Abstract

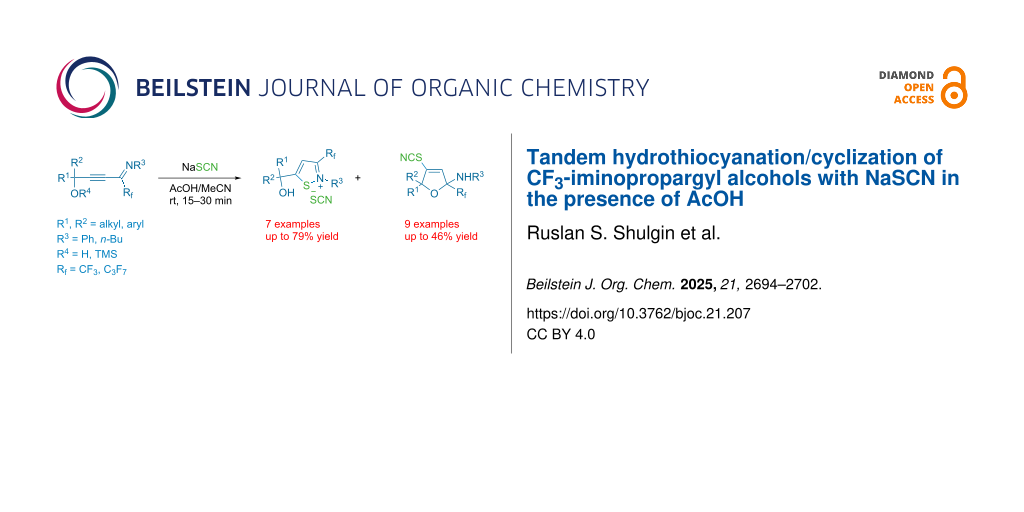

The synthesis of trifluoromethylated isothiazolium thiocyanates and 4-thiocyanato-2,5-dihydrofurans is presented through hydrothiocyanation/cyclization of CF3-iminopropargyl alcohols using NaSCN in AcOH/MeCN. The formation of the two products can be explained by different directions of cyclization of the primary adducts of thiocyanic acid at the triple bond – vinyl thiocyanates. This protocol features simple operating, readily prepared starting materials and occurs under relatively mild conditions.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The hydrofunctionalization of alkynes is one of the most effective and convenient ways of synthesizing polysubstituted alkenes [1-5]. Such reactions can also afford more complex products, provided that the vinyl intermediates formed during the reaction undergo further transformations [6-8]. However, this is mainly possible in the case of functionalized alkynes, where these intramolecular reactions usually involve other functional groups that are contained in the same intermediate.

Among the numerous hydrofunctionalization reactions, hydrothiocyanation has attracted much attention from chemists as it is one of the most expedient and direct methods for the formation of a new C–S bond [9-11]. Thiocyanates represent a valuable class of molecules serving as versatile intermediates [12-15] in the synthesis of a broad range of organosulfur compounds, including thiols, thioethers, disulfides, phosphonothioates, and trifluoromethyl sulfides. Additionally, due to the presence of two electrophilic sites (the sulfur atom and the carbon of the nitrile function), thiocyanates can readily undergo domino-type intramolecular cyclization reactions to form heterocycles. So, if a thiocyanate group is introduced into a molecule bearing a nucleophile in a suitable position, cyclization can readily occur.

In recent years, several methods for the hydrothiocyanation of alkynes bearing functional groups, primarily alkynoates, have been developed. Thus, thiocyano enoates were synthesized via ionic liquid- [16] or lactic acid-catalyzed [17] reactions of alkynoates, KSCN and water under ultrasound conditions as well as by the reactions of alkynoates, KSCN and water using deep eutectic solvents [18]. Reddy and co-workers [19] proposed an approach to thiocyano enones through the hydrothiocyanation of ynones using KSCN in AcOH at 70 °C. They also demonstrated that the adducts of ynones are readily cyclized in situ via a second thiocyanation to form thiazine-2-thiones at a slightly higher temperature and for a longer time. Meanwhile the reaction with ynamides led to decyanative amido cyclization to isothiazolones (Scheme 1). Silver- [20] and gold-catalyzed [21] hydrothiocyanations of haloalkynes with thiocyanate salts in acetic acid to give Z-vinyl thiocyanates were reported. The reaction between alkynic hydrazones and KSCN in AcOH/MeCN delivered N-iminoisothiazolium ylides [22] (Scheme 1). A TFA-mediated cascade cyclization of 2-propynolphenols using KSCN as the thiocyanation source led to the efficient formation of various 4-thiocyanated 2H-chromenes has been developed [23]. 1,3-Oxathiolan-2-ones were obtained by treating 4-hydroxy-2-alkynonitriles with the KSCN/KHSO4 system [24]. In light of the above examples and as part of our ongoing research into the chemistry of functionalized propargyl alcohols [25,26], we decided to use CF3-substituted iminopropargyl alcohols as a starting material for hydrothiocyanation reactions, since the alkynyl imine fragment can undergo a series of different cyclizations due to the conjugated imine and alkyne bonds [27], and the hydroxyalkyl moiety linked to the triple bond can also act as a nucleophilic site. Another attractive feature of these compounds is the presence of the trifluoromethyl group (CF3). The latter serves as a valuable structural motif in various biologically active molecules and materials due to its unique physical, chemical, and biological properties [28-30]. SCN and trifluoromethyl groups have proved to be versatile moieties in the design and development of numerous active pharmaceutical ingredients, agrochemicals, drugs, and organic functional materials. Additionally, CF3-substituted iminopropargyl alcohols can be easily prepared with good yields from commercially available materials in two steps [31,32]. Here, we report for the first time on the hydrothiocyanation of CF3-substituted iminopropargyl alcohols with the MSCN/acid system. In comparison to ynamides [19] and alkynehydrazones [22], whose adducts cyclize with the involvement of nitrogen functional groups at elevated temperatures and extended reaction times, the reaction of CF3-substituted iminopropargyl alcohols occurred at room temperature within 15 min.

Scheme 1: Examples of hydrothiocyanation/cyclization of alkynes.

Scheme 1: Examples of hydrothiocyanation/cyclization of alkynes.

Results and Discussion

We commenced our investigation using CF3-subsituted iminopropargyl alcohol 1a and NaSCN as model substrates. The completion of the reaction was monitored using IR spectroscopy to observe the disappearance of the band at 2219 cm−1 (–C≡C–). It was found that CF3-iminopropargyl alcohol 1a reacted with the NaSCN/acid system to afford a mixture of major isothiazolium thiocyanate 2a and minor 4-thiocyanato-2,5-dihydrofuran 3a. No products were observed in the absence of acid (Et2O/H2O or Me2CO).

Next, an investigation was conducted to determine the most suitable combination of acid and solvent. In a hexane/H2O biphasic system upon vigorous stirring, the reaction of CF3-iminopropargyl alcohol 1a and the NaSCN/KHSO4 system (ratio of 1a/NaSCN/acid 1:2:2) gave products 2a and 3a in 31% and 10% yields, respectively (Table 1, entry 1). Replacing hexane with THF doubled the yield of isothiazolium thiocyanate (Table 1, entry 2). The reaction with chloroacetic acid slightly decreased the yield of 2a (Table 1, entry 4). The use of H2SO4 in THF/H2O gave lower yields of products due to side processes (Table 1, entry 5). However, the change of THF for Me2CO afforded products 2a and 3a in 48% and 13% yields, respectively (Table 1, entry 6). The reaction of 1a with the NaSCN/H2SO4 system in MeCN delivered product 2a in a slightly higher yield (Table 1, entry 8). Acetic acid in a ratio 1a/NaSCN/acid 1:2:2 decreased the yields, as only minor conversion of 1a (20%) was observed (Table 1, entry 9). Increasing the quantity of acetic acid in the reaction mixture improved the product yields, especially for 2,5-dihydrofuran 3a (Table 1, entries 10 and 11). The best yield (76%) of 2a was obtained using acetic acid as co-solvent in a 3:1 (v/v) mixture of MeCN and AcOH (Table 1, entry 12); in this way a total yield of products 2a and 3a of 99% could be obtained. When the reaction was carried out with TFA (ratio of 1a/NaSCN/acid 1:2:2) products 2a and 3a were obtained in 62 and 15%, respectively (Table 1, entry 15). However, a further increase of the TFA amount was detrimental to the yield due to undesirable polymerization side reactions (Table 1, entries 16 and 17). As can be seen from Table 1, the use of strong acids reduces the yields of products due to side processes, whereas more polar solvents increase them. Finally, screening of thiocyanate salts showed that NaSCN was the most suitable source of HSCN for this transformation compared to KSCN and NH4SCN (Table 1, entry 12 vs entries 18 and 19). The optimization of the reaction conditions showed that the best yields were obtained when the reaction was carried out in AcOH/MeCN 1:3 using 2 equiv of NaSCN (Table 1, entry 12). Isothiazolium salt 2a and 2,5-dihydrofuran 3a are easily separable by column chromatography due to their different polarity.

