Abstract

We describe the synthesis of so far synthetically not accessible 3,6-substituted-4,6-dihydro-3H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazines as nitrogen-rich heterocycles. The target compounds were obtained in five steps, including an amidation and a cyclative cleavage reaction as key reaction steps. The introduction of two side chains allowed a variation of the pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazine core with commercially available building blocks, enabling the extension of the protocol to gain other derivatives straightforwardly. Attempts to synthesize 3,7-substituted-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazines, the regioisomers of the successfully gained 3,6-substituted 4,6-dihydro-3H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazines, were not successful under similar conditions due to the higher stability of the triazene functionality in the regioisomeric precursors and thus, the failure of the removal of the protective group.

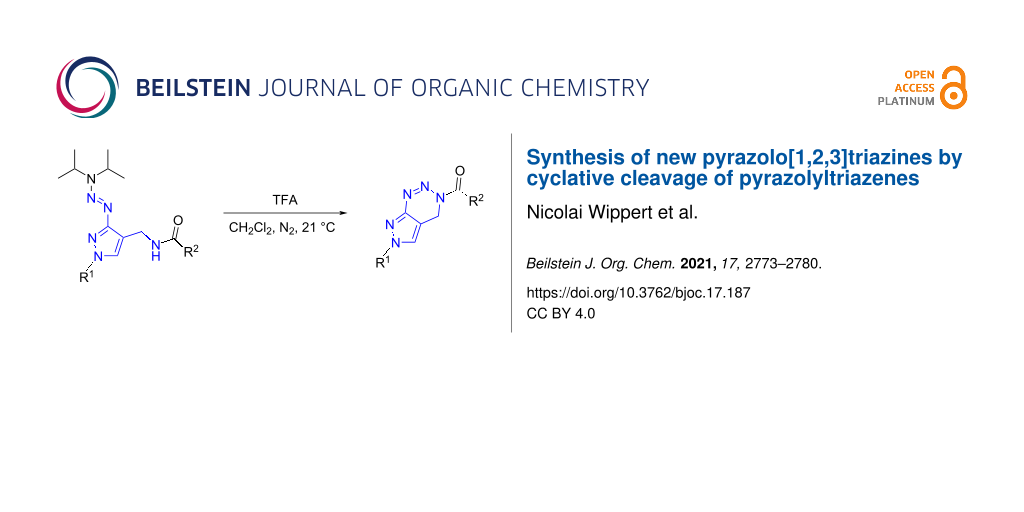

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The structural motif of pyrazolotriazines, particularly the pyrazolotriazinones, has drawn attention regarding a possible application as therapeutic agents due to manifold biological activities. Amongst other known constitutional isomers such as pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazines [1-3] and pyrazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazines [4-6], pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazines [7-34] and their derivatives are literature known and subject of different biological studies. Pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazines and their derivatives, for example, were reported to function as anticancer compounds [28,29,32], herbicides [19-21], antimicrobials [18], and pest control agents [35].

Several possibilities have been reported to gain the scaffold of pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazines synthetically and successful syntheses of different manifold isomers. 3,6-Dihydro-4H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazin-4-ones 2, as one example of the diverse compound class, can be gained via diazotization of 3-amino-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxamides 1a or 3-amino-1H-pyrazole-4-carbonitriles 1b and subsequent cyclization of the intermediate diazo compounds under acidic conditions [22] (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Synthesis of 3,6-dihydro-4H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazin-4-ones 2a,b by diazotization of 3-amino-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxamides 1a or 3-amino-1H-pyrazole-4-carbonitriles 1b [22].

Scheme 1: Synthesis of 3,6-dihydro-4H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazin-4-ones 2a,b by diazotization of 3-amino-1H...

The structurally related 3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazin-4-ones 3 (Figure 1) which are substituted in position N-7 can be obtained in the same manner as described in Scheme 1, if the substitution position R1 in the starting 3-amino-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxamides 1a or 3-amino-1H-pyrazole-4-carbonitriles 1b is altered [26]. Furthermore, several 2,7-dihydro-3H-imidazo[1,2-c]pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,3]triazines 4 were described. However, while 3,6-substituted-3,6-dihydro-4H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazin-4-ones 2 and 3,7-substituted-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazin-4-ones 3 are reported in several references dealing with their synthesis, modification, and application [36], their non-oxidized derivatives 5 and 6 are yet, to the best of our knowledge, unknown in the literature.

