Abstract

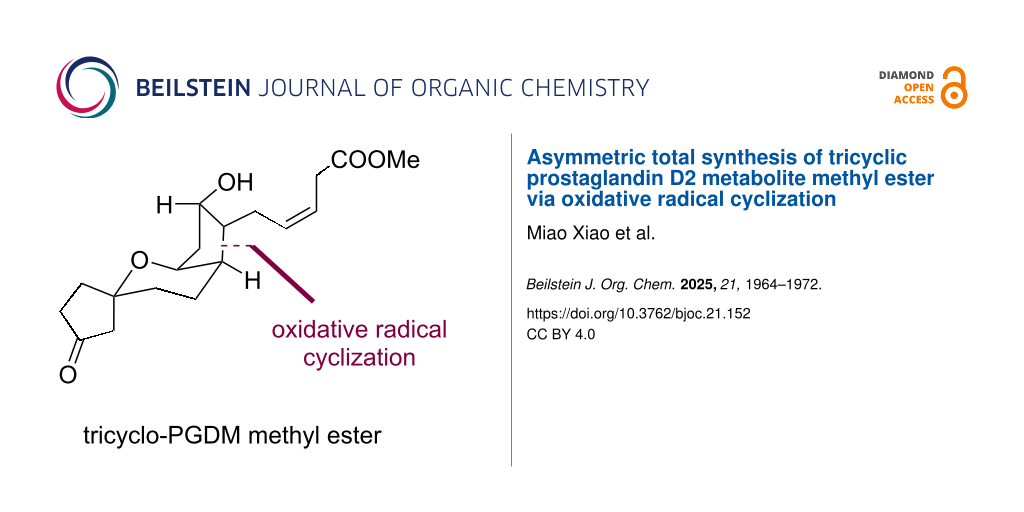

Prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) is a key pathophysiological mediator in many human diseases and biological pathways. Tricyclic prostaglandin D2 metabolite methyl ester (tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester), the major urinary metabolite of PGD2, can be used as a clinical indicator for PGD2 overproduction. However, the limited amount of tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester available has prevented its practical use, and synthesis methods for tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester are required. Based on the utilization of oxidative radical cyclization for the stereoselective construction of the cyclopentanol subunit with three consecutive stereocenters, we describe an asymmetric total synthesis of tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester in 9 steps and 8% overall yield.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Prostaglandins (PGs), a family of hormone-like lipid compounds, are ubiquitous natural products that control many essential biological processes in animals and humans [1-4]. In particular, prostaglandin D2 (PGD2, 3) is a key pathophysiological mediator in a number of human diseases and biological pathways, such as systemic mastocytosis and inflammation. Therefore, the development of methods for sensitive detection of endogenous PGD2 production and its stereoisomers are clinically important [5]. However, PGD2 is rapidly metabolized with a short half-life, making the identification and quantification of its downstream metabolites a promising and reliable diagnostic tool. Tricyclic prostaglandin D2 metabolite methyl ester (tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester, 4), the major urinary metabolite of PGD2, has been used as an indicator for PGD2 overproduction. Roberts and associates established an assay for tricyclic-PGDM measurement using 18O-labelled tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester 8, which is an effective tool in clinical applications [6]. However, the scarcity of metabolite 4 has prevented it from being used more widely, and thus synthesis methods for 4 are required.

Compound 4 contains a cyclopentanol scaffold with stereogenicity at C8, C9, C11, and C12 (Scheme 1A). In addition, 4 is synthetically challenging because of the tricyclic ring system, spiroketal moiety (B, C-ring), and instability arising from dehydration of the hydroxy groups. Prior approaches to (±)-4 have shown the feasibility of accessing this target molecule. Blair [7] and Sulikowski [8] reported the total synthesis of (±)-4 from pentacyclic starting materials 5 and 6, respectively (Scheme 1B). In 2021, Dai reported the total synthesis of (±)-4 from cyclopentanol 7, in which the bicyclic spiroketal moiety and (Z)-3-butenoate side chain were formed via a palladium-catalyzed carbonylative spirolactonization and Z-selective cross-metathesis, respectively [9]. In general, racemic cyclopentanol precursors (A ring system, prepared in 6–9 steps) have been used to form the polyfunctionalized tricyclic frameworks incorporating contiguous stereocenters.

