Abstract

An atom- and step-economical electrochemical method for the synthesis of aliphatic nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds from the corresponding nitroso compounds was developed employing ammonium dinitramide, a prospective green oxidant for aerospace propulsion applications, as both electrolyte and source of a =NNO2 group. The developed method is green, practical, and scalable due to constant current electrolysis in an undivided cell at high current densities. Synthesized products demonstrated pronounced NO-donor activity and fungicidal activity against phytopathogenic fungi.

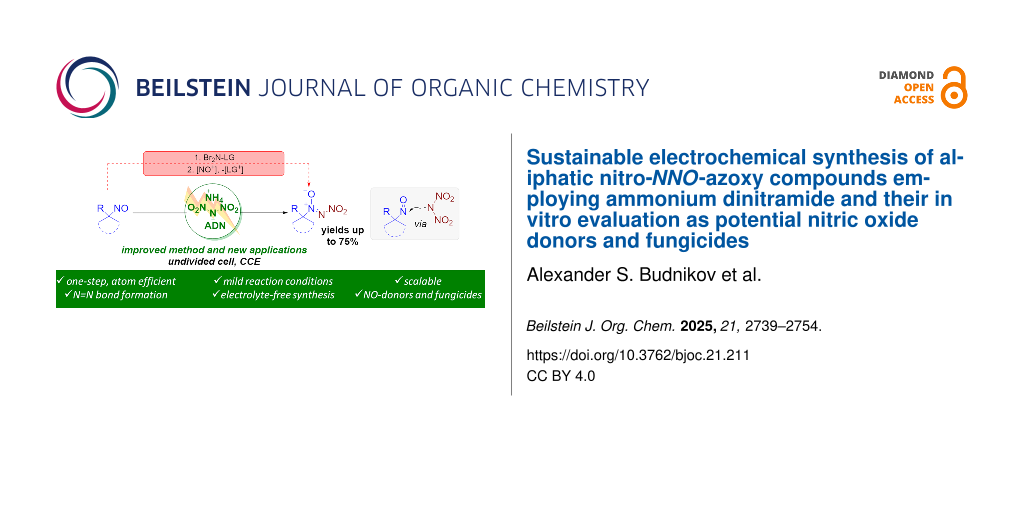

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Organic compounds containing N–N and N–O bonds are ubiquitous in diverse fields, including pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, natural products [1-4], as well as in applications in organic synthesis as precursors for free radicals in selective transformations [5-11] and polymerization initiators [12], energetic materials [13-15], NO donors [16,17], and organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) [18]. Despite the wide diversity of their applications, structures, and redox properties, effective synthetic strategies for the construction of N–N and N–O systems remain markedly underdeveloped. Unlike traditional methods for constructing C–C and C–Het bonds, the number of methods for selective N–N [1,5,19-29] and N–O [30-35] coupling is very limited. In most existing approaches, the N–N and N–O moieties are derived from hydrazine or hydroxylamine synthons, respectively. The development of novel synthetic methodologies based on non-traditional retrosynthetic disconnections offers a potential pathway to overcome existing constraints in functional group compatibility, efficiency, and reagent scope. In this regard, the direct formation of nitrogen-nitrogen or nitrogen-oxygen bonds presents a significant challenge due to the variety of possible side processes and the low thermodynamic driving force for N–N and N–O bond formation. However, it also represents a highly efficient and valuable strategy due to the synthetic availability of starting materials. Therefore, the development of new methods for direct selective N–N and N–O coupling remains an important goal in synthetic chemistry.

To date, electroorganic synthesis has become a powerful and reliable strategy for the functionalization of organic compounds under green and mild reaction conditions [36-39]. The control of selectivity through the variation of parameters such as current, voltage, electrolyte, electrodes, and the type of electrochemical cell distinguishes electroorganic synthesis from traditional organic chemistry methods. Particular attention is paid to the generation of radical intermediates via the oxidation or reduction of radical precursors [40-49]. In this regard, the anodic oxidation of nitrogen compounds leading to the formation of N-centered radicals has proven to be a convenient approach [15,42,47,48] to the formation of C–N [50,51] and N–Het [52,53] bonds. However, the electrochemical construction of N–N and N=N bonds remains very limited. The vast majority of developed approaches focus mainly on intramolecular radical cyclizations [42,54-63], while intermolecular [1,64-68] N–N coupling remains a poorly studied area.

In addition to the preparation of azo compounds [69,70], intermolecular N–N coupling reactions are of particular interest for the regioselective synthesis of azoxy compounds [5,71,72]. Unique and understudied representatives of the latter are nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds [R–N(O)=N–NO2], first synthesized at ZIOC RAS [73-75]. Nowadays, aromatic and heterocyclic compounds of this class have been studied in most detail and attract continuing attention as perspective high-energy materials [76-86] and physiologically active substances [87]. At the same time, aliphatic compounds containing the nitro-NNO-azoxy group are practically unknown, with the exception of a few representatives [88].

The most general two-step approach to the synthesis of nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds is shown in Scheme 1a. The first step includes the reaction of nitroso compounds R–N=O with N,N-dibromoamines Br2NX (X = Ac [73], t-Bu [74], CO2t-Bu [74], C(O)NH2 [74]) leading to azoxy compounds containing a leaving group X. The second step is substitutive nitration of the latter with nitronium salts (NO2BF4, (NO2)2SiF6) or N2O5). The main limitations of this approach are the use of hazardous and expensive nitrating reagents and its inapplicability for preparation of nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds containing substituents that are labile towards electrophiles. Thus, there is a need for new, more efficient methods for the synthesis of nitro-NNO-azoxy derivatives that do not have the disadvantages of the known approach and allow the use of a wide range of substrates, including various aliphatic ones.

Scheme 1: Current synthetic approaches to aliphatic nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds and the summary of the present work achievements.

Scheme 1: Current synthetic approaches to aliphatic nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds and the summary of the present ...

Recently, our group developed a one-step electrochemical approach to the synthesis of nitro-NNO-azoxy arenes employing ammonium dinitramide (ADN) [87]. The achieved use of ADN, known as prospective chlorine-free green oxidant for aerospace propulsion applications [89-91], as both a reagent and an electrolyte is very important, as it overcomes one of the major obstacles to the sustainability and scalability of organic electrosynthesis: the need for a supporting electrolyte in addition to reactants. The synthesized nitro-NNO-azoxy arenes were discovered as a novel class of fungicides, with in vitro activity against a broad range of phytopathogenic fungi that is comparable or superior to that of commercial fungicides. In the present study, we sought to expand the developed nitro-NNO-azoxylation strategy to aliphatic nitroso compounds. However, our numerous attempts involving various nitroso compounds or oximes (X = H) with ADN were unsuccessful, as the NO group or oxime group did not participate in the desired N=N coupling (Scheme 1, substrates S1–S4). These substrates underwent either deep oxidation or degradation. Ultimately, in the reaction of 1-nitrosocyclohexane-1-carbonitrile (S5) and 1-nitro-1-nitrosocyclohexane (S6) we observed products of N=N coupling with ammonium dinitramide. Presumably, the presence of a strong electron-withdrawing group prevents further oxidation of the NO group prior to the oxidation of ADN. Herein, we report a green and sustainable electrochemical coupling of aliphatic nitroso compounds with ammonium dinitramide, leading to efficient formation of the nitro-NNO-azoxy group. The developed strategy involves performing the electrosynthesis in an undivided cell under high current density with ADN employed as both a reagent and an electrolyte. The synthesized aliphatic nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds were identified as promising NO-donors and were found to exhibit pronounced fungicidal activity against a broad spectrum of phytopathogenic fungi.

Results and Discussion

The conditions of the electrochemical coupling of aliphatic nitroso compounds with ammonium dinitramide (ADN) leading to the construction of a nitro-NNO-azoxy fragment were optimized on the model reaction of 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a) and ADN as coupling partners (Table 1). The influence of material of electrodes, the amount of electricity, current density, supporting electrolyte, solvent nature, and atmosphere are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Optimization of the reaction conditions.a

|

|

||

| Entry | Variations from standard reaction conditions | Yieldb 2a, % |

| 1 | none | 77 (75) |

| 2 | SS/Ni/CF/C/GC as anode (+) | <5/<5/56/29/68 |

| 3 | Pt/SS/Ni/CF/C/GC as cathode (−) | 63/54/70/27/53/67 |

| 4 | 1/1.5/3 F per mole of 1a, I = 60 mA, (+) Pt/Ptw (−) | 48/68/76 |

| 5 | I = 15/30/120/240 mA, (+) Pt/Ptw (−) | 72/77/62/32 |

| 6 | ADN (0.5 mmol), n-Bu4NBF4 (0.5 mmol) | 28 |

| 7 | KDN (2 mmol), n-Bu4NBF4 (0.5 mmol) | 26 |

| 8 | 1/1.5/2.5 mmol ADN | 37/60/69 |

| 9 | acetone/DMF/MeOH/HFIP as solvent | <5/n.d./<5/<5 |

| 10 | Ar atmosphere | 65 |

| 11 | without electricity | n.d. |

aStandard reaction conditions: 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a, 60 mg, 0.5 mmol), ADN (62–310 mg, 0.5–2.5 mmol), electrolyte or additive (0–288 mg), solvent (10 mL), undivided cell, constant current electrolysis (CCE) with I = 15–240 mA, F = 1–3 F/mol 1a (reaction time 7–107 min), air atmosphere. C – graphite plate, GC – glassy carbon plate, CF – carbon felt, Pt – platinum plate, Ptw – platinum wire, SS – stainless steel plate, Ni – nickel plate. bThe yield was determined by 1H NMR using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an internal standard; the isolated yields are given in parentheses. n.d. – not detected. The bold text of entry 1 indicates conditions as optimal.

