Abstract

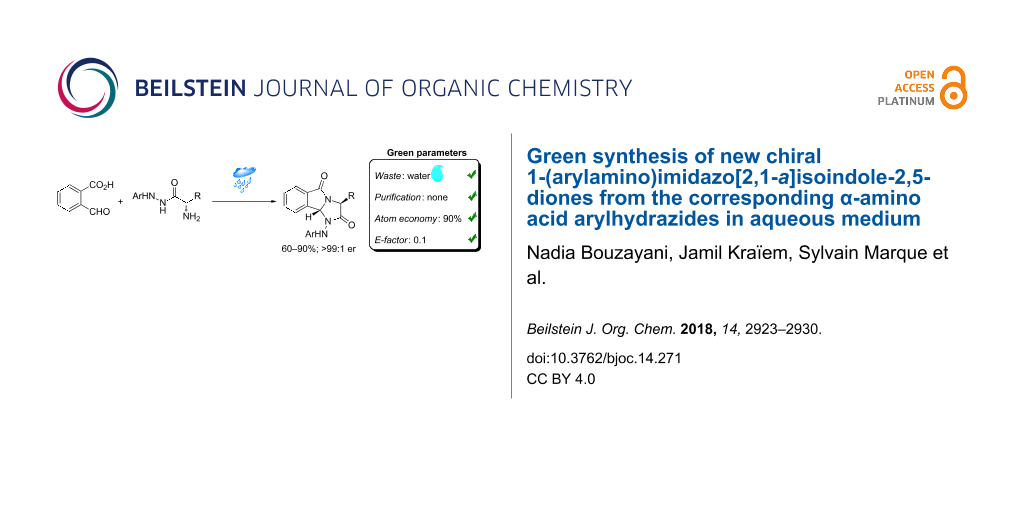

New chiral 1-(arylamino)imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5-dione derivatives were obtained in good to excellent yields via the cyclocondensation of 2-formylbenzoic acid and various α-amino acid arylhydrazides using water as the solvent in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate as the surfactant and under simple and minimum manipulation, without purification. The reaction is totally diastereoselective and gives access to the nitrogenated tricyclic core with a relative trans stereochemistry.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Tricyclic compounds, such as imidazo[2,1-a]isoindol-5-ones, are widely distributed in nature and possess several biological activities. In 1967, Geigy described the preparation of 1,2,3,9b-tetrahydro-5H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindol-5-ones I which are recognized as anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents [1]. Other compounds, such as 1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5-diones II have been known as an important herbicides for bud growth inhibition [2-6] and plant growth regulation [7-11]. Several research groups have turned to the synthesis of these structural analogues (Figure 1) [12]. For example, the stereoselective synthesis of chiral 1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5(3H,9bH)-diones [6] and 1,2,3,9b-tetrahydro-5H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindol-5-ones [13] has been described by Katritzky et al. using α-aminoamides and diamines, respectively.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of analogues.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of analogues.

Also, the imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5-dione derivatives of primaquin have been synthesized from α-amino acids [14]. Focusing on the 1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindolone skeleton, Hosseini-Zare et al. reported the synthesis of new 2,3-diaryl-5H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindol-5-ones via the one pot reaction of 1,2-diketones, 2-formylbenzoic acid and ammonium acetate [15]. These methodologies usually use toxic solvents such as benzene [16], dichloromethane and some catalyst such as para-toluenesulfonic acid [17]. Furthermore, most of them induce to manage undesirable waste produced in stoichiometric amounts. Recently, such synthetic methods utilizing hazardous solvents and reagents and generating toxic waste have become discouraged and there have been many efforts to develop safer and environmentally benign alternatives. The green chemistry concept emerged in 1990 [18] with the aim at developing cleaner approaches through the simplification of chemical processing along with the decreases of waste and cost. As a part of our ongoing efforts directed toward the development of environmentally safe conditions for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds starting from natural (L)-α-amino acids [19-23] and the reactivity of α-amino acid phenylhydrazides [24,25], we now report a green and eco-friendly procedure for the synthesis of new chiral 1-(arylamino)-1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5(3H,9bH)-diones (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Strategy for the formation of 1-(arylamino)-1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5(3H,9bH)-diones.