Scheme 1: Representative prostaglandins and general synthetic strategy toward PGDM methyl ester 4.

Scheme 1: Representative prostaglandins and general synthetic strategy toward PGDM methyl ester 4.

In previous syntheses, the efficient construction of the cyclopentanol ring system with the appropriate functional groups in place for attaching the remaining groups is a highly important task for the asymmetric total synthesis of PGs and analogues [10-13]. The groups of Aggarwal [14], Hayashi [15], and Zhang [16] have reported bond-disconnection strategies for the total syntheses of PGs via organocatalysis, and enyne cycloisomerization, respectively. Thus, from a strategic viewpoint, developing alternative synthetic approaches for the stereoselective construction of the highly substituted cyclopentanol core framework in compound 4 may advance the efficient total synthesis of 4 and is required to explore alternative synthetic strategies for PGs and analogues [17].

Biosynthetically, 4 is proposed to arise via a 5-exo-trig biogenetic radical-mediated cyclization (Scheme 1C) [18,19]. Over the past five decades, the Snider oxidative radical reaction has been used as a powerful method for synthesizing complex natural products [20,21]. We envisaged that the A-ring in 4 could be constructed from the alkene-substituted β-keto ester precursor A via a bioinspired oxidative radical cyclization (Scheme 1D).

Herein, we report the full details of our efforts to stereoselectively access the syn-anti-cyclopentanol ring system with three vicinal stereogenic centers at C11, C12, and C8 via the oxidative radical cyclization that led to the asymmetric total synthesis of compound 4.

Results and Discussion

First generation asymmetric total synthesis of tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester

The retrosynthetic analysis of tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester 4 is shown in Scheme 2. We expected to derive 4 from tricyclic substrate 12 via a side-chain installation at C8 [22]. The spiroketal moiety in compound 12 could be obtained from compound 13 via a diastereoselective spiroketalization dictated by the anomeric effect [23] in the tricyclic scaffold. Compound 13 could be produced from olefin 14 via cross-metathesis. The regio- and diastereoselective connection of C8 and C12 in compound 14 could be realized through a transition-metal-mediated oxidative radical cyclization through TS-1 from β-keto ester 15 [24]. The β-keto ester 15 was expected to be derived from compounds 16 and 17 via an asymmetric aldol reaction [25].

Scheme 2: Retrosynthetic analysis for the first generation synthesis of PGDM methyl ester 4.

Scheme 2: Retrosynthetic analysis for the first generation synthesis of PGDM methyl ester 4.

The first phase of the synthesis required the efficient preparation of compound 14, for which a transition-metal-mediated oxidative radical cyclization of β-keto ester 15 was initially investigated (Scheme 3). Chan’s diene (16) was subjected to condensation with freshly distilled aldehyde 17 in THF at room temperature, using a catalytic system comprising Ti(OiPr)4/(S)-BINOL complex (2.0 mol %). Subsequent deprotection with pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS) at 0 °C afforded the corresponding alcohol 18 in 89% yield with excellent enantioselectivity (98% ee) [25]. The hydroxy group in 18 was then protected via treatment with TBSCl in the presence of Et3N in CH2Cl2, yielding β-keto ester 15 in 52% yield.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of bicyclic ketal 25.

Scheme 3: Synthesis of bicyclic ketal 25.

With diketone 15 in hand, we subsequently investigated the transition-metal-mediated oxidative radical cyclization for constructing cyclopentanone 14. First, we used Mn(OAc)3·2H2O/Cu(OAc)2·H2O [21] as the oxidant system to perform oxidative annulation of β-keto ester 15 in MeCN as solvent. However, only 9% of the desired product 14 was obtained after conducting the reaction at 50 °C for 36 h, and extensive decomposition of the starting material β-keto ester 15 occurred (Table 1, entry 1). Solvent screening of EtOH [26], acetic acid [26], and hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) [27] demonstrated that HFIP afforded optimal results, delivering cyclopentanone 14 in 63% yield as a single diastereomer (Table 1, entry 4). To explain this diastereoselectivity, we hypothesize that the C–O bond, which occupies an axial position in the proposed transition state TS-1, could avert an additional hyperconjugative interaction (σ*C-O/π) that renders the reacting C=C bond electron-deficient [28], thereby lowering the energy barrier for electrophilic radical addition. Increasing the reaction temperature to 70 °C proved detrimental, yielding only trace amounts of product 14 (Table 1, entry 5). Finally, replacing Mn(OAc)3·2H2O/Cu(OAc)2·H2O with other oxidants, such as ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN) [29,30] and Fe(ClO4)3·9H2O [31], failed to afford desired product 14 (Table 1, entries 6 and 7).

Table 1: Optimization of conditions to convert diketone 15 into cyclopentanone 14.a

|

|

||||

| entry | oxidant | solvent | temp. (°C) | yield (%) |

| 1 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (2.2 equiv), Cu(OAc)2·H2O (1.1 equiv) | MeCN | 50 | 9 |

| 2 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (2.2 equiv), Cu(OAc)2·H2O (1.1 equiv) | EtOH | 50 | 0 |

| 3 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (2.2 equiv), Cu(OAc)2·H2O (1.1 equiv) | AcOH | 50 | 12 |

| 4 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (2.2 equiv), Cu(OAc)2·H2O (1.1 equiv) | HFIP | 50 | 63 |

| 5 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (2.2 equiv), Cu(OAc)2·H2O (1.1 equiv) | HFIP | 70 | trace |

| 6 | Fe(ClO4)3·9H2O (2.2 equiv) | HFIP | 50 | 0 |

| 7 | CAN (2.2 equiv) | HFIP | 50 | 0 |

aStep c in Scheme 3.

To explore the synthesis of fully functionalized tricyclic core scaffold 12, methods for incorporating the side chain at C14 and for the stereocontrolled introduction of the allyl moiety at C8 were developed. A straightforward transformation was designed involving a cross-metathesis of the C13–C14 double bond and a palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation [32] as the key steps.

With 14 in hand, we investigated the feasibility of cross-metathesis of the C13–C14 double bond. Initially, compounds 14 and 20 were evaluated for the cross-metathesis of the olefin moiety in 14. No reaction occurred and the desired product was not detected (not shown), presumably because of the steric hindrance from the TBS group. Following the removal of the silyl group, cyclopentanol 19 underwent the cross-metathesis reaction smoothly in the presence of the Hoveyda–Grubbs second-generation catalyst to afford the enone 13 in 63% yield with the desired trans-configuration. Enone 13 was then subjected to the Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenation to give the thermodynamically favored bicyclic hemiketal 21 in 92% yield as an inseparable mixture of diastereomers at C-15 in a ratio of 1.0/1.1 (1H NMR analysis).

Having established a route to the bicyclic hemiketal 21, we investigated the stereoselective introduction of an allyl moiety at C8 for the synthesis of compound 25 according to the strategy in Scheme 3. Treatment of 21 with allyl alcohol and triphenylphosphine afforded transesterification product 22 in 21% yield [33], accompanied by unidentified decarboxylation by-products. A variety of standard conditions failed to promote the palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation of allylic β-ketocarboxylate intermediate 22 (see Supporting Information File 1 for the details). Reasoning that the preferential coordination of the palladium catalyst with the hydroxy group at C15 and the carbonyl group at C18 in compound 22 may have deactivated the palladium catalyst [34], we protected the hydroxy group. Compound 22 was treated with p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TSA) in EtOH at room temperature to afford ketal 24 in 83% yield as a single diastereomer. Subsequently, palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation delivered compound 25 in 89% yield.

The efficiency of our first-generation strategy for asymmetric synthesis of 4 was unsatisfactory because it required nine steps to prepare bicyclic intermediate 25 with an overall yield of just 2.0%. This low efficiency prompted us to develop a more streamlined synthetic route for target compound 4.

Second generation asymmetric total synthesis of tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester

Although the efficiency of the first-generation asymmetric total synthesis strategy was limited, the development of synthetic methods during this work, particularly the transition-metal-mediated oxidative radical cyclization for stereoselective assembly of the cyclopentanol scaffold bearing the C8, C11, and C12 contiguous stereogenic centers, provided important insights that influenced the design of our second-generation total synthesis. Compared with the Snider-type radical cyclization using stoichiometric amounts of metal oxidants, visible-light-induced photoredox-catalyzed radical cyclization strategies have emerged as an effective synthetic route for the stereocontrolled construction of diverse, highly functionalized bioactive and pharmaceutical molecules [35-37].

The herein adopted synthetic strategy, employing photoredox-catalyzed radical cyclization, is illustrated in Scheme 4. Compound 4 was expected to be derived from tricyclic substrate 26 via a Z-selective cross-metathesis [9]. The allyl group in compound 26 could be installed in β-keto ester 21 via sequential transesterification [33] and palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation [32]. The regio- and diastereoselective connection of C8 and C12 in compound 21 could be realized through a photoredox-catalyzed radical cyclization of unactivated alkene-substituted β-ketoester 27. This reaction was expected to involve a 5-exo-trig radical cyclization via transition state TS-3 [38], in which the diastereoselectivity could be controlled by the stereoelectronic effect of the axial hydroxy group at C11 (Scheme 4) [28].

Scheme 4: Retrosynthetic analysis for the second-generation synthesis of tricyclic PGDM methyl ester 4.

Scheme 4: Retrosynthetic analysis for the second-generation synthesis of tricyclic PGDM methyl ester 4.

First, β-keto ester 21 was synthesized (Scheme 5). Cross-metathesis of allylic alcohol 18 and olefin 28 with the assistance of the Hoveyda–Grubbs second-generation catalyst delivered the desired product 27 in 68% yield. Having accessed the β-keto ester 27, the photoredox-catalyzed oxidative radical cyclization of compound 27 was established on a 0.8 g scale, yielding compound 21 in 80% yield, as an inseparable mixture of diastereomers at C-15, the precursor for palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation. The proposed mechanism to 21 involved the formation of an electron-deficient, resonance-stabilized radical species, followed by intramolecular alkylation of the unactivated alkene to generate radical 29 via a diastereoselective 5-exo-trig cyclization step. Radical intermediate 29 was trapped by 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenethiol (TRIPSH) through a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) process to afford intermediate 30 [39], which then cyclized to yield product 21.

Scheme 5: Asymmetric total synthesis of tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester 4.

Scheme 5: Asymmetric total synthesis of tricyclic-PGDM methyl ester 4.

To install the allyl group at C8 with the desired stereochemistry, we treated compound 21 with p-TSA in EtOH at room temperature, and ketal 31 was obtained in 87% yield as a single diastereomer. Subsequently, one-pot transesterification and palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation delivered compound 25 in 72% yield.

Next, we expected that we could perform a chemo- and diastereoselective reduction of the ketone to introduce the hydroxy group at C9 in a single step. However, the diastereoselective reduction of the ketone in 25 was challenging because the ketone was embedded in the concave face, which was more sterically hindered than the convex face. Common reductants, such as NaBH4, DIBAL-H, and LiAlH(Ot-Bu)3, provided product 32 with the opposite stereochemistry at C9. Therefore, alcohol 32 was subjected to a one-pot Mitsunobu reaction, hydrolyzation, and spirolactonization to give the corresponding alcohol 26 with inversed configuration at C9. Finally, terminal alkene 26 was transformed by Dai’s Ru-catalyzed Z-selective cross-metathesis with 33 [9,40] to provide compound 4 in 8% overall yield over 9 steps starting from the readily available compound 16 [41].

Conclusion

In conclusion, we developed a synthetic strategy using a radical Csp3–H cyclization, including Snider oxidative radical cyclization and photoredox-catalyzed radical cyclization, to construct cyclopentanols with three contiguous stereogenic centers in compound 4. Our total synthesis also features an efficient cross-metathesis reaction to produce photoredox-catalyzed radical cyclization reaction precursor 27, a one-pot transesterification and palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation to install the side chain at C8, and a diastereoselective spirolactonization to generate the spiroketal moiety in 26. This total synthesis is promising for divergent total syntheses of other PGs and structurally related pharmaceutical derivatives.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, characterization data and copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 5.3 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Gibson, K. H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1977, 6, 489–510. doi:10.1039/cs9770600489

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Curtis-Prior, P. B. Prostaglandins: Biology and Chemistry of Prostaglandins and Related Eicosanoids; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 1988.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Funk, C. D. Science 2001, 294, 1871–1875. doi:10.1126/science.294.5548.1871

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dams, I.; Wasyluk, J.; Prost, M.; Kutner, A. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators 2013, 104–105, 109–121. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2013.01.001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liston, T. E.; Roberts, L. J., II. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 13172–13180. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(17)38853-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morrow, J. D.; Prakash, C.; Awad, J. A.; Duckworth, T. A.; Zackert, W. E.; Blair, I. A.; Oates, J. A.; Jackson Roberts, L., II. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 193, 142–148. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(91)90054-w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prakash, C.; Saleh, S.; Roberts, L. J.; Blair, I. A.; Taber, D. F. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1988, 2821–2826. doi:10.1039/p19880002821

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kimbrough, J. R.; Austin, Z.; Milne, G. L.; Sulikowski, G. A. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 10048–10051. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03983

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sims, H. S.; de Andrade Horn, P.; Isshiki, R.; Lim, M.; Xu, Y.; Grubbs, R. H.; Dai, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115633. doi:10.1002/anie.202115633

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Collins, P. W.; Djuric, S. W. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 1533–1564. doi:10.1021/cr00020a007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Das, S.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Yadav, J. S.; Grée, R. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3286–3337. doi:10.1021/cr068365a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Peng, H.; Chen, F.-E. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 6281–6301. doi:10.1039/c7ob01341h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Corey, E. J.; Weinshenker, N. M.; Schaaf, T. K.; Huber, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 5675–5677. doi:10.1021/ja01048a062

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Coulthard, G.; Erb, W.; Aggarwal, V. K. Nature 2012, 489, 278–281. doi:10.1038/nature11411

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hayashi, Y.; Umemiya, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3450–3452. doi:10.1002/anie.201209380

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, F.; Zeng, J.; Gao, M.; Wang, L.; Chen, G.-Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 692–697. doi:10.1038/s41557-021-00706-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ungrin, M. D.; Carrière, M.-C.; Denis, D.; Lamontagne, S.; Sawyer, N.; Stocco, R.; Tremblay, N.; Metters, K. M.; Abramovitz, M. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 1446–1456. doi:10.1016/s0026-895x(24)12272-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sih, C. J.; Ambrus, G.; Foss, P.; Lai, C. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 3685–3687. doi:10.1021/ja01041a065

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jahn, U.; Galano, J.-M.; Durand, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5894–5955. doi:10.1002/anie.200705122

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Snider, B. B.; Mohan, R.; Kates, S. A. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 3659–3661. doi:10.1021/jo00219a054

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Snider, B. B. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 339–364. doi:10.1021/cr950026m

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Šmit, B.; Rodić, M.; Pavlović, R. Z. Synthesis 2016, 48, 387–393. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1561285

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aho, J. E.; Pihko, P. M.; Rissa, T. K. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 4406–4440. doi:10.1021/cr050559n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Snider, B. B.; Patricia, J. J. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 38–46. doi:10.1021/jo00262a016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, Q.; Yu, J.; Han, F.; Hu, J.; Chen, W.; Yang, L. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 156–158. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.01.008

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Snider, B. B.; Merritt, J. E.; Dombroski, M. A.; Buckman, B. O. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 5544–5553. doi:10.1021/jo00019a014

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Motiwala, H. F.; Armaly, A. M.; Cacioppo, J. G.; Coombs, T. C.; Koehn, K. R. K.; Norwood, V. M., IV; Aubé, J. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 12544–12747. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00749

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chamberlin, A. R.; Mulholland, R. L., Jr.; Kahn, S. D.; Hehre, W. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 672–677. doi:10.1021/ja00237a006

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nair, V.; Deepthi, A. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1862–1891. doi:10.1021/cr068408n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nair, V.; Mathew, J.; Prabhakaran, J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997, 26, 127–132. doi:10.1039/cs9972600127

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Citterio, A.; Cerati, A.; Sebastiano, R.; Finzi, C.; Santi, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 1289–1292. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)72739-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tsuda, T.; Chujo, Y.; Nishi, S.; Tawara, K.; Saegusa, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 6381–6384. doi:10.1021/ja00540a053

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yadav, J. S.; Reddy, B. V. S.; Krishna, A. D.; Reddy, C. S.; Narsaiah, A. V. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2007, 261, 93–97. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2006.07.060

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Strassfeld, D. A.; Chen, C.-Y.; Park, H. S.; Phan, D. Q.; Yu, J.-Q. Nature 2023, 622, 80–86. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06485-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Romero, K. J.; Galliher, M. S.; Pratt, D. A.; Stephenson, C. R. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7851–7866. doi:10.1039/c8cs00379c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pitre, S. P.; Weires, N. A.; Overman, L. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2800–2813. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b11790

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pitre, S. P.; Overman, L. E. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1717–1751. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00247

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Forbes, K. C.; Crooke, A. M.; Lee, Y.; Kawada, M.; Shamskhou, K. M.; Zhang, R. A.; Cannon, J. S. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 3498–3510. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c03055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dénès, F.; Pichowicz, M.; Povie, G.; Renaud, P. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2587–2693. doi:10.1021/cr400441m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Quigley, B. L.; Grubbs, R. H. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 501–506. doi:10.1039/c3sc52806e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiao, M.; Shang, Q.; Pu, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J. JACS Au 2025, 5, 1367–1375. doi:10.1021/jacsau.4c01268

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 34. | Strassfeld, D. A.; Chen, C.-Y.; Park, H. S.; Phan, D. Q.; Yu, J.-Q. Nature 2023, 622, 80–86. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06485-8 |

| 35. | Romero, K. J.; Galliher, M. S.; Pratt, D. A.; Stephenson, C. R. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7851–7866. doi:10.1039/c8cs00379c |

| 36. | Pitre, S. P.; Weires, N. A.; Overman, L. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2800–2813. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b11790 |

| 37. | Pitre, S. P.; Overman, L. E. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1717–1751. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00247 |

| 9. | Sims, H. S.; de Andrade Horn, P.; Isshiki, R.; Lim, M.; Xu, Y.; Grubbs, R. H.; Dai, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115633. doi:10.1002/anie.202115633 |

| 1. | Gibson, K. H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1977, 6, 489–510. doi:10.1039/cs9770600489 |

| 2. | Curtis-Prior, P. B. Prostaglandins: Biology and Chemistry of Prostaglandins and Related Eicosanoids; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 1988. |

| 3. | Funk, C. D. Science 2001, 294, 1871–1875. doi:10.1126/science.294.5548.1871 |

| 4. | Dams, I.; Wasyluk, J.; Prost, M.; Kutner, A. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators 2013, 104–105, 109–121. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2013.01.001 |

| 8. | Kimbrough, J. R.; Austin, Z.; Milne, G. L.; Sulikowski, G. A. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 10048–10051. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03983 |

| 23. | Aho, J. E.; Pihko, P. M.; Rissa, T. K. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 4406–4440. doi:10.1021/cr050559n |

| 41. | Xiao, M.; Shang, Q.; Pu, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J. JACS Au 2025, 5, 1367–1375. doi:10.1021/jacsau.4c01268 |

| 7. | Prakash, C.; Saleh, S.; Roberts, L. J.; Blair, I. A.; Taber, D. F. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1988, 2821–2826. doi:10.1039/p19880002821 |

| 24. | Snider, B. B.; Patricia, J. J. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 38–46. doi:10.1021/jo00262a016 |

| 6. | Morrow, J. D.; Prakash, C.; Awad, J. A.; Duckworth, T. A.; Zackert, W. E.; Blair, I. A.; Oates, J. A.; Jackson Roberts, L., II. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 193, 142–148. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(91)90054-w |

| 20. | Snider, B. B.; Mohan, R.; Kates, S. A. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 3659–3661. doi:10.1021/jo00219a054 |

| 21. | Snider, B. B. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 339–364. doi:10.1021/cr950026m |

| 39. | Dénès, F.; Pichowicz, M.; Povie, G.; Renaud, P. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2587–2693. doi:10.1021/cr400441m |

| 5. | Liston, T. E.; Roberts, L. J., II. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 13172–13180. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(17)38853-1 |

| 22. | Šmit, B.; Rodić, M.; Pavlović, R. Z. Synthesis 2016, 48, 387–393. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1561285 |

| 9. | Sims, H. S.; de Andrade Horn, P.; Isshiki, R.; Lim, M.; Xu, Y.; Grubbs, R. H.; Dai, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115633. doi:10.1002/anie.202115633 |

| 40. | Quigley, B. L.; Grubbs, R. H. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 501–506. doi:10.1039/c3sc52806e |

| 15. | Hayashi, Y.; Umemiya, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3450–3452. doi:10.1002/anie.201209380 |

| 17. | Ungrin, M. D.; Carrière, M.-C.; Denis, D.; Lamontagne, S.; Sawyer, N.; Stocco, R.; Tremblay, N.; Metters, K. M.; Abramovitz, M. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 1446–1456. doi:10.1016/s0026-895x(24)12272-9 |

| 38. | Forbes, K. C.; Crooke, A. M.; Lee, Y.; Kawada, M.; Shamskhou, K. M.; Zhang, R. A.; Cannon, J. S. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 3498–3510. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c03055 |

| 14. | Coulthard, G.; Erb, W.; Aggarwal, V. K. Nature 2012, 489, 278–281. doi:10.1038/nature11411 |

| 18. | Sih, C. J.; Ambrus, G.; Foss, P.; Lai, C. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 3685–3687. doi:10.1021/ja01041a065 |

| 19. | Jahn, U.; Galano, J.-M.; Durand, T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5894–5955. doi:10.1002/anie.200705122 |

| 28. | Chamberlin, A. R.; Mulholland, R. L., Jr.; Kahn, S. D.; Hehre, W. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 672–677. doi:10.1021/ja00237a006 |

| 10. | Collins, P. W.; Djuric, S. W. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 1533–1564. doi:10.1021/cr00020a007 |

| 11. | Das, S.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Yadav, J. S.; Grée, R. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3286–3337. doi:10.1021/cr068365a |

| 12. | Peng, H.; Chen, F.-E. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 6281–6301. doi:10.1039/c7ob01341h |

| 13. | Corey, E. J.; Weinshenker, N. M.; Schaaf, T. K.; Huber, W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 5675–5677. doi:10.1021/ja01048a062 |

| 33. | Yadav, J. S.; Reddy, B. V. S.; Krishna, A. D.; Reddy, C. S.; Narsaiah, A. V. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2007, 261, 93–97. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2006.07.060 |

| 9. | Sims, H. S.; de Andrade Horn, P.; Isshiki, R.; Lim, M.; Xu, Y.; Grubbs, R. H.; Dai, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115633. doi:10.1002/anie.202115633 |

| 16. | Zhang, F.; Zeng, J.; Gao, M.; Wang, L.; Chen, G.-Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 692–697. doi:10.1038/s41557-021-00706-1 |

| 32. | Tsuda, T.; Chujo, Y.; Nishi, S.; Tawara, K.; Saegusa, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 6381–6384. doi:10.1021/ja00540a053 |

| 25. | Xu, Q.; Yu, J.; Han, F.; Hu, J.; Chen, W.; Yang, L. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 156–158. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.01.008 |

| 25. | Xu, Q.; Yu, J.; Han, F.; Hu, J.; Chen, W.; Yang, L. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 156–158. doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.01.008 |

| 32. | Tsuda, T.; Chujo, Y.; Nishi, S.; Tawara, K.; Saegusa, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 6381–6384. doi:10.1021/ja00540a053 |

| 33. | Yadav, J. S.; Reddy, B. V. S.; Krishna, A. D.; Reddy, C. S.; Narsaiah, A. V. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2007, 261, 93–97. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2006.07.060 |

| 29. | Nair, V.; Deepthi, A. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1862–1891. doi:10.1021/cr068408n |

| 30. | Nair, V.; Mathew, J.; Prabhakaran, J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997, 26, 127–132. doi:10.1039/cs9972600127 |

| 31. | Citterio, A.; Cerati, A.; Sebastiano, R.; Finzi, C.; Santi, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 1289–1292. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)72739-0 |

| 27. | Motiwala, H. F.; Armaly, A. M.; Cacioppo, J. G.; Coombs, T. C.; Koehn, K. R. K.; Norwood, V. M., IV; Aubé, J. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 12544–12747. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00749 |

| 28. | Chamberlin, A. R.; Mulholland, R. L., Jr.; Kahn, S. D.; Hehre, W. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 672–677. doi:10.1021/ja00237a006 |

| 26. | Snider, B. B.; Merritt, J. E.; Dombroski, M. A.; Buckman, B. O. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 5544–5553. doi:10.1021/jo00019a014 |

| 26. | Snider, B. B.; Merritt, J. E.; Dombroski, M. A.; Buckman, B. O. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 5544–5553. doi:10.1021/jo00019a014 |

© 2025 Xiao et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.