After extensive optimization, we found that a 77% yield (75% isolated yield) of 2a was achieved by performing the model reaction under CCE (constant current electrolysis) conditions in an undivided electrochemical cell, using a platinum plate as the anode and a platinum wire as the cathode, with 4 equiv of ADN as both the reagent and the supporting electrolyte (Table 1, entry 1). Entries 2 and 3 show that the best results were obtained with a platinum plate anode and a platinum wire cathode. The evaluation of the charge passed revealed that the optimal amount was 2 F per mole 1a (Table 1, entry 4). Increasing the current density resulted in a drop in the yield to 32%, while reducing the current density had a negligible effect on the yield of 2a (Table 1, entry 5). Employing 1 equivalent of ADN or potassium dinitramide (KDN) along with 1 equivalent of n-Bu4NBF4 as the supporting electrolyte proved ineffective: the yield of 2a did not exceed 28% (Table 1, entries 6 and 7). Screening of the amount of ADN revealed that 2 mmol per 0.5 mmol of 1a was optimal (Table 1, entry 8). MeCN proved to be the best solvent for the present electrochemical coupling, while performing the reaction in other polar protic and aprotic solvents resulted in only trace amounts of 2a (Table 1, entry 9). Entry 10 shows that no significant change in the yield of 2a was observed when conducting the electrosynthesis in an inert atmosphere. Finally, no reaction was observed in the absence of electrical current (Table 1, entry 11).

Under optimized reaction conditions (Table 1, entry 1), the scope of the electrochemical nitro-NNO-azoxylation protocol was tested (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Scope of the discovered electrochemical nitro-NNO-azoxylation of nitrosoalkanes containing electron-withdrawing groups.

Scheme 2: Scope of the discovered electrochemical nitro-NNO-azoxylation of nitrosoalkanes containing electron...

The reaction proceeds in moderate to good yields for cyclic aliphatic nitroso compounds 1b–d, affording nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds 2b–d. The structure of 2c was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray analysis. The benzyl moiety was also tolerated, and the corresponding product 2e was obtained in 57% yield. 2,2-Dimethyl-5-nitro-5-nitroso-1,3-dioxane (1f) was successfully employed under the reaction conditions, leading to the formation of product 2f in 68% yield without cleavage of the acetonide protecting group. Note that compound 2f is not accessible using the known approach (see Scheme 1a), because the dioxane ring is opened during the nitration step. Surprisingly, nitro-NNO-azoxylation products 2g and 2h were obtained from methyl and ethyl 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropanoates (1g and 1h), which contain an additional electron-withdrawing ester group in geminal position. Finally, 1-nitrosocyclohexane-1-carbonitrile (1i) was also tolerated under the reaction conditions, affording product 2i in 61% yield.

The robustness of the developed protocol was further demonstrated by performing the model reaction on a 6 mmol scale of 1f (Scheme 3, reaction 1). The corresponding product 2f was obtained without any erosion of the yield (1.02 g, 4.08 mmol, 68%). The acidic cleavage of the acetonide group in 2f with AcCl in MeOH afforded diol 3f in a 94% yield. Subsequent nitration of the obtained diol 3f with a HNO3/Ac2O mixture afforded dinitrate 4f in 79% (74% over two stages, Scheme 3, reaction 2). Due to the presence of two nitrate groups, compound 4f may be of interest as a potential NO donor [92] and a precursor of new nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds via nucleophilic substitution of –ONO2 groups.

Scheme 3: Synthetic utility and derivatization of synthesized coupling product 2f.

Scheme 3: Synthetic utility and derivatization of synthesized coupling product 2f.

To clarify the reaction mechanism, cyclic voltammetry (CV) studies were conducted. CV curves of cyclohexanone oxime (S1), 1-bromo-1-nitrosocyclohexane (S2), 1-chloro-1-nitrosocyclohexane (S3), 1-nitrosocyclohexyl acetate (S4), 1-nitro-1-nitrosocyclohexane (1c), 1-nitrosocyclohexane-1-carbonitrile (1i), 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a), and 2,2-dimethyl-5-nitro-5-nitroso-1,3-dioxane (1f) were recorded on a working glassy-carbon electrode in MeCN solution (Figure 1). Tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate was chosen as the supporting electrolyte.

![[1860-5397-21-211-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-211-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: CV-curves of 0.01 M solutions of a) 1a (blue), b) 1f (azure), c) 1c (pink), d) 1i (yellow), e) S4 (red), f) S3 (green), g) S2 (brown), and h) S1 (orange) in 0.1 M n-Bu4NBF4 solution in MeCN on a working glassy-carbon electrode (d = 3 mm) under a scan rate of 0.1 V/s at 298 K.

Figure 1: CV-curves of 0.01 M solutions of a) 1a (blue), b) 1f (azure), c) 1c (pink), d) 1i (yellow), e) S4 (...

As shown by the voltammograms of 0.01 M solutions of 1-nitro-1-nitroso compounds 1a, 1f, 1c, and 1i in MeCN, these substances do not undergo noticeable oxidation up to +2.4 V. On the other hand, 1-chloro-1-nitrosocyclohexane (S3, green curve) and 1-nitrosocyclohexyl acetate (S4, red curve) are oxidized at +1.82 V and +1.77 V, respectively. 1-Bromo-1-nitrosocyclohexane (S2, brown curve) exhibits a broad oxidation peak around +1.84 V, whereas cyclohexanone oxime (S1, orange curve) shows no significant oxidation up to +2.4 V. However, its reaction with ADN in the optimized reaction conditions resulted in a complex mixture of oxime oxidation products with full conversion of S1. The obtained data indicate that the presence of an electron-withdrawing group (NO2, CN) at the carbon atom geminal to the NO group prevents latter from facile oxidation, which, in turn, facilitate the desired nitro-NNO-azoxylation.

As previously demonstrated in our study [87], ADN exhibits two irreversible oxidation peaks (red curve) at +1.8 V and +2.1 V, which are higher than or comparable to those of S2–S4 (Figure 2).

![[1860-5397-21-211-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-211-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: CV-curves of 0.01 M solutions of a) 1a (blue), b) ADN (red), c) the mixture of 1a and ADN (green), d) 2a (pink) in 0.1 M n-Bu4NBF4 solution in MeCN on a working glassy-carbon electrode (d = 3 mm) under a scan rate of 0.1 V/s at 298 K.

Figure 2: CV-curves of 0.01 M solutions of a) 1a (blue), b) ADN (red), c) the mixture of 1a and ADN (green), ...

Upon the addition of ADN to a solution of 1a (Figure 2, green curve), a single oxidation peak was observed at +1.89 V. Finally, the reaction product nitro-NNO-azoxy propane 2a exhibits an oxidation peak at +1.68 V (Figure 2, pink curve). Despite the lower oxidation potential of 2a, we speculate that an excess of ADN suppresses competitive oxidation of the reaction product.

To gain insight into the reaction mechanism, control experiments were conducted (Scheme 4).

Discovered electrochemical coupling performed in a divided H-cell with 1a and ADN in anodic chamber (Scheme 4, reaction 1) afforded the corresponding nitro-NNO-azoxylation product 2a in a 69% yield. This result suggests that the process proceeds preferentially at anode surface. The studied reaction was also carried out under controlled potential conditions (Scheme 4, reaction 2) at E ≈ 1.8 V for 2.0 F per mol 1a. In this case, the formation of 2a was observed in a 68% yield.

To gain insight into the reaction mechanism of the discovered nitro-NNO-azoxylation process quantum chemical calculations were performed [93] on ωB97X-3c [94] /CPCM(MeCN) level of theory (Figure 3). Based on cyclic voltammetry data, control experiments, and our previous study, the mechanism of the electrochemical synthesis of nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds 2 was proposed (Figure 3, Scheme 5).

![[1860-5397-21-211-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-211-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Free energy diagram of possible interaction pathways between 1a and dinitramide-derived radical A according to ωB97X-3c [94]/CPCM(MeCN) level of theory. Free energies ΔG and activation free energies ΔG≠ are given in kcal/mol. Dashed lines correspond to spin-state-changing transformations that may have additional energy barriers (not estimated).

Figure 3: Free energy diagram of possible interaction pathways between 1a and dinitramide-derived radical A a...

Scheme 5: Proposed mechanism for electrochemical nitro-NNO-azoxylation of 1-nitro-1-nitroso compounds 1. Free energies ΔG and activation free energies ΔG≠ are given in kcal/mol.

Scheme 5: Proposed mechanism for electrochemical nitro-NNO-azoxylation of 1-nitro-1-nitroso compounds 1. Free...

The reaction starts from direct anodic oxidation of dinitramide anion with the formation of N-centered radical A. Monitoring of the reaction potential during electrolysis under standard conditions using a reference electrode revealed that the measured potential ranged from 2.2 V (at the start of the reaction) to 2.4 V (at the end of the reaction), which is sufficient to oxidize ADN. According to the performed calculations, competitive oxidation of 1a does not occur, which is confirmed by the obtained CV-data (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). According to DFT calculations, the reaction of N-radical A with 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a) is expected to be barrierless with the formation of N-oxyl radical B. The radical B undergoes very low-barrier (ΔG≠ 5.5 kcal/mol) fragmentation with the release of NO2 molecule and formation of the final product 2a. An alternative pathway for the formation of 2a is a direct NO2 extrusion from the N-centered radical A with the formation of the nitro-nitrene C [87]. This nitrene can exist in a singlet state (C-s) or triplet state (C-t), the latter being 5.3 kcal/mol more stable. The formation of more stable C-t from A is about 10.8 kcal/mol uphill. The barrier of C-t addition to A was not estimated, as this step requires the change in spin-state. However, unexpectedly we found that addition of higher energy singlet nitrene C-s to A is not barrierless (ΔG≠ 10.9 kcal/mol). Moreover, according to our calculations C-s can easily (ΔG≠ 5.7 kcal/mol) undergo unimolecular rearrangement to the dimer of nitric oxide (N2O2). These results allow us to think that the reaction pathway via nitrene C-s is less plausible compared to the interaction of radical A with 1a.

Aliphatic nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds as potential NO donors and their in vitro fungicidal activity

At the second part of our study, the synthesized nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds were tested for fungicidal activity against phytopathogenic fungi and for NO-release activity. Earlier we have demonstrated [87] that nitro-NNO-azoxy arenes were discovered as a novel class of fungicides, with in vitro activity against a broad range of phytopathogenic fungi that cause a global threat to crop production and public health [95-99]. Herein, the synthesized nitro-NNO-azoxy alkanes were screened for antifungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi representing several taxonomic classes: Venturia inaequalis (V.i., ascomycete causing the apple scab), Rhizoctonia solani (R.s., basidiomycete causing potato black scurf), Fusarium oxysporum (F.o., ascomycete affecting the vascular system of plants and inducing wilting), Fusarium moniliforme (F.m., ascomycete known also as Fusarium verticillioides in modern literature, important pathogen of maize), Bipolaris sorokiniana (B.s., ascomycete causing root rot and spot blotch), and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (S.s., ascomycete affecting sunflower, potato, and other cultures). The degree of mycelium growth inhibition on potato-sucrose agar amended with the studied compounds (30 mg/L) was used as the criterion for evaluating fungicidal activity. The commercially available fungicide triadimefon was used as a reference compound.

As can be seen from Table 2, among the tested compounds 2a–I, the highest fungicidal activity was demonstrated by 2i, which contains a nitrile substituent. It was the most active against five of six fungi, except S.s. The model compound 2-nitro-2-nitro-NNO-azoxy propane 2a showed superior activity compared to that of triadimefon against R.s. and F.m. The other synthesized compounds (2b–h and 3f) do not show significant fungicidal activity, except for dinitrate 4f, which was the most active against R.s. and B.s. The results from Table 2 indicate that the synthesized compounds 2a–i represent a potentially new class of fungicides with unforeseen mode of action, which makes them a promising starting point for the development of novel crop protection agents.

Table 2: In vitro fungicidal activity of the synthesized nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds 2a.

| Entry | Compound | Mycelium growth inhibition (%) | |||||

| V. i. | R. s. | F. o. | F. m. | B. s. | S. s. | ||

| 1 |

2a |

6 | 89 | 33 | 94 | 11 | 21 |

| 2 |

2b |

7 | 24 | 4 | 11 | 15 | 8 |

| 3 |

2c |

4 | 11 | 11 | 77 | 11 | 14 |

| 4 |

2d |

0 | 29 | 8 | 7 | 22 | 8 |

| 5 |

2e |

13 | 57 | 16 | 32 | 21 | 17 |

| 6 |

2f |

6 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 10 |

| 7 |

2g |

0 | 22 | 5 | 6 | 15 | 15 |

| 8 |

2h |

0 | 34 | 5 | 11 | 14 | 11 |

| 9 |

2i |

100 | 100 | 91 | 100 | 64 | 46 |

| 10 |

3f |

0 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 11 |

4f |

25 | 52 | 40 | 81 | 48 | 22 |

| 12 |

(±)-triadimefon (reference compound) |

41 | 43 | 77 | 87 | 44 | 61 |

aThe data on fungicidal activity exceeding the standard (triadimefon) are printed in bold. Concentration of compounds in nutrient medium 30 mg·L−1.

Finally, we investigated an ability to release NO for the synthesized aliphatic nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds (Figure 4).

![[1860-5397-21-211-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-211-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Assessment of the NO release from compounds 2a–i, 3f, and 4f.

Figure 4: Assessment of the NO release from compounds 2a–i, 3f, and 4f.

Well-known NO-donor compounds 3-carbamoyl-4-(hydroxymethyl)furoxan (CAS-1609) [100,101] and nitroglycerin (NG) [102] were used as reference agents. The NO2− assumed to be formed as a result of NO oxidation was quantified by Griess assay, which serves as a generally accepted tool to estimate the NO release. The amounts of NO2− generated from nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds at pH 7.4 and 37 °C (physiological conditions) for 1 h were estimated spectrophotometrically via Griess reaction. According to the Griess test results, all synthesized nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds released high fluxes of NO (36–137%) exceeding those of CAS-1609 (22.1%) and NG (15.3%). Interestingly, azoxy derivatives 2a–e,i showed NO-donor properties only in the presence of ʟ-cysteine proposing the thiol-dependent mechanism of NO release. At the same time, compounds 2f–h demonstrated moderate NO-donor properties in the absence of ʟ-cysteine, which can be associated with a more complex mechanism of NO release for these substances. Importantly, azoxy species 3f and 4f showed no difference in NO-donor properties irrespective of the presence of ʟ-cysteine. It should be noted that despite the fact that the Griess test is widely used for the estimation of NO-donor ability for various N,O-containing compound classes, this method is indirect and deeper studies of the NO-release by nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds are to be performed in the future. Overall, the synthesized nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds are capable of NO release in a wide range of concentrations which is useful for various biomedical insights [16,103-105].

Conclusion

In summary, a green, safe, atom- and step-efficient electrochemical protocol for the synthesis of nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds from nitrosoalkanes with electron-withdrawing groups using ammonium dinitramide (ADN) was developed. One of the key features of the sustainable design of discovered process is the usage of ADN as both an electrolyte and a reagent. The proposed approach is operationally simple and scalable and can be performed in an undivided cell under high current densities without a loss of selectivity. The use of ammonium dinitramide as a source of the [=N–NO2] group and an electrolyte eliminates the need for hazardous nitronium salts and allows the synthesis of nitro-NNO-azoxy compounds in a single step. The synthesized products demonstrated marked in vitro NO-donor ability and fungicidal activity against a broad range of phytopathogenic fungi.

Experimental

Although we have encountered no difficulties during preparation and handling of compounds described and used in this paper, they are explosive energetic materials which are sensitive to impact and friction. Mechanical actions of these energetic materials, involving scratching or scraping, must be avoided. Experimental procedures involving ammonium dinitramide impose a potential risk of detonation due to its photosensitivity and hygroscopic nature. Any manipulations must be carried out by using appropriate standard safety precautions.

1H, 13C, 14N NMR spectra were recorded with Bruker DRX-500 (500.1, 125.8, 36.1 MHz, respectively) and Bruker AV600 (600.1, 150.9, 43.4 MHz, respectively) spectrometers. Chemical shifts are reported in delta (δ) units, parts per million (ppm) downfield from internal TMS (1H, 13C) or external CH3NO2 (14N negative values of δN correspond to upfield shifts). The IR spectra were recorded with a Bruker ALPHA-T spectrometer in the range of 400–4000 cm−1 (resolution 2 cm−1) as pellets with KBr or as a thin layer. High-resolution ESI mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded with a Bruker micrOTOF II instrument. Silica gel 60 Merck (15–40 μm) was used for preparative column and thin-layer chromatography. Silica gel “Silpearl UV 254” was used for preparative column and thin-layer chromatography. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on Merck silica gel 60 F254 and “Silufol” TLC silica gel UV-254 aluminum sheets. All reagents were purchased from Acros and Sigma-Aldrich. Solvents were purified before use, according to standard procedures. All other reagents were used without further purification. Ammonium dinitramide (ADN) [106], 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a) [107], 1-nitro-1-nitrosocyclopentane (1b) [108], 1-nitro-1-nitrosocyclohexane (1c) [109], 2-nitro-2-nitroso-1,3-diphenylpropane (1e) [110], 2,2-dimethyl-5-nitro-5-nitroso-1,3-dioxane (1f) [111], methyl 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropanoate (1g) [112], ethyl 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropanoate (1h) [112], 1-nitrosocyclohexane-1-carbonitrile (1i) [113], were prepared according to the reported procedures.

General procedure for the optimization of the reaction conditions for the synthesis of 2-nitro-2-(nitro-NNO-azoxy)propane (2a) from 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a) (experimental details for Table 1): In a manner analogous to one described in [87], an undivided 10 mL electrochemical cell was equipped with a platinum plate, stainless steel, nickel, graphite, carbon felt, or glassy carbon plate anode (40 × 10 mm) and a platinum plate, platinum wire (d = 1 mm, l = 113 mm, ncoils = 9), stainless steel, nickel, graphite or glassy carbon plate cathode (40 × 10 mm), and connected to a DC regulated power supply. Electrodes were completely immersed in the solution given S = 4 cm2 of working surface. A solution of 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a, 0.5 mmol, 59 mg), and ammonium dinitramide (ADN) (1–5 equiv, 1–5 mmol, 62–310 mg) in 10 mL of MeCN, acetone, DMF, MeOH or HFIP was electrolyzed using constant current conditions (I = 15–240 mA) at 23–25 °C under magnetic stirring. After passing 1–3 F∙mol−1 of electricity (reaction time 7–161 min), electrodes were washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with H2O (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The yields of 2a were determined with the use of 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an internal standard. NMR and IR spectra of the obtained product 2a are similar to those reported previously [88].

Typical procedure for electrochemical synthesis of nitro-NNO-azoxy alkanes 2a–i (experimental details for Scheme 2): In a manner analogous to one described in [87], an undivided 10 mL electrochemical cell was equipped with a platinum plate anode (40 × 10 mm) and a platinum wire cathode, and connected to a DC regulated power supply. Electrodes were completely immersed in the solution given S = 4.0 cm2 of working anode surface. A mixture of 1-nitro-1-nitrosoalkane 1a–i (0.5 mmol, 59–135 mg), and ADN (4.0 equiv, 2.0 mmol, 248 mg) in MeCN (10 mL) was electrolyzed using constant current conditions (I = 60 mA) at 23–25 °C under magnetic stirring. After passing 2.0 F∙mol−1 of electricity (reaction time 27 min), electrodes were washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with H2O (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and solvent removed in vacuo. Products 2a–i were isolated by column chromatography on silica gel.

Procedure for gram scale electrochemical synthesis of 2f (experimental details for Scheme 3, reaction 1): In a manner analogous to one described in [87], an undivided 50 mL electrochemical cell was equipped with a platinum plate anode (30 × 15 mm, S = 4.5 cm2) and a platinum wire cathode, and connected to a DC regulated power supply. A solution of 2,2-dimethyl-5-nitro-5-nitroso-1,3-dioxane (1f, 6.0 mmol, 1.14 g) and ADN (4.0 equiv, 24.0 mmol, 2.97 g) in MeCN (50 mL) was electrolyzed using constant current conditions (I = 60 mA) at 23–25 °C under magnetic stirring. After passing 2.0 F∙mol–1 of electricity (reaction time 321 min), electrodes were washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with H2O (100 mL) and brine (100 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Product 2f (1.02 g, 4.8 mmol, 68%) was isolated by column chromatography on silica gel (Rf = 0.15, petroleum ether/ethyl acetate, 40:1).

Procedure for deprotection of 2f (experimental details for Scheme 3, reaction 2): Acetyl chloride (4.5 mL, 63.3 mmol) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of 2,2-dimethyl-5-nitro-5-(nitro-NNO-azoxy)-1,3-dioxane (2f, 1.00 g, 4.0 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) at 25 °C. After addition, the reaction mixture was stirred at this temperature for 24 h (the completion of reaction was monitored by TLC). Then the solvent was removed in vacuo at 40 °C. Product 3f (0.79 g, 3.76 mmol, 94%) was isolated by column chromatography on silica gel (Rf = 0.40, petroleum ether/ethyl acetate, 3:1).

Procedure for nitration of 3f (experimental details for Scheme 3, reaction 2): 2-Nitro-2-(nitro-NNO-azoxy)-1,3-propanediol 3f (0.63 g, 3.0 mmol) was added in portions to a mixture of acetic anhydride (3.4 mL, 36.0 mmol) and 100% nitric acid (0.6 mL, 13.2 mmol) at 0 °C, and the mixture was stirred at this temperature for 30 min. Then the reaction mixture was poured into ice-water (50 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with water (30 mL), brine (30 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and solvent removed in vacuo. Product 4f (0.71 g, 2.37 mmol, 79%) was isolated by column chromatography on silica gel (Rf = 0.55, petroleum ether/ethyl acetate, 5:1).

Reaction in divided electrochemical cell (experimental details for Scheme 4, reaction 1): In a manner analogous to one described in [87], a divided H-type electrochemical cell (volume of each compartment – 30 mL, divided with DuPont Nafion® N-117 membrane) was equipped with a platinum anode (30 × 15 mm) and a platinum wire cathode, and connected to a DC regulated power supply. Electrodes were completely immersed in the solution given S = 4.5 cm2 of working surface. A solution of 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a, 1.0 mmol, 118 mg) and ADN (4.0 equiv, 4.0 mmol, 496 mg) in MeCN (20 mL) was placed in the anodic compartment of the cell, and a solution of ADN (4.0 mmol, 496 mg) in MeCN (20 mL) was placed in the cathodic compartment of the cell. Solutions were electrolyzed using constant current conditions (I = 60 mA) at 23–25 °C under magnetic stirring. After passing 2.0 F/mol of electricity (reaction time 54 min), electrodes were washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 20 mL). The organic phases from anodic and cathodic compartments were separately evaporated under water-jet vacuum. The yield of 2a was determined according to 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an internal standard.

Reaction under constant potential electrolysis (experimental details for Scheme 4, reaction 2): In a manner analogous to one described in [87], an undivided 10 mL electrochemical cell was equipped with a platinum plate anode (30 × 15 mm), a platinum wire cathode, and reference Ag/AgNO3 electrode linked to the solution by a porous glass diaphragm, and connected to a computer-assisted potentiostat. Electrodes were completely immersed in the solution given S = 4.5 cm2 of working anode surface. A mixture of 2-nitro-2-nitrosopropane (1a, 0.5 mmol, 59 mg), and ADN (4.0 equiv., 2.0 mmol, 248 mg) in MeCN (10 mL) was electrolyzed using constant potential conditions (Ecell = 1.8 V vs Ag/AgNO3) at 23–25 °C under magnetic stirring. After passing 2.0 F per mol 1a of electricity, electrodes were washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with H2O (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and solvent removed in vacuo. The yield of 2a was determined according to 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an internal standard.

Computational details: DFT computations were performed for 1 atm. and 298.15 K in Orca 6.1.0 package [93]. Results were visualized in Chemcraft 1.8 program. For conformationally flexible structures, generation of conformational ensembles was performed by GOAT algorithm [114] implemented in Orca: for closed shell species it was made using GFN2-xTB method [115] and for open-shell species by native ORCA 6.1.0 spin-polarized variant of GFN2-xTB method (“Native-spGFN2-xTB” keyword). ALPB(MeCN) solvation model [116] was used in both cases. Bond length constraints were used for the generation of conformer ensembles of transition states in order to avoid optimization to starting reagent(s) or product(s). On the next step, most stable conformers were identified by re-optimization of generated conformers and vibrational analysis on ωB97X-3c [94]/CPCM(MeCN) level of theory (in the case of >15 conformers, 15 most stable according to GFN2-xTB were analyzed).

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: General information on materials and instruments, experimental procedures, and characterization data for all compounds, XRD of 2c, computational details, and copies of 1H, 13C, 14N, 1H,13C HSQC, and 1H,13C HMBC NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 6.8 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: Crystallographic information for compound 2c. | ||

| Format: CIF | Size: 782.5 KB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 3: CheckCIF report for the data of 2c. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 155.5 KB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Rosen, B. R.; Werner, E. W.; O’Brien, A. G.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5571–5574. doi:10.1021/ja5013323

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Blair, L. M.; Sperry, J. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 794–812. doi:10.1021/np400124n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kouklovsky, C. Vietnam J. Chem. 2020, 58, 20–28. doi:10.1002/vjch.201900174

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Waldman, A. J.; Ng, T. L.; Wang, P.; Balskus, E. P. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5784–5863. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00621

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cai, B.-G.; Empel, C.; Yao, W.-Z.; Koenigs, R. M.; Xuan, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312031. doi:10.1002/anie.202312031

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Murarka, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 1735–1753. doi:10.1002/adsc.201701615

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Budnikov, A. S.; Krylov, I. B.; Lastovko, A. V.; Yu, B.; Terent'ev, A. O. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202200262. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202200262

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krylov, I. B.; Segida, O. O.; Budnikov, A. S.; Terent'ev, A. O. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 2502–2528. doi:10.1002/adsc.202100058

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Davies, J.; Morcillo, S. P.; Douglas, J. J.; Leonori, D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12154–12163. doi:10.1002/chem.201801655

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H.-S.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.-L.; Sun, K.; Chen, X.-L.; Qu, L.-B.; Yu, B. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 1306–1323. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.100

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.-Q.; Feng, C. Synlett 2025, 36, 1135–1141. doi:10.1055/a-2504-3639

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hammoud, F.; Hijazi, A.; Schmitt, M.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 188, 111901. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2023.111901

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zlotin, S. G.; Churakov, A. M.; Dalinger, I. L.; Luk’yanov, O. A.; Makhova, N. N.; Sukhorukov, A. Y.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 2017, 27, 535–546. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2017.11.001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zlotin, S. G.; Churakov, A. M.; Egorov, M. P.; Fershtat, L. L.; Klenov, M. S.; Kuchurov, I. V.; Makhova, N. N.; Smirnov, G. A.; Tomilov, Y. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 2021, 31, 731–749. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2021.11.001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yount, J.; Piercey, D. G. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 8809–8840. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00935

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Fershtat, L. L.; Zhilin, E. S. Molecules 2021, 26, 5705. doi:10.3390/molecules26185705

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Muniz Carvalho, E.; Silva Sousa, E. H.; Bernardes‐Génisson, V.; Gonzaga de França Lopes, L. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 4316–4348. doi:10.1002/ejic.202100527

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Fei, X.; Liao, L.-S.; Fan, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 4501–4508. doi:10.1002/chem.201806314

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, H.; Jung, H.; Song, F.; Zhu, S.; Bai, Z.; Chen, D.; He, G.; Chang, S.; Chen, G. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 378–385. doi:10.1038/s41557-021-00650-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ryan, M. C.; Martinelli, J. R.; Stahl, S. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9074–9077. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b05245

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fritsche, R. F.; Theumer, G.; Kataeva, O.; Knölker, H.-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 549–553. doi:10.1002/anie.201610168

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, F.; Gerken, J. B.; Bates, D. M.; Kim, Y. J.; Stahl, S. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12349–12356. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c04626

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mankad, N. P.; Müller, P.; Peters, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4083–4085. doi:10.1021/ja910224c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhu, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, B.; Bai, Z.; He, G.; Chen, G.; Wang, H. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 6458–6467. doi:10.1039/d5sc00064e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ou, Y.; Yang, T.; Tang, N.; Yin, S.-F.; Kambe, N.; Qiu, R. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6417–6422. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02227

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vemuri, P. Y.; Patureau, F. W. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 3902–3907. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01034

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barbor, J. P.; Nair, V. N.; Sharp, K. R.; Lohrey, T. D.; Dibrell, S. E.; Shah, T. K.; Walsh, M. J.; Reisman, S. E.; Stoltz, B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15071–15077. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c04834

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tabey, A.; Vemuri, P. Y.; Patureau, F. W. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 14343–14352. doi:10.1039/d1sc03851f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, W.; Xu, J.; Yang, F.; Zeng, X. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 42, 1336. doi:10.6023/cjoc202111019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sampaio-Dias, I. E.; Silva-Reis, S. C.; Pires-Lima, B. L.; Correia, X. C.; Costa-Almeida, H. F. Synthesis 2022, 54, 2031–2036. doi:10.1055/a-1695-1095

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barriault, D.; Ly, H. M.; Allen, M. A.; Gill, M. A.; Beauchemin, A. M. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 8767–8772. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.4c00674

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hill, J.; Hettikankanamalage, A. A.; Crich, D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14820–14825. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c05991

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hill, J.; Crich, D. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6396–6400. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02215

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lesnikov, V. K.; Golovanov, I. S.; Nelyubina, Y. V.; Aksenova, S. A.; Sukhorukov, A. Y. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7673. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43530-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Banerjee, A.; Yamamoto, H. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2124–2129. doi:10.1039/c8sc04996c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yan, M.; Kawamata, Y.; Baran, P. S. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13230–13319. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wiebe, A.; Gieshoff, T.; Möhle, S.; Rodrigo, E.; Zirbes, M.; Waldvogel, S. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5594–5619. doi:10.1002/anie.201711060

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Waldvogel, S. R.; Janza, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7122–7123. doi:10.1002/anie.201405082

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Frontana-Uribe, B. A.; Little, R. D.; Ibanez, J. G.; Palma, A.; Vasquez-Medrano, R. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 2099. doi:10.1039/c0gc00382d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schäfer, H. J. Electrochemical Generation of Radicals. In Radicals in Organic Synthesis; Renaud, P.; Sibi, M. P., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2001; pp 250–297. doi:10.1002/9783527618293.ch14

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zeng, X. Chem. – Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402220. doi:10.1002/chem.202402220

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Titenkova, K.; Chaplygin, D. A.; Fershtat, L. L. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400395. doi:10.1002/celc.202400395

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; McCallum, T.; Fu, N. iScience 2020, 23, 101796. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101796

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shao, J.; Liu, J.; Mei, H.; Han, J. Tetrahedron 2025, 173, 134467. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2025.134467

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hou, Z.-W.; Xu, H.-C.; Wang, L. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2024, 44, 101447. doi:10.1016/j.coelec.2024.101447

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiang, H.; He, J.; Qian, W.; Qiu, M.; Xu, H.; Duan, W.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, C. Molecules 2023, 28, 857. doi:10.3390/molecules28020857

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, N.; Xu, H.-C. Green Synth. Catal. 2021, 2, 165–178. doi:10.1016/j.gresc.2021.03.002

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Xiong, P.; Xu, H.-C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 3339–3350. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00472

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Barskaya, I. Y.; Veber, S. L.; Suturina, E. A.; Sherin, P. S.; Maryunina, K. Y.; Artiukhova, N. A.; Tretyakov, E. V.; Sagdeev, R. Z.; Ovcharenko, V. I.; Gritsan, N. P.; Fedin, M. V. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 13108–13117. doi:10.1039/c7dt02719b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kathiravan, S.; Nicholls, I. A. Curr. Res. Green Sustainable Chem. 2024, 8, 100405. doi:10.1016/j.crgsc.2024.100405

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kurig, N.; Palkovits, R. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 7508–7517. doi:10.1039/d3gc02084c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ye, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ma, W.; Zhang, F. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 2524–2540. doi:10.1039/d3gc00175j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, R.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Xia, Y.; Abdukader, A.; Xue, F.; Jin, W.; Liu, C. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 14931–14935. doi:10.1002/chem.202102262

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Titenkova, K.; Chaplygin, D. A.; Fershtat, L. L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2025, 23, 4971–4976. doi:10.1039/d5ob00481k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Titenkova, K.; Turpakov, E. A.; Chaplygin, D. A.; Fershtat, L. L. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 4434–4438. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5c00784

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shuvaev, A. D.; Feoktistov, M. A.; Teslenko, F. E.; Fershtat, L. L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 5050–5060. doi:10.1002/adsc.202400761

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gieshoff, T.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9437–9440. doi:10.1002/anie.201603899

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gieshoff, T.; Kehl, A.; Schollmeyer, D.; Moeller, K. D.; Waldvogel, S. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12317–12324. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b07488

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Titenkova, K.; Shuvaev, A. D.; Teslenko, F. E.; Zhilin, E. S.; Fershtat, L. L. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 6686–6693. doi:10.1039/d3gc01601c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Y.; Ye, Z.; Chen, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4035–4039. doi:10.1039/c9gc01895f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kehl, A.; Gieshoff, T.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S. R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 590–593. doi:10.1002/chem.201705578

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, P.; Xu, H.-C. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 4177–4179. doi:10.1002/celc.201900080

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bieniek, J. C.; Grünewald, M.; Winter, J.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S. R. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8180–8186. doi:10.1039/d2sc01827f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lv, S.; Han, X.; Wang, J.-Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Ma, L.; Niu, L.; Gao, W.; Zhou, J.; Hu, W.; Cui, Y.; Chen, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11583–11590. doi:10.1002/anie.202001510

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sadatnabi, A.; Mohamadighader, N.; Nematollahi, D. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6488–6493. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02304

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chong, X.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, B. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 285–295. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwz146

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Breising, V. M.; Kayser, J. M.; Kehl, A.; Schollmeyer, D.; Liermann, J. C.; Waldvogel, S. R. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 4348–4351. doi:10.1039/d0cc01052a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Feng, E.; Hou, Z.; Xu, H. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 39, 1424. doi:10.6023/cjoc201812007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shah, H. U. R.; Ahmad, K.; Naseem, H. A.; Parveen, S.; Ashfaq, M.; Aziz, T.; Shaheen, S.; Babras, A.; Shahzad, A. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1244, 131181. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131181

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, M.-Y.; Tang, Y.-F.; Han, G.-Z. Molecules 2023, 28, 6741. doi:10.3390/molecules28186741

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nitro, Nitroso, Azo, Azoxy, and Diazonium Compounds, Azides, Triazenes, and Tetrazenes. In Category 5, Compounds with One Saturated Carbon Heteroatom Bond; Banert, K.; Shinkai, I., Eds.; Science of Synthesis, Vol. 41; Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010. doi:10.1055/sos-sd-041-00001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zlotin, S. G.; Luk'yanov, O. A. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1993, 62, 143–168. doi:10.1070/rc1993v062n02abeh000010

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Churakov, A. M.; Ioffe, S. L.; Tartakovskii, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 1996, 6, 20–22. doi:10.1070/mc1996v006n01abeh000560

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Churakov, A. M.; Semenov, S. E.; Ioffe, S. L.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1997, 46, 1042–1043. doi:10.1007/bf02496149

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Klenov, M. S.; Churakov, A. M.; Voronin, A. A.; Vinogradov, D. B.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2024, 73, 1473–1494. doi:10.1007/s11172-024-4269-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sheremetev, A. B.; Semenov, S. E.; Kuzmin, V. S.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Ioffe, S. L. Chem. – Eur. J. 1998, 4, 1023–1026. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(19980615)4:6%3c1023::aid-chem1023%3e3.0.co;2-r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, H.; Wang, B. Z.; Li, X. Z.; Tong, J. F.; Lai, W. P.; Fan, X. Z. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2013, 34, 686–688. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2013.34.2.686

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, D.; Pang, S. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 20806–20813. doi:10.1039/c4ta04716h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, H.; Zhao, F.-q.; Yu, Q.; Lai, W.; Wang, B. Chin. J. Energ. Mater. 2014, 22, 880–883. doi:10.11943/j.issn.1006-9941.2014.06.032

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lai, W.-p.; Lian, P.; Liu, Y.-z.; Yu, T.; Zhu, W.-l.; Ge, Z.-x.; Lv, J. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2479. doi:10.1007/s00894-014-2479-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Anikin, O. V.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Churakov, A. M.; Voronin, A. A.; Muravyev, N. V.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 4189–4195. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201900314

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Klenov, M. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Guskov, A. A.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2019, 68, 1798–1800. doi:10.1007/s11172-019-2628-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Anikin, O. V.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Voronin, A. A.; Lempert, D. B.; Muravyev, N. V.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Semenov, S. E.; Tartakovsky, V. A. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12243–12249. doi:10.1002/slct.202003182

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leonov, N. E.; Semenov, S. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Pivkina, A. N.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Lempert, D. B.; Kon'kova, T. S.; Matyushin, Y. N.; Miroshnichenko, E. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 2021, 31, 789–791. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2021.11.006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Churakov, A. M.; Konkova, T. S.; Miroshnichenko, E. A.; Matyushin, Y. N.; Muravyev, N. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 71, 1634–1640. doi:10.1007/s11172-022-3572-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scherschel, N. F.; Piercey, D. G. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 231935. doi:10.1098/rsos.231935

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] -

Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Anikin, O. V.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Monogarov, K. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 91–94. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201801533

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, H.-M.; Li, G.-X.; Li, L. Fuel 2023, 334, 126742. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.126742

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheng, J.; Cao, J.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Ouyang, K.; Rossi, C.; Ye, Y.; Shen, R. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144412. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.144412

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harimech, Z.; Toshtay, K.; Atamanov, M.; Azat, S.; Amrousse, R. Aerospace 2023, 10, 832. doi:10.3390/aerospace10100832

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chegaev, K.; Lazzarato, L.; Marcarino, P.; Di Stilo, A.; Fruttero, R.; Vanthuyne, N.; Roussel, C.; Gasco, A. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4020–4025. doi:10.1021/jm9002236

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 15, e70019. doi:10.1002/wcms.70019

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Müller, M.; Hansen, A.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 014103. doi:10.1063/5.0133026

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Xu, J. mLife 2022, 1, 223–240. doi:10.1002/mlf2.12036

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tleuova, A. B.; Wielogorska, E.; Talluri, V. S. S. L. P.; Štěpánek, F.; Elliott, C. T.; Grigoriev, D. O. J. Controlled Release 2020, 326, 468–481. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.035

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fisher, M. C.; Henk, D. A.; Briggs, C. J.; Brownstein, J. S.; Madoff, L. C.; McCraw, S. L.; Gurr, S. J. Nature 2012, 484, 186–194. doi:10.1038/nature10947

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Oerke, E.-C. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. doi:10.1017/s0021859605005708

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Brauer, V. S.; Rezende, C. P.; Pessoni, A. M.; De Paula, R. G.; Rangappa, K. S.; Nayaka, S. C.; Gupta, V. K.; Almeida, F. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 521. doi:10.3390/biom9100521

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bohn, H.; Brendel, J.; Martorana, P. A.; Schönafinger, K. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 114, 1605–1612. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14946.x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ustyuzhanina, N. E.; Fershtat, L. L.; Gening, M. L.; Nifantiev, N. E.; Makhova, N. N. Mendeleev Commun. 2018, 28, 49–51. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2018.01.016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuchurov, I. V.; Arabadzhi, S. S.; Zharkov, M. N.; Fershtat, L. L.; Zlotin, S. G. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2535–2540. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b04029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stebletsova, I. A.; Larin, A. A.; Matnurov, E. M.; Ananyev, I. V.; Babak, M. V.; Fershtat, L. L. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 230. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics17020230

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shuvaev, A. D.; Zhilin, E. S.; Fershtat, L. L. Synthesis 2023, 55, 1863–1874. doi:10.1055/a-2011-7264

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhilin, E. S.; Ustyuzhanina, N. E.; Fershtat, L. L.; Nifantiev, N. E.; Makhova, N. N. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022, 100, 1017–1024. doi:10.1111/cbdd.13918

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luk'yanov, O. A.; Gorelik, V. P.; Tartakovskii, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1994, 43, 89–92. doi:10.1007/bf00699142

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, X.; Deng, H.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Wang, X.; Liang, H.; Cheng, J.-P. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 4472–4478. doi:10.1021/jo900732b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rehse, K.; Herpel, M. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim, Ger.) 1998, 331, 79–84. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-4184(199802)331:2%3c79::aid-ardp79%3e3.0.co;2-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nametkin, S. S. Zh. Russ. Fiz.-Khim. O-va., Chast Khim. 1910, 42, 585–586.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Charlton, W.; Earl, J. C.; Kenner, J.; Luciano, A. A. J. Chem. Soc. 1932, 30. doi:10.1039/jr9320000030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luk'yanov, O. A.; Salamonov, Yu. B.; Bass, A. G.; Strelenko, Yu. A. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. (Engl. Transl.) 1991, 40, 93–98. doi:10.1007/bf00959638

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ungnade, H. E.; Kissinger, L. W. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 666–668. doi:10.1021/jo01087a026

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Pritzkow, W.; Rösler, W. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1967, 703, 66–76. doi:10.1002/jlac.19677030108

Return to citation in text: [1] -

de Souza, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202500393. doi:10.1002/anie.202500393

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bannwarth, C.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1652–1671. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01176

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ehlert, S.; Stahn, M.; Spicher, S.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4250–4261. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00471

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 92. | Chegaev, K.; Lazzarato, L.; Marcarino, P.; Di Stilo, A.; Fruttero, R.; Vanthuyne, N.; Roussel, C.; Gasco, A. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4020–4025. doi:10.1021/jm9002236 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 93. | Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 15, e70019. doi:10.1002/wcms.70019 |

| 102. | Kuchurov, I. V.; Arabadzhi, S. S.; Zharkov, M. N.; Fershtat, L. L.; Zlotin, S. G. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2535–2540. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b04029 |

| 16. | Fershtat, L. L.; Zhilin, E. S. Molecules 2021, 26, 5705. doi:10.3390/molecules26185705 |

| 103. | Stebletsova, I. A.; Larin, A. A.; Matnurov, E. M.; Ananyev, I. V.; Babak, M. V.; Fershtat, L. L. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 230. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics17020230 |

| 104. | Shuvaev, A. D.; Zhilin, E. S.; Fershtat, L. L. Synthesis 2023, 55, 1863–1874. doi:10.1055/a-2011-7264 |

| 105. | Zhilin, E. S.; Ustyuzhanina, N. E.; Fershtat, L. L.; Nifantiev, N. E.; Makhova, N. N. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022, 100, 1017–1024. doi:10.1111/cbdd.13918 |

| 95. | Xu, J. mLife 2022, 1, 223–240. doi:10.1002/mlf2.12036 |

| 96. | Tleuova, A. B.; Wielogorska, E.; Talluri, V. S. S. L. P.; Štěpánek, F.; Elliott, C. T.; Grigoriev, D. O. J. Controlled Release 2020, 326, 468–481. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.035 |

| 97. | Fisher, M. C.; Henk, D. A.; Briggs, C. J.; Brownstein, J. S.; Madoff, L. C.; McCraw, S. L.; Gurr, S. J. Nature 2012, 484, 186–194. doi:10.1038/nature10947 |

| 98. | Oerke, E.-C. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. doi:10.1017/s0021859605005708 |

| 99. | Brauer, V. S.; Rezende, C. P.; Pessoni, A. M.; De Paula, R. G.; Rangappa, K. S.; Nayaka, S. C.; Gupta, V. K.; Almeida, F. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 521. doi:10.3390/biom9100521 |

| 100. | Bohn, H.; Brendel, J.; Martorana, P. A.; Schönafinger, K. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 114, 1605–1612. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14946.x |

| 101. | Ustyuzhanina, N. E.; Fershtat, L. L.; Gening, M. L.; Nifantiev, N. E.; Makhova, N. N. Mendeleev Commun. 2018, 28, 49–51. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2018.01.016 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 94. | Müller, M.; Hansen, A.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 014103. doi:10.1063/5.0133026 |

| 94. | Müller, M.; Hansen, A.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 014103. doi:10.1063/5.0133026 |

| 106. | Luk'yanov, O. A.; Gorelik, V. P.; Tartakovskii, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1994, 43, 89–92. doi:10.1007/bf00699142 |

| 107. | Li, X.; Deng, H.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Wang, X.; Liang, H.; Cheng, J.-P. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 4472–4478. doi:10.1021/jo900732b |

| 108. | Rehse, K.; Herpel, M. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim, Ger.) 1998, 331, 79–84. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-4184(199802)331:2%3c79::aid-ardp79%3e3.0.co;2-9 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 88. | Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Anikin, O. V.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Monogarov, K. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 91–94. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201801533 |

| 112. | Ungnade, H. E.; Kissinger, L. W. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 666–668. doi:10.1021/jo01087a026 |

| 113. | Pritzkow, W.; Rösler, W. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1967, 703, 66–76. doi:10.1002/jlac.19677030108 |

| 111. | Luk'yanov, O. A.; Salamonov, Yu. B.; Bass, A. G.; Strelenko, Yu. A. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. (Engl. Transl.) 1991, 40, 93–98. doi:10.1007/bf00959638 |

| 112. | Ungnade, H. E.; Kissinger, L. W. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 666–668. doi:10.1021/jo01087a026 |

| 110. | Charlton, W.; Earl, J. C.; Kenner, J.; Luciano, A. A. J. Chem. Soc. 1932, 30. doi:10.1039/jr9320000030 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 1. | Rosen, B. R.; Werner, E. W.; O’Brien, A. G.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5571–5574. doi:10.1021/ja5013323 |

| 2. | Blair, L. M.; Sperry, J. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 794–812. doi:10.1021/np400124n |

| 3. | Kouklovsky, C. Vietnam J. Chem. 2020, 58, 20–28. doi:10.1002/vjch.201900174 |

| 4. | Waldman, A. J.; Ng, T. L.; Wang, P.; Balskus, E. P. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5784–5863. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00621 |

| 16. | Fershtat, L. L.; Zhilin, E. S. Molecules 2021, 26, 5705. doi:10.3390/molecules26185705 |

| 17. | Muniz Carvalho, E.; Silva Sousa, E. H.; Bernardes‐Génisson, V.; Gonzaga de França Lopes, L. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 4316–4348. doi:10.1002/ejic.202100527 |

| 1. | Rosen, B. R.; Werner, E. W.; O’Brien, A. G.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5571–5574. doi:10.1021/ja5013323 |

| 64. | Lv, S.; Han, X.; Wang, J.-Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Ma, L.; Niu, L.; Gao, W.; Zhou, J.; Hu, W.; Cui, Y.; Chen, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11583–11590. doi:10.1002/anie.202001510 |

| 65. | Sadatnabi, A.; Mohamadighader, N.; Nematollahi, D. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6488–6493. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02304 |

| 66. | Chong, X.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, B. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 285–295. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwz146 |

| 67. | Breising, V. M.; Kayser, J. M.; Kehl, A.; Schollmeyer, D.; Liermann, J. C.; Waldvogel, S. R. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 4348–4351. doi:10.1039/d0cc01052a |

| 68. | Feng, E.; Hou, Z.; Xu, H. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 39, 1424. doi:10.6023/cjoc201812007 |

| 13. | Zlotin, S. G.; Churakov, A. M.; Dalinger, I. L.; Luk’yanov, O. A.; Makhova, N. N.; Sukhorukov, A. Y.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 2017, 27, 535–546. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2017.11.001 |

| 14. | Zlotin, S. G.; Churakov, A. M.; Egorov, M. P.; Fershtat, L. L.; Klenov, M. S.; Kuchurov, I. V.; Makhova, N. N.; Smirnov, G. A.; Tomilov, Y. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 2021, 31, 731–749. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2021.11.001 |

| 15. | Yount, J.; Piercey, D. G. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 8809–8840. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00935 |

| 69. | Shah, H. U. R.; Ahmad, K.; Naseem, H. A.; Parveen, S.; Ashfaq, M.; Aziz, T.; Shaheen, S.; Babras, A.; Shahzad, A. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1244, 131181. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131181 |

| 70. | Zhao, M.-Y.; Tang, Y.-F.; Han, G.-Z. Molecules 2023, 28, 6741. doi:10.3390/molecules28186741 |

| 12. | Hammoud, F.; Hijazi, A.; Schmitt, M.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 188, 111901. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2023.111901 |

| 52. | Ye, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ma, W.; Zhang, F. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 2524–2540. doi:10.1039/d3gc00175j |

| 53. | Wang, R.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Xia, Y.; Abdukader, A.; Xue, F.; Jin, W.; Liu, C. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 14931–14935. doi:10.1002/chem.202102262 |

| 116. | Ehlert, S.; Stahn, M.; Spicher, S.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4250–4261. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00471 |

| 5. | Cai, B.-G.; Empel, C.; Yao, W.-Z.; Koenigs, R. M.; Xuan, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312031. doi:10.1002/anie.202312031 |

| 6. | Murarka, S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 1735–1753. doi:10.1002/adsc.201701615 |

| 7. | Budnikov, A. S.; Krylov, I. B.; Lastovko, A. V.; Yu, B.; Terent'ev, A. O. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202200262. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202200262 |

| 8. | Krylov, I. B.; Segida, O. O.; Budnikov, A. S.; Terent'ev, A. O. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 2502–2528. doi:10.1002/adsc.202100058 |

| 9. | Davies, J.; Morcillo, S. P.; Douglas, J. J.; Leonori, D. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12154–12163. doi:10.1002/chem.201801655 |

| 10. | Wang, H.-S.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.-L.; Sun, K.; Chen, X.-L.; Qu, L.-B.; Yu, B. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 1306–1323. doi:10.3762/bjoc.21.100 |

| 11. | Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.-Q.; Feng, C. Synlett 2025, 36, 1135–1141. doi:10.1055/a-2504-3639 |

| 42. | Titenkova, K.; Chaplygin, D. A.; Fershtat, L. L. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400395. doi:10.1002/celc.202400395 |

| 54. | Titenkova, K.; Chaplygin, D. A.; Fershtat, L. L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2025, 23, 4971–4976. doi:10.1039/d5ob00481k |

| 55. | Titenkova, K.; Turpakov, E. A.; Chaplygin, D. A.; Fershtat, L. L. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 4434–4438. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5c00784 |

| 56. | Shuvaev, A. D.; Feoktistov, M. A.; Teslenko, F. E.; Fershtat, L. L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 5050–5060. doi:10.1002/adsc.202400761 |

| 57. | Gieshoff, T.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9437–9440. doi:10.1002/anie.201603899 |

| 58. | Gieshoff, T.; Kehl, A.; Schollmeyer, D.; Moeller, K. D.; Waldvogel, S. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12317–12324. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b07488 |

| 59. | Titenkova, K.; Shuvaev, A. D.; Teslenko, F. E.; Zhilin, E. S.; Fershtat, L. L. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 6686–6693. doi:10.1039/d3gc01601c |

| 60. | Li, Y.; Ye, Z.; Chen, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4035–4039. doi:10.1039/c9gc01895f |

| 61. | Kehl, A.; Gieshoff, T.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S. R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 590–593. doi:10.1002/chem.201705578 |

| 62. | Xu, P.; Xu, H.-C. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 4177–4179. doi:10.1002/celc.201900080 |

| 63. | Bieniek, J. C.; Grünewald, M.; Winter, J.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S. R. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8180–8186. doi:10.1039/d2sc01827f |

| 94. | Müller, M.; Hansen, A.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 014103. doi:10.1063/5.0133026 |

| 36. | Yan, M.; Kawamata, Y.; Baran, P. S. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13230–13319. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397 |

| 37. | Wiebe, A.; Gieshoff, T.; Möhle, S.; Rodrigo, E.; Zirbes, M.; Waldvogel, S. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5594–5619. doi:10.1002/anie.201711060 |

| 38. | Waldvogel, S. R.; Janza, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7122–7123. doi:10.1002/anie.201405082 |

| 39. | Frontana-Uribe, B. A.; Little, R. D.; Ibanez, J. G.; Palma, A.; Vasquez-Medrano, R. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 2099. doi:10.1039/c0gc00382d |

| 15. | Yount, J.; Piercey, D. G. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 8809–8840. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00935 |

| 42. | Titenkova, K.; Chaplygin, D. A.; Fershtat, L. L. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400395. doi:10.1002/celc.202400395 |

| 47. | Chen, N.; Xu, H.-C. Green Synth. Catal. 2021, 2, 165–178. doi:10.1016/j.gresc.2021.03.002 |

| 48. | Xiong, P.; Xu, H.-C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 3339–3350. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00472 |

| 114. | de Souza, B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202500393. doi:10.1002/anie.202500393 |

| 30. | Sampaio-Dias, I. E.; Silva-Reis, S. C.; Pires-Lima, B. L.; Correia, X. C.; Costa-Almeida, H. F. Synthesis 2022, 54, 2031–2036. doi:10.1055/a-1695-1095 |

| 31. | Barriault, D.; Ly, H. M.; Allen, M. A.; Gill, M. A.; Beauchemin, A. M. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 8767–8772. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.4c00674 |

| 32. | Hill, J.; Hettikankanamalage, A. A.; Crich, D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14820–14825. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c05991 |

| 33. | Hill, J.; Crich, D. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6396–6400. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02215 |

| 34. | Lesnikov, V. K.; Golovanov, I. S.; Nelyubina, Y. V.; Aksenova, S. A.; Sukhorukov, A. Y. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7673. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43530-6 |

| 35. | Banerjee, A.; Yamamoto, H. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2124–2129. doi:10.1039/c8sc04996c |

| 50. | Kathiravan, S.; Nicholls, I. A. Curr. Res. Green Sustainable Chem. 2024, 8, 100405. doi:10.1016/j.crgsc.2024.100405 |

| 51. | Kurig, N.; Palkovits, R. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 7508–7517. doi:10.1039/d3gc02084c |

| 115. | Bannwarth, C.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1652–1671. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01176 |

| 1. | Rosen, B. R.; Werner, E. W.; O’Brien, A. G.; Baran, P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5571–5574. doi:10.1021/ja5013323 |

| 5. | Cai, B.-G.; Empel, C.; Yao, W.-Z.; Koenigs, R. M.; Xuan, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312031. doi:10.1002/anie.202312031 |

| 19. | Wang, H.; Jung, H.; Song, F.; Zhu, S.; Bai, Z.; Chen, D.; He, G.; Chang, S.; Chen, G. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 378–385. doi:10.1038/s41557-021-00650-0 |

| 20. | Ryan, M. C.; Martinelli, J. R.; Stahl, S. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9074–9077. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b05245 |

| 21. | Fritsche, R. F.; Theumer, G.; Kataeva, O.; Knölker, H.-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 549–553. doi:10.1002/anie.201610168 |

| 22. | Wang, F.; Gerken, J. B.; Bates, D. M.; Kim, Y. J.; Stahl, S. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12349–12356. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c04626 |

| 23. | Mankad, N. P.; Müller, P.; Peters, J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4083–4085. doi:10.1021/ja910224c |

| 24. | Zhu, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, B.; Bai, Z.; He, G.; Chen, G.; Wang, H. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 6458–6467. doi:10.1039/d5sc00064e |

| 25. | Ou, Y.; Yang, T.; Tang, N.; Yin, S.-F.; Kambe, N.; Qiu, R. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6417–6422. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02227 |

| 26. | Vemuri, P. Y.; Patureau, F. W. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 3902–3907. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01034 |

| 27. | Barbor, J. P.; Nair, V. N.; Sharp, K. R.; Lohrey, T. D.; Dibrell, S. E.; Shah, T. K.; Walsh, M. J.; Reisman, S. E.; Stoltz, B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15071–15077. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c04834 |

| 28. | Tabey, A.; Vemuri, P. Y.; Patureau, F. W. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 14343–14352. doi:10.1039/d1sc03851f |

| 29. | Zhao, W.; Xu, J.; Yang, F.; Zeng, X. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 42, 1336. doi:10.6023/cjoc202111019 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 18. | Liu, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Fei, X.; Liao, L.-S.; Fan, J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 4501–4508. doi:10.1002/chem.201806314 |

| 40. | Schäfer, H. J. Electrochemical Generation of Radicals. In Radicals in Organic Synthesis; Renaud, P.; Sibi, M. P., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2001; pp 250–297. doi:10.1002/9783527618293.ch14 |

| 41. | Zeng, X. Chem. – Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402220. doi:10.1002/chem.202402220 |

| 42. | Titenkova, K.; Chaplygin, D. A.; Fershtat, L. L. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400395. doi:10.1002/celc.202400395 |

| 43. | Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; McCallum, T.; Fu, N. iScience 2020, 23, 101796. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101796 |

| 44. | Shao, J.; Liu, J.; Mei, H.; Han, J. Tetrahedron 2025, 173, 134467. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2025.134467 |

| 45. | Hou, Z.-W.; Xu, H.-C.; Wang, L. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2024, 44, 101447. doi:10.1016/j.coelec.2024.101447 |

| 46. | Xiang, H.; He, J.; Qian, W.; Qiu, M.; Xu, H.; Duan, W.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, C. Molecules 2023, 28, 857. doi:10.3390/molecules28020857 |

| 47. | Chen, N.; Xu, H.-C. Green Synth. Catal. 2021, 2, 165–178. doi:10.1016/j.gresc.2021.03.002 |

| 48. | Xiong, P.; Xu, H.-C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 3339–3350. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00472 |

| 49. | Barskaya, I. Y.; Veber, S. L.; Suturina, E. A.; Sherin, P. S.; Maryunina, K. Y.; Artiukhova, N. A.; Tretyakov, E. V.; Sagdeev, R. Z.; Ovcharenko, V. I.; Gritsan, N. P.; Fedin, M. V. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 13108–13117. doi:10.1039/c7dt02719b |

| 93. | Neese, F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2025, 15, e70019. doi:10.1002/wcms.70019 |

| 76. | Sheremetev, A. B.; Semenov, S. E.; Kuzmin, V. S.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Ioffe, S. L. Chem. – Eur. J. 1998, 4, 1023–1026. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(19980615)4:6%3c1023::aid-chem1023%3e3.0.co;2-r |

| 77. | Li, H.; Wang, B. Z.; Li, X. Z.; Tong, J. F.; Lai, W. P.; Fan, X. Z. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2013, 34, 686–688. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2013.34.2.686 |

| 78. | Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, D.; Pang, S. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 20806–20813. doi:10.1039/c4ta04716h |

| 79. | Li, H.; Zhao, F.-q.; Yu, Q.; Lai, W.; Wang, B. Chin. J. Energ. Mater. 2014, 22, 880–883. doi:10.11943/j.issn.1006-9941.2014.06.032 |

| 80. | Lai, W.-p.; Lian, P.; Liu, Y.-z.; Yu, T.; Zhu, W.-l.; Ge, Z.-x.; Lv, J. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2479. doi:10.1007/s00894-014-2479-y |

| 81. | Anikin, O. V.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Churakov, A. M.; Voronin, A. A.; Muravyev, N. V.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 4189–4195. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201900314 |

| 82. | Klenov, M. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Guskov, A. A.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2019, 68, 1798–1800. doi:10.1007/s11172-019-2628-7 |

| 83. | Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Anikin, O. V.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Voronin, A. A.; Lempert, D. B.; Muravyev, N. V.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Semenov, S. E.; Tartakovsky, V. A. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12243–12249. doi:10.1002/slct.202003182 |

| 84. | Leonov, N. E.; Semenov, S. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Pivkina, A. N.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Lempert, D. B.; Kon'kova, T. S.; Matyushin, Y. N.; Miroshnichenko, E. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 2021, 31, 789–791. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2021.11.006 |

| 85. | Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Churakov, A. M.; Konkova, T. S.; Miroshnichenko, E. A.; Matyushin, Y. N.; Muravyev, N. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 71, 1634–1640. doi:10.1007/s11172-022-3572-5 |

| 86. | Scherschel, N. F.; Piercey, D. G. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 231935. doi:10.1098/rsos.231935 |

| 5. | Cai, B.-G.; Empel, C.; Yao, W.-Z.; Koenigs, R. M.; Xuan, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312031. doi:10.1002/anie.202312031 |

| 71. | Nitro, Nitroso, Azo, Azoxy, and Diazonium Compounds, Azides, Triazenes, and Tetrazenes. In Category 5, Compounds with One Saturated Carbon Heteroatom Bond; Banert, K.; Shinkai, I., Eds.; Science of Synthesis, Vol. 41; Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010. doi:10.1055/sos-sd-041-00001 |

| 72. | Zlotin, S. G.; Luk'yanov, O. A. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1993, 62, 143–168. doi:10.1070/rc1993v062n02abeh000010 |

| 73. | Churakov, A. M.; Ioffe, S. L.; Tartakovskii, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 1996, 6, 20–22. doi:10.1070/mc1996v006n01abeh000560 |

| 74. | Churakov, A. M.; Semenov, S. E.; Ioffe, S. L.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1997, 46, 1042–1043. doi:10.1007/bf02496149 |

| 75. | Klenov, M. S.; Churakov, A. M.; Voronin, A. A.; Vinogradov, D. B.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2024, 73, 1473–1494. doi:10.1007/s11172-024-4269-8 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 89. | Li, H.-M.; Li, G.-X.; Li, L. Fuel 2023, 334, 126742. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.126742 |

| 90. | Cheng, J.; Cao, J.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Ouyang, K.; Rossi, C.; Ye, Y.; Shen, R. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144412. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.144412 |

| 91. | Harimech, Z.; Toshtay, K.; Atamanov, M.; Azat, S.; Amrousse, R. Aerospace 2023, 10, 832. doi:10.3390/aerospace10100832 |

| 74. | Churakov, A. M.; Semenov, S. E.; Ioffe, S. L.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1997, 46, 1042–1043. doi:10.1007/bf02496149 |

| 74. | Churakov, A. M.; Semenov, S. E.; Ioffe, S. L.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1997, 46, 1042–1043. doi:10.1007/bf02496149 |

| 73. | Churakov, A. M.; Ioffe, S. L.; Tartakovskii, V. A. Mendeleev Commun. 1996, 6, 20–22. doi:10.1070/mc1996v006n01abeh000560 |

| 74. | Churakov, A. M.; Semenov, S. E.; Ioffe, S. L.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1997, 46, 1042–1043. doi:10.1007/bf02496149 |

| 87. | Budnikov, A. S.; Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Shevchenko, M. I.; Dvinyaninova, T. Y.; Krylov, I. B.; Churakov, A. M.; Fedyanin, I. V.; Tartakovsky, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. doi:10.3390/molecules29235563 |

| 88. | Leonov, N. E.; Klenov, M. S.; Anikin, O. V.; Churakov, A. M.; Strelenko, Y. A.; Monogarov, K. A.; Tartakovsky, V. A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 91–94. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201801533 |

© 2025 Budnikov et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.