Abstract

Sterically shielded nitroxides of the pyrrolidine series have shown the highest resistance to reduction. Here we report the synthesis of new pyrrolidine nitroxides from 5,5-dialkyl-1-pyrroline N-oxides via the introduction of a pent-4-enyl group to the nitrone carbon followed by an intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction and isoxazolidine ring opening. The kinetics of reduction of the new nitroxides with ascorbate were studied and compared to those of previously published (1S,2R,3′S,4′S,5′S,2″R)-dispiro[(2-hydroxymethyl)cyclopentan-1,2′-(3′,4′-di-tert-butoxy)pyrrolidine-5′,1″-(2″-hydroxymethyl)cyclopentane]-1′-oxyl (1).

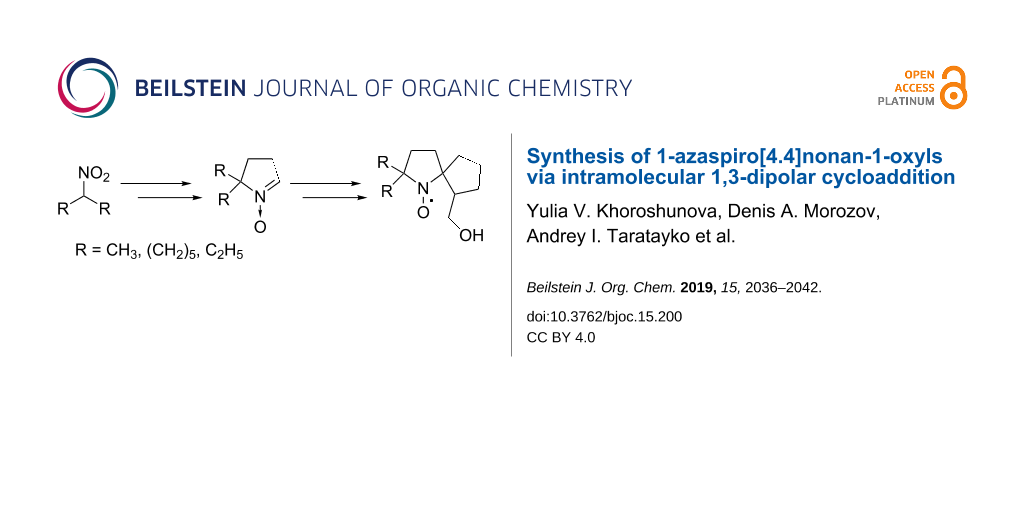

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Sterically shielded nitroxides are currently attracting much attention due to their high resistance to bioreduction [1,2]. It has been demonstrated that 2,2,5,5-tetraethylpyrrolidine nitroxides have the highest stability, sometimes exceeding that of trityl radicals [1]. Introduction of spirocyclic moieties has a smaller effect on the reduction rates of nitroxides than the introduction of linear alkyl substituents does; however, spirocyclic nitroxides may have much longer spin relaxation times at 70–125 K [3] and even at room temperature [4]. The latter effect may be useful for structural studies by means of PELDOR or DQC [5]. We recently reported the synthesis of sterically shielded pyrrolidine nitroxide 1 via a stereospecific consecutive assembly of two spiro-(2-hydroxymethyl)cyclopentane moieties. These procedures included the addition of pent-4-enylmagnesium bromide to the corresponding nitrone, oxidation to alkenylnitrone, intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition, and isoxazolidine ring opening. Nitroxide 1 showed both an unexpectedly low reduction rate [6] and long relaxation times t1 and tm at room temperature [4]. Unexpectedly high resistance of this nitroxide to chemical reduction results from the configuration of the hydroxymethyl groups, which are directed towards the nitroxide group, thereby making it more hindered. It is known that inductive effects of substituents can strongly affect the rate of nitroxide reduction [7,8]; therefore, one could expect that the removal of electron-withdrawing tert-butoxy groups at positions 3 and 4 of the pyrrolidine ring of 1 (Figure 1) should lead to a further decrease in the reduction rate of the nitroxide.

