Abstract

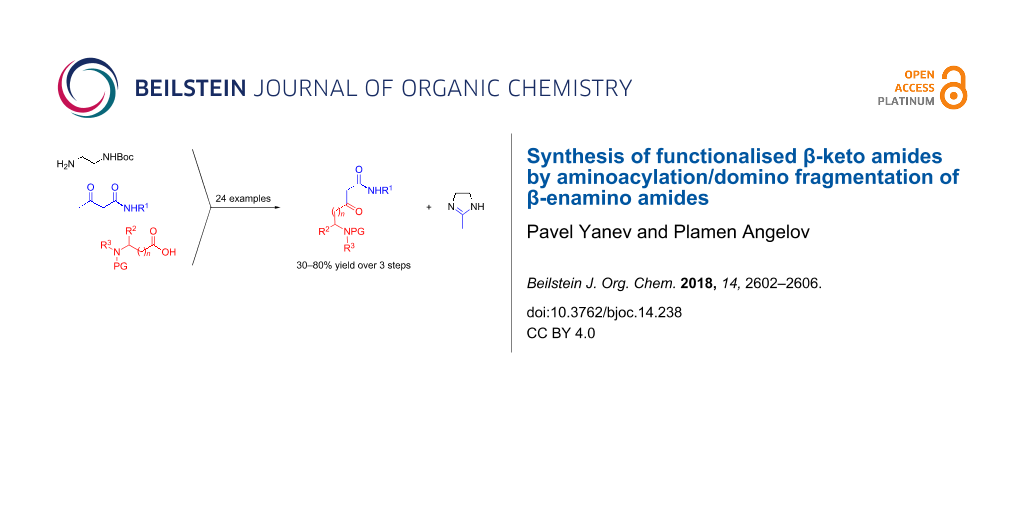

Ethylenediamine-derived β-enamino amides are used as equivalents of amide enolate synthons in C-acylation reactions with N-protected amino acids. Domino fragmentation of the obtained intermediates leads to functionalised β-keto amides, bearing a protected amino group in their side chain.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The acylation of amide enolates is one of the main synthetic approaches towards β-keto amides and has found numerous applications [1-9]. However, while the generation of tertiary amide enolates is straightforward, this is not the case with secondary and primary amides. The NH acidity of the latter compounds necessitates either a double deprotonation to ambident 1,3-dianions [10] or proper masking of the amide functionality prior to deprotonation [11,12]. Consequently, there are very few published reagents that are synthetically equivalent to primary or secondary amide enolate synthons. With regard to acylation reactions, maybe most important among these are some nitriles, which can be successfully acylated at the alpha position [13-15] and then hydrated [13,16-20] to reveal a primary amide functionality. The dianion of silylated acetamide is another such example, although with very limited scope [21]. A contribution of ours in this area is the application of ethylenediamine-derived β-enamino amides as synthetic equivalents of primary and secondary amide enolate synthons in reactions with acid chlorides [22]. To extend the scope of the methodology, we now have explored the acylation of these reagents with suitably activated amino acids, in order to prepare functionalised β-keto amides, bearing a protected amino group in their side chain. Keto amides of this type are excellent precursors to various heterocyclic systems and are also interesting as building blocks for many biologically active substances [5-9,11,23-33].

Results and Discussion

For the purposes of this study we used two β-enamino amides 1 (R1 = H, Ph), that are easily prepared in quantitative yields by condensation of Boc-monoprotected ethylenediamine with commercially available acetoacetamides. As a first step we acylated the starting compounds 1 with mixed carbonic anhydrides of N-protected amino acids, applying a procedure previously developed by us for closely related analogues [34] (Scheme 1). Thus, the α-C-acylated intermediates 3a–j (Table 1) and 4 (Table 2) were obtained in good yields and excellent chiral integrity (er 3c–f ≥ 99:1). The phthaloyl-protected compounds 3k and 3l were obtained in low yields by the mixed carbonic anhydride method and after screening various alternative coupling reagents (mixed pivalic anhydrides, T3P, DCC, DIC, CDI) we were able to improve the yields of 3k,l to 77% and 60%, respectively, only by using the corresponding N-phthaloyl amino acid chlorides [35,36] as acylating reagents. The increased yield however came at the expense of chiral integrity, with nearly full racemisation.

Scheme 1: Preparation of α-C-acylated β-enamino amides 3 and 4. Reagents and conditions: 2, NMM, EtOCOCl, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 5 min; then 1 and DMAP (0.2 equiv) in CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt, 1 h.

