Abstract

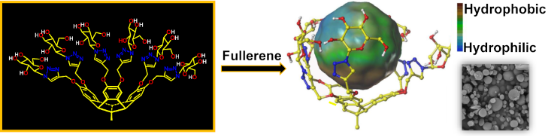

A sugar-functionalized water-soluble tribenzotriquinacene derivative bearing six glucose residues, TBTQ-(OG)6, was synthesized and its interaction with C60 and C70-fullerene in co-organic solvents and aqueous solution was investigated by fluorescence spectroscopy and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy. The association stoichiometry of the complexes TBTQ-(OG)6 with C60 and TBTQ-(OG)6 with C70 was found to be 1:1 with binding constants of Ka = (1.50 ± 0.10) × 105 M−1 and Ka = (2.20 ± 0.16) × 105 M−1, respectively. The binding affinity between TBTQ-(OG)6 and C60 was further verified by Raman spectroscopy. The geometry of the complex of TBTQ-(OG)6 with C60 deduced from DFT calculations indicates that the driving force of the complexation is mainly due to the hydrophobic effect and to host–guest π–π interactions. Hydrophobic surface simulations showed that TBTQ-(OG)6 and C60 forms an amphiphilic supramolecular host–guest complex, which further assembles to microspheres with diameters of 0.3–3.5 μm, as determined by scanning electron microscopy.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In the field of supramolecular chemistry, host–guest association through noncovalent interactions is an interesting and exciting topic, especially for the encapsulation of various fullerenes, such as C60 and C70 [1-5]. It is generally accepted that good complexation of fullerenes requires host molecules with bowl or basket-like shapes, such as calixarenes [6], corannulenes [7-10], cyclodextrins [11-13], cyclotriveratrylenes [14-16], and similar macrocycles [17-20]. Tribenzotriquinacene (TBTQ) and its derivatives, owing to their unique rigid, C3v-symmetric, concave-convex trifuso-triindane skeleton that consists of three perfectly orthogonally oriented indane wings, bear a similar potential as molecular hosts. TBTQ hydrocarbons are chemically stable and offer various possibilities for functionalization. Therefore, TBTQ derivatives have attracted much attention since the first synthesis reported in 1984 [21-24]. The arene periphery of the TBTQ framework bears a great and variable potential for the efficient expansion of the small and relatively shallow cavity of the parent TBTQ hydrocarbons, thus allowing for the inclusion of large guest molecules, such as the fullerenes. Several TBTQ derivatives with extended cavities have been developed by us and other groups. Volkmer et al. designed a series of novel TBTQ-based receptors, 1–3, and studied their binding affinities to C60 [25-28]. Georghiou et al. [29] synthesized the tris(thianthreno)-annelated triquinacene 4, and Cao et al. [30] constructed the tris(naphtho)triquinacene 5, bearing six annelated benzofuran units, and they investigated the supramolecular interaction of these hosts with fullerenes (Figure 1). All these TBTQ-based hosts were found to bind fullerenes in organic solvents with different strengths, as indicated by UV–vis or 1H NMR titration experiments. Moreover, easily accessible C3v-symmetrical sixfold hydroxy-functionalized TBTQ derivatives gain increasing attention for potential applications in host–guest recognition, such as gas storage and cationic complexation [31-33].

Figure 1: Selected TBTQ derivatives 1–5 that bind fullerenes in host–guest complexes.

Figure 1: Selected TBTQ derivatives 1–5 that bind fullerenes in host–guest complexes.

In the past years, the recognition of the biological and pharmaceutical relevance of fullerenes, such as their photodynamic activity, phototoxicity, HIV-1 protease inhibitor ability, and oxidative stability, has promoted the exploration of water-soluble fullerenes for biological use [34,35]. The extremely hydrophobic nature of fullerenes requires a strongly hydrophilic supramolecular host to achieve water solubility. It is important to note that host–guest research on TBTQ derivatives with fullerenes has been limited to organic media so far because of the poor solubility of their complexes in aqueous media. Therefore, the design, synthesis, and exploration of water-soluble TBTQ derivatives offer attractive possibilities for broadening the applications of the TBTQ structural motif. In the work presented here, we have introduced sugar motifs that possess good water solubility and biocompatibility [36-38] at the six outer peripheral positions of the TBTQ framework to provide, for the first time, a water-soluble TBTQ-based host bearing an extended cavity. The complexation of this host with C60 and C70-fullerene was investigated in co-organic solvents and in aqueous solution. The hydrophobic surface simulation of this host indicated the formation of a supra-amphiphilic system, which, as shown by scanning electron microscopy, further self-assembles into microspheres in the solid state. It is shown that the inclusion of fullerenes into the water-soluble TBTQ-based host greatly compensates for their water-repulsive nature and results in the formation of self-assembled microspheres that may have some potential for biological and pharmaceutical applications.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of the host TBTQ-(OG)6. The sugar-functionalized host TBTQ-(OG)6 was synthesized starting from the known compound TBTQ-(OH)6 (Scheme 1) [31-33]. The reaction of TBTQ-(OH)6 with propargyl bromide in the presence of potassium carbonate gave the hexakis-propargyl ether, TBTQ-(OP)6, in 31% yield. The subsequent CuAAC reaction with 1-azido-2,3,4,6-tetraacetylglucose, which was prepared according to the reported method [39], in the presence of Cu(I) as the catalyst afforded the acetyl-protected, sugar-functionalized derivative TBTQ-(OAcG)6 in 50% yield. As expected, compound TBTQ-(OAcG)6 exhibited good solubility in most organic solvents such as dichloromethane, chloroform, tetrahydrofuran, and DMSO, but it was insoluble in solvents like methanol, ethanol, and water. Compound TBTQ-(OAcG)6 was finally deacetylated with sodium methoxide in methanol to afford the desired six-fold sugar-functionalized derivative TBTQ-(OG)6 in 80% yield. The solubility of this compound was completely different from that of its acetylated precursor: it exhibited good solubility in DMF, DMSO, toluene/DMSO 1:1 (v/v) as well as in water.