Here we describe the synthesis of C1-symmetric racemic 3,4-unsubstituted pyrrolidine nitroxides with only one spiro(2-hydroxymethyl)cyclopentane moiety. The rates of reduction of the new nitroxides with ascorbate were measured.

Results and Discussion

Aldonitrones 5b,c were prepared similarly to the well-known synthesis of 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-1-oxide (DMPO, 5a) [9,10] from nitrocyclohexane and 3-nitropentane (Scheme 1). In brief, the reaction of nitrocyclohexane and acrolein in a CH3ONa/CH3OH solution afforded the corresponding nitroaldehyde 3b with a 70% yield. Of note, the Michael addition of 3-nitropentane to acrolein was accompanied by remarkable tarring and gave a much lower yield of nitroaldehyde 3c (25%). The reactive aldehyde groups were protected via 1,3-dioxolane assembly, and the resulting compounds were treated with Zn dust and NH4Cl in a water–THF solution to reduce nitro groups. The resulting hydroxylamines were treated with hydrochloric acid to hydrolyse dioxolane moieties, and careful basification resulted in intramolecular cyclisation givnig 5b,c with a yield of 51% and 42%, respectively.

Scheme 1: The synthesis of aldonitrones 5a–c.

Scheme 1: The synthesis of aldonitrones 5a–c.

Nitrones 5a–c readily react with 4-pentenylmagnesium bromide. Quenching of the reaction mixtures with water under aerobic conditions leads to partial oxidation of resultant N-hydroxypyrrolidines 6a–c to corresponding nitrones 7a–c. Therefore, this conversion was finalised via bubbling of air into the solution in the presence of Cu(NH3)42+ (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: The principal synthetic scheme for nitroxides 12a–c.

Scheme 2: The principal synthetic scheme for nitroxides 12a–c.

Samples of resulting 2-(pent-4-enyl)nitrones 7a–c remarkably deteriorate during storage under aerobic conditions with dark tar formation. A possible pathway of decay may include oxidation of the ene-hydroxylamine tautomeric form to vinylnitroxide; similar compounds are prone to various dimerisation reactions (Scheme 3) [11]. It is worth noting that in the mass spectrum of 7c, the [M − 1]+ ion was observed instead of the molecular ion. The easy loss of a hydrogen atom is consistent with the susceptibility of 7c to oxidative decay (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3: A possible pathway of ketonitrone 7c self-transformations.

Scheme 3: A possible pathway of ketonitrone 7c self-transformations.

Intramolecular cycloaddition of similar nitrones is known to lead to hexahydro-1H-cyclopenta[c]isoxazoles [6,12]. Indeed, heating of 7а–с at 145 °C in toluene for 30–60 min in a microwave oven produced 8a–c (racemic mixtures; Scheme 2). The structure assignment was performed on the basis of 1H and 13C NMR spectra and 1H,1H and 13C,1H correlations (see Supporting Information File 1); the spectral data are in agreement with the literature on similar systems [6].

To decrease the tarring, the reaction was carried out in the presence of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl. It should be noted that heating of alkenyl nitrones 7a and 7b gives the corresponding cycloadducts with yields close to quantitative, whereas for nitrone 7c, the complete conversion could not be achieved either at 145 °C or at a higher temperature. According to the 1Н NMR spectra, the 8c/7c ratio never exceeded 3:1. Heating of a pure sample of 8c under similar conditions caused the emergence of signals at 5.70, 4.92, and 4.87 ppm in the 1H NMR spectra. These signals were attributed to the protons of the terminal vinyl group of 7c. 1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition of nitrones to alkenes is known to be reversible [13,14]. We recently reported a similar reversibility of the intramolecular cyclization of sterically hindered pent-4-enylnitrone of the 2H-imidazole series [15].

Treatment with Zn in an AcOH/EtOH/EDTA/Na2 mixture was performed for reductive isoxazolidine ring opening [15,16] producing aminoalcohols 9a–c in 85–95% yields (Scheme 2).

