Abstract

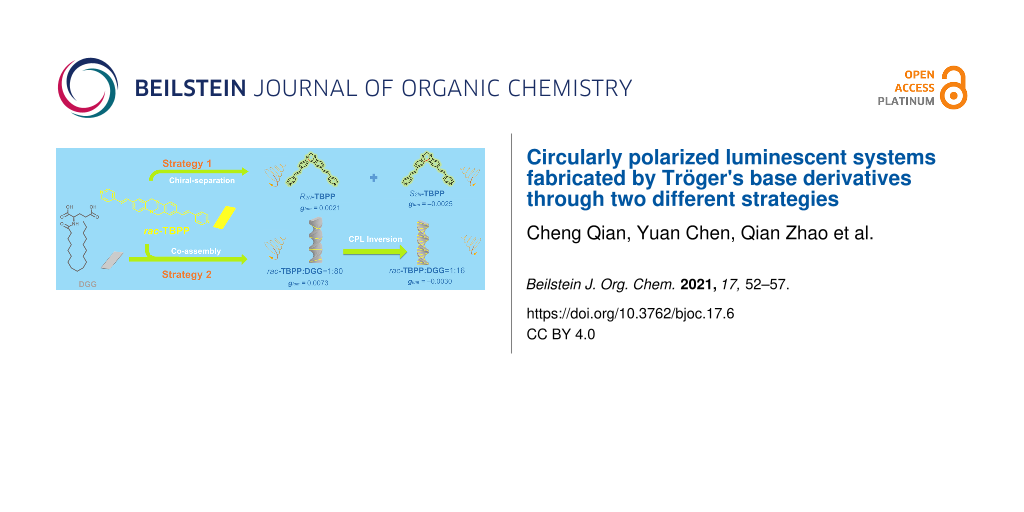

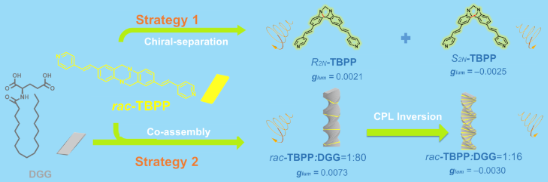

The Tröger's base derivative rac-TBPP was synthesized and separated into two enantiomers R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP by chiral column chromatography. These compounds show a strong circularly polarized luminescence with glum values of +0.0021, and −0.0025, respectively. The second way to fabricate the rac-TBPP-based CPL-active material is to co-gel the fluorescent rac-TBPP with a chiral ᴅ-glutamic acid gelator DGG by co-assembly strategy. At the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:80, the glum value of the co-gel was about three times higher than the glum values of R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP enantiomers. Interestingly, the CPL handedness of the rac-TBPP/DGG co-gel could be adjusted effectively by changing their stoichiometric ratios.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Recently, much effort has been devoted to constructing luminescent materials with efficient high emission in the solid state [1-3]. More and more types of fluorophores with aggregation-induced emission (AIE) characteristics have been discovered and applied in practice [4-6]. Among them, the fluorescent materials emitting circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) have attracted intensive interest owing to their wide applications in various researching fields including 3D displays, chiroptical materials, and so on [7-10]. Circular dichroism (CD) absorption spectra reflect the chirality of the fluorescent materials in the ground state, and circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) spectra reflect the chirality of fluorescent materials in the excited electronic state. Therefore, the CD and CPL spectrum are the two most important tools to test the chirality of luminescent materials [11,12].

As a useful building block in constructing functional materials [13,14], Tröger’s base (TB), first synthesized in 1887 [15], shows high controllability and obvious advantages. There are eleven sites in its framework that could be modified without considering the side chain. At the same time, the loose stacking of the TB unit and its derivatives, which is caused by its V-configuration could reduce the distance-dependent intermolecular quenching effect in the aggregation state [16]. Moreover, the large dihedral angle of TB (80–104°) [15] permits less self-absorption and a wider stokes shift [17]. Further, the steric hindrance and highly rigidity could reduce non-radiative transition and restrict the internal rotation [18]. More importantly, in the TB structure, its bridged methylene groups of the diazocine chiral nitrogen atoms prevent the inversion of the configuration, and two stable enantiomers could be formed and separated then. Although the TB shows excellent performance in constructing AIE materials, TB-based materials emitting CPL have rarely been reported so far. In general, the luminescent part and the chiral part are necessary to construct CPL-active materials [19-21], so the fluorescent Tröger's base derivatives rac-TBPP fall into our sight as the candidate to construct CPL-active materials. Herein, we take two stratgies to construct rac-TBPP-based CPL material. One stratgy is to separate non-CPL emission rac-TBPP into CPL-active enantiomers R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP, respectively. The other stratgy is to co-assemble the fluorescent rac-TBPP with the chiral ᴅ-glutamic acid gelator DGG to form the CPL-active co-gel. Interestingly, adjusting the stoichiometric ratios of rac-TBPP/DGG of the co-assembling system, the handedness of CPL-active co-gel can be controlled effectively (Scheme 1).