Scheme 1: Preparation of α-C-acylated β-enamino amides 3 and 4. Reagents and conditions: 2, NMM, EtOCOCl, CH2...

Table 1: Yields of compounds 3 and 5 (R1 = Ph, n = 0), obtained according to Scheme 1 and Scheme 2.

| Compound 3/5 | R2 | R3 | PG | Yield 3 (%) | Yield 5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | H | H | COOEt | 88 | 57 |

| b | H | H | Troc | 75 | 52 |

| c | CH3 | H | COOEt | 86 | 45 |

| d | CH3 | H | Troc | 65 | 62 |

| e | CH2Ph | H | COOEt | 85 | 70 |

| f | CH2Ph | H | Troc | 60 | 54 |

| g | H | CH3 | COOEt | 80 | 95 |

| h | H | CH3 | Troc | 80 | 90 |

| i | H | Ph | COOEt | 70 | 85 |

| j | H | COC6H4CO | 94 | 90 | |

| k | CH3 | COC6H4CO | 45 (77)a | 87 | |

| l | CH2Ph | COC6H4CO | 18 (60)a | 85 | |

aYields from acylation reaction with the corresponding acid chlorides.

Table 2: Yields of compounds 4 and 11 (R2 = R3 = H), obtained according to Scheme 1 and Scheme 6.

| compound 4/11 | R1 | n | PG | Yield 4 (%) | Yield 11 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Ph | 1 | COOEt | 90 | 95 |

| b | Ph | 2 | COOEt | 75 | 93 |

| c | Ph | 2 | Cbz | 88 | 74 |

| d | Ph | 3 | Cbz | 85 | 71 |

| e | Ph | 4 | Cbz | 75 | 68 |

| f | Ph | 2 | Troc | 57 | 90 |

| g | Ph | 3 | Troc | 77 | 60 |

| h | Ph | 4 | Troc | 65 | 73 |

| i | H | 1 | Cbz | 95 | 60 |

| j | H | 2 | Cbz | 82 | 58 |

| k | H | 3 | Cbz | 70 | 60 |

| l | H | 4 | Cbz | 73 | 55 |

After the series of α-aminoacyl (3) and ω-aminoacyl (4) intermediates were successfully prepared, we proceeded with the removal of the Boc protection group from the ethylenediamine moiety in order to trigger the domino fragmentation to the targeted β-keto amides. In the course of these experiments the two series of compounds showed markedly different behaviour.

Domino fragmentation of α-aminoacyl intermediates 3 to N-protected γ-amino-β-ketoamides 5

Initially we tried a procedure developed earlier by us for simpler β-keto amides (30 min in neat TFA, then aqueous NaOAc) [22]. In contrast to the preparation of non-functionalised β-keto amides, here these conditions led to satisfactory yields of keto amides 5 only for substrates 3 with R3 ≠ H (3g–l), while in all other cases (3a–f, R3 = H) gave significant amounts of pyrrolin-4-ones 6 as competing side products (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Domino fragmentation of 3 to β-keto amides 5 with competing cyclisation to pyrrolin-4-ones 6. Reagents and conditions: TFA (neat, 5 min, rt), then 3 M aqueous NaOAc.

Scheme 2: Domino fragmentation of 3 to β-keto amides 5 with competing cyclisation to pyrrolin-4-ones 6. Reage...

The relative amount of the side products 6 depended on the deprotection conditions and mainly on the duration of the exposure of 3 to acid. Given enough time, the treatment in neat or diluted TFA led to a complete transformation of 3a–f into 6 without formation of the desired β-keto amides 5a–f at all. On the contrary – when the deprotection was carried out for 5 min in neat TFA, the pyrrolinones 6 were the minor product and the β-keto amides 5a–f were obtained in higher, although still moderate, yields (Table 1). These results indicated that the acidic conditions required for the Boc deprotection favoured the unwanted side process (Scheme 3) and the aza-Michael/retro-Mannich sequence only takes place after the addition of NaOAc (Scheme 4).

Scheme 3: Proposed mechanism for the formation of side products 6.

Scheme 3: Proposed mechanism for the formation of side products 6.

Scheme 4: Proposed mechanism for the formation of the target β-keto amides 5.

Scheme 4: Proposed mechanism for the formation of the target β-keto amides 5.

