Abstract

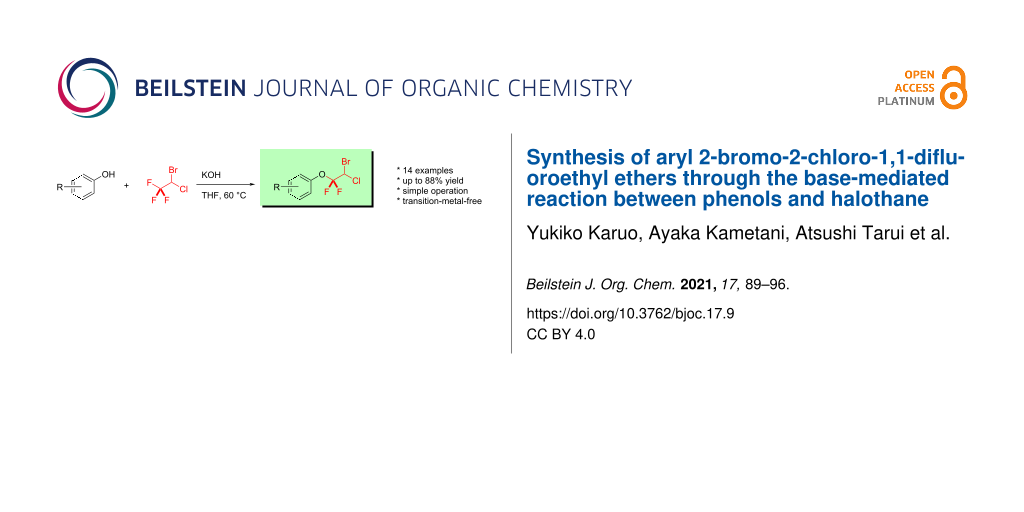

An efficient and convenient method for the synthesis of structurally unique and highly functionalized aryl 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1-difluoroethyl ethers has been developed. This approach exhibits a broad reaction scope, a simple operation and without the need of any expensive transition-metal catalyst, highly toxic or corrosive reagents. Notably, we demonstrate the potential utility of halothane for the synthesis of aryl gem-difluoroalkyl ethers containing the bromochloromethyl group.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Molecules containing fluoroalkyl groups are of interest in pharmaceutical and agrochemical sciences because deliberately incorporated fluorine atoms often change the chemical properties of the parent molecules by improving the absorption, resistance to metabolism, and pharmacological activities. To date, difluoromethyl or difluoromethylene compounds have been studied extensively as well as monofluorinated and trifluoromethylated arenes or aliphatics [1-4]. Recent progress in difluoromethylene chemistry successfully led to the finding of bioactive compounds such as pantoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor [5], and AFP-07, a prostaglandin I2 receptor-selective agonist [6-8], which suggests the importance of the difluoromethylene unit in drug discovery (Figure 1). There have been many reports for the construction of the difluoromethylene unit, such as the deoxygenating conversion of a carbonyl group to the difluoromethylene unit using N,N-diethylaminosulfur trifluoride (DAST) [9-14], the Reformatsky reaction of ethyl bromodifluoroacetate [15-23], and transformations of tetrafluoroethylene using suitable metal catalysts [24-31]. Additionally, recent advances in difluoromethylene chemistry have demonstrated the synthesis of aryl fluoroalkyl ethers as shown in Scheme 1 [32-34]. For example, the reactions of phenols with “gem-difluorocarbene precursors (route (a))” or “bromodifluoroalkyl compounds (route (b))” have been typically used to obtain a variety of aryl gem-difluoromethyl ethers. Particularly, the latter approach is useful for obtaining liquid crystal materials [35-38]. In the case of using 2-chloro-3,3,3-trifluoroprop-1-ene (route (c), Scheme 1), the aryl enol ether with a trifluoromethyl group was obtained [39,40]. A further example for the formation of an aryl fluoroalkyl ether was the reaction of phenol with 2-chloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane, also known as HCFC-133a, in the presence of potassium hydroxide (KOH) to give the gem-difluoromethyl ethers along with the formation of 1-fluoro-2-chlorovinyl ether (route (d), Scheme 1) [41]. On the basis of our previous reports, we focused on halothane, 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane, because the treatment of this compound with several bases was found to provide the highly electrophilic 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1-difluoroethene [42,43]. Additionally, another report discussed the carbocationic character of the gem-difluorovinyl carbon that was explained by an orbital interaction between the n orbital (fluorine) and the π orbital [44]. A literature survey revealed that Yagupol’skii et al. have achieved the first synthesis of aryl or alkyl 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1-difluoroethyl ethers by the reaction of alcohols with halothane as shown in Scheme 2 [45]. This study had a large impact on fluorine chemistry in terms of the availability of halothane to build difluoroalkyl ethers. However, these reactions have significant drawbacks such as the need of harsh reaction conditions, low chemical yields, and in particular, very few examples to understand the reaction profile (Scheme 2). To address this issue, we conducted extensive research to provide a general use of halothane for the construction of such difluoroalkyl ethers. In this paper, we discuss a new and practical synthetic approach to structurally unique and highly functionalized aryl 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1-difluoroethyl ethers as well as several considerations of the reaction mechanism.