Figure 1: Structural differences of several known (2–4) and so far unknown (5 and 6) pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazine derivatives.

Figure 1: Structural differences of several known (2–4) and so far unknown (5 and 6) pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H...

In the past, it was shown that ortho-methylamide-substituted aryltriazenes 7 could be efficiently converted into 3,4-dihydrobenzo[d][1,2,3]triazine derivatives 8 [37] (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of 3,4-dihydrobenzo[d][1,2,3]triazine derivatives 8 from triazene-containing precursors 7 [37].

Scheme 2: Synthesis of 3,4-dihydrobenzo[d][1,2,3]triazine derivatives 8 from triazene-containing precursors 7 ...

In this context, triazenes have shown beneficial properties as they can be used as protected diazonium species which can be handled and converted in various transformations without decomposition [37-39]. In the herein presented study, we apply the cyclative cleavage reaction to pyrazolyltriazenes instead of aryltriazenes, which results in the synthesis of diverse pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazine derivatives 5.

Results and Discussion

According to the literature-known synthetic access to benzotriazines 8, we designed a retrosynthetic route consisting of five steps to gain 4,6-dihydropyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazines 5 and 4,7-dihydropyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazines 6 starting from pyrazolyltriazenes 15 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3: Planned retrosynthesis to obtain 4,6-dihydropyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazines 5 and 4,7-dihydropyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazines 6 from pyrazolylamines 16. DIPA = diisopropylamine.

Scheme 3: Planned retrosynthesis to obtain 4,6-dihydropyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazines 5 and 4,7-dihydropy...

The sequence contains two key steps that have a major influence on the outcome of the reaction: (1) the addition of side chains R1 to the core pyrazole ring system, which can occur in position N-6 or N-7, and (2) the cyclative cleavage of the triazene group of compounds 9 and 10 which should lead to the target compounds 5 and 6. To carry out the designed synthetic route, 3-(3,3-diisopropyltriaz-1-en-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carbonitrile (15) was synthesized in a first step using the commercially available 3-amino-1H-pyrazole-4-carbonitrile (16). Thus, the aminopyrazole was diazotized in aqueous media using hydrochloric acid and sodium nitrite. Diisopropylamine and an aqueous solution of potassium carbonate were added to the in-situ generated diazonium salt according to literature-known protocols [40]. The resulting 3-(3,3-diisopropyltriaz-1-en-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carbonitrile (15) was used as starting material for the attempts to add different side chains to the pyrazole moiety.

The addition of several aliphatic bromides or iodides 14 in combination with potassium or cesium carbonate in DMSO gave a mixture of the regioisomeric compounds 12 and 13 due to the addition of the alkyl substituents to one of both pyrazole-nitrogen atoms. As shown in Table 1, the alkylation protocol did not give a selective conversion in favor of one of the generated isomers. The protocol was not changed or adapted to gain a higher selectivity of one of the isomers, as both regioisomers were used in the subsequent syntheses.

Table 1: Synthesis of N-substituted pyrazoles 12 and 13.

|

|

|||||

| entrya | 14 (equiv) | R1 | X | 12 (yield) | 13 (yield) |

| 1 | 14a (2.0) | Bn | Br | 12a (54%) | 13a (36%) |

| 2 | 14b (1.5) | tolyl-CH2 | Br | 12b (59%) | 13b (40%) |

| 3 | 14c (2.0) | 3,5-difluorobenzyl | Br | 12c (48%) | 13c (42%) |

| 4b | 14d (1.2) | ethyl | I | 12d (34%) | 13d (57%) |

| 5b | 14e (1.2) | cyclopentyl | Br | 12e (39%) | 13e (52%) |

| 6 | 14f (1.2) | isobutyl | Br | 12f (28%) | 13f (47%) |

| 7c | 14g (1.1) | EtO2COCH2 | Br | 12g (54%) | 13g (15%) |

| 8b | 14h (2.0) | 4-bromobenzyl | Br | 12h (51%) | 13h (42%) |

aTypical conditions for the conversion are: 15, Cs2CO3 or K2CO3 (1.2 equiv), 14 (1.1–2.0 equiv), DMSO, room temperature; the products 12 and 13 were separated by column chromatography. bThe conditions were varied in temperature (reaction temperature was 80 °C for entries 4 and 5 and 40 °C for entry 8. c0.95 equiv of K2CO3 were used.