It can be hypothesized that in acidic media the ammonium species 7, resulting from the deprotection of 3 followed by protonation, exists predominantly as an imino tautomer, stabilised by intramolecular H-bonding. Such a tautomer would be susceptible to favourable 5-exo-trig process, leading eventually to the pyrrolin-4-ones 6. This hypothesis is strongly supported by the behaviour of analogues 9 in which the auxiliary amino group is absent (Scheme 5). Under identical conditions (neat TFA, rt) compounds 9 do not react even after 12 hours. A reaction occurs only upon heating in TFA solution, but then the cyclisation mode is completely different and leads to enaminotetramic derivatives 10 instead of pyrrolin-4-ones 6 [34]. Another drawback caused by the acidic deprotection conditions was the loss of chiral integrity. When the deprotection of 3 was performed in neat TFA for 5 min, the keto amides 5c–f were obtained in poor enantiomeric excess and the concomitantly formed pyrrolinones 6c–f were fully racemic. This again is in sharp contrast to analogues 9, which cyclise to 10 with excellent retention of configuration [34].

Scheme 5: Reactivity of analogues 9, lacking the auxiliary amino group [34].

Scheme 5: Reactivity of analogues 9, lacking the auxiliary amino group [34].

Higher enantiomeric ratios for compounds 5 (87:13–80:20) were obtained with TFA/CH2Cl2 (1:4) and 15 min deprotection time, without any change in the yields indicated in Table 1. Experiments with more dilute TFA required longer deprotection time, which in turn gave advantage to the unwanted cyclisation to pyrrolinones 6 and lowered the yields of compounds 5. Only the phthaloyl-protected derivative 3k gave the corresponding keto amide 5k in both, high yield and good er (95:5) when the Boc-deprotection was performed in 1:9 TFA/CH2Cl2 for 30 min.

Domino fragmentation of ω-aminoacyl intermediates 4 to N-protected ω-amino-β-ketoamides 11

The longer chain in compounds 4 precludes the favourable 5-exo-trig process discussed earlier (Scheme 3) and accordingly there was no competing formation of cyclic side products. A different type of unwanted cyclisation occurred with the GABA derivatives 4b,c,f,j (n = 2) but here the competing process was slower and could be effectively avoided by limiting the deprotection time to 5 min in neat TFA. In this way a series of ω-amino-β-keto amides 11 with variable chain lengths and N-protection groups was successfully obtained (Scheme 6, Table 2).

Scheme 6: Domino fragmentation of compounds 4 (R2 = R3 = H) to N-protected ω-amino-β-keto amides 11.

Scheme 6: Domino fragmentation of compounds 4 (R2 = R3 = H) to N-protected ω-amino-β-keto amides 11.

Minor amounts of the enol tautomer (1–10%) were present in the CDCl3 solutions of all β-keto amides 5 and 11. Along with that, the 1H NMR spectra of the GABA-derivatives 11b,c,f,j (n = 2) in CDCl3 indicated a ring–chain tautomeric equilibrium with 55–75% share of the open chain form. Although an estimation of the tautomeric ratio was possible through a comparison of selected peak areas, the partial overlap and broadening of other signals prevented a full and unequivocal assignment. To circumvent this issue, we chose to lock the chain form by reducing the keto group in 11 with NaBH4 (Scheme 7). The alcohols 12 obtained in this way gave clean and well resolved NMR spectra. Similar tautomerism was observed in 11d,b,g,k (n = 3), but with negligible proportion of the ring tautomer.

Scheme 7: Ring–chain tautomerism in compounds 11b,c,f,j (n = 2) and reduction to the corresponding β-hydroxy amides 12.

Scheme 7: Ring–chain tautomerism in compounds 11b,c,f,j (n = 2) and reduction to the corresponding β-hydroxy ...

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that N-protected γ-amino-β-keto amides and ω-amino-β-keto amides can be obtained from amino acids and β-enamino amides through the aza-Michael/retro-Mannich domino approach. A competing cyclisation to pyrrolin-4-ones limits the range of accessible γ-amino-derivatives and imposes the requirement for tertiary-substituted nitrogen in the aminoacyl moiety. There is no such limitation for the ω-amino derivatives.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Bulgarian National Science Fund (Grant DN09/15-2016) and the Royal Society of Chemistry, UK (Grant RF17-6592). The authors are grateful to the Faculty of Biology, Department of Plant Physiology and Molecular Biology and Dr Mladen Naydenov for carrying out high resolution mass spectral measurements on equipment provided under the EC FP7/REGPOT-2009-1/BioSupport project.

References

-

Bao, D.-H.; Gu, X.-S.; Xie, J.-H.; Zhou, Q.-L. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 118–121. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03397

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Agejas, J.; Ortega, L. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 6509–6514. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b00796

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McDonald, S. L.; Wang, Q. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 2535–2538. doi:10.1039/c3cc49296f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yip, K.-T.; Li, J.-H.; Lee, O.-Y.; Yang, D. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5717–5719. doi:10.1021/ol052529c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vaske, Y. S. M.; Mahoney, M. E.; Konopelski, J. P.; Rogow, D. L.; McDonald, W. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11379–11385. doi:10.1021/ja1050023

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gerstenberger, B. S.; Lin, J.; Mimieux, Y. S.; Brown, L. E.; Oliver, A. G.; Konopelski, J. P. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 369–372. doi:10.1021/ol7025922

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Jacobine, A. M.; Lin, W.; Walls, B.; Zercher, C. K. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7409–7412. doi:10.1021/jo801258h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

DiPardo, R. M.; Bock, M. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 4805–4808. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)94012-7

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kulesza, A.; Ebetino, F. H.; Mazur, A. W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 5511–5514. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(03)01226-7

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gay, R. L.; Hauser, C. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 1647–1651. doi:10.1021/ja00983a021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McWhorter, W.; Fredenhagen, A.; Nakanishi, K.; Komura, H. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989, 299–301. doi:10.1039/c39890000299

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Morwick, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 3227–3230. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78652-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Herschhorn, A.; Lerman, L.; Weitman, M.; Gleenberg, I. O.; Nudelman, A.; Hizi, A. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 2370–2384. doi:10.1021/jm0613121

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chen, Y.; Sieburth, S. M. Synthesis 2002, 2191–2194. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34845

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eby, C. J.; Hauser, C. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 723–725. doi:10.1021/ja01560a060

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, C.; Xu, J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 6375–6383. doi:10.1039/c7ob01356f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

González-Fernández, R.; Crochet, P.; Cadierno, V. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 6164–6167. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03172

Return to citation in text: [1] -

González-Fernández, R.; González-Liste, P. J.; Borge, J.; Crochet, P.; Cadierno, V. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 4398–4409. doi:10.1039/c5cy02142a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gotor, V.; Liz, R.; Testera, A. M. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 607–618. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2003.10.096

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hauser, C. R.; Eby, C. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 725–727. doi:10.1021/ja01560a061

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuzma, P. C.; Brown, L. E.; Harris, T. M. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 2015–2018. doi:10.1021/jo00185a038

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Angelov, P. Synlett 2010, 1273–1275. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1219836

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Dockerty, P.; Edens, J. G.; Tol, M. B.; Morales Angeles, D.; Domenech, A.; Liu, Y.; Hirsch, A. K. H.; Veening, J.-W.; Scheffers, D.-J.; Witte, M. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 894–910. doi:10.1039/c6ob01664b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, C.; Li, X.; liang, X.; Jin, K.; Cao, J.; Xu, W. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 4948–4952. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.058

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bai, R.; Bates, R. B.; Hamel, E.; Moore, R. E.; Nakkiew, P.; Pettit, G. R.; Sufi, B. A. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1824–1829. doi:10.1021/np020117w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bates, R. B.; Brusoe, K. G.; Burns, J. J.; Caldera, S.; Cui, W.; Gangwar, S.; Gramme, M. R.; McClure, K. J.; Rouen, G. P.; Schadow, H.; Stessman, C. C.; Taylor, S. R.; Vu, V. H.; Yarick, G. V.; Zhang, J.; Pettit, G. R.; Bontems, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2111–2113. doi:10.1021/ja963857y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohtake, N.; Jona, H.; Okada, S.; Okamoto, O.; Imai, Y.; Ushijima, R.; Nakagawa, S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 2939–2947. doi:10.1016/s0957-4166(97)00315-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

