Abstract

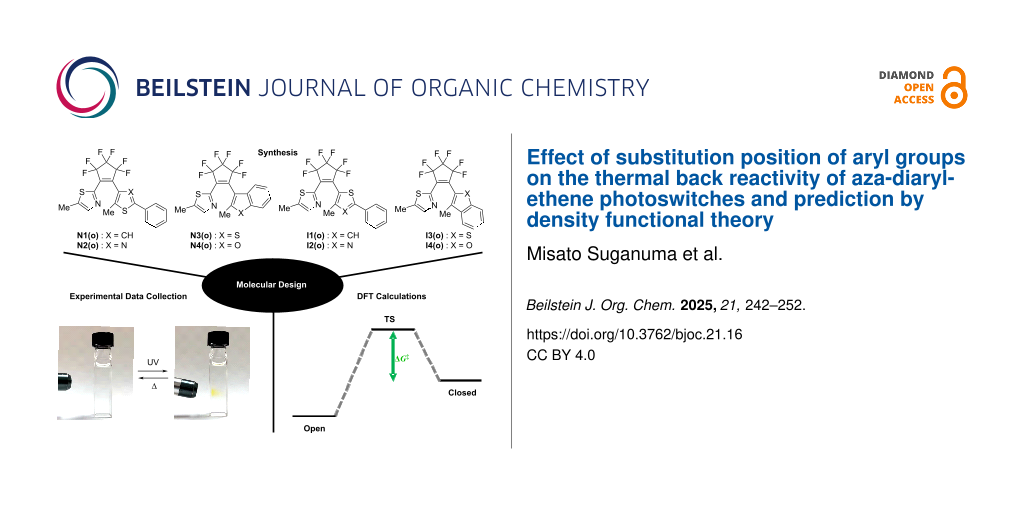

Aza-diarylethene has been developed as a new family of photochromic compounds. This study explores the photochromic properties and thermal back reactivities of various aza-diarylethene regioisomers (N1–N4 and I1–I4) in n-hexane. These molecules exhibit fast thermally reversible photochromic reactions driven by 6π aza-electrocyclization. Kinetic analysis of the thermal back reaction revealed activation parameters, highlighting how the substitution position of the aryl group affects the thermal stability. Additionally, density functional theory calculations identified M06 and MPW1PW91 as the most accurate functionals for predicting the thermal back reactivity, closely matching the experimental data. These findings offer valuable insights for the design of advanced photochromic materials with tailored thermal and photophysical characteristics.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Molecular photoswitches have been studied for a long time because their physicochemical properties such as refractive index [1,2], dipole moment [3,4], conductivity [5,6], magnetism [7,8], and fluorescence [9-11] can be spatiotemporally modulated by light without physical contact. Therefore, various application examples of molecular photoswitches have been reported so far including volumetric 3D printing [12,13], photoresponsive semiconductors [14-17], photopharmacology [18,19], energy storage materials [20-23], data storage materials [24], super-resolution microscopy [25-27], photomechanical materials [28-32], and so on. As seen in these representative application examples, the thermal stability of the colorless and colored isomers is one of the essential properties of molecular photoswitches. For example, the photochemically reversible-type (P-type) photoswitches [33,34], in which molecules isomerize upon photoirradiation and can maintain their state for a long time in the dark, are used for optical memories [35], displays [36,37], and photoresponsive actuators [38,39]. In contrast, the thermally reversible-type (T-type) photoswitches [40-42], in which the photogenerated isomers are thermally unstable at room temperature and return to the initial isomers not only by photoreaction but also by the thermal back reaction, are utilized for eyeglass lenses [43], security inks [44], and real-time holograms [45]. Especially, it is important to control and predict the thermal reactivity of T-type molecules, and many researchers have made their efforts to control the thermal reactivity in various molecular systems by performing chemical modifications on the molecular structures [46-48]. For instance, Aprahamian and co-workers reported that replacing the rotor pyridyl group of a hydrazone switch with a phenyl group afforded long-lived negative photochromic compounds [49]. In addition, Hecht and co-workers reported that the thermal stability of indigos can be tuned by N-functionalization [50,51]. They revealed that the introduction of electron-withdrawing substituents on the N-aryl moieties enhanced the thermal stability of the Z-isomers while maintaining the advantageous photoswitching properties upon irradiation with red light [52]. The effect of substituents on the thermal cis–trans isomerization of azobenzenes has also been widely studied, and push–pull derivatives bearing electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups at the para-position of the benzene rings are known to exhibit very fast thermal isomerizations [53]. Velasco and co-workers also reported that a pyrimidine-based azophenol exhibits thermal back reaction on the nanosecond time scale [54]. Langton and co-workers demonstrated that the thermal isomerization rate of azobenzenes can be tuned over a time scale spanning 107 seconds by introducing appropriate chalcogens and halogens at the ortho-position of the benzene rings [55]. Thus, investigation of the strategies to modulate the thermal reactivity in each molecular system is very important.

Recently, we have developed aza-diarylethenes N1 and N2 shown in Scheme 1, in which one of the reactive carbons of the diarylethene is replaced by nitrogen, as a new class of T-type photochromic compounds [56,57]. Aza-diarylethenes undergo fast thermal back reaction from the closed-ring isomer to the open-ring isomer with the half-life time of millisecond order. For the further development of aza-diarylethenes, it is essential to establish molecular design guidelines for controlling the thermal back reactivity. As one of the effective methods for predicting the thermal back reactivity, density functional theory (DFT) calculations can be considered [51,58-62]. For example, in previous studies on the thermal back reactivity of diarylbenzene that is an analogue of diarylethene, we found that the M06-2X level of theory in combination with the 6-31G(d) basis set well reproduces the experimental value of the activation energy for the thermal back reaction of various diarylbenzenes, resulting in the accurate prediction of the half-lifte time [58,63]. Thus, the combination of experiments and theoretical calculations can be a powerful tool for molecular design.

Scheme 1: Photochromic reaction of aza-diarylethene derivatives N1–N4 and I1–I4 investigated in this work.

Scheme 1: Photochromic reaction of aza-diarylethene derivatives N1–N4 and I1–I4 investigated in this work.

In this work, we newly synthesize various aza-diarylethene derivatives N3, N4, and I1–I4 with different substitution positions of the aryl group, and investigate their photochromic behaviors and thermal back reactivities as the data set for the prediction of thermal back reactivity. Moreover, we attempt to find the optimal functional for achieving a high correlation with experimental values by DFT calculation.

Results and Discussion

Photochromic properties in n-hexane

Compounds N1–N3 were synthesized according to the procedures described in the previous work [56,57], whereas compounds N4 and I1–I4 were synthesized according to Scheme 2 in the Experimental section. The chemical structures of all compounds were confirmed by 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra are shown in Supporting Information File 1.

The photochromic properties of N3, N4, and I1–I4 were investigated in n-hexane. Figure 1a,b and Figure S1 in Supporting Information File 1 show the absorption spectral changes of N3, N4, and I1–I4 in n-hexane upon UV light irradiation. Compounds N3(o), N4(o), and I1(o)–I4(o) have absorption maxima (λmax) at 299, 307, 291, 301, 307, and 369 nm, respectively. The molar absorption coefficients at λmax of N3(o), N4(o), and I1(o)–I4(o) were determined to be 12200, 12700, 47800, 22700, 12900, and 12700 M−1 cm−1, respectively. Upon irradiation with 365 nm, a new absorption band appeared in the visible region for all molecules, in which a visible absorption maximum was observed at 487, 467, 447, 454, and 440 nm for N3(c), N4(c), and I1(c)–I3(c). Note that the λmax of I4(c) could not be determined due to the overlapping absorption bands of the open-ring and closed-ring isomers. The absorption band in the visible region disappeared and returned to the initial one by stopping UV light irradiation. These results indicate that all molecules exhibit T-type photochromic reactions based on 6π aza-electrocyclic reaction. The absorption bands of compounds I1(c)–I4(c) are blue-shifted compared to N1(c)–N4(c), which is due to the localization of the π conjugation in the central part of the molecular skeleton as reported in inverse-type diarylethenes [64]. Figure 1c and the video (Supporting Information File 2) show the photochromic behavior of N4 at room temperature in n-hexane. It was confirmed that the colorless solution of N4(o) turned yellow upon irradiation with UV light and returned to the initial color upon removal of the irradiation. The photophysical properties of N3, N4, and I1–I4 are summarized in Table 1 together with the data of N1 and N2.

![[1860-5397-21-16-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-16-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Absorption spectral changes of (a) N3 and (b) I3 in n-hexane at 253 K for N3 and 203 K for I3: open-ring isomer (black line) and under irradiation at 365 nm (yellow line). (c) Photochromic reaction of N4 in n-hexane at room temperature ([N4] = 7.0 × 10−4 M).

Figure 1: Absorption spectral changes of (a) N3 and (b) I3 in n-hexane at 253 K for N3 and 203 K for I3: open...

Table 1: Photophysical properties and activation parameters for the thermal back reaction of compounds N1–N4 and I1–I4 in n-hexane.

| Open-ring isomer | Closed-ring isomer |

ΔH‡

[kJ mol−1] |

ΔS‡

[J mol−1 K−1] |

ΔG‡(exp)

[kJ mol−1]a |

k [s−1]a | t1/2 [ms]a | ||||

| λmax [nm] | ε [M−1 cm−1] | λmax [nm] | ||||||||

| N1b | 297 | 25200 | 522 | 61 | −3.0 | 62 | 100 | 6.8 | ||

| N2b | 300 | 25200 | 524 | 62 | −5.2 | 63 | 56 | 12 | ||

| N3 | 299 | 12200 | 487 | 57 | −25 | 64 | 42 | 17 | ||

| N4 | 307 | 12700 | 467 | 64 | −4.9 | 66 | 20 | 35 | ||

| I1 | 291 | 47800 | 447 | 49 | −19 | 55 | 1600 | 0.44 | ||

| I2 | 301 | 22700 | 454 | 58 | −20 | 64 | 38 | 18 | ||

| I3 | 307 | 12900 | 440 | 58 | 11 | 55 | 1700 | 0.41 | ||

| I4 | 369 | 12700 | – | 66 | 9.5 | 63 | 59 | 12 | ||

aAt 298 K. bReference [56].

Thermal back reactivity in n-hexane

To quantitatively evaluate the thermal back reaction of compounds N3, N4, and I1–I4, we measured the absorbance decay of the close-ring isomer at various temperatures as shown in Figure 2a,d, and Figure S2 in Supporting Information File 1. The absorbance decay curves obeyed the first-order kinetics and the rate constants (k) of the thermal back reactions at various temperatures were determined (Figure 2b,e and Supporting Information File 1, Figure S3 and Tables S1–S6). Figure 2c and 2f, and Figure S4 in Supporting Information File 1 show the temperature dependence of k (Eyring plots) for compounds N3, N4, and I1–I4. The activation enthalpy (ΔH‡) and activation entropy (ΔS‡) in the thermal reaction were determined from the intercept and slope. Using these values, the experimental activation free energy (ΔG‡(exp)), the k value, and the half-life (t1/2) at 298 K were calculated and the results are summarized in Table 1 with the data of N1 and N2. The ΔG‡(exp) values of N3, N4, and I1–I4 were 64, 66, 55, 64, 55, and 63 kJ mol−1, respectively. The t1/2 values of N3, N4, and I1–I4 were 17, 35, 0.44, 18, 0.41, and 12 ms, respectively, indicating that the compounds N3, N4, and I1–I4 have fast thermal back reactivities on the order of sub-ms to ms as well as N1 and N2. These thermal back reaction rates are comparable to those of diarylbenzene derivatives, hexaarylbiimidazole derivatives, and naphthopyran derivatives, which are known as fast T-type molecules [41,65,66].

![[1860-5397-21-16-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-16-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Absorbance decay curves and first-order kinetics profiles for (a,b) N3 and (d,e) I3 in n-hexane at various temperatures. Absorbance was monitored at λmax. (c) and (f) show Eyring plots for the thermal back reaction of N3 and I3, respectively.

Figure 2: Absorbance decay curves and first-order kinetics profiles for (a,b) N3 and (d,e) I3 in n-hexane at ...

Investigating the ΔH‡ and ΔS‡ values from the viewpoint of substitution position, when the aryl group is phenylthiophene (N1 and I1) or phenylthiazole (N2 and I2), both the ΔH‡ and the ΔS‡ values decreased by the change of the substitution position of the aryl group from N to I. In contrast, when the aryl group is benzothiophene (N3 and I3) or benzofuran (N4 and I4), the ΔH‡ values were almost the same, but the ΔS‡ values became larger and took positive values by the change of the substitution position of the aryl group from N to I. Furthermore, comparing the ΔG‡(exp) and the t1/2 values, when the aryl group is phenylthiophene (N1 and I1) or benzothiophene (N3 and I3), the ΔG‡(exp) value decreased and the t1/2 became shorter by the change of the substitution position of the aryl group from N to I. On the other hand, when the aryl group is phenylthiazole (N2 and I2) or benzofuran (N4 and I4), the ΔG‡(exp) and the t1/2 values were almost similar regardless of the substitution position of the aryl group. At the present time, there is no clear answer that can explain how the substitution position affects these values, but our results indicate that the substitution position of the aryl group can affect the thermal back reactivity of aza-diarylethenes, which is a valuable information for the molecular design to modulate the thermal back reactivity of aza-diarylethenes.

Quantum chemical calculations

Based on the thermal back reactivity of aza-diarylethenes described above, we explored the most suitable functional that well reproduces the ΔG‡(exp) values in DFT calculations. According to the previous studies on the prediction of the thermal back reactivity of diarylethene and diarylbenzene derivatives using DFT calculations, we performed geometry optimizations and harmonic frequency calculations of the closed-ring isomer and transition state for N1–N4 and I1–I4 using various functionals in combination with a 6-31G(d) basis set. The theoretical activation free energy (ΔG‡(calc)) at 298 K was determined as the difference in the sum of electronic energy and thermal free energy correction between the closed-ring isomer and the transition state (see Tables S7–S14 in Supporting Information File 1). Table 2 shows the differences in ΔG‡ between the theoretical value obtained by DFT calculations and the experimental value, i.e., ΔG‡(calc) − ΔG‡(exp). The B3LYP and M05 functionals underestimated the ΔG‡ value, while the BMK, CAMB3LYP, M05-2X, M06-2X, and ωB97X-D functionals overestimated the ΔG‡ value. Moreover, it was found that when M06 and MPW1PW91 were used as functionals, the theoretical values well reproduced the experimental values for all compounds. The errors between ΔG‡(calc) andΔG‡(exp) values were within 6.6 kJ mol−1 and the mean absolute error is within 3.76 kJ mol−1. This value is comparable to those described in previous studies [58-60,62,63]. The difference between ΔG‡(calc) andΔG‡(exp) values is visualized in Figure 3. Thus, we have found functionals that allow more accurate prediction of the thermal back reactivity of aza-diarylethenes.

Table 2: The differences in ΔG‡ between the theoretical value by DFT calculations and the experimental value (in kJ mol−1).

| N1 | N2 | N3 | N4 | I1 | I2 | I3 | I4 | MAEa | RMSEb | |

| B3LYP | −9.29 | −7.15 | −8.76 | −12.7 | −15.2 | −15.4 | −13.6 | −14.4 | 12.0 | 77.0 |

| BMK | 12.7 | 14.6 | 14.4 | 5.51 | 7.34 | 7.99 | 6.95 | 10.1 | 9.94 | 55.0 |

| CAMB3LYP | 5.43 | 7.96 | 7.89 | 3.47 | 3.48 | 3.86 | 5.66 | 6.99 | 5.59 | 17.2 |

| M05 | −9.22 | −7.07 | −9.31 | −13.3 | −12.9 | −13.5 | −9.27 | −9.95 | 10.6 | 58.3 |

| M06 | 0.00644 | 3.15 | −1.78 | −5.59 | −6.60 | −5.91 | −3.04 | −4.02 | 3.76 | 9.27 |

| M05-2x | 6.39 | 9.66 | 7.09 | 4.62 | 5.15 | 3.09 | 7.14 | 7.79 | 6.37 | 22.1 |

| M06-2x | 5.85 | 8.94 | 7.32 | 2.70 | 4.30 | 3.42 | 7.39 | 8.11 | 6.00 | 20.3 |

| MPW1PW91 | −0.710 | 1.98 | −0.744 | −3.53 | −6.16 | −6.00 | −2.79 | −3.92 | 3.23 | 7.16 |

| ωB97X-D | 7.41 | 10.5 | 8.61 | 3.84 | 7.11 | 7.10 | 9.35 | 10.3 | 8.03 | 34.3 |

aMAE : Mean absolute error. bRMSE : Root mean squared error.

![[1860-5397-21-16-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-16-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Visualization of the difference between ΔG‡(calcd) and ΔG‡(exp) for N1–N4 and I1–I4 by calculation using various functionals.

Figure 3: Visualization of the difference between ΔG‡(calcd) and ΔG‡(exp) for N1–N4 and I1–I4 by calculation ...

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the photochromic properties and thermal back reactivities of compounds N1–N4 and I1–I4 in n-hexane. All molecules exhibited T-type photochromic reactions through 6π aza-electrocyclic reactions, with significant changes in the absorption spectra upon UV irradiation. Notably, compound N4 turns bright yellow under UV light, adding a new color to the photochromic reaction of azadiarylethenes. The analysis of the thermal back reaction revealed activation parameters and highlighted the influence of the substitution position of the aryl group on thermal reactivity, providing a foundation for future molecular modifications. Furthermore, DFT calculations identified M06 and MPW1PW91 as the most suitable functionals for accurately predicting the thermal back reactivity of aza-diarylethenes, achieving a high correlation with experimental values. These results contribute to the design of advanced photochromic materials with tailored thermal and photophysical properties.

Experimental

General

Commercially available reagents were used as received for the syntheses. Solvents used for spectroscopy were of spectroscopic grade or purified by distillation before use. 1H NMR (300 MHz) and 13C NMR (75 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV-300N spectrometer with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were measured on a JEOL AccTOF LC mass spectrometer. UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded using a JASCO V-560 absorption spectrometer or an Ocean Optics FLAME-S multichannel analyzer. Photoirradiation (365 nm) to solution samples was carried out using a 200 W mercury–xenon lamp (MORITEX MSU-6) with a band-pass filter or a 365 nm UV-LED lamp (Keyence UV-400) as a light source. The solution samples were not degassed. The temperature control for UV–vis absorption spectral measurements was carried out using a UNISOKU CoolSpek UV/CD or an Ocean Optics CUV-QPOD.

Material

Synthesis of compounds N4 and I1–I4

The synthesis of the compounds is shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2: Synthetic route to aza-diarylethenes N4 and I1–I4.

Scheme 2: Synthetic route to aza-diarylethenes N4 and I1–I4.

4-Methyl-5-(perfluorocyclopent-1-en-1-yl)-2-phenylthiazole (I2(a)). Compound I2(a) was synthesized in a manner similar to a procedure from [67]. 5-Bromo-4-methyl-2-phenylthiazole (2.0 g, 7.9 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (200 mL) under argon atmosphere. A 1.6 M n-BuLi hexane solution (5.4 mL, 8.7 mmol) was slowly added dropwise to the solution at −78 °C, and the mixture was refluxed for 20 min. Perfluorocyclopentene (1.2 mL, 8.7 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h. An adequate amount of distilled water was added to the mixture to quench the reaction. The reaction mixture was neutralized by an aqueous HCl solution, extracted with ether, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane and ethyl acetate 95:5 to give 1.4 g of I2(a) in 50% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ = 2.55 (d, JHF = 3.2 Hz, 3H, CH3), 7.45–7.50 (m, 3H, aromatic H), 7.93–7.97 (m, 2H, aromatic H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 17.25, 17.31, 111.87, 126.93, 129.29, 131.31, 132.62, 157.67, 171.07, 171.09; HRMS–DART+ (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C15H9F7NS+, 368.0344; found, 368.0350.

3-Methyl-2-(perfluorocyclopent-1-en-1-yl)benzofuran (I4(a)). Compound I4(a) was synthesized in a manner similar to a procedure from [56]. 3-Methylbenzofuran (2.0 g, 15 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (200 mL) under argon atmosphere. A 1.6 M n-BuLi hexane solution (10 mL, 17 mmol) was slowly added dropwise to the solution at −78 °C, and the mixture was refluxed for 40 min. Perfluorocyclopentene (2.2 mL, 17 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 5 h. An adequate amount of distilled water was added to the mixture to quench the reaction. The reaction mixture was neutralized by HCl aqueous solution, extracted with ether, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane to give 2.8 g of I4(a) in 56% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ = 2.42 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.29–7.34 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.40–7.46 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.49–7.53 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.59–7.62 (m, 1H, aromatic H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.78, 8.81, 8.86, 8.90, 111.83, 120.64, 122.65, 122.70, 123.54, 127.61, 129.11, 137.03, 137.12, 155.39, 155.41; HRMS–DART+ (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C14H8F7OS+, 325.0463; found, 325.0467.

1-(5-Methylthiazol-2-yl)-2-(2-methylbenzo[b]furan-3-yl)perfluorocyclopentene (N4). Compound N4 was synthesized in a manner similar to a procedure from [56]. 5-Methylthiazole (0.20 g, 2.1 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (30 mL) under argon atmosphere. A 1.6 M n-BuLi hexane solution (1.4 mL, 2.3 mmol) was slowly added dropwise to the solution at −78 °C, and the mixture was refluxed for 40 min. 2-Methyl-3-(perfluorocyclopent-1-en-1-yl)benzofuran [68] (0.73 g, 2.3 mmol) dissolved in THF (5 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h. An adequate amount of distilled water was added to the mixture to quench the reaction. The reaction mixture was neutralized by HCl aqueous solution, extracted with ether, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane and ethyl acetate 8:2 and recycling HPLC using chloroform as the eluent to give 0.49 g of N4 in 61% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ = 2.38 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.39 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.21–7.36 (m, 3H, aromatic H), 7.51–7.54 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.21–7.36 (m, 3H, aromatic H), 7.66–7.67 (m, 1H, aromatic H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 11.9, 13.3, 104.0, 111.4, 119.7, 123.8, 125.0, 126.6, 139.9, 142.8, 152.3, 155.0, 155.9; HRMS–DART+ (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C18H12F6NOS+ 404.0543; found, 404.0550.

1-(5-Methylthiazol-2-yl)-2-(3-methyl-5-phenylthiophen-2-yl)perfluorocyclopentene (I1). Compound I1 was synthesized in a manner similar to a procedure from [56]. 5-Methylthiazole (0.27 g, 2.7 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (20 mL) under argon atmosphere. A 1.6 M n-BuLi hexane solution (1.9 mL, 3.1 mmol) was slowly added dropwise to the solution at −78 °C, and the mixture was refluxed for 30 min. 3-Methyl-2-(perfluorocyclopent-1-en-1-yl)-5-phenylthiophene [69] (1.0 g, 2.7 mmol) dissolved in THF (8 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h. An adequate amount of distilled water was added to the mixture to quench the reaction. The reaction mixture was neutralized by an aqueous HCl solution, extracted with ether, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane and ethyl acetate 8:2 and recycling HPLC using chloroform as the eluent to give 0.68 g of I1 in 56% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ = 2.09 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.46 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.27 (s, 1H, aromatic H), 7.35–7.45 (m, 3H, aromatic H), 7.62–7.66 (m, 2H, aromatic H), 7.70–7.71 (m, 1H, aromatic H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.1, 15.0, 119.3, 126.0, 126.8, 128.7, 129.2 133.2, 140.3, 141.8, 142.9, 148.6, 152.6. HRMS–DART+ (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H14F6NS2+, 446.0472; found, 446.0480.

1-(5-Methylthiazol-2-yl)-2-(4-methyl-2-phenyl-5-thiazolyl)perfluorocyclopentene (I2). Compound I2 was synthesized in a manner similar to a procedure from [56]. 5-Methylthiazole (0.24 g, 2.4 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (30 mL) under argon atmosphere. A 1.6 M n-BuLi hexane solution (1.5 mL, 2.4 mmol) was slowly added dropwise to the solution at −78 °C, and the mixture was refluxed for 30 min. 4-Methyl-5-(perfluorocyclopent-1-en-1-yl)-2-phenylthiazole (0.80 g, 2.2 mmol) dissolved in THF (5 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 4 h. An adequate amount of distilled water was added to the mixture to quench the reaction. The reaction mixture was neutralized by an aqueous HCl solution, extracted with ether, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane and ethyl acetate 8:2 and recycling HPLC using chloroform as the eluent to give 0.39 g of I2 in 41% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ = 2.31 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.47–7.51 (m, 3H, aromatic H), 7.72 (q, 1H, aromatic H), 7.98–8.01 (m, 2H, aromatic H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.1, 16.4, 114.8, 126.9, 129.3, 131.2, 132.8 140.6, 143.2, 155.8, 171.2; HRMS–DART+ (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C19H13F6N2S2+, 447.0424; found, 447.0430.

1-(5-Methylthiazol-2-yl)-2-(3-methylbenzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)perfluorocyclopentene (I3). Compound I3 was synthesized in a manner similar to a procedure from [56]. 5-Methylthiazole (0.36 g, 3.6 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (30 mL) under argon atmosphere. A 1.6 M n-BuLi hexane solution (2.3 mL, 3.6 mmol) was slowly added dropwise to the solution at −78 °C, and the mixture was refluxed for 1 h. 3-Methyl-2-(perfluorocyclopent-1-en-1-yl)benzo[b]thiophene [69] (1.1 g, 3.6 mmol) dissolved in THF (5 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h. An adequate amount of distilled water was added to the mixture to quench the reaction. The reaction mixture was neutralized by an aqueous HCl solution, extracted with ether, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane and ethyl acetate 9:1 and recycling HPLC using chloroform as the eluent to give 0.83 g of I3 in 60% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ = 2.29 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.39 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.48–7.51 (m, 2H, aromatic H), 7.69–7.70 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.80–7.84 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.92–7.95 (m, 1H, aromatic H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 12.0, 12.8, 120.8, 122.9, 123.2, 124.8, 126.2, 135.9, 139.7 140.7, 141.1, 142.9, 152.3; HRMS–DART+ (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C18H12F6NS2+, 420.0315; found, 420.0314.

1-(5-Methylthiazol-2-yl)-2-(2-methylbenzofuran-2-yl)perfluorocyclopentene (I4). Compound I4 was synthesized in a manner similar to a procedure from [56]. 5-Methylthiazole (0.38 g, 3.8 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (30 mL) under argon atmosphere. A 1.6 M n-BuLi hexane solution (2.6 mL, 4.2 mmol) was slowly added dropwise to the solution at −78 °C, and the mixture was refluxed for 30 min. 3-Methyl-2-(perfluorocyclopent-1-en-1-yl)benzofuran (1.4 g, 4.2 mmol) dissolved in THF (5 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 4 h. An adequate amount of distilled water was added to the mixture to quench the reaction. The reaction mixture was neutralized by an aqueous HCl solution, extracted with ether, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane and ethyl acetate 8:2 and recycling HPLC using chloroform as the eluent to give 0.49 g of I4 in 31% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, TMS) δ = 2.20 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.33–7.36 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.41–7.56 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.49–7.52 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.60–7.63 (m, 1H, aromatic H), 7.70 (q, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H, aromatic H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 9.3, 12.0, 111.9, 120.6, 122.5, 123.4, 127.1, 129.3, 139.0, 140.0, 143.0, 152.3, 155.6. HRMS–DART+ (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C18H12F6NOS+, 404.0544; found, 404.0550.

Theoretical calculations

DFT calculations were performed in a manner similar to procedures from [58]. Geometry optimizations and frequency calculations of closed-ring isomers (closed) and transition states (TS) were carried out using Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01 program package. The TS structure was optimized using Opt = TS keyword with Berny algorithm. To obey unrestricted Kohn–Sham solution, the broken-symmetry guess was generated and followed using the keyword Guess (mix, always). The frequency calculation for the TS was carried out to confirm that there is only one imaginary frequency corresponding to the stretching vibration between the nitrogen and the carbon atoms at the reactive site. The frequency calculation for closed-ring isomers was carried out to confirm that there is no imaginary frequencies. Various functionals (B3LYP, BMK, CAMB3LYP, M05, M06, M05-2X, M06-2X, MPW1PW91, and ωB97X-D) in combination with a 6-31G(d) basis set were used for the calculations.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental details and analyses of thermal back reactions. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 2.0 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: Movie for photochromic behavior of N4. | ||

| Format: MP4 | Size: 1.7 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 3: Cartesian coordinates in DFT calculations. | ||

| Format: XLSX | Size: 295.0 KB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Biteau, J.; Chaput, F.; Lahlil, K.; Boilot, J.-P.; Tsivgoulis, G. M.; Lehn, J.-M.; Darracq, B.; Marois, C.; Lévy, Y. Chem. Mater. 1998, 10, 1945–1950. doi:10.1021/cm980106h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Z.; Müller, K.; Heidrich, S.; Koenig, M.; Hashem, T.; Schlöder, T.; Bléger, D.; Wenzel, W.; Heinke, L. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 6626–6633. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b02614

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, H.; Hui, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.; Xu, W.; Shuai, Z.; Zhu, D.; Guo, X. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2015, 1, 1500159. doi:10.1002/aelm.201500159

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jakobsson, F. L. E.; Marsal, P.; Braun, S.; Fahlman, M.; Berggren, M.; Cornil, J.; Crispin, X. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 18396–18405. doi:10.1021/jp9043573

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Katsonis, N.; Kudernac, T.; Walko, M.; van der Molen, S. J.; van Wees, B. J.; Feringa, B. L. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2006, 18, 1397–1400. doi:10.1002/adma.200600210

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gilat, S. L.; Kawai, S. H.; Lehn, J.-M. Chem. – Eur. J. 1995, 1, 275–284. doi:10.1002/chem.19950010504

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matsuda, K.; Irie, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7195–7201. doi:10.1021/ja000605v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sato, O.; Iyoda, T.; Fujishima, A.; Hashimoto, K. Science 1996, 272, 704–705. doi:10.1126/science.272.5262.704

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fukaminato, T.; Sasaki, T.; Kawai, T.; Tamai, N.; Irie, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14843–14849. doi:10.1021/ja047169n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Berberich, M.; Krause, A.-M.; Orlandi, M.; Scandola, F.; Würthner, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6616–6619. doi:10.1002/anie.200802007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nishimura, R.; Fujisawa, E.; Ban, I.; Iwai, R.; Takasu, S.; Morimoto, M.; Irie, M. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 4715–4718. doi:10.1039/d2cc00554a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Regehly, M.; Garmshausen, Y.; Reuter, M.; König, N. F.; Israel, E.; Kelly, D. P.; Chou, C.-Y.; Koch, K.; Asfari, B.; Hecht, S. Nature 2020, 588, 620–624. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-3029-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stüwe, L.; Geiger, M.; Röllgen, F.; Heinze, T.; Reuter, M.; Wessling, M.; Hecht, S.; Linkhorst, J. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2024, 36, 2306716. doi:10.1002/adma.202306716

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Areephong, J.; Browne, W. R.; Katsonis, N.; Feringa, B. L. Chem. Commun. 2006, 3930–3932. doi:10.1039/b608502d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Turetta, N.; Danowski, W.; Cusin, L.; Livio, P. A.; Hallani, R.; McCulloch, I.; Samorì, P. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 7982–7988. doi:10.1039/d2tc05444b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hou, L.; Leydecker, T.; Zhang, X.; Rekab, W.; Herder, M.; Cendra, C.; Hecht, S.; McCulloch, I.; Salleo, A.; Orgiu, E.; Samorì, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11050–11059. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c02961

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Orgiu, E.; Crivillers, N.; Herder, M.; Grubert, L.; Pätzel, M.; Frisch, J.; Pavlica, E.; Duong, D. T.; Bratina, G.; Salleo, A.; Koch, N.; Hecht, S.; Samorì, P. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 675–679. doi:10.1038/nchem.1384

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schulte, A. M.; Kolarski, D.; Sundaram, V.; Srivastava, A.; Tama, F.; Feringa, B. L.; Szymanski, W. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5326. doi:10.3390/ijms23105326

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Velema, W. A.; Szymanski, W.; Feringa, B. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2178–2191. doi:10.1021/ja413063e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Han, G. G. D.; Li, H.; Grossman, J. C. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1446. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01608-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mansø, M.; Petersen, A. U.; Wang, Z.; Erhart, P.; Nielsen, M. B.; Moth-Poulsen, K. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1945. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04230-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qiu, Q.; Yang, S.; Gerkman, M. A.; Fu, H.; Aprahamian, I.; Han, G. G. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 12627–12631. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c05384

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qiu, Q.; Shi, Y.; Han, G. G. D. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 11444–11463. doi:10.1039/d1tc01472b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Günther, K.; Grabicki, N.; Battistella, B.; Grubert, L.; Dumele, O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 8707–8716. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c02195

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Grotjohann, T.; Testa, I.; Leutenegger, M.; Bock, H.; Urban, N. T.; Lavoie-Cardinal, F.; Willig, K. I.; Eggeling, C.; Jakobs, S.; Hell, S. W. Nature 2011, 478, 204–208. doi:10.1038/nature10497

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, D.; Aktalay, A.; Jensen, N.; Uno, K.; Bossi, M. L.; Belov, V. N.; Hell, S. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14235–14247. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c05036

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deniz, E.; Tomasulo, M.; Cusido, J.; Yildiz, I.; Petriella, M.; Bossi, M. L.; Sortino, S.; Raymo, F. M. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 6058–6068. doi:10.1021/jp211796p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kitagawa, D.; Tsujioka, H.; Tong, F.; Dong, X.; Bardeen, C. J.; Kobatake, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4208–4212. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b13605

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kobatake, S.; Takami, S.; Muto, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Irie, M. Nature 2007, 446, 778–781. doi:10.1038/nature05669

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tong, F.; Kitagawa, D.; Bushnak, I.; Al‐Kaysi, R. O.; Bardeen, C. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2414–2423. doi:10.1002/anie.202012417

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barrett, C. J.; Mamiya, J.-i.; Yager, K. G.; Ikeda, T. Soft Matter 2007, 3, 1249–1261. doi:10.1039/b705619b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tamaoki, M.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 3093–3099. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.1c00270

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Irie, M. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1685–1716. doi:10.1021/cr980069d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kobatake, S.; Irie, M. Chem. Lett. 2004, 33, 904–905. doi:10.1246/cl.2004.904

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Irie, M.; Fukaminato, T.; Sasaki, T.; Tamai, N.; Kawai, T. Nature 2002, 420, 759–760. doi:10.1038/420759a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 9872–9881. doi:10.1039/d1nj01637g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morimoto, M.; Kashihara, R.; Mutoh, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Abe, J.; Sotome, H.; Ito, S.; Miyasaka, H.; Irie, M. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 7241–7248. doi:10.1039/c6ce00725b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 4421–4424. doi:10.1039/c5cc00355e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morimoto, M.; Irie, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 14172–14178. doi:10.1021/ja105356w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Natansohn, A.; Rochon, P. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4139–4176. doi:10.1021/cr970155y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kitagawa, D.; Nakahama, T.; Nakai, Y.; Kobatake, S. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 2865–2870. doi:10.1039/c8tc05357j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Sacherer, M.; Gracheva, S.; Maid, H.; Placht, C.; Hampel, F.; Dube, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 9575–9582. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c11803

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boelke, J.; Hecht, S. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1900404. doi:10.1002/adom.201900404

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ritchie, C.; Vamvounis, G.; Soleimaninejad, H.; Smith, T. A.; Bieske, E. J.; Dryza, V. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 19984–19991. doi:10.1039/c7cp02818k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blanche, P.-A.; Bablumian, A.; Voorakaranam, R.; Christenson, C.; Lin, W.; Gu, T.; Flores, D.; Wang, P.; Hsieh, W.-Y.; Kathaperumal, M.; Rachwal, B.; Siddiqui, O.; Thomas, J.; Norwood, R. A.; Yamamoto, M.; Peyghambarian, N. Nature 2010, 468, 80–83. doi:10.1038/nature09521

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shirinian, V. Z.; Lvov, A. G.; Bulich, E. Y.; Zakharov, A. V.; Krayushkin, M. M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 5477–5481. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.08.028

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maegawa, R.; Kitagawa, D.; Hamatani, S.; Kobatake, S. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 18969–18975. doi:10.1039/d1nj04047b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61, 151968. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2020.151968

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qian, H.; Pramanik, S.; Aprahamian, I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9140–9143. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04993

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, C.-Y. (D.); Hecht, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202300981. doi:10.1002/chem.202300981

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jaiswal, A. K.; Saha, P.; Jiang, J.; Suzuki, K.; Jasny, A.; Schmidt, B. M.; Maeda, S.; Hecht, S.; Huang, C.-Y. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 21367–21376. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c03543

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Huang, C.-Y.; Bonasera, A.; Hristov, L.; Garmshausen, Y.; Schmidt, B. M.; Jacquemin, D.; Hecht, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15205–15211. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b08726

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Whitten, D. G.; Wildes, P. D.; Pacifici, J. G.; Irick, G., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2004–2008. doi:10.1021/ja00737a027

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Garcia‐Amorós, J.; Díaz‐Lobo, M.; Nonell, S.; Velasco, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 12820–12823. doi:10.1002/anie.201207602

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kerckhoffs, A.; Christensen, K. E.; Langton, M. J. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 11551–11559. doi:10.1039/d2sc04601f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] -

Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202414121. doi:10.1002/anie.202414121

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kitagawa, D.; Takahashi, N.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 644–653. doi:10.1039/d0pp00024h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Li, X.; Zou, Q.; Ågren, H. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 9140–9147. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.5b04268

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Patel, P. D.; Masunov, A. E. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 10292–10297. doi:10.1021/jp200980v

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Dokić, J.; Gothe, M.; Wirth, J.; Peters, M. V.; Schwarz, J.; Hecht, S.; Saalfrank, P. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 6763–6773. doi:10.1021/jp9021344

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schweighauser, L.; Strauss, M. A.; Bellotto, S.; Wegner, H. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13436–13439. doi:10.1002/anie.201506126

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 96, 496–502. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20230074

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kudernac, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Uyama, A.; Uchida, K.; Nakamura, S.; Feringa, B. L. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 8222–8229. doi:10.1021/jp404924q

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kishimoto, Y.; Abe, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4227–4229. doi:10.1021/ja810032t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Inagaki, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Mutoh, K.; Abe, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13429–13441. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b06293

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kitagawa, D.; Seto, Y.; Suganuma, M.; Nakahama, T.; Sotome, H.; Ito, S.; Miyasaka, H.; Kobatake, S. ChemPhotoChem 2024, 8, e202400081. doi:10.1002/cptc.202400081

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, X.; Pu, S.; Li, H.; Liu, G. Dyes Pigm. 2014, 105, 47–56. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2014.01.019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, F.; Zhang, F.; Guo, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, R.; Zhao, F. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7615–7621. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(03)01141-4

Return to citation in text: [1] [2]

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

| 57. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202414121. doi:10.1002/anie.202414121 |

| 51. | Jaiswal, A. K.; Saha, P.; Jiang, J.; Suzuki, K.; Jasny, A.; Schmidt, B. M.; Maeda, S.; Hecht, S.; Huang, C.-Y. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 21367–21376. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c03543 |

| 58. | Kitagawa, D.; Takahashi, N.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 644–653. doi:10.1039/d0pp00024h |

| 59. | Li, X.; Zou, Q.; Ågren, H. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 9140–9147. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.5b04268 |

| 60. | Patel, P. D.; Masunov, A. E. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 10292–10297. doi:10.1021/jp200980v |

| 61. | Dokić, J.; Gothe, M.; Wirth, J.; Peters, M. V.; Schwarz, J.; Hecht, S.; Saalfrank, P. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 6763–6773. doi:10.1021/jp9021344 |

| 62. | Schweighauser, L.; Strauss, M. A.; Bellotto, S.; Wegner, H. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13436–13439. doi:10.1002/anie.201506126 |

| 58. | Kitagawa, D.; Takahashi, N.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 644–653. doi:10.1039/d0pp00024h |

| 63. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 96, 496–502. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20230074 |

| 1. | Biteau, J.; Chaput, F.; Lahlil, K.; Boilot, J.-P.; Tsivgoulis, G. M.; Lehn, J.-M.; Darracq, B.; Marois, C.; Lévy, Y. Chem. Mater. 1998, 10, 1945–1950. doi:10.1021/cm980106h |

| 2. | Zhang, Z.; Müller, K.; Heidrich, S.; Koenig, M.; Hashem, T.; Schlöder, T.; Bléger, D.; Wenzel, W.; Heinke, L. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 6626–6633. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b02614 |

| 9. | Fukaminato, T.; Sasaki, T.; Kawai, T.; Tamai, N.; Irie, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14843–14849. doi:10.1021/ja047169n |

| 10. | Berberich, M.; Krause, A.-M.; Orlandi, M.; Scandola, F.; Würthner, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6616–6619. doi:10.1002/anie.200802007 |

| 11. | Nishimura, R.; Fujisawa, E.; Ban, I.; Iwai, R.; Takasu, S.; Morimoto, M.; Irie, M. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 4715–4718. doi:10.1039/d2cc00554a |

| 36. | Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 9872–9881. doi:10.1039/d1nj01637g |

| 37. | Morimoto, M.; Kashihara, R.; Mutoh, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Abe, J.; Sotome, H.; Ito, S.; Miyasaka, H.; Irie, M. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 7241–7248. doi:10.1039/c6ce00725b |

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

| 7. | Matsuda, K.; Irie, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7195–7201. doi:10.1021/ja000605v |

| 8. | Sato, O.; Iyoda, T.; Fujishima, A.; Hashimoto, K. Science 1996, 272, 704–705. doi:10.1126/science.272.5262.704 |

| 38. | Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 4421–4424. doi:10.1039/c5cc00355e |

| 39. | Morimoto, M.; Irie, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 14172–14178. doi:10.1021/ja105356w |

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

| 5. | Katsonis, N.; Kudernac, T.; Walko, M.; van der Molen, S. J.; van Wees, B. J.; Feringa, B. L. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2006, 18, 1397–1400. doi:10.1002/adma.200600210 |

| 6. | Gilat, S. L.; Kawai, S. H.; Lehn, J.-M. Chem. – Eur. J. 1995, 1, 275–284. doi:10.1002/chem.19950010504 |

| 33. | Irie, M. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1685–1716. doi:10.1021/cr980069d |

| 34. | Kobatake, S.; Irie, M. Chem. Lett. 2004, 33, 904–905. doi:10.1246/cl.2004.904 |

| 58. | Kitagawa, D.; Takahashi, N.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 644–653. doi:10.1039/d0pp00024h |

| 59. | Li, X.; Zou, Q.; Ågren, H. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 9140–9147. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.5b04268 |

| 60. | Patel, P. D.; Masunov, A. E. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 10292–10297. doi:10.1021/jp200980v |

| 62. | Schweighauser, L.; Strauss, M. A.; Bellotto, S.; Wegner, H. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13436–13439. doi:10.1002/anie.201506126 |

| 63. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 96, 496–502. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20230074 |

| 3. | Zhang, H.; Hui, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.; Xu, W.; Shuai, Z.; Zhu, D.; Guo, X. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2015, 1, 1500159. doi:10.1002/aelm.201500159 |

| 4. | Jakobsson, F. L. E.; Marsal, P.; Braun, S.; Fahlman, M.; Berggren, M.; Cornil, J.; Crispin, X. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 18396–18405. doi:10.1021/jp9043573 |

| 35. | Irie, M.; Fukaminato, T.; Sasaki, T.; Tamai, N.; Kawai, T. Nature 2002, 420, 759–760. doi:10.1038/420759a |

| 67. | Kitagawa, D.; Seto, Y.; Suganuma, M.; Nakahama, T.; Sotome, H.; Ito, S.; Miyasaka, H.; Kobatake, S. ChemPhotoChem 2024, 8, e202400081. doi:10.1002/cptc.202400081 |

| 20. | Han, G. G. D.; Li, H.; Grossman, J. C. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1446. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01608-y |

| 21. | Mansø, M.; Petersen, A. U.; Wang, Z.; Erhart, P.; Nielsen, M. B.; Moth-Poulsen, K. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1945. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04230-8 |

| 22. | Qiu, Q.; Yang, S.; Gerkman, M. A.; Fu, H.; Aprahamian, I.; Han, G. G. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 12627–12631. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c05384 |

| 23. | Qiu, Q.; Shi, Y.; Han, G. G. D. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 11444–11463. doi:10.1039/d1tc01472b |

| 25. | Grotjohann, T.; Testa, I.; Leutenegger, M.; Bock, H.; Urban, N. T.; Lavoie-Cardinal, F.; Willig, K. I.; Eggeling, C.; Jakobs, S.; Hell, S. W. Nature 2011, 478, 204–208. doi:10.1038/nature10497 |

| 26. | Kim, D.; Aktalay, A.; Jensen, N.; Uno, K.; Bossi, M. L.; Belov, V. N.; Hell, S. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14235–14247. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c05036 |

| 27. | Deniz, E.; Tomasulo, M.; Cusido, J.; Yildiz, I.; Petriella, M.; Bossi, M. L.; Sortino, S.; Raymo, F. M. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 6058–6068. doi:10.1021/jp211796p |

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

| 18. | Schulte, A. M.; Kolarski, D.; Sundaram, V.; Srivastava, A.; Tama, F.; Feringa, B. L.; Szymanski, W. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5326. doi:10.3390/ijms23105326 |

| 19. | Velema, W. A.; Szymanski, W.; Feringa, B. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2178–2191. doi:10.1021/ja413063e |

| 28. | Kitagawa, D.; Tsujioka, H.; Tong, F.; Dong, X.; Bardeen, C. J.; Kobatake, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4208–4212. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b13605 |

| 29. | Kobatake, S.; Takami, S.; Muto, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Irie, M. Nature 2007, 446, 778–781. doi:10.1038/nature05669 |

| 30. | Tong, F.; Kitagawa, D.; Bushnak, I.; Al‐Kaysi, R. O.; Bardeen, C. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2414–2423. doi:10.1002/anie.202012417 |

| 31. | Barrett, C. J.; Mamiya, J.-i.; Yager, K. G.; Ikeda, T. Soft Matter 2007, 3, 1249–1261. doi:10.1039/b705619b |

| 32. | Tamaoki, M.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 3093–3099. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.1c00270 |

| 41. | Kitagawa, D.; Nakahama, T.; Nakai, Y.; Kobatake, S. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 2865–2870. doi:10.1039/c8tc05357j |

| 65. | Kishimoto, Y.; Abe, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4227–4229. doi:10.1021/ja810032t |

| 66. | Inagaki, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Mutoh, K.; Abe, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13429–13441. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b06293 |

| 14. | Areephong, J.; Browne, W. R.; Katsonis, N.; Feringa, B. L. Chem. Commun. 2006, 3930–3932. doi:10.1039/b608502d |

| 15. | Turetta, N.; Danowski, W.; Cusin, L.; Livio, P. A.; Hallani, R.; McCulloch, I.; Samorì, P. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 7982–7988. doi:10.1039/d2tc05444b |

| 16. | Hou, L.; Leydecker, T.; Zhang, X.; Rekab, W.; Herder, M.; Cendra, C.; Hecht, S.; McCulloch, I.; Salleo, A.; Orgiu, E.; Samorì, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11050–11059. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c02961 |

| 17. | Orgiu, E.; Crivillers, N.; Herder, M.; Grubert, L.; Pätzel, M.; Frisch, J.; Pavlica, E.; Duong, D. T.; Bratina, G.; Salleo, A.; Koch, N.; Hecht, S.; Samorì, P. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 675–679. doi:10.1038/nchem.1384 |

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

| 57. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202414121. doi:10.1002/anie.202414121 |

| 12. | Regehly, M.; Garmshausen, Y.; Reuter, M.; König, N. F.; Israel, E.; Kelly, D. P.; Chou, C.-Y.; Koch, K.; Asfari, B.; Hecht, S. Nature 2020, 588, 620–624. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-3029-7 |

| 13. | Stüwe, L.; Geiger, M.; Röllgen, F.; Heinze, T.; Reuter, M.; Wessling, M.; Hecht, S.; Linkhorst, J. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2024, 36, 2306716. doi:10.1002/adma.202306716 |

| 24. | Günther, K.; Grabicki, N.; Battistella, B.; Grubert, L.; Dumele, O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 8707–8716. doi:10.1021/jacs.2c02195 |

| 64. | Kudernac, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Uyama, A.; Uchida, K.; Nakamura, S.; Feringa, B. L. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 8222–8229. doi:10.1021/jp404924q |

| 44. | Ritchie, C.; Vamvounis, G.; Soleimaninejad, H.; Smith, T. A.; Bieske, E. J.; Dryza, V. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 19984–19991. doi:10.1039/c7cp02818k |

| 40. | Natansohn, A.; Rochon, P. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4139–4176. doi:10.1021/cr970155y |

| 41. | Kitagawa, D.; Nakahama, T.; Nakai, Y.; Kobatake, S. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 2865–2870. doi:10.1039/c8tc05357j |

| 42. | Sacherer, M.; Gracheva, S.; Maid, H.; Placht, C.; Hampel, F.; Dube, H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 9575–9582. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c11803 |

| 68. | Li, X.; Pu, S.; Li, H.; Liu, G. Dyes Pigm. 2014, 105, 47–56. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2014.01.019 |

| 43. | Boelke, J.; Hecht, S. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1900404. doi:10.1002/adom.201900404 |

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

| 69. | Sun, F.; Zhang, F.; Guo, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, R.; Zhao, F. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7615–7621. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(03)01141-4 |

| 54. | Garcia‐Amorós, J.; Díaz‐Lobo, M.; Nonell, S.; Velasco, D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 12820–12823. doi:10.1002/anie.201207602 |

| 55. | Kerckhoffs, A.; Christensen, K. E.; Langton, M. J. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 11551–11559. doi:10.1039/d2sc04601f |

| 52. | Huang, C.-Y.; Bonasera, A.; Hristov, L.; Garmshausen, Y.; Schmidt, B. M.; Jacquemin, D.; Hecht, S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15205–15211. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b08726 |

| 58. | Kitagawa, D.; Takahashi, N.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 644–653. doi:10.1039/d0pp00024h |

| 53. | Whitten, D. G.; Wildes, P. D.; Pacifici, J. G.; Irick, G., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2004–2008. doi:10.1021/ja00737a027 |

| 49. | Qian, H.; Pramanik, S.; Aprahamian, I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9140–9143. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04993 |

| 69. | Sun, F.; Zhang, F.; Guo, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, R.; Zhao, F. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7615–7621. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(03)01141-4 |

| 50. | Huang, C.-Y. (D.); Hecht, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202300981. doi:10.1002/chem.202300981 |

| 51. | Jaiswal, A. K.; Saha, P.; Jiang, J.; Suzuki, K.; Jasny, A.; Schmidt, B. M.; Maeda, S.; Hecht, S.; Huang, C.-Y. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 21367–21376. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c03543 |

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

| 45. | Blanche, P.-A.; Bablumian, A.; Voorakaranam, R.; Christenson, C.; Lin, W.; Gu, T.; Flores, D.; Wang, P.; Hsieh, W.-Y.; Kathaperumal, M.; Rachwal, B.; Siddiqui, O.; Thomas, J.; Norwood, R. A.; Yamamoto, M.; Peyghambarian, N. Nature 2010, 468, 80–83. doi:10.1038/nature09521 |

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

| 46. | Shirinian, V. Z.; Lvov, A. G.; Bulich, E. Y.; Zakharov, A. V.; Krayushkin, M. M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 5477–5481. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.08.028 |

| 47. | Maegawa, R.; Kitagawa, D.; Hamatani, S.; Kobatake, S. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 18969–18975. doi:10.1039/d1nj04047b |

| 48. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Nakahama, T.; Kobatake, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61, 151968. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2020.151968 |

| 56. | Hamatani, S.; Kitagawa, D.; Kobatake, S. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 8277–8280. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02207 |

© 2025 Suganuma et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.