Abstract

An alternate synthetic route to the important anticancer drug suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) from its α,ß-didehydro derivative is described. The didehydro derivative is obtained through a cross metathesis reaction between a suitable terminal alkene and N-benzyloxyacrylamide. Some of the didehydro derivatives of SAHA were preliminarily evaluated for anticancer activity towards HeLa cells. The administration of the analogues caused a significant decrease in the proliferation of HeLa cells. Furthermore, one of the analogues showed a maximum cytotoxicity with a minimum GI50 value of 2.5 µg/mL and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as some apoptotic features.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA, 1, Figure 1, vorinostat [1,2], has now emerged as a FDA approved drug for the treatment of relapsed and refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) [3]. Moreover, it also shows anticancer activity against a large number of hematological and solid malignancies [4,5]. Its anticancer activity is related to inhibition of histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) at nanomolar concentrations (IC50 < 86 nM). Although, originally recognized as a pan-inhibitor, recent studies have established that it is unable to inhibit Class IIA lysine deacetylases (HDAC/4/5/79), thus showing some selectivity profile [6,7]. Moreover, pan-inhibition is also a cause of increased concern due to adverse side effects [8]. The closely related hydroxamic acid derivative belinostat (2) is also approved for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) [9]. On the other hand, trichostatin A (3), containing an α,ß-unsaturated hydroxamic acid unit is the best known HDAC inhibitor which shows antifungal activities [10,11]. Because of the impressive level of biological activity, SAHA has received considerable attention in terms of SAR studies in the quest for a selective inhibitor and/or improved/altered biological activity [12,13]. Many of these studies have shown that minor variations in the structure of SAHA have sometimes led to significant changes in biological activity [14]. Three syntheses of this important anticancer drug have been described [15-17]. However, need for the development of alternative synthetic routes amenable for SAR studies does exist. Although a number of α,ß-dehydrohydroxamates (e.g., 2 and 3) display an useful level of bioactivity, α,ß-didehydro SAHA derivatives remain to be explored, to the best of our knowledge. Herein, we disclose two alternative synthetic routes to SAHA and preliminary biological evaluation of some α,ß-didehydro derivatives of SAHA.

Figure 1: Some hydroxamic acid-based anti-tumor drugs.

Figure 1: Some hydroxamic acid-based anti-tumor drugs.

Results and Discussion

Our synthesis of SAHA and α,ß-dehydro-SAHA derivatives relied on the identification that a successful cross metathesis between anilide 7a (Scheme 1) containing a terminal double bond and N-benzyloxyacrylamide (8) may provide access to α,ß-dehydro-SAHA derivative 10a, which may serve as precursor of both SAHA and its dehydro derivative 11a [11]. Cross metathesis (CM) between a terminal alkene and an α,ß-unsaturated carbonyl compound (or similar electron-deficient alkenes) has been used to prepare functionalized alkenes in several occasions [18-20]. We have recently reported the CM of a terminal alkene with a hydroxamic acid derivative [21]. Thus, anilide 7a was prepared by straightforward amide bond formation between aniline and 6-heptenoic acid (5) to study its cross metathesis with the hydroxamate 8. Pleasingly, use of Grubbs’ second generation catalyst [(1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)-2-imidazolidinylidene)dichloro(phenylmethylene)(tricyclohexylphosphine)ruthenium, 9a] in dichloromethane at room temperature provided the CM-product 10a in a moderate yield of 41% within 16 hours. However, raising the catalyst concentration to 5 mol % and employing elevated temperature increased the yield to 56% within 6 hours. Contrarily, the reaction in the presence of Hoveyda-Grubbs 2nd generation catalyst (HG-II, 9b, 2 mol %) in refluxing DCM was found to be much faster and better yielding (77%). The product 10a was obtained as a single geometric isomer identified as E. It may be mentioned that CM with other unsaturated carbonyl compounds has occasionally led to a mixture of isomers or even the Z-isomer as the predominant one [22]. Hydrogenation of 10a led to saturation of the double bond as well as concomitant removal of the O-benzyl group leading to SAHA (1) in an acceptable overall yield of 61% over three steps. On the other hand, removal of the O-benzyl group keeping the double bond intact proved to be problematic under a range of conditions. Pleasingly, use of BCl3 in tetrahydrofuran solvent effected the desired transformation but in a modest yield of 51%. Changing the solvent to dichloromethane and using a lower temperature proved to be beneficial and an optimized yield of 89% was achieved after experimentation. The dehydro-SAHA derivative 11a was obtained as a colourless solid. It also displayed a characteristic signal broadening in 1H NMR when recorded as dilute solution in CDCl3 indicating a conformational equilibrium. The use of DMSO-d6 resulted in a well resolved spectrum. The series of compounds 11b–f (Table 1) were similarly obtained using the three-step sequence detailed for the conversion 4a→11a in comparable overall yields of 57–66%. Short chain SAHA derivatives have occasionally displayed biological activity of comparable magnitude or even better than SAHA [23]. We therefore prepared the one-carbon shorter dehydro-SAHA derivative 11g starting from aniline and 5-hexenoic acid (6) following the three-step sequence. Compound 11g displayed similar spectroscopic behaviour to that of SAHA.

Table 1: Compounds 4–11.

| Entry | R | n | Compound (yield %) |

| 1 | H | 2 | 4a, 7a (89), 10a (77), 11a (89) |

| 2 | F | 2 | 4b, 7b (82), 10b (80), 11b (87) |

| 3 | Cl | 2 | 4c, 7c (93), 10c (78), 11c (82) |

| 4 | Br | 2 | 4d, 7d (94), 10d (77), 11d (80) |

| 5 | I | 2 | 4e, 7e (91), 10e (74), 11e (88) |

| 6 | OMe | 2 | 4f, 7f (97), 10f (78), 11f (84) |

| 7 | H | 1 | 4g, 7g (95), 10g (75), 11g (93) |

In an alternative approach, cross metathesis of 8 was first done with methyl heptenoate to prepare compound 12 in good yield. This was then hydrolyzed to get the corresponding acid 13. An amide bond formation between this acid and aniline under usual conditions provided DDSAHA derivative 10a in an overall yield of 56% over three steps.

