted 6,5-bicylic system has not been reported until now. Two examples using cycloaddition processes in this field should be mentioned: Diels–Alder [28] and Pauson–Khand [29] reactions have been used to build the hydrindane bicyclic system, but incorporating a different functionalization pattern in the cyclic compounds.

Proposed here is a new methodological approach to functionalized 3a-substituted hydrindane synthesis based on a Danheiser annulation involving a [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of a (trimethylsilyl)allene and a suitable cyclic α,β-unsaturated ketone [30,31]. Despite the applicability of the reaction to construct five-membered rings, it has not been extensively examined [32] for the synthesis of complex natural products.

As depicted in Scheme 2, the hydrindane core ring would be assembled by the simultaneous formation of two C–C bonds. This strategy is based on the disconnection across the C1–C7a and C3–C3a bonds, which according to the Danheiser annulation logic would reveal the cyclohexenone intermediate I and a silylallene such as II. The former, in turn, would disconnect back to β-keto ester 1 (Scheme 1), which we have employed in the synthesis of phlegmarine-type Lycopodium alkaloids [23-26].

Scheme 2: A de novo approach to 3a-substituted cis-hydrindan-2,4-diones.

Scheme 2: A de novo approach to 3a-substituted cis-hydrindan-2,4-diones.

To prepare the starting material to evaluate the key Danheiser annulation reaction (Scheme 3), β-keto ester 2 was treated with crotonaldehyde and LiOH in iPrOH, following our previously developed procedure, to give decahydroquinoline 1 [23]. The removal of the tert-butyl ester group with TFA, followed by treatment with LiOH in refluxing THF promoted a retro-aza-Michael reaction yielding the ring-opened product 3 [33]. The latter was trapped in situ with benzyl bromide to furnish cyclohexenone 4 in 86% overall yield over the two steps from 1. Additionally, the overall transformation from the starting material 2 was also performed in a one-pot sequence involving six reactions, namely, an intermolecular Michael reaction, aldol cyclization, intramolecular aza-Michael reaction, removal of a tert-butoxycarbonyl ester, base-promoted ring opening and tosylamide benzylation, without significant detrimental effect on the overall yield (see Supporting Information File 1).

Scheme 3: Synthesis of enone 4 and the Danheiser annulation. The depicted compounds are all racemic.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of enone 4 and the Danheiser annulation. The depicted compounds are all racemic.

With the key precursor 4 in hand, the stage was set to study the Danheiser annulation step. Gratifyingly, treatment of 4 with TiCl4 in the presence of commercially available 1-methyl-1-(trimethylsilyl)allene at −78 °C for 1 h afforded the desired cis-6,5-bicylic core 5 in 63% yield as a single diastereomer. The desilylated product 6 was also obtained as a mixture of diastereomers. The high stereoselectivity of the ring-formation step can be explained by the suprafacial addition of the allene to the double bond of the α,β-unsaturated compound 4, the diastereoselectivity being sterically controlled by the methyl group on the β-face. The transformation of the vinylsilane moiety in 5 into the corresponding carbonyl group (Scheme 4) was carried out by a two-step procedure involving epoxidation of the vinylsilane 5, followed by a rearrangement of the diastereomeric mixture of epoxides 7 induced by formic acid [34,35]. The resulting ketone 8 was obtained as a 3.5:1 mixture of epimers at C3.

Scheme 4: Transformation of the vinylsilane moiety to ketone 8.

Scheme 4: Transformation of the vinylsilane moiety to ketone 8.

The relative configuration of the major epimer of 8 (Figure 3) was established on the basis of a cross peak in the NOESY spectrum that correlated the methyl group at C3 with a methylene proton adjacent to the quaternary carbon of the side chain at C3a. The configuration at C3, adjacent to a carbonyl group, is not relevant for the potential application of this type of building block (i.e., 8) in fawcettimine and related alkaloid synthesis, since this stereogenic center is epimerizable, as shown by Heathcock [7].

![[1860-5397-14-237-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-14-237-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Stereoview of cis-hydrindane 8.

