Abstract

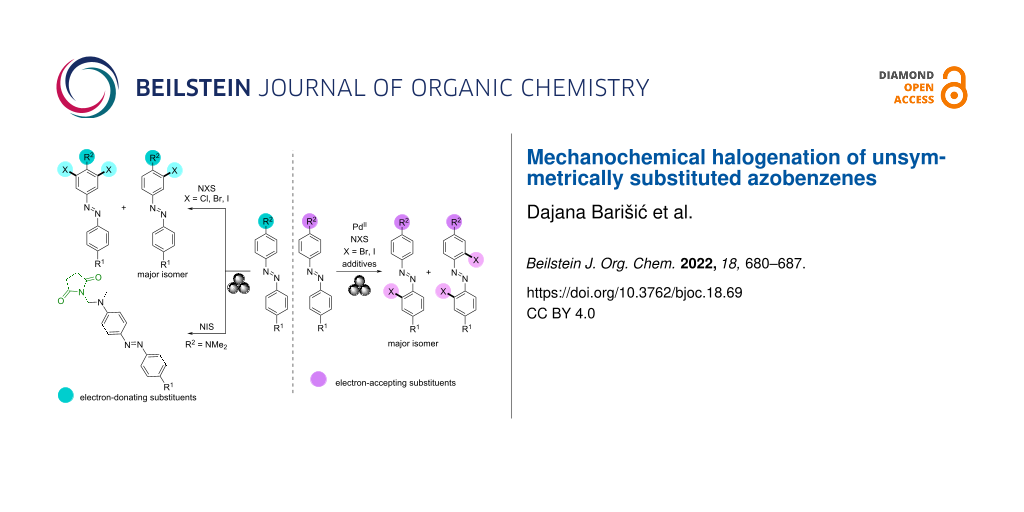

The direct and selective mechanochemical halogenation of C–H bonds in unsymmetrically substituted azobenzenes using N-halosuccinimides as the halogen source under neat grinding or liquid-assisted grinding conditions in a ball mill has been described. Depending on the azobenzene substrate used, halogenation of the C–H bonds occurs in the absence or only in the presence of PdII catalysts. Insight into the reaction dynamics and characterization of the products was achieved by in situ Raman and ex situ NMR spectroscopy and PXRD analysis. A strong influence of the different 4,4’-substituents of azobenzene on the halogenation time and mechanism was found.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Electrophilic aromatic substitution [1-3] and ligand-directed transition-metal-catalyzed reactions [4-8] are among the most widely used synthetic approaches for the preparation of halogenated arenes. They are important precursors in cross-coupling reactions [9-19] or components of pharmaceuticals and biologically active molecules [20,21]. The synthetic aspects of both approaches in solution are well established.

The need for green and sustainable chemistry [22] has led to the development and synthetic application of solid-state methods [23-46], particularly ball milling [26-46], which has proven to be an environmentally friendly and powerful alternative to conventional solvent-based protocols, offering unique advantages in terms of sustainability, reaction times, yields, reactant solubility, selectivity, and chemical reactivity. Although ball milling methods are widely used for the synthesis of various classes of compounds [26-46], their application in the synthesis of halogenated arenes is still scarce.

In 2015, Bolm and Hernandez reported the halogenation of 2-phenylpyridine in a ball mill using [Cp*RhCl2]2 in combination with AgSbF6 as catalyst and N-halosuccinimide (NXS, X = Br, I) as halogen source [47]. Two years later in 2017, Eslami's group applied a ball-milling method to synthesize aryl bromides and α-bromoketones with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and MCM-41-SO3H catalyst and no liquid additives [48]. In 2018, Wang and co-workers developed the ball-milling protocol for the ortho-halogenation of acetanilide with NXS (X = Cl, Br, I) using Pd(OAc)2 as precatalyst in the presence of p-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH) as an additive under solvent-free conditions [49]. Recently, Mal and Bera reported the utilization of NXS (X = Br, Cl) as bifunctional reagents for the solvent-free synthesis of phenanthridinones via a cascaded oxidative C–N coupling followed by a halogenation reaction [50].

Only recently, our group carried out a detailed synthetic and mechanistic study of the mechanochemical PdII-catalyzed bromination of unsubstituted azobenzene (L1) by N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) under neat grinding (NG) and liquid-assisted grinding (LAG) conditions in a ball mill [51]. Insight into the dynamics of the formation of reaction intermediates and products was obtained by in situ Raman monitoring that provided information on the nature of the catalytically active PdII species, cyclopalladated intermediates, and products (Figure 1). The monitoring results confirmed the crucial role of TsOH and acetonitrile (MeCN) as additives in the catalytic bromination of the C–H bond in L1. The experimental results were supported by quantum-chemical calculations, which showed that four mechanistic pathways could be involved in this reaction [51]. Three of them involve oxidative addition followed by reductive elimination. Neutral NBS or the hydrogen bond complex NBS∙∙∙TsOH are bromine donors in two of them, while protonated NBS is engaged in the third. The fourth mechanism proceeds by electrophilic cleavage with neutral NBS or the hydrogen bond complex NBS∙∙∙TsOH as a bromine source.

Figure 1: Molecular structures of the monomeric cyclopalladated intermediate and brominated product observed during the bromination of L1 under LAG conditions [51].

Figure 1: Molecular structures of the monomeric cyclopalladated intermediate and brominated product observed ...

Here we present the mechanochemical selective halogenation of unsymmetrically substituted azobenzenes by NXS (X = Cl, Br, or I). The liquid-assisted grinding of para-halogenated derivatives of azobenzene with NXS and Pd(OAc)2 as precatalyst in the presence of TsOH and MeCN as solid and liquid additives, respectively, led to the ortho-halogenated products relative to the azo group of the azobenzenes. In situ Raman monitoring of these reactions confirmed that the most favorable reaction pathway is via the monomeric cyclopalladated intermediate, as in the halogenation reaction of unsubstituted L1 [51]. While the reactions of L1 and its para-halogenated derivatives were unsuccessful without the PdII catalyst and TsOH, the halogenation of azobenzenes with the strong electron-donating substituents in the para position occurred in the absence of the added PdII catalyst and additives, in the ortho position to the substituent, which is typical for the products of electrophilic aromatic substitution.