Figure 1: Medical compounds having a difluoromethyl group.

Figure 1: Medical compounds having a difluoromethyl group.

Scheme 1: Methods for the synthesis of ethers containing fluorine substituents.

Scheme 1: Methods for the synthesis of ethers containing fluorine substituents.

Scheme 2: The previous work reported by Yagupol’skii et al.

Scheme 2: The previous work reported by Yagupol’skii et al.

Results and Discussion

We began our study to optimize the reaction conditions (Table 1). When two equivalents of halothane and sodium hydride (NaH) were treated with phenol (1a) at room temperature for 20 h, the reaction provided the ether product 2a in 39% yield (Table 1, entry 1). In this case, some of the substrate phenol remained in the reaction mixture. Therefore, the reactions were conducted with an increased amount of halothane (2.5 and 4.0 equivalents). However, in both reactions, the yield of the product 2a was not improved in spite of a significant decrease of the starting material, phenol (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). Next, as shown in entry 4 of Table 1, when the reaction was conducted with a lower loading of NaH, the desired product 2a was obtained in the same yield as that in entry 1 (Table 1). From the result of entry 5 (Table 1) in which the reaction time was prolonged to 52 h, the reaction was considered to be sluggish because the yield of 2a was only slightly better (55%). On the other hand, when the reaction temperature was raised to 40 or 60 °C, the product yield was gradually improved (Table 1, entries 6 and 7). It is worth noting that when changing the base to KOH, a dramatic improvement of the reaction efficiency was observed giving product 2a in 74% yield, even though the reaction time was remarkably short (Table 1, entry 8). On the contrary, the reaction did not occur at all when potassium carbonate was used as a base, because the deprotonation of phenol became slow due to the low basicity (Table 1, entry 9).

Table 1: Optimization of the reaction conditions with phenol (1a).

|

|

||||

| entry | base (equiv) | temp. (°C) | time (h) | yield (%)a |

| 1 | NaH (2.0) | rt | 20 | 39 |

| 2b | NaH (2.0) | rt | 23 | 37 |

| 3c | NaH (2.0) | rt | 23 | 32 |

| 4 | NaH (1.5) | rt | 24 | 39 |

| 5 | NaH (1.5) | rt | 52 | 55 |

| 6 | NaH (1.5) | 40 | 25 | 54 |

| 7 | NaH (1.5) | 60 | 13 | 74 |

| 8 | KOH (1.5) | 60 | 1.5 | 74 |

| 9 | K2CO3 (1.5) | 60 | 24 | 0 |

aIsolated yields. bHalothane (2.5 equiv) was used. cHalothane (4.0 equiv) was used.