Structural characterization. All synthesized compounds were fully characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (see Supporting Information File 1) and the data were found to be consistent with the proposed structures. For the hexakis-propargyl ether TBTQ-(OP)6, the signals at δ = 2.53 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum and at δ = 78.98 and 76.07 ppm in the 13C NMR spectrum were attributed to the acetylene protons and carbons, respectively. The electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrum showed the most intense peak at m/z 641.1923, which corresponds to the [M + Na]+ molecular adduct ion and matches well with the calculated value (m/z 641.1935, Δ = −1.8 ppm). In addition, the corresponding [M + K]+ ion appears at m/z 657.1709 (Δ = + 5.3 ppm). The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of compound TBTQ-(OAcG)6 dissolved in DMSO-d6 are noteworthy because they reflect the diastereotopic environment of the different molecular building blocks. For example, the 1H NMR spectrum of TBTQ-(OAcG)6 exhibits two singlet resonances at δ = 8.62 and δ = 8.58 ppm, each of which indicates three equivalent protons of the six triazole rings. Likewise, two singlets at δ = 7.33 and δ = 7.30 ppm are due to two sets of three equivalent arene protons of the TBTQ core [40]. The acetyl protons of the protected glucose residues appear as eight distinct resonances. The 13C NMR spectrum shows a similar splitting. The triazole carbons resonate at δ = 123.71 and δ = 123.69 ppm and at δ = 143.88 and δ = 143.79 ppm, indicating two sets of magnetically nonequivalent linkers. This is clearly a consequence of the prochiral nature of the TBTQ core. We also note that such splitting phenomenon was reported for neither six-fold sugar-functionalized cyclotriveratrylenes [41], which are directly comparable to TBTQ-(OAcG)6, nor for six-fold sugar-functionalized triptycene [42], and ten-fold sugar-functionalized pillar[5]arene [43]. Temperature-dependent 1H NMR spectroscopy of TBTQ-(OAcG)6 in DMSO-d6 was carried out in the range of 20–70 °C and revealed a slight decrease of the splitting of the aromatic proton resonances with increasing temperature, but no coalescence. While most of the resonances did not shift significantly, the triazole pair of singlets was shifted to higher field by Δδ = −0.14 ppm (see Figure S2 in Supporting Information File 1). All these observations reflect the molecular C3-symmetry of TBTQ-(OAcG)6 in solution and the presence of two diastereotopic sets of three magnetically equivalent tentacles at the rigid, prochiral TBTQ skeleton.

The mass spectrometric characterization of TBTQ-(OAcG)6 turned out to be quite difficult. The MALDI-(+) mass spectrum (see Figure S10 and Table S1 in Supporting Information File 1), recorded with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) as a matrix, exhibits the base peak at m/z 2879 along with an adjacent intense peak at m/z 2896, which are assigned to the [M + Na]+ and [M + K]+ molecular adduct ions, respectively. Unfortunately, attempts to perform accurate mass measurements were unsuccessful. However, the MALDI mass spectrum also shows the characteristic losses of up to at least three tentacle residues from both the [M + Na]+ and [M + K]+ molecular ions [44-46]. In contrast to the MALDI mass spectrum, the high-resolution ESI-(+) mass spectrum of TBTQ-(OAcG)6 (see Figure S11 and Table S2) exhibits a sole peak group with the maximum component at m/z 1505.9690 and Δ(m/z) = 0.5, indicating the presence of doubly charged ions. The most intense peak is assigned to the doubly charged [M + 1] isotopolog of the molecular adduct [M + 6H2O + 2Na]2+, the theoretical value of which is calculated to be m/z 1505.9611 (Δ = + 5.2 ppm). The surprising presence of six equivalents of water points to the formation of strong hydrogen bonds between the sugar ester bonds of TBTQ-(OAcG)6 and the water molecules as guests. However, the origin of this intriguing observation associated with the attachment of just two sodium cations requires further studies. Despite the unusual mass spectrometric behavior of the compound, the combined spectroscopic evidence strongly supports the identity of TBTQ-(OAcG)6.

After deprotection of the glucose units, the acetyl signals disappeared in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the target compound TBTQ-(OG)6. The 1H NMR spectrum showed characteristic resonances for the TBTQ core, the six triazole rings and the six glucose units but also some broadened signals. In contrast to the acetylated precursor, splitting of the proton signals is almost completely absent. At first glance, the 13C NMR spectrum exhibited only 14 of the 15 resonances expected for a C3-symmetric structure. However, a closer inspection revealed again a tiny splitting of several resonances, e.g., of those of the triazole rings at δ = 124.21 and δ = 124.24 ppm and at δ = 142.80 and δ = 142.82 ppm, but also for those of the benzene rings of the TBTQ core. Even the six resonances of the glucose carbons appear to split into two signals (e.g., at δ = 79.96 and δ = 79.98 ppm. Temperature-dependent 1H NMR spectroscopy of TBTQ-(OG)6 again revealed a similar upfield shift of the triazole resonance as that observed for the precursor (Δδ = −0.13 ppm). Even more significant upfield shifts were found for the resonances of the glucose protons with exception of the doublet of the glycosidic protons.

The MALDI-(+) mass spectrum of TBTQ-(OG)6 (see Figure S14 and Table S3, Supporting Information File 1) exhibits dominating [M + Na]+ and [M + K]+ molecular ion peaks at m/z 1871 and m/z 1887, respectively, in analogy to the spectrum of the precursor compound. Also, characteristic fragment ions peaks of minor intensity appear m/z 1709 and m/z 1628, indicating the elimination of a glucose unit as C6H10O5 (162 u) and, respectively, the loss of the entire tentacle as an C9H14N3O5· radical (244 u) from the [M + Na]+ ion followed by H atom transfer. Again, accurate mass measurements were not obtained. As another surprise, the high-resolution ESI-(−) mass spectrum of TBTQ-(OG)6 (see Figure S15 and Table S4, Supporting Information File 1) exhibits a prominent [M − 2 H]2− peak at m/z 923.3014 which is consistent with the calculated value (m/z 923.3045, Δ = −3.3 ppm). Together with the 1H and 13C NMR spectra this unambiguously confirms the successful synthesis of the host compound TBTQ-(OG)6.

Complexation of TBTQ-(OG)6 with fullerenes. In order to investigate the host–guest relationship between TBTQ-(OG)6 and fullerenes, fluorescence titration experiments were performed in toluene/DMSO 1:1 (v/v), in which both the host and the guest components could be dissolved, instead of in water. As shown in Figure 2, the spectrum of TBTQ-(OG)6 exhibits an emission maximum peak at 329 nm upon excitation at 294 nm. This emission band is probably due to the formation of the ground-state dimer by interaction between the benzene rings upon excitation or excimer emission caused by the interaction between the aromatic rings [41,43]. As the concentration of the fullerenes C60 and C70 increase, the emission is significantly quenched, indicating the photoinduced energy transfer from TBTQ-(OG)6 to the fullerenes [47,48]. Molar ratio plots (see Figure S16, Supporting Information File 1) on the basis of the fluorescence titration experiments suggested a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio of both TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 and TBTQ-(OG)6

C70, and the association constants were calculated to be Ka = (1.50 ± 0.10) × 105 M−1 and Ka = (2.20 ± 0.16) × 105 M−1, respectively, using a global nonlinear curve fitting method (Figure 2) [49]. The slightly stronger association affinity of C70-fullerene may be attributed to its larger size and surface area as compared to C60-fullerene [50].

![[1860-5397-16-207-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-207-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Fluorescence spectra of TBTQ-(OG)6 (5.0 × 10−6 M) with varying concentrations of (a) C60 and (b) C70 (0.0, 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 15.0, 20.0, 25.0, 35.0, 50.0 ×10−6 M) in toluene/DMSO 1:1 (v/v) (λex = 294 nm). The insets show the respective plots of ΔF vs [C60] and [C70] at 320 nm, 329 nm and 340 nm (the solid line was obtained from the global nonlinear curve fitting).

Figure 2: Fluorescence spectra of TBTQ-(OG)6 (5.0 × 10−6 M) with varying concentrations of (a) C60 and (b) C70...

The complexation between TBTQ-(OG)6 and fullerenes was also examined by UV–vis spectroscopy in both toluene/DMSO 1:1 (v/v) and water. Figure 3a shows the UV–vis spectra of TBTQ-(OG)6, C60 and TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 in toluene/DMSO. TBTQ-(OG)6 absorbs at 297 nm and C60 exhibits two absorption peaks at 298 nm and 333 nm. When C60 was mixed with TBTQ-(OG)6 in a 1:1 molar ratio, the absorption of C60 at 298 nm was slightly shifted to 302 nm. Similarly, the absorption of C70 at 298 nm was shifted to 301 nm after mixing the fullerenes with TBTQ-(OG)6 in the same molar ratio (Figure 3b). In aqueous solution, TBTQ-(OG)6 showed an absorption at 292 nm and, as expected, practically no absorption was observed for C60 and C70 due to their poor solubility (Figure 4a and Figure 4b). However, 1:1 molar mixture of TBTQ-(OG)6 and C60 in water exhibited an increased absorption at 292 nm and generated a new absorption band at 354 nm (Figure 4a). This observation is attributed to the increased solubility of C60 in water due to formation of the host–guest complex with TBTQ-(OG)6. A similar absorption behavior was observed for TBTQ-(OG)6

C70 (Figure 4b). The dispersibility of higher amounts of fullerenes in water in the presence of TBTQ-(OG)6 was further assessed at different rest times after sonication for 10 min. As illustrated in Figure S17 (Supporting Information File 1), the pristine C60 and C70-fullerenes precipitated rapidly within 5 min. In contrast, the TBTQ-(OG)6

C60 and TBTQ-(OG)6

C70 complexes showed improved water dispersibility of the fullerenes, which was maintained even after 20 days. The maximum solubility of C60 in water was measured to be about 0.14 mg/mL in the presence of ten equivalents of TBTQ-(OG)6, while the maximum solubility of C70 was about 0.17 mg/mL.

![[1860-5397-16-207-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-207-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3:

Absorption spectra of (a) TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 [TBTQ-(OG)6: 50 μM; C60: 50 μM] and (b) TBTQ-(OG)6

C70 [TBTQ-(OG)6: 50 μM; C70: 50 μM] in toluene/DMSO 1:1 (v/v) after centrifugation. The insets show the magnified partial UV curves in the range of 290–310 nm.

Figure 3:

Absorption spectra of (a) TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 [TBTQ-(OG)6: 50 μM; C60: 50 μM] and (b) TBTQ-(OG)6

C70 [...

![[1860-5397-16-207-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-207-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4:

Absorption spectra of (a) TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 [TBTQ-(OG)6: 50 μM; C60: 50 μM] and (b) TBTQ-(OG)6

C70 [TBTQ-(OG)6: 50 μM; C70: 50 μM] in water after centrifugation.

Figure 4:

Absorption spectra of (a) TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 [TBTQ-(OG)6: 50 μM; C60: 50 μM] and (b) TBTQ-(OG)6

C70 [...

Raman spectroscopy has proven to be a useful tool for the characterization of carbon nanomaterials [51,52]. The Raman spectra of TBTQ-(OG)6, C60 and TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 are displayed in Figure 5. The TBTQ-(OG)6 shows a weak peak at 1112 cm−1. The pristine C60-fullerene shows characteristic peaks at 494 cm−1 (Ag-breathing mode), 1467 cm−1 (Ag-pentagonal pinch mode), as well as signals at 272 cm−1 and 1572 cm−1 (Hg modes) [53]. The Raman spectrum of TBTQ-(OG)6

C60 clearly shows the presence of TBTQ-(OG)6 and fullerene, and the slight shift of the peaks further indicates the successful complexation of TBTQ-(OG)6 and C60.

![[1860-5397-16-207-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-207-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5:

Raman spectra of TBTQ-G6, C60 and TBTQ-G6 C60. Sample solutions of TBTQ-(OG)6 (50 μM) and TBTQ-(OG)6 (50 μM)

C60 (250 μM) were ultrasonicated for 10 min and then centrifuged to afford the supernatant, drops of which were dried on a slide glass. C60 was tested in powder form on a slide glass.

Figure 5:

Raman spectra of TBTQ-G6, C60 and TBTQ-G6 C60. Sample solutions of TBTQ-(OG)6 (50 μM) and TBTQ-(OG)...

Simulations of complex TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 in water. In spite of numerous attempts, we failed to obtain good-quality crystals to determine the binding conformation of complex TBTQ-(OG)6

C60 by X-ray diffraction. Therefore, the optimized geometry of the 1:1 complex of TBTQ-(OG)6

C60 in water was simulated by density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory, which was completed with the aid of Molclus, MOPAC, and ORCA 4.1.0 programs [54-56]. As shown in Figure 6, C60-fullerene can be embedded between the six arms of TBTQ-(OG)6 and the distance between the center of one benzene ring of the host and the closest five-membered ring of the guest was calculated to be 3.224 Å. The distances between the center of a triazole ring of TBTQ-(OG)6 and the adjacent five and six-membered rings of C60 were calculated to be 3.541 and 3.702 Å, respectively. These results suggest significant host–guest π–π interactions between TBTQ-(OG)6 and C60 [57]. In order to intuitively assess the hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of the complex, the hydrophobic surface diagram was generated and is reproduced in Figure 6c. It is evident that TBTQ-(OG)6 provides a strongly hydrophobic region at the inner bottom. Thus, the hydrophobic effect is assumed to be an important driving force for the formation of the complex TBTQ-(OG)6

C60.

![[1860-5397-16-207-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-207-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6:

Molecular model of the complex TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 in water, as generated by DFT calculations. (a) Side-view; (b) top-view; (c) hydrophobic surface diagram. In part, H atoms were omitted for clarity (yellow: C, red: O, blue: N, white: H for TBTQ-(OG)6; silver grey: C for C60).

Figure 6:

Molecular model of the complex TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 in water, as generated by DFT calculations. (a) Side...

Surface morphologies. The surface morphologies of C60, TBTQ-(OG)6, and TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in Figure 7a and 7b, respectively, the SEM image of C60-fullerene displays cylindrical nanotubes and that of TBTQ-(OG)6 does not indicate any definite shape. However, well-dispersed microspheres with diameters of 0.3–3.5 μm were observed for the complex TBTQ-(OG)6

C60. Obviously, these aggregates form by further assembly of the supra-amphiphilic host–guest systems, as suggested in Figure 6c, due to the hydrophobic interactions governing the association behavior of TBTQ-(OG)6

C60 in water.

![[1860-5397-16-207-7]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-16-207-7.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 7:

SEM images of (a) C60; (b) TBTQ-(OG)6; (c) and (d) TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 (C60: 1.4 mM; TBTQ-(OG)6: 1.4 mM in water, samples were freeze-dried and gold-sputtered before imaging).

Figure 7:

SEM images of (a) C60; (b) TBTQ-(OG)6; (c) and (d) TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 (C60: 1.4 mM; TBTQ-(OG)6: 1.4 mM...

Conclusion

In summary, we have successfully synthesized a six-fold sugar-functionalized, water soluble tribenzotriquinacene derivative, TBTQ-(OG)6, which significantly improves the solubility of C60 and C70-fullerenes in water. The target compound and its peracetylated precursor TBTQ-(OAcG)6 have been characterized in detail by NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. The host–guest complexation of TBTQ-(OG)6 with C60 and C70 takes place in a 1:1 molar ratio in both cases and with association constants of Ka = (1.50 ± 0.10) × 105 M−1 and Ka = (2.20 ± 0.16) × 105 M−1, respectively. It is suggested that the formation of the host–guest complexes is primarily due to hydrophobic effects and π–π interactions. The TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 complex was found to further assemble to microspheres with diameters of 0.3–3.5 μm. The inclusion complexation between TBTQ-(OG)6 and fullerenes in aqueous solution may shed light on potential future applications of fullerenes in biological and pharmaceutical areas.

Experimental

General information. All commercially available reagents were used as received unless otherwise stated. Anhydrous solvents were collected from a Mikrouna Solv Purer G3 solvent purification system. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz Bruker NMR spectrometer and chemical shifts were reported in ppm (δ). The fluorescence spectra were measured on a F97Pro fluorescence spectrophotometer (LengGuang Tech, Shanghai, China) and UV–vis spectra were measured on a UV-3300PC spectrometer (Mapada Instruments Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Mass spectra were recorded using either electrospray ionization (ESI) on a LCMS-IT-TOF instrument (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) or a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) on a RapifleX MALDI Tissuetyper system (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). Raman spectra were recorded on an inVia Reflex confocal Raman microscope (Renishaw plc, Wotton-under-Edge, UK) by dropping the sample solutions of TBTQ-(OG)6 and TBTQ-(OG)6 C60 onto a slide glass with subsequent air drying. C60 was tested in powder form on a slide glass. Ultrasonic mixing was performed with a 100 W ultrasonic cleaner. The surface morphology was investigated on a Phenom ProX scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Phenom World, Eindhoven, Netherlands). Samples were prepared from the freeze-dried aqueous solution/suspension of TBTQ-(OG)6, C60, and TBTQ-(OG)6

C60, and then gold-sputtered prior to imaging. Freeze drying was conducted on a Scientz-18N freeze dryer (Scientz Biotech, Zhejiang, China).

Synthesis of TBTQ-(OP)6. A mixture of TBTQ-(OH)6 (2.17 g, 5.56 mmol), potassium carbonate (9.23 g, 66.8 mmol), and propargyl bromide (5.40 g, 44.5 mmol, 98 wt %) in acetonitrile (100 mL) was stirred and heated under a nitrogen atmosphere at 70 °C for 12 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature and the suspension was filtered, and washed with acetonitrile. The resulting filtrate was evaporated under vacuum to afford the crude product as yellow solid. Further recrystallization from dichloromethane/ethanol provided the pure product as pale-yellow solid (1.06 g, 1.71 mmol, 31%). Mp 197.3–197.4 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.09 (s, 6H, HAr), 4.72 (dd, J = 3.7 Hz, J = 2.4 Hz, 12H, OCH2), 4.32 (s, 3H, Ar2CH), 2.53 (t, J = 2.3 Hz, 6H, C≡CH), 1.68 (s, 3H, CH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 147.87, 138.88, 111.49, 78.98, 76.07, 63.51, 63.12, 57.54, 27.47; HRESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C41H30NaO6+, 641.1935; found, 641.1923 (Δ = −1.8 ppm); [M + K]+ calcd for C41H30KO6+, 657.1674; found 657.1709 (Δ = +5.3 ppm).

Synthesis of TBTQ-(OAcG)6. A mixture of TBTQ-(OP)6 (201 mg, 0.33 mmol), 1-azido-2,3,4,6-tetraacetylglucose (1.48 g, 3.96 mmol), copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (52 mg, 0.21 mmol), and sodium ascorbate (28 mg, 0.14 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran/water cosolvent 2:1 (10 mL, v/v) was stirred vigorously under nitrogen in the dark at 60 °C for 24 h. Then, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and water (25 mL) was added to the mixture, which was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate and concentrated to dryness. The crude residue obtained was purified by silica gel column chromatography (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate 1:10; Rf = 0.6) to afford TBTQ-(OAcG)6 as off-white solid (470 mg, 0.16 mmol, 50%). Mp 141–148 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 20 °C) δ 8.62 (s, 3H), 8.58 (s, 3H), 7.33 (s, 3H), 7.30 (s, 3H), 6.37 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 6H), 5.73–5.67 (m, 6H), 5.57–5.53 (m, 6H), 5.24–5.15 (m, 18H), 4.36 (m, 6H), 4.19 (s, 3H), 4.18–4.13 (m, 6H), 4.09–4.06 (m, 6H), 2.038 (s, 9H), 2.033 (s, 9H), 1.971 (s, 9H), 1.967 (s, 9H), 1.963 (s, 9H), 1.94 (s, 9H), 1.75 (s, 9H), 1.66 (s, 9H), 1.54 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.04, 170.02, 169.59, 169.39, 169.36, 168.52, 168.51, 147.78, 147.76, 143.88, 143.79, 137.74, 123.71, 123.59, 110.56, 83.98, 83.91, 73.37, 73.35, 72.21, 72.19, 70.09, 67.54, 67.44, 62.57, 62.46, 62.20, 62.10, 61.72, 61.61, 59.77, 27.33, 20.43, 20.40. 20.38, 20.22, 19.80, 19.64; MALDI–MS (CHCA, m/z): 2879.5 (72), 2880.5 (100, both [M + Na]+), 2895.5 (24), 2896.5 (35), both [M + K]+), 2468.4 (39), 2469.4 (48), 2484.4 (16), 2485.4 (17), 2057.3 (29), 2058.3 (28), 2073.3 (13), 2074.3 (13), 1645.2 (8), 1646.2 (11), 1661.3 (5), 1662.3 (6)%; HRESIMS (m/z): [M + 6H2O + 2Na]2+ calcd for 12C1251H15614N1823Na216O662+, 1505.4594; found, 1505.4723 (Δ = +8.5 ppm); [M + 1] calcd for the ion containing one heavier isotope (mainly 13C112C1241H15614N1823Na216O662+) [M + 6H2O + 2Na]2+, 1505.9611; found, 1505.9690 (Δ = +5.2 ppm).

Synthesis of TBTQ-(OG)6. To a solution of TBTQ-(OAcG)6 (0.95 g, 0.33 mmol) in methanol (60 mL), sodium methoxide (about 1 mL) was added to adjust the pH value to 11. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h and then the suspension was filtered and washed with methanol. The filtrate was concentrated and purified by a Biogel P2 column to give TBTQ-(OG)6 as colorless solid (0.49 g, 0.26 mmol, 80%). Mp 226–227 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 20 °C) δ 8.46 (s, 6H), 7.47 (s, 6H), 5.56 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 6H), 5.44–5.41 (dd, J = 4.4 Hz, J = 6.3 Hz, 6H), 5.29 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 6H), 5.21–5.19 (m, 12 H), 5.17 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 6 H), 4.69–4.66 (m, 6H), 4.25 (s, 3H), 3.81–3.76 (m, 6H), 3.68–3.64 (m, 6H), 3.44–3.42 (m, 12H), 3.40–3.36 (m, 6H), 3.25–3.22 (m, 6H), 1.61 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 147.81, 147.77, 142.82, 142.80, 137.44, 124.24, 124.21, 109.88, 87.52, 79.98, 79.96, 76.95, 72.03, 69.50, 62.66, 62.60, 61.87, 61.78, 60.72, 27.53; MALDI–MS (CHCA, m/z): 1871.1 (95), 1872.1 (100, both [M + Na]+), 1887.1 (20), 1888.0 (20, both [M + K]+), 1709.1 (20), 1710.1 (21), 1628.1 (28), 1629.1 (24) %; HRESIMS (negative mode, m/z): [M – 2 H]2− calcd for C77H94N18O362−, 923.3045; found, 923.3014 (Δ = −3.3 ppm).

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: 1H NMR, 13C NMR spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry of all new compounds, and the xyz coordinates (in Å) of the complex of TBTQ-(OG)6 with C60. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.1 MB | Download |

References

-

Dawn, A.; Shiraki, T.; Ichikawa, H.; Takada, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Lien, L. T. N.; Shinkai, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2161–2171. doi:10.1021/ja211032m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kishi, N.; Akita, M.; Yoshizawa, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3604–3607. doi:10.1002/anie.201311251

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jia, F.; Li, D.-H.; Yang, T.-L.; Yang, L.-P.; Dang, L.; Jiang, W. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 336–339. doi:10.1039/c6cc09038a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Zheng, L.; Fang, W.; Chen, X.; Jiang, H. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14667–14675. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02674

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takeda, M.; Hiroto, S.; Yokoi, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Shinokubo, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6336–6342. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b02327

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Georghiou, P. E. Calixarenes and Fullerenes. In Calixarenes and Beyond; Neri, P.; Sessler, J.; Wang, M.-X., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp 879–919. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7_33

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sygula, A. Synlett 2016, 27, 2070–2080. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1562469

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yanney, M.; Fronczek, F. R.; Sygula, A. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 11305–11308. doi:10.1002/ange.201505327

Return to citation in text: [1] -

García-Calvo, V.; Cuevas, J. V.; Barbero, H.; Ferrero, S.; Álvarez, C. M.; González, J. A.; Díaz de Greñu, B.; García-Calvo, J.; Torroba, T. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 5803–5807. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01729

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lampart, S.; Roch, L. M.; Dutta, A. K.; Wang, Y.; Warshamanage, R.; Finke, A. D.; Linden, A.; Baldridge, K. K.; Siegel, J. S. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 14868–14872. doi:10.1002/ange.201608337

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ikeda, A.; Ishikawa, M.; Aono, R.; Kikuchi, J.-i.; Akiyama, M.; Shinoda, W. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 2534–2541. doi:10.1021/jo3027609

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mieda, S.; Ikeda, A.; Shigeri, Y.; Shinoda, W. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 12555–12561. doi:10.1021/jp5029905

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, W.; Gong, X.; Liu, C.; Piao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Diao, G. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 5107–5115. doi:10.1039/c4tb00560k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huerta, E.; Serapian, S. A.; Santos, E.; Cequier, E.; Bo, C.; de Mendoza, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 13496–13505. doi:10.1002/chem.201601690

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, M.-J.; Huang, C.-H.; Lai, C.-C.; Chiu, S.-H. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 6146–6149. doi:10.1021/ol3027957

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Feng, L.-J.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Han, B.-H. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 6985–6990. doi:10.1039/c3ra40432c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ferrero, S.; Barbero, H.; Miguel, D.; García-Rodríguez, R.; Álvarez, C. M. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 6183–6190. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b00362

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yuan, K.; Guo, Y.-J.; Zhao, X. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 5168–5179. doi:10.1021/jp5129657

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cui, S.; Huang, Q.; Wang, J.; Jia, H.; Huang, P.; Wang, S.; Du, P. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 5917–5921. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lu, X.; Gopalakrishna, T. Y.; Han, Y.; Ni, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wu, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5934–5941. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b00683

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuck, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1984, 23, 508–509. doi:10.1002/anie.198405081

Angew. Chem. 1984, 96, 515–516. doi:10.1002/ange.19840960725

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuck, D. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4885–4925. doi:10.1021/cr050546+

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tellenbröker, J.; Kuck, D. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011, 7, 329–337. doi:10.3762/bjoc.7.43

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Z.-M.; Tan, Y.; Ma, Y.-P.; Cao, X.-P.; Chow, H.-F.; Kuck, D. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 6478–6488. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c00396

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bredenkötter, B.; Henne, S.; Volkmer, D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2007, 13, 9931–9938. doi:10.1002/chem.200700915

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bredenkötter, B.; Grzywa, M.; Alaghemandi, M.; Schmid, R.; Herrebout, W.; Bultinck, P.; Volkmer, D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 9100–9110. doi:10.1002/chem.201304980

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Henne, S.; Bredenkötter, B.; Alaghemandi, M.; Bureekaew, S.; Schmid, R.; Volkmer, D. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 3855–3863. doi:10.1002/cphc.201402475

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Henne, S.; Bredenkötter, B.; Dehghan Baghi, A. A.; Schmid, R.; Volkmer, D. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 5995–6002. doi:10.1039/c2dt12435a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Georghiou, P. E.; Dawe, L. N.; Tran, H.-A.; Strübe, J.; Neumann, B.; Stammler, H.-G.; Kuck, D. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 9040–9047. doi:10.1021/jo801782z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, T.; Li, Z.-Y.; Xie, A.-L.; Yao, X.-J.; Cao, X.-P.; Kuck, D. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 3231–3238. doi:10.1021/jo2000918

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vile, J.; Carta, M.; Bezzu, C. G.; McKeown, N. B. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 2257–2260. doi:10.1039/c1py00294e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ng, C.-F.; Chow, H.-F.; Kuck, D.; Mak, T. C. W. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 2822–2827. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00278

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Greatorex, S.; Vincent, K. B.; Baldansuren, A.; McInnes, E. J. L.; Patmore, N. J.; Sproules, S.; Halcrow, M. A. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2281–2284. doi:10.1039/c8cc10122a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nakamura, E.; Isobe, H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 807–815. doi:10.1021/ar030027y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Strom, T. A.; Durdagi, S.; Ersoz, S. S.; Salmas, R. E.; Supuran, C. T.; Barron, A. R. J. Pept. Sci. 2015, 21, 862–870. doi:10.1002/psc.2828

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dondoni, A.; Marra, A. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4949–4977. doi:10.1021/cr100027b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, G.; Ma, Y.; Han, C.; Yao, Y.; Tang, G.; Mao, Z.; Gao, C.; Huang, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10310–10313. doi:10.1021/ja405237q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lai, C.-H.; Hütter, J.; Hsu, C.-W.; Tanaka, H.; Varela-Aramburu, S.; De Cola, L.; Lepenies, B.; Seeberger, P. H. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 807–811. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04984

Return to citation in text: [1] -

García-Viñuales, S.; Delso, I.; Merino, P.; Tejero, T. Synthesis 2016, 48, 3339–3351. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1562500

Return to citation in text: [1] -

The diastereotopicity of the chemically equivalent constituents of two adjacent tentaculas attached to the TBTQ core (e.g., to positions C2 and C3) arises from the prochirality of the TBTQ skeleton. Therefore, the triazole protons of the exemplary parent (M)- and (P)-enantiomers (R = H) shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information File 1) are enantiotopic. In the glucosylated derivatives TBTQ-(OAcG)6 and TBTQ-(OG)6 these protons and the elements of the sugar residues (R = ᴅ-glucosyl) are diastereotopic. See ref. [24] and previous work cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, F.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, Q.-Y.; Yan, C.-G.; Han, B.-H. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 971–976. doi:10.1021/jo202141a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Han, B.-H. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 3300–3307. doi:10.1039/c5nj03075g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Schönbeck, C.; Han, B.-H. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 19041–19047. doi:10.1039/c4ra07523d

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Because of the mass differences, Δ(m/z) = 411, found in the MALDI mass spectrum, it is assumed that the loss of each tentacula (glucosyl-triazolyl-CH2·, C17H22N3O9·, 412 u) is accompanied by reductive transfer of a hydrogen atom from the matrix to the corresponding fragment ion, e.g., [M + Na]+ (m/z 2979.5) → [M + Na − C17H22N3O9]+· (m/z 2467.4) → [M + Na − C17H22N3O9 + H]+ (m/z 2468.4), generating a phenolic hydroxyl group. Similar homolytic C–O bond cleavage of the [M + Na]+ molecular ions of benzyl aryl ethers have been observed in recent work (ref. [19]). The loss a second and a third tentacle leads to ions with m/z 2057 and m/z 1645, respectively, and an analogous series of sequential fragmentation of the [M + K]+ ions gives rise to ions with m/z 2484, m/z 2045 and m/z 1660.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuck, D.; Heitkamp, S.; Letzel, M.; Ahmed, I.; Krohn, K. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 24, 23–32. doi:10.1177/1469066717729300

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuck, D.; Heitkamp, S.; Sproß, J.; Letzel, M. C.; Ahmed, I.; Krohn, K.; Parker, R. G.; Wang, Y.; Robbins, V. J.; Ames, W. M.; Schettler, P. D.; Hark, R. R. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 377, 23–38. doi:10.1016/j.ijms.2014.06.013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Halder, A.; Bhatt, S.; Nayak, S. K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2011, 84, 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2011.08.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wolffs, M.; Hoeben, F. J. M.; Beckers, E. H. A.; Schenning, A. P. H. J.; Meijer, E. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13484–13485. doi:10.1021/ja054406t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, G.; Zhao, R.; Wu, D.; Zhang, F.; Shao, L.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Tang, G.; Chen, X.; Huang, F. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 6178–6188. doi:10.1039/c6py01402j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, S.-Q.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Fu, W.-F.; Liu, F.; Wang, C.-M.; Sheng, C.-Q.; Wang, Y.-F.; Deng, K.; Zeng, Q.-D.; Shu, L.-J.; Wan, J.-H.; Chen, H.-Z.; Russell, T. P. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11701–11713. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b06961

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Das, R. S.; Agrawal, Y. K. Vib. Spectrosc. 2011, 57, 163–176. doi:10.1016/j.vibspec.2011.08.003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ferrari, A. C.; Basko, D. M. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 235–246. doi:10.1038/nnano.2013.46

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 18102–18108. doi:10.1039/c8nj03970d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Molclus Program, Version 1.7; Tian Lu, http://www.keinsci.com/research/molclus.html.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

MOPAC2016; Stewart Computational Chemistry: Colorado Springs, CO, USA.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. doi:10.1002/wcms.81

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Janiak, C. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2000, 3885–3896. doi:10.1039/b003010o

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 57. | Janiak, C. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2000, 3885–3896. doi:10.1039/b003010o |

| 24. | Li, Z.-M.; Tan, Y.; Ma, Y.-P.; Cao, X.-P.; Chow, H.-F.; Kuck, D. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 6478–6488. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c00396 |

| 19. | Cui, S.; Huang, Q.; Wang, J.; Jia, H.; Huang, P.; Wang, S.; Du, P. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 5917–5921. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02055 |

| 1. | Dawn, A.; Shiraki, T.; Ichikawa, H.; Takada, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Lien, L. T. N.; Shinkai, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2161–2171. doi:10.1021/ja211032m |

| 2. | Kishi, N.; Akita, M.; Yoshizawa, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3604–3607. doi:10.1002/anie.201311251 |

| 3. | Jia, F.; Li, D.-H.; Yang, T.-L.; Yang, L.-P.; Dang, L.; Jiang, W. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 336–339. doi:10.1039/c6cc09038a |

| 4. | Sun, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Zheng, L.; Fang, W.; Chen, X.; Jiang, H. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14667–14675. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02674 |

| 5. | Takeda, M.; Hiroto, S.; Yokoi, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Shinokubo, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6336–6342. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b02327 |

| 14. | Huerta, E.; Serapian, S. A.; Santos, E.; Cequier, E.; Bo, C.; de Mendoza, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 13496–13505. doi:10.1002/chem.201601690 |

| 15. | Li, M.-J.; Huang, C.-H.; Lai, C.-C.; Chiu, S.-H. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 6146–6149. doi:10.1021/ol3027957 |

| 16. | Feng, L.-J.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Han, B.-H. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 6985–6990. doi:10.1039/c3ra40432c |

| 39. | García-Viñuales, S.; Delso, I.; Merino, P.; Tejero, T. Synthesis 2016, 48, 3339–3351. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1562500 |

| 11. | Ikeda, A.; Ishikawa, M.; Aono, R.; Kikuchi, J.-i.; Akiyama, M.; Shinoda, W. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 2534–2541. doi:10.1021/jo3027609 |

| 12. | Mieda, S.; Ikeda, A.; Shigeri, Y.; Shinoda, W. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 12555–12561. doi:10.1021/jp5029905 |

| 13. | Zhang, W.; Gong, X.; Liu, C.; Piao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Diao, G. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 5107–5115. doi:10.1039/c4tb00560k |

| 40. | The diastereotopicity of the chemically equivalent constituents of two adjacent tentaculas attached to the TBTQ core (e.g., to positions C2 and C3) arises from the prochirality of the TBTQ skeleton. Therefore, the triazole protons of the exemplary parent (M)- and (P)-enantiomers (R = H) shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information File 1) are enantiotopic. In the glucosylated derivatives TBTQ-(OAcG)6 and TBTQ-(OG)6 these protons and the elements of the sugar residues (R = ᴅ-glucosyl) are diastereotopic. See ref. [24] and previous work cited therein. |

| 7. | Sygula, A. Synlett 2016, 27, 2070–2080. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1562469 |

| 8. | Yanney, M.; Fronczek, F. R.; Sygula, A. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 11305–11308. doi:10.1002/ange.201505327 |

| 9. | García-Calvo, V.; Cuevas, J. V.; Barbero, H.; Ferrero, S.; Álvarez, C. M.; González, J. A.; Díaz de Greñu, B.; García-Calvo, J.; Torroba, T. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 5803–5807. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01729 |

| 10. | Lampart, S.; Roch, L. M.; Dutta, A. K.; Wang, Y.; Warshamanage, R.; Finke, A. D.; Linden, A.; Baldridge, K. K.; Siegel, J. S. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 14868–14872. doi:10.1002/ange.201608337 |

| 36. | Dondoni, A.; Marra, A. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4949–4977. doi:10.1021/cr100027b |

| 37. | Yu, G.; Ma, Y.; Han, C.; Yao, Y.; Tang, G.; Mao, Z.; Gao, C.; Huang, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10310–10313. doi:10.1021/ja405237q |

| 38. | Lai, C.-H.; Hütter, J.; Hsu, C.-W.; Tanaka, H.; Varela-Aramburu, S.; De Cola, L.; Lepenies, B.; Seeberger, P. H. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 807–811. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04984 |

| 6. | Georghiou, P. E. Calixarenes and Fullerenes. In Calixarenes and Beyond; Neri, P.; Sessler, J.; Wang, M.-X., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp 879–919. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7_33 |

| 31. | Vile, J.; Carta, M.; Bezzu, C. G.; McKeown, N. B. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 2257–2260. doi:10.1039/c1py00294e |

| 32. | Ng, C.-F.; Chow, H.-F.; Kuck, D.; Mak, T. C. W. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 2822–2827. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00278 |

| 33. | Greatorex, S.; Vincent, K. B.; Baldansuren, A.; McInnes, E. J. L.; Patmore, N. J.; Sproules, S.; Halcrow, M. A. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2281–2284. doi:10.1039/c8cc10122a |

| 29. | Georghiou, P. E.; Dawe, L. N.; Tran, H.-A.; Strübe, J.; Neumann, B.; Stammler, H.-G.; Kuck, D. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 9040–9047. doi:10.1021/jo801782z |

| 31. | Vile, J.; Carta, M.; Bezzu, C. G.; McKeown, N. B. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 2257–2260. doi:10.1039/c1py00294e |

| 32. | Ng, C.-F.; Chow, H.-F.; Kuck, D.; Mak, T. C. W. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 2822–2827. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00278 |

| 33. | Greatorex, S.; Vincent, K. B.; Baldansuren, A.; McInnes, E. J. L.; Patmore, N. J.; Sproules, S.; Halcrow, M. A. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2281–2284. doi:10.1039/c8cc10122a |

| 25. | Bredenkötter, B.; Henne, S.; Volkmer, D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2007, 13, 9931–9938. doi:10.1002/chem.200700915 |

| 26. | Bredenkötter, B.; Grzywa, M.; Alaghemandi, M.; Schmid, R.; Herrebout, W.; Bultinck, P.; Volkmer, D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 9100–9110. doi:10.1002/chem.201304980 |

| 27. | Henne, S.; Bredenkötter, B.; Alaghemandi, M.; Bureekaew, S.; Schmid, R.; Volkmer, D. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 3855–3863. doi:10.1002/cphc.201402475 |

| 28. | Henne, S.; Bredenkötter, B.; Dehghan Baghi, A. A.; Schmid, R.; Volkmer, D. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 5995–6002. doi:10.1039/c2dt12435a |

| 34. | Nakamura, E.; Isobe, H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 807–815. doi:10.1021/ar030027y |

| 35. | Strom, T. A.; Durdagi, S.; Ersoz, S. S.; Salmas, R. E.; Supuran, C. T.; Barron, A. R. J. Pept. Sci. 2015, 21, 862–870. doi:10.1002/psc.2828 |

| 21. |

Kuck, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1984, 23, 508–509. doi:10.1002/anie.198405081

Angew. Chem. 1984, 96, 515–516. doi:10.1002/ange.19840960725 |

| 22. | Kuck, D. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4885–4925. doi:10.1021/cr050546+ |

| 23. | Tellenbröker, J.; Kuck, D. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011, 7, 329–337. doi:10.3762/bjoc.7.43 |

| 24. | Li, Z.-M.; Tan, Y.; Ma, Y.-P.; Cao, X.-P.; Chow, H.-F.; Kuck, D. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 6478–6488. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c00396 |

| 17. | Ferrero, S.; Barbero, H.; Miguel, D.; García-Rodríguez, R.; Álvarez, C. M. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 6183–6190. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b00362 |

| 18. | Yuan, K.; Guo, Y.-J.; Zhao, X. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 5168–5179. doi:10.1021/jp5129657 |

| 19. | Cui, S.; Huang, Q.; Wang, J.; Jia, H.; Huang, P.; Wang, S.; Du, P. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 5917–5921. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02055 |

| 20. | Lu, X.; Gopalakrishna, T. Y.; Han, Y.; Ni, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wu, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5934–5941. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b00683 |

| 30. | Wang, T.; Li, Z.-Y.; Xie, A.-L.; Yao, X.-J.; Cao, X.-P.; Kuck, D. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 3231–3238. doi:10.1021/jo2000918 |

| 43. | Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Schönbeck, C.; Han, B.-H. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 19041–19047. doi:10.1039/c4ra07523d |

| 41. | Yang, F.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, Q.-Y.; Yan, C.-G.; Han, B.-H. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 971–976. doi:10.1021/jo202141a |

| 42. | Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Han, B.-H. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 3300–3307. doi:10.1039/c5nj03075g |

| 53. | Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 18102–18108. doi:10.1039/c8nj03970d |

| 54. | Molclus Program, Version 1.7; Tian Lu, http://www.keinsci.com/research/molclus.html. |

| 55. | MOPAC2016; Stewart Computational Chemistry: Colorado Springs, CO, USA. |

| 56. | Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. doi:10.1002/wcms.81 |

| 50. | Zhang, S.-Q.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Fu, W.-F.; Liu, F.; Wang, C.-M.; Sheng, C.-Q.; Wang, Y.-F.; Deng, K.; Zeng, Q.-D.; Shu, L.-J.; Wan, J.-H.; Chen, H.-Z.; Russell, T. P. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11701–11713. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b06961 |

| 51. | Das, R. S.; Agrawal, Y. K. Vib. Spectrosc. 2011, 57, 163–176. doi:10.1016/j.vibspec.2011.08.003 |

| 52. | Ferrari, A. C.; Basko, D. M. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 235–246. doi:10.1038/nnano.2013.46 |

| 47. | Halder, A.; Bhatt, S.; Nayak, S. K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2011, 84, 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2011.08.011 |

| 48. | Wolffs, M.; Hoeben, F. J. M.; Beckers, E. H. A.; Schenning, A. P. H. J.; Meijer, E. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13484–13485. doi:10.1021/ja054406t |

| 49. | Yu, G.; Zhao, R.; Wu, D.; Zhang, F.; Shao, L.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Tang, G.; Chen, X.; Huang, F. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 6178–6188. doi:10.1039/c6py01402j |

| 44. | Because of the mass differences, Δ(m/z) = 411, found in the MALDI mass spectrum, it is assumed that the loss of each tentacula (glucosyl-triazolyl-CH2·, C17H22N3O9·, 412 u) is accompanied by reductive transfer of a hydrogen atom from the matrix to the corresponding fragment ion, e.g., [M + Na]+ (m/z 2979.5) → [M + Na − C17H22N3O9]+· (m/z 2467.4) → [M + Na − C17H22N3O9 + H]+ (m/z 2468.4), generating a phenolic hydroxyl group. Similar homolytic C–O bond cleavage of the [M + Na]+ molecular ions of benzyl aryl ethers have been observed in recent work (ref. [19]). The loss a second and a third tentacle leads to ions with m/z 2057 and m/z 1645, respectively, and an analogous series of sequential fragmentation of the [M + K]+ ions gives rise to ions with m/z 2484, m/z 2045 and m/z 1660. |

| 45. | Kuck, D.; Heitkamp, S.; Letzel, M.; Ahmed, I.; Krohn, K. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 24, 23–32. doi:10.1177/1469066717729300 |

| 46. | Kuck, D.; Heitkamp, S.; Sproß, J.; Letzel, M. C.; Ahmed, I.; Krohn, K.; Parker, R. G.; Wang, Y.; Robbins, V. J.; Ames, W. M.; Schettler, P. D.; Hark, R. R. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 377, 23–38. doi:10.1016/j.ijms.2014.06.013 |

| 41. | Yang, F.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, Q.-Y.; Yan, C.-G.; Han, B.-H. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 971–976. doi:10.1021/jo202141a |

| 43. | Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Schönbeck, C.; Han, B.-H. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 19041–19047. doi:10.1039/c4ra07523d |

© 2020 Liu et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)