Figure 3: Stereoview of cis-hydrindane 8.

Conclusion

In summary, we have successfully applied the Danheiser annulation reaction to rapidly assemble the 6,5-bicyclic nucleus of hydrindane compounds, expanding the usefulness of the versatile decahydroquinoline building block 1. Although the compounds were prepared in racemic form, optically active substances are also accessible from enantiopure 1 [23]. The overall sequence shows the potential of this strategy to achieve functionalized hydrindanes, which may be useful for the synthesis of Lycopodium alkaloids embodying the aforementioned bicyclic core.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures and copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of all compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.3 MB | Download |

References

-

Findley, T. J. K.; Sucunza, D.; Miller, L. C.; Helm, M. D.; Helliwell, M.; Davies, D. T.; Procter, D. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 2433–2451. doi:10.1039/c0ob01086c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, J.; Marsini, M. A.; Bedell, T. A.; Reider, P. J.; Sorensen, E. J. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 3713–3717. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2016.03.039

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, X.; Gang, D. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 752–772. doi:10.1039/b409720n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Siengalewicz, P.; Mulzer, J.; Rinner, U. Lycopodium alkaloids: synthetic highlights and recent developments. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Elsevier, 2013; Vol. 72, pp 1–151. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-407774-4.00001-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Murphy, R. A.; Sarpong, R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 42–56. doi:10.1002/chem.201303975

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Hong, B.; Ai, W.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Lei, X. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, No. 4614. doi:10.1038/ncomms5614

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Heathcock, C. H.; Blumenkopf, T. A.; Smith, K. M. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 1548–1562. doi:10.1021/jo00268a015

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Liu, K.-M.; Chau, C.-M.; Sha, C.-K. Chem. Commun. 2008, 91–93. doi:10.1039/B714078A

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Del Bel, M.; Rovira, A.; Guerrero, C. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12188–12191. doi:10.1021/ja4054866

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hou, S.-H.; Tu, Y.-Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.-M.; Wang, S.-H.; Zhang, X.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11373–11376. doi:10.1002/anie.201306369

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Meng, L. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7784–7789. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01435

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Li, Z.; Lam, S. M.; Ip, I.; Wong, W.-t.; Chiu, P. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4464–4467. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01963

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Qiu, F. G. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3598–3600. doi:10.1039/C8CC01626G

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Furukawa, T.; Trauner, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 893–896. doi:10.1002/anie.201610021

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Trauner, D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8206–8212. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00908

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Lei, S. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 11014–11020. doi:10.1039/c3ra41467a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hirst, G. C.; Howard, P. N.; Overman, L. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 1514–1515. doi:10.1021/ja00186a065

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Overman, L. E.; Wolfe, J. P. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 6421–6429. doi:10.1021/jo025927r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Canham, S. M.; France, D. J.; Overman, L. E. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9–34. doi:10.1021/jo300872y

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Canham, S. M.; France, D. J.; Overman, J. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 7876–7877. doi:10.1021/ja103666n

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Snider, B. B.; Buckman, B. O. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 322–326. doi:10.1021/jo00027a056

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kinoshita, A.; Mori, M. Chem. Lett. 1994, 1475–1478. doi:10.1246/cl.1994.1475

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Bonjoch, J. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 326–329. doi:10.1021/ol303257y

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Bonjoch, J. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 7099–7102. doi:10.1039/C4CC01708K

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bosch, C.; Fiser, B.; Gómez-Bengoa, E.; Bradshaw, B.; Bonjoch, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5084–5087. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02581

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Saborit, G. V.; Bosch, C.; Parella, T.; Bradshaw, B.; Bonjoch, J. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2629–2634. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00025

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

López, F.; Mascareñas, J. L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 418–428. doi:10.1002/chem.201002366

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zaimoku, H.; Taniguchi, T. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 9613–9619. doi:10.1002/chem.201403163

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Otsuka, Y.; Inagaki, F.; Mukai, C. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3420–3426. doi:10.1021/jo100499h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Danheiser, R. L.; Carini, D. J.; Basak, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 1604–1606. doi:10.1021/ja00396a071

