Abstract

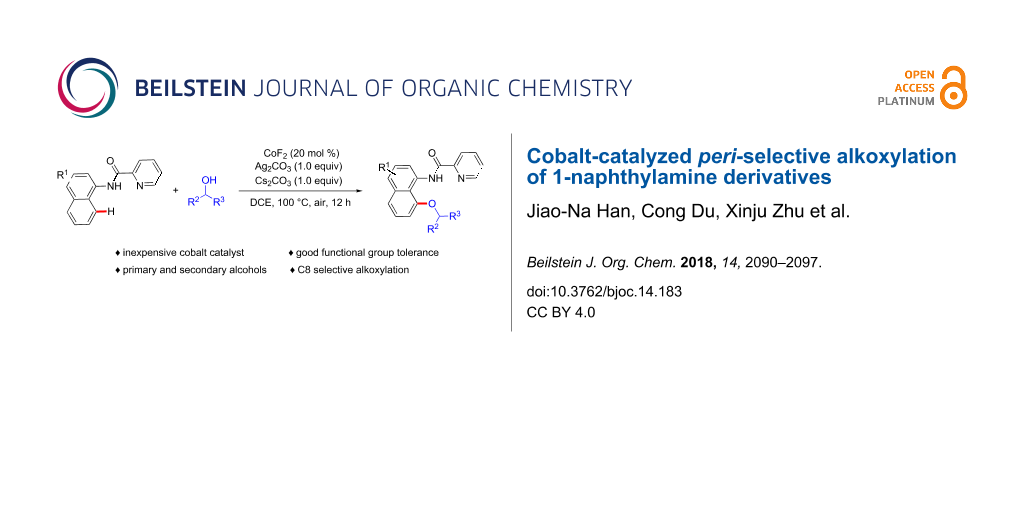

A cobalt-catalyzed C(sp2)–H alkoxylation of 1-naphthylamine derivatives has been disclosed, which represents an efficient approach to synthesize aryl ethers with broad functional group tolerance. It is noteworthy that secondary alcohols, such as hexafluoroisopropanol, isopropanol, isobutanol, and isopentanol, were well tolerated under the current catalytic system. Moreover, a series of biologically relevant fluorine-aryl ethers were easily obtained under mild reaction conditions after the removal of the directing group.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Aryl ethers are common structural units present in many natural products, functional materials, and pharmaceuticals [1]. Consequently, a variety of strategies have emerged to access them, including Pd-catalyzed and Cu-catalyzed coupling reactions (Buchwald–Harting couplings and Ullmann reactions) [2-4]. However, these classic methods always possess some limitations such as preactivated starting materials, poor regioselectivities, and tedious steps [5]. Therefore, it is desirable to develop an effective strategy to achieve this transformation [6,7].

Over the past few decades, transition-metal-catalyzed C–H activation to form C–C or C–heteroatom bonds has attracted more attention [8-13]. In particular, the formation of C–O bonds is widely used in the syntheses of pharmaceuticals and functional materials [14-17]. The direct hydroxylation [18,19] and acetoxylation [20-22] have been developed rapidly in recent years. By contrast, alkoxylation or phenoxylation confronts great challenges because alkanols or phenols are easily converted into the corresponding aldehydes, ketones, or carboxylic acids [7,23-25]. Recently, Gooßen [26,27], Sanford [28], Song, [29,30] and others [31-42] have successfully reported alkoxylation reactions with the auxiliary of directing groups. However, the transition-metal-catalyzed C–H alkoxylation is still largely limited to palladium- [28,33-40] or copper- [26,27,29,41,42] catalyzed systems. Recently, the inexpensive cobalt catalysts have received significant attention because of their unique and versatile activities in the C–H functionalizations [43-51]. In 2015, the cobalt-catalyzed alkoxylation of aromatic (and olefinic) carboxamides with primary alcohols was first reported by the Niu and Song group (Figure 1a) [30]. Successively, Ackermann realized the electrochemical cobalt-catalyzed alkoxylation via a similar process (Figure 1b) [32]. However, cobalt-catalyzed directed coupling of arenes with secondary alcohols has not been reported so far. Herein, we explored a simple and facile protocol for cobalt-catalyzed picolinamide-directed alkoxylation of 1-naphthylamine derivatives with alcohols (Figure 1c).