In addition, an additive- and solvent-free protocol without the added PdII catalyst was developed for the selective imidation of azobenzenes containing a dimethylamino group as substituent in the para position to the azo group.

Results and Discussion

Inspired by our findings on the mechanochemical halogenation of L1 [51] and the report of Ma and Tian on the bromination of symmetric and unsymmetric azobenzenes in MeCN [52], we investigated how substituents of different donor strength affect the selectivity, reactivity, and reaction pathways of halogenation of azobenzene substrates under mechanochemical conditions.

Halogenation of azobenzenes with strong electron-donating substituents

In contrast to the reactions of L1 [51], the halogenation of azobenzene substrates containing strong electron-donating substituents (4-methoxyazobenzene (L2), 4-aminoazobenzene (L3), 4-dimethylaminoazobenzene (L4), and 4-(dimethylamino)-4'-nitroazobenzene (L5)) with NXS (X = Cl and Br) occurred in the absence of the added PdII catalyst and additives. These reactions in most cases produced electrophilic substitution products that were halogenated in the ortho position(s) relative to the electron-donating substituent (Scheme 1 and Table 1), as confirmed by Raman (Figures S14–S22 in Supporting Information File 1) and NMR spectroscopy (Figures S40–S76 in Supporting Information File 1). All experiments were performed without additional oxidants and solid or liquid additives. The presence of the PdII-catalyst in the reactions of L2–5 with NXS resulted predominantly in LnX-I products or a mixture of products that were mono- or dihalogenated at the ortho and meta-position(s) relative to the electron-donating substituent, which may be attributed to competition between PdII-catalyzed reactions and uncatalyzed electrophilic substitution.

Scheme 1: Halogenation of azobenzenes with strong electron-donating substituents.

Scheme 1: Halogenation of azobenzenes with strong electron-donating substituents.

Table 1: Halogenation of azobenzenes with strong electron-donating substituents.a

| Entry | Reactant | NXS | Product | t [h] | Yield [%]b |

| 1 | L2 | NCS | – | 7 | – |

| 2 | L3 | NCS | L3Cl-I | 1 | 46 (34) |

| 3 | L4 | NCS | L4Cl-I | 1 | 85 (73) |

| 4 | L5 | NCS |

L5Cl-I

L5Cl-II |

15 |

83 (72)

16 (8)c |

| 5 | L2 | NBS | L2Br-I | 15 | 96 (90) |

| 6 | L3 | NBS | L3Br-I | 1 | 72 (54) |

| 7 | L4 | NBS | L4Br-I | 1 | 79 (67) |

| 8 | L5 | NBS | L5Br-I | 7 | 53 (37) |

| 9 | L2 | NIS | – | 7 | – |

| 10 | L3 | NIS | L3I-I | 1 | 30 (21) |

| 11 | L4 | NIS | L4-III | 1 | 39 (29) |

| 12 | L5 | NIS | L5-III | 5 | 38 (31) |

aReaction conditions: 14 mL PMMA jar, mixer mill, one nickel bound tungsten carbide milling ball (7 mm in diameter, 3.9 g), 30 Hz, L2–5 (0.50 mmol), NXS (0.60 mmol), SiO2 (250 mg); bdetermined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,4-dinitrobenzene as the internal standard, with isolated yield given in parentheses; cyield calculated with respect to L5.

Our results are consistent with those reported by Sanford's group for the halogenation of various substrates by NXS with and without PdII catalyst [53]. Most of these reactions were carried out in MeCN and AcOH solutions at 100–120 °C. In contrast, the bromination of 4-methoxyazobenzene by NBS in MeCN at ambient temperature, reported by Tian and Ma [52], resulted in an electrophilic monobrominated product as a single isomer in both the catalyzed and uncatalyzed reactions.

Neat grinding of L3 and L4 with NCS produced the monochlorinated products L3Cl-I and L4Cl-I as single isomers within one hour (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). In contrast, the reaction of L5 with NCS resulted in a mixture of mono- and dichlorinated regioisomers (L5Cl-I and L5Cl-II) (Scheme 1 and Table 1, entry 4). The chlorination of L3 substrate with a primary amine as substituent gave the monochlorinated product L3Cl-I in 46% yield, while the yields of L4Cl-I and L5Cl-I were 85% and 83%, respectively (Table 1, entries 2–4). Although both substrates L4 and L5 contain a tertiary amine as a substituent (NMe2), the chlorination of L5 proceeded much more slowly (Table 1, entries 3 and 4).

Neither NCS nor NIS yielded halogenated products with substrate L2 (Table 1, entries 1 and 9). However, the reaction of L2 with NBS gave the monobrominated product L2Br-I in 96% yield after 15 hours of milling (Figure 2, Table 1, entry 5). The yield of this reaction was higher than the analogous reaction in MeCN solution (90% isolated yield under the mechanochemical conditions compared to 72% in MeCN solution) [52]. In situ Raman monitoring of the bromination of L2 confirmed its conversion to the product L2Br-I (Figure 2). The formation of L2Br-I was accompanied by the intensity decrease of L2 ν(N=N) and ν(C–N) bands in the range 1400–1450 and 1080–1200 cm−1, respectively. Compounds L2 and L2Br-I were identified in the reaction mixture by the Raman spectra of isolated L2 and L2Br-I (Figure 2c).

![[1860-5397-18-69-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-18-69-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: a) Two-dimensional (2D) plot of the time-resolved Raman monitoring of NG of L2 (0.50 mmol) with NBS (0.60 mmol) and SiO2 (250 mg). b) Reaction profile derived from multivariate curve analysis - alternating least squares fitting (MCR-ALS analysis). c) Extracted Raman spectra of species observed during Raman monitoring.

Figure 2: a) Two-dimensional (2D) plot of the time-resolved Raman monitoring of NG of L2 (0.50 mmol) with NBS...

Neat grinding of L3, L4, and L5 with NBS also produced the monobrominated products in yields ranging from 53 to 79% within one and seven hours, respectively (Table 1, entries 6–8).

The reaction of L3 with NIS resulted in the monoiodinated product in a low yield of 30% after one hour of milling (Table 1, entry 10 and Figures S77–S81 in Supporting Information File 1). Interestingly, in the reactions of L4 and L5 with NIS, instead of the halogenation of the aromatic C–H bond, imidation of the aliphatic C–H bond was observed. Imides are among the most studied functional groups, and new methods for their preparation, especially by environmentally friendly protocols, are of great synthetic importance in organic chemistry [54].

The succinimide products L4-III and L5-III (Table 1, entries 11 and 12) were obtained within one and five hours in 39 and 38% yields, respectively, as confirmed by NMR spectroscopy (Figures S82–S91 in Supporting Information File 1). Additional support for the formation of succinimide products was provided by the molecular structure of L4-III, resolved by single-crystal X-ray analysis (Figure 3 and Figure S33 and Table S1 in Supporting Information File 1). The molecular structure of L4-III showed that imidation occurred at the methyl group of the NMe2 substituent. Analogous succinimide species were also observed in the reaction of N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine with NIS in ethyl acetate [55] or N,N-dimethylamides and N,N-dimethylamines with NBS in carbon tetrachloride [56].

![[1860-5397-18-69-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-18-69-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: Experimental X-ray molecular structure of succinimide product L4-III.

Figure 3: Experimental X-ray molecular structure of succinimide product L4-III.

The reactivity trend of electron-rich azobenzenes L2–5 toward NXS was also investigated. Results of competition experiments clearly demonstrated that in the case of NCS their reactivity decreases in the order: L4 > L3 > L5 (Figures S1 and S2 in Supporting Information File 1), in the case of NBS in the order: L3 > L4 > L5 >> L2 (Figures S3–S6 in Supporting Information File 1), and in the case of NIS in the order: L4 >> L5 for the succinimide products (Figure S7 in Supporting Information File 1). The presence of an electron-accepting substituent (NO2) at the para position of the second phenyl ring in L5 significantly slowed the halogenation reaction and impaired the reactivity of the azobenzene. This result suggests that NO2 has a long-range effect that spreads through the azobenzene skeleton. Compared to the bromination of substrates L3–5 containing amino substituents, the analogous reaction of L2 is slower because the methoxy substituent has weaker donor strength than amino substituents [57].

The protocols described above provide a solvent- and additive-free approach without added PdII catalysts for the halogenation of Csp2–H and imidation of Csp3–H bonds of azobenzenes with electron-donating substituents by electrophilic activation with NXS.

Halogenation of azobenzenes with electron-accepting substituents

Using the optimal parameters for the mechanochemical bromination and iodination of L1 [51], we investigated the halogenation of azobenzene substrates with electron-accepting substituents at the para position relative to the azo group: 4-chloroazobenzene (L6), 4-bromoazobenzene (L7), and 4-iodoazobenzene (L8) (Scheme 2 and Table 2).

Scheme 2: PdII-catalyzed halogenation of azobenzene and its para-halogenated derivatives.

Scheme 2: PdII-catalyzed halogenation of azobenzene and its para-halogenated derivatives.

Table 2: PdII-catalyzed halogenation of L1 [51] and its para-halogenated derivatives (L6–8).a

| Entry | Reactant | NXS | Product | t [h] | Yield [%]b |

| 1 | L1 [51] | NCS | – | 17 | – |

| 2 | L6 | NCS | – | 17 | – |

| 3 | L7 | NCS | – | 17 | – |

| 4 | L8 | NCS | – | 17 | – |

| 5 | L1 [51] | NBS | L1Br-IV | 4 | 83 (74) |

| 6 | L6 | NBS | L6Br-IV | 6 | 73 (59) |

| 7 | L7 | NBS | L7Br-IV | 8 | 72 (60) |

| 8 | L8 | NBS | L8Br-IV | 8 | 62 (55) |

| 9 | L1 [51] | NIS |

L1I-IV

L1I-V |

4 |

38 (35)

43 (28)c |

| 10 | L6 | NIS |

L6I-IV

L6I-V |

6 |

66 (63)

17 (11)c |

| 11 | L7 | NIS |

L7I-IV

L7I-V |

5 |

69 (59)

19 (8)c |

| 12 | L8 | NIS |

L8I-IV

L8I-V |

7 |

52 (45)

19 (17)c |

aReaction conditions: 14 mL PMMA jar, mixer mill, one nickel bound tungsten carbide milling ball (7 mm in diameter, 3.9 g), 30 Hz, L1 and L6–8 (0.50 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (5 mol %), NXS (0.60 mmol), TsOH (0.25 mmol), MeCN (15 µL), SiO2 (250 mg); bdetermined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,4-dinitrobenzene as the internal standard, with isolated yield given in parentheses; cyield calculated with respect to L1 or L6–8.

The synthetic protocols included milling the mixture of Ln/NXS/TsOH 1:1.2:0.5 equiv, 5 mol % Pd(OAc)2 precatalyst, and 15 µL MeCN as liquid additive. Under these conditions, the reactions of L6–8 with NBS resulted in moderate to good yields of monobrominated products LnBr-IV (Table 2, entries 6–8).

The bromination of L6–8 occurred regioselectively at the ortho position of the unsubstituted phenyl ring, as shown by NMR spectroscopy (Figures S92–S103 in Supporting Information File 1). The reaction times required for bromination increased in the order L1 < L6 < L7 = L8 (Table 2, entries 5–8). Dibrominated products LnBr-V were not detected in any of these reactions. Since the complex Pd(OTs)2(MeCN)2 was identified as the active catalyst, formed in situ, in the bromination reaction of L1 [51], the analogous reactions of L6–8 were carried out using Pd(OTs)2(MeCN)2 as the catalyst instead of Pd(OAc)2. As expected, the yields of LnBr-IV products were comparable to those obtained in the reactions with the Pd(OAc)2 precatalyst.

The PdII-catalyzed iodination of L6–8 was conducted with N-iodosuccinimide (NIS) as the iodine source. The reaction time for the iodination of L6 was the same as for the analogous bromination reaction (Table 2, entry 10). Iodination of L7 and L8 was completed within five and seven hours, respectively (Table 2, entries 11 and 12). Unlike bromination, iodination of L6–8 with NIS resulted in a mixture of the mono- and diiodinated products at the ortho positions of one or both phenyl rings (LnI-IV and LnI-V, Scheme 2 and Table 2, entries 10–12), as confirmed by NMR spectroscopy (Figures S104–S130 in Supporting Information File 1). Compared to L1 [51], iodination of its para-halogenated derivatives resulted in lower yields of diiodinated products (Table 2, entries 9–12) since the activation/halogenation of the C–H bond occurs preferentially at the unsubstituted azobenzene phenyl ring [57].

The reactions of L6–8 with N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) gave no chlorinated product, which was also observed in the reaction of L1 with NCS (Table 2, entries 1–4) [51].

Since the monomeric monopalladated tosylate complex of azobenzene I1-I was identified as an intermediate in the solid-state bromination of L1 (Figure 1) [51], the analogous complexes of L6 and L7 were prepared to investigate whether the halogenation of the para-halogenated azobenzene derivatives follows the reaction pathway of the bromination of L1. The molecular structures of the isolated monopalladated tosylate complexes I6-I and I7-I solved from laboratory powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data (Figure 4 and Figures S31 and S32 in Supporting Information File 1), are similar to that of complex I1-I [51] in which the palladium center is bound to the MeCN and tosylate (OTs) via nitrogen and oxygen, respectively, and to the azobenzene via the azo nitrogen and a carbon atom of the unsubstituted phenyl ring. The tosylate ion is at the trans position to the carbon atom.

![[1860-5397-18-69-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-18-69-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: Experimental X-ray molecular structure of the intermediate I6-I.

Figure 4: Experimental X-ray molecular structure of the intermediate I6-I.

In situ Raman monitoring of the bromination of L6–8 in the presence of 30 mol % PdII catalyst revealed a new band around 1380 cm−1 (Figure 5a and Figures S23–S27 in Supporting Information File 1). It was assigned to the characteristic ν(N=N) bands of the In-I intermediates, confirming that the bromination of L6–8 proceeds via monopalladated In-I intermediates as in the reactions of L1 (Figure 5a and Figures S23–S27 in Supporting Information File 1) [51].

![[1860-5397-18-69-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-18-69-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: a) In situ observation of I6-I during the time-resolved Raman monitoring of LAG of L6 (0.50 mmol) with NBS (0.6 mmol), TsOH (0.25 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (30 mol %), MeCN (15 μL), and SiO2 (250 mg). b) Two-dimensional (2D) plot of the time-resolved Raman monitoring of LAG of L6 (0.40 mmol) with Pd(OAc)2 (0.42 mmol), TsOH (0.42 mmol), MeCN (0.48 mmol, 25 µL), and SiO2 (250 mg). Only Raman spectra before fluorescence are shown in both parts.

Figure 5: a) In situ observation of I6-I during the time-resolved Raman monitoring of LAG of L6 (0.50 mmol) w...

To gain insight into the dynamics of the formation of cyclopalladated intermediates In-I, LAG reactions of Pd(OAc)2 with L6–8 and TsOH were performed using 25 µL of MeCN as a liquid additive in a molar ratio of 1:1:1 (Ln/Pd(OAc)2/TsOH). In situ Raman monitoring of C–H bond activation was possible for L6 and L7, while in the case of L8, fluorescence prevented a more detailed insight into this reaction. The monitoring results confirmed the complete conversion of azobenzenes L6 and L7 to their monopalladated products after about one hour of milling, as well as a reaction course similar to that of the analogous reaction of L1 [51] (Figure 5b and Figure S28 in Supporting Information File 1).

The isolated cyclopalladated intermediates I6-I and I7-I were tested as catalysts for the bromination of L6 and L7. The yields of halogenated products in these reactions are 64% for L6Br-I and 70% for L7Br-I, which are close to those obtained in the analogous reactions with Pd(OAc)2 as precatalyst, as confirmed by NMR spectroscopy.

The results of in situ and ex situ spectroscopic monitoring along with the structural characterization of the intermediates have shown that the mechanism of the halogenation of azobenzenes with electron-accepting substituents is consistent with the proposed mechanistic schemes for the bromination of the unsubstituted azobenzene L1 [51]. Thus, the halogenation of L6–8 begins with the formation of the catalytically active PdII species, Pd(OTs)2(MeCN)2, from Pd(OAc)2, TsOH, and MeCN. It is followed by the formation of monomeric cyclopalladated intermediates In-I, at which halogenation occurs. Based on the similarities between the halogenation of L6–8 and the bromination of L1 [51], we assumed that the four mechanistic pathways considered for the bromination of I1-I are also possible for the halogenation of I6-I, I7-I, and I8-I [51].