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Danheiser, R. L.; Carini, D. J.; Fink, D. M.; Basak, A. Tetrahedron 1983, 39, 935–947. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88592-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Friese, J. C.; Krause, S.; Schäfer, H. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 2683–2685. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00402-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Saborit, G.; Cativiela, C.; Dorel, R.; Bo, C.; Bonjoch, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 13881–13892. doi:10.1002/chem.201301715

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Choi, J.-K.; Hart, D. J. Tetrahedron 1985, 41, 3959–3971. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)97176-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

May, T. L.; Dabrowski, J. A.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 736–739. doi:10.1021/ja110054q

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 32. | Friese, J. C.; Krause, S.; Schäfer, H. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 2683–2685. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00402-1 |

| 23. | Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Bonjoch, J. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 326–329. doi:10.1021/ol303257y |

| 24. | Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Bonjoch, J. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 7099–7102. doi:10.1039/C4CC01708K |

| 25. | Bosch, C.; Fiser, B.; Gómez-Bengoa, E.; Bradshaw, B.; Bonjoch, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5084–5087. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02581 |

| 26. | Saborit, G. V.; Bosch, C.; Parella, T.; Bradshaw, B.; Bonjoch, J. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2629–2634. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00025 |

| 23. | Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Bonjoch, J. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 326–329. doi:10.1021/ol303257y |

| 1. | Findley, T. J. K.; Sucunza, D.; Miller, L. C.; Helm, M. D.; Helliwell, M.; Davies, D. T.; Procter, D. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 2433–2451. doi:10.1039/c0ob01086c |

| 2. | Liu, J.; Marsini, M. A.; Bedell, T. A.; Reider, P. J.; Sorensen, E. J. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 3713–3717. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2016.03.039 |

| 9. | Del Bel, M.; Rovira, A.; Guerrero, C. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12188–12191. doi:10.1021/ja4054866 |

| 10. | Hou, S.-H.; Tu, Y.-Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.-M.; Wang, S.-H.; Zhang, X.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11373–11376. doi:10.1002/anie.201306369 |

| 23. | Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Bonjoch, J. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 326–329. doi:10.1021/ol303257y |

| 24. | Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Bonjoch, J. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 7099–7102. doi:10.1039/C4CC01708K |

| 25. | Bosch, C.; Fiser, B.; Gómez-Bengoa, E.; Bradshaw, B.; Bonjoch, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5084–5087. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02581 |

| 26. | Saborit, G. V.; Bosch, C.; Parella, T.; Bradshaw, B.; Bonjoch, J. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2629–2634. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b00025 |

| 8. | Liu, K.-M.; Chau, C.-M.; Sha, C.-K. Chem. Commun. 2008, 91–93. doi:10.1039/B714078A |

| 11. | Meng, L. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7784–7789. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01435 |

| 14. | Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Furukawa, T.; Trauner, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 893–896. doi:10.1002/anie.201610021 |

| 15. | Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Trauner, D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8206–8212. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00908 |

| 7. | Heathcock, C. H.; Blumenkopf, T. A.; Smith, K. M. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 1548–1562. doi:10.1021/jo00268a015 |

| 21. | Snider, B. B.; Buckman, B. O. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 322–326. doi:10.1021/jo00027a056 |

| 3. | Ma, X.; Gang, D. R. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 752–772. doi:10.1039/b409720n |

| 4. | Siengalewicz, P.; Mulzer, J.; Rinner, U. Lycopodium alkaloids: synthetic highlights and recent developments. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Elsevier, 2013; Vol. 72, pp 1–151. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-407774-4.00001-7 |

| 5. | Murphy, R. A.; Sarpong, R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 42–56. doi:10.1002/chem.201303975 |

| 6. | Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Hong, B.; Ai, W.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Lei, X. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, No. 4614. doi:10.1038/ncomms5614 |

| 22. | Kinoshita, A.; Mori, M. Chem. Lett. 1994, 1475–1478. doi:10.1246/cl.1994.1475 |

| 14. | Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Furukawa, T.; Trauner, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 893–896. doi:10.1002/anie.201610021 |

| 15. | Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Trauner, D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8206–8212. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00908 |

| 17. | Hirst, G. C.; Howard, P. N.; Overman, L. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 1514–1515. doi:10.1021/ja00186a065 |

| 18. | Overman, L. E.; Wolfe, J. P. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 6421–6429. doi:10.1021/jo025927r |

| 7. | Heathcock, C. H.; Blumenkopf, T. A.; Smith, K. M. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 1548–1562. doi:10.1021/jo00268a015 |

| 13. | Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Qiu, F. G. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3598–3600. doi:10.1039/C8CC01626G |

| 19. | Canham, S. M.; France, D. J.; Overman, L. E. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9–34. doi:10.1021/jo300872y |

| 20. | Canham, S. M.; France, D. J.; Overman, J. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 7876–7877. doi:10.1021/ja103666n |

| 23. | Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Bonjoch, J. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 326–329. doi:10.1021/ol303257y |

| 12. | Li, Z.; Lam, S. M.; Ip, I.; Wong, W.-t.; Chiu, P. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4464–4467. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01963 |

| 33. | Bradshaw, B.; Luque-Corredera, C.; Saborit, G.; Cativiela, C.; Dorel, R.; Bo, C.; Bonjoch, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 13881–13892. doi:10.1002/chem.201301715 |

| 34. | Choi, J.-K.; Hart, D. J. Tetrahedron 1985, 41, 3959–3971. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)97176-5 |

| 35. | May, T. L.; Dabrowski, J. A.; Hoveyda, A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 736–739. doi:10.1021/ja110054q |

| 7. | Heathcock, C. H.; Blumenkopf, T. A.; Smith, K. M. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 1548–1562. doi:10.1021/jo00268a015 |

| 10. | Hou, S.-H.; Tu, Y.-Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.-M.; Wang, S.-H.; Zhang, X.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11373–11376. doi:10.1002/anie.201306369 |

| 10. | Hou, S.-H.; Tu, Y.-Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.-M.; Wang, S.-H.; Zhang, X.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11373–11376. doi:10.1002/anie.201306369 |

| 10. | Hou, S.-H.; Tu, Y.-Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.-M.; Wang, S.-H.; Zhang, X.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11373–11376. doi:10.1002/anie.201306369 |

| 29. | Otsuka, Y.; Inagaki, F.; Mukai, C. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3420–3426. doi:10.1021/jo100499h |

| 30. | Danheiser, R. L.; Carini, D. J.; Basak, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 1604–1606. doi:10.1021/ja00396a071 |

| 31. | Danheiser, R. L.; Carini, D. J.; Fink, D. M.; Basak, A. Tetrahedron 1983, 39, 935–947. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88592-6 |

| 27. | López, F.; Mascareñas, J. L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 418–428. doi:10.1002/chem.201002366 |

| 28. | Zaimoku, H.; Taniguchi, T. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 9613–9619. doi:10.1002/chem.201403163 |

| 13. | Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Qiu, F. G. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3598–3600. doi:10.1039/C8CC01626G |

| 14. | Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Furukawa, T.; Trauner, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 893–896. doi:10.1002/anie.201610021 |

| 19. | Canham, S. M.; France, D. J.; Overman, L. E. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9–34. doi:10.1021/jo300872y |

| 20. | Canham, S. M.; France, D. J.; Overman, J. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 7876–7877. doi:10.1021/ja103666n |

| 10. | Hou, S.-H.; Tu, Y.-Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.-M.; Wang, S.-H.; Zhang, X.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11373–11376. doi:10.1002/anie.201306369 |

| 11. | Meng, L. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7784–7789. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01435 |

| 13. | Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Qiu, F. G. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3598–3600. doi:10.1039/C8CC01626G |

| 14. | Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Furukawa, T.; Trauner, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 893–896. doi:10.1002/anie.201610021 |

| 15. | Hartrampf, F. W. W.; Trauner, D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8206–8212. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00908 |

© 2018 Saborit et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)