For the derivatives 12h and 13c, we were able to exemplarily determine the molecular structure by X-ray crystallography, proving the regioisomer obtained in the alkylation reaction (Figure 2).

![[1860-5397-17-187-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-17-187-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: Molecular structures of compounds 12h (A) and 13c (B) representing both possible regioisomers of the alkylation reaction (displacement parameters are drawn at the 50% probability level). The X-ray data corroborate the obtained NMR data.

Figure 2: Molecular structures of compounds 12h (A) and 13c (B) representing both possible regioisomers of th...

While isomer 12 was used for the synthesis of pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazine derivatives of general structure 5, the isomer 13 was intended to deliver pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazine derivative of general structure 6. The synthetic sequence to compounds 5 is described in detail in the following sections. The synthesis of the precursors to compound 6 derived from 13 is shifted to Supporting Information File 1 as the cyclative cleavage to the final product 6 failed in the last step of the synthesis.

The conversion of 12 to the reduced aminomethyl compounds 17 was challenging. While the reduction with LiAlH4 in THF gave good results (shown via TLC and LC–MS analysis), the isolated products were not stable and degraded quickly, making full characterization impossible. Therefore, the crude aminomethyl compounds 17a–g were directly converted to the corresponding amides 9a–i using different anhydrides or acid chlorides 11a–c. The resulting amides were stable and gained mediocre to good yields except for amides 9a and 9d (Table 2). The yield of 9d was found to be very low due to a reductive replacement of the fluoro atoms of the benzyl ring during the reduction of the nitrile with LiAlH4. Only a small amount (5% yield) of the desired compound was isolated. Also, a reductive replacement was observed during the conversion of 12h, yielding the intermediate 17a with R1 = Bn instead of R1 = bromobenzyl. Depending on the nature of the side chain R1 in compounds 12a–g, the reduction to compounds 17a–g leads to a change of R1 to a different side chain R1' which can be used for further transformation to R1'' by conversion with electrophiles. This was shown with compound 12g (R1 = -CH2CO2Et), being reduced to compound 17g (R1' = -(CH2)2OH) and acylated to 9i with R1'' = -(CH2)2OCOMe.

Table 2: Synthesis of amides 9a–i via reduction of nitriles 12a–g to pyrazolo-ortho-methylamines and subsequent conversion with aliphatic anhydrides or chlorides 11a–c.

|

|

||||||||

| entrya | 12 | R1 (12) | 17 | 11 | 9 | R1'' (9) | R2 | yield 9 (%) |

| 1 | 12a | Bn | 17a | 11a | 9a | Bn | Me | 23 |

| 2b | 12a | Bn | 17a | 11b | 9b | Bn | Ph | 41 |

| 3 | 12b | 4-methylbenzyl | 17b | 11c | 9c | p-tolyl-CH2 | iBu | 61 |

| 4b | 12c | 3,5-difluorobenzyl | 17c | 11a | 9d | 3,5-difluorobenzyl | Me | 5 |

| 5 | 12d | ethyl | 17d | 11a | 9e | ethyl | Me | 59 |

| 6 | 12e | cyclopentyl | 17e | 11a | 9f | cyclopentyl | Me | 74 |

| 7 | 12e | cyclopentyl | 17e | 11b | 9g | cyclopentyl | Ph | 63 |

| 8 | 12f | isobutyl | 17f | 11a | 9h | isobutyl | Me | 52 |

| 9 | 12g | EtCO2CH2 | 17g | 11a | 9i | MeCO2(CH2)2 | Me | 72 |

aThe reaction consists of two steps. The intermediate compound 17 was isolated but not purified and used as obtained. Conditions: first step: 12, LiAlH4 (3.0 equiv), THF, 0 °C to 21 °C, then 50 °C. Second step: 11 (X = OCOR2) (1.5 equiv), THF, 0 °C to 21 °C. bIn a modified protocol, acid chlorides were used instead of anhydrides to introduce R2. The second step was altered as follows: 11 (X = Cl) (1.5 equiv), THF, NEt3 (3.0 equiv), 0 °C to 21 °C.