In addition, we also investigated the reactivity trend of azobenzene L1 and its para-halogenated derivatives L6–8 toward NBS or NIS. The competition experiments showed that the azobenzenes with electron-withdrawing substituents are much less reactive to halogenation than L1. The reactivity of azobenzenes in the case of NBS decreases in this order: L1 >> L6 > L7 ≈ L8 (Figures S8–S10 in Supporting Information File 1), and in the case of NIS in the order: L1 >> L6 ≈ L8 > L7 (Figures S11–S13 in Supporting Information File 1), indicating that the PdII-catalyzed halogenation of azobenzenes is strongly influenced by the nature of the azobenzene substituents.

Conclusion

We have applied a mechanochemical protocol for the halogenation of 4,4’-functionalized azobenzenes in a ball mill under NG or LAG conditions, using NXS (X = Cl, Br, and I) as the halogen source.

Halogenation of azobenzenes with strong electron-donating groups was carried out without an added PdII catalyst. These transformations, which take place via electrophilic aromatic substitution, resulted in products halogenated in the ortho position to the electron-donating groups. The reactions of azobenzenes containing a dimethylamino group as substituent with NIS led to imidation products. A different reactivity of the dimethylamino group compared to the other substituents was also observed in these reactions.

On the other hand, the halogenation of para-halogenated azobenzenes required the presence of the PdII catalyst and TsOH as additive. In situ spectroscopic monitoring of these reactions revealed that the PdII-catalyzed halogenation proceeds via monomeric cyclopalladated intermediates formed by activation of the C–H bond in azobenzenes with the in situ generated Pd(OTs)2(MeCN)2 catalyst. The described results indicate a strong dependence of the halogenation outcome of C–H bonds in 4,4’-functionalized azobenzenes on the nature of their substituents.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Detailed experimental procedures, complete characterization data for new compounds, X-ray structures of compounds, and the results of in situ Raman monitoring. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 7.8 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: X-ray crystallographic data. | ||

| Format: CIF | Size: 397.5 KB | Download |

References

-

Taylor, R. Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

De la Mare, P. B. D. Electrophilic Halogenation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Börgel, J.; Tanwar, L.; Berger, F.; Ritter, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16026–16031. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b09208

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ackermann, L. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1315–1345. doi:10.1021/cr100412j

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lyons, T. W.; Sanford, M. S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1147–1169. doi:10.1021/cr900184e

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, X.-H.; Park, H.; Hu, J.-H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Q.-L.; Wang, B.-L.; Sun, B.; Yeung, K.-S.; Zhang, F.-L.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 888–896. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b11188

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Powers, D. C.; Ritter, T. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 302–309. doi:10.1038/nchem.246

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhu, R.-Y.; Saint-Denis, T. G.; Shao, Y.; He, J.; Sieber, J. D.; Senanayake, C. H.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5724–5727. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b02196

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Petrone, D. A.; Ye, J.; Lautens, M. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8003–8104. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00089

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nattmann, L.; Saeb, R.; Nöthling, N.; Cornella, J. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 6–13. doi:10.1038/s41929-019-0392-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ayogu, J. I.; Onoabedje, E. A. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 5233–5255. doi:10.1039/c9cy01331h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhai, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Fan, M.; Lai, Y.; Ma, D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4964–4969. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00493

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hartwig, J. F. Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of Aryl Ethers and Related Compounds Containing S and Se. In Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis; Negishi, E., Ed.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp 1051–1106. doi:10.1002/0471212466.ch43

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stille, J. K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1986, 25, 508–524. doi:10.1002/anie.198605081

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Heck, R. F. Synlett 2006, 2855–2860. doi:10.1055/s-2006-951536

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Suzuki, A. Chem. Commun. 2005, 4759–4763. doi:10.1039/b507375h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Muci, A. R.; Buchwald, S. L. Practical Palladium Catalysts for C-N and C-O Bond Formation. In Cross-Coupling Reactions; Miyaura, N., Ed.; Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol. 219; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2002; pp 131–209. doi:10.1007/3-540-45313-x_5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hartwig, J. F. Synlett 2006, 1283–1294. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939728

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hartwig, J. F. Nature 2008, 455, 314–322. doi:10.1038/nature07369

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Evans, D. A.; Katz, J. L.; Peterson, G. S.; Hintermann, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 12411–12413. doi:10.1021/ja011943e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pelletier, J. C.; Youssefyeh, R. D.; Campbell, H. F. Substituted Saturated and Unsaturated Indole Quinoline and Benzazepine Carboxamides and Their Use as Pharmacological Agents. U.S. Pat. Appl. US4920219A, April 24, 1990.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, C.-J.; Trost, B. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 13197–13202. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804348105

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cliffe, M. J.; Mottillo, C.; Stein, R. S.; Bučar, D.-K.; Friščić, T. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2495–2500. doi:10.1039/c2sc20344h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Halasz, I.; Budimir, A.; Užarević, K.; Lukin, S.; Monas, A.; Emmerling, F.; Plavec, J.; Ćurić, M. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 5342–5351. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00422

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Monas, A.; Užarević, K.; Halasz, I.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 12960–12963. doi:10.1039/c6cc06062e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

James, S. L.; Adams, C. J.; Bolm, C.; Braga, D.; Collier, P.; Friščić, T.; Grepioni, F.; Harris, K. D. M.; Hyett, G.; Jones, W.; Krebs, A.; Mack, J.; Maini, L.; Orpen, A. G.; Parkin, I. P.; Shearouse, W. C.; Steed, J. W.; Waddell, D. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 413–447. doi:10.1039/c1cs15171a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Wang, G.-W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7668–7700. doi:10.1039/c3cs35526h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Porcheddu, A.; Colacino, E.; De Luca, L.; Delogu, F. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8344–8394. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c00142

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Schumacher, C.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16357–16360. doi:10.1002/anie.202003565

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4007–4019. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02887

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hernández, J. G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 17157–17165. doi:10.1002/chem.201703605

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 317–324. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.021

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Howard, J. L.; Cao, Q.; Browne, D. L. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3080–3094. doi:10.1039/c7sc05371a

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Andersen, J.; Mack, J. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1435–1443. doi:10.1039/c7gc03797j

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Pickhardt, W.; Grätz, S.; Borchardt, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 12903–12911. doi:10.1002/chem.202001177

and references cited therein.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Ingner, F. J. L.; Giustra, Z. X.; Novosedlik, S.; Orthaber, A.; Gates, P. J.; Dyrager, C.; Pilarski, L. T. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 5648–5655. doi:10.1039/d0gc02263b

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hermann, G. N.; Unruh, M. T.; Jung, S.-H.; Krings, M.; Bolm, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10723–10727. doi:10.1002/anie.201805778

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Cheng, H.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6284–6287. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02973

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Cheng, H.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 1800–1804. doi:10.1002/adsc.201800161

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hermann, G. N.; Bolm, C. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4592–4596. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b00582

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hermann, G. N.; Jung, C. L.; Bolm, C. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2520–2523. doi:10.1039/c7gc00499k

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Yu, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, C.; Su, W. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 1009–1021. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02951

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Rightmire, N. R.; Hanusa, T. P. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 2352–2362. doi:10.1039/c5dt03866a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Juribašić, M.; Užarević, K.; Gracin, D.; Ćurić, M. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 10287–10290. doi:10.1039/c4cc04423a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Bjelopetrović, A.; Lukin, S.; Halasz, I.; Užarević, K.; Đilović, I.; Barišić, D.; Budimir, A.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10672–10682. doi:10.1002/chem.201802403

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Bjelopetrović, A.; Robić, M.; Halasz, I.; Babić, D.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2019, 38, 4479–4484. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00626

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12582–12584. doi:10.1039/c5cc04423e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ghanbari, N.; Ghafuri, H.; Esmaili Zand, H. R.; Eslami, M. SynOpen 2017, 1, 143–146. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1590959

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, Z.; Xu, H.; Wang, G.-W. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 430–435. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.31

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bera, S. K.; Mal, P. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 14144–14159. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c01742

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] -

Ma, X.-T.; Tian, S.-K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 337–340. doi:10.1002/adsc.201200902

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kalyani, D.; Dick, A. R.; Anani, W. Q.; Sanford, M. S. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 11483–11498. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.06.075

Return to citation in text: [1] -

de Figueiredo, R. M.; Suppo, J.-S.; Campagne, J.-M. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12029–12122. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00237

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, X.-J.; Amuti, A.; Wusiman, A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 5002–5008. doi:10.1002/adsc.202000796

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Caristi, C.; Ferlazzo, A.; Gattuso, M. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1984, 281–285. doi:10.1039/p19840000281

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bjelopetrović, A.; Barišić, D.; Duvnjak, Z.; Džajić, I.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Halasz, I.; Martínez, M.; Budimir, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 17123–17133. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02418

Return to citation in text: [1] [2]

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 1. | Taylor, R. Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990. |

| 2. | De la Mare, P. B. D. Electrophilic Halogenation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. |

| 3. | Börgel, J.; Tanwar, L.; Berger, F.; Ritter, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16026–16031. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b09208 |

| 22. | Li, C.-J.; Trost, B. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 13197–13202. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804348105 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 20. | Evans, D. A.; Katz, J. L.; Peterson, G. S.; Hintermann, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 12411–12413. doi:10.1021/ja011943e |

| 21. | Pelletier, J. C.; Youssefyeh, R. D.; Campbell, H. F. Substituted Saturated and Unsaturated Indole Quinoline and Benzazepine Carboxamides and Their Use as Pharmacological Agents. U.S. Pat. Appl. US4920219A, April 24, 1990. |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 9. | Petrone, D. A.; Ye, J.; Lautens, M. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8003–8104. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00089 |

| 10. | Nattmann, L.; Saeb, R.; Nöthling, N.; Cornella, J. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 6–13. doi:10.1038/s41929-019-0392-6 |

| 11. | Ayogu, J. I.; Onoabedje, E. A. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 5233–5255. doi:10.1039/c9cy01331h |

| 12. | Zhai, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Fan, M.; Lai, Y.; Ma, D. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4964–4969. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00493 |

| 13. | Hartwig, J. F. Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of Aryl Ethers and Related Compounds Containing S and Se. In Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis; Negishi, E., Ed.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp 1051–1106. doi:10.1002/0471212466.ch43 |

| 14. | Stille, J. K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1986, 25, 508–524. doi:10.1002/anie.198605081 |

| 15. | Heck, R. F. Synlett 2006, 2855–2860. doi:10.1055/s-2006-951536 |

| 16. | Suzuki, A. Chem. Commun. 2005, 4759–4763. doi:10.1039/b507375h |

| 17. | Muci, A. R.; Buchwald, S. L. Practical Palladium Catalysts for C-N and C-O Bond Formation. In Cross-Coupling Reactions; Miyaura, N., Ed.; Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol. 219; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2002; pp 131–209. doi:10.1007/3-540-45313-x_5 |

| 18. | Hartwig, J. F. Synlett 2006, 1283–1294. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939728 |

| 19. | Hartwig, J. F. Nature 2008, 455, 314–322. doi:10.1038/nature07369 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 4. |

Ackermann, L. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1315–1345. doi:10.1021/cr100412j

and references cited therein. |

| 5. |

Lyons, T. W.; Sanford, M. S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1147–1169. doi:10.1021/cr900184e

and references cited therein. |

| 6. | Liu, X.-H.; Park, H.; Hu, J.-H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Q.-L.; Wang, B.-L.; Sun, B.; Yeung, K.-S.; Zhang, F.-L.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 888–896. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b11188 |

| 7. | Powers, D. C.; Ritter, T. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 302–309. doi:10.1038/nchem.246 |

| 8. | Zhu, R.-Y.; Saint-Denis, T. G.; Shao, Y.; He, J.; Sieber, J. D.; Senanayake, C. H.; Yu, J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5724–5727. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b02196 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 47. | Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12582–12584. doi:10.1039/c5cc04423e |

| 49. | Liu, Z.; Xu, H.; Wang, G.-W. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 430–435. doi:10.3762/bjoc.14.31 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 26. | James, S. L.; Adams, C. J.; Bolm, C.; Braga, D.; Collier, P.; Friščić, T.; Grepioni, F.; Harris, K. D. M.; Hyett, G.; Jones, W.; Krebs, A.; Mack, J.; Maini, L.; Orpen, A. G.; Parkin, I. P.; Shearouse, W. C.; Steed, J. W.; Waddell, D. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 413–447. doi:10.1039/c1cs15171a |

| 27. | Wang, G.-W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7668–7700. doi:10.1039/c3cs35526h |

| 28. |

Porcheddu, A.; Colacino, E.; De Luca, L.; Delogu, F. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8344–8394. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c00142

and references cited therein. |

| 29. | Schumacher, C.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16357–16360. doi:10.1002/anie.202003565 |

| 30. |

Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4007–4019. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02887

and references cited therein. |

| 31. |

Hernández, J. G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 17157–17165. doi:10.1002/chem.201703605

and references cited therein. |

| 32. | Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 317–324. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.021 |

| 33. |

Howard, J. L.; Cao, Q.; Browne, D. L. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3080–3094. doi:10.1039/c7sc05371a

and references cited therein. |

| 34. | Andersen, J.; Mack, J. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1435–1443. doi:10.1039/c7gc03797j |

| 35. |

Pickhardt, W.; Grätz, S.; Borchardt, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 12903–12911. doi:10.1002/chem.202001177

and references cited therein. |

| 36. | Ingner, F. J. L.; Giustra, Z. X.; Novosedlik, S.; Orthaber, A.; Gates, P. J.; Dyrager, C.; Pilarski, L. T. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 5648–5655. doi:10.1039/d0gc02263b |

| 37. | Hermann, G. N.; Unruh, M. T.; Jung, S.-H.; Krings, M.; Bolm, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10723–10727. doi:10.1002/anie.201805778 |

| 38. | Cheng, H.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6284–6287. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02973 |

| 39. | Cheng, H.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 1800–1804. doi:10.1002/adsc.201800161 |

| 40. | Hermann, G. N.; Bolm, C. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4592–4596. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b00582 |

| 41. | Hermann, G. N.; Jung, C. L.; Bolm, C. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2520–2523. doi:10.1039/c7gc00499k |

| 42. | Yu, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, C.; Su, W. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 1009–1021. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02951 |

| 43. | Rightmire, N. R.; Hanusa, T. P. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 2352–2362. doi:10.1039/c5dt03866a |

| 44. | Juribašić, M.; Užarević, K.; Gracin, D.; Ćurić, M. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 10287–10290. doi:10.1039/c4cc04423a |

| 45. | Bjelopetrović, A.; Lukin, S.; Halasz, I.; Užarević, K.; Đilović, I.; Barišić, D.; Budimir, A.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10672–10682. doi:10.1002/chem.201802403 |

| 46. | Bjelopetrović, A.; Robić, M.; Halasz, I.; Babić, D.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2019, 38, 4479–4484. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00626 |

| 50. | Bera, S. K.; Mal, P. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 14144–14159. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.1c01742 |

| 57. | Bjelopetrović, A.; Barišić, D.; Duvnjak, Z.; Džajić, I.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Halasz, I.; Martínez, M.; Budimir, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 17123–17133. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02418 |

| 26. | James, S. L.; Adams, C. J.; Bolm, C.; Braga, D.; Collier, P.; Friščić, T.; Grepioni, F.; Harris, K. D. M.; Hyett, G.; Jones, W.; Krebs, A.; Mack, J.; Maini, L.; Orpen, A. G.; Parkin, I. P.; Shearouse, W. C.; Steed, J. W.; Waddell, D. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 413–447. doi:10.1039/c1cs15171a |

| 27. | Wang, G.-W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7668–7700. doi:10.1039/c3cs35526h |

| 28. |

Porcheddu, A.; Colacino, E.; De Luca, L.; Delogu, F. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8344–8394. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c00142

and references cited therein. |

| 29. | Schumacher, C.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16357–16360. doi:10.1002/anie.202003565 |

| 30. |

Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4007–4019. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02887

and references cited therein. |

| 31. |

Hernández, J. G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 17157–17165. doi:10.1002/chem.201703605

and references cited therein. |

| 32. | Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 317–324. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.021 |

| 33. |

Howard, J. L.; Cao, Q.; Browne, D. L. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3080–3094. doi:10.1039/c7sc05371a

and references cited therein. |

| 34. | Andersen, J.; Mack, J. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1435–1443. doi:10.1039/c7gc03797j |

| 35. |

Pickhardt, W.; Grätz, S.; Borchardt, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 12903–12911. doi:10.1002/chem.202001177

and references cited therein. |

| 36. | Ingner, F. J. L.; Giustra, Z. X.; Novosedlik, S.; Orthaber, A.; Gates, P. J.; Dyrager, C.; Pilarski, L. T. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 5648–5655. doi:10.1039/d0gc02263b |

| 37. | Hermann, G. N.; Unruh, M. T.; Jung, S.-H.; Krings, M.; Bolm, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10723–10727. doi:10.1002/anie.201805778 |

| 38. | Cheng, H.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6284–6287. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02973 |

| 39. | Cheng, H.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 1800–1804. doi:10.1002/adsc.201800161 |

| 40. | Hermann, G. N.; Bolm, C. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4592–4596. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b00582 |

| 41. | Hermann, G. N.; Jung, C. L.; Bolm, C. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2520–2523. doi:10.1039/c7gc00499k |

| 42. | Yu, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, C.; Su, W. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 1009–1021. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02951 |

| 43. | Rightmire, N. R.; Hanusa, T. P. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 2352–2362. doi:10.1039/c5dt03866a |

| 44. | Juribašić, M.; Užarević, K.; Gracin, D.; Ćurić, M. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 10287–10290. doi:10.1039/c4cc04423a |

| 45. | Bjelopetrović, A.; Lukin, S.; Halasz, I.; Užarević, K.; Đilović, I.; Barišić, D.; Budimir, A.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10672–10682. doi:10.1002/chem.201802403 |

| 46. | Bjelopetrović, A.; Robić, M.; Halasz, I.; Babić, D.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2019, 38, 4479–4484. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00626 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 23. | Cliffe, M. J.; Mottillo, C.; Stein, R. S.; Bučar, D.-K.; Friščić, T. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2495–2500. doi:10.1039/c2sc20344h |

| 24. | Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Halasz, I.; Budimir, A.; Užarević, K.; Lukin, S.; Monas, A.; Emmerling, F.; Plavec, J.; Ćurić, M. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 5342–5351. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00422 |

| 25. | Monas, A.; Užarević, K.; Halasz, I.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 12960–12963. doi:10.1039/c6cc06062e |

| 26. | James, S. L.; Adams, C. J.; Bolm, C.; Braga, D.; Collier, P.; Friščić, T.; Grepioni, F.; Harris, K. D. M.; Hyett, G.; Jones, W.; Krebs, A.; Mack, J.; Maini, L.; Orpen, A. G.; Parkin, I. P.; Shearouse, W. C.; Steed, J. W.; Waddell, D. C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 413–447. doi:10.1039/c1cs15171a |

| 27. | Wang, G.-W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7668–7700. doi:10.1039/c3cs35526h |

| 28. |

Porcheddu, A.; Colacino, E.; De Luca, L.; Delogu, F. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8344–8394. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c00142

and references cited therein. |

| 29. | Schumacher, C.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16357–16360. doi:10.1002/anie.202003565 |

| 30. |

Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4007–4019. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02887

and references cited therein. |

| 31. |

Hernández, J. G. Chem. – Eur. J. 2017, 23, 17157–17165. doi:10.1002/chem.201703605

and references cited therein. |

| 32. | Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 317–324. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.021 |

| 33. |

Howard, J. L.; Cao, Q.; Browne, D. L. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3080–3094. doi:10.1039/c7sc05371a

and references cited therein. |

| 34. | Andersen, J.; Mack, J. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1435–1443. doi:10.1039/c7gc03797j |

| 35. |

Pickhardt, W.; Grätz, S.; Borchardt, L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 12903–12911. doi:10.1002/chem.202001177

and references cited therein. |

| 36. | Ingner, F. J. L.; Giustra, Z. X.; Novosedlik, S.; Orthaber, A.; Gates, P. J.; Dyrager, C.; Pilarski, L. T. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 5648–5655. doi:10.1039/d0gc02263b |

| 37. | Hermann, G. N.; Unruh, M. T.; Jung, S.-H.; Krings, M.; Bolm, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10723–10727. doi:10.1002/anie.201805778 |

| 38. | Cheng, H.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6284–6287. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02973 |

| 39. | Cheng, H.; Hernández, J. G.; Bolm, C. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 1800–1804. doi:10.1002/adsc.201800161 |

| 40. | Hermann, G. N.; Bolm, C. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4592–4596. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b00582 |

| 41. | Hermann, G. N.; Jung, C. L.; Bolm, C. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2520–2523. doi:10.1039/c7gc00499k |

| 42. | Yu, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, C.; Su, W. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 1009–1021. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02951 |

| 43. | Rightmire, N. R.; Hanusa, T. P. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 2352–2362. doi:10.1039/c5dt03866a |

| 44. | Juribašić, M.; Užarević, K.; Gracin, D.; Ćurić, M. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 10287–10290. doi:10.1039/c4cc04423a |

| 45. | Bjelopetrović, A.; Lukin, S.; Halasz, I.; Užarević, K.; Đilović, I.; Barišić, D.; Budimir, A.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10672–10682. doi:10.1002/chem.201802403 |

| 46. | Bjelopetrović, A.; Robić, M.; Halasz, I.; Babić, D.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2019, 38, 4479–4484. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00626 |

| 48. | Ghanbari, N.; Ghafuri, H.; Esmaili Zand, H. R.; Eslami, M. SynOpen 2017, 1, 143–146. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1590959 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 52. | Ma, X.-T.; Tian, S.-K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 337–340. doi:10.1002/adsc.201200902 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 57. | Bjelopetrović, A.; Barišić, D.; Duvnjak, Z.; Džajić, I.; Juribašić Kulcsár, M.; Halasz, I.; Martínez, M.; Budimir, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 17123–17133. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02418 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 55. | Xu, X.-J.; Amuti, A.; Wusiman, A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 5002–5008. doi:10.1002/adsc.202000796 |

| 56. | Caristi, C.; Ferlazzo, A.; Gattuso, M. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1984, 281–285. doi:10.1039/p19840000281 |

| 52. | Ma, X.-T.; Tian, S.-K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 337–340. doi:10.1002/adsc.201200902 |

| 54. | de Figueiredo, R. M.; Suppo, J.-S.; Campagne, J.-M. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12029–12122. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00237 |

| 53. | Kalyani, D.; Dick, A. R.; Anani, W. Q.; Sanford, M. S. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 11483–11498. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.06.075 |

| 51. | Barišić, D.; Halasz, I.; Bjelopetrović, A.; Babić, D.; Ćurić, M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1284–1294. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00698 |

| 52. | Ma, X.-T.; Tian, S.-K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 337–340. doi:10.1002/adsc.201200902 |

© 2022 Barišić et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.