Biological studies

Although approved for the treatment of CTCL, SAHA has been shown to display anticancer activity over a large range of other hematological and solid malignancies such as leukemia [24], lung cancer [25], cervical cancer (HeLa), breast cancer (MCF-7) [26], mesothelioma [27], B cell lymphoma (A20 cells) [28], and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC cells) [29], among others. The mechanism of biological action of SAHA in different types of cells is indeed plural in nature. Some of the common cell death pathways are intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis [30], ROS-facilitated cell death [31,32], and autophagic cell death [33]. We opted to evaluate the possible biological activity of some of the prepared dehydro-SAHA analogues along these lines. The studies were conducted with HeLa cells to determine the ability of the dehydro analogues to inhibit cell growth, to induce apoptosis, and to induce generation of ROS. Compounds 11b and 11f were arbitrarily chosen, while the shorter chain analogue 11g was selected to compare the effect of chain length, if any. Direct comparison with SAHA was made to quantify the effects shown by these three compounds in each of the experiments under identical conditions. The results are presented in Figure 2.

![[1860-5397-15-245-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-245-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Cell viability from MTT assay for SAHA, 11b, 11f and 11g on HeLa after 24 h treatment.

Figure 2: Cell viability from MTT assay for SAHA, 11b, 11f and 11g on HeLa after 24 h treatment.

The dose-dependent reduction in the viability of the cells was observed and the GI50 values were calculated (Table 2). After 24 h treatment, it was found that among the above analogues, 11b showed the highest degree of concentration-dependent increase in growth inhibition on the HeLa cell line, presenting a GI50 value of 8.9 μM (Figure 2) which was even less than SAHA (12.8 μM). However, for compounds 11f and 11g, the GI50 values were 12.65 and 165 μM, respectively. The data for compound 11f was similar to that of 11b but clearly the truncated analogue 11g is less effective.

Table 2: Percent growth inhibition valuesa at different concentration of four compounds by MTT assay [34].

| Name of sample | GI50 (µM) |

| SAHA | 12.85 |

| 11b | 8.92 |

| 11f | 12.65 |

| 11g | 165 |

aData presented from the average of three successive experiments.

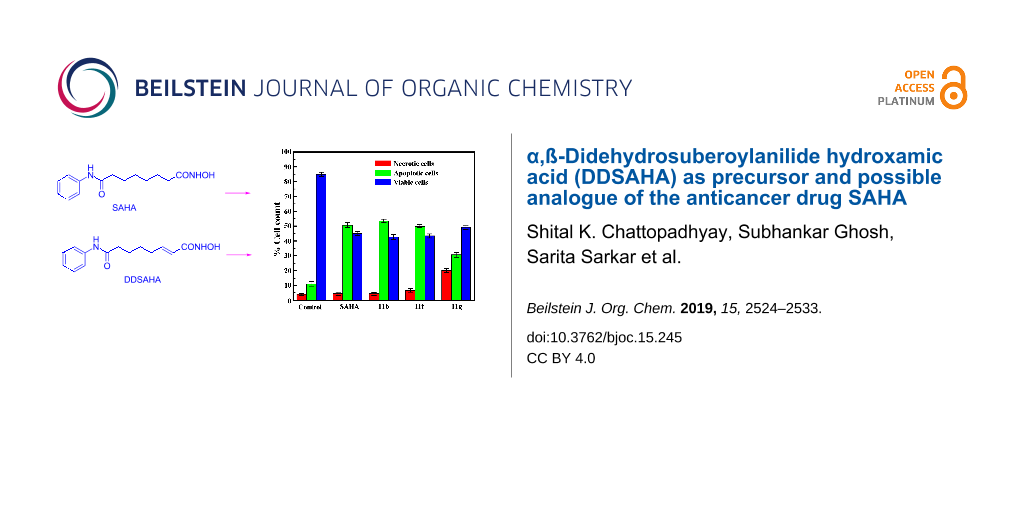

Loss of cell viability by LDH assay

LDH assays quantitatively measures lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the media from damaged cells as a biomarker for cellular cytotoxicity [35,36]. Hence, to further characterize compound-induced HeLa cell death, the LDH assay emphasizing on apoptotic index parameters were compared in both untreated (control) and with the compounds treated cells and showed 4.0 ± 0.8% necrotic, 11.0 ± 1.5% apoptotic and 85.0 ± 1.5% viable cells in the control cell line, whereas the SAHA treated cell line at GI50 dose showed 4.4 ± 1.1%, 50.6 ± 1.7% and 45.0 ± 1.3% necrotic, apoptotic and viable cells, respectively (Figure 3).

![[1860-5397-15-245-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-245-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Percent of cell death by LDH assay at a GI50 dose of SAHA, 11b, 11f and 11g after 24 h incubation along with cytotoxicity, percentage of apoptotic and necrotic cell death was also calculated. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 3: Percent of cell death by LDH assay at a GI50 dose of SAHA, 11b, 11f and 11g after 24 h incubation a...

Furthermore, treatment with compound 11b gave 4.3 ± 0.9% necrotic, 53.5 ± 1.2% apoptotic and 42.7 ± 1.8% viable cells, while compound 11f showed 6.7 ± 1.1% necrotic, 49.8 ± 1.1% apoptotic and 43.5 ± 1.4% viable cells and with compound 11g, 20.1 ± 1.4%, 30.7 ± 1.6% and 49.2 ± 1.5% necrotic, apoptotic and viable cells, respectively. The values have been collected in Table 3. The experimental protocol was repeated with the human embryonic liver cell line WRL-68 with compound 11b. It exhibited a minimal effect of cytotoxicity (≈9.1% necrotic as well as apoptotic cells, respectively), by observing the morphology of the cells under a microscope at a concentration of 15 μg/mL.

Table 3: Percent of cell death by LDH assay at GI50 dose after 24 h incubation.

| Types of cells | % Necrotic | % Apoptotic | % Viable |

| control | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 11.0 ± 1.5 | 85.0 ± 1.5 |

| SAHA | 4.4 ± 1.1 | 50.6 ± 1.7 | 45.0 ± 1.3 |

| 11b | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 53.5 ± 1.2 | 42.7 ± 1.8 |

| 11f | 6.7 ± 1.1 | 49.8 ± 1.1 | 43.5 ± 1.4 |

| 11g | 20.1 ± 1.4 | 30.7 ± 1.6 | 49.2 ± 1.5 |

aData presented from the average of three successive experiments.

ROS generation study by DCFDA (2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate) by FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorting)

The results were further complimented with ROS dependent cytotoxicity in the above cell line. ROS generation, induced by various anticancer agents plays a key role in apoptosis [37]. Cells were treated with SAHA, 11b, 11f and 11g at GI25, GI50 and GI75 concentrations for 24 h and analyzed in the presence of ROS sensitive probe DCFH-DA (dichlorodihydrofluorescein hydrate diacetate) by using FACS (Figure 4). Cellular ROS levels were found to be increased with dose. The mean fluorescent intensities for four compounds were presented in Table 4 and maximum changed intensity for 11b was observed from 20.6 ± 0.8 (control) to 90.5 ± 1.5 μM after 24 h treatment, respectively. The ROS intensity increased nearly about 4.4-fold relative to the control. Thus, it may be concluded that 11b induced apoptosis in HeLa cells via a ROS-mediated pathway. Henceforth detailed apoptotic induction ability of compound 11b has been studied since it was the most cytotoxic among all.

Table 4: Comparison between quantitative assays of ROSa generation induced by four compounds by DCFH-DA in HeLa cells through flow cytometric analysis.

| Added concentrations of compounds (μM) | Percent ROS | |||

| SAHA | 11b | 11f | 11g | |

| control | 20.3 ± 0.9 | 20.6 ± 0.8 | 20.4 ± 0.8 | 20.4 ± 0.7 |

| GI25 | 32.8 ± 1.2 | 38.9 ± 1.2 | 28.7 ± 1.2 | 30.6 ± 1.6 |

| GI50 | 60.9 ± 1.4 | 69.4 ± 1.1 | 52.4 ± 1.5 | 33.1 ± 1.2 |

| GI75 | 83.4 ± 1.7 | 90.5 ± 1.5 | 86.9 ± 1.6 | 34.5 ± 1.5 |

aAverage of three individual experiments at same conditions.

FITC (fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate)–annexin V/PI flow cytometry of HepG2 cells

On HeLa cells, the efficacy of 11b was measured through the application of other apoptotic parameters like phosphatidylserine (PS) externalization, a known marker of an early stage of apoptosis following our previously reported procedure [37]. The quantitative results of bivariate FITC-Annexin V/PI FCM of HeLa cells after treatment with 11b at different concentrations (at 8.9, and 14.2 μM, respectively) are presented in Figure 5 [38]. The lower right quadrant represents the apoptotic cells, FITC–annexin V positive and PI negative, which depicts Annexin V binding to PS and cytoplasmic membrane integrity. The FITC+/PI− apoptotic cell population increased gradually from 4.6 ± 0.8% of control to 76.8 ± 1.3% after 24 h drug treatment which is presented in Table 5. Thus, FITC–Annexin V/PI FCM and LDH assays (vide supra) both supported higher percentage of apoptosis in comparison to the negligible necrosis in HeLa cells treated with 11b.

![[1860-5397-15-245-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-245-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: The quantitative results of bivariate FITC-Annexin V/PI FCM of HeLa cells after treatment with 11b for different concentrations (at 8.9, and 14.2 µM, respectively).

Figure 5: The quantitative results of bivariate FITC-Annexin V/PI FCM of HeLa cells after treatment with 11b ...

Table 5: Percent apoptotic cellsa in presence and absence of 11b by FITC-Annexin-V/PI staining by FACs analysis.

| Concentration | Percentage of apoptotic cells |

| control | 4.6 ± 0.8 |

| 8.9 µM | 47.3 ± 1.5 |

| 14.2 µM | 76.8 ± 1.3 |

aData presented from average of three successive experiments.

Fluorescence microscopic images of Hela cells using different staining techniques and DNA ladder formation

Hela cells with DAPI staining revealed a significant increase in nucleosomal fragmentation and nuclear condensation in 11b treated cells with increasing doses (Figure 6 upper panel) [39].

![[1860-5397-15-245-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-245-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Fluorescence microscopic images of 11b at different concentrations (8.9, and 14.2 µM, respectively) of the HeLa cells after 24 h treatment. HeLa cells with (A) DAPI staining, (B) JC-1 probe and (C) comet assay revealed significant change in control and treated conditions.

Figure 6: Fluorescence microscopic images of 11b at different concentrations (8.9, and 14.2 µM, respectively)...

Furthermore, a cellular functional assay by JC-1 probe, a voltage sensitive fluorescent cationic dye, exhibits membrane potential dependent accumulation in mitochondria, indicated by a fluorescence emission shift from red to green. The exposure of 11b to the cells caused remarkable loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, hence the fluorescence gradually shifted from red to green as the membrane potential (Ψm) decreased (Figure 6 middle panel).

One of the later steps in apoptosis is ultimately the DNA fragmentation, a process which results from the endonuclease activation during apoptosis. Hence, we further characterized the apoptotic phenomena in HeLa cells by the formation of comet tails (Figure 6, lower panel) and DNA gel electrophoresis (Figure 7). Apoptotic hallmark of chromosomal DNA laddering was clearly evident in HeLa cells, treated with different doses of the compound as compared to untreated cells. Thus these two assays comet formation and DNA laddering indicated DNA damage during the apoptotic induction.

![[1860-5397-15-245-7]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-245-7.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 7: DNA Ladder formation in a gel electrophoresis study of 11b at different concentrations (at 8.9, and 14.2 µM, respectively) on HeLa after 24 h treatment.

Figure 7: DNA Ladder formation in a gel electrophoresis study of 11b at different concentrations (at 8.9, and...

Conclusion

We have demonstrated two alternative syntheses of the important anticancer drug SAHA through cross-metathesis reaction with a hitherto unexplored α,ß-didehydrohydroxamate derivative. This has also led to the synthesis of a series of α,ß-didehydo-SAHA derivatives as potential analogues of SAHA. Preliminary biological evaluation of three such analogues involving the measurement of GI50 values against Hela cells and ROS-mediated apoptosis as possible mechanism of action of these analogues, have shown that the data obtained for one compound (11b) are very close to those of SAHA for the cell line studied. Further studies are required to fully explore its activity profile. Moreover, their HDAC inhibitory effects remain to be evaluated. Studies will be continued along these directions [40-44].

Experimental

Procedure for the synthesis of anilides 7a–g

These were prepared following the procedure described for 7a [45]. DCC (206 mg, 0.7 mmol) was added portionwise to a stirred solution of the acid 5 (83 mg, 0.65 mmol) in dry DCM (5 mL) at 0 °C during 15 minutes. Then a solution of aniline (50 mg, 0.54 mmol) and N-methylmorpholine (55 mg, 60 μL, 0.54 mmol) in dry DCM (3 mL) was added dropwise over 10 min to the solution of the acid at the same temperature. The reaction mixture was allowed to come to rt and stirred for 16 h. It was then diluted with DCM (20 mL) and the combined organic solution was washed successively with a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 (2 × 15 mL), HCl (2 N, 2 × 10 mL), H2O (1 × 20 mL), brine (1 × 20 mL), and then dried (Na2SO4).It was then concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using a mixture of hexane/ethyl acetate (85:15) as eluent to provide the product 7a (98 mg, 89%) as colourless viscous liquid [45]. IR (neat): 3267, 3076, 1666, 1579 cm−1; 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.33 (brs, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.10 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.84–5.74 (m, 1H), 5.03–4.95 (m, 2H), 2.36 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.06 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.72 (quin, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.44 (quin, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.1, 138.4, 138.2, 128.9, 124.2, 120.2, 114.8, 37.4, 33.5, 28.3, 25.2; anal. calcd for C13H17NO; C, 76.81; H, 8.43; N, 6.89; found: C, 76.99; H, 8.68; N, 6.72.

General procedure for cross metathesis

This was done following our earlier procedure [21]. Grubbs’ second generation catalyst HG-II (9b, 5 mg, 2 mol %), was added to a stirred solution of the olefin 7a (149 mg, 0.73 mmol) and olefin 8 (66 mg, 0.37 mmol) in anhydrous and degassed DCM (3 mL) at rt and the reaction mixture was heated to reflux for 3 h under an argon atmosphere. It was allowed to cool to room temperature and then concentrated in vacuo. The residual mass was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (CHCl3/MeOH 98:2) to provide the coupled product 10a (101 mg, 77%) as colourless solid. Mp 148–150 °C; IR (neat): 3296, 3211, 2926, 2858, 1663, 1639 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.04 (s, 1H), 9.82 (s, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (brs, 5H), 7.21 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (dt, J = 15.2, 8 Hz, 1H), 5.66 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 4.75 (s, 2H), 2.24 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.10 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.52 (quin, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.35 (quin, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.6, 163.3, 144.1, 139.7, 136.5, 129.2, 129.1, 128.8, 123.4, 121.4, 119.5, 77.4, 36.6, 31.6, 27.8, 25.1; anal. calcd for C21H24N2O3; C, 71.57; H, 6.86; N, 7.95; found: C, 71.79; H, 7.01; N, 8.22.

Synthesis of SAHA from DDSAHA

Following our earlier procedure [21], CM product 10a (50 mg, 0.14 mmol) was taken up in MeOH (3 mL) containing 1 drop of TFA. Then Pd(OH)2-C (10 mg) was added and the solution was degassed several times. A hydrogen-filled balloon was attached and the heterogeneous mixture was vigorously stirred at rt for 2 h. It was filtered through Celite, the filter cake was washed with methanol (5 mL) and the combined filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (CHCl3/MeOH 9:1) to provide SAHA (34 mg, 91%) as colorless solid. Mp 158–159 °C; IR (neat): 3267, 2927, 2854, 1667, 1645 cm–1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.29 (s, 1H), 9.80 (s, 1H), 8.63 (brs, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 2.22 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.87 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.51 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.42 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.23–1.16 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.7, 169.6, 139.8, 129.1, 123.4, 119.5, 36.8, 32.7, 28.9, 25.5.

General procedure for the synthesis of α,ß-didehydro-SAHA derivatives 11a–g

A BCl3 solution (0.30 mL, 1 M in heptane, 1.2 equiv) was added drop wise to a solution of 10a (90 mg, 0.25 mmol) in DCM (4 mL) at 0 °C under argon and was stirred for 5 minutes. The reaction mixture was allowed to come to rt while stirring and it was further stirred for an additional 2 h at room temperature. The mixture was then quenched with saturated NaHCO3 solution (2.5 mL) and extracted with DCM (2 × 25 mL). The organic layer was separated, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using a mixture of CHCl3/MeOH (19:1) to provide the product dehydro-SAHA 11a (59 mg, 89%) as a colourless solid. Mp 154–158 °C; IR (neat): 3287, 3193, 2939, 2854, 1670, 1633 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.49 (s, 1H), 9.81 (s, 1H), 8.81 (brs, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (dt, J = 15.6, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 5.68 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 2.24 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.09 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.52 (quin, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.40–1.32 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.6, 163.2, 142.5, 139.7, 129.1, 123.4, 121.8, 119.5, 36.6, 31.5, 27.9, 25.1; anal. calcd for C14H18N2O3; C, 64.10; H, 6.92; N, 10.68; found: C, 64.24; H, 7.08; N, 10.54.

Percent growth inhibition: MTT assay

The percentage of cell viability and the GI50 (50% growth inhibition) values of SAHA, 11b, 11f, 11g for HeLa cells (cervical carcinoma) were calculated by MTT (1 mg/mL of the tetrazolium dye, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4) assay [34]. Cells without any drug treatment were considered as control. The GI50 was calculated by using the following equation.

Where, T is the optical density of the test well after 24 hours of drug exposure, To is the optical density at time zero and C is the optical density of control. The experiment was repeated three times and the average value was considered.

Loss of cell viability by LDH assay

LDH assays quantitatively measures lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the media from damaged cells as a biomarker for cellular cytotoxicity [35,36]. LDH or lactate dehydrogenase activity was measured quantitatively for both control and most active 11b treated cells according to a literature protocol. The percent apoptotic cells as well as necrotic cell deaths were determined as follows:

The floating cells were collected from the culture media by centrifugation (3000 rpm) at 4 °C for 4 min, and here the LDH content from the pellets was determined as an index of apoptotic cell death (LDHp). LDHe was marked as an index of necrotic cell death from the released extracellular LDH in the culture supernatant, and the in the adherent viable count LDHi was marked as intracellular LDH. HeLa cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and treated with 11b of 2.5 and 4.0 μg/mL concentrations at 37 °C for 24 h.

Quantification of ROS by FACS

Cells (2 × 105) were treated with SAHA, 11b, 11f, 11g at GI25, GI50 and GI75 concentrations for 24 h and the levels of intracellular ROS were assessed by flow cytometry after incubating with DCFH-DA (25 μM) (2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate) for 30 min at 37 °C as described previously [38].

Estimation of DNA damage (comet assay and DNA gel electrophoresis)

Comet assay was performed on HeLa cells by single cell gel electrophoresis as reported by Liao et al. and the examination was performed with a fluorescence microscope [46]. Comet assays consist of mainly the following steps: slide preparation and cell lysis to liberate the DNA, DNA unwinding, electrophoresis, neutralization of the alkali, DNA staining. Dye used for electrophoresis: From 10 mg/mL stock solution of ethidium bromide 5 μL was added per 100 mL gel solution for a final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL. Comet assays for detection of DNA damage of both control and 11b treated HeLa cells were detected by single cell gel electrophoresis.

We isolated DNA of HeLa cells by a standardized salting out method according to Miller et al. [47] and performed DNA gel electrophoresis in 1.2% agarose gel.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Analytical data of all new compounds as well as copies of their 1H and 13C NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 6.7 MB | Download |

References

-

Marks, P. A.; Breslow, R. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 84–90. doi:10.1038/nbt1272

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Spratlin, J. L.; Pitts, T. M.; Kulikowski, G. N.; Morelli, M. P.; Tentler, J. J.; Serkova, N. J.; Eckhardt, S. G. Anticancer Res. 2011, 31, 1093–1103.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kavanaugh, S. A.; White, L. A.; Kolesar, J. M. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 793–797. doi:10.2146/ajhp090247

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kelly, W. K.; O'Connor, O. A.; Krug, L. M.; Chiao, J. H.; Heaney, M.; Curley, T.; MacGregore-Cortelli, B.; Tong, W.; Secrist, J. P.; Schwartz, L.; Richardson, S.; Chu, E.; Olgac, S.; Marks, P. A.; Scher, H.; Richon, V. M. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3923–3931. doi:10.1200/jco.2005.14.167

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Roche, J.; Bertrand, P. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 121, 451–483. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.05.047

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bantscheff, M.; Hopf, C.; Savitski, M. M.; Dittmann, A.; Grandi, P.; Michon, A.-M.; Schlegl, J.; Abraham, Y.; Becher, I.; Bergamini, G.; Boesche, M.; Delling, M.; Dümpelfeld, B.; Eberhard, D.; Huthmacher, C.; Mathieson, T.; Poeckel, D.; Reader, V.; Strunk, K.; Sweetman, G.; Kruse, U.; Neubauer, G.; Ramsden, N. G.; Drewes, G. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 255–265. doi:10.1038/nbt.1759

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bradner, J. E.; West, N.; Grachan, M. L.; Greenberg, E. F.; Haggarty, S. J.; Warnow, T.; Mazitschek, R. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 238–243. doi:10.1038/nchembio.313

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hornig, E.; Heppt, M. V.; Graf, S. A.; Ruzicka, T.; Berking, C. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 25, 831–838. doi:10.1111/exd.13089

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Plumb, J. A.; Finn, P. W.; Williams, R. J.; Bandara, M. J.; Romero, M. R.; Watkins, C. J.; La Thangue, N. B.; Brown, R. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 721–728.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marks, P. A.; Richon, V. M.; Breslow, R.; Rifkind, R. A. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2001, 13, 477–483. doi:10.1097/00001622-200111000-00010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sanaei, M.; Kavoosi, F.; Roustazadeh, A.; Golestan, F. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 141–146. doi:10.14218/jcth.2018.00002

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Walton, J. W.; Cross, J. M.; Riedel, T.; Dyson, P. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 9186–9190. doi:10.1039/c7ob02339a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Negmeldin, A. T.; Padige, G.; Bieliauskas, A. V.; Pflum, M. K. H. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 281–286. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00124

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oger, F.; Lecorgne, A.; Sala, E.; Nardese, V.; Demay, F.; Chevance, S.; Desravines, D. C.; Aleksandrova, N.; Guével, R. L.; Lorenzi, S.; Beccari, A. R.; Barath, P.; Hart, D. J.; Bondon, A.; Carettoni, D.; Simonneaux, G.; Salbert, G. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 1937–1950. doi:10.1021/jm901561u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gore, V. G.; Patil, M. S.; Bhalerao, R. A.; Mande, H. M.; Mekde, S. G. Process for the preparation of Vorinostat. U.S. Patent US9,162,974B2, Oct 20, 2015.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stowell, J. C.; Huot, R. I.; Van Voast, L. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 1411–1413. doi:10.1021/jm00008a020

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gediya, L. K.; Chopra, P.; Purushottamachar, P.; Maheshwari, N.; Njar, V. C. O. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5047–5051. doi:10.1021/jm058214k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

O'Leary, D. J.; O'Neil, G. W. Cross-Metathesis. In Handbook of Metathesis; Grubbs, R. H.; Wenzel, A. G.; O'Leary, D. J.; Khosravi, E., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2015; Vol. 2, pp 171–294.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Żukowska, K.; Grela, K. Cross Metathesis. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis II; Knochel, P.; Molander, G. A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2014; Vol. 5, pp 1257–1301. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-097742-3.00527-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zukowska, K.; Grela, K. Cross Metathesis. In Olefin Metathesis-Theory and Practice; Grela, K., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ,, 2014; pp 37–83. doi:10.1002/9781118711613.ch2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chattopadhyay, S. K.; Ghosh, S.; Sil, S. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 3070–3075. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.285

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Bidange, J.; Fischmeister, C.; Bruneau, C.; Dubois, J.-L.; Couturier, J.-L. Monatsh. Chem. 2015, 146, 1107–1113. doi:10.1007/s00706-015-1480-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fass, D. M.; Shah, R.; Ghosh, B.; Hennig, K.; Norton, S.; Zhao, W.-N.; Reis, S. A.; Klein, P. S.; Mazitschek, R.; Maglathlin, R. L.; Lewis, T. A.; Haggarty, S. J. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 39–42. doi:10.1021/ml1001954

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Garcia-Manero, G.; Yang, H.; Bueso-Ramos, C.; Ferrajoli, A.; Cortes, J.; Wierda, W. G.; Faderl, S.; Koller, C.; Morris, G.; Rosner, G.; Loboda, A.; Fantin, V. R.; Randolph, S. S.; Hardwick, J. S.; Reilly, J. F.; Chen, C.; Ricker, J. L.; Secrist, J. P.; Richon, V. M.; Frankel, S. R.; Kantarjian, H. M. Blood 2008, 111, 1060–1066. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-06-098061

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karelia, N.; Desai, D.; Hengst, J. A.; Amin, S.; Rudrabhatla, S. V.; Yun, J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6816–6819. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.113

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vickers, C. J.; Olsen, C. A.; Leman, L. J.; Ghadiri, M. R. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 505–508. doi:10.1021/ml300081u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hurwitz, J. L.; Stasik, I.; Kerr, E. M.; Holohan, C.; Redmond, K. M.; McLaughlin, K. M.; Busacca, S.; Barbone, D.; Broaddus, V. C.; Gray, S. G.; O’Byrne, K. J.; Johnston, P. G.; Fennell, D. A.; Longley, D. B. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1096–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.009

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, B.; Yu, D.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Wu, G.; Liu, H. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 5051–5061. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-3156-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gillenwater, A. M.; Zhong, M.; Lotan, R. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 2967–2975. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.mct-04-0344

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bolden, J. E.; Peart, M. J.; Johnstone, R. W. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5, 769–784. doi:10.1038/nrd2133

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rosato, R. R.; Grant, S. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2005, 9, 809–824. doi:10.1517/14728222.9.4.809

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gillenwater, A. M.; Zhong, M.; Lotan, R. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 2967–2975. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.mct-04-0344

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Marks, P. A.; Jiang, X. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 18030–18035. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408345102

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mosmann, T. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kim, Y.-M.; Talanian, R. V.; Billiar, T. R. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 31138–31148. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.49.31138

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Smith, S. M.; Wunder, M. B.; Norris, D. A.; Shellman, Y. G. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026908

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sarkar, S.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Bhadra, K. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2016, 258, 142–152. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2016.08.024

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Böhmer, R. H.; Trinkle, L. S.; Staneck, J. L. Cytometry 1992, 13, 525–531. doi:10.1002/cyto.990130512

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chatterjee, S.; Mallick, S.; Buzzetti, F.; Fiorillo, G.; Syeda, T. M.; Lombardi, P.; Saha, K. D.; Kumar, G. S. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 90632–90644. doi:10.1039/c5ra17214d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pahari, A. K.; Mukherjee, J. P.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 7185–7191. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.07.045

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mukherjee, J. P.; Sil, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 739–742. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.01.005

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mukherjee, J. P.; Sil, S.; Pahari, A. K.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Synthesis 2016, 48, 1181–1190. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1561561

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mukherjee, J.; Sil, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 2487–2492. doi:10.3762/bjoc.11.270

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chattopadhyay, S. K.; Sil, S.; Mukherjee, J. P. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2153–2156. doi:10.3762/bjoc.13.214

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hernandez, E.; Hoberg, H. J. Organomet. Chem. 1987, 328, 403–412. doi:10.1016/0022-328x(87)80256-5

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Liao, W.; McNutt, M. A.; Zhu, W.-G. Methods 2009, 48, 46–53. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.02.016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Miller, S. A.; Dykes, D. D.; Polesky, H. F. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 1215. doi:10.1093/nar/16.3.1215

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 37. | Sarkar, S.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Bhadra, K. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2016, 258, 142–152. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2016.08.024 |

| 38. | Böhmer, R. H.; Trinkle, L. S.; Staneck, J. L. Cytometry 1992, 13, 525–531. doi:10.1002/cyto.990130512 |

| 39. | Chatterjee, S.; Mallick, S.; Buzzetti, F.; Fiorillo, G.; Syeda, T. M.; Lombardi, P.; Saha, K. D.; Kumar, G. S. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 90632–90644. doi:10.1039/c5ra17214d |

| 1. | Marks, P. A.; Breslow, R. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 84–90. doi:10.1038/nbt1272 |

| 2. | Spratlin, J. L.; Pitts, T. M.; Kulikowski, G. N.; Morelli, M. P.; Tentler, J. J.; Serkova, N. J.; Eckhardt, S. G. Anticancer Res. 2011, 31, 1093–1103. |

| 8. | Hornig, E.; Heppt, M. V.; Graf, S. A.; Ruzicka, T.; Berking, C. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 25, 831–838. doi:10.1111/exd.13089 |

| 23. | Fass, D. M.; Shah, R.; Ghosh, B.; Hennig, K.; Norton, S.; Zhao, W.-N.; Reis, S. A.; Klein, P. S.; Mazitschek, R.; Maglathlin, R. L.; Lewis, T. A.; Haggarty, S. J. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 39–42. doi:10.1021/ml1001954 |

| 35. | Kim, Y.-M.; Talanian, R. V.; Billiar, T. R. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 31138–31148. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.49.31138 |

| 36. | Smith, S. M.; Wunder, M. B.; Norris, D. A.; Shellman, Y. G. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026908 |

| 6. | Bantscheff, M.; Hopf, C.; Savitski, M. M.; Dittmann, A.; Grandi, P.; Michon, A.-M.; Schlegl, J.; Abraham, Y.; Becher, I.; Bergamini, G.; Boesche, M.; Delling, M.; Dümpelfeld, B.; Eberhard, D.; Huthmacher, C.; Mathieson, T.; Poeckel, D.; Reader, V.; Strunk, K.; Sweetman, G.; Kruse, U.; Neubauer, G.; Ramsden, N. G.; Drewes, G. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 255–265. doi:10.1038/nbt.1759 |

| 7. | Bradner, J. E.; West, N.; Grachan, M. L.; Greenberg, E. F.; Haggarty, S. J.; Warnow, T.; Mazitschek, R. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 238–243. doi:10.1038/nchembio.313 |

| 24. | Garcia-Manero, G.; Yang, H.; Bueso-Ramos, C.; Ferrajoli, A.; Cortes, J.; Wierda, W. G.; Faderl, S.; Koller, C.; Morris, G.; Rosner, G.; Loboda, A.; Fantin, V. R.; Randolph, S. S.; Hardwick, J. S.; Reilly, J. F.; Chen, C.; Ricker, J. L.; Secrist, J. P.; Richon, V. M.; Frankel, S. R.; Kantarjian, H. M. Blood 2008, 111, 1060–1066. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-06-098061 |

| 38. | Böhmer, R. H.; Trinkle, L. S.; Staneck, J. L. Cytometry 1992, 13, 525–531. doi:10.1002/cyto.990130512 |

| 4. | Kelly, W. K.; O'Connor, O. A.; Krug, L. M.; Chiao, J. H.; Heaney, M.; Curley, T.; MacGregore-Cortelli, B.; Tong, W.; Secrist, J. P.; Schwartz, L.; Richardson, S.; Chu, E.; Olgac, S.; Marks, P. A.; Scher, H.; Richon, V. M. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3923–3931. doi:10.1200/jco.2005.14.167 |

| 5. | Roche, J.; Bertrand, P. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 121, 451–483. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.05.047 |

| 21. | Chattopadhyay, S. K.; Ghosh, S.; Sil, S. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 3070–3075. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.285 |

| 21. | Chattopadhyay, S. K.; Ghosh, S.; Sil, S. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 3070–3075. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.285 |

| 3. | Kavanaugh, S. A.; White, L. A.; Kolesar, J. M. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 793–797. doi:10.2146/ajhp090247 |

| 22. | Bidange, J.; Fischmeister, C.; Bruneau, C.; Dubois, J.-L.; Couturier, J.-L. Monatsh. Chem. 2015, 146, 1107–1113. doi:10.1007/s00706-015-1480-1 |

| 34. | Mosmann, T. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4 |

| 14. | Oger, F.; Lecorgne, A.; Sala, E.; Nardese, V.; Demay, F.; Chevance, S.; Desravines, D. C.; Aleksandrova, N.; Guével, R. L.; Lorenzi, S.; Beccari, A. R.; Barath, P.; Hart, D. J.; Bondon, A.; Carettoni, D.; Simonneaux, G.; Salbert, G. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 1937–1950. doi:10.1021/jm901561u |

| 11. | Sanaei, M.; Kavoosi, F.; Roustazadeh, A.; Golestan, F. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 141–146. doi:10.14218/jcth.2018.00002 |

| 45. | Hernandez, E.; Hoberg, H. J. Organomet. Chem. 1987, 328, 403–412. doi:10.1016/0022-328x(87)80256-5 |

| 12. | Walton, J. W.; Cross, J. M.; Riedel, T.; Dyson, P. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 9186–9190. doi:10.1039/c7ob02339a |

| 13. | Negmeldin, A. T.; Padige, G.; Bieliauskas, A. V.; Pflum, M. K. H. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 281–286. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00124 |

| 18. | O'Leary, D. J.; O'Neil, G. W. Cross-Metathesis. In Handbook of Metathesis; Grubbs, R. H.; Wenzel, A. G.; O'Leary, D. J.; Khosravi, E., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2015; Vol. 2, pp 171–294. |

| 19. | Żukowska, K.; Grela, K. Cross Metathesis. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis II; Knochel, P.; Molander, G. A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2014; Vol. 5, pp 1257–1301. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-097742-3.00527-9 |

| 20. | Zukowska, K.; Grela, K. Cross Metathesis. In Olefin Metathesis-Theory and Practice; Grela, K., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ,, 2014; pp 37–83. doi:10.1002/9781118711613.ch2 |

| 21. | Chattopadhyay, S. K.; Ghosh, S.; Sil, S. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 3070–3075. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.285 |

| 10. | Marks, P. A.; Richon, V. M.; Breslow, R.; Rifkind, R. A. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2001, 13, 477–483. doi:10.1097/00001622-200111000-00010 |

| 11. | Sanaei, M.; Kavoosi, F.; Roustazadeh, A.; Golestan, F. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 141–146. doi:10.14218/jcth.2018.00002 |

| 40. | Pahari, A. K.; Mukherjee, J. P.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 7185–7191. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.07.045 |

| 41. | Mukherjee, J. P.; Sil, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 739–742. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.01.005 |

| 42. | Mukherjee, J. P.; Sil, S.; Pahari, A. K.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Synthesis 2016, 48, 1181–1190. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1561561 |

| 43. | Mukherjee, J.; Sil, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. K. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 2487–2492. doi:10.3762/bjoc.11.270 |

| 44. | Chattopadhyay, S. K.; Sil, S.; Mukherjee, J. P. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2153–2156. doi:10.3762/bjoc.13.214 |

| 9. | Plumb, J. A.; Finn, P. W.; Williams, R. J.; Bandara, M. J.; Romero, M. R.; Watkins, C. J.; La Thangue, N. B.; Brown, R. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 721–728. |

| 15. | Gore, V. G.; Patil, M. S.; Bhalerao, R. A.; Mande, H. M.; Mekde, S. G. Process for the preparation of Vorinostat. U.S. Patent US9,162,974B2, Oct 20, 2015. |

| 16. | Stowell, J. C.; Huot, R. I.; Van Voast, L. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 1411–1413. doi:10.1021/jm00008a020 |

| 17. | Gediya, L. K.; Chopra, P.; Purushottamachar, P.; Maheshwari, N.; Njar, V. C. O. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5047–5051. doi:10.1021/jm058214k |

| 45. | Hernandez, E.; Hoberg, H. J. Organomet. Chem. 1987, 328, 403–412. doi:10.1016/0022-328x(87)80256-5 |

| 27. | Hurwitz, J. L.; Stasik, I.; Kerr, E. M.; Holohan, C.; Redmond, K. M.; McLaughlin, K. M.; Busacca, S.; Barbone, D.; Broaddus, V. C.; Gray, S. G.; O’Byrne, K. J.; Johnston, P. G.; Fennell, D. A.; Longley, D. B. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1096–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.009 |

| 25. | Karelia, N.; Desai, D.; Hengst, J. A.; Amin, S.; Rudrabhatla, S. V.; Yun, J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6816–6819. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.113 |

| 46. | Liao, W.; McNutt, M. A.; Zhu, W.-G. Methods 2009, 48, 46–53. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.02.016 |

| 26. | Vickers, C. J.; Olsen, C. A.; Leman, L. J.; Ghadiri, M. R. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 505–508. doi:10.1021/ml300081u |

| 47. | Miller, S. A.; Dykes, D. D.; Polesky, H. F. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 1215. doi:10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 |

| 35. | Kim, Y.-M.; Talanian, R. V.; Billiar, T. R. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 31138–31148. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.49.31138 |

| 36. | Smith, S. M.; Wunder, M. B.; Norris, D. A.; Shellman, Y. G. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026908 |

| 37. | Sarkar, S.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Bhadra, K. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2016, 258, 142–152. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2016.08.024 |

| 33. | Shao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Marks, P. A.; Jiang, X. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 18030–18035. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408345102 |

| 34. | Mosmann, T. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4 |

| 30. | Bolden, J. E.; Peart, M. J.; Johnstone, R. W. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5, 769–784. doi:10.1038/nrd2133 |

| 31. | Rosato, R. R.; Grant, S. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2005, 9, 809–824. doi:10.1517/14728222.9.4.809 |

| 32. | Gillenwater, A. M.; Zhong, M.; Lotan, R. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 2967–2975. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.mct-04-0344 |

| 28. | Yang, B.; Yu, D.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Wu, G.; Liu, H. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 5051–5061. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-3156-1 |

| 29. | Gillenwater, A. M.; Zhong, M.; Lotan, R. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 2967–2975. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.mct-04-0344 |

© 2019 Chattopadhyay et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)

![[1860-5397-15-245-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-245-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)