The last step in the synthesis of the target compounds 5a–i included the cleavage of the triazene unit of the amides 9 with subsequent cyclization to the final pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazine compounds 5 (Scheme 4). The successful cyclizations gave the desired pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]triazines 5 in moderate to good yields. Not all cyclization products were air-stable. While compounds 5a–d with a benzylic side chain in R1'' were stable, a full characterization was possible, especially pyrazolotriazines with an aliphatic substituent on the pyrazole-nitrogen (5e–i) degraded rapidly in contact with air/moisture.

Scheme 4: Cleavage of the triazene protective group and cyclization of the resulting diazonium intermediate yielding pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazine derivatives 5a–i.

Scheme 4: Cleavage of the triazene protective group and cyclization of the resulting diazonium intermediate y...

The conversion of the regioisomeric compounds 10 to 6 failed under the conditions described in Scheme 4. The triazene protective group could not be cleaved even under harsh conditions (temperatures up to 100 °C in dichloroethane and use of H2SO4 as acid), and the starting material was recovered in all of the reactions.

Selected final compounds 5 and intermediates 9, 12, 13, and 17 obtained in this work were tested for their cytotoxicity. We conducted standardized MTT assays [41] to evaluate if the newly accessible compounds of type 5 and their precursors could become interesting target molecules for biological investigations or if the compounds show high toxicity, which might prevent their use. We monitored cytotoxicity at six different concentrations ranging from 0.5 µM to 50 µM (for detailed results, see Supporting Information File 1). It was found that the exemplarily chosen compounds of type 5, namely 5a, 5d–f, and 5h, did not reduce the viability of the human epithelial cervix carcinoma (HeLa) cells at every concentration tested. The derivatives of the target compounds of class 5 were chosen as they were available in sufficient amounts and showed no decomposition during storage and dilution in DMSO. Also, most of the intermediates showed no reduction of cell viability; however, compounds 9b, 12b,c, 13a,b, and 13f–h showed some cytotoxic effects at high concentrations.

Interestingly, no common structural motif promoted an increase in the in vitro cytotoxicity. However, by comparing the IC50 values of the compound classes 12 and 13, regioisomerism seems to play a decisive role: while compounds 12a and 12d–h had no influence on the viability of HeLa cells, their regioisomers 13a and 13d–h decreased the viability at high micromolar concentrations. A slightly increased cytotoxicity of some derivatives of compound class 12 compared to 13 was observed for 12b and 12c. The amides 9 had no influence on the viability except for derivate 9b, characterized by two aromatic moieties at both variable positions R1 and R2. In Table S3 (Supporting Information File 1), the results for compounds 5, 9, 12, and 13 are summarized allowing the direct comparison of the toxicity of the four compound classes with respect to 5 different residues R1. The full data of the toxicity studies for all obtained compounds are given in Supporting Information File 1, Tables S1–S3. Comparing the 20 derivatives depicted in Figure 3 reveals that compounds of the classes 5, 9, and 12 are in general less toxic than the respective compounds of class 13, at least with respect to the derivatives that were obtained in this study.

Figure 3: Graphical overview about selected pyrazolo[1,2,3]triazines 5 and intermediates 9, 12, and 13 and their calculated IC50 values after treatment of HeLa cells with different concentrations of the respective compounds.

Figure 3: Graphical overview about selected pyrazolo[1,2,3]triazines 5 and intermediates 9, 12, and 13 and th...

As the IC50 value of every compound tested lies above the concentration range that is interesting for biological applications, we consider molecules of type 5 as feasible for further biological screenings. We will continue our studies to search for potential targets for the versatile pyrazolo[1,2,3]triazine library presented herein.

Conclusion

In analogy to literature-known acid-induced conversions of triazene-benzyl acetamides to 3,4-dihydrobenzo[d][1,2,3]triazines, so far not described pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazines 5 were successfully synthesized. Altogether nine derivatives 5a–i were synthesized in five steps starting from the commercially available 3-(3,3-diisopropyltriaz-1-en-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carbonitrile. The herein given examples were generated by introducing two side-chains, one on the pyrazole core and the other as a side chain added to a methylamine intermediate in step 2 and step 4 of the reaction sequence. Depending on the introduced side chain, further modifications were obtained (shown for compound 9g). The triazene protective group tolerates the reaction conditions used for the described processes and is probably compatible with many others described in the literature. However, limitations are given to acidic reaction media, which tend to cleave the protective group. So far, the attempts to synthesize compounds of general structure 6, a regioisomer of the successfully gained pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3]-3H-triazines 5, failed under similar procedures.

Abbreviations

TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; THF, tetrahydrofuran, TLC, thin-layer chromatography, LC–MS, liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information contains detailed descriptions of the reactions and protocols as well as the characterization of all target compounds.

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental section and characterization data, biological assay details, and data availability in chemotion repository. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.8 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: Copies of spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 10.7 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 3: Direkt links to datasets and reference numbers of target compounds in Molecule Archive. | ||

| Format: XLSX | Size: 12.5 KB | Download |

Funding

This work was supported by the Helmholtz program Biointerfaces in Technology and Medicine (BIFTM) and the program Information. We acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for the DFG-core facility Molecule Archive, to which all target compounds were registered for further re-use (DFG project number: 284178167).

References

-

Elagamey, A. G. A.; El-Taweel, F. M. A.-A. J. Prakt. Chem. 1991, 333, 333–338. doi:10.1002/prac.19913330220

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kelly, T. R.; Elliott, E. L.; Lebedev, R.; Pagalday, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5646–5647. doi:10.1021/ja060937l

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mojzych, M.; Bielawska, A.; Bielawski, K.; Ceruso, M.; Supuran, C. T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 2643–2647. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2014.03.029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

He, L.; Gilligan, P. J.; Zaczek, R.; Fitzgerald, L. W.; McElroy, J.; Shen, H.-S. L.; Saye, J. A.; Kalin, N. H.; Shelton, S.; Christ, D.; Trainor, G.; Hartig, P. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 449–456. doi:10.1021/jm9904351

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nie, Z.; Perretta, C.; Erickson, P.; Margosiak, S.; Almassy, R.; Lu, J.; Averill, A.; Yager, K. M.; Chu, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 4191–4195. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.05.041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nie, Z.; Perretta, C.; Erickson, P.; Margosiak, S.; Lu, J.; Averill, A.; Almassy, R.; Chu, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 619–623. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.074

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schmidt, P.; Eichenberger, K.; Wilhelm, M. Angew. Chem. 1961, 73, 15–22. doi:10.1002/ange.19610730105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheng, C. C.; Robins, R. K.; Cheng, K. C.; Lin, D. C. J. Pharm. Sci. 1968, 57, 1044–1045. doi:10.1002/jps.2600570634

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cheng, C. C.; Elslager, E. F.; Werbel, L. M.; Leopold, W. R., III. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29, 1544–1547. doi:10.1021/jm00158a041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mitschker, A.; Wedemeyer, K. Synthesis 1988, 517–520. doi:10.1055/s-1988-27622

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ried, W.; Aboul-Fetouh, S. Chem.-Ztg. 1989, 113, 181–183.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Srivastava, R.; Mishra, A.; Pratap, R.; Bhakuni, D. S.; Srimal, R. C. Thromb. Res. 1989, 54, 741–749. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(89)90138-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Maquestiau, A.; Banneux, F.; Vanden Eynde, J. J. Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg. 1991, 100, 401–406. doi:10.1002/bscb.19911000507

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kelley, J. L.; Wilson, D. C.; Styles, V. L.; Soroko, F. E.; Cooper, B. R. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1995, 32, 1417–1421. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570320502

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mekheimer, R. A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1999, 2183–2188. doi:10.1039/a901521c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mekheimer, R. A. Synth. Commun. 2001, 31, 1971–1982. doi:10.1081/scc-100104413

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Döpp, H.; Döpp, D. Sci. Synth. 2004, 17, 223–355. doi:10.1055/sos-sd-017-00001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bondock, S.; Rabie, R.; Etman, H. A.; Fadda, A. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 2122–2129. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.12.009

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, H.-b.; Zhu, Y.-q.; Song, X.-w.; Hu, F.-z.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.-h.; Niu, Z.-x.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.-h.; Song, H.-b.; Zou, X.-m.; Yang, H.-z. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9535–9542. doi:10.1021/jf801774k

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lei, B.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Du, J.; Liu, H.; Yao, X. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 9593–9598. doi:10.1021/jf902010g

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Roy, K.; Paul, S. J. Mol. Model. 2010, 16, 137–153. doi:10.1007/s00894-009-0528-8

