Abstract

Illicium sesquiterpenes are a large class of highly oxygenated and sterically congested sesquiterpenoids isolated from the genus Illicium. Illisimonin A stands out as one of the most structurally intricate members of this family, featuring a novel bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane carbon framework designated as the “illisimonane” skeleton. This core ring system is further embellished by additional bridging via a γ-lactone and a γ-lactol ring, resulting in a caged pentacyclic scaffold with a 5/5/5/5/5 ring arrangement. The compound demonstrates neuroprotective activity by mitigating oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced cell injury in SH-SY5Y cells. Since its isolation in 2017, illisimonin A has garnered significant interest from the synthetic chemistry community. To date, five research groups have accomplished the total synthesis of illisimonin A. This review offers a comprehensive overview of its isolation, proposed biosynthetic pathway and the synthetic strategies employed in its total synthesis.

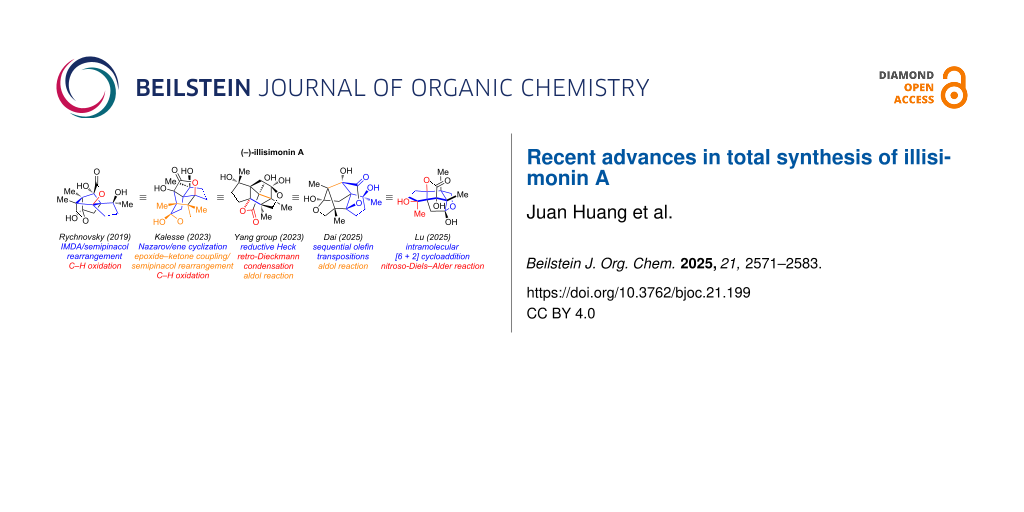

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The genus Illicium, the sole member of the family Illiciaceae, is a rich source of sesquiterpenoid natural products. To date, a wide variety of sesquiterpenes have been isolated from this genus, among which Illicium sesquiterpenes represent a prominent group. Since the first isolation of anisatin in 1952 [1], more than 100 Illicium sesquiterpenes have been isolated from over 40 species of Illicium [2]. Based on their carbon skeletons, they can be classified into the following types: allo-cedrane, anislactone, seco-prezizaane and illisimonane (Figure 1). The illismonane-type is the most recent identified. The seco-prezizaane-type can be further divided into six subtypes according to their lactone patterns, namely anisatin-subtype, pseudoanisatin-subtype, pseudomajucin-subtype, cycloparvifloralone-subtype, majucin-subtype, and miwanensin-subtype (Figure 1). The seminal work by the Fukuyama group demonstrated that some of these natural products exhibit potent neurite outgrowth-promoting activity in primary cultured rat cortical neurons, which has attracted considerable interest from synthetic chemists. Although the intricate structures of this family have posed significant challenges to chemical synthesis, more than 30 total syntheses of Illicium sesquiterpenes have been reported until now [3-25].

Figure 1: The categorization of Illicium sesquiterpenes and representative natural products.

Figure 1: The categorization of Illicium sesquiterpenes and representative natural products.

In 2017, Yu and co-workers isolated a new Illicium sesquiterpene, namely illisimonin A, from the fruits of Illicium simonsii [26]. Unlike other Illicium sesquiterpenes, illisimonin A features an unprecedented bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane carbon framework that incorporates a highly strained trans-pentalene subunit. This carbon ring system is further bridged with a γ-lactone and a γ-lactol ring, forming a caged pentacyclic scaffold with a 5/5/5/5/5 ring arrangement. Illisimonin A was thus classified as an illisimonane-type Illicium sesquiterpene, and its carbon skeleton was designated as “illisimonane skeleton”. The absolute configuration of (−)-illisimonin A was determined to be 1R,4R,5R,6R,7S,9S,10S by comparing the calculated electronic circular dichroism (EDC) spectrum with experimental CD data (Figure 2). Biological evaluation revealed that illisimonin A exhibits neuroprotective effects against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced cell injury in SH-SY5Y cells, suggesting its potential as a lead compound for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Figure 2: The original assigned (−)-illisimonin A, revised (−)-illisimonin A, and their different draws.

Figure 2: The original assigned (−)-illisimonin A, revised (−)-illisimonin A, and their different draws.

The possible biosynthetic pathway of illisimonin A was also proposed by Yu and co-workers, as illustrated in Scheme 1. The proposed biosynthetic pathway clarifies the relationship between illisimonin A and other Illicium sesquiterpenes. Allo-cedrane-type, seco-prezizaane-type and illismonane-type Illicium sesquiterpenes are all biosynthesized from farnesyl diphosphate (2) through a series of cationic cyclizations and migrations. The 5/6/6 tricarbocyclic allo-cedrane framework 6 serves as the key biogenetic intermediate for both the seco-prezizaane and illismonane skeletons. The conversion of the allo-cedrane skeleton to the illismonane skeleton was hypothesized to proceed via a 1,2-alkyl migration of intermediate 9 to 10. However, subsequent density functional theory (DFT) calculations by the Tantillo group on rearrangements of potential biosynthetic precursors revealed that structure 10 corresponds to a transition state rather than a stable intermediate of the 1,2-alkyl migration [27]. Their study further indicated that only certain precursors with certain specific oxidation patterns are competent to undergo this rearrangement.

Scheme 1: Proposed biosynthetic pathway of illisimonin A by Yu et al.

Scheme 1: Proposed biosynthetic pathway of illisimonin A by Yu et al.

The same as other Illicium sesquiterpenes, the highly oxgenated and strained skeleton of illisimonin A has posed a significant challenge to synthetic chemists. To date, the research groups of Rychnovsky [28], Kalesse [29], Yang [30], Dai [31] and Lu [32] have achieved the total synthesis of this molecule. Notable, Rychnovsky and co-workers revised the absolute configuration of (−)-illisimonin A to 1S,4S,5S,6S,7R,9R,10R. This review summarizes the reported synthetic routes toward illisimonin A, including uncompleted approaches.

Review

Rychnovsky’s synthesis and the absolute configuration revision of (−)-illisimonin A

In 2019, Rychnovsky’s group reported the first total synthesis of illisimonin A [28]. Recognizing that the strained trans-pentalene moiety in the molecule is challenging to construct directly, the team adopted a strategy involving rearrangement from the more accessible cis-pentalene isomer. They first assembled the cis-pentalene core through an elegant intramolecular Diels–Alder (IMDA) reaction. Subsequently, the conversion from cis to trans-pentalene was achieved via a semipinacol rearrangement. Finally, a White–Chen C–H oxidation [33-35] was employed to install the lactone ring, thereby completing the synthesis.

The synthesis began with commercially available compound 19 and known compound 20 (Scheme 2). These were joined via an intermolecular aldol reaction to give adduct 21, obtained as a 1.7:1 mixture of diastereomers after protection of one of the carbonyl groups in 19 as enol ether with BOMCl. A silyl-tethered intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction of the in situ generated 22 constructed the tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane core bearing a cis-pentalene unit, yielding compound 23, which was subsequently subjected to a one-pot desilylation to afford 24. Reduction of both the ester and ketone functionalities in 24, followed by selective protection of the primary alcohol and re-oxidation of the secondary alcohol to ketone, furnished compound 25 in three steps. The ketone in 25 was then converted to vinyl iodide 26 via hydrazine formation followed by iodination using Barton’s method. Subsequent Bouvealt aldehyde synthesis and in situ reduction delivered allylic alcohol 27. Epoxidation of 27 with m-CPBA afforded the rearrangement precursor 28. Protonic acid-promoted semipinacol rearrangement of 28 enabled the rearrangement of cis-pentalene to trans-pentalene, delivering intermediate 29, which possesses the same carbon skeleton as the natural product. Further oxidation of the primary alcohol to a carboxylic acid, accompanied by TBS deprotection, afforded hemiketal 30. Finally, a White−Chen C–H oxidation [33-35] of 30 installed the lactone, completing the synthesis of racemic illisimonin A (1).

Scheme 2: Rychnovsky’s racemic synthesis of illisimonin A (1).

Scheme 2: Rychnovsky’s racemic synthesis of illisimonin A (1).

Noting that the C1 configuration of illisimonin A was opposite to that of other Illicium sesquiterpenes, Rychnovsky’s group sought to confirm the absolute configuration of the natural product. They resolved racemic intermediate 27 by derivatization with (S)-1-(1-naphthyl)ethyl isocyanate, followed by separation of the resulting diastereomers via silica gel chromatography (Scheme 3). By converting diastereomer 32 to (−)-illisimonin A, the absolute configuration of the natural product was conclusively revised to 1S,4S,5S,6S,7R,9R,10R.