We have previously reported that oxidation of secondary amines with a spiro(2-hydroxymethyl)cyclopentane moiety at the α-carbon with the H2O2/WO42− system is ineffective whereas conversion of these amines to the corresponding nitroxides can be easily performed using m-chloroperbenzoic acid (m-CPBA) [6,15]. Treatment of 9a with m-CPBA in dry chloroform at −10 °C afforded a nitroxide, which was isolated as orange oil with a yield of 73% (Scheme 4). An infrared spectrum of the isolated compound showed a strong absorption band at 1725 cm−1 typical for carbonyl compounds and no absorption in the region 3100–3500 cm−1, suggesting that the hydroxymethyl group was affected in the reaction. The mass spectrum featured the molecular ion [M+] = 196.1335 corresponding to the molecular formula C11H18NO2, which matches element analysis data. These results allowed us to assign the structure 15 to this nitroxide. Indeed, oxidation of amines with peracids is known to proceed via oxoammonium cation formation [17,18], and the latter can oxidize alcohols to carbonyl compounds [19]. The close proximity of the hydroxymethyl group to the oxoammonium one favours the reaction. Treatment of 15 with NaBH4 in EtOH caused quantitative reduction of the aldehyde group to the hydroxymethyl one, thus yielding 12a identical to that prepared by the alternative method (see below).

To prevent oxidative reactions in the side chain, the hydroxymethyl group in 9a–c was protected via acylation. Heating of 9a–c with an excess of acetic anhydride in chloroform quantitatively afforded the corresponding esters 10a–c. The products of acylation of the sterically hindered amino group were not detected in the reaction mixture.

Oxidation of 10а–c with m-CPBA yielded the desired nitroxides 11a–c as orange oils. IR spectra of the new nitroxides contained no absorption bands in the region of 3000–3600 cm−1 and did not have an intense band at 1740 cm−1 characteristic for the ester C=O group. To confirm the structure of the nitroxides, alkoxyamines 16a–c were prepared by Matyjaszhewski's method (Scheme 5) [20].

Scheme 5: The synthesis of alkoxyamines 16a–c.

Scheme 5: The synthesis of alkoxyamines 16a–c.

Oxidation of aminoacetate 10a along with the expected formation of nitroxyl radical 11a, gave another nitroxide, 17, in 22% yield. The IR spectra of 11a and 17 are very similar, showing the bands typical for ester group vibrations and no bands that could be attributed to the vibrations of OH or NH groups. Besides that in the spectrum of compound 17, there are absorption bands near 3054 and 1620 cm−1, which denote the presence of a double C=C bond. To elucidate the structure, nitroxyl radical 17 was converted into alkoxyamine 18 (Scheme 6) using the literature method by Schoening et al. [21], and 1H and 13C NMR spectra, as well as two-dimensional 1H,1H-COSY and 1H,13C-HSQC and HMBC spectra were recorded (see Supporting Information File 1). Signals at 4.14 and 4.45 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum were assigned to the hydrogen atoms of the O–C(10)H2 group. Analysis of the 1H,1H-COSY and 1H,13C-HSQC NMR spectra allowed us to unambiguously assign a signal at 2.26 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum to the methine proton on the C(9) carbon atom (see Supporting Information File 1). This signal in the 1H,1H-COSY spectrum contains two cross-peaks with hydrogens of the O–C(10)H2 group and two additional cross-peaks with signals at 2.11 and 2.36 ppm, which were assigned to the C(8)H2 group. The chemical shifts and character of the splitting for this group of signals correspond to structural fragment O–C(10)H2–C(9)H–C(8)H2. The signals of the C(8)H2 group in the COSY spectrum contain only two additional cross-peaks with the olefin signals at 5.64 and 5.86 ppm. Analysis of the 1H,13C-HSQC spectrum revealed that the latter protons are bound to carbon atoms with chemical shifts 135.3 and 131.1 ppm, respectively, and this finding enabled the assignment of these signals to the 1,2-disubstituted alkene moiety. Thus, the NMR data presented above indicate the presence of an isolated spin system, O–CH2–CH–CH2–CH=CH. A similar analysis of the remaining complex multiplets at 1.56, 1.77, and 1.93 ppm as well as their correlation with the signals of carbon atoms in the 1H,13C-HSQC spectra allowed us to assign these signals to an isolated CH2–CH2 system. All these findings unambiguously support the assignment of structure 18 to the isolated alkoxyamine and structure 17 to the corresponding nitroxide.