![[1860-5397-17-6-i1]](/bjoc/content/inline/1860-5397-17-6-i1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Scheme 1: Cartoon representative for rac-TBPP-based CPL-active systems fabricated through two strategies.

Scheme 1: Cartoon representative for rac-TBPP-based CPL-active systems fabricated through two strategies.

Results and Discussion

The synthetic routes of rac-TBPP are outlined in Supporting Information File 1, Scheme S1. Firstly, 2,8-dibromo-6H,12H-5,11-methanodibenzo[b,f][1,5]diazocine was synthesized according to the reported procedure [22]. Then, by Suzuki coupling reaction between 2,8-dibromo-6H,12H-5,11-methanodibenzo[b,f][1,5]diazocine and 4-vinylpyridine, rac-TBPP was successfully obtained in 51.8% yield. Detailed experiments and characterization were described in Supporting Information File 1 (Figures S1–S3). Firstly, rac-TBPP was separated into two fractions R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP by a chiralpak IB column using MeOH/DCM (80:20, v/v) as the eluent (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S5). The CD spectrum of the first fraction exhibited a positive Cotton effect at 352 nm, assigned to R2N-TBPP, while the second one showed a negative Cotton effect at the same wavelength, assigned to S2N-TBPP (Figure 1a) [23]. R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP were tested further by CPL spectroscopy, and the magnitude of the CPL emission was estimated by a luminescence dissymmetry factor (glum), defined as 2(IL − IR )/(IL + IR) where IL and IR are the intensity of the left-handed and right-handed CPL signals [24], respectively. Ranging from +2 for an ideal left-handed CPL to −2 for an ideal right-handed CPL, the glum value comes up to zero when no circular polarization of the luminescence was detected. The calculated value of glum of the CPL signals for R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP are +0.0021, and −0.0025, repectively (Figure 1b), which is larger than many small organic molecules [25].

![[1860-5397-17-6-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-17-6-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: Ground-state and excited-state chirality of R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP. (a) CD spectra of R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP. (b) CPL spectra of R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP excited at 350 nm.

Figure 1: Ground-state and excited-state chirality of R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP. (a) CD spectra of R2N-TBPP and S...

In order to avoid a tedious chiral separation of rac-TBPP, we tried to construct the CPL-active material by co-assembling the achiral fluorophore rac-TBPP with a chiral gelator DGG. In the CPL-active co-gels, noncovalent weak interactions might be formed between achiral fluorophores and a chiral gelator. So, the CPL emission of co-gels could be adjusted easily by external stimuli. The ᴅ-glutamic acid gelator DGG and its enantiomer LGG possess three hydrogen-bond sites, two carboxylic acid groups and one amide, which could be assemblied into the stable spiral structure by hydrogen-bond and other noncovlant interactions. DGG was synthesised by introducing an octadecyl moiety into the glutamic skeleton in 78.6% yield according to the reported route (Supporting Information File 1, Scheme S2) [26]. When rac-TBPP was mixed with DGG at molar ratios from 1:100 to 1:16 (rac-TBPP/DGG), transparent yellow co-gels were successfully formed by being heated to dissolve in chloroform, and then cooled to ambient temperature (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S6). Owing to the AIE effect of the TB unit the fluorescence intensity of these co-assembly co-gels enhanced sharply (Figure 2a). More interestingly, at the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:16, the CPL spectra of the co-gel shows a negative signal, while at the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:32 or higher, positive signals exhibiting left-handed CPL signals were observed (Figure 2b). At the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:80, the CPL spectra shows a positive signal with a glum value about +0.0073, which was almost three times higher than the glum value of TBPP enantiomers (Figure 2c). Compared with the co-gel at the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:80, a mirror symmetry was observed in the CPL spectra of the co-gel at the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/LGG = 1:80 (Figure 2d).