Scheme 3: The absolute configuration revision of (−)-illisimonin A.

Scheme 3: The absolute configuration revision of (−)-illisimonin A.

Kalesse’s asymmetric synthesis of illisimonin A

In 2023, Kalesse and co-workers reported an asymmetric synthetic route to illisimonin A [29]. The Kalesse group also noticed the strained trans-pentalene in illisimonin A. Since there is a spiro substructure hidden inside the natural product’s cage-like ring system, Kalesse’s group chose to construct this architecture first using a tandem Nazarov/ene cyclization [36]. The cis-pentalene was subsequently assembled via a Ti(III)-mediated epoxide–ketone coupling reaction.

Starting from the known enantioenriched compound 33, a nickel-catalyzed hydrocyanation of the terminal alkyne was performed. Subsequent protection of the tertiary alcohol with TESOTf and reduction of the resulting cyanide to an aldehyde afforded compound 34 (Scheme 4). Addition of isopropenyllithium to aldehyde 34, followed by TES deprotection and oxidation of the secondary alcohol, yielded the cyclization precursor 35. A B(C6F5)3-catalyzed tandem Nazarov/ene cyclization of 35 provided the key spirocyclic intermediate 37. The tertiary alcohol was protected in situ with TESOTf to suppress retro-aldol side reactions. Notably, prior TES deprotection of the cyclization precursor was essential, as the TES-protected analogue of 35 failed to deliver the desired spirocycle 38 under the Nazarov cyclization conditions. α-Oxidation of 38 with molecular oxygen afforded 39, which was then converted to 40 via formation of a chloromethyl silyl ether, deprotonation, and intramolecular addition to ketone. Treatment of the silacycle with MeMgCl cleaved the Si–O bond and subsequent intramolecular nucleophilic substitution of the chloride with the adjacent hydroxy group yielded TMS-epoxide 41. Protonic acid-mediated opening of the TMS-epoxide, accompanied by TES deprotection, afforded enal 42. To avoid the chemoselectivity issues in the subsequent allylic oxidation and radical cyclization steps, enal 42 was converted to 43 by reduction of the aldehyde and protection of the resultant diol with Ph2SiCl2. Allylic oxidation of 43 with 44 [37] afforded the enone in 22% yield (63% brsm) or 50% yield after four cycles with recovery of starting material. Selective epoxidation of the isopropenyl group with m-CPBA delivered cyclization precursor 45 as an inseparable mixture of diastereomers (dr = 1:2.1). A Cp2TiCl-mediated cyclization of 45 constructed the tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane core with a cis-pentalene unit. The product was further processed into rearrangement precursor 46 (as an inseparable mixture, dr = 1:1.6) by TBS protection of the primary alcohol and epoxidation of the alkene with m-CPBA. Unlike Rychnovsky’s substrate, epoxy alcohol 46 underwent rearrangement only under Lewis acidic conditions to furnish 47. Selective TES deprotection with HF afforded Rychnovsky’s intermediate 29. (−)-Illisimonin A was obtained in 13% yield over the same 4-step sequence as reported by Rychnovsky’s group. An alternative 4-step endgame starting from 47 was also developed, albeit with a lower overall yield of 3%.

Scheme 4: Kalesse’s asymmetric synthesis of (−)-illisimonin A.

Scheme 4: Kalesse’s asymmetric synthesis of (−)-illisimonin A.

Yang’s bioinspired synthesis of illisimonin A

In 2023, Yang and co-workers reported a bioinspired divergent synthesis of illisimonin A and merrilactone A, which belonged to illisimonane-type and anislactone-type Illicium sesquiterpenes, respectively [30]. They proposed that a deeper understanding of the biosynthetic pathway of Illicium sesquiterpenes could facilitate a divergent total synthesis of this family of natural products, even among members with distinct carbon skeletons. Since previously proposed biosynthetic pathways lacked key mechanistic details – particularly the critical reactions responsible for skeletal diversity – Yang and co-workers first introduced a comprehensive and detailed biosynthetic pathway for Illicium sesquiterpenes, with the route to illisimonin A depicted in Scheme 5. The transformations from farnesyl diphosphate to the allo-cedryl cation were consistent with earlier reports [2,26], though the configurations of the intermediates were clearly delineated. The authors proposed that dicarbonyl compound 50 serves as the key intermediate diverging to all Illicium sesquiterpenes, with a retro-Dieckmann condensation and aldol reaction identified as the key steps enabling the transformation from the allo-cedrane skeleton to the illisimonane framework.

Scheme 5: Yang group proposed biosynthetic pathway of illisimonin A.

Scheme 5: Yang group proposed biosynthetic pathway of illisimonin A.

Inspired by the proposed biosynthetic pathway, Yang et al. designed a synthetic route as shown in Scheme 6. Starting from the known compound 53, a Tsuji–Trost allylation was employed to introduce another side chain, affording a diene intermediate. A subsequent ring-closing metathesis (RCM) reaction formed the cyclopentene ring, and one pot protection of both carbonyl groups with ethylene glycol provided bis-ketal 55. Notably, due to steric hindrance, only one carbonyl group could be protected prior to the RCM step. Oxidative cleavage of the cyclopentene followed by Pinnick oxidation of the resulting aldehyde to the carboxylic acid and esterification yielded ketoester 56. Dieckmann condensation of 56, esterification of the resulting enolate with 57, and subsequent one-pot partial deketalization afforded carbonate 58. A palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative alkenylation reaction was then carried out across the less hindered face of the six-membered ring to connect C5 and C6. Selective deprotonation and triflation at the C4 carbonyl group provided enol triflate 59. An intramolecular reductive Heck reaction of 59 enabled the transannular connection between C4 and C5, generating key intermediate 60, which possesses the same carbon skeleton as the proposed biosynthetic key intermediate 50 and contains the suitable functional groups for further elaboration. Mukaiyama hydration of 60 introduced a tertiary alcohol at the C4 position, yielding retro-Dieckmann precursor 61. Subsequent retro-Dieckmann condensation under basic conditions, deprotection of the PMP group, and selective ketalization of the C11 carbonyl group afforded compound 62. The C1 methyl group was installed via enol triflate formation followed by a palladium-catalyzed coupling reaction with AlMe3. The carbonyl group at C8, required for the subsequent aldol reaction, was introduced by enolate oxidation followed by Jones oxidation. Hydrolysis of the ketal at C11 afforded ketoester 64. A TBD (1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene)-catalyzed intramolecular aldol reaction connected C6 and C8, assembling the trans-pentalene ring and affording the core carbon framework of illisimonin A. The C1 hydroxy group was initially introduced by a Mukaiyama hydration reaction using O2 as the stoichiometric oxidant; however, illisimonin A was obtained only as a minor product. When O2 was replaced with the nitroaromatic compound 66 [38], the diastereoselectivity was reversed, thereby providing illisimonin A in 57% yield as a single diastereomer. The authors proposed that a hydrogen bond between the nitro group of 66 and the C8 hydroxy group could be responsible for this reversal in selectivity.

Scheme 6: Yang’s bioinspired synthesis of illisimonin A.

Scheme 6: Yang’s bioinspired synthesis of illisimonin A.

Dai’s asymmetric synthesis of (−)-illisimonin A

In 2025, Dai and co-workers accomplished an asymmetric total synthesis of (−)-illisimonin A in 16 steps from (S)-carvone (67) using a pattern-recognition strategy and five sequential olefin transpositions [31].

Starting from (S)-carvone (67), reaction with allyl bromide introduced an allyl group to give 68, which was then converted to the bicyclic compound 69 via a ring-closing metathesis (RCM) reaction followed by one-pot epimerization at the α-position of the carbonyl group (Scheme 7). Chemoselective epoxidation of the enone double bond in 69 yielded epoxide 70. A Wittig reaction of 70 with (methoxymethyl)triphenylphosphonium chloride and t-BuOK generated a methyl enol ether, which was unstable in the presence of the epoxide. During aqueous workup, simultaneous hydrolysis of the enol ether and epoxide ring-opening afforded 71. To install the all-carbon quaternary center at C5, compound 71 was treated with t-BuOK and MeI, enabling the deprotonation of the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde and methylation at C5; this step also facilitated protection of the secondary alcohol. The aldehyde was reduced in the same pot to give 72. Isomerization of the allylic methyl ether to an enol methyl ether was achieved using Crabtree’s catalyst in refluxing THF. Subsequent ketalization with the primary alcohol yielded the bridged ketal 73. A Schenck ene reaction on 73 induced the second olefin isomerization, generating an allylic alcohol that was acetylated in situ to provide 74. An Ireland–Claisen rearrangement facilitated the third olefin transposition, concurrently forming an all-carbon quaternary center at C9 and affording carboxylic acid 75. The fourth olefin transposition was achieved via a palladium-catalyzed oxidative lactonization, yielding 76 with a newly established quaternary center at C1 and isomerization of the double bond to C2=C3. Photocatalyzed isomerization of the C2–C3 double bond in 76 to C3=C4 furnished 77 [39,40]. A Mukaiyama hydration introduced a hydroxy group at C4, accompanied by trans-esterification to give lactone 78. The resulting tertiary alcohol was protected as its benzyl ether to afford 79. A two-step oxidation protocol, analogous to Yang’s method, introduced the C8 carbonyl group, yielding 80. The final ring was closed via an intramolecular aldol reaction following Yang’s conditions [30], assembling the trans-pentalene to give 81. Finally, deprotection of the benzyl ether delivered (−)-illisimonin A (1).

Scheme 7: Dai’s asymmetric synthesis of (–)-illisimonin A.

Scheme 7: Dai’s asymmetric synthesis of (–)-illisimonin A.

Lu’s gram-scale synthesis of illisimonin A

In 2025, the Lu group reported a gram-scale total synthesis of illisimonin A in 15 steps from commercially available starting materials [32]. This synthesis features a pentafulvene-based intramolecular [6 + 2] cycloaddition [41,42] and a nitroso-Diels–Alder reaction [43] as key steps.

The route began with the esterification of pentafulvenol 82 to give β-ketoester 83, which was subsequently converted to the sterically encumbered tricyclic lactone 84 via an intramolecular [6 + 2] cycloaddition (Scheme 8). Attempts to achieve an asymmetric version of the cycloaddition were unsuccessful. Treatment of the lactone with MeMgBr, followed by mesylation and elimination of the resulting hemiacetal, afforded enol ether 85. Reaction of 85 with iodine and BnOH enabled the intermolecular iodoetherification to yield ketal 86. A KF-promoted intramolecular alkylation of the cyclopentadiene moiety then delivered compound 87. To introduce the C4 hydroxy group and C1 functional handle for further elaboration, a nitroso-Diels–Alder reaction of 87 was employed, generating both the kinetic product 88 and the desired thermodynamic product 89. Heating 88 promoted a retro-Diels–Alder/Diels–Alder equilibrium, favoring the more stable isomer 89. Palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation of the 1,2-disubstituted alkene in 89, followed by Mo(CO)6-mediated N–O bond cleavage afforded carbamate 90. The carbamate was converted to a carbonyl group via Boc deprotection with TFA, oxidation of the resulting amine to the oxime with Na2WO4 and H2O2, and subsequent reduction with TiCl3·HCl to give 91. The LaCl3·2LiCl-mediated methyl addition to the carbonyl group installed the tertiary alcohol at C1, yielding intermediate 92. The α-hydroxy lactone was constructed through RuO4-mediated oxidation, forming the pentacyclic core. Finally, debenzylation of the resulting pentacyclic compound under palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation provided (±)-illisimonin A. Notably, the authors were able to obtain 1.8 g of the natural product in a single run.

Scheme 8: Lu’s total synthesis of illisimonin A.

Scheme 8: Lu’s total synthesis of illisimonin A.

The successful total synthesis of illisimonin A by the Lu group was preceded by instructive setbacks, primarily in constructing the trans-fused 5/5 ring system. As depicted in Scheme 9, compound 85 was first transformed into the pentacyclic diene intermediate 93 via a two-step sequence. Subsequent [4 + 2] cycloaddition of 93 with singlet oxygen yielded an unstable endoperoxide adduct 94, which rearranged to diketone 95. A five-step sequence, featuring an intramolecular aldol reaction to assemble the pentacyclic core and the installation of the C1 methyl group, then afforded compound 96. However, subjecting 96 to the singlet oxygen cycloaddition again led to rearrangement, producing diketones 98 and 99. The solution was found by employing a nitroso-Diels–Alder reaction with dienophile 87, which provided a stable adduct and ultimately enabled the completion of the synthesis. This strategic pivot offers a key lesson for handling fragile cycloaddition adducts.

Scheme 9: Initial efforts toward the total synthesis of illisimonin A by the Lu Group.

Scheme 9: Initial efforts toward the total synthesis of illisimonin A by the Lu Group.

Suzuki’s synthetic effort towards illisimonin A

A synthetic study aimed at constructing the tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane core of illisimonin A was reported by Suzuki and co-workers in 2021 [44]. Their work proposed that this core structure could be generated from a highly oxidized allo-cedrane moiety through a tandem retro-Claisen/aldol reaction.

Beginning with compound 100, a 6-step sequence afforded ortho-quinone 101 (Scheme 10). Heating 101 promoted an intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction, affording 102 and 103 in 91% yield with a 1:6 ratio. The major product 103 was selected to investigate the tandem retro-Claisen/aldol reaction. Hydrolysis of the enol methyl ether in 103 under acidic conditions delivered triketone 104. Subsequent treatment of 104 with aqueous NaOH facilitated a retro-Claisen reaction, yielding the intermediate 106, which subsequently underwent an intramolecular aldol reaction to form the five-membered ring. The resulting carboxylic acid was then esterified with TMSCHN2 to furnish ester 107, which possesses the characteristic tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane core of illisimonin A.

Scheme 10: Suzuki’s synthetic effort towards illisimonin A.

Scheme 10: Suzuki’s synthetic effort towards illisimonin A.

Conclusion

Over the past seventy years, ongoing chemical investigations of the Illicium species have led to the discovery of a great number of Illicium sesquiterpenes. The sterically congested and highly oxygenated skeleton of allo-cedrane-type, anislactone-type, and seco-prezizaane-type Illicium sesquiterpenes have attracted significant interest from synthetic chemists, resulting in numerous elegant total syntheses of molecules within this family. The recent identification of illisimonin A has further expanded the structural diversity of Illicium sesquiterpenes. Its tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane core, which contains a strained trans-pentalene subunit, presents new synthetic challenges. A breakthrough in the total synthesis of illisimonin A was achieved by Rychnovsky and co-workers through a rearrangement strategy that also led to the correction of its absolute configuration. Kalesse and co-workers accomplished the first asymmetric total synthesis of (−)-illisimonin A based on strategies involving spiro substructure assembly and rearrangement. Consideration of the biosynthetic pathway of illisimonin A inspired Yang and co-workers to develop a bioinspired synthetic route. Employing a pattern-recognition strategy, Dai and co-workers achieved the second asymmetric total synthesis of (−)-illisimonin A in 16 steps. Lu and co-workers realized the shortest and gram-scale total synthesis of racemic illisimonin A in 15 steps by leveraging a higher-order cycloaddition. Although various synthetic strategies have been developed, only two of them are asymmetric. Designing a more efficient and asymmetric synthetic route remains a worthwhile pursuit.

Funding

Financial Support was provided by the Department of Science and Technology of Gansu Province (22ZD6FA006, 23ZDFA015, 24ZD13FA017 and 24ZDFA003), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22322105 and 22571126), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky-2023-ey01), and the Wen Kui Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data was generated or analyzed in this study.

References

-

Lane, J. F.; Koch, W. T.; Leeds, N. S.; Gorin, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 3211–3215. doi:10.1021/ja01133a002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fukuyama, Y.; Huang, J. M. Chemistry and neurotrophic activity of seco-prezizaane- and anislactone-type sesquiterpenes from Illicium species. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Bioactive Natural Products (Part L), Vol. 32; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2005; pp 395–427. doi:10.1016/s1572-5995(05)80061-4

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Urabe, D.; Inoue, M. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6271–6289. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.06.010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, J.; Lacoske, M. H.; Theodorakis, E. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 956–987. doi:10.1002/anie.201302268

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 36, 439–446. doi:10.6023/cjoc201511054

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Condakes, M. L.; Novaes, L. F. T.; Maimone, T. J. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14843–14852. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02802

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hung, K.; Condakes, M. L.; Novaes, L. F. T.; Harwood, S. J.; Morikawa, T.; Yang, Z.; Maimone, T. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3083–3099. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b12247

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dooley, C. J., III; Rychnovsky, S. D. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 3411–3415. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01207

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cook, S. P.; Polara, A.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 16440–16441. doi:10.1021/ja0670254

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mehta, G.; Maity, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1749–1752. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.02.012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ohtawa, M.; Krambis, M. J.; Cerne, R.; Schkeryantz, J. M.; Witkin, J. M.; Shenvi, R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9637–9644. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04206

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tong, J.; Xia, T.; Wang, B. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 2730–2734. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c00689

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Birman, V. B.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2080–2081. doi:10.1021/ja012495d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Inoue, M.; Sato, T.; Hirama, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10772–10773. doi:10.1021/ja036587+

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meng, Z.; Danishefsky, S. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1511–1513. doi:10.1002/anie.200462509

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Inoue, M.; Sato, T.; Hirama, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4843–4848. doi:10.1002/anie.200601358

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mehta, G.; Singh, S. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 953–955. doi:10.1002/anie.200503618

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, W.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Frontier, A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 498–499. doi:10.1021/ja068150i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, W.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Frontier, A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 300–308. doi:10.1021/ja0761986

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shi, L.; Meyer, K.; Greaney, M. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9250–9253. doi:10.1002/anie.201005156

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, J.; Gao, P.; Yu, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhai, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5897–5899. doi:10.1002/anie.201200378

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, W.; Wang, B. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 16511–16515. doi:10.1002/chem.201804195

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shen, Y.; Li, L.; Xiao, X.; Yang, S.; Hua, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.-w.; Zhang, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3256–3263. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c00525

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huffman, B. J.; Chu, T.; Hanaki, Y.; Wong, J. J.; Chen, S.; Houk, K. N.; Shenvi, R. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202114514. doi:10.1002/anie.202114514

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fu, P.; Liu, T.; Shen, Y.; Lei, X.; Xiao, T.; Chen, P.; Qiu, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 18642–18648. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c06442

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, S.-G.; Li, M.; Lin, M.-B.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.-B.; Qu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.-J.; Wang, R.-B.; Xu, S.; Hou, Q.; Yu, S.-S. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6160–6163. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03050

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

McCulley, C. H.; Tantillo, D. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6060–6065. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b12398

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burns, A. S.; Rychnovsky, S. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13295–13300. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b05065

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Etling, C.; Tedesco, G.; Di Marco, A.; Kalesse, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 7021–7029. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c01262

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gong, X.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306367. doi:10.1002/anie.202306367

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Xu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 17592–17597. doi:10.1021/jacs.5c05409

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Lu, Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 23417–23421. doi:10.1021/jacs.5c07921

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chen, M. S.; White, M. C. Science 2007, 318, 783–787. doi:10.1126/science.1148597

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bigi, M. A.; Reed, S. A.; White, M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9721–9726. doi:10.1021/ja301685r

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

White, M. C.; Zhao, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13988–14009. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b05195

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Etling, C.; Tedesco, G.; Kalesse, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 9257–9262. doi:10.1002/chem.202101041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wilde, N. C.; Isomura, M.; Mendoza, A.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4909–4912. doi:10.1021/ja501782r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bhunia, A.; Bergander, K.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Studer, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 8313–8320. doi:10.1002/anie.202015740

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Occhialini, G.; Palani, V.; Wendlandt, A. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 145–152. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c12043

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Palani, V.; Wendlandt, A. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 20053–20061. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c06935

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, T. C.; Houk, K. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 5308–5309. doi:10.1021/ja00304a065

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hayashi, Y.; Gotoh, H.; Honma, M.; Sankar, K.; Kumar, I.; Ishikawa, H.; Konno, K.; Yui, H.; Tsuzuki, S.; Uchimaru, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20175–20185. doi:10.1021/ja108516b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Carosso, S.; Miller, M. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 7445–7468. doi:10.1039/c4ob01033g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suzuki, T.; Nagahama, R.; Fariz, M. A.; Yukutake, Y.; Ikeuchi, K.; Tanino, K. Organics 2021, 2, 306–312. doi:10.3390/org2030016

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Lane, J. F.; Koch, W. T.; Leeds, N. S.; Gorin, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 3211–3215. doi:10.1021/ja01133a002 |

| 27. | McCulley, C. H.; Tantillo, D. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6060–6065. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b12398 |

| 36. | Etling, C.; Tedesco, G.; Kalesse, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 9257–9262. doi:10.1002/chem.202101041 |

| 26. | Ma, S.-G.; Li, M.; Lin, M.-B.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.-B.; Qu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.-J.; Wang, R.-B.; Xu, S.; Hou, Q.; Yu, S.-S. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6160–6163. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03050 |

| 37. | Wilde, N. C.; Isomura, M.; Mendoza, A.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4909–4912. doi:10.1021/ja501782r |

| 3. | Urabe, D.; Inoue, M. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6271–6289. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.06.010 |

| 4. | Xu, J.; Lacoske, M. H.; Theodorakis, E. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 956–987. doi:10.1002/anie.201302268 |

| 5. | Li, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 36, 439–446. doi:10.6023/cjoc201511054 |

| 6. | Condakes, M. L.; Novaes, L. F. T.; Maimone, T. J. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14843–14852. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02802 |

| 7. | Hung, K.; Condakes, M. L.; Novaes, L. F. T.; Harwood, S. J.; Morikawa, T.; Yang, Z.; Maimone, T. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3083–3099. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b12247 |

| 8. | Dooley, C. J., III; Rychnovsky, S. D. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 3411–3415. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01207 |

| 9. | Cook, S. P.; Polara, A.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 16440–16441. doi:10.1021/ja0670254 |

| 10. | Mehta, G.; Maity, P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1749–1752. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.02.012 |

| 11. | Ohtawa, M.; Krambis, M. J.; Cerne, R.; Schkeryantz, J. M.; Witkin, J. M.; Shenvi, R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9637–9644. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04206 |

| 12. | Tong, J.; Xia, T.; Wang, B. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 2730–2734. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c00689 |

| 13. | Birman, V. B.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2080–2081. doi:10.1021/ja012495d |

| 14. | Inoue, M.; Sato, T.; Hirama, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10772–10773. doi:10.1021/ja036587+ |

| 15. | Meng, Z.; Danishefsky, S. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1511–1513. doi:10.1002/anie.200462509 |

| 16. | Inoue, M.; Sato, T.; Hirama, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4843–4848. doi:10.1002/anie.200601358 |

| 17. | Mehta, G.; Singh, S. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 953–955. doi:10.1002/anie.200503618 |

| 18. | He, W.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Frontier, A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 498–499. doi:10.1021/ja068150i |

| 19. | He, W.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Frontier, A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 300–308. doi:10.1021/ja0761986 |

| 20. | Shi, L.; Meyer, K.; Greaney, M. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9250–9253. doi:10.1002/anie.201005156 |

| 21. | Chen, J.; Gao, P.; Yu, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhai, H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5897–5899. doi:10.1002/anie.201200378 |

| 22. | Liu, W.; Wang, B. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 16511–16515. doi:10.1002/chem.201804195 |

| 23. | Shen, Y.; Li, L.; Xiao, X.; Yang, S.; Hua, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.-w.; Zhang, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3256–3263. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c00525 |

| 24. | Huffman, B. J.; Chu, T.; Hanaki, Y.; Wong, J. J.; Chen, S.; Houk, K. N.; Shenvi, R. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202114514. doi:10.1002/anie.202114514 |

| 25. | Fu, P.; Liu, T.; Shen, Y.; Lei, X.; Xiao, T.; Chen, P.; Qiu, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 18642–18648. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c06442 |

| 33. | Chen, M. S.; White, M. C. Science 2007, 318, 783–787. doi:10.1126/science.1148597 |

| 34. | Bigi, M. A.; Reed, S. A.; White, M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9721–9726. doi:10.1021/ja301685r |

| 35. | White, M. C.; Zhao, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13988–14009. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b05195 |

| 2. | Fukuyama, Y.; Huang, J. M. Chemistry and neurotrophic activity of seco-prezizaane- and anislactone-type sesquiterpenes from Illicium species. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Bioactive Natural Products (Part L), Vol. 32; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2005; pp 395–427. doi:10.1016/s1572-5995(05)80061-4 |

| 29. | Etling, C.; Tedesco, G.; Di Marco, A.; Kalesse, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 7021–7029. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c01262 |

| 31. | Xu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 17592–17597. doi:10.1021/jacs.5c05409 |

| 28. | Burns, A. S.; Rychnovsky, S. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13295–13300. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b05065 |

| 30. | Gong, X.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306367. doi:10.1002/anie.202306367 |

| 33. | Chen, M. S.; White, M. C. Science 2007, 318, 783–787. doi:10.1126/science.1148597 |

| 34. | Bigi, M. A.; Reed, S. A.; White, M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9721–9726. doi:10.1021/ja301685r |

| 35. | White, M. C.; Zhao, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13988–14009. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b05195 |

| 29. | Etling, C.; Tedesco, G.; Di Marco, A.; Kalesse, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 7021–7029. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c01262 |

| 28. | Burns, A. S.; Rychnovsky, S. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13295–13300. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b05065 |

| 32. | Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Lu, Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 23417–23421. doi:10.1021/jacs.5c07921 |

| 38. | Bhunia, A.; Bergander, K.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Studer, A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 8313–8320. doi:10.1002/anie.202015740 |

| 30. | Gong, X.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306367. doi:10.1002/anie.202306367 |

| 2. | Fukuyama, Y.; Huang, J. M. Chemistry and neurotrophic activity of seco-prezizaane- and anislactone-type sesquiterpenes from Illicium species. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Bioactive Natural Products (Part L), Vol. 32; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2005; pp 395–427. doi:10.1016/s1572-5995(05)80061-4 |

| 26. | Ma, S.-G.; Li, M.; Lin, M.-B.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.-B.; Qu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.-J.; Wang, R.-B.; Xu, S.; Hou, Q.; Yu, S.-S. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6160–6163. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03050 |

| 44. | Suzuki, T.; Nagahama, R.; Fariz, M. A.; Yukutake, Y.; Ikeuchi, K.; Tanino, K. Organics 2021, 2, 306–312. doi:10.3390/org2030016 |

| 41. | Wu, T. C.; Houk, K. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 5308–5309. doi:10.1021/ja00304a065 |

| 42. | Hayashi, Y.; Gotoh, H.; Honma, M.; Sankar, K.; Kumar, I.; Ishikawa, H.; Konno, K.; Yui, H.; Tsuzuki, S.; Uchimaru, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20175–20185. doi:10.1021/ja108516b |

| 43. | Carosso, S.; Miller, M. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 7445–7468. doi:10.1039/c4ob01033g |

| 30. | Gong, X.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306367. doi:10.1002/anie.202306367 |

| 32. | Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Lu, Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 23417–23421. doi:10.1021/jacs.5c07921 |

| 31. | Xu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 17592–17597. doi:10.1021/jacs.5c05409 |

| 39. | Occhialini, G.; Palani, V.; Wendlandt, A. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 145–152. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c12043 |

| 40. | Palani, V.; Wendlandt, A. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 20053–20061. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c06935 |

© 2025 Huang and Yang; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.