DiMaio, J.; Gibbs, B.; Lefebvre, J.; Konishi, Y.; Munn, D.; Yue, S. Y.; Hornberger, W. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35, 3331–3341. doi:10.1021/jm00096a004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rich, D. H.; Bernatowicz, M. S. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 1999–2001. doi:10.1021/jo00160a011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Haviv, F.; Henkin, J.; Bradley, M. F.; Kalvin, D. M.; Schneider, A. J. Peptides having antiangiogenic activity. U.S. Patent US6753408B1, Nov 22, 1999.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marzilli, L. G.; Lipowska, M.; Hansen, L.; Taylor, A. Metal chelates as pharmaceutical imaging agents, processes of making such and uses thereof. U.S. Patent US5986074A, May 6, 1996.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Doherty, A. M.; Kaltenbronn, J. S.; Leonard, D. M.; McNamara, D. J. Cycloalkyl inhibitors of protein farnesyltransferase. U.S. Patent US6281194B1, Dec 17, 1996.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nestor, J. J.; Jones, G. H.; Vickery, B. H. Nonapeptide and decapeptide agonists of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone containing heterocyclic amino acid residues. U.S. Patent US4318905A, June 23, 1980.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Angelov, P.; Ivanova, S.; Yanev, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4776–4778. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.11.023

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Gruzdev, D. A.; Levit, G. L.; Krasnov, V. P.; Chulakov, E. N.; Sadretdinova, L. S.; Grishakov, A. N.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Charushin, V. N. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 936–942. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.05.013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prabhu, G.; Basavaprabhu; Narendra, N.; Vishwanatha, T. M.; Sureshbabu, V. V. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 2785–2832. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2015.03.026

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Bao, D.-H.; Gu, X.-S.; Xie, J.-H.; Zhou, Q.-L. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 118–121. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03397 |

| 2. | Agejas, J.; Ortega, L. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 6509–6514. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b00796 |

| 3. | McDonald, S. L.; Wang, Q. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 2535–2538. doi:10.1039/c3cc49296f |

| 4. | Yip, K.-T.; Li, J.-H.; Lee, O.-Y.; Yang, D. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5717–5719. doi:10.1021/ol052529c |

| 5. | Vaske, Y. S. M.; Mahoney, M. E.; Konopelski, J. P.; Rogow, D. L.; McDonald, W. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11379–11385. doi:10.1021/ja1050023 |

| 6. | Gerstenberger, B. S.; Lin, J.; Mimieux, Y. S.; Brown, L. E.; Oliver, A. G.; Konopelski, J. P. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 369–372. doi:10.1021/ol7025922 |

| 7. | Jacobine, A. M.; Lin, W.; Walls, B.; Zercher, C. K. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7409–7412. doi:10.1021/jo801258h |

| 8. | DiPardo, R. M.; Bock, M. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 4805–4808. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)94012-7 |

| 9. | Kulesza, A.; Ebetino, F. H.; Mazur, A. W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 5511–5514. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(03)01226-7 |

| 13. | Herschhorn, A.; Lerman, L.; Weitman, M.; Gleenberg, I. O.; Nudelman, A.; Hizi, A. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 2370–2384. doi:10.1021/jm0613121 |

| 16. | Xu, C.; Xu, J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 6375–6383. doi:10.1039/c7ob01356f |

| 17. | González-Fernández, R.; Crochet, P.; Cadierno, V. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 6164–6167. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03172 |

| 18. | González-Fernández, R.; González-Liste, P. J.; Borge, J.; Crochet, P.; Cadierno, V. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 4398–4409. doi:10.1039/c5cy02142a |

| 19. | Gotor, V.; Liz, R.; Testera, A. M. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 607–618. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2003.10.096 |

| 20. | Hauser, C. R.; Eby, C. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 725–727. doi:10.1021/ja01560a061 |

| 13. | Herschhorn, A.; Lerman, L.; Weitman, M.; Gleenberg, I. O.; Nudelman, A.; Hizi, A. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 2370–2384. doi:10.1021/jm0613121 |

| 14. | Chen, Y.; Sieburth, S. M. Synthesis 2002, 2191–2194. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34845 |

| 15. | Eby, C. J.; Hauser, C. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 723–725. doi:10.1021/ja01560a060 |

| 11. | McWhorter, W.; Fredenhagen, A.; Nakanishi, K.; Komura, H. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989, 299–301. doi:10.1039/c39890000299 |

| 12. | Morwick, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 3227–3230. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)78652-7 |

| 34. | Angelov, P.; Ivanova, S.; Yanev, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4776–4778. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.11.023 |

| 10. | Gay, R. L.; Hauser, C. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 1647–1651. doi:10.1021/ja00983a021 |

| 34. | Angelov, P.; Ivanova, S.; Yanev, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4776–4778. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.11.023 |

| 34. | Angelov, P.; Ivanova, S.; Yanev, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4776–4778. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.11.023 |