Scheme 1: Strategy for the formation of 1-(arylamino)-1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5(3H,9bH)-diones.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

The starting (L)-α-amino acid arylhydrazides 3 were prepared in a manner similar to the well-known procedures [26-28], improving the amount of the added arylhydrazine 2 down to 2.5 equiv (Scheme 2, Table 1) in a sealed tube in the presence of Et3N and under solvent-free conditions. From green chemistry point of view, this enhanced procedure appears to be a good alternative of the precedents for the synthesis of hydrazides 3a–m [26-29]. Moreover, the phenylglycine phenylhydrazide (3d), (L)-cysteine phenylhydrazide (3g), (L)-tyrosine phenylhydrazide (3j), (L)-alanine 4-chlorophenylhydrazide (3k), (L)-phenylglycine 4-chlorophenylhydrazide (3l) and (L)-phenylalanine 4-chlorophenylhydrazide (3m) were synthesized for the first time in this work.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of the starting (L)-α-amino acid phenylhydrazides and 4-chlorophenylhydrazides 3a–m under solvent-free conditions.

Scheme 2: Synthesis of the starting (L)-α-amino acid phenylhydrazides and 4-chlorophenylhydrazides 3a–m under...

Table 1: Synthesis of the α-amino acid arylhydrazides 3a–m.

| entry | product (mol %) | R | R’ | yielda [%] | mp [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3a | Me | H | 87 | 122–124 |

| 2 | 3b | iPr | H | 80 | 138–140 |

| 3 | 3c | iBu | H | 70 | 152–154 |

| 4 | 3db | Ph | H | 83 | 138–140 |

| 5 | 3e | Bn | H | 93 | 142–144 |

| 6 | 3f | (CH2)2SMe | H | 81 | 128–130 |

| 7 | 3g | CH2SH | H | 71 | 98–100 |

| 8 | 3h | CH2OH | H | 71 | 163–165 |

| 9 | 3i | 3-CH2-1H-indole | H | 80 | 168–170 |

| 10 | 3j | CH2C6H4OH | H | 77 | 134–136 |

| 11 | 3k | Me | Cl | 69 | 128–130 |

| 12 | 3l | Ph | Cl | 70 | 135–137 |

| 13 | 3m | Bn | Cl | 74 | 140–142 |

aYield of the isolated product. bThe compound 3d was obtained as a racemic mixture.

Verardo et al. [29] have shown that refluxing α-amino acid phenylhydrazides with levulinic acid in toluene led to the corresponding dihydro-1H-pyrrolo[1,2-a]imidazole-2,5-diones. These authors explained clearly the behavior of the solvent and its influence in the reaction. In addition, substituted 1-hydroxy-1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5(3H,9bH)-diones have been synthesized by the condensation of (L)-α-aminohydroxamic acids and 2-formylbenzoic acid under the same conditions [30]. Thus, they choose toluene as the best solvent for this reaction. To prepare the new chiral 1-(arylamino)imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5-diones 5a–m under greener conditions, we investigated the reaction in nontoxic solvents such as water and dimethyl carbonate (DMC). Indeed, DMC is well-known as safe reagent and solvent that has been used for many green applications [31-33]. On the other hand, water is a simply and environmentally benign solvent and interest has increasingly turned to it as the greenest solvent of chemical reactions [34]. In order to find the best reaction conditions, a model reaction was chosen using (L)-alanine phenylhydrazide (3a, Scheme 3), and the results of these optimized studies were summarized in Table 2.

Scheme 3: Cyclocondensation of 2-formylbenzoic acid (4) with (L)-alanine phenylhydrazide (3a).

Scheme 3: Cyclocondensation of 2-formylbenzoic acid (4) with (L)-alanine phenylhydrazide (3a).

Table 2: Optimization of the reaction conditions for the cyclocondensation of 2-formylbenzoic acid (4) with (L)-alanine phenylhydrazide (3a).a

aGeneral conditions for all the six entries: (L)-alanine phenylhydrazide (0.66 mmol), 2-formylbenzoic acid (0.66 mmol), 120 °C. bConditions: DMC (1.5 mL) in sealed tube. cConditions: water (1.5 mL) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in sealed tube. dConditions: in sealed tube. eConditions: toluene (3 mL), under argon.