![[1860-5397-17-6-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-17-6-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: (a) Fluorescence spectra of rac-TBPP in solution (dash line) and in the rac-TBPP/DGG co-gels. (b) CPL spectra of the rac-TBPP/DGG co-gel at molar ratios from 1:100 to 1:16. (c) Plot of glum value of CPL signals versus ratios of rac-TBPP/DGG in the co-gel. (d) Mirror symmetry in CPL spectra of rac-TBPP/DGG co-gel (red line) and rac-TBPP/LGG (blue line) co-gel at the molar ratio of 1:80.

Figure 2: (a) Fluorescence spectra of rac-TBPP in solution (dash line) and in the rac-TBPP/DGG co-gels. (b) C...

rac-TBPP contains pyridine units, and the gelator DGG has the carboxyl groups. Therefore, hydrogen bonds might be formed between pyridine in rac-TBPP and the carboxyl groups in DGG. Moreover, the morphologies of rac-TBPP/DGG co-gels might be different due to the changing stoichiometric ratios. In order to get an indepth understanding on the inversion of CPL handedness, rac-TBPP/DGG co-gels at molar ratios of 1:16 and 1:80 were explored further by UV–vis and FTIR (fourier transform infrared) spectra. UV–vis absorption spectra of rac-TBPP/DGG co-gels exhibited a strong absorption band at 333 nm, assigned to the conjugated structure of benzene and pyridine in the rac-TBPP (Figure 3a). However, a red-shift broaden absorption band situated at 372 nm appears in the rac-TBPP/DGG co-gel, implying the formation of the ordered packing of rac-TBPP in supramolecular assemblies. At the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:80, The FTIR spectrum was similar to that of the DGG gel, in which νC=O bonds at 1729, 1691, and 1645 cm−1 reveal that the carboxyl acid groups of DGG could be involved in the formation of various hydrogen bonds (Figure 3b, Figure S7, Supporting Information File 1). At the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:16, the intensity of the peak at 1691 cm−1 decreases, and the peak at 1729 cm−1 brodens. A new peak adjacent to 1645 cm−1 appears at 1627 cm−1. The results demonstrate that some of the acid–acid hydrogen bonds between DGG molecules might be replaced by acid–pyridine hydrogen bonds between DGG and rac-TBPP [27]. In addition, the possible influence of the stoichiometric ratios to the morphologies of rac-TBPP/DGG co-gels was investigated using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). At the molar ratio of rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:80, the co-gel shows belt-like nanofibers (Figure 3c), while the fibrous morphology could not be observed at the molar ratio of 1:16 (Figure 3d). It indicates that two different kinds of supramolecular assemblies were formed at the ratios of rac-TBPP/DGG 1:80 and 1:16, respectively, which is also coincident with the inversion of the CPL responses. However, more detailed studies are still needed to clarify the relations between the morphology and CPL handedness.

![[1860-5397-17-6-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-17-6-3.jpg?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: (a) UV–vis absorption spectra of rac-TBPP and rac-TBPP/DGG co-gel (rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:80). (b) FTIR spectra of DGG and rac-TBPP/DGG co-gels at molar ratios of 1:80 and 1:16, respectively. SEM images of rac-TBPP/DGG co-gels at molar ratios of 1:80 (c) and 1:16 (d).

Figure 3: (a) UV–vis absorption spectra of rac-TBPP and rac-TBPP/DGG co-gel (rac-TBPP/DGG = 1:80). (b) FTIR s...

Conclusion

In conclusion, two strategies were demonstrated to obtain CPL-active materials based on the Tröger’s base derivative rac-TBPP. One method is to separate rac-TBPP into two enantiomers R2N-TBPP and S2N-TBPP, which emit strong circularly polarized luminescence. The other strategy is to co-gel the fluorescent rac-TBPP with a chiral ᴅ-glutamic acid gelator DGG by the co-assembly strategy. The cogels show significant CPL emission and stoichiometry-controlled inversion of chirality due to the hydrogen bonding interactions and packing modes in the supramolecular co-assemblies. Owing to TB special V-shaped structure, rigid conformation, and nitrogen stereogenic centers make it and its derivatives useful building blocks to construct CPL-active materials and to develop chiral phosphorescent materials in future.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental part. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.1 MB | Download |