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Colomer, J. P.; Moyano, E. L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1561–1565. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.01.040

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Mironovich, L. M.; Shcherbinin, D. V. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 50, 1860–1862. doi:10.1134/s1070428014120306

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bondock, S.; Tarhoni, A. E.-G.; Fadda, A. A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2015, 52, 346–351. doi:10.1002/jhet.2041

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mironovich, L. M.; Shcherbinin, D. V. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 52, 294–297. doi:10.1134/s1070428016020238

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dawood, K. M.; Sayed, S. M.; Raslan, M. A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 2405–2416. doi:10.1002/jhet.2836

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Fadda, A. A.; Rabie, R.; Etman, H. A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 1015–1023. doi:10.1002/jhet.2669

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hassan, A. S.; Moustafa, G. O.; Awad, H. M. Synth. Commun. 2017, 47, 1963–1972. doi:10.1080/00397911.2017.1358368

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nasr, T.; Bondock, S.; Youns, M.; Fayad, W.; Zaghary, W. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 141, 603–614. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.10.016

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Hassan, A. S.; Moustafa, G. O.; Askar, A. A.; Naglah, A. M.; Al-Omar, M. A. Synth. Commun. 2018, 48, 2761–2772. doi:10.1080/00397911.2018.1524492

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sadchikova, E. V.; Alexeeva, D. L.; Nenajdenko, V. G. Mendeleev Commun. 2019, 29, 653–654. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2019.11.016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bondock, S.; Alqahtani, S.; Fouda, A. M. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2021, 58, 56–73. doi:10.1002/jhet.4148

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Seela, F.; Lindner, M.; Glaçon, V.; Lin, W. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 4695–4700. doi:10.1021/jo040150i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harb, A.-F. A.; Abbas, H. H.; Mostafa, F. H. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2005, 2, 115–123. doi:10.1007/bf03247202

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bretschneider, T.; Cerezo-Galvez, S.; Grondal, C.; Fischer, R.; Fuesslein, M.; Reinisch, P.; Gueclue, M.; Ilg, K.; Loesel, P.; Malsam, O. Heterocyclic compounds as pest control agents. WO Pat. Appl. WO 2015/135843 A1, Sept 17, 2015.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khutova, B. M.; Klyuchko, S. V.; Gurenko, A. O.; Vasilenko, A. N.; Balya, A. G.; Rusanov, E. B.; Brovarets, V. S. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2012, 48, 1251–1262. doi:10.1007/s10593-012-1128-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reingruber, R.; Vanderheiden, S.; Muller, T.; Nieger, M.; Es-Sayed, M.; Bräse, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 3439–3442. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.184

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Bräse, S.; Enders, D.; Köbberling, J.; Avemaria, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 3413–3415. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19981231)37:24<3413::aid-anie3413>3.0.co;2-k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nicolaou, K. C.; Li, H.; Boddy, C. N. C.; Ramanjulu, J. M.; Yue, T.-Y.; Natarajan, S.; Chu, X.-J.; Bräse, S.; Rübsam, F. Chem. – Eur. J. 1999, 5, 2584–2601. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(19990903)5:9<2584::aid-chem2584>3.0.co;2-b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Larsen, J. S.; Zahran, M. A.; Pedersen, E. B.; Nielsen, C. Monatsh. Chem. 1999, 130, 1167–1173. doi:10.1007/pl00010295

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mosmann, T. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Elagamey, A. G. A.; El-Taweel, F. M. A.-A. J. Prakt. Chem. 1991, 333, 333–338. doi:10.1002/prac.19913330220 |

| 2. | Kelly, T. R.; Elliott, E. L.; Lebedev, R.; Pagalday, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5646–5647. doi:10.1021/ja060937l |

| 3. | Mojzych, M.; Bielawska, A.; Bielawski, K.; Ceruso, M.; Supuran, C. T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 2643–2647. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2014.03.029 |

| 19. | Li, H.-b.; Zhu, Y.-q.; Song, X.-w.; Hu, F.-z.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.-h.; Niu, Z.-x.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.-h.; Song, H.-b.; Zou, X.-m.; Yang, H.-z. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9535–9542. doi:10.1021/jf801774k |

| 20. | Lei, B.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Du, J.; Liu, H.; Yao, X. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 9593–9598. doi:10.1021/jf902010g |

