Abstract

Dilithio sulfonyl methandiides are a synthetically and structurally highly interesting group of functionalized geminal dianions. Although very desirable, knowledge of the structure of dilithio methandiides in solution was lacking up to now. Herein, we describe the isolation and determination of the structure of tetrameric dilithio (trimethylsilyl)(phenylsulfonyl) methandiide in solution and in the crystal. The elucidation of the structure of the tetramer is based on crystal structure analysis and 13C/6Li NMR spectroscopic data. A characteristic feature of the structure of the tetramer is the C2 symmetric C–Li chain, composed of four doubly Li-coordinated dianionic carbon and five Li atoms. Three Li atoms are devoid of a contact to a dianionic C atom. The tetramer, the dianionic C atoms of which undergo fast exchange, is in THF solution in fast equilibrium with a further aggregate, which is stable only at low temperatures.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Functionalized dilithio methandiides I–III (Figure 1) are a fascinating class of compounds, whose reactivity, synthetic potential, and structure have received much interest in organic and metalorganic chemistry [1,2]. The most interesting aspects of compounds I–III are the likelihood of the formation of two new carbon–carbon and carbon–metal bonds, and the bonding situation of the dianionic carbon atom, including its electronic structure and coordination geometry, together with the possibility of a coordination by two lithium atoms.

Figure 1: Functionalized dilithio methandiides (FG = functional group).

Figure 1: Functionalized dilithio methandiides (FG = functional group).

The sulfonyl dilithio methandiides 2, carrying various substituents R1 and R2, have attracted particular attention [1-6]. Reactivity studies of 2 with carbon and metal-based electrophiles revealed a high synthetic potential, allowing, for example, the synthesis of carbo- and heterocycles [4,6], and transition-metal carbene complexes [1,2], carrying the synthetically versatile sulfonyl group [7,8].

Dilithio methandiides 2 are accessible from sulfonyl lithio methanides 1 [9] through α-deprotonation [1,2,4], and from arylsulfonyl dilithio methanides 3 [10,11] though ortho,α-transmetallation [10-13] (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Synthesis of sulfonyl dilithio methandiides 2.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of sulfonyl dilithio methandiides 2.

We had found that the α-deprotonation of the lithio methanide 1a with n-butyllithium (n-BuLi) gave the stable silyl and sulfonyl-substituted dilithio methandiide 2a [14,15]. The use of n-BuLi, inadvertently containing Li2O, had yielded prismatic crystals of 2a. An X-ray crystal structure analysis had shown a Ci symmetric hexamer, (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6, the dianionic C atoms of which are each coordinated by two Li atoms in a non-planar fashion (vide infra) [15]. Because of the general interest in dilithio methandiides that remains unabated to this day, crystal structure analysis has been carried out of a large number of derivatives [16-43]. They generally showed intricate aggregates with complex C–Li and C–Li–heteroatom chains, containing doubly lithiated C atoms. However, as much as there is now knowledge of the structure of dilithio methandiides in the crystal, as little is known about the structure and dynamics in solution [1,2,16-43]. The main obstacles at characterizing dilithio methandiides in terms of aggregate size, C–Li connectivity, Li coordination of the dianionic C atoms, and dynamics were poor solubility and problems to locate the 13C signals of the dianionic C atoms or the detection of only broad ones. Knowledge of the solution structure of dilithio methandiides would be, however, highly desirable in order to obtain a more complete understanding of the reactivity and coordination chemistry in general, and of the dianionic C atom in particular. During the structural investigation of 2a it was observed that the Li2O-free methandiide is in contrast to (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 readily soluble in THF. 6Li and 13C NMR spectroscopy of 2a had led to the detection of an aggregate, a substructure of which could be disclosed [15].

We describe in this paper the isolation of a tetramer of 2a and the determination of its structure in solution based on crystal structure analysis and previously described NMR spectroscopic data.