The best result was obtained when a mixture of hydrazide 3a and formylbenzoic acid 4 was heated at 120 °C (oil bath) using water as the solvent in the presence of SDS (10%) as the surfactant for 10 h leading to a 90% yield in 5a. To demonstrate the generality of this method, we next investigated the scope of this reaction under the optimized conditions. A variety of the 1-(arylamino)imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5-diones 5b–m were prepared and the obtained results are summarized in Scheme 4. The mild conditions of the reaction gave access to the tricyclic compounds 5a–m providing similar yields, regardless the amino acid residue is. A weak acidic function was well-tolerated yielding 5j with 66%. Bulky groups did not roughly affect the efficiency of the reactivity (5b, 5c).

Scheme 4: Synthesis of the nitrogenated tricyclic compounds 5a–m. Diastereoisomeric (dr) and enantiomeric (er) ratio were determined by chiral HPLC (see Supporting Information File 3).

Scheme 4: Synthesis of the nitrogenated tricyclic compounds 5a–m. Diastereoisomeric (dr) and enantiomeric (er...

The new approach described in this work for the preparation of compounds 5a–m has the following advantages: (i) notably, under the reaction conditions described above, we have never observed the formation of degradation products. (ii) The reaction was performed in water, in the presence of SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate) as the surfactant. Based on previous studies [35], the most effective method for ensuring the solubility of reactants in water is the use of surfactants that can form micelles with a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic corona. (iii) This clean method afforded compounds 5a–m without the need of additional purification such as column chromatography or recrystallization. (iv) The use of a sealed tube [36-43] obeys to four out of the twelve green chemistry principles: a cleaner and eco-friendly reaction profile with minimum of waste, solvent without negative environmental impact, shorter reaction time and safely work with a pressure tube canning prevent fires and emissions of hazardous compounds and toxic gas. (v) The reaction described in this work occurred with high atom efficiency (atom economy of 90%) and produced only stoichiometric H2O as waste (E-factor of 0.1).

Stereochemistry and mechanism

The stereochemistries of 5a–m were ascribed by NOE NMR experiments. By example using 5a depicted in Figure 2, the 1H NMR spectrum showed that H(1) appears at 5.95 ppm as a singlet and H(4) at 4.72 ppm as a quadruplet. No distinct NOE effect was observed between H(1) and H(4), when either H(1) or H(4) was irradiated. A significant positive NOE effect was observed between H(1) and H(20). Thus, NOE analysis assumed that H(1) is in a trans-orientation with H(4).

Figure 2: NOEs correlation showing the stereochemistry of the compound 5a.

Figure 2: NOEs correlation showing the stereochemistry of the compound 5a.

In addition, various crystallization tests were carried out in order to confirm the absolute stereochemistry by X-ray diffraction. The chiral 3-(2-(methylthio)ethyl)-1-(phenylamino)-1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5(3H,9bH)dione (5f) crystallized [44-49] using a mixture of CH2Cl2/diethyl ether (3:1) as a single diastereoisomer with the (3S,9R) configuration (Figure 3) showing clearly the trans relative stereochemistry.

![[1860-5397-14-271-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-14-271-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: X-ray crystal structure of 5f shown at the 30% probability level.

Figure 3: X-ray crystal structure of 5f shown at the 30% probability level.

The dihedral angle value of −163.1° for H(1)–C(1)–C(4)–H(4) close to the anti-planarity corroborates the expected non correlation between H(1) and H(4) in the NOE experiment. The structure contains two carbonyl moieties C(6)–O(2) and C(3)–O(1) with similar distances of 1.222 and 1.218 Å, respectively. The intramolecular hydrogen bond O(1)–H(13) remains strong in the nitrogenated tricycle (2.579 Å) vis-à-vis of the starting hydrazide.

Analyzing the mechanism of the reaction between the 2-formylbenzoic acid 4 and α-amino acid arylhydrazides 3, we assumed that the first steps lead to the formation of the imine intermediate A, which is the result of the nucleophile addition of the α-amino group on the most electrophilic center in 4. This imino-carboxylic acid form likely evolves to its iminium-carboxylate form B [50]. This last intermediate involves the existence of two possible transition states for the cyclization of the imidazolidinone core of which one of them is favored by an intramolecular hydrogen bond (Scheme 5). This control is the main difference with the known reaction [51] between the hydrazides 3 and the phthalaldehydes in which two diasteroisomers have been observed. If the amino acid residue (R on the Scheme 5) enough implicates steric hindrance with the carboxyaromatic part of B, the pathway with disfavored transition state becomes unlikely and then the selectivity is important. Our model is in agreement with the diasteroisomeric ratio results. In fact, a total diastereoselectivity was observed, including 5d (R = Ph) since an epimerization of the initial asymmetric center was observed, therefore racemic trans-isomers were obtained in this case. Interestingly, acidic (phenolic 5j) and basic moieties (as indolyl 5i) on the amino acid residue did not affect the selectivity.