| 21. | Roy, K.; Paul, S. J. Mol. Model. 2010, 16, 137–153. doi:10.1007/s00894-009-0528-8 |

| 40. | Larsen, J. S.; Zahran, M. A.; Pedersen, E. B.; Nielsen, C. Monatsh. Chem. 1999, 130, 1167–1173. doi:10.1007/pl00010295 |

| 28. | Hassan, A. S.; Moustafa, G. O.; Awad, H. M. Synth. Commun. 2017, 47, 1963–1972. doi:10.1080/00397911.2017.1358368 |

| 29. | Nasr, T.; Bondock, S.; Youns, M.; Fayad, W.; Zaghary, W. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 141, 603–614. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.10.016 |

| 32. | Bondock, S.; Alqahtani, S.; Fouda, A. M. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2021, 58, 56–73. doi:10.1002/jhet.4148 |

| 41. | Mosmann, T. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4 |

| 7. | Schmidt, P.; Eichenberger, K.; Wilhelm, M. Angew. Chem. 1961, 73, 15–22. doi:10.1002/ange.19610730105 |

| 8. | Cheng, C. C.; Robins, R. K.; Cheng, K. C.; Lin, D. C. J. Pharm. Sci. 1968, 57, 1044–1045. doi:10.1002/jps.2600570634 |

| 9. | Cheng, C. C.; Elslager, E. F.; Werbel, L. M.; Leopold, W. R., III. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29, 1544–1547. doi:10.1021/jm00158a041 |

| 10. | Mitschker, A.; Wedemeyer, K. Synthesis 1988, 517–520. doi:10.1055/s-1988-27622 |

| 11. | Ried, W.; Aboul-Fetouh, S. Chem.-Ztg. 1989, 113, 181–183. |

| 12. | Srivastava, R.; Mishra, A.; Pratap, R.; Bhakuni, D. S.; Srimal, R. C. Thromb. Res. 1989, 54, 741–749. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(89)90138-2 |

| 13. | Maquestiau, A.; Banneux, F.; Vanden Eynde, J. J. Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg. 1991, 100, 401–406. doi:10.1002/bscb.19911000507 |

| 14. | Kelley, J. L.; Wilson, D. C.; Styles, V. L.; Soroko, F. E.; Cooper, B. R. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1995, 32, 1417–1421. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570320502 |

| 15. | Mekheimer, R. A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1999, 2183–2188. doi:10.1039/a901521c |

| 16. | Mekheimer, R. A. Synth. Commun. 2001, 31, 1971–1982. doi:10.1081/scc-100104413 |

| 17. | Döpp, H.; Döpp, D. Sci. Synth. 2004, 17, 223–355. doi:10.1055/sos-sd-017-00001 |

| 18. | Bondock, S.; Rabie, R.; Etman, H. A.; Fadda, A. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 2122–2129. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.12.009 |

| 19. | Li, H.-b.; Zhu, Y.-q.; Song, X.-w.; Hu, F.-z.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.-h.; Niu, Z.-x.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.-h.; Song, H.-b.; Zou, X.-m.; Yang, H.-z. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9535–9542. doi:10.1021/jf801774k |

| 20. | Lei, B.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Du, J.; Liu, H.; Yao, X. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 9593–9598. doi:10.1021/jf902010g |

| 21. | Roy, K.; Paul, S. J. Mol. Model. 2010, 16, 137–153. doi:10.1007/s00894-009-0528-8 |

| 22. | Colomer, J. P.; Moyano, E. L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1561–1565. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.01.040 |

| 23. | Mironovich, L. M.; Shcherbinin, D. V. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 50, 1860–1862. doi:10.1134/s1070428014120306 |

| 24. | Bondock, S.; Tarhoni, A. E.-G.; Fadda, A. A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2015, 52, 346–351. doi:10.1002/jhet.2041 |

| 25. | Mironovich, L. M.; Shcherbinin, D. V. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 52, 294–297. doi:10.1134/s1070428016020238 |

| 26. | Dawood, K. M.; Sayed, S. M.; Raslan, M. A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 2405–2416. doi:10.1002/jhet.2836 |

| 27. | Fadda, A. A.; Rabie, R.; Etman, H. A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 1015–1023. doi:10.1002/jhet.2669 |

| 28. | Hassan, A. S.; Moustafa, G. O.; Awad, H. M. Synth. Commun. 2017, 47, 1963–1972. doi:10.1080/00397911.2017.1358368 |

| 29. | Nasr, T.; Bondock, S.; Youns, M.; Fayad, W.; Zaghary, W. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 141, 603–614. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.10.016 |

| 30. | Hassan, A. S.; Moustafa, G. O.; Askar, A. A.; Naglah, A. M.; Al-Omar, M. A. Synth. Commun. 2018, 48, 2761–2772. doi:10.1080/00397911.2018.1524492 |

| 31. | Sadchikova, E. V.; Alexeeva, D. L.; Nenajdenko, V. G. Mendeleev Commun. 2019, 29, 653–654. doi:10.1016/j.mencom.2019.11.016 |

| 32. | Bondock, S.; Alqahtani, S.; Fouda, A. M. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2021, 58, 56–73. doi:10.1002/jhet.4148 |

| 33. | Seela, F.; Lindner, M.; Glaçon, V.; Lin, W. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 4695–4700. doi:10.1021/jo040150i |

| 34. | Harb, A.-F. A.; Abbas, H. H.; Mostafa, F. H. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2005, 2, 115–123. doi:10.1007/bf03247202 |

| 37. | Reingruber, R.; Vanderheiden, S.; Muller, T.; Nieger, M.; Es-Sayed, M.; Bräse, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 3439–3442. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.184 |

| 4. | He, L.; Gilligan, P. J.; Zaczek, R.; Fitzgerald, L. W.; McElroy, J.; Shen, H.-S. L.; Saye, J. A.; Kalin, N. H.; Shelton, S.; Christ, D.; Trainor, G.; Hartig, P. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 449–456. doi:10.1021/jm9904351 |

| 5. | Nie, Z.; Perretta, C.; Erickson, P.; Margosiak, S.; Almassy, R.; Lu, J.; Averill, A.; Yager, K. M.; Chu, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 4191–4195. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.05.041 |

| 6. | Nie, Z.; Perretta, C.; Erickson, P.; Margosiak, S.; Lu, J.; Averill, A.; Almassy, R.; Chu, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 619–623. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.074 |

| 37. | Reingruber, R.; Vanderheiden, S.; Muller, T.; Nieger, M.; Es-Sayed, M.; Bräse, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 3439–3442. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.184 |

| 38. | Bräse, S.; Enders, D.; Köbberling, J.; Avemaria, F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 3413–3415. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19981231)37:24<3413::aid-anie3413>3.0.co;2-k |

| 39. | Nicolaou, K. C.; Li, H.; Boddy, C. N. C.; Ramanjulu, J. M.; Yue, T.-Y.; Natarajan, S.; Chu, X.-J.; Bräse, S.; Rübsam, F. Chem. – Eur. J. 1999, 5, 2584–2601. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(19990903)5:9<2584::aid-chem2584>3.0.co;2-b |

| 22. | Colomer, J. P.; Moyano, E. L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1561–1565. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.01.040 |

| 36. | Khutova, B. M.; Klyuchko, S. V.; Gurenko, A. O.; Vasilenko, A. N.; Balya, A. G.; Rusanov, E. B.; Brovarets, V. S. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2012, 48, 1251–1262. doi:10.1007/s10593-012-1128-6 |

| 22. | Colomer, J. P.; Moyano, E. L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 1561–1565. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.01.040 |

| 37. | Reingruber, R.; Vanderheiden, S.; Muller, T.; Nieger, M.; Es-Sayed, M.; Bräse, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 3439–3442. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.184 |

| 35. | Bretschneider, T.; Cerezo-Galvez, S.; Grondal, C.; Fischer, R.; Fuesslein, M.; Reinisch, P.; Gueclue, M.; Ilg, K.; Loesel, P.; Malsam, O. Heterocyclic compounds as pest control agents. WO Pat. Appl. WO 2015/135843 A1, Sept 17, 2015. |

| 18. | Bondock, S.; Rabie, R.; Etman, H. A.; Fadda, A. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 2122–2129. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.12.009 |

| 26. | Dawood, K. M.; Sayed, S. M.; Raslan, M. A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 2405–2416. doi:10.1002/jhet.2836 |

© 2021 Wippert et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the author(s) and source are credited and that individual graphics may be subject to special legal provisions.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms)