Abstract

In this paper, the behavior of a bicolor fluorescent indicator for the detection of barium cations formed by double-beta decay of 136Xe is analyzed by means of computational tools. Both DFT and TDDFT permit to understand the origin of the bicolor fluorescent signal emitted by 1-arylbenzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizines in the free and Ba2+-bound states. The aromatic character of the fluorophore is analyzed by means of energetic (hyperhomodesmotic equations), structural (harmonic oscillator model of aromaticity, HOMA) and magnetic (nucleus independent chemical shifts, NICS) criteria. It is concluded that the aromatic character of the fluorophore is better described as the combination of two aromatic subunits integrated in the polycyclic system. Different DFT functional are used to analyze the photochemical behavior of this family of sensors. It is concluded that PBE0 and M06 functionals describe better the excitation process in the free state, whereas interaction of the sensor with Ba2+ requires the M06L functional. TDDFT analysis of the emission spectra shows larger errors, which have been corrected by means of a structural model. The bicolor behavior is rationalized based on the decoupling between the para-phenylene and benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine components that results in a blue shift upon Ba2+ coordination.

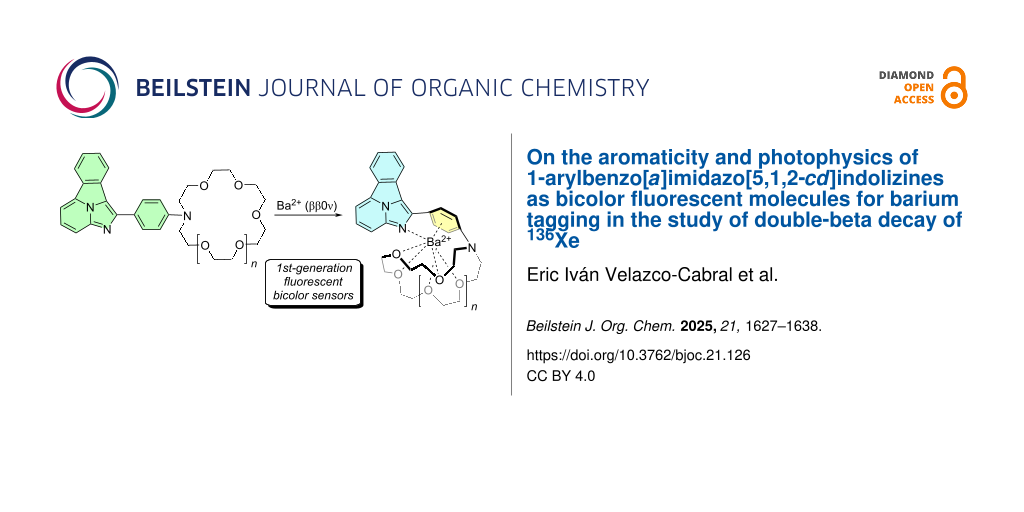

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Double beta-decay [1] is a radioactive decay in which two neutrons are converted into two protons by means of the transformation of two quarks down into two quarks up (Figure 1). This process involves the emission of two W− bosons that in turn evolve towards the emission of two electrons. In the two-neutrino double-beta decay (ββ2ν), two electronic antineutrinos are also produced. Another possibility corresponds to the neutrinoless double-beta decay [2] (ββ0ν). This latter process could take place if the electronic neutrino is a Majorana particle [3], namely, it coincides with its own antiparticle (). This would result in a mutual annihilation, according to which the two emitted electrons would take more energy than in the ββ2ν process. In both processes, the initial nuclide must advance two steps beyond the periodic table. Among the possible candidates for double-beta decay, 136Xe is a suitable isotope. In the ββ2ν radioactive decay, the reaction is 136Xe → 136Ba2+ + 2e− + 2

. The ββ0ν analog would consist of simply 136Xe → 136Ba2+ + 2e−. Both transformations are extraordinarily rare events. For instance, the estimated half-life for the ββ0ν decay is at least higher than 2.3·1026 years, whereas the current best estimate of the age of the universe [4] is 13.8·109 years. However, characterization of the neutrino as a Majorana particle constitutes a formidable challenge that would have an extraordinary impact in cosmology since this would contribute decisively to explain why our universe is formed by matter and not antimatter [5].

Figure 1: Two possible double beta decay modes. Left: with emission of two electronic antineutrinos (ββ2ν). Right: neutrinoless double beta decay (ββ0ν).

Figure 1: Two possible double beta decay modes. Left: with emission of two electronic antineutrinos (ββ2ν). R...

Within this context, from a chemical point of view, detection of ββ0ν radioactive decay of 136Xe requires an extremely sensitive detection of 136Ba2+. One promising candidate [6] would be a radiometric fluorescent sensor. With this idea in mind, we started a project aiming at designing, synthetizing and validating a fluorescent indicator that would fulfill the following conditions: (i) high discrimination between the free and Ba2+-bound states; (ii) high binding affinity for Ba2+, and low background signal for the chelated state. We reasoned that a bicolor fluorescent indicator [7] (FBI), namely, a radiometric sensor that emit the fluorescent signal at different wavelengths in the free and bound states, would be the best option given the extremely rare character of the ββ0ν event.

After analyzing different possibilities, we finally observed that FBIs based on benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizines as fluorescent moieties constitute promising candidates to detect Ba2+ cations [8,9] (Figure 2). Another essential component is an aza-crown ether of appropriate dimensions to capture the barium cation. In addition, one para-disubstituted phenyl (or aryl) group is installed to generate selective cation–π interactions. Finally, a spacer (denoted as X and Y in Figure 2) and a linker (denoted as Z) to anchor the sensor to a suitable surface via a covalent interaction are required. Ideally, different configurations and conformations of the fluorophore in the free and chelated states would result in a bicolor behavior in the emission spectra. Indeed, initial experiments were successful. However, we observed that translation of the behavior of these FBIs from supramolecular chemistry to solid–gas interfaces raises important issues in terms of both discrimination between free and chelated states and photophysical properties [10].

Figure 2: General structure of first-generation bicolor fluorescent indicators based on 1-aryl benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizines. X and Y represent the spacer and Z stands for the linker to the surface, respectively. The different emission wavelengths in the free and bound states are highlighted.

Figure 2: General structure of first-generation bicolor fluorescent indicators based on 1-aryl benzo[a]imidaz...

Therefore, in this paper, we reexamine the electronic features of these 1-arylbenzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine-based FBIs in terms of aromaticity (a relevant feature to analyze the nature of the excited states) and emission properties. The final goal of this research has been to contribute to the design of a second generation of bicolor fluorescent indicators for barium tagging in neutrinoless double-beta decay.

Results and Discussion

First, we analyzed the aromaticity of parent benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine 1 (Scheme 1) in order to get a better understanding of the properties of this tetracyclic system [11]. Since ground state aromaticity can be assessed by energetic [12], geometric [13] and magnetic [14,15] criteria, among others [16-18], we analyzed first the resonance energy of 1 with respect to the aromatic resonance energies of the ortho-phenyl and the bicyclic imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine components. In reaction A, an hyperhomodesmotic equation [19] 2 + 3 → 4 + 1 was defined, in which the conjugation of the bicyclic imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine unit was removed, while preserving the ortho-disubstituted phenyl ring, highlighted in yellow in Scheme 1A. This reaction yielded a stabilization energy of ca. 17 kcal/mol. In the alternative hyperhomodesmotic reaction B, defined as 5 + 6 → 7 + 1, the formal ten-electron Hückel aromaticity of the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine moiety (in blue) was preserved while the phenyl component was decomposed. The computed stabilization energy of this second reaction was calculated to be of 28 kcal/mol, slightly lower than the aromatic stabilization energy (ASE) and isomerization stabilization energy (ISE) calculated for benzene [20] (see reaction D in Scheme 1). Most likely this lowering stems from the strain imposed to the ortho-phenylene moiety in the tetracyclic structure. Combination of reactions A and B in the form

yields an average value of ⟨ΔEAB⟩ = −22.6 kcal/mol. A similar treatment of the separate components as outlined in reactions C and D shows a much lower stabilization energy for imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine 8 and a higher stabilization energy of benzene (15). Combination of these latter equations yields

This second averaged equation results in a computed stabilization energy of ⟨ΔECD⟩ = −20.5 kcal/mol, 2.1 kcal/mol lower than that calculated for ⟨ΔEAB⟩. These results indicate that there is a noticeable interplay between the phenyl (yellow) and imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine (blue) components of 1 and that these aromatic units preserve their respective aromatic characters.

Scheme 1: Hyperhomodesmotic equations used to analyze the resonance energy of benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine 1 with respect to the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine unit (A) and the ortho-disubstituted phenyl ring (B). Similar reactions for the separate components of 1 are shown in (C) and (D). All the relative energies have been calculated at the B3LYP-D3BJ/6-311+G** level of theory. Explicit hydrogens on the saturated Csp³ atoms are highlighted in gray.

Scheme 1: Hyperhomodesmotic equations used to analyze the resonance energy of benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indoli...

We next examined the aromatic character of benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine 1 by analyzing its geometry in terms of bond equalization. Three possibilities were considered: a total delocalized geometry denoted as 1a in Figure 3A, a peripheric conjugation 1b that excludes the participation of the lone pair of the central N atom and, finally, a two-component delocalization scheme denoted as 1c. The chief features of fully optimized structures of 1 at the ground state (S0) and first singlet excited state (S1) are reported in Figure 3B. Using geometric criteria, we computed the HOMA [21,22] for 1 at the ground state, according to the following expression:

In this equation, n is the number of covalent bonds, k describes the type of bond (CC or CN), stands for the optimal CC or CN distances associated with aromatic structures,

represents the corresponding bond distance gathered in Figure 3B, and αk is a parametric term defined as

where is the standard single bond distance of the k-pair of atoms (C–C, C–N) and

is the same paremeter but referred to the corresponding double bonds (C=C, C=N).

Figure 3: (A) Total, peripheral and modular delocalization patterns for fluorophore 1. The ground state (So) Harmonic oscillator models of aromaticity, both standard (HOMA) and computational antiaromaticity-including (HOMAc) descriptors are gathered for each pattern. Descriptor n stands for the number of covalent bonds, of each pattern, according to Equation 1. (B) Anisotropy of the current induced density (ACID) diagram of compound 1. (isosurface value: 0.035 a.u.) (C) Bond distances (in Å) for fully optimized structure of 1, computed at the ground state (S0) and at the first singlet excited state (S1, in orange). Results obtained at the B3LYP-D3BJ/6-311+G** (S0) and using TDDFT (S1). Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Figure 3: (A) Total, peripheral and modular delocalization patterns for fluorophore 1. The ground state (So) ...

We computed the HOMA values associated with the total, peripheral and modular patterns using the standard parameters and a more recent set based on computational parameters that take into account antiaromaticity, denoted as HOMAc [23]. According to our results, formal structure 1a is the less aromatic one, a result compatible with the formal anti-Hückel character of this structure, with 16 π-electrons if the central nitrogen atom is included in the electron counting. Peripheral structure 1b is formally Hückel aromatic since the lone pair of this atom is not considered, thus resulting in 14 π-electrons and a higher HOMA value. Finally, modular structure 1c includes formally separated components with six and ten π-electrons, both units being Hückel aromatic. This structure shows the highest HOMA and HOMAc values, which is in agreement with our conclusion from the analysis in terms of stabilization energy. In addition, an analysis of the Anisotropy of the induced current density (ACID) plot [24] calculated for 1 (Figure 3B) shows a significant diatropic ring current formally associated with the peripheral model 1b. Another diatropic contribution can be assigned to the modular model 1c, with a vortex in the bond connecting the phenyl group with the pyrrole ring. Interestingly, paratropic ring currents are observed close to the molecular plane.

This conclusion is reinforced by the NICS computed for the four rings of 1. As shown in Table 1, the isotropic NICS values at the molecular plane are always negative, but the pyrrole ring shows the lowest value. Indeed, if the NICSzz(0) values are considered, a paratropic character is observed at the center of the pyrrole and imidazole rings. The situation is more consistent when the NICS values are computed 1 Å above the molecular plane [25,26] since diatropic ring currents are observed over the centers of the four ring points of electron density. However, the issues associated with magnetic criteria to describe the aromaticity of polycyclic systems must be taken into account. Thus, a recent study [27] emphasizes the relative (and competitive) contributions of global, semi-local and local ring currents associated with Kekulé resonance and Clar’s disjoint aromatic π–sextets, which reveals different coexisting ring current circuits in this kind of systems. Therefore, the assessment of the aromaticity of system 1 relies on the combined agreement among conceptually different criteria. In summary, thermochemical, structural and magnetic analysis permit to conclude that the aromaticity of the fluorophore defined by 1 has modular and peripheral character, which results in a moderate total aromaticity for this parent compound in the ground state. Since it is known that the aromaticity rules are reversed in 1ππ* excited states [28], the high fluorescent response of 1 is connected with its higher aromaticity at the excited S1 state. Actually, the two peripheric C–C bonds of the central pyrrole ring are slightly shorter in the optimized S1 state, thus suggesting a less modular aromatic character. Unfortunately, since the HOMA parameters for excited states [29] are available for triplet 3ππ* states only and we are interested in fluorescence emission spectra, this kind of quantitative assessment of aromaticity was not possible.

Table 1: NICS(iso) and NICSzz values at the molecular plane (z = 0) and 1 Å (z = 1) above this plane in a perpendicular direction. Points a–c correspond to the respective ring points, in light red. Perpendicular points at z = 1 are shown in light green.

![[Graphic 9]](/bjoc/content/inline/1860-5397-21-126-i19.png?max-width=637&scale=1.0)

|

||||

| Point | NICS(iso)a | NICSzza | ||

| z = 0 | z = 1 | z = 0 | z = 1 | |

| a | −11.729 | −16.728 | −11.798 | −32.255 |

| b | −12.486 | −11.486 | +8.812 | −31.343 |

| c | −8.740 | −10.298 | −12.648 | −27.974 |

| d | −7.287 | −7.705 | +8.730 | −17.884 |

aValues computed using the B3LYP/6-311+G** hybrid functional and the GIAO method.

The role of the crown ether and the para-phenylene moieties was also analyzed. The interactions of different sized crown ethers with Ba2+ and coordination with the aromatic ring modeled by means of benzene (14, highlighted in yellow in Scheme 2) were studied computationally. Although the efficiency of crown ethers as components in cation-selective fluorescent probes has been extensively explored [7,30], to the best of our knowledge no previous computational DFT studies on the selectivity of crown ethers of different sizes with Ba2+ have been reported. Therefore, we explored (Scheme 2A) the binding between this cation and 12-crown-4 (16a, n = 1), 15-crown-5 (16b, n = 2), 18-crown-6 (16c, n = 3) and 21-crown-7 (16d, n = 4), to form Ba2+·crown ethers 15a–d. We compared the corresponding binding energies by means of the following isodesmic equation:

Where the different terms correspond to Gibbs energies computed at 298.17 K. We also extended this study to the interaction between complexes 15a–d and benzene (14) and computed the corresponding complexation energies as

In addition, Figure 4 includes the chief geometric parameters of the different complexes, as well as the corresponding free energy values.

Scheme 2: Isodesmic (A) and reaction profiles (B) for the analysis of the interaction of Ba2+ with different crown ethers and a benzene ring as a computational model of para-phenylene ring shown in Figure 2.

Scheme 2: Isodesmic (A) and reaction profiles (B) for the analysis of the interaction of Ba2+ with different ...

Figure 4: Fully optimized geometries (B3LYP-D3BJ/6ccrow-311++G**&DefTZVPP(Ba) level of theory) of Ba2+·crown ethers 15a–d (A) and phenyl·Ba2+·crown ether complexes 17a–d (B). Barium cations are represented in dark blue. Descriptors (⟨RBa0⟩)n denote the average Ba–O bond distances (in Å) for the different crown ethers. Distances between Ba2+ and the ring points of electron density of benzene (in green) are also gathered in (B). ΔGiso and ΔGrxn terms stand for the Gibbs energies (in kcal/mol) described in Scheme 2 and have been calculated according to Equation 3 and Equation 4. Numbers in parentheses are the relative ΔGrxn energies with respect to complex 17a. ΔΔGtot energies have been calculated according to Equation 5. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Figure 4: Fully optimized geometries (B3LYP-D3BJ/6ccrow-311++G**&DefTZVPP(Ba) level of theory) of Ba2+·crown ...

Our calculations show that, as expected, 12-crown-4 16a and 15-crown-5 16b are too small and consequently the barium cation lies outside the average molecular plane determined by the macrocycle. In the case of 18-crown-6 16c, the cyclic ligand accommodates very well the cation, which is now within the average molecular plane. In addition, the corresponding ΔGiso values increase with the n-values (Figure 4A). Ligand 21-crown-7 15d suggests that this size of the cyclic ligand is less than optimal, since the calculated structure shown a concave-convex topology, in which one oxygen atom, highlighted by an asterisk, lies out from the direct coordination perimeter, thus suggesting that this ligand is too big. The relatively lower increase of the ΔGiso(d) with respect to its ΔGiso(c) congener also indicate that the stabilization induced by the additional oxygen atom is lower in magnitude.

An analysis of the effect of the aromatic ring represented by the benzene ring shown in Scheme 2 and in Figure 4B was also performed. We observed that for complexes 17a (n = 1) and 17b (n = 2) the low size of the crown ethers generates a poor coordination to Ba2+, which results in more charge available for further coordination thus giving rise to a relatively strong π–cation interaction with the phenyl group. In the case of complex 17c (n = 3) stemming from 18-crown-6, the barium cation remains within the average molecular plane determined by the macrocyclic moiety. The larger ΔGiso value for 15c results in a relatively lower ΔGrxn free energy for 17c, given the lower charge available for further interaction with the phenyl group. The geometry of complex 17d (n = 4) resembles that found for parent 15d, since the 21-crown-7 moiety adopts a concave–convex shape, in which the barium cation occupies a central position within the concave face. Also in this case, one oxygen atom of the oversized macrocycle does not interact directly with Ba2+, thus resulting in a non-optimal coordination pattern. Therefore, the shape of the ligand and the low positive charge available for the cation result in the largest Ba2+-ring point distance and in a positive value of ΔGrxn(d) although the corresponding energy is slightly negative (ca. −4 kcal/mol). If we combine both relative magnitudes in the form

in which the second term of the right hand (in brackets) correspond to the relative Gibbs reaction energy with respect to 17a, gathered in parentheses in Figure 4. These combined ΔΔGtot values permit to conclude that 18-crown-6 (n = 3) is the best tradeoff between coordination to the cation and subsequent interaction with the phenyl group. This is the reason why in our design we introduced and aza-equivalent of 18-crown-6, namely the 1,4,7,10,13-pentaoxa-16-azacyclooctadecane moiety.

We next investigated the coupling between the two components of the sensor gathered in Figure 2 at the free and Ba2+-bound states, namely the aza-crown ether-Ba2+-para-phenylene and the benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine components. We chose compound 18 (Figure 5) as a convenient computational model. We calculated the energy profile associated with the rotation between the 1,4-phenylene and benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine 1 components, defined as variation of the ω = a–d–c–d dihedral angle shown in Figure 5. Our calculations show that, in the absence of barium, compound 18 exhibits almost coplanar components, so both systems form a combined fluorophore highlighted in green in Figure 5. The correlation between energy and this dihedral angle by means of a Karplus-like [31] equation up to the fourth degree in the form

shows an excellent correlation (R2 = 0.9987). The situation is completely different in the presence of a naked barium cation (Figure 5B). Thus, the E(ω) – E(0) vs ω curve shows a wide minimum in the region of 90 deg. Also in this case, the correlation for a fourth-degree polynomial expansion in terms of cosnω in the form

with a correlation factor of R2 = 0.9829. This minimum involves the simultaneous coordination of the cation to one nitrogen atom of the fluorophore 1, to the para-phenylene group and the crown ether, a result in line with our experimental results [8].

Figure 5: Relaxed scan of the relative conformational energies of sensor 18 at the free state (A) and bound to barium cation 18·Ba2+ (B), calculated at the B3LYP-D3BJ/6-31G*&DefTZVPP(Ba) level of theory. Capture of one naked barium cation generated after a neutrinoless double-beta decay (ββ0ν) is assumed. The dihedral angle ω = a–b–c–d formed by the two components of the fluorophore are graphically defined.

Figure 5: Relaxed scan of the relative conformational energies of sensor 18 at the free state (A) and bound t...

Next, we analyzed the geometry and electronic features of synthetic compounds 18 and 18·Ba2+ as a model case study of the general design shown in Figure 2. Instead of the isolated cation generated by the ββ0ν process, we included barium perchlorate since this salt was used in experimental studies, as it can be observed in Scheme 3. DFT and TDDFT calculations show that the geometries of 18 at the ground first excited states are quite similar (Figure 6), the aza-crown ether component being more flexible, in good agreement with our experimental observations [9], with very low values of the dihedral angle formed by the benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine and the para-phenylene groups, especially in the S1 state, thus indicating that both aromatic units are coupled under excitation–relaxation to produce the corresponding absorption–emission spectra (vide infra). The calculated structures of 18 complexed with barium perchlorate are more rigid, with only small modifications on going from the ground state to the first single excited state (Figure 6). However, the presence of the two perchlorate anions results in additional coordination with Ba2+, thus resulting in larger values of the Ba–N distances, as well as of the average Ba–O and Ba–phenylene distances. In addition, the ω = a–b–c–d dihedral angle between fluorophore 1 and the 1,4-phenylene ring is smaller than that calculated for the naked barium cation, but still shows a noticeable departure from coplanarity.

Scheme 3: Reaction of fluorescent probe 18 with barium perchlorate, as indicated in Figure 2 (X = O, Y, Z = Me). The possible coordination patterns are shown.

Scheme 3: Reaction of fluorescent probe 18 with barium perchlorate, as indicated in Figure 2 (X = O, Y, Z = Me). The ...

![[1860-5397-21-126-6]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-126-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Fully optimized structures (B3LYP-D3BJ/6-311++G(d,p)&DefTZVPP(Ba) level of theory) of compounds 18 and 18·Ba2+ at the ground (S0, carbon atoms in gray) and first excited (S1, carbons in orange) sates. Bond distances are given in Å. The dihedral angles ω = a–b–c–d, in absolute value, are reported in deg.

Figure 6: Fully optimized structures (B3LYP-D3BJ/6-311++G(d,p)&DefTZVPP(Ba) level of theory) of compounds 18 ...

The peculiar behavior of barium perchlorate with respect to naked Ba2+ prompted us to compare the photophysical properties of unbound compound 18 in the presence of Ba(ClO4)2. The values corresponding to the adiabatic absorption (S0(optimized) → S1*, adiabatic absorption) and emission (S1(optimized) → S0, fluorescence) are reported in Table 2, together with the differences between the free and bound states. The corresponding signed errors are gathered in Figure 7.

Table 2: Calculateda absorption (λabs, in nm) and emission (λem, in nm) wavelengths of compound 19 at the free and barium perchlorate bound states, using different DFT functionals.

| Functional | λabs | λem | |||||

| 18 | 18·Ba(ClO4)2 | Δλabsb | 18 | 18·Ba(ClO4)2 | Δλemb | ||

| experimentalc | 434 | 420 | −14 | 508 | 434 | −74 | |

| BHandH | 377 | 335 | −42 | 425 | 364 | −61 | |

| BHandHLYP | 376 | 335 | −41 | 427 | 376 | −51 | |

| B3LYP | 462 | 397 | −36 | 462 | 426 | −36 | |

| CAM-B3LYP | 382 | 342 | −40 | 435 | 375 | −60 | |

| M06 | 431 | 382 | −49 | 478 | 420 | −58 | |

| M06-L | 384 | 341 | −43 | 621 | 645 | +24 | |

| M06-2X | 518 | 432 | −86 | 445 | 379 | −66 | |

| PBE | 433 | 369 | −64 | 473 | 457 | −16 | |

| ωB97XD | 377 | 340 | −37 | 434 | 372 | −62 | |

aCalculations performed with the 6-311++G(d,p)& DefTZVPP (Ba) basis sets and effective-core potential. bDifference between the free and chelated values: Δλ = λ(19·Ba(ClO4)2) − λ(19). cData taken from ref. [8].

Figure 7: Comparison between the calculated and experimental differences between the emission wavelength of 18 and 18·Ba(ClO4)2, with different functionals within DFT and TDDFT frameworks.

Figure 7: Comparison between the calculated and experimental differences between the emission wavelength of 18...

The behavior of the different functionals resulted to be very variable, although the ground state and excited state geometries were very similar. In the case of absorption wavelengths, wB97XD, BHandHHLYP and CAM-B3LYP were the most convenient functionals to describe the blue shift on going from the free to the Ba-chelated state. If errors for the free and chelated states are considered, B3LYP and ωB97XD are the functionals that introduce the lowest error values, although these data are less relevant than Δλabs.

Calculated emission wavelengths and the differences between the calculated fluorescent emissions in the free and bound states showed in some cases noticeable differences. Thus, M06-L and wB97XD functionals described better the emission of 18 at the unbound state, whereas M06 and M06-L gave the lower errors for the λem values of 18·Ba(ClO4)2. However, the situation was found to be different when the Δλem values were calculated. In this case, M06 (which even predicted a red shift) and PBE were the less accurate functionals, whereas M06-2X was the most precise functional, followed by wB97XD, the other functionals being quite similar among them. Therefore, we concluded that M06-2X, whose calculated geometry is almost coincident with that computed with B3LYP-D3BJ, is the most precise functional to predict the two-color behavior of these fluorescent sensors.

Computational Methods

All the DFT [32] and TDDFT [33] calculations were performed using the B3LYP[34-36], B3LYP-D3BJ [37,38], CAM-B3LYP [39], M06 [40,41], M06-2X [42], M06-L [43-45], PBE0 [46] and ωB97XD [47] functionals. The 6-311+G* and 6-31++G** bases sets [48,49] were used for C, N, O, and H. The DefTZVPP [50] effective-core potential and basis set were used for Na and Ba. NICS calculations were carried out by using the GIAO [51] method. Wiberg bond orders [52] were computed within the NBO bicentric localized orbitals [53,54]. All structures were fully optimized [55] and characterized by harmonic analysis. All the calculations were performed by using the Gaussian 16 suite of programs [56].

Conclusion

From the computational study reported in this paper, we conclude that the benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine scaffold is a convenient fluorophore for barium tagging in neutrinoless double-beta decay. This fluorophore exhibits modular aromaticity in which the central pyrrole ring is less aromatic that the other three rings, as proved by energetic, geometric and magnetic criteria of aromaticity. The lower ground state aromaticity of the tetracyclic system, as a whole, results in a highly fluorescent signal in the first singlet excited state. Analysis of the crown-ether component permits to conclude that the aza-analog equivalent to 18-crown-6 represents the best compromise between coordinating oxygen atoms and ability to form a π–Ba2+ complex with the para-phenylene component of the sensor. Rotation about the dihedral angle defined by the two aromatic components of the sensor result in an essentially planar conformation at the free state, whereas binding to a naked barium cation results in a perpendicular arrangement between the benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine and the 1,4-phenylene components, thus promoting a blue shift responsible for the bicolor behavior of the sensor. Interaction with barium perchlorate results in a slightly different coordination pattern, although the bicolor behavior observed in the experimental fluorescence spectra is preserved. These photophysical properties were observed in DFT and TDDFT calculations. Although the calculated geometries were found to be very similar, the emission wavelengths varied significantly depending upon the functional used.

These conclusions have permitted us to design a second generation of fluorescent bicolor sensors with modifications at the benzo[a]imidazo[5,1,2-cd]indolizine scaffold. The chemical synthesis, photophysical properties and suitability for barium tagging will be published in due course.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the SGI/IZO-SGIker of the UPV/EHU and the DIPC for the generous allocation of analytical and computational resources.

Funding

Financial support for this work was provided by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European's Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (H2020 ERC-SyG 951281), by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (Grant PID2023-151549NB-I00, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, EU) and by the Gobierno Vasco/Eusko Jaurlaritza (GV/EJ, Grant IT-1553-22).

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Goeppert-Mayer, M. Phys. Rev. 1935, 48, 512–516. doi:10.1103/physrev.48.512

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Giuliani, A.; Poves, A. Adv. High Energy Phys. (Hoboken, NJ, U. S.) 2012, 857016. doi:10.1155/2012/857016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majorana, E. Il Nuovo Cim. 1937, 14, 171–184. doi:10.1007/bf02961314

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Planck Collaboration; Aghanim, N.; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A. J.; Barreiro, R. B.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; Battye, R.; Benabed, K.; Bernard, J.-P.; Bersanelli, M.; Bielewicz, P.; Bock, J. J.; Bond, J. R.; Borrill, J.; Bouchet, F. R.; Boulanger, F.; Bucher, M.; Burigana, C.; Butler, R. C.; Calabrese, E.; Cardoso, J.-F.; Carron, J.; Challinor, A.; Chiang, H. C.; Chluba, J.; Colombo, L. P. L.; Combet, C.; Contreras, D.; Crill, B. P.; Cuttaia, F.; de Bernardis, P.; de Zotti, G.; Delabrouille, J.; Delouis, J.-M.; Di Valentino, E.; Diego, J. M.; Doré, O.; Douspis, M.; Ducout, A.; Dupac, X.; Dusini, S.; Efstathiou, G.; Elsner, F.; Enßlin, T. A.; Eriksen, H. K.; Fantaye, Y.; Farhang, M.; Fergusson, J.; Fernandez-Cobos, R.; Finelli, F.; Forastieri, F.; Frailis, M.; Fraisse, A. A.; Franceschi, E.; Frolov, A.; Galeotta, S.; Galli, S.; Ganga, K.; Génova-Santos, R. T.; Gerbino, M.; Ghosh, T.; González-Nuevo, J.; Górski, K. M.; Gratton, S.; Gruppuso, A.; Gudmundsson, J. E.; Hamann, J.; Handley, W.; Hansen, F. K.; Herranz, D.; Hildebrandt, S. R.; Hivon, E.; Huang, Z.; Jaffe, A. H.; Jones, W. C.; Karakci, A.; Keihänen, E.; Keskitalo, R.; Kiiveri, K.; Kim, J.; Kisner, T. S.; Knox, L.; Krachmalnicoff, N.; Kunz, M.; Kurki-Suonio, H.; Lagache, G.; Lamarre, J.-M.; Lasenby, A.; Lattanzi, M.; Lawrence, C. R.; Le Jeune, M.; Lemos, P.; Lesgourgues, J.; Levrier, F.; Lewis, A.; Liguori, M.; Lilje, P. B.; Lilley, M.; Lindholm, V.; López-Caniego, M.; Lubin, P. M.; Ma, Y.-Z.; Macías-Pérez, J. F.; Maggio, G.; Maino, D.; Mandolesi, N.; Mangilli, A.; Marcos-Caballero, A.; Maris, M.; Martin, P. G.; Martinelli, M.; Martínez-González, E.; Matarrese, S.; Mauri, N.; McEwen, J. D.; Meinhold, P. R.; Melchiorri, A.; Mennella, A.; Migliaccio, M.; Millea, M.; Mitra, S.; Miville-Deschênes, M.-A.; Molinari, D.; Montier, L.; Morgante, G.; Moss, A.; Natoli, P.; Nørgaard-Nielsen, H. U.; Pagano, L.; Paoletti, D.; Partridge, B.; Patanchon, G.; Peiris, H. V.; Perrotta, F.; Pettorino, V.; Piacentini, F.; Polastri, L.; Polenta, G.; Puget, J.-L.; Rachen, J. P.; Reinecke, M.; Remazeilles, M.; Renzi, A.; Rocha, G.; Rosset, C.; Roudier, G.; Rubiño-Martín, J. A.; Ruiz-Granados, B.; Salvati, L.; Sandri, M.; Savelainen, M.; Scott, D.; Shellard, E. P. S.; Sirignano, C.; Sirri, G.; Spencer, L. D.; Sunyaev, R.; Suur-Uski, A.-S.; Tauber, J. A.; Tavagnacco, D.; Tenti, M.; Toffolatti, L.; Tomasi, M.; Trombetti, T.; Valenziano, L.; Valiviita, J.; Van Tent, B.; Vibert, L.; Vielva, P.; Villa, F.; Vittorio, N.; Wandelt, B. D.; Wehus, I. K.; White, M.; White, S. D. M.; Zacchei, A.; Zonca, A. Astronom. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833910

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fukugita, M.; Yanagida, T. Phys. Lett. B 1986, 174, 45–47. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(86)91126-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nygren, D. R. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2015, 650, 012002. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/650/1/012002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Freixa, Z.; Rivilla, I.; Monrabal, F.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J.; Cossío, F. P. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 15440–15457. doi:10.1039/d1cp01203g

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Rivilla, I.; Aparicio, B.; Bueno, J. M.; Casanova, D.; Tonnelé, C.; Freixa, Z.; Herrero, P.; Rogero, C.; Miranda, J. I.; Martínez-Ojeda, R. M.; Monrabal, F.; Olave, B.; Schäfer, T.; Artal, P.; Nygren, D.; Cossío, F. P.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J. Nature 2020, 583, 48–54. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2431-5

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Herrero-Gómez, P.; Calupitan, J. P.; Ilyn, M.; Berdonces-Layunta, A.; Wang, T.; de Oteyza, D. G.; Corso, M.; González-Moreno, R.; Rivilla, I.; Aparicio, B.; Aranburu, A. I.; Freixa, Z.; Monrabal, F.; Cossío, F. P.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J.; Rogero, C.; Adams, C.; Almazán, H.; Álvarez, V.; Arazi, L.; Arnquist, I. J.; Ayet, S.; Azevedo, C. D. R.; Bailey, K.; Ballester, F.; Benlloch-Rodríguez, J. M.; Borges, F. I. G. M.; Bounasser, S.; Byrnes, N.; Cárcel, S.; Carrión, J. V.; Cebrián, S.; Church, E.; Conde, C. A. N.; Contreras, T.; Denisenko, A. A.; Dey, E.; Díaz, G.; Dickel, T.; Escada, J.; Esteve, R.; Fahs, A.; Felkai, R.; Fernandes, L. M. P.; Ferrario, P.; Ferreira, A. L.; Foss, F. W.; Freitas, E. D. C.; Freixa, Z.; Generowicz, J.; Goldschmidt, A.; González-Moreno, R.; Guenette, R.; Haefner, J.; Hafidi, K.; Hauptman, J.; Henriques, C. A. O.; Morata, J. A. H.; Herrero, V.; Ho, J.; Ho, P.; Ifergan, Y.; Jones, B. J. P.; Kekic, M.; Labarga, L.; Larizgoitia, L.; Lebrun, P.; Gutierrez, D. L.; López-March, N.; Madigan, R.; Mano, R. D. P.; Martín-Albo, J.; Martínez-Lema, G.; Martínez-Vara, M.; Meziani, Z. E.; Miller, R.; Mistry, K.; Monteiro, C. M. B.; Mora, F. J.; Vidal, J. M.; Navarro, K.; Novella, P.; Nuñez, A.; Nygren, D. R.; Oblak, E.; Odriozola-Gimeno, M.; Palmeiro, B.; Para, A.; Querol, M.; Redwine, A. B.; Renner, J.; Ripoll, L.; Rodríguez, J.; Rogers, L.; Romeo, B.; Romo-Luque, C.; Santos, F. P.; dos Santos, J. M. F.; Simón, A.; Sorel, M.; Stanford, C.; Teixeira, J. M. R.; Toledo, J. F.; Torrent, J.; Usón, A.; Veloso, J. F. C. A.; Vuong, T. T.; Waiton, J.; White, J. T. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7741. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-35153-0

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Auria-Luna, F.; Foss, F. W.; Molina-Canteras, J.; Velazco-Cabral, I.; Marauri, A.; Larumbe, A.; Aparicio, B.; Vázquez, J. L.; Alberro, N.; Arrastia, I.; Nacianceno, V. S.; Colom, A.; Marcuello, C.; Jones, B. J. P.; Nygren, D.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J.; Rogero, C.; Rivilla, I.; Cossío, F. P.; the NEXT collaboration. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2025, 2, 185–199. doi:10.1039/d4lf00227j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Balaban, A. T.; Oniciu, D. C.; Katritzky, A. R. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2777–2812. doi:10.1021/cr0306790

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Glukhovtsev, M. J. Chem. Educ. 1997, 74, 132. doi:10.1021/ed074p132

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krygowski, T. M.; Cyrański, M. K. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1385–1420. doi:10.1021/cr990326u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Z.; Wannere, C. S.; Corminboeuf, C.; Puchta, R.; Schleyer, P. v. R. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842–3888. doi:10.1021/cr030088+

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gershoni-Poranne, R.; Stanger, A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6597–6615. doi:10.1039/c5cs00114e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Solà, M. Front. Chem. (Lausanne, Switz.) 2017, 5, 22. doi:10.3389/fchem.2017.00022

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Poater, J.; Duran, M.; Solà, M.; Silvi, B. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3911–3947. doi:10.1021/cr030085x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Merino, G.; Solà, M.; Fernández, I.; Foroutan-Nejad, C.; Lazzeretti, P.; Frenking, G.; Anderson, H. L.; Sundholm, D.; Cossío, F. P.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Wu, J.; Wu, J. I.; Restrepo, A. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 5569–5576. doi:10.1039/d2sc04998h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wheeler, S. E.; Houk, K. N.; Schleyer, P. v. R.; Allen, W. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2547–2560. doi:10.1021/ja805843n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schleyer, P. v. R.; Pühlhofer, F. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 2873–2876. doi:10.1021/ol0261332

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krygowski, T. M. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1993, 33, 70–78. doi:10.1021/ci00011a011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Craig, N. C.; Groner, P.; McKean, D. C. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 7461–7469. doi:10.1021/jp060695b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arpa, E. M.; Stafström, S.; Durbeej, B. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 1297–1308. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.4c02475

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Geuenich, D.; Hess, K.; Köhler, F.; Herges, R. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3758–3772. doi:10.1021/cr0300901

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morao, I.; Cossío, F. P. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 1868–1874. doi:10.1021/jo981862+

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cossío, F. P.; Morao, I.; Jiao, H.; Schleyer, P. v. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 6737–6746. doi:10.1021/ja9831397

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leyva-Parra, L.; Pino-Rios, R.; Inostroza, D.; Solà, M.; Alonso, M.; Tiznado, W. Chem. – Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202302415. doi:10.1002/chem.202302415

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rosenberg, M.; Dahlstrand, C.; Kilså, K.; Ottosson, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5379–5425. doi:10.1021/cr300471v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arpa, E. M.; Durbeej, B. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 16763–16771. doi:10.1039/d3cp00842h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, J.; Yim, D.; Jang, W.-D.; Yoon, J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2437–2458. doi:10.1039/c6cs00619a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Karplus, M. J. Chem. Phys. 1959, 30, 11–15. doi:10.1063/1.1729860

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cohen, A. J.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Yang, W. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 289–320. doi:10.1021/cr200107z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schirmer, J. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 4992–5005. doi:10.1039/d4cp04551c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Becke, A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. doi:10.1063/1.464913

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R. G. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. doi:10.1103/physrevb.37.785

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vosko, S. H.; Wilk, L.; Nusair, M. Can. J. Phys. 1980, 58, 1200–1211. doi:10.1139/p80-159

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. doi:10.1063/1.3382344

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. doi:10.1002/jcc.21759

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yanai, T.; Tew, D. P.; Handy, N. C. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2004.06.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 5121–5129. doi:10.1021/jp060231d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 13126–13130. doi:10.1021/jp066479k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. doi:10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jacquemin, D.; Perpète, E. A.; Ciofini, I.; Adamo, C.; Valero, R.; Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 2071–2085. doi:10.1021/ct100119e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. doi:10.1021/ar700111a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Y.; Verma, P.; Jin, X.; Truhlar, D. G.; He, X. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 10257–10262. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810421115

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Adamo, C.; Cossi, M.; Barone, V. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1999, 493, 145–157. doi:10.1016/s0166-1280(99)00235-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. doi:10.1039/b810189b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

McLean, A. D.; Chandler, G. S. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 5639–5648. doi:10.1063/1.438980

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J. S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J. A. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. doi:10.1063/1.438955

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wadt, W. R.; Hay, P. J. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 284–298. doi:10.1063/1.448800

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ditchfield, R. Mol. Phys. 1974, 27, 789–807. doi:10.1080/00268977400100711

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wiberg, K. B. Tetrahedron 1968, 24, 1083–1096. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(68)88057-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Foster, J. P.; Weinhold, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 7211–7218. doi:10.1021/ja00544a007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reed, A. E.; Weinhold, F. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 1736–1740. doi:10.1063/1.449360

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schlegel, H. B. J. Comput. Chem. 1982, 3, 214–218. doi:10.1002/jcc.540030212

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gaussian 16, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 8. | Rivilla, I.; Aparicio, B.; Bueno, J. M.; Casanova, D.; Tonnelé, C.; Freixa, Z.; Herrero, P.; Rogero, C.; Miranda, J. I.; Martínez-Ojeda, R. M.; Monrabal, F.; Olave, B.; Schäfer, T.; Artal, P.; Nygren, D.; Cossío, F. P.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J. Nature 2020, 583, 48–54. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2431-5 |

| 32. | Cohen, A. J.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Yang, W. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 289–320. doi:10.1021/cr200107z |

| 33. | Schirmer, J. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 4992–5005. doi:10.1039/d4cp04551c |

| 5. | Fukugita, M.; Yanagida, T. Phys. Lett. B 1986, 174, 45–47. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(86)91126-3 |

| 19. | Wheeler, S. E.; Houk, K. N.; Schleyer, P. v. R.; Allen, W. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2547–2560. doi:10.1021/ja805843n |

| 46. | Adamo, C.; Cossi, M.; Barone, V. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1999, 493, 145–157. doi:10.1016/s0166-1280(99)00235-3 |

| 4. | Planck Collaboration; Aghanim, N.; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A. J.; Barreiro, R. B.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; Battye, R.; Benabed, K.; Bernard, J.-P.; Bersanelli, M.; Bielewicz, P.; Bock, J. J.; Bond, J. R.; Borrill, J.; Bouchet, F. R.; Boulanger, F.; Bucher, M.; Burigana, C.; Butler, R. C.; Calabrese, E.; Cardoso, J.-F.; Carron, J.; Challinor, A.; Chiang, H. C.; Chluba, J.; Colombo, L. P. L.; Combet, C.; Contreras, D.; Crill, B. P.; Cuttaia, F.; de Bernardis, P.; de Zotti, G.; Delabrouille, J.; Delouis, J.-M.; Di Valentino, E.; Diego, J. M.; Doré, O.; Douspis, M.; Ducout, A.; Dupac, X.; Dusini, S.; Efstathiou, G.; Elsner, F.; Enßlin, T. A.; Eriksen, H. K.; Fantaye, Y.; Farhang, M.; Fergusson, J.; Fernandez-Cobos, R.; Finelli, F.; Forastieri, F.; Frailis, M.; Fraisse, A. A.; Franceschi, E.; Frolov, A.; Galeotta, S.; Galli, S.; Ganga, K.; Génova-Santos, R. T.; Gerbino, M.; Ghosh, T.; González-Nuevo, J.; Górski, K. M.; Gratton, S.; Gruppuso, A.; Gudmundsson, J. E.; Hamann, J.; Handley, W.; Hansen, F. K.; Herranz, D.; Hildebrandt, S. R.; Hivon, E.; Huang, Z.; Jaffe, A. H.; Jones, W. C.; Karakci, A.; Keihänen, E.; Keskitalo, R.; Kiiveri, K.; Kim, J.; Kisner, T. S.; Knox, L.; Krachmalnicoff, N.; Kunz, M.; Kurki-Suonio, H.; Lagache, G.; Lamarre, J.-M.; Lasenby, A.; Lattanzi, M.; Lawrence, C. R.; Le Jeune, M.; Lemos, P.; Lesgourgues, J.; Levrier, F.; Lewis, A.; Liguori, M.; Lilje, P. B.; Lilley, M.; Lindholm, V.; López-Caniego, M.; Lubin, P. M.; Ma, Y.-Z.; Macías-Pérez, J. F.; Maggio, G.; Maino, D.; Mandolesi, N.; Mangilli, A.; Marcos-Caballero, A.; Maris, M.; Martin, P. G.; Martinelli, M.; Martínez-González, E.; Matarrese, S.; Mauri, N.; McEwen, J. D.; Meinhold, P. R.; Melchiorri, A.; Mennella, A.; Migliaccio, M.; Millea, M.; Mitra, S.; Miville-Deschênes, M.-A.; Molinari, D.; Montier, L.; Morgante, G.; Moss, A.; Natoli, P.; Nørgaard-Nielsen, H. U.; Pagano, L.; Paoletti, D.; Partridge, B.; Patanchon, G.; Peiris, H. V.; Perrotta, F.; Pettorino, V.; Piacentini, F.; Polastri, L.; Polenta, G.; Puget, J.-L.; Rachen, J. P.; Reinecke, M.; Remazeilles, M.; Renzi, A.; Rocha, G.; Rosset, C.; Roudier, G.; Rubiño-Martín, J. A.; Ruiz-Granados, B.; Salvati, L.; Sandri, M.; Savelainen, M.; Scott, D.; Shellard, E. P. S.; Sirignano, C.; Sirri, G.; Spencer, L. D.; Sunyaev, R.; Suur-Uski, A.-S.; Tauber, J. A.; Tavagnacco, D.; Tenti, M.; Toffolatti, L.; Tomasi, M.; Trombetti, T.; Valenziano, L.; Valiviita, J.; Van Tent, B.; Vibert, L.; Vielva, P.; Villa, F.; Vittorio, N.; Wandelt, B. D.; Wehus, I. K.; White, M.; White, S. D. M.; Zacchei, A.; Zonca, A. Astronom. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833910 |

| 20. | Schleyer, P. v. R.; Pühlhofer, F. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 2873–2876. doi:10.1021/ol0261332 |

| 47. | Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. doi:10.1039/b810189b |

| 14. | Chen, Z.; Wannere, C. S.; Corminboeuf, C.; Puchta, R.; Schleyer, P. v. R. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842–3888. doi:10.1021/cr030088+ |

| 15. | Gershoni-Poranne, R.; Stanger, A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6597–6615. doi:10.1039/c5cs00114e |

| 42. | Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. doi:10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x |

| 2. | Giuliani, A.; Poves, A. Adv. High Energy Phys. (Hoboken, NJ, U. S.) 2012, 857016. doi:10.1155/2012/857016 |

| 16. | Solà, M. Front. Chem. (Lausanne, Switz.) 2017, 5, 22. doi:10.3389/fchem.2017.00022 |

| 17. | Poater, J.; Duran, M.; Solà, M.; Silvi, B. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3911–3947. doi:10.1021/cr030085x |

| 18. | Merino, G.; Solà, M.; Fernández, I.; Foroutan-Nejad, C.; Lazzeretti, P.; Frenking, G.; Anderson, H. L.; Sundholm, D.; Cossío, F. P.; Petrukhina, M. A.; Wu, J.; Wu, J. I.; Restrepo, A. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 5569–5576. doi:10.1039/d2sc04998h |

| 43. | Jacquemin, D.; Perpète, E. A.; Ciofini, I.; Adamo, C.; Valero, R.; Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 2071–2085. doi:10.1021/ct100119e |

| 44. | Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. doi:10.1021/ar700111a |

| 45. | Wang, Y.; Verma, P.; Jin, X.; Truhlar, D. G.; He, X. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 10257–10262. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810421115 |

| 10. | Auria-Luna, F.; Foss, F. W.; Molina-Canteras, J.; Velazco-Cabral, I.; Marauri, A.; Larumbe, A.; Aparicio, B.; Vázquez, J. L.; Alberro, N.; Arrastia, I.; Nacianceno, V. S.; Colom, A.; Marcuello, C.; Jones, B. J. P.; Nygren, D.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J.; Rogero, C.; Rivilla, I.; Cossío, F. P.; the NEXT collaboration. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2025, 2, 185–199. doi:10.1039/d4lf00227j |

| 39. | Yanai, T.; Tew, D. P.; Handy, N. C. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2004.06.011 |

| 8. | Rivilla, I.; Aparicio, B.; Bueno, J. M.; Casanova, D.; Tonnelé, C.; Freixa, Z.; Herrero, P.; Rogero, C.; Miranda, J. I.; Martínez-Ojeda, R. M.; Monrabal, F.; Olave, B.; Schäfer, T.; Artal, P.; Nygren, D.; Cossío, F. P.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J. Nature 2020, 583, 48–54. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2431-5 |

| 9. | Herrero-Gómez, P.; Calupitan, J. P.; Ilyn, M.; Berdonces-Layunta, A.; Wang, T.; de Oteyza, D. G.; Corso, M.; González-Moreno, R.; Rivilla, I.; Aparicio, B.; Aranburu, A. I.; Freixa, Z.; Monrabal, F.; Cossío, F. P.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J.; Rogero, C.; Adams, C.; Almazán, H.; Álvarez, V.; Arazi, L.; Arnquist, I. J.; Ayet, S.; Azevedo, C. D. R.; Bailey, K.; Ballester, F.; Benlloch-Rodríguez, J. M.; Borges, F. I. G. M.; Bounasser, S.; Byrnes, N.; Cárcel, S.; Carrión, J. V.; Cebrián, S.; Church, E.; Conde, C. A. N.; Contreras, T.; Denisenko, A. A.; Dey, E.; Díaz, G.; Dickel, T.; Escada, J.; Esteve, R.; Fahs, A.; Felkai, R.; Fernandes, L. M. P.; Ferrario, P.; Ferreira, A. L.; Foss, F. W.; Freitas, E. D. C.; Freixa, Z.; Generowicz, J.; Goldschmidt, A.; González-Moreno, R.; Guenette, R.; Haefner, J.; Hafidi, K.; Hauptman, J.; Henriques, C. A. O.; Morata, J. A. H.; Herrero, V.; Ho, J.; Ho, P.; Ifergan, Y.; Jones, B. J. P.; Kekic, M.; Labarga, L.; Larizgoitia, L.; Lebrun, P.; Gutierrez, D. L.; López-March, N.; Madigan, R.; Mano, R. D. P.; Martín-Albo, J.; Martínez-Lema, G.; Martínez-Vara, M.; Meziani, Z. E.; Miller, R.; Mistry, K.; Monteiro, C. M. B.; Mora, F. J.; Vidal, J. M.; Navarro, K.; Novella, P.; Nuñez, A.; Nygren, D. R.; Oblak, E.; Odriozola-Gimeno, M.; Palmeiro, B.; Para, A.; Querol, M.; Redwine, A. B.; Renner, J.; Ripoll, L.; Rodríguez, J.; Rogers, L.; Romeo, B.; Romo-Luque, C.; Santos, F. P.; dos Santos, J. M. F.; Simón, A.; Sorel, M.; Stanford, C.; Teixeira, J. M. R.; Toledo, J. F.; Torrent, J.; Usón, A.; Veloso, J. F. C. A.; Vuong, T. T.; Waiton, J.; White, J. T. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7741. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-35153-0 |

| 13. | Krygowski, T. M.; Cyrański, M. K. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1385–1420. doi:10.1021/cr990326u |

| 40. | Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 5121–5129. doi:10.1021/jp060231d |

| 41. | Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. G. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 13126–13130. doi:10.1021/jp066479k |

| 7. | Freixa, Z.; Rivilla, I.; Monrabal, F.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J.; Cossío, F. P. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 15440–15457. doi:10.1039/d1cp01203g |

| 34. | Becke, A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. doi:10.1063/1.464913 |

| 35. | Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R. G. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. doi:10.1103/physrevb.37.785 |

| 36. | Vosko, S. H.; Wilk, L.; Nusair, M. Can. J. Phys. 1980, 58, 1200–1211. doi:10.1139/p80-159 |

| 6. | Nygren, D. R. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2015, 650, 012002. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/650/1/012002 |

| 11. | Balaban, A. T.; Oniciu, D. C.; Katritzky, A. R. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2777–2812. doi:10.1021/cr0306790 |

| 37. | Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. doi:10.1063/1.3382344 |

| 38. | Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. doi:10.1002/jcc.21759 |

| 24. | Geuenich, D.; Hess, K.; Köhler, F.; Herges, R. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3758–3772. doi:10.1021/cr0300901 |

| 21. | Krygowski, T. M. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1993, 33, 70–78. doi:10.1021/ci00011a011 |

| 22. | Craig, N. C.; Groner, P.; McKean, D. C. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 7461–7469. doi:10.1021/jp060695b |

| 48. | McLean, A. D.; Chandler, G. S. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 5639–5648. doi:10.1063/1.438980 |

| 49. | Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J. S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J. A. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. doi:10.1063/1.438955 |

| 23. | Arpa, E. M.; Stafström, S.; Durbeej, B. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 1297–1308. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.4c02475 |

| 50. | Wadt, W. R.; Hay, P. J. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 284–298. doi:10.1063/1.448800 |

| 8. | Rivilla, I.; Aparicio, B.; Bueno, J. M.; Casanova, D.; Tonnelé, C.; Freixa, Z.; Herrero, P.; Rogero, C.; Miranda, J. I.; Martínez-Ojeda, R. M.; Monrabal, F.; Olave, B.; Schäfer, T.; Artal, P.; Nygren, D.; Cossío, F. P.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J. Nature 2020, 583, 48–54. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2431-5 |

| 9. | Herrero-Gómez, P.; Calupitan, J. P.; Ilyn, M.; Berdonces-Layunta, A.; Wang, T.; de Oteyza, D. G.; Corso, M.; González-Moreno, R.; Rivilla, I.; Aparicio, B.; Aranburu, A. I.; Freixa, Z.; Monrabal, F.; Cossío, F. P.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J.; Rogero, C.; Adams, C.; Almazán, H.; Álvarez, V.; Arazi, L.; Arnquist, I. J.; Ayet, S.; Azevedo, C. D. R.; Bailey, K.; Ballester, F.; Benlloch-Rodríguez, J. M.; Borges, F. I. G. M.; Bounasser, S.; Byrnes, N.; Cárcel, S.; Carrión, J. V.; Cebrián, S.; Church, E.; Conde, C. A. N.; Contreras, T.; Denisenko, A. A.; Dey, E.; Díaz, G.; Dickel, T.; Escada, J.; Esteve, R.; Fahs, A.; Felkai, R.; Fernandes, L. M. P.; Ferrario, P.; Ferreira, A. L.; Foss, F. W.; Freitas, E. D. C.; Freixa, Z.; Generowicz, J.; Goldschmidt, A.; González-Moreno, R.; Guenette, R.; Haefner, J.; Hafidi, K.; Hauptman, J.; Henriques, C. A. O.; Morata, J. A. H.; Herrero, V.; Ho, J.; Ho, P.; Ifergan, Y.; Jones, B. J. P.; Kekic, M.; Labarga, L.; Larizgoitia, L.; Lebrun, P.; Gutierrez, D. L.; López-March, N.; Madigan, R.; Mano, R. D. P.; Martín-Albo, J.; Martínez-Lema, G.; Martínez-Vara, M.; Meziani, Z. E.; Miller, R.; Mistry, K.; Monteiro, C. M. B.; Mora, F. J.; Vidal, J. M.; Navarro, K.; Novella, P.; Nuñez, A.; Nygren, D. R.; Oblak, E.; Odriozola-Gimeno, M.; Palmeiro, B.; Para, A.; Querol, M.; Redwine, A. B.; Renner, J.; Ripoll, L.; Rodríguez, J.; Rogers, L.; Romeo, B.; Romo-Luque, C.; Santos, F. P.; dos Santos, J. M. F.; Simón, A.; Sorel, M.; Stanford, C.; Teixeira, J. M. R.; Toledo, J. F.; Torrent, J.; Usón, A.; Veloso, J. F. C. A.; Vuong, T. T.; Waiton, J.; White, J. T. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7741. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-35153-0 |

| 7. | Freixa, Z.; Rivilla, I.; Monrabal, F.; Gómez-Cadenas, J. J.; Cossío, F. P. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 15440–15457. doi:10.1039/d1cp01203g |

| 30. | Li, J.; Yim, D.; Jang, W.-D.; Yoon, J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2437–2458. doi:10.1039/c6cs00619a |

| 28. | Rosenberg, M.; Dahlstrand, C.; Kilså, K.; Ottosson, H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5379–5425. doi:10.1021/cr300471v |

| 29. | Arpa, E. M.; Durbeej, B. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 16763–16771. doi:10.1039/d3cp00842h |

| 25. | Morao, I.; Cossío, F. P. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 1868–1874. doi:10.1021/jo981862+ |

| 26. | Cossío, F. P.; Morao, I.; Jiao, H.; Schleyer, P. v. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 6737–6746. doi:10.1021/ja9831397 |

| 52. | Wiberg, K. B. Tetrahedron 1968, 24, 1083–1096. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(68)88057-3 |

| 27. | Leyva-Parra, L.; Pino-Rios, R.; Inostroza, D.; Solà, M.; Alonso, M.; Tiznado, W. Chem. – Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202302415. doi:10.1002/chem.202302415 |

| 53. | Foster, J. P.; Weinhold, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 7211–7218. doi:10.1021/ja00544a007 |

| 54. | Reed, A. E.; Weinhold, F. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 1736–1740. doi:10.1063/1.449360 |

© 2025 Velazco-Cabral et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.