Figure 1: Strategies for cobalt-catalyzed alkoxylation.

Figure 1: Strategies for cobalt-catalyzed alkoxylation.

Results and Discussion

Initially, N-(naphthalen-1-yl)picolinamide (1a) and hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP, 2a) were chosen as the model substrates to optimize the alkoxylation reaction (Table 1, see more in Tables S1–S5 in Supporting Information File 1). To our delight, the desired product 3aa was obtained in 66% yield when using Co(OAc)2·4H2O as catalyst and Ag2CO3 as oxidant (Table 1, entry 1). Other cobalt salts such as CoF3 and CoF2 were also employed as metal catalysts for C8 alkoxylation of 1a, and CoF2 was proved to be the optimal catalyst, affording 3aa in 71% yield (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). Subsequently, various bases such as Na2CO3, K2CO3, and Cs2CO3 were screened (Table 1, entries 4–6), which indicated that Cs2CO3 was most effective and the alkoxylated product 3aa could be isolated in 82% yield. Next, the effect of oxidants on the reactivity was investigated, and Ag2CO3 showed a superior result compared with alternative oxidants (Table 1, entries 6–8). Moreover, DCE and HFIP as co-solvents demonstrated higher reactivity, resulting in a slightly increased yield in 84% (Table 1, entries 9–11). Finally, variation of the reaction temperature did not promote the reaction efficiency.

Table 1: Optimization of the reaction conditions.a

|

|

||||

| entry | catalyst | base | oxidant | yield (%) |

| 1 | Co(OAc)2·4H2O | t-AmONa | Ag2CO3 | 66 |

| 2 | CoF3 | t-AmONa | Ag2CO3 | 60 |

| 3 | CoF2 | t-AmONa | Ag2CO3 | 71 |

| 4 | CoF2 | Na2CO3 | Ag2CO3 | 58 |

| 5 | CoF2 | K2CO3 | Ag2CO3 | 67 |

| 6 | CoF2 | Cs2CO3 | Ag2CO3 | 82 |

| 7 | CoF2 | Cs2CO3 | AgNO3 | 11 |

| 8 | CoF2 | Cs2CO3 | Ag2O | 32 |

| 9b | CoF2 | Cs2CO3 | Ag2CO3 | 84 |

| 10c | CoF2 | Cs2CO3 | Ag2CO3 | 80 |

| 11d | CoF2 | Cs2CO3 | Ag2CO3 | 77 |

aReaction conditions: 1a (0.2 mmol), 2a (1.0 mL), Co-catalyst (20 mol %), oxidant (1.0 equiv), base (1.0 equiv), 100 °C, air, 12 h. bDCE (1.0 mL) as co-solvent. cPhCF3 (1.0 mL) as co-solvent. dPhF (1.0 mL) as co-solvent. DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane.

With the established alkoxylated protocol in hand, the substrate scope of 1-naphthylamine derivatives was explored as shown in Scheme 1. Halogenated naphthylamines could afford the target products in 86–88% yields (3ba–3ca). Nitro- (1d) and benzenesulfonyl- (1e) substituted naphthylamines were found to proceed smoothly via this strategy (61–64%). In addition, a disubstituted naphthylamine provided the alkoxylated product in 47% yield (3fa). Moreover, a Boc amino group at C5 of the substrate 1g was also compatible with the transformation (33%). When a methoxy group was located at the C7 site of the naphthylamine, sterically hindered product 3ha was obtained in 81%. Besides, some benzylamine derivatives (N-(1-phenylethyl)picolinamide and N-benzhydrylpicolinamide) were attempted. However, no desired product could be detected.

Scheme 1: Reaction scope with respect to N-(naphthalen-1-yl)picolinamide derivatives. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol), 2a (1.0 mL), CoF2 (20 mol %), Ag2CO3 (1.0 equiv), Cs2CO3 (1.0 equiv), DCE (1.0 mL), 100 °C, air, 12 h.

Scheme 1: Reaction scope with respect to N-(naphthalen-1-yl)picolinamide derivatives. Reaction conditions: 1 ...