Results and Discussion

Crystal structure

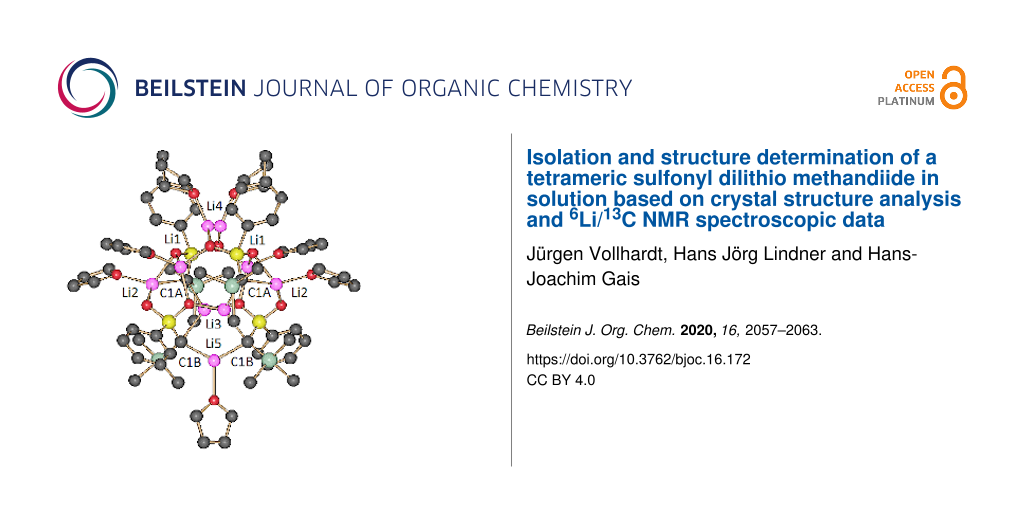

Treatment of sulfone 4 in a mixture of THF and n-hexane with Li2O-free n-BuLi (1.88 equiv) in n-hexane at −90 °C followed by warming the solution to room temperature gave octahedral crystals of 2a. The use of two equivalents of the base led two a slower crystal growth. The X-ray crystal structure analysis showed a chiral C2 symmetric tetramer, (2a)4·(THF)6, containing six THF molecules (Figure 2) [44]. The lithium atom Li4 is not exactly located on the C2 axis. It is resolved by two Li4 in general positions near the C2 axis each with an occupancy of 0.5. Therefore, Figure 2 shows two positions for Li4 and the attached THF molecule (see the Supporting Information File 1 for details). The aggregate has two different types of dianionic carbon atoms, C1A and C1B, which are each coordinated by two Li atoms. Five Li atoms are coordinated by carbon atoms (2 Li2, 2 Li3 and Li5) and three Li atoms are without contact to a carbon atom and only coordinated by oxygen atoms (2 Li1 and Li4). Lithium atoms Li3 and Li5, which are each coordinated by two dianionic carbon atoms, have planar trigonal coordination geometry. The coordination geometry of C1A and C1B is characterized by τ4 values [45] of 0.68 and 0.86, respectively, indicating seesaw geometry for C1A and a trigonal pyramidal one for C1B.

![[1860-5397-16-172-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-172-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Structure of (2a)4·(THF)6 in the crystal. Color code: black, C; green, Si; yellow, S; red, O; pink, Li. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Lithium atoms Li1 are unmarked because of a lack of space.

Figure 2: Structure of (2a)4·(THF)6 in the crystal. Color code: black, C; green, Si; yellow, S; red, O; pink,...

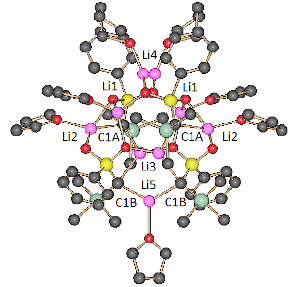

The most interesting structural feature of tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 is the linear carbon–lithium chain shown in Figure 3, which has C2 symmetry and contains the four dianionic carbon atoms and five lithium atoms. It will be shown later that the presence of this chain is the key to the assignment of the structure of the aggregate in solution (vide infra).

![[1860-5397-16-172-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-172-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: The C2 symmetric carbon–lithium chain of aggregate (2a)4·(THF)6 in the crystal (color code: black, C; pink, Li). All atoms except C1A, C1B, Li2, Li3, and Li5 are omitted for clarity.

Figure 3: The C2 symmetric carbon–lithium chain of aggregate (2a)4·(THF)6 in the crystal (color code: black, ...

The tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 shows besides the C–Li chain a number of further interesting structural features. Lithium atom Li5 bridges an eight-membered (C–Li–O–S)2 ring at the carbon atoms, while Li4 overpasses an eight-membered (O–S–O–Li)2 ring at the oxygen atoms. Eight-membered (O–S–O–Li)2 rings of this type are also found as typical structural element of dimeric sulfonyl lithio methanides 1 in the crystal [46-50]. The atoms C1A, Li2, O1A, and S1 are embedded in two four-membered rings, while two lithium atoms, a sulfur atom, and three oxygen atoms form two six-membered rings. Because of the presence of C–Li and O–Li bonds in (2a)4·(THF)6, the dicarbanions are both C,C- and O,Li-dilithiated species.

The C–Li, C–S, and O–Li bond lengths (Table 1) of the tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 are in the range of those found in the hexamer (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 and functionalized dilithio sulfonyl methandiides [40,43].

Table 1: Selected bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles of (2a)4·(THF)6.

| bond lengthsa | bond anglesb |

| C1A–S 156.8(6) | C1A-S-C2A 115.4(3) |

| C1B–S 158.7(6) | C1A–Li3–C1B 120.9(5) |

| C1A–Li2 222.2(11) | O1F–Li5–C1B 118.6(4) |

| C1A–Li3 222.7(11) | C1B–Li5–C1B 122.8(7) |

| C1B–Li3 224.2(11) | O2B–Li3–C1A 117.2(5) |

| C1B–Li5 209.8(9) | O2B–Li3–C1B 121.4(5) |

| O1–Li2 216.7(12) | S-C1A-Si 125.4(4) |

| O1–Li1 196.7(10) | C1B-S-C2B 115.3(3) |

| O2–Li4 187(4) | Li2–C1A–Li3 86.2(4) |

| O1B–Li2 189.1(11) | S-C1A-Li2 85.2(4) |

| O2B–Li1 195.6(10) | Li5–C1B–Li3 91.4(4) |

| C1A–Si 179.3(6) | S-C1B-Si 117.9(3) |

| C1B–Si 180.9(6) | |

| dihedral anglesb | |

| Li2–C1A–Li3–C1B 35.2(6) | C2A-S-C1A-Si 51.2(5) |

| Li3–C1B–Li5–C1B 33.6(3) | C2B-S-C1B-Si 78.6(4) |

aIn pm. bIn degree.

Solution structure

The synthesis of 2a from sulfone 6Li and 13C-labelled 4 with Li2O-free n-BuLi had yielded the methandiide, being readily soluble in THF. 13C and 6Li NMR spectroscopy of 13C,6Li-2a in [D8]THF [15,51-53] had shown an aggregate, 2a-I, which is present in the whole temperature range from 22 °C to −103 °C. The formation of a further equilibrium aggregate, 2a-II, was detected from −50 °C downwards. The equilibrium between the aggregates lies at −103 °C on the side of 2a-II. Interestingly, formation of 2a-II in THF could not be detected when diglyme was present.

According to the 13C and 6Li NMR spectroscopic experiments of 2a-I at −103 °C, the aggregate contains a C2 symmetric linear carbon–lithium chain composed of the four dianionic carbon and five lithium atoms (Figure 4).

Figure 4: C2 Symmetric carbon–lithium chain of 2a-I in THF, showing the carbon–lithium connectivities, multiplicities of the NMR signals (left), and magnitudes of 1J(6Li,13C) couplings in Hz (right) [15].

Figure 4: C2 Symmetric carbon–lithium chain of 2a-I in THF, showing the carbon–lithium connectivities, multip...

The carbon–lithium chain includes three different types of lithium atoms, Li2, Li3, and Li5 and two different types of dianionic atoms, C1A and C1B. The 13C NMR spectrum of 13C,6Li-2a-I at −103 °C showed a quintet (q) for C1A (δ = 49.9 ppm) and a multiplet (m) for C1B (δ = 51.4 ppm) due to 6Li,13C spin coupling. The 6Li NMR spectrum of 2a-I at −103 °C displayed three signals split by 6Li,13C spin coupling. Selective 6Li{13C} double resonance and two-dimensional double quantum based shift correlation experiments had served to establish the 6Li–13C connectivity. In addition, 6Li spin echo spectroscopy with gated 13C decoupling had confirmed the multiplicities of the 6Li signals. All together these experiments had established a triplet (t) structure for the signals of Li3 (δ = 2.62 pm) and Li5 (δ = 2.86 pm) and a doublet (d) structure for the signal of Li2 (δ = 1.17 pm) [15,51-53]. Essential for the success of the NMR spectroscopic investigation of 2a was the 13C,6Li labelling of the dilithio methandiide. It allowed the detection of the otherwise low intensity signals of the dianionic carbon atoms of the aggregates and the attainment of signals with a small line width [54].

The complete connectivity of the carbon–lithium chain of 2a-II could not be revealed, since the determination of the multiplicities of all 6Li and 13C signals failed.

Undoubtedly, the C2 symmetric linear C–Li chain is the most revealing structural feature of tetramer 2a-I, since it contains besides Li atoms the four dianionic C atoms. A chain having these carbon–lithium connectivities is contained in tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 in the crystal. The excellent agreement between the two C–Li chains shows that 2a-I is a tetramer, adopting in solution the same structure as the tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 in the crystal. Although the lithium oxygen bonds of 2a-I evaded a direct detection by NMR spectroscopy, the 13C,6Li shift correlation experiments of 2a-I had shown two 6Li signals, lacking correlation with 13C signals [15]. Thus, there is good reason to believe that the lithium oxygen bonds of (2a)4·(THF)6 are retained in 2a-I in solution. Most likely, six lithium atoms of 2a-I are coordinated by THF molecules in a similar way as in tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6.

The aggregate 2a-I is fluxional in THF with an estimated barrier of ΔG≠ = 12.0 ± 0.5 kcal/mol (248 K) for the exchange of the dianionic C atoms C1A and C1B [53]. An intra-aggregate exchange seems to be less probable, because it would require an extensive carbon lithium and oxygen lithium bond reorganization (cf. Figure 2). A more likely scenario for the exchange would be the existence of a THF-assisted tetramer–dimer equilibrium.

Bonding of the dianionic C atoms

6Li NMR spectroscopy of tetramer 2a-I had revealed a dianionic carbon atom, C1B, carrying two different Li atoms, a bonding situation which is reflected by the two different 6Li,13C coupling constants. It was thus of particular interest to see whether this feature is mirrored by the bonding situation of C1B of (2a)4·(THF)6. An inspection of the tetramer shows for C1B different carbon–lithium bond lengths, while those of C1A are similar in length. The shorter C1B–Li5 bond corresponds to a larger and the longer C1B–Li3 bond to a smaller 6Li,13C coupling constant (Table 2). Accordingly, the similar coupling constants of C1A in 2a-I are matched by similar carbon lithium bond lengths of C1A in (2a)4·(THF)6. It is generally accepted that the carbon lithium interaction in dilithio methandiides is ionic in nature [1,2]. The observation of 6Li,13C couplings shows, however, that the carbon lithium bonds in 2a-I have a covalent contribution as generally observed for organolithiums [55].

Table 2: 1J(13C,6Li) coupling constants of 2a-I and bond lengths of (2a)4·(THF)6.

| bond | 2a-I | (2a)4·(THF)6 |

| 1Ja | lengthsb | |

| C1B–Li5 | 9.2 | 209.8(11) |

| C1B–Li3 | 4.9 | 224.2(11) |

| C1A–Li3 | 5.2 | 222.7(11) |

| C1A–Li2 | 5.6 | 222.2(11) |

aIn Hz. bIn pm.

Three mechanisms most likely contribute to the stabilization of the negative charge of the carbon atoms of tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 and hexamer (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6, electrostatic interaction with and charge polarization by the positively charged sulfur atom [56] and silicon atom [57], and negative nC–σ*SPh hyperconjugation [56,58]. The anions of (2a)4·(THF)6 and (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 adopt conformations around the carbon sulfur bond, which would allow for stabilization by negative hyperconjugation. Density functional theory and natural bond order calculations of dilithio methandiides of type II [32,43] suggest that the two lone pairs at the dianionic carbon atom of (2a)4·(THF)6 and (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 are perhaps located in an sp2 hybridized orbital and p orbital. However, the importance and quantification of the three stabilizing factors as well as the electronic structure of 2a have to await investigation by quantum chemical calculation. It seems appropriate in this context to have a look at the bonding situation of the corresponding sulfonyl lithio methanides 1. Their anion is stabilized by electrostatic interaction, polarization, and negative nC-σ*SR hyperconjugation, with electrostatic interaction as dominating mechanism [56,58]. The lithio methanides 1 are monomeric or dimeric in THF solution and the solid state, depending on Lewis basic ligands of the lithium atom [46-50]. A characteristic feature of 1 is the formation of O–Li bonds in solution and in the crystal. The NMR spectroscopic investigation of 1, including 1a [53], gave no indication for the existence of a species with a C–Li bond. However, the failure to detect a 6Li,13C coupling is no proof for the not existence of a C–Li-bonded species, because of the possibility of a fast C,Li exchange process, even at low temperatures. While the anion of 1 carries one lone pair at the carbon atom, the anion 2 bears two lone pairs. The higher negative charge density of the carbon atom of 2 seems to be a decisive factor for the formation of C–Li bonds in the crystal and in solution.

Comparison of tetramer and hexamer

It seems interesting to compare the carbon lithium connectivity and lithium coordination of the dianionic carbon atoms of tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 and Li2O-containing hexamer (2a)6.Li2O·(THF)6. The hexamer has an octahedral cluster of lithium atoms with an oxygen atom in the center of symmetry and three different types of strongly distorted tetrahedral dianionic carbon atoms (C1A: τ4 = 0.66, C1B: τ4 = 0.75, C1C: τ4 = 0.61) (Figure 5). It contains two linear Li1–C1A–Li2–C1B–Li3 chains and two dianionic carbon atoms, C1C, outside of the chains, which are each coordinated by three Li atoms. In hexamer (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 all lithium atoms are coordinated by dianionic carbon atoms, while three lithium atoms of tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 are without contact to the dianionic C atoms. Interestingly, the structure of (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 is in contrast to that of (2a)4·(THF)6 characterized by a large number of four-membered Li–C–S–O and Li–O–Li–O chelate rings. The dianions of hexamer (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 are as those of the tetramer both C,C- and O,Li-dilithiated species.

![[1860-5397-16-172-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-172-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: the structure of (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 in the crystal [15]. Color code: black, C; green, Si; yellow, S; red, O; pink, Li. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (pm) and dihedral angles (°): C1A–Li1 218, C1A–Li2 225, C1B–Li2 219, C1B–Li3 234, C1C–Li7 223, C1C–Li4 251, C1C–Li6 283, C2A–S–C1A–Si 50, C2B–S–C1B–Si 12, C2C–S–C1C–Si 58.

Figure 5: the structure of (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 in the crystal [15]. Color code: black, C; green, Si; yellow, S; red...

Comparison of (2a)4·(THF)6 and (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 with functionalized sulfonyl dilithio methandiides

Besides the crystal structures of (2a)4·(THF)6 and (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 those of the sulfonyl dilithio methandiides IIIa (FG1 = SO2Ph, FG2 = P(S)Ph2) [36] and IIIb ((FG1 = SO2Ph, FG2 = P(NSiMe3)Ph2) [43] have been determined. Methandiides IIIa and carbanion IIIb have in contrast to 2a a further lithium atom coordinating and stabilizing heteroatom-substituent. Both methandiides are tetramers, featuring dilithiated dianionic carbon atoms with a coordination geometry, which strongly deviates from tetrahedral and O–Li, S–Li, and N–Li bonds. They are, however, devoid of C–Li chains of the type found in (2a)4·(THF)6 and (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6. The bonding situation of tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 and hexamer (2a)6·Li2O·(THF)6 indicates that the dominating structure building factor is the interaction between the charged carbon, oxygen and lithium atoms and not between orbitals. A similar conclusion was reached in the case of the dilithio methandiides IIIa and IIIb.

Conclusion

The determination of the structure of tetramer 2a-I in both the solution and solid state, which is the first of a dilithio methandiide, was achieved based on X-ray crystal structure analysis and 6Li,13C NMR spectroscopic data. The tetramer 2a-I in THF solution has the same structure as the tetramer (2a)4·(THF)6 in the crystal. A characteristic feature of the structure of the tetramer is the C2 symmetric linear C–Li chain, composed of the four dianionic C atoms and five Li atoms. Each dianionic C atom is coordinated by two Li atoms. While one dianionic C atom has seesaw coordination geometry, the other dianionic C atom has a trigonal bipyramidal one. As a consequence of the C–Li chain three Li atoms are without a contact to a dianionic C atom. The tetramer is fluxional leading to an exchange of the dianionic C atoms. It stands in THF in equilibrium with a second aggregate, which is only stable at low temperatures.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental details, crystal data, and parameters of data collection for tetramer (2a)4.(THF)6. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 362.4 KB | Download |

References

-

Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Mézailles, N. Stable Geminal Dianions as Precursors for Gem-Diorganometallic and Carbene Complexes. In Organo-di-Metallic Compounds (or Reagents); Xi, Z., Ed.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 47; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp 63–128. doi:10.1007/3418_2014_74

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Nebra, N.; Mézailles, N. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8555–8700. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00802

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Thomson, C. M. Dianion Chemistry in Organic Synthesis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marek, I.; Normant, J.-F. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 3241–3268. doi:10.1021/cr9600161

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Langer, P.; Freiberg, W. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4125–4150. doi:10.1021/cr010203l

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Foubelo, F.; Yus, M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005, 9, 459–490. doi:10.2174/1385272053174921

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

El-Awa, A.; Noshi, M. N.; du Jourdin, X. M.; Fuchs, P. L. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2315–2349. doi:10.1021/cr800309r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Trost, B. M.; Kalnmals, C. A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 11193–11213. doi:10.1002/chem.201902019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ruano, J. L. G.; Parra, A.; Alemán, J. Sulfur-bearing lithium compounds in modern synthesis. In Lithium Compounds in Organic Synthesis; Luisi, R.; Capriati, V., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2014; pp 225–270. doi:10.1002/9783527667512.ch8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vollhardt, J.; Gais, H.-J.; Lukas, K. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1985, 24, 610–611. doi:10.1002/anie.198506101

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 1529–1532. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)80343-3

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wessels, M.; Mahajan, V.; Boßhammer, S.; Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2431–2449. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201100066

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Řehová, L.; Jahn, U. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 4610–4623. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402171

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vollhardt, J.; Gais, H.-J.; Lukas, K. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1985, 24, 696–697. doi:10.1002/anie.198506961

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] -

Pilz, M.; Allwohn, J.; Hunold, R.; Massa, W.; Berndt, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1988, 27, 1370–1372. doi:10.1002/anie.198813701

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zarges, W.; Marsch, M.; Harms, K.; Boche, G. Chem. Ber. 1989, 122, 1307–1311. doi:10.1002/cber.19891220714

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Zehnder, M. Helv. Chim. Acta 1997, 80, 2182–2190. doi:10.1002/hlca.19970800717

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Spingler, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 92–94. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990115)38:1/2<92::aid-anie92>3.0.co;2-u

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Spingler, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 3549–3552. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991203)38:23<3549::aid-anie3549>3.0.co;2-d

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ong, C. M.; Stephan, D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 2939–2940. doi:10.1021/ja9839421

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kasani, A.; Kamalesh Babu, R. P.; McDonald, R.; Cavell, R. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1483–1484. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990517)38:10<1483::aid-anie1483>3.0.co;2-d

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Müller, J. F. K. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 789–799. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0682(200005)2000:5<789::aid-ejic789>3.0.co;2-s

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sahin, Y.; Hartmann, M.; Geiseler, G.; Schweikart, D.; Balzereit, C.; Frenking, G.; Massa, W.; Berndt, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2662–2665. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010716)40:14<2662::aid-anie2662>3.0.co;2-v

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Henderson, K. W.; Kennedy, A. R.; MacDougall, D. J.; Shanks, D. Organometallics 2002, 21, 606–616. doi:10.1021/om0107845

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Linti, G.; Rodig, A.; Pritzkow, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4503–4506. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20021202)41:23<4503::aid-anie4503>3.0.co;2-5

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cantat, T.; Mézailles, N.; Ricard, L.; Jean, Y.; Le Floch, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6382–6385. doi:10.1002/anie.200461392

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cantat, T.; Ricard, L.; Le Floch, P.; Mézailles, N. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4965–4976. doi:10.1021/om060450l

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Demange, M.; Boubekeur, L.; Auffrant, A.; Mézailles, N.; Ricard, L.; Le Goff, X.; Le Floch, P. New J. Chem. 2006, 30, 1745–1754. doi:10.1039/b610049j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hull, K. L.; Noll, B. C.; Henderson, K. W. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4072–4074. doi:10.1021/om0605635

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cantat, T.; Jacques, X.; Ricard, L.; Le Goff, X. F.; Mézailles, N.; Le Floch, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5947–5950. doi:10.1002/anie.200701588

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hull, K. L.; Carmichael, I.; Noll, B. C.; Henderson, K. W. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3939–3953. doi:10.1002/chem.200701976

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Chen, J.-H.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; So, C.-W. Organometallics 2009, 28, 4617–4620. doi:10.1021/om900364j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cooper, O. J.; McMaster, J.; Lewis, W.; Blake, A. J.; Liddle, S. T. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 5074–5076. doi:10.1039/c0dt00152j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cooper, O. J.; Wooles, A. J.; McMaster, J.; Lewis, W.; Blake, A. J.; Liddle, S. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5570–5573. doi:10.1002/anie.201002483

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Schröter, P.; Gessner, V. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 11223–11227. doi:10.1002/chem.201201369

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Heuclin, H.; Le Goff, X. F.; Mézailles, N. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 16136–16144. doi:10.1002/chem.201202680

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Heuclin, H.; Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Ho, S. Y.-F.; Le Goff, X.-F.; Carenco, S.; So, C.-W.; Mézailles, N. Organometallics 2013, 32, 498–508. doi:10.1021/om300954a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gessner, V. H.; Meier, F.; Uhrich, D.; Kaupp, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 16729–16739. doi:10.1002/chem.201303115

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14399–14408. doi:10.1039/c4dt01466a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Sindlinger, C. P.; Stasch, A. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14334–14345. doi:10.1039/c4dt01185f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Feichtner, K.-S.; Englert, S.; Gessner, V. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 506–510. doi:10.1002/chem.201504724

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Inorganics 2016, 4, 40. doi:10.3390/inorganics4040040

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

CCDC 1992567 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, L.; Powell, D. R.; Houser, R. P. Dalton Trans. 2007, 955–964. doi:10.1039/b617136b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boche, G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1989, 28, 277–297. doi:10.1002/anie.198902771

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Linnert, M.; Bruhn, C.; Wagner, C.; Steinborn, D. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 691, 2358–2367. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.12.048

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Scholz, R.; Hellmann, G.; Rohs, S.; Raabe, G.; Runsink, J.; Özdemir, D.; Luche, O.; Heß, T.; Giesen, A. W.; Atodiresei, J.; Lindner, H. J.; Gais, H.-J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 4559–4587. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201000409

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hellmann, G.; Hack, A.; Thiemermann, E.; Luche, O.; Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 3869–3897. doi:10.1002/chem.201204014

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gerhards, F.; Griebel, N.; Runsink, J.; Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 17904–17920. doi:10.1002/chem.201503123

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Bast, P.; Schmalz, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1987, 26, 1212–1220. doi:10.1002/anie.198712121

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Moskau, D. Two-dimensional NMR correlation spectroscopy of quadrupolar nuclei. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany, 1987.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Vollhardt, J. Alkalimetal and titanium derivatives of sulfones: synthesis, structure and reactivity. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 1990.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Günther, H. High-resolution 6,7Li NMR of Organolithium Compounds. In Advanced Applications of NMR to Organometallic Chemistry; Gielen, M.; Willem, R.; Wrackmeyer, B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, U.K., 1996.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Streitwieser, A.; Bacharach, S. M.; Dorigo, A.; Schleyer, P. v. R. Bonding, Structure and Energetics in Organolithium Compounds. In Lithium Chemistry: A theoretical and experimental overview; Saps, A.-M.; Schleyer, P. v. R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp 1–43.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Glendening, E. D.; Shrout, A. L. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 4966–4972. doi:10.1021/jp058010f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Ott, H.; Däschlein, C.; Leusser, D.; Schildbach, D.; Seibel, T.; Stalke, D.; Strohmann, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11901–11911. doi:10.1021/ja711104q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J.; Fleischhauer, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4622–4630. doi:10.1021/ja953034t

Return to citation in text: [1] [2]

| 57. | Ott, H.; Däschlein, C.; Leusser, D.; Schildbach, D.; Seibel, T.; Stalke, D.; Strohmann, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11901–11911. doi:10.1021/ja711104q |

| 56. | Glendening, E. D.; Shrout, A. L. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 4966–4972. doi:10.1021/jp058010f |

| 58. | Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J.; Fleischhauer, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4622–4630. doi:10.1021/ja953034t |

| 32. | Hull, K. L.; Carmichael, I.; Noll, B. C.; Henderson, K. W. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3939–3953. doi:10.1002/chem.200701976 |

| 43. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Inorganics 2016, 4, 40. doi:10.3390/inorganics4040040 |

| 1. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Mézailles, N. Stable Geminal Dianions as Precursors for Gem-Diorganometallic and Carbene Complexes. In Organo-di-Metallic Compounds (or Reagents); Xi, Z., Ed.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 47; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp 63–128. doi:10.1007/3418_2014_74 |

| 2. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Nebra, N.; Mézailles, N. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8555–8700. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00802 |

| 7. | El-Awa, A.; Noshi, M. N.; du Jourdin, X. M.; Fuchs, P. L. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2315–2349. doi:10.1021/cr800309r |

| 8. | Trost, B. M.; Kalnmals, C. A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 11193–11213. doi:10.1002/chem.201902019 |

| 44. | CCDC 1992567 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033. |

| 1. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Mézailles, N. Stable Geminal Dianions as Precursors for Gem-Diorganometallic and Carbene Complexes. In Organo-di-Metallic Compounds (or Reagents); Xi, Z., Ed.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 47; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp 63–128. doi:10.1007/3418_2014_74 |

| 2. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Nebra, N.; Mézailles, N. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8555–8700. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00802 |

| 45. | Yang, L.; Powell, D. R.; Houser, R. P. Dalton Trans. 2007, 955–964. doi:10.1039/b617136b |

| 4. | Marek, I.; Normant, J.-F. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 3241–3268. doi:10.1021/cr9600161 |

| 6. | Foubelo, F.; Yus, M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005, 9, 459–490. doi:10.2174/1385272053174921 |

| 1. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Mézailles, N. Stable Geminal Dianions as Precursors for Gem-Diorganometallic and Carbene Complexes. In Organo-di-Metallic Compounds (or Reagents); Xi, Z., Ed.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 47; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp 63–128. doi:10.1007/3418_2014_74 |

| 2. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Nebra, N.; Mézailles, N. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8555–8700. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00802 |

| 16. | Pilz, M.; Allwohn, J.; Hunold, R.; Massa, W.; Berndt, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1988, 27, 1370–1372. doi:10.1002/anie.198813701 |

| 17. | Zarges, W.; Marsch, M.; Harms, K.; Boche, G. Chem. Ber. 1989, 122, 1307–1311. doi:10.1002/cber.19891220714 |

| 18. | Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Zehnder, M. Helv. Chim. Acta 1997, 80, 2182–2190. doi:10.1002/hlca.19970800717 |

| 19. | Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Spingler, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 92–94. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990115)38:1/2<92::aid-anie92>3.0.co;2-u |

| 20. | Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Spingler, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 3549–3552. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991203)38:23<3549::aid-anie3549>3.0.co;2-d |

| 21. | Ong, C. M.; Stephan, D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 2939–2940. doi:10.1021/ja9839421 |

| 22. | Kasani, A.; Kamalesh Babu, R. P.; McDonald, R.; Cavell, R. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1483–1484. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990517)38:10<1483::aid-anie1483>3.0.co;2-d |

| 23. | Müller, J. F. K. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 789–799. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0682(200005)2000:5<789::aid-ejic789>3.0.co;2-s |

| 24. | Sahin, Y.; Hartmann, M.; Geiseler, G.; Schweikart, D.; Balzereit, C.; Frenking, G.; Massa, W.; Berndt, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2662–2665. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010716)40:14<2662::aid-anie2662>3.0.co;2-v |

| 25. | Henderson, K. W.; Kennedy, A. R.; MacDougall, D. J.; Shanks, D. Organometallics 2002, 21, 606–616. doi:10.1021/om0107845 |

| 26. | Linti, G.; Rodig, A.; Pritzkow, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4503–4506. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20021202)41:23<4503::aid-anie4503>3.0.co;2-5 |

| 27. | Cantat, T.; Mézailles, N.; Ricard, L.; Jean, Y.; Le Floch, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6382–6385. doi:10.1002/anie.200461392 |

| 28. | Cantat, T.; Ricard, L.; Le Floch, P.; Mézailles, N. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4965–4976. doi:10.1021/om060450l |

| 29. | Demange, M.; Boubekeur, L.; Auffrant, A.; Mézailles, N.; Ricard, L.; Le Goff, X.; Le Floch, P. New J. Chem. 2006, 30, 1745–1754. doi:10.1039/b610049j |

| 30. | Hull, K. L.; Noll, B. C.; Henderson, K. W. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4072–4074. doi:10.1021/om0605635 |

| 31. | Cantat, T.; Jacques, X.; Ricard, L.; Le Goff, X. F.; Mézailles, N.; Le Floch, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5947–5950. doi:10.1002/anie.200701588 |

| 32. | Hull, K. L.; Carmichael, I.; Noll, B. C.; Henderson, K. W. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3939–3953. doi:10.1002/chem.200701976 |

| 33. | Chen, J.-H.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; So, C.-W. Organometallics 2009, 28, 4617–4620. doi:10.1021/om900364j |

| 34. | Cooper, O. J.; McMaster, J.; Lewis, W.; Blake, A. J.; Liddle, S. T. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 5074–5076. doi:10.1039/c0dt00152j |

| 35. | Cooper, O. J.; Wooles, A. J.; McMaster, J.; Lewis, W.; Blake, A. J.; Liddle, S. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5570–5573. doi:10.1002/anie.201002483 |

| 36. | Schröter, P.; Gessner, V. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 11223–11227. doi:10.1002/chem.201201369 |

| 37. | Heuclin, H.; Le Goff, X. F.; Mézailles, N. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 16136–16144. doi:10.1002/chem.201202680 |

| 38. | Heuclin, H.; Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Ho, S. Y.-F.; Le Goff, X.-F.; Carenco, S.; So, C.-W.; Mézailles, N. Organometallics 2013, 32, 498–508. doi:10.1021/om300954a |

| 39. | Gessner, V. H.; Meier, F.; Uhrich, D.; Kaupp, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 16729–16739. doi:10.1002/chem.201303115 |

| 40. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14399–14408. doi:10.1039/c4dt01466a |

| 41. | Sindlinger, C. P.; Stasch, A. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14334–14345. doi:10.1039/c4dt01185f |

| 42. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Englert, S.; Gessner, V. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 506–510. doi:10.1002/chem.201504724 |

| 43. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Inorganics 2016, 4, 40. doi:10.3390/inorganics4040040 |

| 36. | Schröter, P.; Gessner, V. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 11223–11227. doi:10.1002/chem.201201369 |

| 1. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Mézailles, N. Stable Geminal Dianions as Precursors for Gem-Diorganometallic and Carbene Complexes. In Organo-di-Metallic Compounds (or Reagents); Xi, Z., Ed.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 47; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp 63–128. doi:10.1007/3418_2014_74 |

| 2. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Nebra, N.; Mézailles, N. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8555–8700. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00802 |

| 3. | Thomson, C. M. Dianion Chemistry in Organic Synthesis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. |

| 4. | Marek, I.; Normant, J.-F. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 3241–3268. doi:10.1021/cr9600161 |

| 5. | Langer, P.; Freiberg, W. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4125–4150. doi:10.1021/cr010203l |

| 6. | Foubelo, F.; Yus, M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005, 9, 459–490. doi:10.2174/1385272053174921 |

| 15. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054 |

| 43. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Inorganics 2016, 4, 40. doi:10.3390/inorganics4040040 |

| 10. | Vollhardt, J.; Gais, H.-J.; Lukas, K. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1985, 24, 610–611. doi:10.1002/anie.198506101 |

| 11. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 1529–1532. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)80343-3 |

| 12. | Wessels, M.; Mahajan, V.; Boßhammer, S.; Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2431–2449. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201100066 |

| 13. | Řehová, L.; Jahn, U. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 4610–4623. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402171 |

| 15. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054 |

| 53. | Vollhardt, J. Alkalimetal and titanium derivatives of sulfones: synthesis, structure and reactivity. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 1990. |

| 10. | Vollhardt, J.; Gais, H.-J.; Lukas, K. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1985, 24, 610–611. doi:10.1002/anie.198506101 |

| 11. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 1529–1532. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)80343-3 |

| 16. | Pilz, M.; Allwohn, J.; Hunold, R.; Massa, W.; Berndt, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1988, 27, 1370–1372. doi:10.1002/anie.198813701 |

| 17. | Zarges, W.; Marsch, M.; Harms, K.; Boche, G. Chem. Ber. 1989, 122, 1307–1311. doi:10.1002/cber.19891220714 |

| 18. | Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Zehnder, M. Helv. Chim. Acta 1997, 80, 2182–2190. doi:10.1002/hlca.19970800717 |

| 19. | Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Spingler, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 92–94. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990115)38:1/2<92::aid-anie92>3.0.co;2-u |

| 20. | Müller, J. F. K.; Neuburger, M.; Spingler, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 3549–3552. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991203)38:23<3549::aid-anie3549>3.0.co;2-d |

| 21. | Ong, C. M.; Stephan, D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 2939–2940. doi:10.1021/ja9839421 |

| 22. | Kasani, A.; Kamalesh Babu, R. P.; McDonald, R.; Cavell, R. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1483–1484. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990517)38:10<1483::aid-anie1483>3.0.co;2-d |

| 23. | Müller, J. F. K. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 789–799. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0682(200005)2000:5<789::aid-ejic789>3.0.co;2-s |

| 24. | Sahin, Y.; Hartmann, M.; Geiseler, G.; Schweikart, D.; Balzereit, C.; Frenking, G.; Massa, W.; Berndt, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2662–2665. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010716)40:14<2662::aid-anie2662>3.0.co;2-v |

| 25. | Henderson, K. W.; Kennedy, A. R.; MacDougall, D. J.; Shanks, D. Organometallics 2002, 21, 606–616. doi:10.1021/om0107845 |

| 26. | Linti, G.; Rodig, A.; Pritzkow, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4503–4506. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20021202)41:23<4503::aid-anie4503>3.0.co;2-5 |

| 27. | Cantat, T.; Mézailles, N.; Ricard, L.; Jean, Y.; Le Floch, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6382–6385. doi:10.1002/anie.200461392 |

| 28. | Cantat, T.; Ricard, L.; Le Floch, P.; Mézailles, N. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4965–4976. doi:10.1021/om060450l |

| 29. | Demange, M.; Boubekeur, L.; Auffrant, A.; Mézailles, N.; Ricard, L.; Le Goff, X.; Le Floch, P. New J. Chem. 2006, 30, 1745–1754. doi:10.1039/b610049j |

| 30. | Hull, K. L.; Noll, B. C.; Henderson, K. W. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4072–4074. doi:10.1021/om0605635 |

| 31. | Cantat, T.; Jacques, X.; Ricard, L.; Le Goff, X. F.; Mézailles, N.; Le Floch, P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5947–5950. doi:10.1002/anie.200701588 |

| 32. | Hull, K. L.; Carmichael, I.; Noll, B. C.; Henderson, K. W. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3939–3953. doi:10.1002/chem.200701976 |

| 33. | Chen, J.-H.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; So, C.-W. Organometallics 2009, 28, 4617–4620. doi:10.1021/om900364j |

| 34. | Cooper, O. J.; McMaster, J.; Lewis, W.; Blake, A. J.; Liddle, S. T. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 5074–5076. doi:10.1039/c0dt00152j |

| 35. | Cooper, O. J.; Wooles, A. J.; McMaster, J.; Lewis, W.; Blake, A. J.; Liddle, S. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5570–5573. doi:10.1002/anie.201002483 |

| 36. | Schröter, P.; Gessner, V. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 11223–11227. doi:10.1002/chem.201201369 |

| 37. | Heuclin, H.; Le Goff, X. F.; Mézailles, N. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 16136–16144. doi:10.1002/chem.201202680 |

| 38. | Heuclin, H.; Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Ho, S. Y.-F.; Le Goff, X.-F.; Carenco, S.; So, C.-W.; Mézailles, N. Organometallics 2013, 32, 498–508. doi:10.1021/om300954a |

| 39. | Gessner, V. H.; Meier, F.; Uhrich, D.; Kaupp, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 16729–16739. doi:10.1002/chem.201303115 |

| 40. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14399–14408. doi:10.1039/c4dt01466a |

| 41. | Sindlinger, C. P.; Stasch, A. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14334–14345. doi:10.1039/c4dt01185f |

| 42. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Englert, S.; Gessner, V. H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 506–510. doi:10.1002/chem.201504724 |

| 43. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Inorganics 2016, 4, 40. doi:10.3390/inorganics4040040 |

| 15. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054 |

| 1. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Mézailles, N. Stable Geminal Dianions as Precursors for Gem-Diorganometallic and Carbene Complexes. In Organo-di-Metallic Compounds (or Reagents); Xi, Z., Ed.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 47; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp 63–128. doi:10.1007/3418_2014_74 |

| 2. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Nebra, N.; Mézailles, N. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8555–8700. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00802 |

| 4. | Marek, I.; Normant, J.-F. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 3241–3268. doi:10.1021/cr9600161 |

| 56. | Glendening, E. D.; Shrout, A. L. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 4966–4972. doi:10.1021/jp058010f |

| 58. | Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J.; Fleischhauer, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4622–4630. doi:10.1021/ja953034t |

| 9. | Ruano, J. L. G.; Parra, A.; Alemán, J. Sulfur-bearing lithium compounds in modern synthesis. In Lithium Compounds in Organic Synthesis; Luisi, R.; Capriati, V., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2014; pp 225–270. doi:10.1002/9783527667512.ch8 |

| 14. | Vollhardt, J.; Gais, H.-J.; Lukas, K. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1985, 24, 696–697. doi:10.1002/anie.198506961 |

| 15. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054 |

| 46. | Boche, G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1989, 28, 277–297. doi:10.1002/anie.198902771 |

| 47. | Linnert, M.; Bruhn, C.; Wagner, C.; Steinborn, D. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 691, 2358–2367. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.12.048 |

| 48. | Scholz, R.; Hellmann, G.; Rohs, S.; Raabe, G.; Runsink, J.; Özdemir, D.; Luche, O.; Heß, T.; Giesen, A. W.; Atodiresei, J.; Lindner, H. J.; Gais, H.-J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 4559–4587. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201000409 |

| 49. | Hellmann, G.; Hack, A.; Thiemermann, E.; Luche, O.; Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 3869–3897. doi:10.1002/chem.201204014 |

| 50. | Gerhards, F.; Griebel, N.; Runsink, J.; Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 17904–17920. doi:10.1002/chem.201503123 |

| 15. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054 |

| 51. | Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Bast, P.; Schmalz, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1987, 26, 1212–1220. doi:10.1002/anie.198712121 |

| 52. | Moskau, D. Two-dimensional NMR correlation spectroscopy of quadrupolar nuclei. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany, 1987. |

| 53. | Vollhardt, J. Alkalimetal and titanium derivatives of sulfones: synthesis, structure and reactivity. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 1990. |

| 46. | Boche, G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1989, 28, 277–297. doi:10.1002/anie.198902771 |

| 47. | Linnert, M.; Bruhn, C.; Wagner, C.; Steinborn, D. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 691, 2358–2367. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.12.048 |

| 48. | Scholz, R.; Hellmann, G.; Rohs, S.; Raabe, G.; Runsink, J.; Özdemir, D.; Luche, O.; Heß, T.; Giesen, A. W.; Atodiresei, J.; Lindner, H. J.; Gais, H.-J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 4559–4587. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201000409 |

| 49. | Hellmann, G.; Hack, A.; Thiemermann, E.; Luche, O.; Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013, 19, 3869–3897. doi:10.1002/chem.201204014 |

| 50. | Gerhards, F.; Griebel, N.; Runsink, J.; Raabe, G.; Gais, H.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 17904–17920. doi:10.1002/chem.201503123 |

| 40. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14399–14408. doi:10.1039/c4dt01466a |

| 43. | Feichtner, K.-S.; Gessner, V. H. Inorganics 2016, 4, 40. doi:10.3390/inorganics4040040 |

| 55. | Streitwieser, A.; Bacharach, S. M.; Dorigo, A.; Schleyer, P. v. R. Bonding, Structure and Energetics in Organolithium Compounds. In Lithium Chemistry: A theoretical and experimental overview; Saps, A.-M.; Schleyer, P. v. R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp 1–43. |

| 56. | Glendening, E. D.; Shrout, A. L. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 4966–4972. doi:10.1021/jp058010f |

| 53. | Vollhardt, J. Alkalimetal and titanium derivatives of sulfones: synthesis, structure and reactivity. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 1990. |

| 1. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Mézailles, N. Stable Geminal Dianions as Precursors for Gem-Diorganometallic and Carbene Complexes. In Organo-di-Metallic Compounds (or Reagents); Xi, Z., Ed.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 47; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp 63–128. doi:10.1007/3418_2014_74 |

| 2. | Fustier-Boutignon, M.; Nebra, N.; Mézailles, N. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8555–8700. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00802 |

| 54. | Günther, H. High-resolution 6,7Li NMR of Organolithium Compounds. In Advanced Applications of NMR to Organometallic Chemistry; Gielen, M.; Willem, R.; Wrackmeyer, B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, U.K., 1996. |

| 15. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054 |

| 15. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054 |

| 15. | Gais, H.-J.; Vollhardt, J.; Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Lindner, H. J.; Braun, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 978–980. doi:10.1021/ja00211a054 |

| 51. | Günther, H.; Moskau, D.; Bast, P.; Schmalz, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1987, 26, 1212–1220. doi:10.1002/anie.198712121 |

| 52. | Moskau, D. Two-dimensional NMR correlation spectroscopy of quadrupolar nuclei. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany, 1987. |

| 53. | Vollhardt, J. Alkalimetal and titanium derivatives of sulfones: synthesis, structure and reactivity. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 1990. |

© 2020 Vollhardt et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)