Abstract

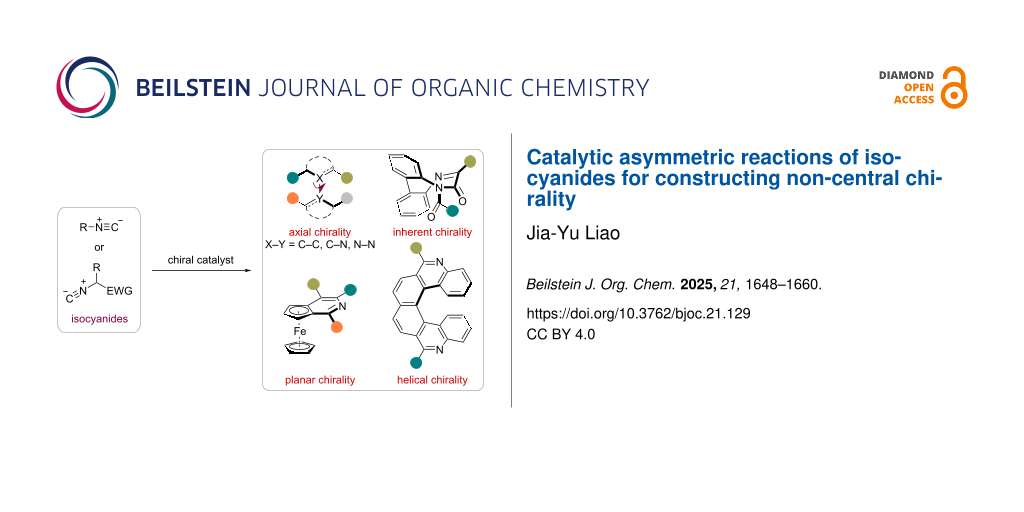

Beyond the conventional carbon-centered chirality, catalytic asymmetric transformations of isocyanides have recently emerged as a powerful strategy for the efficient synthesis of structurally diverse scaffolds featuring axial, planar, helical, and inherent chirality. Herein, we summarize the exciting achievements in this rapidly evolving field. These elegant examples have been organized and presented based on the reaction type as well as the resulting chirality form. Additionally, we provide a perspective on the current limitations and future opportunities, aiming to inspire further advances in this area.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Chirality represents a fundamental property of molecules and manifests in diverse forms (Figure 1a). While central chirality based on stereogenic centers (e.g., C, P, S, etc.) is the most conventional type, non-central chirality, such as axial [1-4], planar [5-7], helical [8-10], and inherent chirality [11,12], has gained increasing attention due to its broad applications in various fields, including but not limited to drug discovery, asymmetric catalysis, and materials science (Figure 1b). Consequently, the development of efficient and stereoselective methods for assembling such scaffolds with respect to structural diversity has become a hot topic in synthetic organic chemistry.

Figure 1: a) Common types of chirality. b) Representative functional molecules bearing non-central chirality.

Figure 1: a) Common types of chirality. b) Representative functional molecules bearing non-central chirality.

Isocyanides (also termed isonitriles) are a class of highly versatile building blocks in organic synthesis, participating in a wide range of transformations including multicomponent reactions (e.g., the well-known Passerini and Ugi reactions) [13-15], insertion reactions [16-18], cycloaddition reactions (e.g., [4 + 1], [3 + 2]) [19,20], and others [21-23]. Particularly, isocyanides have been widely exploited toward the preparation of centrally chiral structures through transition-metal-catalyzed or organocatalytic asymmetric reactions [24-26]. Beyond these great developments, recent efforts have successfully expanded the utility of isocyanides to access structurally diverse non-central chiral frameworks, further expanding their synthetic potential. The following sections highlight these fruitful achievements, organized by both the reaction type and the chirality type of resulting products.

Perspective

Isocyanide-based transformations

Palladium-catalyzed isocyanide insertion reactions

In 2018, Luo, Zhu, and co-workers developed a palladium-catalyzed enantioselective reaction between ferrocene-derived vinyl isocyanides 1 and aryl iodides (Scheme 1a) [27]. This transformation proceeded via two key steps, isocyanide insertion and desymmetric C(sp2)–H bond activation. By using phosphoramidite L1 as the chiral ligand, planar chiral pyridoferrocenes 2 were obtained in 61–99% yield with 72–99% ee. In addition, this catalytic system could be applied to synthesize more complex structures. As shown in Scheme 1b, when N-(2-iodophenyl)methacrylamide 3 and 1a were employed as starting materials, compound 4 bearing nonadjacent planar and central chirality was obtained in good yield and enantioselectivity (4a, 54%, 90% ee; 4b, 32%, 97% ee). However, the diastereoselectivity is modest (1.7:1), likely resulting from insufficient chiral induction during the indolinone-forming step.

Scheme 1: Construction of planar chirality.

Scheme 1: Construction of planar chirality.

Moving forward, this strategy was applied in the construction of axial chirality by the same group. In 2021, they reported a Pd(OAc)2/L2-catalyzed imidoylative cycloamidation of N-alkyl-2-isocyanobenzamides 5 with 2,6-disubstituted aryl iodides 6 (Scheme 2a) [28]. Through a coupling–cyclization reaction sequence, axially chiral 2-arylquinazolinones 7 were synthesized in 35–93% yield with 71–95% ee. Interestingly, by using N-(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-isocyanobenzamide (8) and aryl iodide 6a as the reactants, diastereomeric products 9a and 9b, each containing two distinct stereogenic axes (C–C and C–N), were obtained in 93% and 89% ee, respectively.

Scheme 2: Construction of axial chirality.

Scheme 2: Construction of axial chirality.

Very recently, Luo and co-workers implemented an efficient palladium-catalyzed atroposelective C(sp2)–H imidoylative cyclization of functionalized phenyl isocyanides, guided by DFT calculations (Scheme 2b) [29]. Three types of isocyanides (10–12) were evaluated in reactions with aryl iodides, affording indole-fused N-heteroaryl scaffolds 13–15, featuring either a C–C or C–N stereogenic axis, in moderate-to-high yields with high enantioselectivities.

Beyond planar and axial chirality, the same group developed a three-component coupling reaction of 2,2′-diisocyano-1,1′-biphenyls 16, aryl iodides, and carboxylates (Scheme 3a) [30]. Under chiral palladium catalysis, unique inherently chiral saddle-shaped bridged biaryls 17 were formed through a reaction sequence involving double isocyanide insertion, reductive elimination, and acyl transfer. To be noted, the introduction of a substituent at the ortho-position of the isocyanide group in 16 caused a significant drop in the enantioselectivity (e.g., 17b). Besides, when unsymmetrical diisocyanide was used, the initial isocyanide insertion was found to be non-regioselective, delivering a 1:1 mixture of regioisomers (17c and 17c’). Intriguingly, 17a could act as a chiral acylating reagent, applying in the kinetic resolution of racemic primary amines rac-18. Additionally, after the reaction, the resulting deacylated compound 20 could be recovered in almost quantitative yield without any erosion of the enantiopurity. A possible reaction mechanism for this Pd-catalyzed three-component reaction was proposed (Scheme 3b). As shown, the reaction started with the oxidative addition of phenyl iodide to Pd(0) to generate the phenyl Pd(II) species. After that, coordination and migratory insertion of the first isocyanide group of 16a to Pd(II) delivered INT-I. Then, coordination and migratory insertion of the second isocyanide group occurred to give INT-III, which underwent reductive elimination to afford INT-IV. Finally, migration of the Piv group from O to N gave the product 17a.

Scheme 3: Construction of inherent chirality.

Scheme 3: Construction of inherent chirality.

Moreover, the Pd-catalyzed isocyanide insertion approach has been successfully extended to the generation of helical chirality [31]. As shown in Scheme 4a, phenyl diisocyanides 21 or 22 underwent double C(sp2)–H imidoylative cyclization with aryl iodides, furnishing symmetrical pyrido[6]helicenes 23 or furan-incorporating pyrido[7]helicenes 24 with stable helical chirality, respectively. Furthermore, pre-cyclized monoisocyanides, such as 25a and 25b, were identified as another class of suitable substrates under the standard conditions (Scheme 4b). On one hand, such findings demonstrated that the second cyclization determines enantioselectivity; on the other hand, it provided a practical way to the preparation of unsymmetrical pyrido[6]helicenes 26.

Scheme 4: Construction of helical chirality.

Scheme 4: Construction of helical chirality.

Isocyanide-based multicomponent reactions

Except for Pd-catalyzed isocyanide insertion reactions, organocatalytic isocyanide-based multicomponent reactions have been explored for the synthesis of axially chiral compounds. In 2024, Yang and co-workers reported a catalytic asymmetric version of the Groebke–Blackburn–Bienaymé reaction [32-34] involving 6-aryl-2-aminopyridines 27, aldehydes, and isocyanides (Scheme 5a) [35]. By employing chiral phosphoric acid (CPA) C1 as the catalyst, this reaction worked well to afford axially chiral imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines 28 in high-to-excellent yields (up to 99%) and enantioselectivities (up to >99% ee). It is worth noting that the presence of a hydrogen bonding donor in 27 is crucial for achieving high enantioselectivity. As shown, while replacing the OH with NHMe led to a slight decrease of ee (28c versus 28b), the protection of the OH with methyl caused a severe drop (28d versus 28b). The application of the resulting products in developing chiral organocatalysts was investigated as well. For instance, 28a was converted to a thiourea-tertiary amine 29 through a four-step procedure in an overall 36% yield. This compound was then utilized as the catalyst in the electrophilic amination reaction between β-ketoester 30 and di-tert-butyl azodicarboxylate (31), and the corresponding product 32 was obtained in 99% yield with 88% ee. A plausible reaction mechanism was proposed for this CPA-catalyzed enantioselective Groebke–Blackburn–Bienaymé reaction. As illustrated in Scheme 5b, the imine condensation between 27 and the aldehyde afforded INT-A, which was activated by the CPA catalyst through hydrogen bonding interaction. The nucleophilic addition of isocyanide to Int-A produced INT-B bearing a stereogenic center. Subsequently, INT-B underwent intramolecular cyclization to generate axially chiral INT-C, which, after imine-enamine tautomerization, led to the formation of final product 28.

Scheme 5: CPA-catalyzed enantioselective Groebke–Blackburn–Bienaymé reaction.

Scheme 5: CPA-catalyzed enantioselective Groebke–Blackburn–Bienaymé reaction.

α-Acidic isocyanide-based transformations

De novo arene formation

In 2019, Zhu and co-workers developed the first example of catalytic enantioselective Yamamoto–de Meijere pyrrole synthesis [36,37] between alkynyl ketones 33 and isocyanoacetates (Scheme 6) [38]. The success of this study not only adds a new entry to the de novo arene formation strategy [39,40] but also initiates the application of isocyanoacetates in constructing axial chirality. With Ag2O and quinine-derived amino-phosphine ligand L6 as the chiral catalyst, atropisomeric 3-arylpyrroles 34 were generated in 43–98% yield with 82–96% ee. Notably, two by-products 35 and 36 were observed during the reaction, resulting from the aldol reaction of isocyanoacetates with the ketone moiety in 33. The authors have also demonstrated that 34f could be used as the starting material to prepare the axially chiral olefin-oxazole 37, which might be a potentially useful ligand in asymmetric catalysis. A possible stereochemical model was proposed as well, involving synergistic activation of both the alkynyl ketone and isocyanoacetate by the chiral catalyst.

Scheme 6: Construction of axially chiral 3-arylpyrroles via de novo pyrrole formation.

Scheme 6: Construction of axially chiral 3-arylpyrroles via de novo pyrrole formation.

Central-to-axial chirality transfer

In parallel with Zhu’s work, Du, Chen, and co-workers reported an alternative way for the preparation of axially chiral 3-arylpyrroles [41] through a catalytic asymmetric Barton–Zard reaction [42] via central-to-axial chirality transfer strategy [43,44]. Under a similar silver-based catalytic system, nitroolefins 38 bearing a β-ortho-substituted aryl group reacted smoothly with α-acidic isocyanides to give the corresponding products 39 in 55–99% yield and 57–96% ee (Scheme 7). In addition, nitroolefins 40 possessing a β-five-membered heteroaryl ring were proven to be suitable substrates to react with tert-butyl isocyanoacetate, affording 3-heteroarylpyrroles 41 in 55–99% yield with 70–96% ee. In these cases, additional 2.0 equivalents of DBU were required to facilitate the conversion from the [3 + 2] cycloadducts to the final products. Moreover, an axially chiral tertiary alcohol-phosphine 42 was prepared from 39a through a three-step procedure including N-methylation, reduction of phosphine oxide, and Grignard addition to ester. Subsequently, 42 was applied as a bifunctional Lewis base organocatalyst in the formal [4 + 2] cyclization reaction between alkene 43 and 2,2′-dienone 44. The corresponding spirooxindole 45 was obtained in >19:1 dr, 63% yield, and 89% ee.

Scheme 7: Synthesis of atropoisomeric 3-arylpyrroles via central-to-axial chirality transfer.

Scheme 7: Synthesis of atropoisomeric 3-arylpyrroles via central-to-axial chirality transfer.

Dynamic kinetic resolution of configurationally labile bridged biaryls

The catalytic asymmetric dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) of configurationally labile bridged biaryls, pioneered by Bringmann and co-workers [45], has proven to be a powerful approach for synthesizing axially chiral biaryls, particularly in the challenging case of sterically hindered tetra-ortho-substituted scaffolds [46,47]. In this context, α-acidic isocyanides have been successfully employed as carbon nucleophiles in the DKR of various bridged biaryls bearing different linkages to give diverse nitrogen heterocycle-substituted atropoisomeric biaryls.

In 2021, our group achieved the catalytic enantioselective DKR of biaryl lactones 46 with α-acidic isocyanides (Scheme 8a) [48]. By using Ag2CO3 and cinchonine-derived amino-phosphine L7 as the catalyst, a wide range of oxazole-containing tetra-ortho-substituted axially chiral phenols 47 bearing diverse scaffolds, including naphthyl-phenyl (e.g., 47a), phenyl-naphthyl (e.g., 47b), biphenyl (e.g., 47c), and binaphthyl (e.g., 47d), were obtained in high yields with high enantioselectivities. In terms of isocyanides, isocyanoacetates with different ester groups, p-toluenesulfonylmethyl isocyanide (47e), and isocyanoacetamide (47f), were all compatible. It is noteworthy that this work represents the first example of catalytic asymmetric DKR of Bringmann’s lactones with carbon nucleophiles. The success lies in the tandem enantioselective ring-opening of lactones with α-acidic isocyanides, followed by a rapid cyclization driven by aromatization, overcoming the long-standing stereochemical leakage problem caused by the undesired lactol formation [45].

Scheme 8: Dynamic kinetic resolution of bridged biaryls with α-acidic isocyanides.

Scheme 8: Dynamic kinetic resolution of bridged biaryls with α-acidic isocyanides.

Encouraged by the above results, we turned our attention to biaryl lactams [49]. However, in this case, the inherent resonance stability of the amide bond makes the ring-opening process rather challenging. To solve this problem, we envisioned that a cooperative catalytic system merging silver catalysis and organocatalysis could be employed to activate both reactants simultaneously. After extensive screening, the combination of Ag2CO3 and quinidine-derived squaramide C2 was identified to be the optimal choice of catalyst. A variety of ortho,ortho-disubstituted biaryl lactams 48 were facilely transformed into the corresponding tetra-ortho-substituted atropisomeric anilines 49 in high yields with excellent enantioselectivities (Scheme 8b). In contrast, lactams possessing only one ortho substituent suffered from much lower reactivity (e.g., 49c), presumably due to the lack of sufficient torsional strain [50], whereas substrates bearing strong electron-withdrawing groups resulted in almost no reactivity (e.g., 49d).

Additionally, it was found that the N-substituent R3 in 48 has a significant effect on both reactivity and enantioselectivity. While replacing Ts with Bn led to no reaction at all (49e versus 49a), substituting it with Cbz gave the desired product 49f in only 6% yield with <5% ee.

In 2022, we reported the discovery and development of a torsional strain-independent reaction between biaryl thionolactones 50 and α-acidic isocyanides (Scheme 8c) [51]. Using Ag2O and 1,2-diaminocyclohexane-derived phosphine-squaramide bifunctional ligand L8 as the catalyst, a universal synthesis of tri- and tetra-ortho-substituted biaryl phenols 51 containing a thiazole moiety was achieved in 85–99% yield with 56–99% ee. It is worth mentioning that this work represents the first example of catalytic asymmetric DKR of biaryl thionolactones, getting rid of the pre-formation of stoichiometric Ru-complexes [52,53]. Mechanistic investigations indicated that this transformation proceeds through a two-step sequence promoted by the same catalyst: 1) the diastereo- and enantioselective [3 + 2] cycloaddition to generate spiro-S,O-ketal 52 with both axial and central chirality, followed by 2) ring-strain and aromatization-driven elimination, which elucidating the observed unusual torsional strain-independent reactivity. In addition, products bearing a tert-butyl ester group were smoothly converted into structurally novel axially chiral eight-membered lactones 53 in 42–67% yield with excellent retention of enantiopurity via an overall lactonization process.

In addition to C–C axial chirality, we have demonstrated that our Ag-catalyzed DKR protocol could be applied for the generation of C–N atropisomers by using N-arylindole lactams 54 as the cross-partner [54]. By employing Ag2CO3 and L6 as the catalyst, axially chiral N-arylindoles 55 were synthesized in 36–94% yield with 26–90% ee (Scheme 8d). Building on such results, a one-pot procedure involving DKR, hydrolysis, and lactamization was developed, enabling a practical synthesis of structurally novel atropisomeric N-arylindoles 56 bearing an eight-membered lactam in 51–85% yield with 54–92% ee. Of note, these scaffolds exhibited remarkably large Stokes shifts, showing great potential in the development of fluorescent dyes.

Desymmetrization of prochiral compounds

Beyond DKR of bridged biaryls, our group has successfully applied α-acidic isocyanides in the catalytic asymmetric desymmetrization of substrates featuring a prochiral axis, realizing the preparation of structurally complex scaffolds possessing both axial and central chirality. Notably, in these cases, both issues of diastereo- and enantioselectivity are required to be addressed appropriately to prevent forming a complex mixture of stereoisomers.

In 2022, our group developed a silver-catalyzed desymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition between prochiral N-aryl maleimides 57 and α-substituted α-acidic isocyanides (Scheme 9a) [55]. With Ag2CO3 and L9 as the chiral catalyst, this reaction proceeded smoothly to produce highly functionalized bicyclic 1-pyrrolines 58 bearing a remote C–N stereogenic axis and three contiguous stereogenic carbon centers in high yields (up to 97%) with high stereoselectivities (up to >20:1 dr, 99% ee).

Scheme 9: Desymmetrization of prochiral compounds with α-acidic isocyanides.

Scheme 9: Desymmetrization of prochiral compounds with α-acidic isocyanides.

Subsequently, we expanded this methodology to prochiral N-quinazolinone maleimides 59, achieving the simultaneous generation of N–N axial and central chirality within a single step (Scheme 9b) [56]. Of particular note, an interesting ligand-induced diastereodivergent profile was identified. While the employment of L9 afforded endo-selective [3 + 2] cycloadducts 60, using Trost ligand L10 resulted in a complete reversal to the exo-cycloadducts 61. DFT calculations were performed and indicated that these two ligands act in different ways in the cyclization process, providing explanations for such a diastereodivergence. Specifically, L9 functions as a monodentate ligand, and the stronger ligand–substrate hydrogen-bonding interaction and smaller distortion of the ligand resulted in endo-cycloadducts (L9-TS). In contrast, Trost ligand L10 serves as a bidentate ligand, and the smaller distortion of isocyanoacetate–Ag coordination combing with better Ag–C σ-orbital overlap led to exo-cycloadducts (L10-TS).

Except for constructing C–N and N–N axial chirality, we have developed a highly diastereo- and enantioselective method to access tri- and tetra-ortho-substituted biaryl aldehydes 63 bearing both C–C axial and central chirality (Scheme 9c) [57]. Key to this work relies on the implementation of an efficient Ag2O/L7-catalyzed desymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition of prochiral biaryl dialdehydes 62 with α-substituted α-acidic isocyanides. We have also demonstrated that the retained aldehyde functionality in 63 allowed for versatile derivatizations, such as reduction, reductive amination, condensation, and olefination, which further expanded the structural diversity of the resulting products.

Summary and Outlook

The past few years have witnessed exciting progress in developing catalytic asymmetric transformations of isocyanides for generating architectures bearing axial, planar, helical, and inherent chirality. These advances not only offer efficient routes to enantioenriched non-central chiral compounds but also significantly broaden the utility of isocyanides in organic synthesis. Nevertheless, despite these notable accomplishments, this research field remains in its nascent stage with ample room for further exploration. First, existing studies have predominantly focused on the construction of axial chirality, while synthetic methods for other forms of non-central chirality, such as planar, helical, and inherent chirality, remain largely underdeveloped. To date, only a single example has been reported for each case, all of which are restricted to palladium-catalyzed isocyanide insertion reactions. Second, the catalytic systems employed thus far are relatively limited. Although transition metal catalysis, particularly with palladium and silver, has proven to be highly effective, expanding the scope as well as the activation mode of chiral catalysts could greatly enrich reaction types and accessible structural diversity. Third, further investigation into the potential applications of the resulting chiral products, e.g., biological activities and utility as chiral organocatalysts or ligands, warrants greater attention. We anticipate that considerable efforts in these directions would be crucial for advancing this field and fully unlocking the synthetic potential of isocyanides in the preparation of non-central chiral compounds.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data was generated or analyzed in this study.

References

-

Wencel-Delord, J.; Panossian, A.; Leroux, F. R.; Colobert, F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3418–3430. doi:10.1039/c5cs00012b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheng, J. K.; Xiang, S.-H.; Li, S.; Ye, L.; Tan, B. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4805–4902. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01306

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Carmona, J. A.; Rodríguez-Franco, C.; Fernández, R.; Hornillos, V.; Lassaletta, J. M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2968–2983. doi:10.1039/d0cs00870b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schmidt, T. A.; Hutskalova, V.; Sparr, C. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 497–517. doi:10.1038/s41570-024-00618-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

López, R.; Palomo, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202113504. doi:10.1002/anie.202113504

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Laws, D.; Poff, C. D.; Heyboer, E. M.; Blakey, S. B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 6003–6030. doi:10.1039/d3cs00325f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, G.; Wang, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202412805. doi:10.1002/anie.202412805

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tanaka, K.; Morita, F. J. Synth. Org. Chem., Jpn. 2022, 80, 1019–1027. doi:10.5059/yukigoseikyokaishi.80.1019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.-G.; Shi, F. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 3077–3111. doi:10.1016/j.checat.2022.10.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, Q.; Tang, Y.-P.; Zhang, C.-G.; Wang, Z.; Dai, L. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 16256–16265. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c05345

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tang, M.; Yang, X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300738. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202300738

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 5307–5322. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5c00479

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dömling, A.; Ugi, I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3168–3210. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3168::aid-anie3168>3.0.co;2-u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dömling, A. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 17–89. doi:10.1021/cr0505728

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sadjadi, S.; Heravi, M. M.; Nazari, N. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 53203–53272. doi:10.1039/c6ra02143c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qiu, G.; Ding, Q.; Wu, J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5257–5269. doi:10.1039/c3cs35507a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Song, B.; Xu, B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1103–1123. doi:10.1039/c6cs00384b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Collet, J. W.; Roose, T. R.; Ruijter, E.; Maes, B. U. W.; Orru, R. V. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 540–558. doi:10.1002/anie.201905838

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kaur, T.; Wadhwa, P.; Bagchi, S.; Sharma, A. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 6958–6976. doi:10.1039/c6cc01562j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Doraghi, F.; Baghershahi, P.; Gilaninezhad, F.; Darban, N. M. Z.; Dastyafteh, N.; Noori, M.; Mahdavi, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2025, 367, e202400994. doi:10.1002/adsc.202400994

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gulevich, A. V.; Zhdanko, A. G.; Orru, R. V. A.; Nenajdenko, V. G. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5235–5331. doi:10.1021/cr900411f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boyarskiy, V. P.; Bokach, N. A.; Luzyanin, K. V.; Kukushkin, V. Y. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2698–2779. doi:10.1021/cr500380d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Giustiniano, M.; Basso, A.; Mercalli, V.; Massarotti, A.; Novellino, E.; Tron, G. C.; Zhu, J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1295–1357. doi:10.1039/c6cs00444j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

van Berkel, S. S.; Bögels, B. G. M.; Wijdeven, M. A.; Westermann, B.; Rutjes, F. P. J. T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 3543–3559. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201200030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Q.; Wang, D.-X.; Wang, M.-X.; Zhu, J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1290–1300. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, J.; Chen, G.-S.; Chen, S.-J.; Li, Z.-D.; Liu, Y.-L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 6598–6619. doi:10.1002/chem.202003224

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, S.; Xiong, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Q. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1837–1840. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00348

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Teng, F.; Yu, T.; Peng, Y.; Hu, W.; Hu, H.; He, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2722–2728. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c00640

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Luo, S. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 201–210. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c06720

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, Y.; Cheng, S.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Gan, C.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. CCS Chem. 2022, 4, 2897–2905. doi:10.31635/ccschem.021.202101486

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, T.; Li, Z.-Q.; Li, J.; Cheng, S.; Xu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhong, Y.-W.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 13034–13041. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c04461

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Groebke, K.; Weber, L.; Mehlin, F. Synlett 1998, 661–663. doi:10.1055/s-1998-1721

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blackburn, C.; Guan, B.; Fleming, P.; Shiosaki, K.; Tsai, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 3635–3638. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(98)00653-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bienaymé, H.; Bouzid, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2234–2237. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2234::aid-anie2234>3.3.co;2-i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hong, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr6135. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adr6135

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kamijo, S.; Kanazawa, C.; Yamamoto, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9260–9266. doi:10.1021/ja051875m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Larionov, O. V.; de Meijere, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5664–5667. doi:10.1002/anie.200502140

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zheng, S.-C.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1494–1498. doi:10.1002/anie.201812654

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Shao, H.; Ma, X. Molecules 2022, 27, 8517. doi:10.3390/molecules27238517

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, H.-R.; Sharif, A.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202300183. doi:10.1002/chem.202300183

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, X.-L.; Zhao, H.-R.; Song, X.; Jiang, B.; Du, W.; Chen, Y.-C. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 4374–4381. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b00767

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barton, D. H. R.; Zard, S. Z. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985, 1098–1100. doi:10.1039/c39850001098

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L. Chem. – Asian J. 2020, 15, 2939–2951. doi:10.1002/asia.202000681

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Min, X.-L.; Zhang, X.-L.; Shen, R.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 2280–2292. doi:10.1039/d1qo01699g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bringmann, G.; Breuning, M.; Tasler, S. Synthesis 1999, 525–558. doi:10.1055/s-1999-3435

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wang, G.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Z. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4507–4521. doi:10.1039/d2qo00946c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, C.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, R.; Dou, X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400402. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202400402

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qian, L.; Tao, L.-F.; Wang, W.-T.; Jameel, E.; Luo, Z.-H.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, J.-Y. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 5086–5091. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01632

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, W.-T.; Zhang, S.; Tao, L.-F.; Pan, Z.-Q.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 6292–6295. doi:10.1039/d2cc01625g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, K.; Duan, L.; Xu, S.; Jiang, J.; Fu, Y.; Gu, Z. Chem 2018, 4, 599–612. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.01.017

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, Z.-H.; Wang, W.-T.; Tang, T.-Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, F.; Hu, D.; Tao, L.-F.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202211303. doi:10.1002/anie.202211303

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schenk, W. A.; Kümmel, J.; Reuther, I.; Burzlaff, N.; Wuzik, A.; Schupp, O.; Bringmann, G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 1745–1756. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0682(199910)1999:10<1745::aid-ejic1745>3.3.co;2-t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bringmann, G.; Wuzik, A.; Kümmel, J.; Schenk, W. A. Organometallics 2001, 20, 1692–1694. doi:10.1021/om001040e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tao, L.-F.; Huang, F.; Zhao, X.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101697. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101697

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, S.; Luo, Z.-H.; Wang, W.-T.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4645–4649. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01761

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, W.-T.; Zhang, S.; Lin, W.; Luo, Z.-H.; Hu, D.; Huang, F.; Bai, R.; Lan, Y.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 3308–3319. doi:10.1039/d4qo00294f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, F.; Tao, L.-F.; Liu, J.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 4487–4490. doi:10.1039/d3cc00708a

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 50. | Zhao, K.; Duan, L.; Xu, S.; Jiang, J.; Fu, Y.; Gu, Z. Chem 2018, 4, 599–612. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.01.017 |

| 51. | Luo, Z.-H.; Wang, W.-T.; Tang, T.-Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, F.; Hu, D.; Tao, L.-F.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202211303. doi:10.1002/anie.202211303 |

| 52. | Schenk, W. A.; Kümmel, J.; Reuther, I.; Burzlaff, N.; Wuzik, A.; Schupp, O.; Bringmann, G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 1745–1756. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0682(199910)1999:10<1745::aid-ejic1745>3.3.co;2-t |

| 53. | Bringmann, G.; Wuzik, A.; Kümmel, J.; Schenk, W. A. Organometallics 2001, 20, 1692–1694. doi:10.1021/om001040e |

| 1. | Wencel-Delord, J.; Panossian, A.; Leroux, F. R.; Colobert, F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3418–3430. doi:10.1039/c5cs00012b |

| 2. | Cheng, J. K.; Xiang, S.-H.; Li, S.; Ye, L.; Tan, B. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4805–4902. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01306 |

| 3. | Carmona, J. A.; Rodríguez-Franco, C.; Fernández, R.; Hornillos, V.; Lassaletta, J. M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2968–2983. doi:10.1039/d0cs00870b |

| 4. | Schmidt, T. A.; Hutskalova, V.; Sparr, C. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 497–517. doi:10.1038/s41570-024-00618-x |

| 13. | Dömling, A.; Ugi, I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3168–3210. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3168::aid-anie3168>3.0.co;2-u |

| 14. | Dömling, A. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 17–89. doi:10.1021/cr0505728 |

| 15. | Sadjadi, S.; Heravi, M. M.; Nazari, N. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 53203–53272. doi:10.1039/c6ra02143c |

| 32. | Groebke, K.; Weber, L.; Mehlin, F. Synlett 1998, 661–663. doi:10.1055/s-1998-1721 |

| 33. | Blackburn, C.; Guan, B.; Fleming, P.; Shiosaki, K.; Tsai, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 3635–3638. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(98)00653-4 |

| 34. | Bienaymé, H.; Bouzid, K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2234–2237. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2234::aid-anie2234>3.3.co;2-i |

| 11. | Tang, M.; Yang, X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300738. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202300738 |

| 12. | Luo, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 5307–5322. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5c00479 |

| 35. | Hong, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr6135. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adr6135 |

| 8. | Tanaka, K.; Morita, F. J. Synth. Org. Chem., Jpn. 2022, 80, 1019–1027. doi:10.5059/yukigoseikyokaishi.80.1019 |

| 9. | Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.-G.; Shi, F. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 3077–3111. doi:10.1016/j.checat.2022.10.011 |

| 10. | Huang, Q.; Tang, Y.-P.; Zhang, C.-G.; Wang, Z.; Dai, L. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 16256–16265. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c05345 |

| 30. | Luo, Y.; Cheng, S.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Gan, C.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. CCS Chem. 2022, 4, 2897–2905. doi:10.31635/ccschem.021.202101486 |

| 5. | López, R.; Palomo, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202113504. doi:10.1002/anie.202113504 |

| 6. | Laws, D.; Poff, C. D.; Heyboer, E. M.; Blakey, S. B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 6003–6030. doi:10.1039/d3cs00325f |

| 7. | Yang, G.; Wang, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202412805. doi:10.1002/anie.202412805 |

| 31. | Yu, T.; Li, Z.-Q.; Li, J.; Cheng, S.; Xu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhong, Y.-W.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 13034–13041. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c04461 |

| 24. | van Berkel, S. S.; Bögels, B. G. M.; Wijdeven, M. A.; Westermann, B.; Rutjes, F. P. J. T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 3543–3559. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201200030 |

| 25. | Wang, Q.; Wang, D.-X.; Wang, M.-X.; Zhu, J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1290–1300. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00105 |

| 26. | Luo, J.; Chen, G.-S.; Chen, S.-J.; Li, Z.-D.; Liu, Y.-L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 6598–6619. doi:10.1002/chem.202003224 |

| 28. | Teng, F.; Yu, T.; Peng, Y.; Hu, W.; Hu, H.; He, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhu, Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2722–2728. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c00640 |

| 56. | Wang, W.-T.; Zhang, S.; Lin, W.; Luo, Z.-H.; Hu, D.; Huang, F.; Bai, R.; Lan, Y.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 3308–3319. doi:10.1039/d4qo00294f |

| 21. | Gulevich, A. V.; Zhdanko, A. G.; Orru, R. V. A.; Nenajdenko, V. G. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5235–5331. doi:10.1021/cr900411f |

| 22. | Boyarskiy, V. P.; Bokach, N. A.; Luzyanin, K. V.; Kukushkin, V. Y. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2698–2779. doi:10.1021/cr500380d |

| 23. | Giustiniano, M.; Basso, A.; Mercalli, V.; Massarotti, A.; Novellino, E.; Tron, G. C.; Zhu, J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1295–1357. doi:10.1039/c6cs00444j |

| 29. | Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Luo, S. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 201–210. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c06720 |

| 57. | Huang, F.; Tao, L.-F.; Liu, J.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 4487–4490. doi:10.1039/d3cc00708a |

| 19. | Kaur, T.; Wadhwa, P.; Bagchi, S.; Sharma, A. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 6958–6976. doi:10.1039/c6cc01562j |

| 20. | Doraghi, F.; Baghershahi, P.; Gilaninezhad, F.; Darban, N. M. Z.; Dastyafteh, N.; Noori, M.; Mahdavi, M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2025, 367, e202400994. doi:10.1002/adsc.202400994 |

| 54. | Tao, L.-F.; Huang, F.; Zhao, X.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101697. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101697 |

| 16. | Qiu, G.; Ding, Q.; Wu, J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5257–5269. doi:10.1039/c3cs35507a |

| 17. | Song, B.; Xu, B. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1103–1123. doi:10.1039/c6cs00384b |

| 18. | Collet, J. W.; Roose, T. R.; Ruijter, E.; Maes, B. U. W.; Orru, R. V. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 540–558. doi:10.1002/anie.201905838 |

| 27. | Luo, S.; Xiong, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Q. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1837–1840. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00348 |

| 55. | Zhang, S.; Luo, Z.-H.; Wang, W.-T.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4645–4649. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01761 |

| 39. | Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Shao, H.; Ma, X. Molecules 2022, 27, 8517. doi:10.3390/molecules27238517 |

| 40. | Sun, H.-R.; Sharif, A.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202300183. doi:10.1002/chem.202300183 |

| 36. | Kamijo, S.; Kanazawa, C.; Yamamoto, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9260–9266. doi:10.1021/ja051875m |

| 37. | Larionov, O. V.; de Meijere, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5664–5667. doi:10.1002/anie.200502140 |

| 38. | Zheng, S.-C.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1494–1498. doi:10.1002/anie.201812654 |

| 45. | Bringmann, G.; Breuning, M.; Tasler, S. Synthesis 1999, 525–558. doi:10.1055/s-1999-3435 |

| 49. | Wang, W.-T.; Zhang, S.; Tao, L.-F.; Pan, Z.-Q.; Qian, L.; Liao, J.-Y. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 6292–6295. doi:10.1039/d2cc01625g |

| 46. | Wang, G.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Z. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4507–4521. doi:10.1039/d2qo00946c |

| 47. | Wu, C.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, R.; Dou, X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400402. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202400402 |

| 48. | Qian, L.; Tao, L.-F.; Wang, W.-T.; Jameel, E.; Luo, Z.-H.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, J.-Y. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 5086–5091. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01632 |

| 43. | Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L. Chem. – Asian J. 2020, 15, 2939–2951. doi:10.1002/asia.202000681 |

| 44. | Min, X.-L.; Zhang, X.-L.; Shen, R.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 2280–2292. doi:10.1039/d1qo01699g |

| 45. | Bringmann, G.; Breuning, M.; Tasler, S. Synthesis 1999, 525–558. doi:10.1055/s-1999-3435 |

| 41. | He, X.-L.; Zhao, H.-R.; Song, X.; Jiang, B.; Du, W.; Chen, Y.-C. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 4374–4381. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b00767 |

| 42. | Barton, D. H. R.; Zard, S. Z. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985, 1098–1100. doi:10.1039/c39850001098 |

© 2025 Liao; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.