Table 1: Screening of reaction conditions.

|

|

||||||

| Entry | MSCN | Acid | Molar ratio 1a/MSCN/acid | Solvent | Yield of 2a | Yield of 3a |

| 1 | NaSCN | KHSO4 | 1:2:2 | hexane/H2O | 31% | 10% |

| 2 | NaSCN | KHSO4 | 1:2:2 | THF/H2O | 61% | 6% |

| 3 | NaSCN | H3PO4 | 1:2:2 | THF/H2O | 24% | 6% |

| 4 | NaSCN | ClCH2CO2H | 1:2:2 | THF/H2O | 52% | 14% |

| 5 | NaSCN | H2SO4 | 1:2:2 | THF/H2O | 26% | 5% |

| 6 | NaSCN | H2SO4 | 1:2:2 | Me2CO/H2O | 48% | 13% |

| 7 | NaSCN | H2SO4 | 1:1:1 | Me2CO/H2O | 12% | 5% |

| 8 | NaSCN | H2SO4 | 1:2:2 | MeCN | 56% | 6% |

| 9a | NaSCN | AcOH | 1:2:2 | MeCN | 10% | trace |

| 10b | NaSCN | AcOH | 1:2:4 | MeCN | 51% | 27% |

| 11 | NaSCN | AcOH | 1:2:–c | AcOH/hexane | 54% | 30% |

| 12 | NaSCN | AcOH | 1:2:–d | AcOH/MeCN | 76% | 23% |

| 13 | NaSCN | AcOH | 1:3:–d | AcOH/MeCN | 73% | 25% |

| 14 | NaSCN | AcOH | 1:2:–e | AcOH | 54% | 13% |

| 15 | NaSCN | TFA | 1:2:2 | MeCN | 62% | 15% |

| 16 | NaSCN | TFA | 1:2:4 | MeCN | 28% | 6% |

| 17f | NaSCN | TFA | 1:2:–d | TFA/MeCN | – | – |

| 18 | KSCN | AcOH | 1:2:–d | AcOH/MeCN | 71% | 25% |

| 19 | NH4SCN | AcOH | 1:2:–d | AcOH/MeCN | 50% | 18% |

aConversion of 1a was 20%; bconversion of 1a was 90%; cacid was used as a co-solvent in a ratio of 1:6 (AcOH/hexane); dacid was used as a co-solvent in a ratio of 1:3 (AcOH or TFA)/MeCN); eacid was used as a solvent; fstrong resinification of reaction mixture and product not detectable.

Next, we investigated the substrate scope and limitations of the reaction using differently substituted iminopropargyl alcohols (Table 2).

The presence of alkyl substituents in the hydroxy fragment was well tolerated, providing products 2b,c and 3b,c with similar yields (Table 2, entries 1 and 2). The slightly decreased yield observed for product 3c obtained from iminopropargyl alcohol having a cyclohexyl substituent, is probably due to the steric effect (Table 2, entry 2). The more sterically hindered CF3-iminopropargyl alcohols with aromatic substituents 1d (R1 = Ph, R2 = Me) and 1e (R1 = R2 = Ph) were found to be less productive: the reaction required a 2-fold longer time (30 min) and resulted in lower yields of salts 2d,e likely due to side polymerization (Table 2, entries 3 and 4). At the same time, the yields of dihydrofurans 3d,e remained comparable to those of 3a,b. Perhaps the yields of salts 2d,e were affected by steric factors hindering the intramolecular cyclization or their stability under the reaction conditions. Using TMS-protected secondary and primary iminopropargyl alcohols 1f,g (due to their instability) in reaction with the NaSCN/AcOH system failed to afford the corresponding isothiazolium salts 2f,g, and dihydrofurans 3f,g were isolated as the only products (Table 2, entries 5 and 6). In addition, the reaction mixture underwent strong resinification, as primary and secondary propargyl alcohols having electron-withdrawing groups at the triple bond can easily undergo prototropic isomerization to form corresponding unstable allene structures, particularly in acidic conditions. When N-n-Bu CF3-iminopropargyl alcohol 1h was introduced to the reaction, product 2h was obtained in a slightly lower yield (59%) compared to 1a (Table 2, entry 7). Also, C3F7-iminopropargyl alcohol 1i was a suitable substrate giving the desired products 2i and 3i in 75% and 18% yields, respectively (Table 2, entry 8). Clearly, the results show that the substituents in the hydroxy moiety have a significant impact on formation and ratio of the products in contrast to the substituents in the imine fragment.

NMR monitoring of reactions (1a/NaSCN/AcOH or 1g/NaSCN/AcOH in MeCN) did not allow to detect any intermediates even when the temperature was lowered to 0 °C. In the 1H and 19F NMR spectra the signals of products 2a and 3a appeared immediately upon mixing the starting reagents (Figure 1a and b). This indicated that the cyclization occurred almost immediately. Moreover, in the NMR spectra of the 1g/NaSCN/AcOH reaction mixture in MeCN we detected signals assigned to isothiozolium salt 2g (1H NMR: δ 8.30 s (CH), 5.56 s (CH2) ppm, 19F NMR: δ 60.3 ppm), that disappeared by the end of the reaction (Figure 1c and d). Probably, the salts 2f,g are unstable and decompose under the reaction conditions.

![[1860-5397-21-207-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-207-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: 1H and 19F NMR monitoring of 1a/NaSCN/AcOH (a, b) and 1g/NaSCN/AcOH (c, d) reaction mixtures in MeCN.

Figure 1: 1H and 19F NMR monitoring of 1a/NaSCN/AcOH (a, b) and 1g/NaSCN/AcOH (c, d) reaction mixtures in MeC...

The formation of products 2 and 3 can be explained by different directions of cyclization of the primary adduct of thiocyanic acid at the triple bond – vinylthiocyanate A (Scheme 2). Isothiazolium thiocyanate 2 is formed by the attack of the imino nitrogen atom on the sulfur atom and the elimination of the CN anion in the Z-isomer of intermediate A. On the other hand, intramolecular addition of the hydroxy group to the imino group in the E-isomer of adduct A leads to 4-thiocyano-2,5-dihydrofuran 3. Taking into account the NMR monitoring data, it can be assumed that the yield and ratio of products are influenced by the stereoselectivity of the reaction and the stability of salts 2 under reaction conditions.

We also carried out a further derivatization experiment. The product 2a could be oxidized with H2O2 to produce a mixture of 3-hydroxy- and 3-hydroperoxy-2,3-dihydroisothiazole 1,1-dioxides 4 and 5 in a ratio of 4:1, respectively (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3: Oxidation of isothiazolium thiocyanate 2a.

Scheme 3: Oxidation of isothiazolium thiocyanate 2a.

Such cyclic sulfonamides (sultams) are of interest in the field of medicinal chemistry [33,34] and organic synthesis [35]. For example, they have been found to exhibit inhibitory activity against human leukocyte elastase (HLE) [35] and anti-HIV-1-activity [36]. Hydroperoxy sultams can also act as oxidants [37].

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a simple route to trifluoromethylated isothiazolium thiocyanates and 4-thiocyano-2,5-dihydrofurans via the reaction of CF₃-iminopropargyl alcohols with NaSCN/AcOH. The tandem process includes hydrothiocyanation of the triple bond followed by cyclization of the intermediates with the participation of the SCN group and an intramolecular nucleophilic center – imino group or an imino and OH groups. The synthesized compounds are potential drug precursors, synthons, and multipurpose building blocks for fine organic synthesis. We believe that the present method will be of significant interest to synthetic and medicinal chemists due to the operational simplicity, relatively mild conditions and readily prepared starting materials.

Experimental

General information. 1Н, 13С {1H}, and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DPX-400 spectrometer (400.1, 100.6, and 376 MHz, respectively) in CDCl3 and (CD3)2CO using hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDS) as internal reference at 20–25 °C. IR spectra were measured on a Bruker Vertex-70 instrument in thin layer, films or KВr pellets. Microanalyses were performed on a Flash 2000 elemental analyzer. Melting points were determined using a Kofler micro hot stage. Mass spectra were recorded on a GCMSQP5050A spectrometer made by Shimadzu Company. Chromatographic column parameters were as follows: SPBТМ-5, length 60 m, internal diameter 0.25 mm, thickness of stationary phase film 0.25 μm; injector temperature 250 °C; gas carrier helium; flow rate 0.7 mL/min; detector temperature 250 °C; mass analyzer: quadrupole, electron ionization, electron energy: 70 eV, ion source temperature 200 °C; mass range 34–650 Da. The solvent was chloroform or acetone. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh, particle size 0.063–0.200 mm or 230–400 mesh, particle size 0.040–0.063 mm, Merck). Commercially available starting materials were used without further purification. CF3/n-C3F7-substituted iminopropargyl alcohols 1 were prepared according to published methods [31,32]. The structures of synthesized products have been proven by 1H, 13C and 2D (1Н,13С HMBC) NMR, 19F NMR techniques, as well as IR spectra and X-ray diffraction.

Synthesis of isothiazolium thiocyanates 2 and 4-thiocyanato-2,5-dihydrofuran-2-amines 3. Typical procedure. A solution of iminopropargyl alcohol 1 (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv) in 3 mL of acetonitrile was quickly added to a mixture of sodium thiocyanate (1 mmol, 2 equiv) and 1 mL of acetic acid. The reaction was carried out at room temperature and with vigorous stirring for 15 minutes. Next, the solvent was removed and the residue was purified using column chromatography (eluting with diethyl ether/hexane 1:8, then acetone/hexane 2:1 to give products 2 and 3.

Procedure for oxidation of 5-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-2-phenyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)isothiazol-2-ium thiocyanate (2a). Hydrogen peroxide (30%, 0.7 mL) was added dropwise to a solution of 5-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-2-phenyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)isothiazol-2-ium thiocyanate (2a, 0.09 g, 0.26 mmol) in 0.7 mL acetic acid with vigorous stirring. The reaction mixture was heated in a glycerol bath at 80 °C for 10 h. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified by column chromatography (eluting with hexane/acetone 1:1) to obtain the mixture of products 4 and 5.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Full experimental details, characterization data and copies of NMR spectra for all new compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 5.1 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Ananikov, V. P.; Beletskaya, I. P. Alkyne and Alkene Insertion into Metal–Heteroatom and Metal–Hydrogen Bonds: The Key Stages of Hydrofunctionalization Process. In Hydrofunctionalization; Ananikov, V. P.; Tanaka, M., Eds.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 43; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp 1–19. doi:10.1007/3418_2012_54

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hazra, A.; Kephart, J. A.; Velian, A.; Lalic, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 7903–7908. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c03396

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dinda, T. K.; Kabir, S. R.; Mal, P. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 10070–10085. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c00911

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sahoo, M. K.; Kim, D.; Chang, S.; Park, J.-W. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 12777–12784. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c03769

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qing, G. Chem. Synth. 2024, 4, 16. doi:10.20517/cs.2023.38

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chapple, D. E.; Hoffer, M. A.; Boyle, P. D.; Blacquiere, J. M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1532–1542. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.2c00170

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Aghaie, K.; Amiri, K.; Rezaei-Gohar, M.; Rominger, F.; Dar’in, D.; Sapegin, A.; Balalaie, S. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 2661–2664. doi:10.1039/d3cc05724k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, B.-S.; Yang, Y.-X.; Oliveira, J. C. A.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Warratz, S.; Wang, Y.-M.; Li, S.-X.; Wang, X.-C.; Gou, X.-Y.; Liang, Y.-M.; Quan, Z.-J.; Ackermann, L. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101647. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101647

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.; Wu, X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 6443–6484. doi:10.1039/d4ob00804a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yadav, L. D. S.; Patel, R.; Rai, V. K.; Srivastava, V. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 7793–7795. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.09.024

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yadav, L. D. S.; Patel, R.; Srivastava, V. P. Synlett 2008, 1789–1792. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1078549

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Castanheiro, T.; Suffert, J.; Donnard, M.; Gulea, M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 494–505. doi:10.1039/c5cs00532a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Feng, G.; Jin, C. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 39, 287–300. doi:10.6023/cjoc201807016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abonia, R.; Insuasty, D.; Castillo, J.-C.; Laali, K. K. Molecules 2024, 29, 5365. doi:10.3390/molecules29225365

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kindop, V. K.; Bespalov, A. V.; Dotsenko, V. V. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. (N. Y., NY, U. S.) 2024, 60, 345–347. doi:10.1007/s10593-024-03344-w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, C.; Lu, L.-H.; Peng, A.-Z.; Jia, G.-K.; Peng, C.; Cao, Z.; Tang, Z.; He, W.-M.; Xu, X. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 3683–3688. doi:10.1039/c8gc00491a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, C.; Hong, L.; Shu, H.; Zhou, Q.-H.; Wang, Y.; Su, N.; Jiang, S.; Cao, Z.; He, W.-M. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 8798–8803. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b00708

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, M.; Jiang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, Q.; Yu, X. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 130456. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2019.07.014

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dwivedi, V.; Rajesh, M.; Kumar, R.; Kant, R.; Sridhar Reddy, M. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 11060–11063. doi:10.1039/c7cc06081e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Jiang, G.; Zhu, C.; Li, J.; Wu, W.; Jiang, H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 1208–1212. doi:10.1002/adsc.201601142

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zeng, X.; Chen, B.; Lu, Z.; Hammond, G. B.; Xu, B. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 2772–2776. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00728

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, B.-B.; Cao, W.-B.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.-Y.; Ji, S.-J. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 11118–11124. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b01725

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Yang, T.; Song, X.-R.; Li, R.; Jin, F.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.; Yang, R.; Ding, H.; Xiao, Q. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 1248–1253. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.03.070

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dorofeev, I. A.; Mal'kina, A. G.; Trofimov, B. A. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. (N. Y., NY, U. S.) 2001, 37, 903–906. doi:10.1023/a:1012416028013

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shulgin, R. S.; Volostnykh, O. G.; Stepanov, A. V.; Ushakov, I. A.; Shemyakina, O. A. J. Fluorine Chem. 2023, 270, 110173. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2023.110173

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shulgin, R. S.; Volostnykh, O. G.; Stepanov, A. V.; Ushakov, I. A.; Shemyakina, O. A. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 2728–2734. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.4c02959

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shimizu, M.; Hachiya, I.; Mizota, I. Chem. Commun. 2009, 874–889. doi:10.1039/b814930e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Abula, A.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Peng, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, W.; Aisa, H. A. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 6242–6250. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00898

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Gu, K.; Zhao, J.; Ning, J.; Perepichka, D. F.; Loo, Y.-L.; Meng, H. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 12149–12155. doi:10.1039/d0ta00098a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alamro, F. S.; Ahmed, H. A.; El-Atawy, M. A.; Khushaim, M. S.; Bedowr, N. S.; AL-Faze, R.; Al-Kadhi, N. S. Materials 2023, 16, 4304. doi:10.3390/ma16124304

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Xie, H.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y. J. Fluorine Chem. 2011, 132, 196–201. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2011.01.003

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Schneider, T.; Seitz, B.; Schiwek, M.; Maas, G. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 235, 109567. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109567

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chong, Y. K.; Ong, Y. S.; Yeong, K. Y. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 1798–1827. doi:10.1039/d3md00653k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Park, H.; Raikar, S. S.; Kim, Y.; Chae, C. H.; Cho, Y.-H.; Kim, P. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2025, 46, 48–56. doi:10.1002/bkcs.12921

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Debnath, S.; Mondal, S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 933–956. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201701491

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Eilfeld, A.; González Tanarro, C. M.; Frizler, M.; Sieler, J.; Schulze, B.; Gütschow, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 8127–8135. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.049

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Makota, O.; Wolf, J.; Trach, Y.; Schulze, B. Appl. Catal., A 2007, 323, 174–180. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2007.02.013

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Ananikov, V. P.; Beletskaya, I. P. Alkyne and Alkene Insertion into Metal–Heteroatom and Metal–Hydrogen Bonds: The Key Stages of Hydrofunctionalization Process. In Hydrofunctionalization; Ananikov, V. P.; Tanaka, M., Eds.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Vol. 43; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp 1–19. doi:10.1007/3418_2012_54 |

| 2. | Hazra, A.; Kephart, J. A.; Velian, A.; Lalic, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 7903–7908. doi:10.1021/jacs.1c03396 |

| 3. | Dinda, T. K.; Kabir, S. R.; Mal, P. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 10070–10085. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c00911 |

| 4. | Sahoo, M. K.; Kim, D.; Chang, S.; Park, J.-W. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 12777–12784. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c03769 |

| 5. | Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qing, G. Chem. Synth. 2024, 4, 16. doi:10.20517/cs.2023.38 |

| 16. | Wu, C.; Lu, L.-H.; Peng, A.-Z.; Jia, G.-K.; Peng, C.; Cao, Z.; Tang, Z.; He, W.-M.; Xu, X. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 3683–3688. doi:10.1039/c8gc00491a |

| 27. | Shimizu, M.; Hachiya, I.; Mizota, I. Chem. Commun. 2009, 874–889. doi:10.1039/b814930e |

| 12. | Castanheiro, T.; Suffert, J.; Donnard, M.; Gulea, M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 494–505. doi:10.1039/c5cs00532a |

| 13. | Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Feng, G.; Jin, C. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 39, 287–300. doi:10.6023/cjoc201807016 |

| 14. | Abonia, R.; Insuasty, D.; Castillo, J.-C.; Laali, K. K. Molecules 2024, 29, 5365. doi:10.3390/molecules29225365 |

| 15. | Kindop, V. K.; Bespalov, A. V.; Dotsenko, V. V. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. (N. Y., NY, U. S.) 2024, 60, 345–347. doi:10.1007/s10593-024-03344-w |

| 28. | Abula, A.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Peng, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, W.; Aisa, H. A. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 6242–6250. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00898 |

| 29. | Yao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Gu, K.; Zhao, J.; Ning, J.; Perepichka, D. F.; Loo, Y.-L.; Meng, H. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 12149–12155. doi:10.1039/d0ta00098a |

| 30. | Alamro, F. S.; Ahmed, H. A.; El-Atawy, M. A.; Khushaim, M. S.; Bedowr, N. S.; AL-Faze, R.; Al-Kadhi, N. S. Materials 2023, 16, 4304. doi:10.3390/ma16124304 |

| 9. | Xu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.; Wu, X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 6443–6484. doi:10.1039/d4ob00804a |

| 10. | Yadav, L. D. S.; Patel, R.; Rai, V. K.; Srivastava, V. P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 7793–7795. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.09.024 |

| 11. | Yadav, L. D. S.; Patel, R.; Srivastava, V. P. Synlett 2008, 1789–1792. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1078549 |

| 24. | Dorofeev, I. A.; Mal'kina, A. G.; Trofimov, B. A. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. (N. Y., NY, U. S.) 2001, 37, 903–906. doi:10.1023/a:1012416028013 |

| 6. | Chapple, D. E.; Hoffer, M. A.; Boyle, P. D.; Blacquiere, J. M. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1532–1542. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.2c00170 |

| 7. | Aghaie, K.; Amiri, K.; Rezaei-Gohar, M.; Rominger, F.; Dar’in, D.; Sapegin, A.; Balalaie, S. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 2661–2664. doi:10.1039/d3cc05724k |

| 8. | Zhang, B.-S.; Yang, Y.-X.; Oliveira, J. C. A.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Warratz, S.; Wang, Y.-M.; Li, S.-X.; Wang, X.-C.; Gou, X.-Y.; Liang, Y.-M.; Quan, Z.-J.; Ackermann, L. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101647. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101647 |

| 25. | Shulgin, R. S.; Volostnykh, O. G.; Stepanov, A. V.; Ushakov, I. A.; Shemyakina, O. A. J. Fluorine Chem. 2023, 270, 110173. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2023.110173 |

| 26. | Shulgin, R. S.; Volostnykh, O. G.; Stepanov, A. V.; Ushakov, I. A.; Shemyakina, O. A. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 2728–2734. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.4c02959 |

| 20. | Jiang, G.; Zhu, C.; Li, J.; Wu, W.; Jiang, H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 1208–1212. doi:10.1002/adsc.201601142 |

| 22. | Liu, B.-B.; Cao, W.-B.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.-Y.; Ji, S.-J. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 11118–11124. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b01725 |

| 19. | Dwivedi, V.; Rajesh, M.; Kumar, R.; Kant, R.; Sridhar Reddy, M. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 11060–11063. doi:10.1039/c7cc06081e |

| 23. | Yang, T.; Song, X.-R.; Li, R.; Jin, F.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.; Yang, R.; Ding, H.; Xiao, Q. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 1248–1253. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.03.070 |

| 18. | Sun, M.; Jiang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, Q.; Yu, X. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 130456. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2019.07.014 |

| 17. | Wu, C.; Hong, L.; Shu, H.; Zhou, Q.-H.; Wang, Y.; Su, N.; Jiang, S.; Cao, Z.; He, W.-M. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 8798–8803. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b00708 |

| 21. | Zeng, X.; Chen, B.; Lu, Z.; Hammond, G. B.; Xu, B. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 2772–2776. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00728 |

| 22. | Liu, B.-B.; Cao, W.-B.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.-Y.; Ji, S.-J. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 11118–11124. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b01725 |

| 31. | Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Xie, H.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y. J. Fluorine Chem. 2011, 132, 196–201. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2011.01.003 |

| 32. | Schneider, T.; Seitz, B.; Schiwek, M.; Maas, G. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 235, 109567. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109567 |

| 19. | Dwivedi, V.; Rajesh, M.; Kumar, R.; Kant, R.; Sridhar Reddy, M. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 11060–11063. doi:10.1039/c7cc06081e |

| 37. | Makota, O.; Wolf, J.; Trach, Y.; Schulze, B. Appl. Catal., A 2007, 323, 174–180. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2007.02.013 |

| 31. | Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Xie, H.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y. J. Fluorine Chem. 2011, 132, 196–201. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2011.01.003 |

| 32. | Schneider, T.; Seitz, B.; Schiwek, M.; Maas, G. J. Fluorine Chem. 2020, 235, 109567. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109567 |

| 35. | Debnath, S.; Mondal, S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 933–956. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201701491 |

| 36. | Eilfeld, A.; González Tanarro, C. M.; Frizler, M.; Sieler, J.; Schulze, B.; Gütschow, M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 8127–8135. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.049 |

| 33. | Chong, Y. K.; Ong, Y. S.; Yeong, K. Y. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 1798–1827. doi:10.1039/d3md00653k |

| 34. | Park, H.; Raikar, S. S.; Kim, Y.; Chae, C. H.; Cho, Y.-H.; Kim, P. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2025, 46, 48–56. doi:10.1002/bkcs.12921 |

| 35. | Debnath, S.; Mondal, S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 933–956. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201701491 |

© 2025 Shulgin et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.