With the optimal reaction conditions (Table 1, entry 8) in hand, we next examined the scope of the reaction (Table 2). When an electron-rich phenol, p-methoxyphenol (1b) was used, the reaction proceeded to afford ether 2b in 79% yield (Table 2, entry 1). An ortho-substitution with the bulkier tert-butyl group slightly affected the reaction giving product 2c in still acceptable yield (47%, Table 2, entry 2). p-Nitrophenol (1d), which is an electron-poor phenol, was converted into the corresponding ether 2d only in traces (Table 2, entry 3). By using 3.0 equivalents of KOH, p-trifluoromethylphenol (1e) provided the product 2e in 48% yield (Table 2, entry 4). Also a phenol possessing a base-labile ester group (1f) afforded the product 2f in 47% yield without the loss of the ester moiety (Table 2, entry 5). However, the reaction between p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (1g) and halothane did not proceed at all (Table 2, entry 6). A phenyl group in the ortho position (1h) did not affect the reaction and also the positional isomers 1i and 1j, gave the corresponding products in comparably high yields (Table 2, entries 7–9). Also, 1-naphthol (1k) was compatible with the reaction conditions giving the product 2k in a good yield of 85% (Table 2, entry 10). As shown in entries 11–13 (Table 2), o-iodophenol (1l) and the alkenyl-substituted phenols 1m and 1n, all substrates that are susceptible to radical conditions, afforded the corresponding iodo- and alkenyl-substituted products, suggesting the reaction proceeds through an ionic process. 2-Hydroxychalcone (1o), which is a good Michael acceptor, also participated in the reaction to give the product 2o in 56% yield, without byproduct formation from a Michael reaction (Table 2, entry 14). When o-aminophenol (1p) was used as the substrate, the coupling reaction occurred on the hydroxy group exclusively to give 2p (Table 2, entry 15).

Table 2: The reaction scope with various phenols.

|

|

||||

| entry | phenol | products | time (h) | yield (%)a |

| 1 |

1b |

2b |

2.5 | 79 |

| 2 |

1c |

2c |

0.5 | 47 |

| 3b |

1d |

2d |

20.5 | 3 |

| 4b |

1e |

2e |

7 | 48 |

| 5b |

1f |

2f |

13 | 47 |

| 6b |

1g |

2g |

24 | no reaction |

| 7 |

1h |

2h |

3 | 71 |

| 8 |

1i |

2i |

1.5 | 79 |

| 9 |

1j |

2j |

5 | 88 |

| 10 |

1k |

2k |

3.5 | 85 |

| 11 |

1l |

2l |

6.5 | 67 |

| 12 |

1m |

2m |

1.5 | 81 |

| 13c |

1n |

2n |

1 | 71 |

| 14b |

1o |

2o |

20 | 56 |

| 15 |

1p |

2p |

19 | 51 |

aIsolated yield. bKOH (3.0 equiv) was used. c1n and 2n were cis–trans mixtures.

To show the synthetic advantages of the obtained gem-difluoro ethers 2, we examined the further application of compound 2o in a cyclization reaction. Upon the treatment of 2o with zinc and chlorotrimethylsilane (TMSCl), the intramolecular 1,4-addition reaction of 2o proceeded to give the 2,2-gem-difluorochromane 3 in low yield (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3: Intramolecular 1,4-addition of 2o.

Scheme 3: Intramolecular 1,4-addition of 2o.

Next, we moved on consideration of the reaction mechanism as shown in Scheme 4a. The reaction was carried out in a stepwise procedure in which the phenoxide was prepared by mixing equimolar amounts of phenol (1a) and NaH to consume all NaH in the reaction mixture, and then halothane was added to the reaction mixture. The stepwise reaction gave the product 2a in 27% yield and 1a was recovered in 54% (Scheme 4a). Based on these results, we speculated that the initially generated phenoxide 4 or potassium hydroxide remaining in the reaction mixture could deprotonate halothane to provide the fully halogenated ethylene 5 (Scheme 4b) [32,33,45]. Recent studies demonstrated an electrophilic character of a gem-difluorovinyl carbon due to the overlapping of the fluorine lone pairs and the adjacent π orbital in favor of the generation of a difluoromethyl cation species [44]. Considering these reports, the phenoxide attack on the gem-difluorovinyl carbon atom is a reasonable process to forward the reaction with the generation of carbanion 6. Finally, the protonation of 6 by 1 or other acidic compounds, such as water molecules present in the reaction medium, would provide 2.

Conclusion

We exploited the reaction of various phenols with halothane to obtain aryl 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1-difluoroethyl ethers. The products are structurally unique and represent highly functionalized compounds containing the gem-difluoroalkyl ether unit in addition to a bromochloromethyl group. The reaction proceeds under mild conditions and is compatible with variously substituted phenols giving the products in moderate to good yields. Additionally, the products are expected to undergo a variety of functionalization using ionic and radical processes. Further studies on the chemical transformations of the ether products are currently underway.

Experimental

General information

1H NMR, 13C NMR and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on JEOL ECZ 400S spectrometers. Chemical shifts of 1H NMR are reported in ppm from tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. Chemical shifts of 13C NMR are reported in ppm from the center line of the triplet at 77.16 ppm for deuteriochloroform. Chemical shifts of 19F NMR are reported in ppm from CFCl3 as an internal standard. All data are reported as follows: chemical shifts, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, sep = septet, br = broad, brd = broad-doublet, m = multiplet), coupling constants (Hz), relative integration value. Mass spectra were obtained on a JEOL JMS-700T spectrometer (EI).

Materials

All commercially available materials were used as received without further purification. All experiments were carried out under argon atmosphere in flame-dried glassware using standard inert techniques for introducing reagents and solvents unless otherwise noted.

Typical procedure for the reaction between various phenols and halothane

To a solution of the phenol (1.0 mmol) in THF (5.0 mL) was added previously ground KOH (1.5 mmol) and halothane (2.0 mmol) in small portions at 0 °C. The solution was heated to 60 °C until the reaction was completed. Then, the reaction mixture was quenched by the addition of sat. aq. NH4Cl (20 mL) at 0 °C and extracted with AcOEt. The organic phase was washed with brine (30 mL), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography to afford the products 2.

2-Bromo-2-chloro-1,1-difluoroethyl phenyl ether (2a): The title product 2a was purified by column chromatography and preparative TLC (hexane only) and obtained in 74% yield (199.6 mg). Pale yellow oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.91 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.31 (m, 5H), 7.35–7.42 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 53.5 (t, J = 41.7 Hz), 119.7 (t, J = 267.1 Hz), 121.8, 126.5, 129.7, 149.7; 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −77.9 (dd, J = 136.9, 5.2 Hz, 1F), −78.2 (dd, J = 136.9, 5.2 Hz, 1F); EIMS (m/z): 270, 272 [M]+; HRMS–EI (m/z): [M]+ calcd for C8H6BrClF2O, 269.9259, 271.9238; found, 269.9264, 271.9233.

4-Benzoylmethyl-3-chloro-2,2-difluorochromane (3): To a solution of 2o (210.8 mg, 0.53 mmol) in THF (2.6 mL) was added zinc (42.1 mg, 0.64 mmol) and chlorotrimethylsilane (133 μL, 1.05 mmol) at 0 °C. After stirring for 40 min, the reaction mixture was quenched by the addition of 10% aq. HCl (40 mL) at 0 °C and extracted with AcOEt. The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexane/CHCl3 4:1 to 1:1) and product 3 was obtained as a mixture of two diastereoisomers (syn/anti 2:1) in 21% yield (36.9 mg). Yellow oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.48 (ddd, J = 18.7, 5.2, 1.4 Hz, anti-isomer), 3.73 (ddd, J = 18.7, 7.0, 1.2 Hz, anti-isomer, 2H), 3.57–3.71 (m, syn-isomer, 2H), 4.04–4.18 (m, anti-isomer, 1H), 4.29–4.37 (m, syn-isomer, 1H), 4.66 (ddd, J = 7.0, 6.0, 1.0 Hz, anti-isomer, 1H), 4.82 (t, J = 4.1 Hz, syn-isomer, 1H), 7.01–7.22 (m, 3H), 7.24–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, anti-isomer, 2H), 7.52 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, syn-isomer, 2H), 7.58–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.97 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.3 Hz, anti-isomer, 2H), 8.05 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.3 Hz, syn-isomer, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 34.5 (syn-isomer), 38.4 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, syn-isomer), 39.3 (anti-isomer), 41.7 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, anti-isomer), 54.7 (d, J = 28.6 Hz, anti-isomer), 54.9 (d, J = 26.6 Hz, syn-isomer), 55.1 (d, J = 28.6 Hz, anti-isomer), 55.3 (d, J = 26.6 Hz, syn-isomer), 117.3 (syn-isomer), 117.4 (anti-isomer), 119.49 (d, J = 256.9 Hz, anti-isomer), 119.52 (d, J = 251.1 Hz, syn-isomer), 120.6 (syn-isomer), 121.5 (anti-isomer), 122.06 (d, J = 256.9 Hz, anti-isomer), 122.11 (d, J = 251.1 Hz, syn-isomer), 124.1 (syn-isomer), 124.3 (anti-isomer), 127.0 (anti-isomer), 128.2 (syn-isomer), 128.3, 129.0, 129.1 (anti-isomer), 129.3 (syn-isomer), 133.9, 136.4 (anti-isomer), 136.5 (syn-isomer), 149.2 (anti-isomer), 149.6 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, syn-isomer), 197.0 (anti-isomer), 197.3 (syn-isomer); 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −69.0 (dd, J = 155.8, 4.1 Hz, syn-isomer, 1F), −70.8 (d, J = 157.3 Hz, anti-isomer, 1F), −77.6 (ddd, J = 157.6, 7.0, 4.2 Hz, anti-isomer, 1F), −79.0 (dd, J = 155.8, 3.1 Hz, syn-isomer, 1F); EIMS (m/z): 322 [M]+; HRMS–EI (m/z): [M]+ calcd for C17H13ClF2O2, 322.0572; found, 322.0565.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Characterization data for 2b–p and copies of 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.1 MB | Download |

References

-

Wang, J.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Aceña, J. L.; del Pozo, C.; Sorochinsky, A. E.; Fustero, S.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. doi:10.1021/cr4002879

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dreyer, G. B.; Metcalf, B. W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 6885–6888. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)88466-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hamer, R. R. L.; Freed, B.; Allen, C. R. Alkylamino- and alkylamino alkyl diarylketones. U.S. Pat. Appl. US5,006,563A, April 9, 1991.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Han, C.; Salyer, A. E.; Kim, E. H.; Jiang, X.; Jarrard, R. E.; Powers, M. S.; Kirchhoff, A. M.; Salvador, T. K.; Chester, J. A.; Hockerman, G. H.; Colby, D. A. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2456–2465. doi:10.1021/jm301805e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kohl, B.; Sturm, E.; Senn-Bilfinger, J.; Simon, W. A.; Krüger, U.; Schaefer, H.; Rainer, G.; Figala, V.; Klemm, K. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35, 1049–1057. doi:10.1021/jm00084a010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nakano, T.; Makino, M.; Morizawa, Y.; Matsumura, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1996, 35, 1019–1021. doi:10.1002/anie.199610191

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chang, C.-S.; Negishi, M.; Nakano, T.; Morizawa, Y.; Matsumura, Y.; Ichikawa, A. Prostaglandins 1997, 53, 83–90. doi:10.1016/s0090-6980(97)00003-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsumura, Y.; Nakano, T.; Asai, T.; Morizawa, Y. Synthesis and Properties of Novel Fluoroprostacyclins. In Biomedical Frontiers of Fluorine Chemistry; Ojima, I.; McCarthy, J. R.; Welch, J. T., Eds.; ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 639; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp 83–94. doi:10.1021/bk-1996-0639.ch006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Middleton, W. J. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 574–578. doi:10.1021/jo00893a007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lal, G. S.; Pez, G. P.; Pesaresi, R. J.; Prozonic, F. M.; Cheng, H. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 7048–7054. doi:10.1021/jo990566+

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lal, G. S.; Lobach, E.; Evans, A. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4830–4832. doi:10.1021/jo000020j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Singh, R. P.; Twamley, B.; Shreeve, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 1918–1924. doi:10.1021/jo016245r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

L’Heureux, A.; Beaulieu, F.; Bennett, C.; Bill, D. R.; Clayton, S.; LaFlamme, F.; Mirmehrabi, M.; Tadayon, S.; Tovell, D.; Couturier, M. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3401–3411. doi:10.1021/jo100504x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Umemoto, T.; Singh, R. P.; Xu, Y.; Saito, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18199–18205. doi:10.1021/ja106343h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hallinan, E. A.; Fried, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 2301–2302. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)80239-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Taguchi, T.; Kitagawa, O.; Suda, Y.; Ohkawa, S.; Hashimoto, A.; Iitaka, Y.; Kobayashi, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 5291–5294. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)80740-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Baldwin, J. E.; Lynch, G. P.; Schofield, C. J. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1991, 736–738. doi:10.1039/c39910000736

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Angelastro, M. R.; Bey, P.; Mehdi, S.; Peet, N. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1992, 2, 1235–1238. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(00)80220-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Curran, T. T. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 6360–6363. doi:10.1021/jo00075a033

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, Y.; Qi, M. J. Fluorine Chem. 1994, 67, 229–232. doi:10.1016/0022-1139(93)02961-d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kanai, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Honda, T. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2549–2551. doi:10.1021/ol006268c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sato, K.; Tarui, A.; Matsuda, S.; Omote, M.; Ando, A.; Kumadaki, I. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 7679–7681. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.09.031

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Poisson, T.; Belhomme, M.-C.; Pannecoucke, X. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9277–9285. doi:10.1021/jo301873y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Saijo, H.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15158–15161. doi:10.1021/ja5093776

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohashi, M.; Kawashima, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Kikushima, K.; Ogoshi, S. Organometallics 2015, 34, 1604–1607. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00218

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohashi, M.; Shirataki, H.; Kikushima, K.; Ogoshi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6496–6499. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b03587

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kawashima, T.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17795–17798. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b12007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kawashima, T.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17423–17427. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b11671

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohashi, M.; Ishida, N.; Ando, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Shigaki, A.; Kikushima, K.; Ogoshi, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 9794–9798. doi:10.1002/chem.201802415

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shirataki, H.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 1883–1887. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201801721

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shirataki, H.; Ono, T.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 851–856. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03674

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tarrant, P.; Brown, H. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 5831–5833. doi:10.1021/ja01156a111

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, X.; Pan, H.; Jiang, X. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 4937–4940. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)91263-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Ohashi, M.; Adachi, T.; Ishida, N.; Kikushima, K.; Ogoshi, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11911–11915. doi:10.1002/anie.201703923

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Segall, Y. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 5278–5283. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.04.082

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fuchibe, K.; Koseki, Y.; Sasagawa, H.; Ichikawa, J. Chem. Lett. 2011, 40, 1189–1191. doi:10.1246/cl.2011.1189

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sasada, Y.; Shimada, T.; Ushioda, M.; Matsui, S. Liq. Cryst. 2007, 34, 569–576. doi:10.1080/02678290701284279

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanaka, H.; Endou, H. Liquid crystal compound, liquid crystal composition and liquid crystal display element. Japanese Patent JPWO2014/129268, Aug 28, 2014.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hiraoka, Y.; Kawasaki-Takasuka, T.; Morizawa, Y.; Yamazaki, T. J. Fluorine Chem. 2015, 179, 71–76. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2015.05.006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dai, K.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.-G.; Liu, Z.-W.; Lu, J.; Liu, Z.-T. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4721–4728. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00396

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, K.; Chen, Q.-Y. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 4077–4084. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(02)00257-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nishihara, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Maruyama, N.; Sato, K.; Omote, M.; Ando, A.; Kumadaki, I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2003, 122, 247–249. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(03)00053-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ando, A.; Takahashi, J.; Nakamura, Y.; Maruyama, N.; Nishihara, M.; Fukushima, K.; Moronaga, J.; Inoue, M.; Sato, K.; Omote, M.; Kumadaki, I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2003, 123, 283–285. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(03)00148-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ichikawa, J.; Kaneko, M.; Yokota, M.; Itonaga, M.; Yokoyama, T. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3167–3170. doi:10.1021/ol060912r

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gerus, I. I.; Kolycheva, M. T.; Yagupol’skii, Y. L.; Kukhar, V. P. Zh. Org. Khim. 1989, 25, 2020–2021.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2]

| 1. | Wang, J.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Aceña, J. L.; del Pozo, C.; Sorochinsky, A. E.; Fustero, S.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Liu, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. doi:10.1021/cr4002879 |

| 2. | Dreyer, G. B.; Metcalf, B. W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 6885–6888. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)88466-x |

| 3. | Hamer, R. R. L.; Freed, B.; Allen, C. R. Alkylamino- and alkylamino alkyl diarylketones. U.S. Pat. Appl. US5,006,563A, April 9, 1991. |

| 4. | Han, C.; Salyer, A. E.; Kim, E. H.; Jiang, X.; Jarrard, R. E.; Powers, M. S.; Kirchhoff, A. M.; Salvador, T. K.; Chester, J. A.; Hockerman, G. H.; Colby, D. A. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2456–2465. doi:10.1021/jm301805e |

| 15. | Hallinan, E. A.; Fried, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 2301–2302. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)80239-2 |

| 16. | Taguchi, T.; Kitagawa, O.; Suda, Y.; Ohkawa, S.; Hashimoto, A.; Iitaka, Y.; Kobayashi, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 5291–5294. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)80740-6 |

| 17. | Baldwin, J. E.; Lynch, G. P.; Schofield, C. J. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1991, 736–738. doi:10.1039/c39910000736 |

| 18. | Angelastro, M. R.; Bey, P.; Mehdi, S.; Peet, N. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1992, 2, 1235–1238. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(00)80220-6 |

| 19. | Curran, T. T. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 6360–6363. doi:10.1021/jo00075a033 |

| 20. | Shen, Y.; Qi, M. J. Fluorine Chem. 1994, 67, 229–232. doi:10.1016/0022-1139(93)02961-d |

| 21. | Kanai, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Honda, T. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2549–2551. doi:10.1021/ol006268c |

| 22. | Sato, K.; Tarui, A.; Matsuda, S.; Omote, M.; Ando, A.; Kumadaki, I. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 7679–7681. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.09.031 |

| 23. | Poisson, T.; Belhomme, M.-C.; Pannecoucke, X. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9277–9285. doi:10.1021/jo301873y |

| 44. | Ichikawa, J.; Kaneko, M.; Yokota, M.; Itonaga, M.; Yokoyama, T. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3167–3170. doi:10.1021/ol060912r |

| 9. | Middleton, W. J. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 574–578. doi:10.1021/jo00893a007 |

| 10. | Lal, G. S.; Pez, G. P.; Pesaresi, R. J.; Prozonic, F. M.; Cheng, H. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 7048–7054. doi:10.1021/jo990566+ |

| 11. | Lal, G. S.; Lobach, E.; Evans, A. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4830–4832. doi:10.1021/jo000020j |

| 12. | Singh, R. P.; Twamley, B.; Shreeve, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 1918–1924. doi:10.1021/jo016245r |

| 13. | L’Heureux, A.; Beaulieu, F.; Bennett, C.; Bill, D. R.; Clayton, S.; LaFlamme, F.; Mirmehrabi, M.; Tadayon, S.; Tovell, D.; Couturier, M. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3401–3411. doi:10.1021/jo100504x |

| 14. | Umemoto, T.; Singh, R. P.; Xu, Y.; Saito, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18199–18205. doi:10.1021/ja106343h |

| 6. | Nakano, T.; Makino, M.; Morizawa, Y.; Matsumura, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1996, 35, 1019–1021. doi:10.1002/anie.199610191 |

| 7. | Chang, C.-S.; Negishi, M.; Nakano, T.; Morizawa, Y.; Matsumura, Y.; Ichikawa, A. Prostaglandins 1997, 53, 83–90. doi:10.1016/s0090-6980(97)00003-8 |

| 8. | Matsumura, Y.; Nakano, T.; Asai, T.; Morizawa, Y. Synthesis and Properties of Novel Fluoroprostacyclins. In Biomedical Frontiers of Fluorine Chemistry; Ojima, I.; McCarthy, J. R.; Welch, J. T., Eds.; ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 639; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp 83–94. doi:10.1021/bk-1996-0639.ch006 |

| 45. | Gerus, I. I.; Kolycheva, M. T.; Yagupol’skii, Y. L.; Kukhar, V. P. Zh. Org. Khim. 1989, 25, 2020–2021. |

| 5. | Kohl, B.; Sturm, E.; Senn-Bilfinger, J.; Simon, W. A.; Krüger, U.; Schaefer, H.; Rainer, G.; Figala, V.; Klemm, K. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35, 1049–1057. doi:10.1021/jm00084a010 |

| 32. | Tarrant, P.; Brown, H. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 5831–5833. doi:10.1021/ja01156a111 |

| 33. | Li, X.; Pan, H.; Jiang, X. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 4937–4940. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)91263-8 |

| 45. | Gerus, I. I.; Kolycheva, M. T.; Yagupol’skii, Y. L.; Kukhar, V. P. Zh. Org. Khim. 1989, 25, 2020–2021. |

| 39. | Hiraoka, Y.; Kawasaki-Takasuka, T.; Morizawa, Y.; Yamazaki, T. J. Fluorine Chem. 2015, 179, 71–76. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2015.05.006 |

| 40. | Dai, K.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.-G.; Liu, Z.-W.; Lu, J.; Liu, Z.-T. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4721–4728. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00396 |

| 42. | Nishihara, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Maruyama, N.; Sato, K.; Omote, M.; Ando, A.; Kumadaki, I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2003, 122, 247–249. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(03)00053-8 |

| 43. | Ando, A.; Takahashi, J.; Nakamura, Y.; Maruyama, N.; Nishihara, M.; Fukushima, K.; Moronaga, J.; Inoue, M.; Sato, K.; Omote, M.; Kumadaki, I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2003, 123, 283–285. doi:10.1016/s0022-1139(03)00148-9 |

| 35. | Zafrani, Y.; Sod-Moriah, G.; Segall, Y. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 5278–5283. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.04.082 |

| 36. | Fuchibe, K.; Koseki, Y.; Sasagawa, H.; Ichikawa, J. Chem. Lett. 2011, 40, 1189–1191. doi:10.1246/cl.2011.1189 |

| 37. | Sasada, Y.; Shimada, T.; Ushioda, M.; Matsui, S. Liq. Cryst. 2007, 34, 569–576. doi:10.1080/02678290701284279 |

| 38. | Tanaka, H.; Endou, H. Liquid crystal compound, liquid crystal composition and liquid crystal display element. Japanese Patent JPWO2014/129268, Aug 28, 2014. |

| 44. | Ichikawa, J.; Kaneko, M.; Yokota, M.; Itonaga, M.; Yokoyama, T. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3167–3170. doi:10.1021/ol060912r |

| 32. | Tarrant, P.; Brown, H. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 5831–5833. doi:10.1021/ja01156a111 |

| 33. | Li, X.; Pan, H.; Jiang, X. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 4937–4940. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(01)91263-8 |

| 34. | Ohashi, M.; Adachi, T.; Ishida, N.; Kikushima, K.; Ogoshi, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11911–11915. doi:10.1002/anie.201703923 |

| 24. | Saijo, H.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15158–15161. doi:10.1021/ja5093776 |

| 25. | Ohashi, M.; Kawashima, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Kikushima, K.; Ogoshi, S. Organometallics 2015, 34, 1604–1607. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00218 |

| 26. | Ohashi, M.; Shirataki, H.; Kikushima, K.; Ogoshi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6496–6499. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b03587 |

| 27. | Kawashima, T.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17795–17798. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b12007 |

| 28. | Kawashima, T.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17423–17427. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b11671 |

| 29. | Ohashi, M.; Ishida, N.; Ando, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Shigaki, A.; Kikushima, K.; Ogoshi, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 9794–9798. doi:10.1002/chem.201802415 |

| 30. | Shirataki, H.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 1883–1887. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201801721 |

| 31. | Shirataki, H.; Ono, T.; Ohashi, M.; Ogoshi, S. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 851–856. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03674 |

| 41. | Wu, K.; Chen, Q.-Y. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 4077–4084. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(02)00257-0 |

© 2021 Karuo et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the author(s) and source are credited and that individual graphics may be subject to special legal provisions.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms)