Abstract

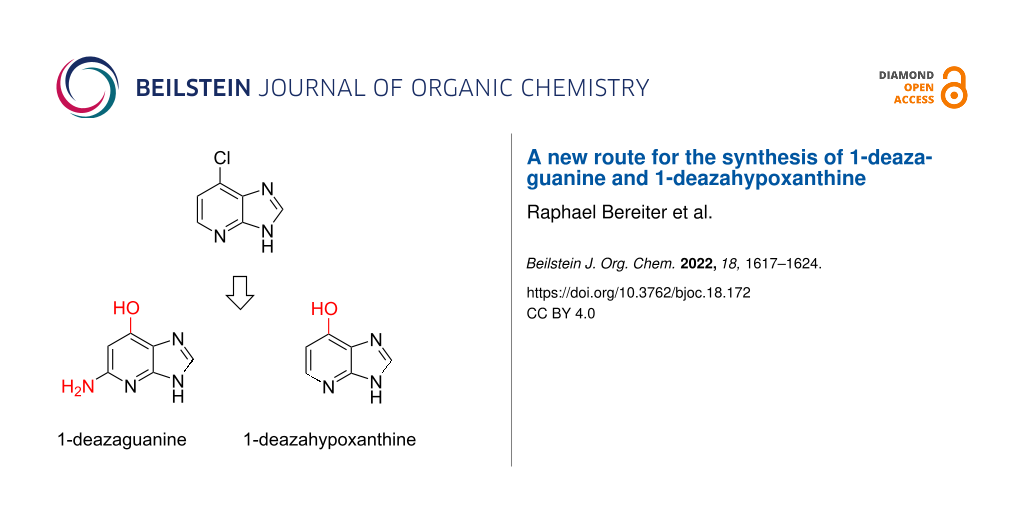

Imidazopyridines and pyrrolopyrimidines are an important class of compounds in medicinal chemistry. They can also be considered as deaza-modified purine nucleobases, and as such have attracted a lot of interest recently in the context of RNA atomic mutagenesis. In particular, for 1-deazaguanine (c1G base), a significant increase in demand is apparent. Synthetic access is challenging and the few reports found in the literature suffer from the requirement of hazardous intermediates and harsh reaction conditions. Here, we report a new six-step synthesis for c1G base, starting from 6-iodo-1-deazapurine. The key transformations are copper catalyzed C–O-bond formation followed by site-specific nitration. A further strength of our route is divergency, additionally enabling the synthesis of 1-deazahypoxanthine (c1I base).

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Deazapurines (imidazopyridines and pyrrolopyrimidines) are N-heterocycles that have become an indispensable part of research in medicinal chemistry [1-3]. Especially, derivatives of 3-deazaguanine (imidazo[4,5-c]pyridines) [4], 7-deazaguanine/-hypoxanthine (pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines) [5,6], and 9-deazaguanine/-hypoxanthine (pyrrolo[3,2-d]-pyrimidines) [7-9] have been in the center of attention and were found to be effective compounds for the inhibition of various molecular targets associated with dysfunction of the central nervous system (e.g., as GABA and serotonin receptor modulators, or as inhibitors of phosphodiesterase PDE10A, glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3), leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase-1A (DYRK1A) and CDC2-like kinase 1 (CLK1), and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) [4]). Similar properties were ascertained for 1-deazapurine derivatives (imidazo[4,5-b]pyridines) and nucleosides thereof [10-12], mostly associated with the inhibition of adenosine deaminase (ADA) [11] and as adenosine receptor antagonists [10]. Another important field of applications for deaza-modified nucleobases is their use in atom-specific mutagenesis experiments. For example, site specific 1-, 3-, and 7-deazapurine mutations of RNA have been fundamental to shed light on their structure, catalysis, and function [13-15]. However, difficulties in these fields arise from the lack of efficient synthetic protocols for various deaza-nucleosides and nucleobases. This is particularly true for the synthesis of 1-deazaguanine and 1-deazahypoxanthine. Previously published routes toward these compounds focused on ring closure of the imidazole part of the purine system after the pyrimidine core had been functionalized, however, the drawback of this approach is the passage of rather hazardous/explosive intermediates. Here, we present a new tactic for the syntheses of 1-deazaguanine and 1-deazahypoxanthine stimulated by a recently published route of our research group for the corresponding nucleosides [16,17], employing the same key reaction, namely the copper-catalyzed coupling of an aryl iodide with benzyl alcohol. We build on a commercially available imidazopyridine derivative and conceived a protecting group strategy to enhance solubility and selectivity to orchestrate the installation of the exocyclic amino and hydroxy groups.

Results and Discussion

1-Deazaguanine

Previously described syntheses for 1-deazaguanine

In 1956, Markees and Kidder reported the first access to 1-deazaguanine [18], followed by a comparable approach one year later by Gorton and Shive [19]. Both started with the conversion of diethyl chelidamate 1 to its dicarbamate analogue 4 (Scheme 1) and further accomplished their syntheses through different formations of the 1-deazapurine heterocycle. The syntheses of the diethyl 2,6-pyridinedicarbamate precursors via Curtius rearrangement, however, involved explosive chelidamyl diazide intermediates 3 (Scheme 1) [18,19].

Scheme 1: Syntheses of C4-substituted diethyl 2,6-pyridinedicarbamates 4, passing hazardous and explosive diacylazide intermediates 3 that are required for Curtius rearrangement in the final step [19].

Scheme 1: Syntheses of C4-substituted diethyl 2,6-pyridinedicarbamates 4, passing hazardous and explosive dia...

Markees and Kidder used an ethyl protection for the O6 and described two options for the generation of 4-ethoxy-2,3,6-triaminopyridine (9). One possibility comprised the deprotection of the dicarbamate 5 with potassium hydroxide giving the diamine 6, followed by azo coupling with the diazonium salt obtained from aniline and sodium nitrite to give azo compound 7. Subsequent reduction with sodium dithionite then afforded triamine 9. Another way comprised the installation of a nitroso group in compound 6 through reaction with in situ-generated nitrous acid giving nitroso compound 8. The subsequent reduction to the corresponding amine with hydrogen sulfide afforded the desired triamine 9. After cyclization of the resulting 4-ethoxy-2,3,6-triaminopyridine (9) with formic acid leading to ethyl-protected compound 10 and liberation of the O6 with hydrogen bromide, 1-deazaguanine (11) was formed in 2 to 4% overall yield (Scheme 2) [18].

Scheme 2: Synthesis of 1-deazaguanine (11) described by Markees and Kidder in 1956 [18].

Scheme 2: Synthesis of 1-deazaguanine (11) described by Markees and Kidder in 1956 [18].

The approach by Gorton and Shive differed from the above path by leaving the hydroxy group of all intermediate 4-hydroxypyridine derivatives 12–15 unprotected [19]. Moreover, instead of azo coupling or nitroso formation, a simple nitration protocol with nitric acid to give the nitro derivative 13 and subsequent reduction with Raney nickel was carried out to obtain the desired 4-hydroxy-2,3,6-triaminopyridine (15) in unspecified yield (Scheme 3). This approach was optimized in 1975 by Schelling and Salemink using benzyl ether protection of the O4 during the imidazopyridine formation to increase the overall yield up to 37% [20]. The last attempt to refine the synthesis of Gorton and Shive, was described by Temple and co-workers in 1976 by their preparation of 1-deaza-6-thioguanine analogues with 28% overall yield [21].

Scheme 3: Synthesis of 1-deazaguanine (11) described by Gorton and Shive in 1957 [19].

Scheme 3: Synthesis of 1-deazaguanine (11) described by Gorton and Shive in 1957 [19].

Synthesis of 1-deazaguanine

Our route to 1-deazaguanine 11 started from 6-iodo-1-deazapurine (16) (Scheme 4), which can be easily prepared from its commercially available 6-chloro derivative [16]. To enable C–O coupling with benzyl alcohol, protection of the N9 with a tetrahydropyranyl group was necessary due to limited solubility of the aryl iodide. Therefore, 6-iodo-1-deazapurine was treated with tosylic acid and 3,4-dihydropyran in dimethylformamide to obtain the corresponding tetrahydropyranyl-protected amine 17. Subsequently, a copper-catalyzed C–O bond formation at C6 using benzyl alcohol in the presence of caesium carbonate, copper(I) iodide, and 1,10-phenanthroline furnished benzyl ether 18 in excellent yields [22]. The switch from 2-tetrahydropyranyl to tert-butyloxycarbonyl protected compound 19 was required for an efficient installation of the exocyclic amine via regioselective nitration in the presence of trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA) and tetrabutylammonium nitrate (TBAN) to give a mixture of the tert-butyloxycarbonyl-protected and deprotected 2-nitro-intermediates 20 and 21, respectively [23-25]. The nitro group was then selectively reduced using trichlorosilane and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) to form benzyl-protected 1-deazaguanine 22 [26]. Finally, the O6-benzyl moiety was cleaved under Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenation to provide 1-deazaguanine (11) in six steps and 6% overall yield. A total of 120 mg of 11 were obtained in the course of this study. At this point, we note that N9-tert-butyloxycarbonyl-protected 6-iodo-1-deazapurine was successfully synthesized but not stable during the cross coupling reaction. We also mention that we did not decide for a direct transformation [27,28] of 6-iodo-1-deazapurine into 6-hydroxy-1-deazapurine for reasons of solubility and desired regioselectivity of the subsequent nitration reaction.

Scheme 4: Six-step synthesis of 1-deazaguanine (11). Abbreviations: p-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH), 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP), trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA), tetrabutylammonium nitrate (TBAN), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA).

Scheme 4: Six-step synthesis of 1-deazaguanine (11). Abbreviations: p-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH), 4-(dimethy...

1-Deazahypoxanthine

Synthesis of 1-deazahypoxanthine

To the best of our knowledge, only one synthesis of 1-deazahypoxanthine has been described so far [29]. Kubo and Hirao started their synthesis from 2,3-diaminopyridine (23) which was converted into benzyl-protected 1-deazaadenine 28 (as a mixture of N7 and N9 regioisomers) in five steps, followed by the introduction of a hydroxy group at C6 under Sandmeyer conditions to give 29 (Scheme 5). To remove the benzyl group, Pearlman’s catalyst in the presence of hydrogen was applied to provide 1-deazahypoxanthine (30) in seven steps and 24% overall yield.

Scheme 5: 1-Deazahypoxanthine (30) synthesis described by Kubo and Hirao in 2019 [29]. For reason of simplicity only one regioisomer of the N7/N9 benzyl compound mixtures is shown.

Scheme 5: 1-Deazahypoxanthine (30) synthesis described by Kubo and Hirao in 2019 [29]. For reason of simplicity o...

Our new route to 1-deazahypoxanthine (30) starts from the tetrahydropyranyl-protected 6-iodo-1-deazapurine 17 which was converted into the O6-benzyl derivative 31 using the copper-catalyzed C–O-bond formation as described above (Scheme 6). Without purification the crude product was treated with hydrochloric acid in methanol to remove the tetrahydropyranyl protecting group. The final step was then accomplished by hydrogenation of benzyl ether 31 to obtain 1-deazahypoxanthine (30) in 44% overall yield.

Scheme 6: Synthesis of 1-deazahypoxanthine (30).

Scheme 6: Synthesis of 1-deazahypoxanthine (30).

Conclusion

We have developed convenient synthetic routes for 1-deazaguanine (11) and 1-deazahypoxanthine (30). Starting from readily accessible 6-iodo-1-deazapurine [16], the key reactions are copper-catalyzed benzyl ether formation and site-specific nitration. The application of protecting groups was necessary for reasons of solubility and to improve selectivity. The obtained heterocycles may serve as core compound for further structural diversification and applications in medicinal chemistry. They will also be useful for nucleosidation reactions to prepare the corresponding nucleosides in straightforward manner.

Experimental

General. Chemical reagents and solvents were purchased in the highest available quality from commercial suppliers (Merck/Sigma-Aldrich, ABCR, Synthonix) and used without further purification. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Macherey-Nagel Polygram® SIL G/UV254 plates. 0.2 mm Silica gel 60 for column chromatography was purchased from Macherey-Nagel. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker UltrashieldTM 400 MHz Plus or a 700 MHz Avance Neo spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS), referenced to the residual solvent signal (DMSO-d6: 2.50 ppm for 1H and 39.52 ppm for 13C spectra; CDCl3: 7.26 ppm for 1H and 77.16 ppm for 13C spectra). Signal assignments are based on 1H,1H-COSY, 1H,13C-HSQC and 1H,13C-HMBC experiments. High resolution mass spectra were recorded in positive ion mode unless otherwise noted on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Orbitrap.

6-Iodo-9-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)-1-deazapurine (17)

6-Iodo-1-deazapurine (2.89 g, 11.79 mmol), p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (TsOH·H2O, 0.34 g, 1.77 mmol) and 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran (2.98 g, 3.21 mL, 35.38 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL dry N,N-dimethylformamide and stirred overnight for 16 hours at 60 °C. The reaction was quenched by adding ammonia 25% (4 mL) and was stirred for further 5 minutes. The solvent and all volatiles were removed under reduced pressure and the oily residue was dissolved in dichloromethane containing 4% triethylamine. Subsequently, the mixture was washed three times with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to dryness. The crude product was purified via silica gel chromatography using 20 to 50% ethyl acetate in cyclohexane (containing 2% triethylamine) as gradient. Yield: 1.86 g (48%) of compound 17 as a brownish solid. TLC (ethyl acetate/cyclohexane 1:1, 2% NEt3): Rf 0.38; 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 1.58 (m, 2H, H2-C(5)-pyran), 1.75 (m, 1H, H(b)-C(4)-pyran), 1.98 (m, 2H, H(b)-C(3)-pyran & H(a)-C(4)-pyran), 2.31 (m, 1H, H(a)-C(3)-pyran), 3.70 (m, 1H, H(b)-C(6)-pyran), 4.01 (m, 1H, H(a)-C(6)-pyran), 5.76 (q, J = 4.29 Hz, 1H, H-C(2)-pyran), 7.78 (d, J = 5.04 Hz, 1H, H-C(1)), 8.05 (d, J = 5.04 Hz, 1H, H-C(2)), 8.75 (s, 1H, H-C(8)); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 22.46 (H-C(3)-pyran), 24.52 (H-C(4)-pyran), 29.94 (H-C(5)-pyran), 67.73 (H-C(6)-pyran), 81.23 (H-C(2)-pyran), 99.35 (H-C(6)), 127.76 (H-C(1)), 137.84 (H-C(8)), 143.30 (H-C(5)), 144.07 (H-C(4)), 144.23 (H-C(2)); ESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for 330.01; found, 330.01.

6-Benzyloxy-9-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)-1-deazapurine (18)

Compound 17 (1.72 g, 5.23 mmol), copper(I) iodide (CuI, 99.52 mg, 0.52 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (188.35 mg, 1.05 mmol), caesium carbonate (Cs2CO3, 2.38 g, 7.32 mmol) and benzyl alcohol (BnOH, 1.13 g, 1.07 mL, 10.45 mmol) were suspended in 2.62 mL toluene (0.5 mL per 1 mmol compound 17) and stirred for 4 hours at 110 °C under atmospheric conditions. After complete reaction (TLC reaction control), the suspension was allowed to cool to room temperature and the catalyst was filtered through celite and washed with dichloromethane containing 1% triethylamine. The filtrate was concentrated to dryness and the crude product was purified via silica gel chromatography using 20 to 40% ethyl acetate in cyclohexane (containing 1% triethylamine) as gradient. Yield: 1.18 g (73%) of compound 18 as a brownish solid. TLC (cyclohexane/ethyl acetate 1:1): Rf 0.23; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 1.57 (m, 2H, H2-C(5)-pyran), 1.74 (m, 1H, H(b)-C(4)-pyran), 1.95 (m, 2H, H(b)-C(3)-pyran & H(a)-C(4)-pyran), 2.29 (m, 1H, H(a)-C(3)-pyran), 3.69 (m, 1H, H(b)-C(6)-pyran), 4.01 (m, 1H, H(a)-C(6)-pyran), 5.53 (s, 2H, H2C-(benzyl)), 5.76 (d, J = 4.38 Hz, 1H, H-C(2)-pyran), 6.96 (d, J = 5.04 Hz, 1H, H-C(1)), 7.34–7.51 (5H, HC-arom. (benzyl)), 8.21 (d, J = 5.04 Hz, 1H, H-C(2)), 8.50 (s, 1H, H-C(8)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 22.58 (H-C(3)-pyran), 24.57 (H-C(4)-pyran), 30.10 (H-C(5)-pyran), 67.69 (H-C(6)-pyran), 70.51 (H2C-benzyl), 80.77 (H-C(2)-pyran), 103.74 (H-C(1)), 124.73 (H-C(5)), 127.96, 128.14, 128.49 (HC-benzyl), 136.39 (C-quart.-benzyl), 140.79 (H-C(8)), 145.59 (H-C(2)), 148.17 (H-C(4)), 156.27 (H-C(6)); ESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for 310.16; found, 310.16.

6-Benzyloxy-9-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-1-deazapurine (19)

Compound 18 (0.9 g, 2.91 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (20 mL), then 5% hydrochloric acid (5 mL) was added and stirred for 2 hours at 50 °C. After complete deprotection (TLC reaction control!), the solvent and all volatiles were removed under reduced pressure and the crude residue was suspended in dichloromethane (6.5 mL). Afterwards, di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (Boc2O, 888.89 mg, 4.07 mmol), 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP, 35 mg, 0.29 mmol) and triethylamine (NEt3, 589 mg, 811 µL, 5.82 mmol) were added and the clear solution was stirred for one hour at room temperature. The mixture was subsequently quenched with saturated ammonium chloride solution, filtrated and concentrated to dryness. The crude product was purified via silica gel chromatography using 0 to 3 % methanol in dichloromethane as gradient. Yield: 730 mg (77%) of compound 19 as a brownish solid. TLC: (6% methanol in dichloromethane): Rf 0.70; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ 1.69 (s, 9H, C(CH3)3-Boc), 5.51 (s, 2H, H2C-(benzyl)), 6.82 (d, J = 5.70 Hz, 1H, H-C(1)), 7.31–7.49 (5H, HC-arom. (benzyl)), 8.35 (s, 1H, H-C(8)), 8.36 (d, J = 5.70 Hz, 1H, H-C(2)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ 28.14 (C(CH3)3-Boc), 71.60 (H2C-benzyl), 86.18 (C(CH3)3-Boc), 105.44 (H-C(1)), 126.46 (H-C(5)), 127.71, 128.48, 128.81 (HC-benzyl), 135.89 (C-quart.-benzyl), 140.80 (H-C(8)), 146.50 (C=O, Boc), 148.08 (H-C(2) & H-C(4)), 157.22 (H-C(6)). ESIMS (m/z) [M + H]+ calcd for 326.15; found, 326.15.

O6-Benzyl-1-deazaguanine (22)

Nitration: Tetrabutylammonium nitrate (TBAN, 624.64 mg, 2.05 mmol) was dissolved in 6 mL dry dichloromethane under argon atmosphere, then, trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA, 430.88 mg, 285.35 µL, 2.05 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 10 minutes. Meanwhile, compound 19 (445.00 mg, 1.37 mmol) was dissolved in dry dichloromethane (6 mL) and cooled to 0 °C under argon atmosphere. The nitration mixture was transferred with a syringe and added over a period of 10 minutes to the dissolved substrate. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred for 1.5 hours at 0 °C under an argon atmosphere. Afterwards, the reaction was quenched by adding the whole reaction mixture into a separatory funnel containing saturated sodium bicarbonate solution, followed by vigorously shaking (do not use a stopper!). The organic layer was washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate solution and brine and was finally dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated to dryness. The crude product was purified via silica gel chromatography using 0 to 4% methanol in dichloromethane as gradient. Yield: 395 mg of a mixture containing the 2-nitro-compound 20 and 21 (for NMR spectra see Supporting Information File 1). TLC: (5% acetone in toluene): Rf 0.34 (compound 20), Rf 0.05 (compound 21).

Reduction: The mixture from the above procedure was suspended in dry dichloromethane (8 mL) at 0 °C, and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 1.06 g, 1.43 mL, 8.21 mmol) was added. A solution containing dry dichloromethane (4 mL) and trichlorosilane (HSiCl3, 778 mg, 581 µL, 5.74 mmol) was prepared at 0 °C under an argon atmosphere, and then added via syringe to the substrate. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for one hour. Subsequent quenching was achieved by the addition of saturated bicarbonate solution (10 mL) and further stirring for one hour. Afterwards, two spoons of silica were added and the whole suspension was concentrated to dryness and dried under high vacuum until a fine powder remains. The silica adsorbed with the product was loaded onto a short silica column and the product was eluted using 0 to 20% methanol in dichloromethane as gradient. The brownish solid was dissolved in boiling water, filtered and cooled to room temperature to precipitate a white solid. Yield: 110 mg (34%, over two steps) of compound 22 as a white solid. TLC: (15% methanol in dichloromethane): Rf 0.44; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 5.34 (s, 2H, H2C-(benzyl)), 6.10 (s, 1H, H-C(1)), 7.36–7.52 (5H, HC-arom. (benzyl)), 7.93 (s, 1H, H-C(8)); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 71.03 (H2C-benzyl), 88.06 (H-C(1)), 110.84 (H-C(5)), 128.30, 128.38, 128.71 (HC-benzyl), 135.11 (C-quart.-benzyl), 140.84 (H-C(4)), 145.69 (H-C(8)), 155.63 (H-C(2)), 157.47 (H-C(6)); ESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for 241.11; found, 241.11.

1-Deazaguanine (11)

Compound 22 (111 mg, 462 µmol) and palladium on carbon 10% (Pd/C, 180.56 mg) were suspended in H2O/methanol 1:1 (7 mL). A rubber septum was applied and hydrogen gas (balloon with syringe) was bubbled through the solution for 10 minutes. The mixture was stirred under hydrogen atmosphere for further four hours at room temperature. The catalyst was filtered through celite and the filtrate was concentrated to dryness. The crude product was purified via silica gel chromatography using 0 to 25% methanol in dichloromethane as gradient. Yield: After recrystallization from water 48 mg (70%) of compound 11 as a white solid. TLC: (25% methanol in dichloromethane) Rf 0.19; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 5.43 (s, 1H, H-C(1)), 5.76 (b, 2H, NH2), 7.78 (s, 1H, H-C(8)), 11.69 (b, 2H, NH & OH); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 89.87 (H-C(1)), 113.28 (H-C(5)), 139.82 (H-C(8)), 145.69 (H-C(4)), 154.08 (H-C(2)), 162.52 (H-C(6)); ESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for 151.06; found, 151.06.

O6-Benzyl-1-deazahypoxanthine (31)

Compound 17 (500 mg, 1.52 mmol), copper(I) iodide (CuI, 28.93 mg, 152 µmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (54.75 mg, 304 µmol), caesium carbonate (Cs2CO3, 692.93 mg, 2.13 mmol) and benzyl alcohol (BnOH, 328.55 mg, 310 µL, 3.04 mmol) were suspended in 0.76 mL of toluene (0.5 mL per 1 mmol compound 17) and stirred for 4 hours at 110 °C under atmospheric conditions. After complete reaction (TLC reaction control), the suspension was allowed to cool to room temperature and the catalyst was filtered through celite and washed with dichloromethane containing 1% triethylamine. The filtrate was concentrated to dryness and the remaining solid was dissolved in methanol (20 mL) and 5% hydrochloric acid (5 mL). This solution was stirred for two hours at 50 °C and concentrated to dryness. The crude compound was purified via silica gel chromatography using 0 to 10% methanol in dichloromethane as gradient. Yield: 250 mg (73%) of compound 31 as a white solid. TLC: (10% methanol in dichloromethane): Rf 0.44; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 5.62 (s, 2H, H2C-(benzyl)), 5.76 (d, J = 4.38 Hz, 1H, H-C(2)-pyran), 7.39–7.62 (6H, HC-arom. (benzyl) & H-C(1)), 8.63 (d, J = 6.60 Hz, 1H, H-C(2)), 8.91 (s, 1H, H-C(8)); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ 71.89 (H2C-benzyl), 103.56 (H-C(1)), 118.33 (H-C(5)), 128.29, 128.66 (HC-benzyl), 134.85 (C-quart.-benzyl), 140.65 (H-C(2)), 145.81 (H-C(8)), 148.62 (H-C(4)), 157.10 (H-C(6)); ESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for 226.10; found, 226.10.

1-Deazahypoxanthine (30)

Compound 31 (230 mg, 1.02 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (15 mL), then palladium on charcoal 10% (Pd/C, 400 mg, 337 µmol) was added and hydrogen (balloon with syringe and septum) was bubbled through the suspension for 10 minutes. Subsequently, the mixture was vigorously stirred under hydrogen atmosphere for 4 hours at room temperature. Afterwards, the suspension was filtered through celite, and the filtrate was concentrated to dryness. The remaining crude product was purified by recrystallization in water. Yield: 83 mg (60%) of compound 30 as a white solid. 1H NMR (700 MHz, DMSO-d6 + 40 µL 5% HCl, 25 °C) δ 6.96 (d, J = 6.83 Hz, 1H, H-C(1)), 8.26 (d, J = 6.83 Hz, 1H, H-C(2)), 8.58 (s, 1H, H-C(8)); 13C NMR (175 MHz, DMSO-d6 + 40 µL 5% HCl, 25 °C) δ 107.00 (H-C(1)), 118.88 (H-C(5)), 137.87 (H-C(2)), 145.78 (H-C(8)), 149.08 (H-C(4)), 160.86 (H-C(6)); ESIMS (m/z): [M − H]− calcd for 134.04; found, 134.03.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: NMR spectra of compounds 17 to 22, 11, 31 and 30. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.7 MB | Download |

References

-

Vanda, D.; Zajdel, P.; Soural, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111569. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111569

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Azam, M. A.; Thathan, J.; Jubie, S. Bioorg. Chem. 2015, 62, 41–63. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2015.07.004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

De Coen, L. M.; Heugebaert, T. S. A.; García, D.; Stevens, C. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 80–139. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00483

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Revankar, G. R.; Gupta, P. K.; Adams, A. D.; Dalley, N. K.; McKernan, P. A.; Cook, P. D.; Canonico, P. G.; Robins, R. K. J. Med. Chem. 1984, 27, 1389–1396. doi:10.1021/jm00377a002

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Scott, R.; Karki, M.; Reisenauer, M. R.; Rodrigues, R.; Dasari, R.; Smith, W. R.; Pelly, S. C.; van Otterlo, W. A. L.; Shuster, C. B.; Rogelj, S.; Magedov, I. V.; Frolova, L. V.; Kornienko, A. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 1428–1435. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201300532

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gibson, C. L.; La Rosa, S.; Ohta, K.; Boyle, P. H.; Leurquin, F.; Lemaçon, A.; Suckling, C. J. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 943–959. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2003.11.030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kaiser, M. M.; Baszczyňski, O.; Hocková, D.; Poštová-Slavětínská, L.; Dračínský, M.; Keough, D. T.; Guddat, L. W.; Janeba, Z. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 1133–1141. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201700293

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Montgomery, J. A.; Niwas, S.; Rose, J. D.; Secrist, J. A., III; Babu, Y. S.; Bugg, C. E.; Erion, M. D.; Guida, W. C.; Ealick, S. E. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 55–69. doi:10.1021/jm00053a008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stipković Babić, M.; Makuc, D.; Plavec, J.; Martinović, T.; Kraljević Pavelić, S.; Pavelić, K.; Snoeck, R.; Andrei, G.; Schols, D.; Wittine, K.; Mintas, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 102, 288–302. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.08.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chang, L. C. W.; von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel, J. K.; Mulder-Krieger, T.; Westerhout, J.; Spangenberg, T.; Brussee, J.; IJzerman, A. P. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 828–834. doi:10.1021/jm0607956

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Cristalli, G.; Vittori, S.; Eleuteri, A.; Grifantini, M.; Volpini, R.; Lupidi, G.; Capolongo, L.; Pesenti, E. J. Med. Chem. 1991, 34, 2226–2230. doi:10.1021/jm00111a044

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Iaroshenko, V. O.; Ostrovskyi, D.; Petrosyan, A.; Mkrtchyan, S.; Villinger, A.; Langer, P. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2899–2903. doi:10.1021/jo102579g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Neuner, S.; Falschlunger, C.; Fuchs, E.; Himmelstoss, M.; Ren, A.; Patel, D. J.; Micura, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15954–15958. doi:10.1002/anie.201708679

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Polacek, N. Chimia 2013, 67, 322–326. doi:10.2533/chimia.2013.322

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Seela, F.; Debelak, H.; Usman, N.; Burgin, A.; Beigelman, L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 1010–1018. doi:10.1093/nar/26.4.1010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bereiter, R.; Renard, E.; Breuker, K.; Kreutz, C.; Ennifar, E.; Micura, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10344–10352. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c01877

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Egger, M.; Bereiter, R.; Mair, S.; Micura, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202207590. doi:10.1002/anie.202207590

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Markees, D. G.; Kidder, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 4130–4135. doi:10.1021/ja01597a074

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Gorton, B. S.; Shive, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 670–672. doi:10.1021/ja01560a044

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Schelling, J. E.; Salemink, C. A. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1974, 93, 160–162. doi:10.1002/recl.19740930607

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Temple, C., Jr.; Smith, B. H.; Kussner, C. L.; Montgomery, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 3784–3788. doi:10.1021/jo00886a003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wolter, M.; Nordmann, G.; Job, G. E.; Buchwald, S. L. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 973–976. doi:10.1021/ol025548k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deghati, P. Y. F.; Wanner, M. J.; Koomen, G.-J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 1291–1295. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(99)02271-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deghati, P. Y. F.; Bieräugel, H.; Wanner, M. J.; Koomen, G.-J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 569–573. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(99)02073-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wanner, M. J.; Rodenko, B.; Koch, M.; Koomen, G. J. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2004, 23, 1313–1320. doi:10.1081/ncn-200027566

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Orlandi, M.; Tosi, F.; Bonsignore, M.; Benaglia, M. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3941–3943. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01698

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Cheon, H.-S.; Chae, J. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 5804–5809. doi:10.1021/jo400702z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lembacher-Fadum, C.; Gissing, S.; Pour, G.; Breinbauer, R. Monatsh. Chem. 2021. doi:10.1007/s00706-021-02844-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hirao, Y.; Seo, S.; Kubo, T. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 20928–20935. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b05033

Return to citation in text: [1] [2]

| 16. | Bereiter, R.; Renard, E.; Breuker, K.; Kreutz, C.; Ennifar, E.; Micura, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10344–10352. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c01877 |

| 1. | Vanda, D.; Zajdel, P.; Soural, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111569. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111569 |

| 2. | Azam, M. A.; Thathan, J.; Jubie, S. Bioorg. Chem. 2015, 62, 41–63. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2015.07.004 |

| 3. | De Coen, L. M.; Heugebaert, T. S. A.; García, D.; Stevens, C. V. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 80–139. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00483 |

| 4. | Revankar, G. R.; Gupta, P. K.; Adams, A. D.; Dalley, N. K.; McKernan, P. A.; Cook, P. D.; Canonico, P. G.; Robins, R. K. J. Med. Chem. 1984, 27, 1389–1396. doi:10.1021/jm00377a002 |

| 18. | Markees, D. G.; Kidder, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 4130–4135. doi:10.1021/ja01597a074 |

| 7. | Kaiser, M. M.; Baszczyňski, O.; Hocková, D.; Poštová-Slavětínská, L.; Dračínský, M.; Keough, D. T.; Guddat, L. W.; Janeba, Z. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 1133–1141. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201700293 |

| 8. | Montgomery, J. A.; Niwas, S.; Rose, J. D.; Secrist, J. A., III; Babu, Y. S.; Bugg, C. E.; Erion, M. D.; Guida, W. C.; Ealick, S. E. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 55–69. doi:10.1021/jm00053a008 |

| 9. | Stipković Babić, M.; Makuc, D.; Plavec, J.; Martinović, T.; Kraljević Pavelić, S.; Pavelić, K.; Snoeck, R.; Andrei, G.; Schols, D.; Wittine, K.; Mintas, M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 102, 288–302. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.08.008 |

| 18. | Markees, D. G.; Kidder, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 4130–4135. doi:10.1021/ja01597a074 |

| 5. | Scott, R.; Karki, M.; Reisenauer, M. R.; Rodrigues, R.; Dasari, R.; Smith, W. R.; Pelly, S. C.; van Otterlo, W. A. L.; Shuster, C. B.; Rogelj, S.; Magedov, I. V.; Frolova, L. V.; Kornienko, A. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 1428–1435. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201300532 |

| 6. | Gibson, C. L.; La Rosa, S.; Ohta, K.; Boyle, P. H.; Leurquin, F.; Lemaçon, A.; Suckling, C. J. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 943–959. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2003.11.030 |

| 18. | Markees, D. G.; Kidder, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 4130–4135. doi:10.1021/ja01597a074 |