Next, the substrate scope of alcohols was investigated. As shown in Scheme 2, both primary and secondary alcohols were compatible with the slightly modified optimized conditions. A variety of fluoro-substituted alcohols 2a–e proceeded smoothly to afford the corresponding products in moderate to good yields (66–84%). Simple primary alkyl alcohols were well tolerated to provide the desired products in 54–84% yields (3af–ak). Also, the branched alcohols 2l, 2m, and 2n were employed to afford the corresponding products in 66–89% yields. Cyclopropylmethanol (2o), cyclohexylmethanol (2p), and adamantanemethanol (2q) were compatible with the transformation (45–56%). Moreover, an aliphatic ether and benzyl alcohol were proved to be effective coupling partners to provide 3ar and 3as in 68% and 70% yields, respectively. Compared with Co-catalyzed alkoxylation of arenes with primary alcohols [30,31], HFIP (2a), isopropanol (2t), isobutanol (2u), and isopentanol (2v) could all proceed smoothly to deliver the alkoxylated products in 58–89% yields. Furthermore, we attempted some tertiary alcohols (tert-butanol and 2-methyl-2-butanol). However, no desired product could be detected.

Scheme 2: Reaction scope with respect to alcohols. Reaction conditions: 1a (0.2 mmol), 2 (1.0 mL), CoF2 (20 mol %), Ag2CO3 (1.0 equiv), Cs2CO3 (1.0 equiv), DCE (1.0 mL), 110 °C, air, 24 h. a2q or 2s (5.0 equiv). b48 h.

Scheme 2: Reaction scope with respect to alcohols. Reaction conditions: 1a (0.2 mmol), 2 (1.0 mL), CoF2 (20 m...

In order to study the reaction mechanism, a series of control experiments were carried out (Scheme 3, see more details in Supporting Information File 1). In the absence of cobalt salt, no product was obtained under the standard reaction conditions. Under an argon atmosphere and without Ag2CO3, the product was isolated in 12% yield when a stoichiometric amount of CoF3 was introduced, whereas no product was obtained in the presence of CoF2 (Scheme 3, reaction 1). These results imply that the reaction should initiates from a CoIII species. The addition of a radical quencher, benzoquinone (BQ), suppressed the formation of product 3aa. When 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxyl (TEMPO) or 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT) was added under the standard reaction conditions, a significantly reduced yield (39% or 23%) was obtained (Scheme 3, reaction 2). These facts suggest that a radical approach may be involved in the reaction. Moreover, in the parallel experiments, a KIE value of 1.1 was observed between 1a or [D1]-1a with 2a, which indicates that Co-catalyzed C–H bond cleavage should not be the rate determining step (Scheme 3, reaction 3).

Scheme 3: Control experiments and mechanistic studies.

Scheme 3: Control experiments and mechanistic studies.

On the basis of the above studies and previous literature [30,31,46,47], a plausible reaction mechanism for cobalt-catalyzed alkoxylation was proposed. As shown in Scheme 4, initially, CoIIX2 could be oxidized to CoIIIX2OR in the presence of a silver salt and an alcohol. Based on the experiments and the density functional theory calculations (DFT) [30,31], the C–H activation most possibly proceeded via a single-electron transfer (SET) path compared to a concerted metalation-deprotonation (CMD) path. Followed by an intermolecular SET process, the cation-radical intermediate A was generated, which coordinates with a CoIII species to provide the intermediate B. Subsequently, the transfer of ligand OR from the coordinated CoIII to the naphthalene ring led to the formation of intermediate C. Finally, the alkoxylated product 3aa was released accompanied with the deprotonation and the CoII species was transformed into the CoIII species by re-oxidization.

The current alkoxylation methodology also exhibited potential applications. When treated with NaOH at 80 °C, the picolinic acid directing group could be easily removed, and the corresponding 4 was obtained in 88% yield (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5: Removal of the directing group.

Scheme 5: Removal of the directing group.

Conclusion

In summary, a cobalt-catalyzed C8 alkoxylation of naphthylamine derivatives with both primary and secondary alcohols was developed. This protocol is characterized by mild reaction conditions, broad substrate scope, and good functional group tolerance. Moreover, the excellent compatibility of fluorine-substituted alcohols (for instance, HFIP, trifluoroethanol, and 3-fluoropropanol etc.) shows that this strategy is highly valuable for the syntheses of biologically relevant fluorine-aryl ethers after the removal of the directing group. The above studies of the mechanism indicate that this reaction undergoes a SET process and cobalt salt is the actual catalyst. Overall, this protocol provides a new insight into the cobalt-catalyzed alkoxylation of naphthylamine derivatives. Further exploration of this strategy to aliphatic substrates is currently in progress.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental details and characterization data of new compounds, and X-ray crystal structure details for 3aa. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.7 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: Crystallographic information file for compound 3aa. | ||

| Format: CIF | Size: 282.8 KB | Download |

References

-

Enthaler, S.; Company, A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4912–4924. doi:10.1039/c1cs15085e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Altman, R. A.; Shafir, A.; Choi, A.; Lichtor, P. A.; Buchwald, S. L. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 284–286. doi:10.1021/jo702024p

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hartwig, J. F. Nature 2008, 455, 314–322. doi:10.1038/nature07369

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Monnier, F.; Taillefer, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6954–6971. doi:10.1002/anie.200804497

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bruice, T. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 702–705. doi:10.1021/ja01560a055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Beccalli, E. M.; Broggini, G.; Martinelli, M.; Sottocornola, S. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5318–5365. doi:10.1021/cr068006f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, X.; Hao, X.-S.; Goodhue, C. E.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6790–6791. doi:10.1021/ja061715q

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Colby, D. A.; Bergman, R. G.; Ellman, J. A. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 624–655. doi:10.1021/cr900005n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xiao, B.; Gong, T.-J.; Liu, Z.-J.; Liu, J.-H.; Luo, D.-F.; Xu, J.; Liu, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9250–9253. doi:10.1021/ja203335u

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, Y.; Yoshikai, N. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5504–5507. doi:10.1021/ol202229w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

John, A.; Nicholas, K. M. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 4158–4162. doi:10.1021/jo200409h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Q. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1078–1081. doi:10.1021/ol203442a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, C.; Feng, P.; Jiao, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 15257–15262. doi:10.1021/ja4085463

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, R.; Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Rong, M.; Weng, Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5736–5739. doi:10.1002/anie.201501257

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shan, G.; Yang, X.; Zong, Y.; Rao, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13606–13610. doi:10.1002/anie.201307090

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yan, Y.; Feng, P.; Zheng, Q.-Z.; Liang, Y.-F.; Lu, J.-F.; Cui, Y.; Jiao, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5827–5831. doi:10.1002/anie.201300957

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krylov, I. B.; Vil’, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 92–146. doi:10.3762/bjoc.11.13

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Y.-H.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14654–14655. doi:10.1021/ja907198n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, X.; Liu, Y.-H.; Gu, W.-J.; Li, B.; Chen, F.-J.; Shi, B.-F. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 3904–3907. doi:10.1021/ol5016064

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dick, A. R.; Hull, K. L.; Sanford, M. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2300–2301. doi:10.1021/ja031543m

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheng, X.-F.; Li, Y.; Su, Y.-M.; Yin, F.; Wang, J.-Y.; Sheng, J.; Vora, H. U.; Wang, X.-S.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1236–1239. doi:10.1021/ja311259x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Emmert, M. H.; Cook, A. K.; Xie, Y. J.; Sanford, M. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9409–9412. doi:10.1002/anie.201103327

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hoover, J. M.; Ryland, B. L.; Stahl, S. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2357–2367. doi:10.1021/ja3117203

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kumpulainen, E. T. T.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 10901–10911. doi:10.1002/chem.200901245

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Okada, T.; Asawa, T.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kirihara, M.; Iwai, T.; Kimura, Y. Synlett 2014, 25, 596–598. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1340483

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bhadra, S.; Dzik, W. I.; Gooßen, L. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2959–2962. doi:10.1002/anie.201208755

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Bhadra, S.; Matheis, C.; Katayev, D.; Gooßen, L. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9279–9283. doi:10.1002/anie.201303702

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Desai, L. V.; Malik, H. A.; Sanford, M. S. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 1141–1144. doi:10.1021/ol0530272

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, K.; Ren, B.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 10399–10409. doi:10.1021/jo502005j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zheng, X.-X.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 272–275. doi:10.1002/anie.201409751

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Guo, X.-K.; Zhang, L.-B.; Wei, D.; Niu, J.-L. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 7059–7071. doi:10.1039/C5SC01807B

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Sauermann, N.; Meyer, T. H.; Tian, C.; Ackermann, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18452–18455. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b11025

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wang, G.-W.; Yuan, T.-T. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 476–479. doi:10.1021/jo902139b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Jiang, T.-S.; Wang, G.-W. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9504–9509. doi:10.1021/jo301964m

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, W.; Sun, P. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 8362–8366. doi:10.1021/jo301384r

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kolle, S.; Batra, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 10376–10385. doi:10.1039/C5OB01500F

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Zheng, Y.-W.; Ye, P.; Chen, B.; Meng, Q.-Y.; Feng, K.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.-Z.; Tung, C.-H. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2206–2209. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00463

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yin, Z.; Jiang, X.; Sun, P. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10002–10007. doi:10.1021/jo401623j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Shi, S.; Kuang, C. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6105–6112. doi:10.1021/jo5008306

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, S.; Zhu, W.; Gao, F.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, H. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 126–134. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02257

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yin, X.-S.; Li, Y.-C.; Yuan, J.; Gu, W.-J.; Shi, B.-F. Org. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 119–123. doi:10.1039/C4QO00276H

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lu, W.; Xu, H.; Shen, Z. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 1261–1267. doi:10.1039/C6OB02582J

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yoshikai, N. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2014, 87, 843–857. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20140149

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fallon, B. J.; Derat, E.; Amatore, M.; Aubert, C.; Chemla, F.; Ferreira, F.; Perez-Luna, A.; Petit, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2448–2451. doi:10.1021/ja512728f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moselage, M.; Li, J.; Ackermann, L. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 498–525. doi:10.1021/acscatal.5b02344

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, D.; Zhu, X.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1242–1263. doi:10.1002/cctc.201600040

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Tan, G.; He, S.; Huang, X.; Liao, X.; Cheng, Y.; You, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10414–10418. doi:10.1002/anie.201604580

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Kalsi, D.; Barsu, N.; Sundararaju, B. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 2360–2364. doi:10.1002/chem.201705710

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Du, C.; Li, P.-X.; Zhu, X.; Suo, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13571–13575. doi:10.1002/anie.201607719

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Lin, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 12990–12996. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b07424

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Fang, L.; Song, M.-P.; Niu, J.-L.; Wei, D. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 2668–2677. doi:10.1002/adsc.201800036

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 30. | Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zheng, X.-X.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 272–275. doi:10.1002/anie.201409751 |

| 31. | Guo, X.-K.; Zhang, L.-B.; Wei, D.; Niu, J.-L. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 7059–7071. doi:10.1039/C5SC01807B |

| 30. | Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zheng, X.-X.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 272–275. doi:10.1002/anie.201409751 |

| 32. | Sauermann, N.; Meyer, T. H.; Tian, C.; Ackermann, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18452–18455. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b11025 |

| 1. | Enthaler, S.; Company, A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4912–4924. doi:10.1039/c1cs15085e |

| 8. | Colby, D. A.; Bergman, R. G.; Ellman, J. A. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 624–655. doi:10.1021/cr900005n |

| 9. | Xiao, B.; Gong, T.-J.; Liu, Z.-J.; Liu, J.-H.; Luo, D.-F.; Xu, J.; Liu, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9250–9253. doi:10.1021/ja203335u |

| 10. | Wei, Y.; Yoshikai, N. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5504–5507. doi:10.1021/ol202229w |

| 11. | John, A.; Nicholas, K. M. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 4158–4162. doi:10.1021/jo200409h |

| 12. | Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Q. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1078–1081. doi:10.1021/ol203442a |

| 13. | Zhang, C.; Feng, P.; Jiao, N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 15257–15262. doi:10.1021/ja4085463 |

| 26. | Bhadra, S.; Dzik, W. I.; Gooßen, L. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2959–2962. doi:10.1002/anie.201208755 |

| 27. | Bhadra, S.; Matheis, C.; Katayev, D.; Gooßen, L. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9279–9283. doi:10.1002/anie.201303702 |

| 29. | Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, K.; Ren, B.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 10399–10409. doi:10.1021/jo502005j |

| 41. | Yin, X.-S.; Li, Y.-C.; Yuan, J.; Gu, W.-J.; Shi, B.-F. Org. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 119–123. doi:10.1039/C4QO00276H |

| 42. | Lu, W.; Xu, H.; Shen, Z. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 1261–1267. doi:10.1039/C6OB02582J |

| 6. | Beccalli, E. M.; Broggini, G.; Martinelli, M.; Sottocornola, S. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5318–5365. doi:10.1021/cr068006f |

| 7. | Chen, X.; Hao, X.-S.; Goodhue, C. E.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6790–6791. doi:10.1021/ja061715q |

| 43. | Yoshikai, N. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2014, 87, 843–857. doi:10.1246/bcsj.20140149 |

| 44. | Fallon, B. J.; Derat, E.; Amatore, M.; Aubert, C.; Chemla, F.; Ferreira, F.; Perez-Luna, A.; Petit, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2448–2451. doi:10.1021/ja512728f |

| 45. | Moselage, M.; Li, J.; Ackermann, L. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 498–525. doi:10.1021/acscatal.5b02344 |

| 46. | Wei, D.; Zhu, X.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1242–1263. doi:10.1002/cctc.201600040 |

| 47. | Tan, G.; He, S.; Huang, X.; Liao, X.; Cheng, Y.; You, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10414–10418. doi:10.1002/anie.201604580 |

| 48. | Kalsi, D.; Barsu, N.; Sundararaju, B. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 2360–2364. doi:10.1002/chem.201705710 |

| 49. | Du, C.; Li, P.-X.; Zhu, X.; Suo, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13571–13575. doi:10.1002/anie.201607719 |

| 50. | Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Lin, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 12990–12996. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b07424 |

| 51. | Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Fang, L.; Song, M.-P.; Niu, J.-L.; Wei, D. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 2668–2677. doi:10.1002/adsc.201800036 |

| 31. | Guo, X.-K.; Zhang, L.-B.; Wei, D.; Niu, J.-L. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 7059–7071. doi:10.1039/C5SC01807B |

| 32. | Sauermann, N.; Meyer, T. H.; Tian, C.; Ackermann, L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18452–18455. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b11025 |

| 33. | Wang, G.-W.; Yuan, T.-T. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 476–479. doi:10.1021/jo902139b |

| 34. | Jiang, T.-S.; Wang, G.-W. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9504–9509. doi:10.1021/jo301964m |

| 35. | Li, W.; Sun, P. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 8362–8366. doi:10.1021/jo301384r |

| 36. | Kolle, S.; Batra, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 10376–10385. doi:10.1039/C5OB01500F |

| 37. | Zheng, Y.-W.; Ye, P.; Chen, B.; Meng, Q.-Y.; Feng, K.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.-Z.; Tung, C.-H. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2206–2209. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00463 |

| 38. | Yin, Z.; Jiang, X.; Sun, P. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10002–10007. doi:10.1021/jo401623j |

| 39. | Shi, S.; Kuang, C. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6105–6112. doi:10.1021/jo5008306 |

| 40. | Li, S.; Zhu, W.; Gao, F.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, H. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 126–134. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02257 |

| 41. | Yin, X.-S.; Li, Y.-C.; Yuan, J.; Gu, W.-J.; Shi, B.-F. Org. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 119–123. doi:10.1039/C4QO00276H |

| 42. | Lu, W.; Xu, H.; Shen, Z. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 1261–1267. doi:10.1039/C6OB02582J |

| 2. | Altman, R. A.; Shafir, A.; Choi, A.; Lichtor, P. A.; Buchwald, S. L. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 284–286. doi:10.1021/jo702024p |

| 3. | Hartwig, J. F. Nature 2008, 455, 314–322. doi:10.1038/nature07369 |

| 4. | Monnier, F.; Taillefer, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6954–6971. doi:10.1002/anie.200804497 |

| 28. | Desai, L. V.; Malik, H. A.; Sanford, M. S. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 1141–1144. doi:10.1021/ol0530272 |

| 33. | Wang, G.-W.; Yuan, T.-T. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 476–479. doi:10.1021/jo902139b |

| 34. | Jiang, T.-S.; Wang, G.-W. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9504–9509. doi:10.1021/jo301964m |

| 35. | Li, W.; Sun, P. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 8362–8366. doi:10.1021/jo301384r |

| 36. | Kolle, S.; Batra, S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 10376–10385. doi:10.1039/C5OB01500F |

| 37. | Zheng, Y.-W.; Ye, P.; Chen, B.; Meng, Q.-Y.; Feng, K.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.-Z.; Tung, C.-H. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2206–2209. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00463 |

| 38. | Yin, Z.; Jiang, X.; Sun, P. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10002–10007. doi:10.1021/jo401623j |

| 39. | Shi, S.; Kuang, C. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6105–6112. doi:10.1021/jo5008306 |

| 40. | Li, S.; Zhu, W.; Gao, F.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, H. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 126–134. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02257 |

| 7. | Chen, X.; Hao, X.-S.; Goodhue, C. E.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6790–6791. doi:10.1021/ja061715q |

| 23. | Hoover, J. M.; Ryland, B. L.; Stahl, S. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2357–2367. doi:10.1021/ja3117203 |

| 24. | Kumpulainen, E. T. T.; Koskinen, A. M. P. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009, 15, 10901–10911. doi:10.1002/chem.200901245 |

| 25. | Okada, T.; Asawa, T.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kirihara, M.; Iwai, T.; Kimura, Y. Synlett 2014, 25, 596–598. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1340483 |

| 28. | Desai, L. V.; Malik, H. A.; Sanford, M. S. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 1141–1144. doi:10.1021/ol0530272 |

| 20. | Dick, A. R.; Hull, K. L.; Sanford, M. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2300–2301. doi:10.1021/ja031543m |

| 21. | Cheng, X.-F.; Li, Y.; Su, Y.-M.; Yin, F.; Wang, J.-Y.; Sheng, J.; Vora, H. U.; Wang, X.-S.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1236–1239. doi:10.1021/ja311259x |

| 22. | Emmert, M. H.; Cook, A. K.; Xie, Y. J.; Sanford, M. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9409–9412. doi:10.1002/anie.201103327 |

| 29. | Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, K.; Ren, B.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 10399–10409. doi:10.1021/jo502005j |

| 30. | Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zheng, X.-X.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 272–275. doi:10.1002/anie.201409751 |

| 18. | Zhang, Y.-H.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14654–14655. doi:10.1021/ja907198n |

| 19. | Li, X.; Liu, Y.-H.; Gu, W.-J.; Li, B.; Chen, F.-J.; Shi, B.-F. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 3904–3907. doi:10.1021/ol5016064 |

| 30. | Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zheng, X.-X.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 272–275. doi:10.1002/anie.201409751 |

| 31. | Guo, X.-K.; Zhang, L.-B.; Wei, D.; Niu, J.-L. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 7059–7071. doi:10.1039/C5SC01807B |

| 46. | Wei, D.; Zhu, X.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1242–1263. doi:10.1002/cctc.201600040 |

| 47. | Tan, G.; He, S.; Huang, X.; Liao, X.; Cheng, Y.; You, J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10414–10418. doi:10.1002/anie.201604580 |

| 14. | Huang, R.; Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Rong, M.; Weng, Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5736–5739. doi:10.1002/anie.201501257 |

| 15. | Shan, G.; Yang, X.; Zong, Y.; Rao, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13606–13610. doi:10.1002/anie.201307090 |

| 16. | Yan, Y.; Feng, P.; Zheng, Q.-Z.; Liang, Y.-F.; Lu, J.-F.; Cui, Y.; Jiao, N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5827–5831. doi:10.1002/anie.201300957 |

| 17. | Krylov, I. B.; Vil’, V. A.; Terent’ev, A. O. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 92–146. doi:10.3762/bjoc.11.13 |

| 26. | Bhadra, S.; Dzik, W. I.; Gooßen, L. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2959–2962. doi:10.1002/anie.201208755 |

| 27. | Bhadra, S.; Matheis, C.; Katayev, D.; Gooßen, L. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9279–9283. doi:10.1002/anie.201303702 |

| 30. | Zhang, L.-B.; Hao, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-K.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zheng, X.-X.; Gong, J.-F.; Niu, J.-L.; Song, M.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 272–275. doi:10.1002/anie.201409751 |

| 31. | Guo, X.-K.; Zhang, L.-B.; Wei, D.; Niu, J.-L. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 7059–7071. doi:10.1039/C5SC01807B |

© 2018 Han et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)