| 5. | Vaske, Y. S. M.; Mahoney, M. E.; Konopelski, J. P.; Rogow, D. L.; McDonald, W. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11379–11385. doi:10.1021/ja1050023 |

| 6. | Gerstenberger, B. S.; Lin, J.; Mimieux, Y. S.; Brown, L. E.; Oliver, A. G.; Konopelski, J. P. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 369–372. doi:10.1021/ol7025922 |

| 7. | Jacobine, A. M.; Lin, W.; Walls, B.; Zercher, C. K. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7409–7412. doi:10.1021/jo801258h |

| 8. | DiPardo, R. M.; Bock, M. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 4805–4808. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)94012-7 |

| 9. | Kulesza, A.; Ebetino, F. H.; Mazur, A. W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 5511–5514. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(03)01226-7 |

| 11. | McWhorter, W.; Fredenhagen, A.; Nakanishi, K.; Komura, H. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989, 299–301. doi:10.1039/c39890000299 |

| 23. | Dockerty, P.; Edens, J. G.; Tol, M. B.; Morales Angeles, D.; Domenech, A.; Liu, Y.; Hirsch, A. K. H.; Veening, J.-W.; Scheffers, D.-J.; Witte, M. D. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 894–910. doi:10.1039/c6ob01664b |

| 24. | Ma, C.; Li, X.; liang, X.; Jin, K.; Cao, J.; Xu, W. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 4948–4952. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.058 |

| 25. | Bai, R.; Bates, R. B.; Hamel, E.; Moore, R. E.; Nakkiew, P.; Pettit, G. R.; Sufi, B. A. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1824–1829. doi:10.1021/np020117w |

| 26. | Bates, R. B.; Brusoe, K. G.; Burns, J. J.; Caldera, S.; Cui, W.; Gangwar, S.; Gramme, M. R.; McClure, K. J.; Rouen, G. P.; Schadow, H.; Stessman, C. C.; Taylor, S. R.; Vu, V. H.; Yarick, G. V.; Zhang, J.; Pettit, G. R.; Bontems, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2111–2113. doi:10.1021/ja963857y |

| 27. | Ohtake, N.; Jona, H.; Okada, S.; Okamoto, O.; Imai, Y.; Ushijima, R.; Nakagawa, S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 2939–2947. doi:10.1016/s0957-4166(97)00315-7 |

| 28. | DiMaio, J.; Gibbs, B.; Lefebvre, J.; Konishi, Y.; Munn, D.; Yue, S. Y.; Hornberger, W. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35, 3331–3341. doi:10.1021/jm00096a004 |

| 29. | Rich, D. H.; Bernatowicz, M. S. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 1999–2001. doi:10.1021/jo00160a011 |

| 30. | Haviv, F.; Henkin, J.; Bradley, M. F.; Kalvin, D. M.; Schneider, A. J. Peptides having antiangiogenic activity. U.S. Patent US6753408B1, Nov 22, 1999. |

| 31. | Marzilli, L. G.; Lipowska, M.; Hansen, L.; Taylor, A. Metal chelates as pharmaceutical imaging agents, processes of making such and uses thereof. U.S. Patent US5986074A, May 6, 1996. |

| 32. | Doherty, A. M.; Kaltenbronn, J. S.; Leonard, D. M.; McNamara, D. J. Cycloalkyl inhibitors of protein farnesyltransferase. U.S. Patent US6281194B1, Dec 17, 1996. |

| 33. | Nestor, J. J.; Jones, G. H.; Vickery, B. H. Nonapeptide and decapeptide agonists of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone containing heterocyclic amino acid residues. U.S. Patent US4318905A, June 23, 1980. |

| 34. | Angelov, P.; Ivanova, S.; Yanev, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 4776–4778. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.11.023 |

| 21. | Kuzma, P. C.; Brown, L. E.; Harris, T. M. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 2015–2018. doi:10.1021/jo00185a038 |

| 35. | Gruzdev, D. A.; Levit, G. L.; Krasnov, V. P.; Chulakov, E. N.; Sadretdinova, L. S.; Grishakov, A. N.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Charushin, V. N. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 936–942. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.05.013 |

| 36. | Prabhu, G.; Basavaprabhu; Narendra, N.; Vishwanatha, T. M.; Sureshbabu, V. V. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 2785–2832. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2015.03.026 |

© 2018 Yanev and Angelov; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)