Therefore, 17 is formed due to hydrogen abstraction in the spirocyclopentane ring. To the best of our knowledge, similar transformations have never been observed before. Presumably, formation of 17 occurs due to the close proximity of the N+=O group (in the intermediate strained oxoammonium cation) to the hydrogen atom of an adjacent methylene group of the cyclopentane ring (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7: A possible mechanism of nitroxide 17 formation.

Scheme 7: A possible mechanism of nitroxide 17 formation.

The ester groups in 11a–c were easily cleaved in an aqueous–methanol solution of ammonia. Nitroxides 12a–c were isolated as orange compounds moderately soluble in water. Overall yields of these radicals via the acylation–oxidation–deprotection pathway were in the range of 54–75%. Of note, the use of a similar three-step procedure for the synthesis of 1 from 19 increased the yield of this nitroxide from 20% [6] to 60% (Scheme 8).

Scheme 8: Optimisation of the synthesis of nitroxide 1.

Scheme 8: Optimisation of the synthesis of nitroxide 1.

The EPR spectra of nitroxides 12a–c and 1 acquired in a deoxygenated buffer revealed a significant difference in line widths (see Table 1 and Supporting Information File 1, Figures S7–S10), with the broadest lines expectedly being shown by 12b. Introduction of spirocyclohexane moieties to α-carbons of pyrrolidine nitroxides was found to cause strong broadening of lines in the EPR spectra, presumably owing to unresolved hfc on the hydrogens at positions 2 and 6 of the cyclohexane ring [22]. It has been reported that EPR spectra of pyrrolidine or imidazolidine nitroxides with pair(s) of geminal ethyl groups at α-carbon atoms may feature large doublet hyperfine splittings [23-25]. For imidazolidine nitroxides, these splittings were unambiguously attributed to hfc on one of four methylene hydrogens of each pair of ethyls [23]. The difference in apparent hyperfine coupling constant aH on these hydrogens is due to a substituent at position 3 or 4 of the ring. This substituent hinders rotation and affects the population of conformations of neighbouring geminal ethyl groups, thereby preventing averaging. In agreement with this conclusion, there are no large splittings in the EPR spectrum of 12c, and the line width is a bit greater than that in the spectra of similar nonspirocyclic 3,4-unsubstituted 2,2-diethylpyrrolidine nitroxides [26], implying free rotation of ethyl groups. In the EPR spectra in toluene the nitroxides 11a–c show 0.035–0.04 mT lower hfs constants on nitrogen atom compared to nitroxides 12a–c, presumably due to intramolecular hydrogen bond formation. The difference in aN between 11a–c and 12a–c is almost one order of magnitude lower for EPR spectra in water (0.005–0.006 mT), obviously because strong intermolecular hydrogen bonds are formed due to solvation.

Table 1: Parameters of the EPR spectra (hyperfine coupling constants, aN; peak-to-peak linewidths, ΔBp-p; and g-factors), second order rate constants of reduction with ascorbate and partition coefficients octanol-water (Kp) for nitroxides 1 and 12a–c.

| Nitroxide | aN, mT | ΔBp-p, mT | g-factor | k2, M−1s−1 | Kp |

| 1 | 1.481 | 0.29 | 2.00553(±2) | (3.6 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | 600 |

| 12a | 1.595 | 0.21 | 2.00549(±2) | (7.3 ± 0.2) × 10−2 | 12 |

| 12b | 1.586 | 0.34 | 2.00553(±2) | (4.6 ± 0.5) × 10−2 | 130 |

| 12c | 1.570 | 0.24 | 2.00552(±2) | (2.2 ± 0.4) × 10−2 | 80 |

The initial rates of the EPR signal decay were used to obtain the rate constants of the nitroxide reduction by ascorbic acid (see Figure 2 and Supporting Information File 1).

![[1860-5397-15-200-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-15-200-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Kinetics of the reduction of nitroxides 1 and 12a–c (0.3 mM) with ascorbate (50 mM) in 50 mM phosphate-citrate-borate buffer in the presence of glutathione (2 mM), at pH 7.4 and, temperature 293 K. Second-order rate constants, k (M−1s−1), for the initial rates of reduction are presented.

Figure 2: Kinetics of the reduction of nitroxides 1 and 12a–c (0.3 mM) with ascorbate (50 mM) in 50 mM phosph...

The rate constants for all these nitroxides are remarkably higher than this constant for nitroxide 1. Even nitroxide 12c, which is the most stable among the new pyrrolidine nitroxides has a ca. 6-fold higher reduction rate than 1 does, and both are less resistant to reduction than 2,2,5,5-tetraethyl-substituted pyrrolidine nitroxides are (k = 2 × 10−3 to 3.3 × 10−4 ) [1,25]. The rate of reduction of 12a is close to that of 3-carboxy-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidine-1-oxyl [24]. Obviously, a single spiro-(2-hydroxymethyl)cyclopentane moiety cannot provide higher reduction resistance than geminal ethyl groups can. Thus, estimation of the steric effect of neighbouring substituents cannot account for the high reduction resistance of 1. Presumably, the symmetric structure with bulky substituents at positions 3 and 4 is an important factor for nitroxide stability. Due to the steric repulsion of trans-oriented tert-butoxy groups and spiro cyclopentane moieties in the symmetric structure of 1, the (2-hydroxymethyl)cyclopentane groups tightly embrace the nitroxide group making it less accessible for reductants. It is also noteworthy that the symmetric repulsion from both sides of the pyrrolidine ring favours a planar nitroxide group and destabilises the corresponding hydroxylamine with the sp3-hybridised nitrogen. Recently, we observed a similar effect for (3S(R),4S(R))-2,2,5,5-tetraethyl-3,4-bis(hydroxymethyl)pyrrolidine-1-oxyl, which manifested the highest resistance to reduction among known nitroxides [25]. In contrast, structures 12a–c are asymmetric, and corresponding hydroxylamines could be additionally stabilised by hydrogen bonding between the nitrogen atom and the proton of the hydroxymethyl group.

Conclusion

In this study, we again demonstrated feasibility of the general synthetic approach to sterically hindered spirocyclic nitroxides based on an intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction in alkenylnitrones followed by isoxazolidine ring opening. The resulting asymmetric pyrrolidine nitroxides have unexpectedly high rates of reduction with ascorbate. These results lead us to the assumption that symmetric structures with bulky substituents at positions 3 and 4 should be favoured for achieving higher resistance to reduction.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Full experimental details and analytical data (UV, IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and EPR experiments, and microanalysis). | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.3 MB | Download |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grants No. 17-03-01132 [to Yu.V.K. & A.I.T., pyrroline-N-oxides and alkoxyamines] and 18-53-76003 within the framework of the ERA.Net RUS+ project ST2017-382: NanoHyperRadicals [to D.A.M. & I.A.K., nitroxides and writing]), by the Russian Science Foundation (grant No. 19‐13‐00235 to Yu.I.G. kinetics studies, and by the Ministry of Science and Education of the Russian Federation (grant No. 14.W03.31.0034 to P.D.G., EPR measurements). We thank the Multi-Access Chemical Research Center SB RAS for spectral and analytical services.

References

-

Jagtap, A. P.; Krstic, I.; Kunjir, N. C.; Hänsel, R.; Prisner, T. F.; Sigurdsson, S. T. Free Radical Res. 2015, 49, 78–85. doi:10.3109/10715762.2014.979409

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Sasaki, K.; Ito, T.; Fujii, H. G.; Sato, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 1509–1513. doi:10.1248/cpb.c16-00347

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kathirvelu, V.; Smith, C.; Parks, C.; Mannan, M. A.; Miura, Y.; Takeshita, K.; Eaton, S. S.; Eaton, G. R. Chem. Commun. 2009, 454–456. doi:10.1039/b817758a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuzhelev, A. A.; Strizhakov, R. K.; Krumkacheva, O. A.; Polienko, Y. F.; Morozov, D. A.; Shevelev, G. Y.; Pyshnyi, D. V.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Fedin, M. V.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Magn. Reson. 2016, 266, 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2016.02.014

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Meyer, V.; Swanson, M. A.; Clouston, L. J.; Boratyński, P. J.; Stein, R. A.; Mchaourab, H. S.; Rajca, A.; Eaton, S. S.; Eaton, G. R. Biophys. J. 2015, 108, 1213–1219. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2015.01.015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Morozov, D. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Komarov, D. A.; Goti, A.; Bagryanskaya, I. Y.; Kuratieva, N. V.; Grigor’ev, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10688–10698. doi:10.1021/jo3019158

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] -

Morris, S.; Sosnovsky, G.; Hui, B.; Huber, C. O.; Rao, N. U. M.; Swartz, H. M. J. Pharm. Sci. 1991, 80, 149–152. doi:10.1002/jps.2600800212

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kirilyuk, I. A.; Bobko, A. A.; Semenov, S. V.; Komarov, D. A.; Irtegova, I. G.; Grigor’ev, I. A.; Bagryanskaya, E. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9118–9125. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b01494

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Haire, D. L.; Janzen, E. G. Can. J. Chem. 1982, 60, 1514–1522. doi:10.1139/v82-220

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Turner, M. J.; Rosen, G. M. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29, 2439–2444. doi:10.1021/jm00162a004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aurich, H. G.; Hahn, K.; Stork, K. Chem. Ber. 1979, 112, 2776–2785. doi:10.1002/cber.19791120803

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dondas, H. A.; Grigg, R.; Hadjisoteriou, M.; Markandu, J.; Thomas, W. A.; Kennewell, P. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 10087–10096. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(00)01012-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Coşkun, N. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 13873–13882. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(97)00876-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Coşkun, N.; Tirli Tat, F.; Özel Güven, Ö. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 3413–3417. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)00184-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Edeleva, M. V.; Parkhomenko, D. A.; Morozov, D. A.; Dobrynin, S. A.; Trofimov, D. G.; Kanagatov, B.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 929–943. doi:10.1002/pola.27071

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Sár, C. P.; Ősz, E.; Jekő, J.; Hideg, K. Synthesis 2005, 255–259. doi:10.1055/s-2004-834937

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sen, V. D.; Golubev, V. A.; Efremova, N. N. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. (Engl. Transl.) 1982, 31, 53–63. doi:10.1007/bf00954410

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Toshimasa, T.; Eiko, M.; Keisuke, M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1972, 45, 1904–1908. doi:10.1246/bcsj.45.1904

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bobbitt, J. M.; Brückner, C.; Merbouh, N. Org. React. 2009, 74, 103–424. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or074.02

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Matyjaszewski, K.; Woodworth, B. E.; Zhang, X.; Gaynor, S. G.; Metzner, Z. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 5955–5957. doi:10.1021/ma9807264

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dichtl, A.; Seyfried, M.; Schoening, K.-U. Synlett 2008, 1877–1881. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1078526

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kirilyuk, I. A.; Polienko, Y. F.; Krumkacheva, O. A.; Strizhakov, R. K.; Gatilov, Y. V.; Grigor’ev, I. A.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 8016–8027. doi:10.1021/jo301235j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bobko, A. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Gritsan, N. P.; Polovyanenko, D. N.; Grigor’ev, I. A.; Khramtsov, V. V.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2010, 39, 437–451. doi:10.1007/s00723-010-0179-z

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Paletta, J. T.; Pink, M.; Foley, B.; Rajca, S.; Rajca, A. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5322–5325. doi:10.1021/ol302506f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Dobrynin, S. A.; Glazachev, Y. I.; Gatilov, Y. V.; Chernyak, E. I.; Salnikov, G. E.; Kirilyuk, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 5392–5397. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00085

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Lampp, L.; Morgenstern, U.; Merzweiler, K.; Imming, P.; Seidel, R. W. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1182, 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.01.015

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 25. | Dobrynin, S. A.; Glazachev, Y. I.; Gatilov, Y. V.; Chernyak, E. I.; Salnikov, G. E.; Kirilyuk, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 5392–5397. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00085 |

| 1. | Jagtap, A. P.; Krstic, I.; Kunjir, N. C.; Hänsel, R.; Prisner, T. F.; Sigurdsson, S. T. Free Radical Res. 2015, 49, 78–85. doi:10.3109/10715762.2014.979409 |

| 2. | Sasaki, K.; Ito, T.; Fujii, H. G.; Sato, S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 1509–1513. doi:10.1248/cpb.c16-00347 |

| 5. | Meyer, V.; Swanson, M. A.; Clouston, L. J.; Boratyński, P. J.; Stein, R. A.; Mchaourab, H. S.; Rajca, A.; Eaton, S. S.; Eaton, G. R. Biophys. J. 2015, 108, 1213–1219. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2015.01.015 |

| 15. | Edeleva, M. V.; Parkhomenko, D. A.; Morozov, D. A.; Dobrynin, S. A.; Trofimov, D. G.; Kanagatov, B.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 929–943. doi:10.1002/pola.27071 |

| 16. | Sár, C. P.; Ősz, E.; Jekő, J.; Hideg, K. Synthesis 2005, 255–259. doi:10.1055/s-2004-834937 |

| 4. | Kuzhelev, A. A.; Strizhakov, R. K.; Krumkacheva, O. A.; Polienko, Y. F.; Morozov, D. A.; Shevelev, G. Y.; Pyshnyi, D. V.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Fedin, M. V.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Magn. Reson. 2016, 266, 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2016.02.014 |

| 6. | Morozov, D. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Komarov, D. A.; Goti, A.; Bagryanskaya, I. Y.; Kuratieva, N. V.; Grigor’ev, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10688–10698. doi:10.1021/jo3019158 |

| 15. | Edeleva, M. V.; Parkhomenko, D. A.; Morozov, D. A.; Dobrynin, S. A.; Trofimov, D. G.; Kanagatov, B.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 929–943. doi:10.1002/pola.27071 |

| 3. | Kathirvelu, V.; Smith, C.; Parks, C.; Mannan, M. A.; Miura, Y.; Takeshita, K.; Eaton, S. S.; Eaton, G. R. Chem. Commun. 2009, 454–456. doi:10.1039/b817758a |

| 13. | Coşkun, N. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 13873–13882. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(97)00876-4 |

| 14. | Coşkun, N.; Tirli Tat, F.; Özel Güven, Ö. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 3413–3417. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)00184-3 |

| 1. | Jagtap, A. P.; Krstic, I.; Kunjir, N. C.; Hänsel, R.; Prisner, T. F.; Sigurdsson, S. T. Free Radical Res. 2015, 49, 78–85. doi:10.3109/10715762.2014.979409 |

| 15. | Edeleva, M. V.; Parkhomenko, D. A.; Morozov, D. A.; Dobrynin, S. A.; Trofimov, D. G.; Kanagatov, B.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 929–943. doi:10.1002/pola.27071 |

| 9. | Haire, D. L.; Janzen, E. G. Can. J. Chem. 1982, 60, 1514–1522. doi:10.1139/v82-220 |

| 10. | Turner, M. J.; Rosen, G. M. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29, 2439–2444. doi:10.1021/jm00162a004 |

| 6. | Morozov, D. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Komarov, D. A.; Goti, A.; Bagryanskaya, I. Y.; Kuratieva, N. V.; Grigor’ev, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10688–10698. doi:10.1021/jo3019158 |

| 12. | Dondas, H. A.; Grigg, R.; Hadjisoteriou, M.; Markandu, J.; Thomas, W. A.; Kennewell, P. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 10087–10096. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(00)01012-7 |

| 7. | Morris, S.; Sosnovsky, G.; Hui, B.; Huber, C. O.; Rao, N. U. M.; Swartz, H. M. J. Pharm. Sci. 1991, 80, 149–152. doi:10.1002/jps.2600800212 |

| 8. | Kirilyuk, I. A.; Bobko, A. A.; Semenov, S. V.; Komarov, D. A.; Irtegova, I. G.; Grigor’ev, I. A.; Bagryanskaya, E. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9118–9125. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b01494 |

| 6. | Morozov, D. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Komarov, D. A.; Goti, A.; Bagryanskaya, I. Y.; Kuratieva, N. V.; Grigor’ev, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10688–10698. doi:10.1021/jo3019158 |

| 4. | Kuzhelev, A. A.; Strizhakov, R. K.; Krumkacheva, O. A.; Polienko, Y. F.; Morozov, D. A.; Shevelev, G. Y.; Pyshnyi, D. V.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Fedin, M. V.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Magn. Reson. 2016, 266, 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2016.02.014 |

| 6. | Morozov, D. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Komarov, D. A.; Goti, A.; Bagryanskaya, I. Y.; Kuratieva, N. V.; Grigor’ev, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10688–10698. doi:10.1021/jo3019158 |

| 11. | Aurich, H. G.; Hahn, K.; Stork, K. Chem. Ber. 1979, 112, 2776–2785. doi:10.1002/cber.19791120803 |

| 20. | Matyjaszewski, K.; Woodworth, B. E.; Zhang, X.; Gaynor, S. G.; Metzner, Z. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 5955–5957. doi:10.1021/ma9807264 |

| 17. | Sen, V. D.; Golubev, V. A.; Efremova, N. N. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. (Engl. Transl.) 1982, 31, 53–63. doi:10.1007/bf00954410 |

| 18. | Toshimasa, T.; Eiko, M.; Keisuke, M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1972, 45, 1904–1908. doi:10.1246/bcsj.45.1904 |

| 19. | Bobbitt, J. M.; Brückner, C.; Merbouh, N. Org. React. 2009, 74, 103–424. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or074.02 |

| 1. | Jagtap, A. P.; Krstic, I.; Kunjir, N. C.; Hänsel, R.; Prisner, T. F.; Sigurdsson, S. T. Free Radical Res. 2015, 49, 78–85. doi:10.3109/10715762.2014.979409 |

| 25. | Dobrynin, S. A.; Glazachev, Y. I.; Gatilov, Y. V.; Chernyak, E. I.; Salnikov, G. E.; Kirilyuk, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 5392–5397. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00085 |

| 24. | Paletta, J. T.; Pink, M.; Foley, B.; Rajca, S.; Rajca, A. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5322–5325. doi:10.1021/ol302506f |

| 23. | Bobko, A. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Gritsan, N. P.; Polovyanenko, D. N.; Grigor’ev, I. A.; Khramtsov, V. V.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2010, 39, 437–451. doi:10.1007/s00723-010-0179-z |

| 26. | Lampp, L.; Morgenstern, U.; Merzweiler, K.; Imming, P.; Seidel, R. W. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1182, 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.01.015 |

| 22. | Kirilyuk, I. A.; Polienko, Y. F.; Krumkacheva, O. A.; Strizhakov, R. K.; Gatilov, Y. V.; Grigor’ev, I. A.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 8016–8027. doi:10.1021/jo301235j |

| 23. | Bobko, A. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Gritsan, N. P.; Polovyanenko, D. N.; Grigor’ev, I. A.; Khramtsov, V. V.; Bagryanskaya, E. G. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2010, 39, 437–451. doi:10.1007/s00723-010-0179-z |

| 24. | Paletta, J. T.; Pink, M.; Foley, B.; Rajca, S.; Rajca, A. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5322–5325. doi:10.1021/ol302506f |

| 25. | Dobrynin, S. A.; Glazachev, Y. I.; Gatilov, Y. V.; Chernyak, E. I.; Salnikov, G. E.; Kirilyuk, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 5392–5397. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00085 |

| 21. | Dichtl, A.; Seyfried, M.; Schoening, K.-U. Synlett 2008, 1877–1881. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1078526 |

| 6. | Morozov, D. A.; Kirilyuk, I. A.; Komarov, D. A.; Goti, A.; Bagryanskaya, I. Y.; Kuratieva, N. V.; Grigor’ev, I. A. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10688–10698. doi:10.1021/jo3019158 |

© 2019 Khoroshunova et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the authors and source are credited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)