Scheme 5: Proposed partial mechanism with a selectivity model.

Scheme 5: Proposed partial mechanism with a selectivity model.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed environmentally safe conditions for the synthesis of new chiral 1-(arylamino)-1H-imidazo[2,1-a]isoindole-2,5(3H,9bH)-diones in good yields using water as the solvent in sealed tube. The aspects of greenness and good results make this methodology a practical and atom economical alternative in the whole of the processing since the syntheses of the α-amino acid arylhydrazide precursors behave this greener aspect. Once more, the processing includes this eco-friendly way up to have the compounds in hand since simple precipitation allows to isolate the nitrogenated tricyclic compounds; no purification is needed. The model for the key step of the cyclization clearly explains the stereochemistries, which are observed with a total trans-diastereoselectivity controlled by intramolecular hydrogen bonds.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, spectroscopic and analytical data and copies of spectra of the products. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.6 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: Crystallographic information for compound 5f. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 134.1 KB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 3: HPLC analysis of the products. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 345.1 KB | Download |

References

-

Geigy, J. R. Neth. Appl. 6,613,264, 1967.

Chem. Abstr. 1967, 67, 82204q.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Graf, W. Swiss Patent 481,123, 1969.

Chem. Abstr. 1970, 72, 100709t.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Los, M. U.S. Patent USP 4,041,045, 1977.

Chem. Abstr. 1977, 87, 168034j.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ashkar, S. A. U.S. Patent USP 4,090,860, 1978.

Chem. Abstr. 1978, 89, 192503y.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ashkar, S. A. U.S. Patent USP 4,067,718, 1978.

Chem. Abstr. 1978, 88, 165485s.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ashkar, S. A. U.S. Patent USP 4,093,441, 1978.

Chem. Abstr. 1979, 90, 49647p.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Katritzky, A. R.; Mehta, S.; He, H.-Y.; Cui, X. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4364–4369. doi:10.1021/jo000219w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Polniaszek, R. P.; Belmont, S. E. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4868–4874. doi:10.1021/jo00016a013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meyers, A. I.; Seefeld, M. A.; Lefker, B. A.; Blake, J. F.; Williard, P. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 7429–7438. doi:10.1021/ja980614s

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burgess, L. E.; Meyers, A. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 9858–9859. doi:10.1021/ja00026a026

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Burgess, L. E.; Meyers, A. I. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 1656–1662. doi:10.1021/jo00032a012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Katritzky, A. R.; Xu, Y.-J.; He, H.-Y.; Steel, P. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 1767–1770. doi:10.1039/b104060j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Katritzky, A. R.; He, H.-Y.; Verma, A. K. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2002, 13, 933–938. doi:10.1016/s0957-4166(02)00220-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gomes, P.; Araújo, J. M.; Rodrigues, M.; Vale, N.; Azevedo, Z.; Iley, J.; Chambel, P.; Morais, J.; Moreira, R. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 5551–5562. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.04.077

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hosseini-Zare, M. S.; Mahdavi, M.; Saeedi, M.; Asadi, M.; Javanshir, S.; Shafiee, A.; Foroumadi, A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 3448–3451. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.04.088

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Katritzky, A. R.; He, H.-Y.; Jiang, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 2831–2833. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(02)00350-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ramirez, A. Agrees to Purchase Part of American Cyanamid, Wall Street Journal, June 1990, 14.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kacem, Y.; Kraiem, J.; Kerkeni, E.; Bouraoui, A.; Ben Hassine, B. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002, 16, 221–228. doi:10.1016/s0928-0987(02)00046-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aliyenne, A. O.; Khiari, J. E.; Kraïem, J.; Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 6405–6408. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.06.148

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aliyenne, A. O.; Kraïem, J.; Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 1473–1475. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.01.015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tka, N.; Kraïem, J.; Kacem, Y.; Hajri, A.; Ben Hassine, B. C. R. Chim. 2009, 12, 1066–1071. doi:10.1016/j.crci.2008.09.004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5608–5610. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.08.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 252–257. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2013.12.002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Heterocycles 2014, 89, 197–207. doi:10.3987/com-13-12878

