Abstract

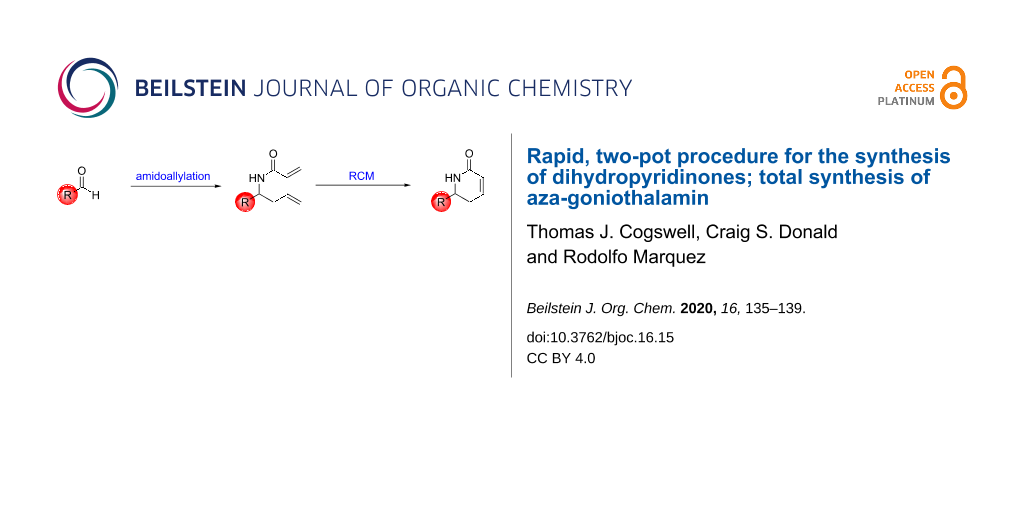

A fast, protecting-group-free synthesis of dihydropyridinones has been developed. Starting from commercially available aldehydes, a novel one-pot amidoallylation gave access to diene compounds in good yields. Ring-closing metathesis conditions were then employed to produce the target dihydropyridinones efficiently and in high yields.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Six-membered nitrogen heterocycles are prevalent in many naturally occurring and biologically active compounds. As a result, their synthesis has received extensive research and wide spread publication in the literature [1-6]. Dihydropyridinones are an important subclass of heterocycles, which often feature both as useful intermediates, and as interesting species in their own right [7-13].

The relevance of dihydropyridones as lead compounds is exemplified by the detailed investigations into the synthesis and biological evaluation of aza-goniothalamin 1 and its analogues (Figure 1). (R)-(+)-Goniothalamin 2, a natural product isolated in 1967, was shown to be cytotoxic against human leukaemia, kidney, ovarian and prostate cancer cell lines (IC50 = 25 µM, U251 cell line) [14-16]. In an attempt to increase the bioavailability of (R)-(+)-goniothalamin 2, aza-goniothalamin 1 was designed and synthesised; however, aza-goniothalamin 1 was found to have significantly lower biological activity compared to the parent compound (IC50 = 942 µM, U251 cell line) [15,16]. However, Pilli and co-workers were able to demonstrate that acylation of aza-goniothalamin 1 yielded analogues such as compound 3 with significantly improved biological profiles (IC50 = 11 µM, U251 cell line, Figure 1). Thus, a path for the generation of a new class of potential anticancer agents based on the aza-goniothalamin framework was determined [17,18].

Figure 1: Aza-goniothalamin 1, (R)-(+)-goniothalamin 2 and acylated aza-goniothalamin analogue 3 [14-18].

Figure 1: Aza-goniothalamin 1, (R)-(+)-goniothalamin 2 and acylated aza-goniothalamin analogue 3 [14-18].

Results and Discussion

Our approach to the synthesis of the dihydropyridinone framework was inspired by the work carried out by Veenstra and co-workers, who developed a one-pot, three-component reaction to produce protected homoallylic amines 4 (Scheme 1) [19].

Scheme 1: One pot synthesis of benzyl carbamate 4 reported by Veenstra and co-workers [19].

Scheme 1: One pot synthesis of benzyl carbamate 4 reported by Veenstra and co-workers [19].

It was reasoned that adaptation of the Veenstra protocol would allow us to introduce a second alkene unit during the same process, thus generating a ring-closing metathesis precursor in a single step. This general strategy towards nitrogen heterocycles has been utilized in several reports [20-23], including asymmetric variants [24,25], but in these cases the ring-closing metathesis precursor was always generated in multiple steps.

In order to test this hypothesis, acrylamide was used in an analogous manner to the carbamates employed by Veenstra (Scheme 1) [19]. In our initial attempts, the solvent was changed from dichloromethane to acetonitrile due to solubility issues with the acrylamide and the postulated imine intermediate. The reaction proved sluggish, taking four days to reach completion; however, the dialkene 5 was isolated in a very encouraging 66% yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Formation of diene 5 in 66% through a one pot, three component coupling.

Scheme 2: Formation of diene 5 in 66% through a one pot, three component coupling.

In an attempt to increase the yield of the overall process, the reaction conditions were optimized to reach complete formation of imine 6, before treatment with allyltrimethylsilane to generate the desired product. This stepwise addition was successful in affording an improved 88% yield of diene 5 as well as significantly reducing the overall reaction time (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3: Optimized conditions for the synthesis of diene 5.

Scheme 3: Optimized conditions for the synthesis of diene 5.

Treatment of diene 5 under ring-closing metathesis conditions, using Grubbs I catalyst, then proceeded to generate the target dihydropyridinone 7 in excellent yield (Scheme 4) [20-23,26].

Scheme 4: Ring-closing metathesis reaction of diene 5 to yield dihydropyridone 7 [20-23].

Scheme 4: Ring-closing metathesis reaction of diene 5 to yield dihydropyridone 7 [20-23].

The scope of this concise two-pot methodology was then investigated by using a variety of different aldehydes as starting materials (Figure 2). The electron-donating aromatic substrates and the aliphatic units gave consistently high results over the 2-pot process, producing dihydropyridinones 9a and 9c–e in high yields. The electron-withdrawing substituted aromatic starting materials on the other hand, gave a low yield in the first step, which we believe was due to poor solubility of the imine intermediate. In contrast, the ring-closing metathesis reaction worked nicely to give 9b in 99% yield.

Figure 2: Extension of the two-pot methodology to include a variety of different aldehyde starting materials.

Figure 2: Extension of the two-pot methodology to include a variety of different aldehyde starting materials.

Having demonstrated the versatility of our approach, the synthesis of racemic aza-goniothalamin was attempted. Our synthesis began with cinnamaldehyde (Scheme 5), which was condensed with acrylamide under the same conditions described above. Rewardingly, Hosomi–Sakurai allylation of the conjugated imine intermediate proceeded to afford the desired diene 10 in working yield (35%). The formation of diene 10 is significant as the corresponding α,β-enones and α,β-enals undergo exclusive conjugate addition under Hosomi–Sakurai conditions [27,28]. Ring-closing metathesis of diene 10 then proceeded in good yield (68%) to complete a fast and efficient, protecting-group-free, two-pot procedure for the racemic synthesis of aza-goniothalamin 1.

Scheme 5: Total synthesis of aza-goniothalamin 1.

Scheme 5: Total synthesis of aza-goniothalamin 1.

Conclusion

In summary, a two-pot, protecting-group-free procedure for the synthesis of dihydropyridinones has been developed. The process requires a one-pot amidoallylation followed by a ring-closing metathesis step. This approach was used to complete the racemic synthesis of aza-goniothalamin 1, and is currently being expanded to generate new biologically relevant derivatives.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental, characterization data and copies of spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.2 MB | Download |

References

-

Zhang, B.; Studer, A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3505–3521. doi:10.1039/c5cs00083a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vo, C.-V. T.; Bode, J. W. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2809–2815. doi:10.1021/jo5001252

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mori, M. Heterocycles 2009, 78, 281–318. doi:10.3987/rev-08-641

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Royer, J., Ed. Asymmetric Synthesis of Nitrogen Heterocycles; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; 10.1002/9783527625505. doi:10.1002/9783527625505

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, N.; Shu, Y.-J.; Wang, B.-Z.; Li, X.-Z.; Bi, F.-Q. Curr. Org. Chem. 2015, 19, 1896–1915. doi:10.2174/1385272819666150622174626

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Samanta, S.; Sinha, B. Synthesis 2012, 817–847. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1289734

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stark, D. G.; Morrill, L. C.; Yeh, P.-P.; Slawin, A. M. Z.; O'Riordan, T. J. C.; Smith, A. D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11642–11646. doi:10.1002/anie.201306786

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, L.-L.; Li, X.-S.; Cao, L.-L.; Zhang, R.; Shi, X.-Q.; Qi, J. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 5985–5988. doi:10.1039/c7cc02753b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, Y.; Hardman, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 8576–8593. doi:10.1039/c7ob01948c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gao, Z.-H.; Chen, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.-M.; Ye, S. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12040–12043. doi:10.1039/c5cc04593b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wanner, B.; Mahatthananchai, J.; Bode, J. W. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5378–5381. doi:10.1021/ol202272t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barrow, J. C.; Nanterment, P. G.; Selnick, H. G. Dihydropyridinones and pyrrolinones useful as alpha 1A adrenoceptor antagonists. U.S. Patent US6235759B1, May 22, 2001.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Turdi, H.; Hangeland, J. J.; Lawrence, R. M.; Cheng, D.; Ahmad, S.; Meng, W.; Brigance, P. R.; Devasthale, P.; Zhao, G. Aryl dihydropyridinones and piperidinone as MGAT2 inhibitors. Eur. Pat. Appl. EP2785693A1, Oct 8, 2014.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hlubucek, J. R.; Robertson, A. V. Aust. J. Chem. 1967, 20, 2199–2206. doi:10.1071/ch9672199

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Barcelos, R. C.; Pastre, J. C.; Caixeta, V.; Vendramini-Costa, D. B.; de Carvalho, J. E.; Pilli, R. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 3635–3651. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2012.03.059

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Innajak, S.; Mahabusrakum, W.; Watanapokasin, R. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 2851–2858. doi:10.3892/or.2016.4655

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Barcelos, R. C.; Pastre, J. C.; Vendramini-Costa, D. B.; Caixeta, V.; Longato, G. B.; Monteiro, P. A.; de Carvalho, J. E.; Pilli, R. A. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 2725–2743. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201402292

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Barcelos, R. C.; Pelizzaro-Rocha, K. J.; Pastre, J. C.; Dias, M. P.; Ferreira-Halder, C. V.; Pilli, R. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 87, 745–758. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.09.085

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Veenstra, S. J.; Schmid, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 997–1000. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(96)02458-6

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Vanier, C.; Wagner, A.; Mioskowski, C. Chem. – Eur. J. 2001, 7, 2318–2323. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20010601)7:11<2318::aid-chem23180>3.0.co;2-w

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Fiorelli, C.; Savoia, D. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6022–6028. doi:10.1021/jo0703000

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Lucchetti, N.; Lancianesi, S.; Petrini, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 5433–5441. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402116

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Cogswell, T. J.; Donald, C. S.; Long, D.-L.; Marquez, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 717–728. doi:10.1039/c4ob01547a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Weilbeer, C.; Sickert, M.; Naumov, S.; Schneider, C. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 513–518. doi:10.1002/chem.201604356

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sato, M.; Azuma, H.; Daigaku, A.; Sato, S.; Takasu, K.; Okano, K.; Tokuyama, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1087–1091. doi:10.1002/anie.201609941

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Donohoe, T. J.; Bower, J. F.; Basutto, J. A.; Fishlock, L. P.; Procopiou, P. A.; Callens, C. K. A. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 8969–8980. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.07.076

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gong, Y.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Shi, Y.-B.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, J. Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 3989–3995. doi:10.1039/c9qo01049a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, P. H.; Seomoon, D.; Kim, S.; Nagaiah, K.; Damle, S. V.; Lee, K. Synthesis 2003, 2189–2193. doi:10.1055/s-2003-41017

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Zhang, B.; Studer, A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3505–3521. doi:10.1039/c5cs00083a |

| 2. | Vo, C.-V. T.; Bode, J. W. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2809–2815. doi:10.1021/jo5001252 |

| 3. | Mori, M. Heterocycles 2009, 78, 281–318. doi:10.3987/rev-08-641 |

| 4. | Royer, J., Ed. Asymmetric Synthesis of Nitrogen Heterocycles; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; 10.1002/9783527625505. doi:10.1002/9783527625505 |

| 5. | Liu, N.; Shu, Y.-J.; Wang, B.-Z.; Li, X.-Z.; Bi, F.-Q. Curr. Org. Chem. 2015, 19, 1896–1915. doi:10.2174/1385272819666150622174626 |

| 6. | Majumdar, K. C.; Samanta, S.; Sinha, B. Synthesis 2012, 817–847. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1289734 |

| 17. | Barcelos, R. C.; Pastre, J. C.; Vendramini-Costa, D. B.; Caixeta, V.; Longato, G. B.; Monteiro, P. A.; de Carvalho, J. E.; Pilli, R. A. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 2725–2743. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201402292 |

| 18. | Barcelos, R. C.; Pelizzaro-Rocha, K. J.; Pastre, J. C.; Dias, M. P.; Ferreira-Halder, C. V.; Pilli, R. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 87, 745–758. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.09.085 |

| 15. | Barcelos, R. C.; Pastre, J. C.; Caixeta, V.; Vendramini-Costa, D. B.; de Carvalho, J. E.; Pilli, R. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 3635–3651. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2012.03.059 |

| 16. | Innajak, S.; Mahabusrakum, W.; Watanapokasin, R. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 2851–2858. doi:10.3892/or.2016.4655 |

| 14. | Hlubucek, J. R.; Robertson, A. V. Aust. J. Chem. 1967, 20, 2199–2206. doi:10.1071/ch9672199 |

| 15. | Barcelos, R. C.; Pastre, J. C.; Caixeta, V.; Vendramini-Costa, D. B.; de Carvalho, J. E.; Pilli, R. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 3635–3651. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2012.03.059 |

| 16. | Innajak, S.; Mahabusrakum, W.; Watanapokasin, R. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 2851–2858. doi:10.3892/or.2016.4655 |

| 20. | Vanier, C.; Wagner, A.; Mioskowski, C. Chem. – Eur. J. 2001, 7, 2318–2323. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20010601)7:11<2318::aid-chem23180>3.0.co;2-w |

| 21. | Fiorelli, C.; Savoia, D. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6022–6028. doi:10.1021/jo0703000 |

| 22. | Lucchetti, N.; Lancianesi, S.; Petrini, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 5433–5441. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402116 |

| 23. | Cogswell, T. J.; Donald, C. S.; Long, D.-L.; Marquez, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 717–728. doi:10.1039/c4ob01547a |

| 7. | Stark, D. G.; Morrill, L. C.; Yeh, P.-P.; Slawin, A. M. Z.; O'Riordan, T. J. C.; Smith, A. D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11642–11646. doi:10.1002/anie.201306786 |

| 8. | Zhao, L.-L.; Li, X.-S.; Cao, L.-L.; Zhang, R.; Shi, X.-Q.; Qi, J. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 5985–5988. doi:10.1039/c7cc02753b |

| 9. | Yang, Y.; Hardman, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 8576–8593. doi:10.1039/c7ob01948c |

| 10. | Gao, Z.-H.; Chen, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.-M.; Ye, S. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12040–12043. doi:10.1039/c5cc04593b |

| 11. | Wanner, B.; Mahatthananchai, J.; Bode, J. W. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5378–5381. doi:10.1021/ol202272t |

| 12. | Barrow, J. C.; Nanterment, P. G.; Selnick, H. G. Dihydropyridinones and pyrrolinones useful as alpha 1A adrenoceptor antagonists. U.S. Patent US6235759B1, May 22, 2001. |

| 13. | Turdi, H.; Hangeland, J. J.; Lawrence, R. M.; Cheng, D.; Ahmad, S.; Meng, W.; Brigance, P. R.; Devasthale, P.; Zhao, G. Aryl dihydropyridinones and piperidinone as MGAT2 inhibitors. Eur. Pat. Appl. EP2785693A1, Oct 8, 2014. |

| 27. | Gong, Y.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Shi, Y.-B.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, J. Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 3989–3995. doi:10.1039/c9qo01049a |

| 28. | Lee, P. H.; Seomoon, D.; Kim, S.; Nagaiah, K.; Damle, S. V.; Lee, K. Synthesis 2003, 2189–2193. doi:10.1055/s-2003-41017 |

| 20. | Vanier, C.; Wagner, A.; Mioskowski, C. Chem. – Eur. J. 2001, 7, 2318–2323. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20010601)7:11<2318::aid-chem23180>3.0.co;2-w |

| 21. | Fiorelli, C.; Savoia, D. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6022–6028. doi:10.1021/jo0703000 |

| 22. | Lucchetti, N.; Lancianesi, S.; Petrini, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 5433–5441. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402116 |

| 23. | Cogswell, T. J.; Donald, C. S.; Long, D.-L.; Marquez, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 717–728. doi:10.1039/c4ob01547a |

| 19. | Veenstra, S. J.; Schmid, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 997–1000. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(96)02458-6 |

| 19. | Veenstra, S. J.; Schmid, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 997–1000. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(96)02458-6 |

| 20. | Vanier, C.; Wagner, A.; Mioskowski, C. Chem. – Eur. J. 2001, 7, 2318–2323. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20010601)7:11<2318::aid-chem23180>3.0.co;2-w |

| 21. | Fiorelli, C.; Savoia, D. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6022–6028. doi:10.1021/jo0703000 |

| 22. | Lucchetti, N.; Lancianesi, S.; Petrini, M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 5433–5441. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402116 |

| 23. | Cogswell, T. J.; Donald, C. S.; Long, D.-L.; Marquez, R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 717–728. doi:10.1039/c4ob01547a |

| 26. | Donohoe, T. J.; Bower, J. F.; Basutto, J. A.; Fishlock, L. P.; Procopiou, P. A.; Callens, C. K. A. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 8969–8980. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.07.076 |

| 19. | Veenstra, S. J.; Schmid, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 997–1000. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(96)02458-6 |

| 14. | Hlubucek, J. R.; Robertson, A. V. Aust. J. Chem. 1967, 20, 2199–2206. doi:10.1071/ch9672199 |

| 15. | Barcelos, R. C.; Pastre, J. C.; Caixeta, V.; Vendramini-Costa, D. B.; de Carvalho, J. E.; Pilli, R. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 3635–3651. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2012.03.059 |

| 16. | Innajak, S.; Mahabusrakum, W.; Watanapokasin, R. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 2851–2858. doi:10.3892/or.2016.4655 |

| 17. | Barcelos, R. C.; Pastre, J. C.; Vendramini-Costa, D. B.; Caixeta, V.; Longato, G. B.; Monteiro, P. A.; de Carvalho, J. E.; Pilli, R. A. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 2725–2743. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201402292 |

| 18. | Barcelos, R. C.; Pelizzaro-Rocha, K. J.; Pastre, J. C.; Dias, M. P.; Ferreira-Halder, C. V.; Pilli, R. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 87, 745–758. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.09.085 |

| 24. | Weilbeer, C.; Sickert, M.; Naumov, S.; Schneider, C. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 513–518. doi:10.1002/chem.201604356 |

| 25. | Sato, M.; Azuma, H.; Daigaku, A.; Sato, S.; Takasu, K.; Okano, K.; Tokuyama, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1087–1091. doi:10.1002/anie.201609941 |

© 2020 Cogswell et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)