| 19. | Gorton, B. S.; Shive, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 670–672. doi:10.1021/ja01560a044 |

| 4. | Revankar, G. R.; Gupta, P. K.; Adams, A. D.; Dalley, N. K.; McKernan, P. A.; Cook, P. D.; Canonico, P. G.; Robins, R. K. J. Med. Chem. 1984, 27, 1389–1396. doi:10.1021/jm00377a002 |

| 19. | Gorton, B. S.; Shive, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 670–672. doi:10.1021/ja01560a044 |

| 13. | Neuner, S.; Falschlunger, C.; Fuchs, E.; Himmelstoss, M.; Ren, A.; Patel, D. J.; Micura, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15954–15958. doi:10.1002/anie.201708679 |

| 14. | Polacek, N. Chimia 2013, 67, 322–326. doi:10.2533/chimia.2013.322 |

| 15. | Seela, F.; Debelak, H.; Usman, N.; Burgin, A.; Beigelman, L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 1010–1018. doi:10.1093/nar/26.4.1010 |

| 18. | Markees, D. G.; Kidder, G. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 4130–4135. doi:10.1021/ja01597a074 |

| 10. | Chang, L. C. W.; von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel, J. K.; Mulder-Krieger, T.; Westerhout, J.; Spangenberg, T.; Brussee, J.; IJzerman, A. P. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 828–834. doi:10.1021/jm0607956 |

| 19. | Gorton, B. S.; Shive, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 670–672. doi:10.1021/ja01560a044 |

| 11. | Cristalli, G.; Vittori, S.; Eleuteri, A.; Grifantini, M.; Volpini, R.; Lupidi, G.; Capolongo, L.; Pesenti, E. J. Med. Chem. 1991, 34, 2226–2230. doi:10.1021/jm00111a044 |

| 10. | Chang, L. C. W.; von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel, J. K.; Mulder-Krieger, T.; Westerhout, J.; Spangenberg, T.; Brussee, J.; IJzerman, A. P. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 828–834. doi:10.1021/jm0607956 |

| 11. | Cristalli, G.; Vittori, S.; Eleuteri, A.; Grifantini, M.; Volpini, R.; Lupidi, G.; Capolongo, L.; Pesenti, E. J. Med. Chem. 1991, 34, 2226–2230. doi:10.1021/jm00111a044 |

| 12. | Iaroshenko, V. O.; Ostrovskyi, D.; Petrosyan, A.; Mkrtchyan, S.; Villinger, A.; Langer, P. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2899–2903. doi:10.1021/jo102579g |

| 16. | Bereiter, R.; Renard, E.; Breuker, K.; Kreutz, C.; Ennifar, E.; Micura, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10344–10352. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c01877 |

| 17. | Egger, M.; Bereiter, R.; Mair, S.; Micura, R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202207590. doi:10.1002/anie.202207590 |

| 21. | Temple, C., Jr.; Smith, B. H.; Kussner, C. L.; Montgomery, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 3784–3788. doi:10.1021/jo00886a003 |

| 19. | Gorton, B. S.; Shive, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 670–672. doi:10.1021/ja01560a044 |

| 20. | Schelling, J. E.; Salemink, C. A. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1974, 93, 160–162. doi:10.1002/recl.19740930607 |

| 29. | Hirao, Y.; Seo, S.; Kubo, T. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 20928–20935. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b05033 |

| 29. | Hirao, Y.; Seo, S.; Kubo, T. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 20928–20935. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b05033 |

| 26. | Orlandi, M.; Tosi, F.; Bonsignore, M.; Benaglia, M. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3941–3943. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01698 |

| 27. | Xiao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Cheon, H.-S.; Chae, J. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 5804–5809. doi:10.1021/jo400702z |

| 28. | Lembacher-Fadum, C.; Gissing, S.; Pour, G.; Breinbauer, R. Monatsh. Chem. 2021. doi:10.1007/s00706-021-02844-1 |

| 22. | Wolter, M.; Nordmann, G.; Job, G. E.; Buchwald, S. L. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 973–976. doi:10.1021/ol025548k |

| 23. | Deghati, P. Y. F.; Wanner, M. J.; Koomen, G.-J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 1291–1295. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(99)02271-6 |

| 24. | Deghati, P. Y. F.; Bieräugel, H.; Wanner, M. J.; Koomen, G.-J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 569–573. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(99)02073-0 |

| 25. | Wanner, M. J.; Rodenko, B.; Koch, M.; Koomen, G. J. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2004, 23, 1313–1320. doi:10.1081/ncn-200027566 |

| 19. | Gorton, B. S.; Shive, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 670–672. doi:10.1021/ja01560a044 |

| 16. | Bereiter, R.; Renard, E.; Breuker, K.; Kreutz, C.; Ennifar, E.; Micura, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10344–10352. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c01877 |

© 2022 Bereiter et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.