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Milne, H. B.; Most, C. F. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 169–175. doi:10.1021/jo01265a032

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Verardo, G.; Toniutti, N.; Gorassini, A.; Giumanini, A. G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 2943–2948. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0690(199911)1999:11<2943::aid-ejoc2943>3.0.co;2-x

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Verardo, G.; Geatti, P.; Martinuzzi, P.; Merli, M.; Toniutti, N. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 3840–3849. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200300251

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Verardo, G.; Toniutti, N.; Giumanini, A. G. Can. J. Chem. 1998, 76, 1180–1187. doi:10.1139/v98-125

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Verardo, G.; Geatti, P.; Merli, M.; Castellarin, E. E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 2833–2839. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200400112

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hoshino, Y.; Oyaizu, M.; Koyanagi, Y.; Honda, K. Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 2484–2492. doi:10.1080/00397911.2012.717162

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tundo, P.; Selva, M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 706–716. doi:10.1021/ar010076f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rosamilia, A. E.; Aricò, F.; Tundo, P. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 1559–1562. doi:10.1021/jo701818d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kraïem, J.; Ghedira, D.; Ollevier, T. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4859–4864. doi:10.1039/c6gc01394e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kraïem, J.; Ollevier, T. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1263–1267. doi:10.1039/c6gc03589b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kobayashi, S.; Wakabayashi, T.; Nagayama, S.; Oyamada, H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 4559–4562. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(97)00854-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kobayashi, S.; Wakabayashi, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 5389–5392. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(98)01081-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manabe, K.; Kobayashi, S. Synlett 1999, 547–548. doi:10.1055/s-1999-2685

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Manabe, K.; Mori, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 11203–11208. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(99)00642-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kobayashi, S.; Mori, Y.; Nagayama, S.; Manabe, K. Green Chem. 1999, 1, 175–177. doi:10.1039/a904439f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kobayashi, S.; Manabe, K. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 209–217. doi:10.1021/ar000145a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Landelle, H.; Laduree, D.; Cugnon de Servicourt, M.; Robba, M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1989, 37, 2679–2682. doi:10.1248/cpb.37.2679

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suzuki, T.; Kubomura, K.; Takayama, H. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1997, 251–256. doi:10.1039/a604600b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bhakuni, B. S.; Yadav, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, S. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 827–836. doi:10.1039/c3nj01105d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

SADABS, program for scaling and correction of area detector data; Sheldrick, G. M.: University of Göttingen, Germany, 1997.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blessing, R. H. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1995, 51, 33–38. doi:10.1107/s0108767394005726

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1990, 46, 467–473. doi:10.1107/s0108767390000277

Return to citation in text: [1] -

SHELX-TL Software Package for the Crystal Structure Determination, 5.03; Sheldrick, G. M.: Siemens Analytical X-ray Instrument Division : Madison, WI USA, 1994.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif; C19H19N3O2S, Mw = 353.43, orthorhombic, space group P212121; dimensions: a = 6.3980(3) Å, b = 14.3384(6) Å, c = 19.2989(9) Å, V = 1770.42(14) Å3; Z = 4; Dx = 1.326 Mg m−3; µ = 0.200 mm−1; 33260 reflections measured at 250 K; independent reflections: 3136 [2939 Fo > 4σ(Fo)]; data were collected up to a 2Θmax value of 50.05° (99.7% coverage). Number of variables: 231; R1 = 0.0322, wR2 = 0.0807, S = 1.078; highest residual electron density 0.15 e.Å–3; CCDC = 1829108.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Macrae, C. F.; Bruno, I. J.; Chisholm, J. A.; Edgington, P. R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; van de Streek, J.; Wood, P. A. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. doi:10.1107/s0021889807067908

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bouzayani, N.; Marque, S.; Djelassi, B.; Kacem, Y.; Marrot, J.; Ben Hassine, B. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 6389–6398. doi:10.1039/c7nj04597b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bouzayani, N.; Talbi, W.; Marque, S.; Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. ARKIVOC 2018, No. iii, 229–239. doi:10.24820/ark.5550190.p010.297

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 26. | Verardo, G.; Toniutti, N.; Gorassini, A.; Giumanini, A. G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 2943–2948. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0690(199911)1999:11<2943::aid-ejoc2943>3.0.co;2-x |

| 27. | Verardo, G.; Geatti, P.; Martinuzzi, P.; Merli, M.; Toniutti, N. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 3840–3849. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200300251 |

| 28. | Verardo, G.; Toniutti, N.; Giumanini, A. G. Can. J. Chem. 1998, 76, 1180–1187. doi:10.1139/v98-125 |

| 29. | Verardo, G.; Geatti, P.; Merli, M.; Castellarin, E. E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 2833–2839. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200400112 |

| 12. | Katritzky, A. R.; Xu, Y.-J.; He, H.-Y.; Steel, P. J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 1767–1770. doi:10.1039/b104060j |

| 29. | Verardo, G.; Geatti, P.; Merli, M.; Castellarin, E. E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 2833–2839. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200400112 |

| 7. | Katritzky, A. R.; Mehta, S.; He, H.-Y.; Cui, X. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4364–4369. doi:10.1021/jo000219w |

| 8. | Polniaszek, R. P.; Belmont, S. E. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4868–4874. doi:10.1021/jo00016a013 |

| 9. | Meyers, A. I.; Seefeld, M. A.; Lefker, B. A.; Blake, J. F.; Williard, P. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 7429–7438. doi:10.1021/ja980614s |

| 10. | Burgess, L. E.; Meyers, A. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 9858–9859. doi:10.1021/ja00026a026 |

| 11. | Burgess, L. E.; Meyers, A. I. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 1656–1662. doi:10.1021/jo00032a012 |

| 24. | Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Heterocycles 2014, 89, 197–207. doi:10.3987/com-13-12878 |

| 25. | Milne, H. B.; Most, C. F. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 169–175. doi:10.1021/jo01265a032 |

| 2. |

Graf, W. Swiss Patent 481,123, 1969.

Chem. Abstr. 1970, 72, 100709t. |

| 3. |

Los, M. U.S. Patent USP 4,041,045, 1977.

Chem. Abstr. 1977, 87, 168034j. |

| 4. |

Ashkar, S. A. U.S. Patent USP 4,090,860, 1978.

Chem. Abstr. 1978, 89, 192503y. |

| 5. |

Ashkar, S. A. U.S. Patent USP 4,067,718, 1978.

Chem. Abstr. 1978, 88, 165485s. |

| 6. |

Ashkar, S. A. U.S. Patent USP 4,093,441, 1978.

Chem. Abstr. 1979, 90, 49647p. |

| 26. | Verardo, G.; Toniutti, N.; Gorassini, A.; Giumanini, A. G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 2943–2948. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0690(199911)1999:11<2943::aid-ejoc2943>3.0.co;2-x |

| 27. | Verardo, G.; Geatti, P.; Martinuzzi, P.; Merli, M.; Toniutti, N. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 3840–3849. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200300251 |

| 28. | Verardo, G.; Toniutti, N.; Giumanini, A. G. Can. J. Chem. 1998, 76, 1180–1187. doi:10.1139/v98-125 |

| 16. | Katritzky, A. R.; He, H.-Y.; Jiang, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 2831–2833. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(02)00350-7 |

| 18. | Kacem, Y.; Kraiem, J.; Kerkeni, E.; Bouraoui, A.; Ben Hassine, B. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002, 16, 221–228. doi:10.1016/s0928-0987(02)00046-5 |

| 15. | Hosseini-Zare, M. S.; Mahdavi, M.; Saeedi, M.; Asadi, M.; Javanshir, S.; Shafiee, A.; Foroumadi, A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 3448–3451. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.04.088 |

| 19. | Aliyenne, A. O.; Khiari, J. E.; Kraïem, J.; Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 6405–6408. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.06.148 |

| 20. | Aliyenne, A. O.; Kraïem, J.; Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 1473–1475. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.01.015 |

| 21. | Tka, N.; Kraïem, J.; Kacem, Y.; Hajri, A.; Ben Hassine, B. C. R. Chim. 2009, 12, 1066–1071. doi:10.1016/j.crci.2008.09.004 |

| 22. | Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5608–5610. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.08.008 |

| 23. | Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 252–257. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2013.12.002 |

| 14. | Gomes, P.; Araújo, J. M.; Rodrigues, M.; Vale, N.; Azevedo, Z.; Iley, J.; Chambel, P.; Morais, J.; Moreira, R. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 5551–5562. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.04.077 |

| 13. | Katritzky, A. R.; He, H.-Y.; Verma, A. K. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2002, 13, 933–938. doi:10.1016/s0957-4166(02)00220-3 |

| 17. | Ramirez, A. Agrees to Purchase Part of American Cyanamid, Wall Street Journal, June 1990, 14. |

| 34. | Kraïem, J.; Ollevier, T. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1263–1267. doi:10.1039/c6gc03589b |

| 30. | Hoshino, Y.; Oyaizu, M.; Koyanagi, Y.; Honda, K. Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 2484–2492. doi:10.1080/00397911.2012.717162 |

| 31. | Tundo, P.; Selva, M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 706–716. doi:10.1021/ar010076f |

| 32. | Rosamilia, A. E.; Aricò, F.; Tundo, P. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 1559–1562. doi:10.1021/jo701818d |

| 33. | Kraïem, J.; Ghedira, D.; Ollevier, T. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4859–4864. doi:10.1039/c6gc01394e |

| 51. | Bouzayani, N.; Talbi, W.; Marque, S.; Kacem, Y.; Ben Hassine, B. ARKIVOC 2018, No. iii, 229–239. doi:10.24820/ark.5550190.p010.297 |

| 44. | SADABS, program for scaling and correction of area detector data; Sheldrick, G. M.: University of Göttingen, Germany, 1997. |

| 45. | Blessing, R. H. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1995, 51, 33–38. doi:10.1107/s0108767394005726 |

| 46. | Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1990, 46, 467–473. doi:10.1107/s0108767390000277 |

| 47. | SHELX-TL Software Package for the Crystal Structure Determination, 5.03; Sheldrick, G. M.: Siemens Analytical X-ray Instrument Division : Madison, WI USA, 1994. |

| 48. | These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif; C19H19N3O2S, Mw = 353.43, orthorhombic, space group P212121; dimensions: a = 6.3980(3) Å, b = 14.3384(6) Å, c = 19.2989(9) Å, V = 1770.42(14) Å3; Z = 4; Dx = 1.326 Mg m−3; µ = 0.200 mm−1; 33260 reflections measured at 250 K; independent reflections: 3136 [2939 Fo > 4σ(Fo)]; data were collected up to a 2Θmax value of 50.05° (99.7% coverage). Number of variables: 231; R1 = 0.0322, wR2 = 0.0807, S = 1.078; highest residual electron density 0.15 e.Å–3; CCDC = 1829108. |

| 49. | Macrae, C. F.; Bruno, I. J.; Chisholm, J. A.; Edgington, P. R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; van de Streek, J.; Wood, P. A. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. doi:10.1107/s0021889807067908 |

| 50. | Bouzayani, N.; Marque, S.; Djelassi, B.; Kacem, Y.; Marrot, J.; Ben Hassine, B. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 6389–6398. doi:10.1039/c7nj04597b |

| 35. | Kobayashi, S.; Wakabayashi, T.; Nagayama, S.; Oyamada, H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 4559–4562. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(97)00854-x |

| 36. | Kobayashi, S.; Wakabayashi, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 5389–5392. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(98)01081-8 |

| 37. | Manabe, K.; Kobayashi, S. Synlett 1999, 547–548. doi:10.1055/s-1999-2685 |

| 38. | Manabe, K.; Mori, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 11203–11208. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(99)00642-0 |

| 39. | Kobayashi, S.; Mori, Y.; Nagayama, S.; Manabe, K. Green Chem. 1999, 1, 175–177. doi:10.1039/a904439f |

| 40. | Kobayashi, S.; Manabe, K. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 209–217. doi:10.1021/ar000145a |

| 41. | Landelle, H.; Laduree, D.; Cugnon de Servicourt, M.; Robba, M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1989, 37, 2679–2682. doi:10.1248/cpb.37.2679 |

| 42. | Suzuki, T.; Kubomura, K.; Takayama, H. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1997, 251–256. doi:10.1039/a604600b |

| 43. | Bhakuni, B. S.; Yadav, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, S. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 827–836. doi:10.1039/c3nj01105d |

| 10. | Burgess, L. E.; Meyers, A. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 9858–9859. doi:10.1021/ja00026a026 |

© 2018 Bouzayani et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)