References

-

Zhang, Z.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6028–6032. doi:10.1002/anie.201901882

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, C.; Chi, Z.; Chong, K. C.; Batsanov, A. S.; Yang, Z.; Mao, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, B. Nat. Mater. 2020. doi:10.1038/s41563-020-0797-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bolton, O.; Lee, K.; Kim, H.-J.; Lin, K. Y.; Kim, J. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 205–210. doi:10.1038/nchem.984

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lam, J. W. Y.; Tang, B. Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9888–9907. doi:10.1002/anie.201916729

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Song, N.; Wang, D.; Tang, B. Z. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 1144–1172. doi:10.1039/c9cs00495e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Roose, J.; Tang, B. Z.; Wong, K. S. Small 2016, 12, 6495–6512. doi:10.1002/smll.201601455

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Han, J.; Guo, S.; Lu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, W. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800538. doi:10.1002/adom.201800538

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zheng, H.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, S. X.-A.; Xu, Y. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2018, 30, 1705948. doi:10.1002/adma.201705948

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nitti, A.; Pasini, D. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2020, 32, 1908021. doi:10.1002/adma.201908021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Han, J.; You, J.; Li, X.; Duan, P.; Liu, M. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2017, 29, 1606503. doi:10.1002/adma.201606503

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Berova, N.; Bari, L. D.; Pescitelli, G. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 914–931. doi:10.1039/b515476f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sánchez-Carnerero, E. M.; Agarrabeitia, A. R.; Moreno, F.; Maroto, B. L.; Muller, G.; Ortiz, M. J.; de la Moya, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 13488–13500. doi:10.1002/chem.201501178

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rúnarsson, Ö. V.; Artacho, J.; Wärnmark, K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 7015–7041. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201201249

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dolenský, B.; Havlík, M.; Král, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3839–3858. doi:10.1039/c2cs15307f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tröger, J. J. Prakt. Chem. 1887, 36, 225–245. doi:10.1002/prac.18870360123

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yuan, C.-X.; Tao, X.-T.; Ren, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.-X.; Yu, W.-T.; Wang, L.; Jiang, M.-H. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 12811–12816. doi:10.1021/jp0711601

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xi, H.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, C.-X.; Li, Y.-X.; Wang, L.; Tao, X.-T.; Ma, X.-H.; Zhang, C.-F.; Hao, Y. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 45668–45678. doi:10.1039/c5ra07912h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yuan, R.; Li, M.-q.; Xu, J.-b.; Huang, S.-y.; Zhou, S.-l.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.-j.; Wu, H. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 4081–4084. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2016.05.042

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sang, Y.; Han, J.; Zhao, T.; Duan, P.; Liu, M. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2020, 32, 1900110. doi:10.1002/adma.201900110

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Takaishi, K.; Iwachido, K.; Takehana, R.; Uchiyama, M.; Ema, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6185–6190. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b02582

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liang, J.; Guo, P.; Qin, X.; Gao, X.; Ma, K.; Zhu, X.; Jin, X.; Xu, W.; Jiang, L.; Duan, P. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 3190–3198. doi:10.1021/acsnano.9b08408

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yuan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, H.; Tao, X. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 55577–55581. doi:10.1039/c7ra11228a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Y.; Cheng, M.; Hong, B.; Zhao, Q.; Qian, C.; Jiang, J.; Li, S.; Lin, C.; Wang, L. Front. Chem. (Lausanne, Switz.) 2019, 7, 383. doi:10.3389/fchem.2019.00383

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Riehl, J. P.; Richardson, F. S. Chem. Rev. 1986, 86, 1–16. doi:10.1021/cr00071a001

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ma, J.-L.; Peng, Q.; Zhao, C.-H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 15441–15454. doi:10.1002/chem.201903252

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bachl, J.; Mayr, J.; Sayago, F. J.; Cativiela, C.; Díaz Díaz, D. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 5294–5297. doi:10.1039/c4cc08593k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, P.; Lü, B.; Han, D.; Duan, P.; Liu, M.; Yin, M. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2194–2197. doi:10.1039/c8cc08924h

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 27. | Li, P.; Lü, B.; Han, D.; Duan, P.; Liu, M.; Yin, M. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2194–2197. doi:10.1039/c8cc08924h |

| 1. | Zhang, Z.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6028–6032. doi:10.1002/anie.201901882 |

| 2. | Chen, C.; Chi, Z.; Chong, K. C.; Batsanov, A. S.; Yang, Z.; Mao, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, B. Nat. Mater. 2020. doi:10.1038/s41563-020-0797-2 |

| 3. | Bolton, O.; Lee, K.; Kim, H.-J.; Lin, K. Y.; Kim, J. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 205–210. doi:10.1038/nchem.984 |

| 13. | Rúnarsson, Ö. V.; Artacho, J.; Wärnmark, K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 7015–7041. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201201249 |

| 14. | Dolenský, B.; Havlík, M.; Král, V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3839–3858. doi:10.1039/c2cs15307f |

| 25. | Ma, J.-L.; Peng, Q.; Zhao, C.-H. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 15441–15454. doi:10.1002/chem.201903252 |

| 11. | Berova, N.; Bari, L. D.; Pescitelli, G. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 914–931. doi:10.1039/b515476f |

| 12. | Sánchez-Carnerero, E. M.; Agarrabeitia, A. R.; Moreno, F.; Maroto, B. L.; Muller, G.; Ortiz, M. J.; de la Moya, S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 13488–13500. doi:10.1002/chem.201501178 |

| 26. | Bachl, J.; Mayr, J.; Sayago, F. J.; Cativiela, C.; Díaz Díaz, D. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 5294–5297. doi:10.1039/c4cc08593k |

| 7. | Han, J.; Guo, S.; Lu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, W. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800538. doi:10.1002/adom.201800538 |

| 8. | Zheng, H.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, S. X.-A.; Xu, Y. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2018, 30, 1705948. doi:10.1002/adma.201705948 |

| 9. | Nitti, A.; Pasini, D. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2020, 32, 1908021. doi:10.1002/adma.201908021 |

| 10. | Han, J.; You, J.; Li, X.; Duan, P.; Liu, M. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2017, 29, 1606503. doi:10.1002/adma.201606503 |

| 23. | Chen, Y.; Cheng, M.; Hong, B.; Zhao, Q.; Qian, C.; Jiang, J.; Li, S.; Lin, C.; Wang, L. Front. Chem. (Lausanne, Switz.) 2019, 7, 383. doi:10.3389/fchem.2019.00383 |

| 4. | Zhao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lam, J. W. Y.; Tang, B. Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9888–9907. doi:10.1002/anie.201916729 |

| 5. | Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Song, N.; Wang, D.; Tang, B. Z. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 1144–1172. doi:10.1039/c9cs00495e |

| 6. | Roose, J.; Tang, B. Z.; Wong, K. S. Small 2016, 12, 6495–6512. doi:10.1002/smll.201601455 |

| 24. | Riehl, J. P.; Richardson, F. S. Chem. Rev. 1986, 86, 1–16. doi:10.1021/cr00071a001 |

| 17. | Xi, H.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, C.-X.; Li, Y.-X.; Wang, L.; Tao, X.-T.; Ma, X.-H.; Zhang, C.-F.; Hao, Y. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 45668–45678. doi:10.1039/c5ra07912h |

| 19. | Sang, Y.; Han, J.; Zhao, T.; Duan, P.; Liu, M. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2020, 32, 1900110. doi:10.1002/adma.201900110 |

| 20. | Takaishi, K.; Iwachido, K.; Takehana, R.; Uchiyama, M.; Ema, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6185–6190. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b02582 |

| 21. | Liang, J.; Guo, P.; Qin, X.; Gao, X.; Ma, K.; Zhu, X.; Jin, X.; Xu, W.; Jiang, L.; Duan, P. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 3190–3198. doi:10.1021/acsnano.9b08408 |

| 22. | Yuan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, H.; Tao, X. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 55577–55581. doi:10.1039/c7ra11228a |

| 16. | Yuan, C.-X.; Tao, X.-T.; Ren, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.-X.; Yu, W.-T.; Wang, L.; Jiang, M.-H. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 12811–12816. doi:10.1021/jp0711601 |

| 18. | Yuan, R.; Li, M.-q.; Xu, J.-b.; Huang, S.-y.; Zhou, S.-l.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.-j.; Wu, H. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 4081–4084. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2016.05.042 |

© 2021 Qian et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the author(s) and source are credited and that individual graphics may be subject to special legal provisions.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms)