Abstract

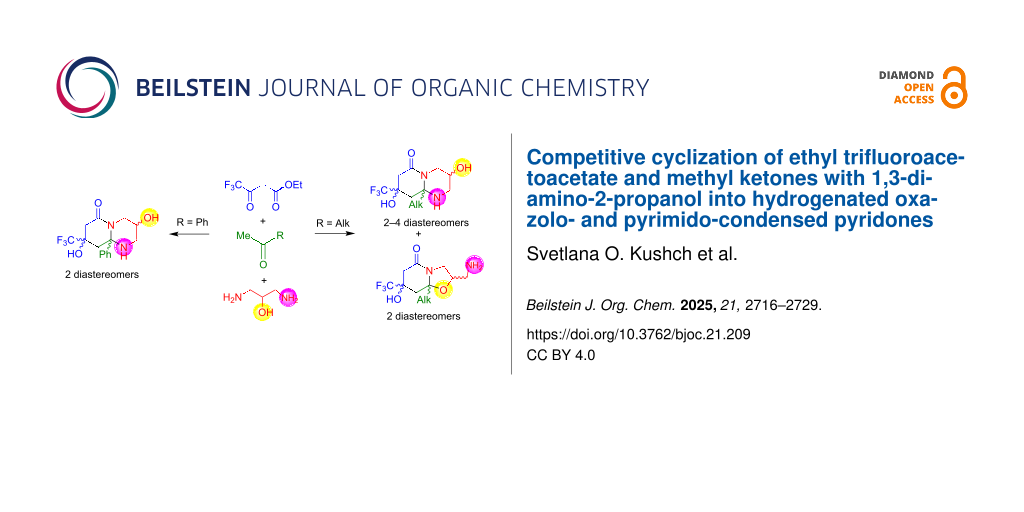

The use of 1,3-diamino-2-propanol with competitive N- and O-nucleophilic centers in a three-component cyclization with ethyl 4,4,4-trifluoroacetoacetate and methyl ketones enables the synthesis to be carried out for octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-ones and hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-ones, the preferential formation of which depends on the substituent in the methyl ketone component. Dual acid–base catalysis of the reactions with alkyl methyl ketones increases the regioselectivity in the synthesis of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones. The cyclization with acetophenone is characterized by the regiospecific generation of these bicycles. The presence of three chiral centers in the synthesized bicycles, depending on the alkyl substituent, causes the formation of two to four diastereomers, the structure of which has been determined with 1H, 19F, 13C, 2D 1H-13C HSQC/HMBC, 1H-1H COSY/NOESY NMR and X-ray diffraction analysis.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The modern strategy of organic synthesis is aimed at conforming to the "green chemistry" principles based on PASE (pot, atom, step, economic) methods. These principles serve as the foundation for multicomponent processes that allow various structurally complex molecules to be obtained in one stage using commercially available reagents [1-3].

Their ambident properties make 3-oxo esters convenient reagents for the use in multicomponent syntheses, with the Hantzsch [4,5] and Biginelli [6-8] reactions being the best known. In the transformations, 3-oxo esters are cyclized with aldehydes and ammonia (monoamines) or urea to yield a certain type of products only: pyridines and pyrimidines; and formation of the products proceeds with the involvement of an acyl fragment and the meso-position of an oxo ester component [9]. Although the introduction of 2-aminoazoles into the Biginelli reaction allows azolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines [10-16] to be synthesized, in general, the range of products obtained in these syntheses is predictable and limited.

Ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate and its polyfluoroalkyl-containing analogues are also used widely as starting substrates in multicomponent syntheses [17-19]; at the same time, they often show extraordinary reactivity. For example, the introduction of polyfluoroalkyl-3-oxo esters into the aforementioned Hantzsch and Biginelli reactions leads to the hydrated heterocycles, which can provide insight into the mechanistic aspects of these transformations.

Our team has discovered a new multicomponent synthesis that is based on autocatalyzed reactions of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate and other polyfluoroalkyl-3-oxo esters with α-methylenecarbonyl compounds and amines [9]. This approach is appropriate only for 3-polyfluoroalkyl-3-oxo esters containing an activated carbonyl group capable of adding α-methylene ketones. It is characterized by the cyclization at the 1,3-dicarbonyl fragment of 3-oxo ester and offers a possibility of using a variety of nucleophilic agents to form hydrogenated diastereomeric hetero- and carbocycles. To date, we have proposed new protocols for the synthesis of 2-pyridones [20], imidazo[1,2-a]pyridones and pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones [21-24], pyrido[2,1-b]oxazinones and oxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones [25] using ammonia, 1,2- and 1,3-diamines or 1,2- and 1,3-amino alcohols, respectively. The introduction of cycloketones has resulted in the same types of heterocyclic systems, yet they are now carboannelated, which are synthetic analogues of alkaloids [26]. Moreover, it has been shown that acetaldehyde is capable of reacting in a similar manner with ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate and ethylenediamine [27] as well as with 2-(aminomethyl)aniline and 1,3-diaminopropane [28]. In addition, we have found another route for the three-component cyclization of 3-polyfluoroalkyl-3-oxo esters with α-methylene ketones involving mono- and dialkylamines, leading to 5-polyfluoroalkylaminocyclohexen-2-ones [29]. In general, the developed approach allows pyridone derivatives to be generated in various environments of condensed carbo- and heterocyclic structures. Among the synthesized pyridone derivatives we have found analgesic [20,26], antibacterial [20] and antifungal [20] agents, which show practical promise for the three-component approach we have proposed.

The importance of trifluoromethyl-containing pyridine and piperidine systems is well known for both medical and agrochemical applications [30]. Thus, many medicinal agents have such fragments, for example, the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor doravirine [31], calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonist ubrogepant [32], dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor gemigliptin [33]. The trifluoromethyl pyridine framework is also widely used in the development of plant protection products [34], including the fungicides fluopicolide [35], fluopyram [36], and the nematicide fluazaindolisine [37] (Figure 1). The trifluoromethyl piperidine backbone is part of the structure of anticancer [38] and antirheumatic [39] agents.

Figure 1: Structures of bioactive molecules with trifluoromethylpyridine and piperidine frameworks.

Figure 1: Structures of bioactive molecules with trifluoromethylpyridine and piperidine frameworks.

The fluorine-containing pyridines and their heteroannelated derivatives are known to exhibit a high biological potential, on the one hand, owing to the fact that the pyridine framework is widespread among natural compounds [40,41], and, on the other hand, because of the unique properties of fluorine [42-45].

In this work, 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol (3) has for the first time been introduced into the reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1) with methyl ketones 2. This reagent has alternative N- and O-reactive centers and thus can react as an N,N- or N,O-dinucleophile, generating in a single synthesis trifluoromethyl octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-ones or hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-ones, or both that contain an additional functional group, the presence of which should affect their diastereomeric structure.

We have found only one work describing the use of 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol to form heterocycles, where it is reported to react with chloroacetaldehyde and carbon dioxide as an N,N-dinucleophile only, giving hexahydro[1,3]oxazolo[3,4-a]pyrimidin-6-one [46]. Here, we have made research efforts to explore the possibility of using 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol for the synthesis of pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidine and oxazolo[3,2-a]pyridine. Our research interest is caused by the potential biological activity of the compounds, since there are antileishmanial [47], antibacterial [48], antimalarial agents [49] as well as COX-2 [50] and FGFR [51] inhibitors found among them. Moreover, various drugs (antipsychotic risperidone [52] and pirenperone [53], antiallergic ramastine [54]) have been obtained on the basis of pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidine; and compositions of antitumor antibiotics of the kigamycin family include the oxazolo[3,2-a]pyridine skeleton [55,56].

To obtain oxazolopyridones containing trifluoromethyl substituents, the syntheses have been proposed, which are based on the intramolecular cyclization of 1-phenyl-2-(4-(trifluoromethyl)piperidin-1-yl)ethane-1,2-dione [57], or 4-(4-phenyl-2-(trifluoromethyl)oxazolidin-2-yl)butanoic acid under acidic conditions [58], and condensation of 6,6,6-trifluoro-5-oxohexanoic acid with (S)-(+)-phenylglycine [59]. The data on the multicomponent synthesis of fluoroalkyl-containing pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidines are limited to our studies only [21-24]; however, there are various one- [60] and two-component [61-65] approaches to obtaining trifluoromethyl-containing pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidines available in literature.

Results and Discussion

We began our research by searching for optimal conditions for the reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1) and acetone (2a) with 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol (3) (Scheme 1). The selection of conditions is necessary, because alternative octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 4 and hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-one 5 can be formed due to the presence of three nucleophilic centers in 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol (3), and because there is a need to increase diastereoselectivity of the cyclization process. Table 1 presents the optimization steps for the reaction conditions at various solvents and temperature.

Scheme 1: The reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1), acetone (2a) and 1,3- diaminopropan-2-ol (3).

Scheme 1: The reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1), acetone (2a) and 1,3- diaminopropan-2-ol (3).

Table 1: Optimization of the reaction conditions for ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1), acetone (2a) and 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol (3).

| entry | conditionsa | Т, °С | time | composition of the reaction mixture [%]b | |||||||

| 1c | 4att | 4atc | 4acc | 4act | 5atc | 5att | othersd | ||||

| 1 | 1,4-dioxane | 25 | 4 d | 2 | 27 | 17 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 16 |

| 2 | MeCN | 25 | 4 d | 3 | 33 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 20 |

| 3 | THF | 25 | 4 d | 12 | 25 | 17 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 26 |

| 4 | EtOH | 25 | 4 d | 8 | 20 | 13 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 22 |

| 5* | 1,4-dioxane | 60 | 24 h | – | 31 | 20 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 11 | 17 |

| 6 | 1,4-dioxanee | 60 | 5 h | 2 | 24 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 23 |

| 7 | 1,4-dioxanef | 60 | 24 h | – | 10 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 13 | 42 |

| 8 | 1,4-dioxaneg | 60 | 24 h | – | 4 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 11 | 61 |

| 9 | 1,4-dioxaneh | 60 | 24 h | – | 27 | 18 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 14 |

| 10** | 1,4-dioxanei | 60 | 24 h | – | 22 | 17 | 28 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 13 |

| 11 | DCEe,j | 60 | 10 h | – | 8 | 4 | 9 | 14 | 5 | 4 | 56 |

aReactions were carried out with 1 (1 mmol), 2a (1 mmol) and 3 (1 mmol) in 2 mL of the solvent. bDetermined by 19F NMR analysis of the mixture: 4att (δF 79.52 ppm), 4atc (δF 79.61 ppm), 4acc (δF 79.91 ppm), 4act (δF 80.02 ppm), 5atc (δF 79.66 ppm), 5att (δF 79.74 ppm). cUnreacted residue of ester 1. dUnidentified products. eThe reaction was performed in a closed vial in a CEM Discover microwave synthesizer, MW 50 W. f1 mmol of AcOH was used. g2 mmol of AcOH was used. h1 mmol of Et3N was used. i2 mmol of AcOH and Et3N were used. j0.2 mmol of DMAP was used.

The reaction course was monitored by TLC and 19F NMR spectroscopy. In all the four solvents used, both types of products were formed: octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one as four diastereomers 4att (δF 79.52 ppm), 4atc (δF 79.61 ppm), 4acc (δF 79.91 ppm), 4act (δF 80.02 ppm); and hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-one as two diastereomers 5atc (δF 79.66 ppm) and 5att (δF 79.74 ppm) (Table 1, entries 1–4). The synthesis in 1,4-dioxane resulted in the highest conversion and the least amount of by-products, but the reaction proceeded slowly over four days. To speed up the process, the synthesis in dioxane was carried out by heating at 60 °C (Table 1, entry 5) in a microwave (MW) reactor (Table 1, entry 6). It turned out that after 24 hours of heating the complete conversion of oxo ester 1 occurred and the overall yield increased to 83% (Table 1, entry 5), whereas the use of MW reduced the reaction time down to five hours (Table 1, entry 6), but the contents of by-products were observed to increase to 23%.

Under all conditions used, the predominant formation of the trans,trans-diastereomeric form of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 4att was observed (with the maximum amount of 33% in polar MeCN). Heating in dioxane affected the diastereomeric composition of the products, increasing the content of the trans,cis-form 4atc to 20%.

The use of 1,4-dioxane with acetic acid catalysis at different molar ratios (Table 1, entries 7, 8) led to the formation of a large fraction of unidentified by-products (42–61%), whereas the base catalysis with triethylamine in 1,4-dioxane (Table 1, entry 9) did not affect the reaction course significantly. The use of conditions with catalysis by a combination of Bronsted acid and base (acetic acid, Et3N) contributed to a shift in the reaction selectivity towards octahydropyridopyrimidinones 4 (overall yield 71%) (Table 1, entry 10), with the formation of the cis,cis-bicycle 4acc as the predominant product (28%), while the proportion of hexahydrooxazolopyridones 5 was minimal (10%) compared to all other conditions.

The highest content of hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-one 5a was observed at room temperature in 1,4-dioxane (diastereomer 5atc, 10%) and 1,4-dioxane with acetic acid at 60 °C (diastereomer 5att, 13%). The attempts were made to increase their proportion further by using the conditions (DCE, 4-DMAP (20%), MW, 60 °C) (Table 1, entry 11); those conditions have proved effective for the synthesis of octahydrocyclopenta[b]oxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-ones in the reactions of 3-oxo ester 1 and cycloketones with amino alcohols [26]. However, these attempts turned out to be unsuccessful because of the increased occurrence of side processes (56%); however, an increase in the proportion of the cis,trans-octahydropyridopyrimidinone 4act to 14% was observed.

We succeeded in isolating all six products 4 and 5 from the reaction of ester 1, acetone (2a), amine 3 in dioxane (Scheme 1). Octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4act and 4att, which were formed in larger quantities, were the first to be isolated: the bicycle 4act precipitated from the reaction, which allowed it to be easily isolated and purified by crystallization from MeCN. Diastereomer 4att was obtained from the filtrate also by crystallization from MeCN. Column chromatography allowed us to isolate octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4atc, 4acc in an individual form, and hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones 5atc and 5att in a mixture at a ratio of 11:9.

To carry out similar reactions of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1) and 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol (3) with methyl ketones 2b–d, the two most productive conditions were selected: heating at 60 °C in 1,4-dioxane, either without catalysis or using triethylamine–acetic acid as a bifunctional catalyst (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Three-component reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1), alkyl methyl ketones 2b,c and 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol (3). Reaction conditions: i. 1,4-dioxane, 60 °C; ii. 1,4-dioxane, AcOH, Et3N, 60 °C.

Scheme 2: Three-component reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1), alkyl methyl ketones 2b,c and 1,3-diam...

The reactions with alkyl methyl ketones 2b,c in 1,4-dioxane without catalysis led to the formation of a mixture of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4b,c and hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones 5b,c, but with a predominance of the latter and an another diastereomeric composition of the products. In the reaction with 2-butanone (2b), three diastereomers of 4b and two diastereomers of 5b were formed. The bicycles 4bct (δF 80.09 ppm), 5btc (δF 79.65 ppm), 5btt (δF 79.73 ppm) were isolated in an individual form, and the octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4bcс (δF 80.00 ppm) and 4btс (δF 79.50 ppm) were obtained in a mixture at a ratio of 4:1 (Scheme 2). The transformations with 2-hexanone (2c) led to the formation of two diastereomers of 4cct (δF 80.09 ppm) and 4ccc (δF 80.00 ppm), two diastereomers of 5ctc (δF 79.65 ppm) and 5ctt (δF 79.74 ppm). All products were individually isolated by column chromatography.

Carrying out these syntheses in 1,4-dioxane in the presence of acetic acid and triethylamine increased the selectivity for the formation of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4 in the reactions with alkyl methyl ketones 2b,c (Scheme 2), similar to the transformations with acetone 2a (Scheme 1). The conversion and the preparative yields of products 4b,c and 5b,c are given in Table 2.

Table 2: The conversion and the preparative yields of products 4b,c and 5b,c.

| products | δF, ppm | 1,4-dioxane, 60 °C | 1,4-dioxane, AcOH, Et3N, 60 °C | ||

| 19F NMR data, % | yield, % | 19F NMR data, % | yield, % | ||

| R = Et | |||||

| 4bcc | 80.00 | 21 | 21 (4:1) | 36 | 32 (4:1) |

| 4btc | 79.50 | 6 | 9 | ||

| 4bct | 80.09 | 17 | 13 | 26 | 22 |

| 5btc | 79.65 | 21 | 16 | 6 | – |

| 5btt | 79.73 | 22 | 18 | 9 | – |

| R = Bu | |||||

| 4ccc | 80.00 | 14 | 8 | 25 | 21 |

| 4cct | 80.09 | 18 | 13 | 21 | 18 |

| 5ctc | 79.65 | 23 | 17 | 4 | – |

| 5ctt | 79.74 | 25 | 19 | 7 | 3 |

The regioselectivity is the main feature of the reaction of ester 1 and diaminopropanol (3) with acetophenone (2d), because in this case only octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinone is obtained in the form of cis,trans- and cis,cis-diastereomers 4dct (δF 80.03 ppm) and 4dcc (δF 79.94 ppm). Carrying out the reaction under AcOH/Et3N catalysis allowed the ratio of isomers to be changed, increasing the amount of diastereomer 4dcc, which was minor when heated in 1,4-dioxane (Scheme 3, Table 3).

Scheme 3: Three-component reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1), acetophenone (2d) and 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol (3). Reaction conditions: i. 1,4-dioxane, 60 °C; ii. 1,4-dioxane, AcOH, Et3N, 60 °C.

Scheme 3: Three-component reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate (1), acetophenone (2d) and 1,3-diaminopropa...

Previously, we proposed and experimentally confirmed an aldol mechanism underlying the three-component cyclization of polyfluoroalkyl-3-oxo esters with α-methylene ketones and amines in piperidone derivatives. According to this mechanism, the key intermediate is aldol A, which is formed from 3-oxo ester 1 and methyl ketone 2 under the catalysis of amine 3 [24,25,29]. Therefore, we suggest that the formation of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4 and hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones 5 proceeds via the initial formation of aldol A, which then reacts at the acyl moiety with the amino group of diamino alcohol 3 to generate a three-component intermediate B (Scheme 4). The latter undergoes intramolecular cyclization involving the C=N bond in two equally probable directions: by adding a free amino group to form a hexahydropyrimidine ring of intermediate C (path a), or by adding an OH group to generate an oxazolidine ring of intermediate D (path b). The subsequent intramolecular cyclization of intermediates C and D involving a secondary NH group and an ester substituent yields the bicycles 4 and 5, respectively (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4: The proposed mechanism of three-component cyclization of 3-oxo ester 1, methyl ketones 2a–d and 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol (3).

Scheme 4: The proposed mechanism of three-component cyclization of 3-oxo ester 1, methyl ketones 2a–d and 1,3...

In the reactions with acetophenone (2d), only path a is realized leading to octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4d, whereas in the syntheses with alkyl methyl ketones 2a–c, both paths proceed. At the same time, in the reactions with acetone (2a), path a predominates; and in the reactions with 2-butanone (2b) and 2-hexanone (2c), the ratio of the resulting bicycles 4b,c and 5b,c is approximately the same, with a slight predominance of 5b,c that are formed by path b (Scheme 4). Apparently, in the intermediate B, which was obtained from acetophenone (2d), the phenyl substituent exerts a strong positive mesomeric effect on the imine reaction center. This makes the center softer, which favors the interaction with the amino group to generate the hexahydropyrimidine intermediate C. The methyl, ethyl and butyl substituents of intermediate B have a positive inductive effect, which increases with the lengthening of the alkyl chain. As a result, the cyclization becomes competitive in both directions, but with a predominance of path b as the alkyl chain lengthens [66].

The use of acetic acid and triethylamine results in the dominance of path a in all of the reactions. Most likely, the acid catalyzes the imine center in the intermediate B, which becomes softer for attack by the amino group.

It is worth noting that the diastereoselectivity of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones formation 4a–c in the reactions with alkyl methyl ketones 2a–c is also affected by the length of the alkyl chain, with the number of diastereomers decreasing as the alkyl chain lengthens. Thus, in cyclization with acetone (2a), four diastereomers 4a are formed, with 2-butanone (2b) – three isomers 4b, and with 2-hexanone (2c) – two ones 4c. Also, two isomers 4d are formed in the reaction with acetophenone (2d). This is consistent with our earlier data [24], which showed an increase in the diastereoselectivity in synthesis of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones in the three-component reaction of ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate and 1,3-diaminopropane with methyl ketones with an increase in the volume of substituent in the ketone component.

Unlike the octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4a–c, the hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones 5a–c are formed as two diastereomers regardless of the conditions, which may be due to the greater conformational rigidity of the five-membered oxazolidine cycle compared to the six-membered hexahydropyrimidine one.

The structure of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4a–d and hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones 5a–c was determined by IR, 1H, 19F, 13C NMR spectroscopy, two-dimensional NMR experiments, and X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD).

The IR spectra of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4a–d are characterized by reduced vibrational frequencies of the carbonyl function (ν 1633–1593 cm−1) and N–H, O–H groups (ν 3435–3126 cm−1), which indicates their participation in the hydrogen bond formation [67]. On the other hand, the IR spectra of hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones 5a–c contain intense absorption bands of the C=O function at ν 1652–1628 cm−1 and NH2 groups at ν 3376–3272 cm−1.

The structures of the obtained heterocycles 4 and 5 contain three stereocenters, so one could expect the formation of up to 8 stereoisomers in each case. Analysis of the 19F NMR spectra showed that from two to four diastereomers of octahydropyridopyrimidinones 4 and two diastereomers of hexahydrooxazolopyridones 5 were formed in the transformations under study. The stereoconfiguration of octahydropyridopyrimidinones 4аcc, 4аct, 4аtt, 4аtc, 4dct and hexahydrooxazolopyridones 5ctc, 5ctt was determined using XRD and it served as the basis for assigning the configuration of other diastereomers (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Analysis of the XRD results shows that the formation of bicyclic compounds are formed with two types of ring fusion: trans- and cis-type, similar to the structure of decalin [68].

![[1860-5397-21-209-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-209-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: ORTEP view of compounds 4асc (a, CCDC: 2479553), 4аct (b, CCDC: 2479554), 4аtt (c, CCDC: 2479555), 4аtc (d, CCDC: 2479556), and 4dct (e, CCDC: 2479557) showing with the thermal ellipsoids at 50% probability.

Figure 2: ORTEP view of compounds 4асc (a, CCDC: 2479553), 4аct (b, CCDC: 2479554), 4аtt (c, CCDC: 2479555), ...

![[1860-5397-21-209-3]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-209-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: ORTEP view of compound 5ctc (a, CCDC: 2479558), 5ctt (b, CCDC: 2479559) showing with the thermal ellipsoids at 50% probability.

Figure 3: ORTEP view of compound 5ctc (a, CCDC: 2479558), 5ctt (b, CCDC: 2479559) showing with the thermal el...

In all studied structures 4аcc, 4аct, 4аtt, 4аtc, 4dct, 5ctc, 5ctt (Figure 2 and Figure 3), the piperidone ring has a half-chair conformation in which the pseudo-equatorially located trifluoromethyl group is a conformational anchor. The five atoms of the six-membered piperidone ring are coplanar, and the trifluoromethyl-substituted carbon atom С(8) is significantly deviated by more than 0.5 Å above or below the ring plane. Accordingly, the adjacent hydroxy substituent has a pseudo-axial position. The hexahydropyrimidine ring in bicycles 4аcc, 4аct, 4аtt, 4аtc, 4dct has a chair conformation, and the oxazolidine ring in heterocycles 5ctc, 5ctt has an envelope conformation, with a deviation of the oxygen atoms O(1) by 0.5 Å for 5ctc and nitrogen atoms N(1) by 0.4 Å for 5ctt.

In trans-junction, bicycles 4att, 4atc (Figure 2c,d) have a flattened fixed skeleton with a dihedral angle of 24.8–27.3° (see Table S9, in Supporting Information File 1), in which the substituent R at the bridgehead carbon atom can occupy only an axial position with respect to both cycles. On the other hand, the CF3 group is a conformational anchor and always occupies a pseudo-equatorial position, which is why it leads to the trans-configuration of the piperidone cycle. In the cis-junction, the conformation of octahydropyridopyrimidinones 4acc, 4act, and 4dct (Figure 2a,b,e) is more curved, with a larger dihedral angle of 47.8–53.9°, where both the substituent R at the bridgehead carbon atom and the CF3 group are located in pseudo-equatorial positions, and that determines the cis-configuration of the piperidone ring. At the same time, in relation to the hexahydropyrimidine ring, the bridgehead substituent R occupies a pseudo-axial position. The relative configuration of the hexahydropyrimidine ring in compounds 4 is determined by the pseudo-axial (trans) or equatorial (cis) position of the OH group.

The crystal packing of single crystals 4att, 4atc, 4acc, 4act, 4dct is ordered by intermolecular hydrogen bonds linking O–H groups and heteroatoms O/N of neighboring molecules (see Table S8 in Supporting Information File 1); N–H groups of the hexahydropyrimidine ring and a carbonyl fragment of the neighboring molecule also participate in the pattern of 4att crystal packing. In addition, in the cis-configuration of the pseudo-axially located NH and OH groups in the structures 4acc, 4act and 4dct, a strong intramolecular N–H···O hydrogen bond is observed.

The crystal packing of hexahydrooxazolopyridone 5ctt is ordered by intermolecular hydrogen bonds of the NH2 group with the hydroxy and carbonyl functions of two other molecules (Figure 3b). The OH substituent of the piperidone ring is in the trans-configuration relative to O(4) atom. In the oxazolidine ring, the CH2NH2 group occupies a pseudo-equatorial position and is in the trans-position toward the Bu group. The single crystal structure of the bicycle 5ctc is ordered by intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the hydroxy group and the amino group as well as between the amino group and fluorine of the CF3 substituent of the neighboring molecule (Figure 3a). The hydroxy substituent of the piperidone ring is in cis-configuration relative to O(4) atom. In the oxazolidine ring, the CH2NH2 group occupies a pseudo-equatorial position and is placed in the cis-position toward the Bu group.

The stereochemical features derived from the XRD data on single crystal 4a–d and 5a–c are in excellent agreement with the results of 1D and 2D NMR studies, enabling us to extend these structural assignments to other synthesized bicycles. The complete assignment of signals in 1H and 13C NMR spectra was performed using two-dimensional 1H-1H COSY, NOESY and 1H-13C HSQC, HMBC experiments. The relative configuration was established based on the analysis of spin–spin coupling constants 3JH,H and 4JH,H as well as on a set of NOE-correlations.

Equatorial or pseudo-equatorial protons of the methylene groups in compounds 4 and 5 were identified by the long-range coupling constants 4JH,H = 2.6–3.6 Hz, which is typical for the W-arrangement of atoms. The trans-configuration of the piperidone ring is confirmed by NOE correlations between C(8)OH and the protons of the R substituent located in the 1,3-diaxial positions. The cis-configuration of the piperidone ring is characterized by NOE correlations between the protons of the pseudo-equatorial substituent R and the axial proton at C(9). The cis-configuration of the pyrimidine ring is proven by the cross-peaks in the NOESY spectrum of the protons of axial substituent R and the equatorial C(3)OH with the same H(2)ax proton, whereas in the trans-configuration of the hexahydropyrimidine ring, a cross-peak (OHax, H(2)eq) appears in the spectrum.

In the 1H NMR spectra of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4att, 4a–dct, which have the trans-configuration of the hexahydropyrimidine ring, the signal of the H(3) proton has the form of an unresolved or poorly resolved multiplet at δH 3.27–3.53 ppm with the constant 3JH,H ≈ 2.2 Hz, which indicates its equatorial position. Whereas for compounds 4atc, 4a–dcc, which have the cis-configuration of the hexahydropyrimidine ring, the multiplet of the H(3) signal at δH 3.21–3.32 ppm contains two constants 3JHax,Hax = 10.4–10.8 Hz with the neighboring methylene protons, which indicates its axial position.

Figure 4 exhibits the fragments of the 1H NMR spectra of diastereomers 4acc, 4act, 4att and 4atc clearly demonstrating the main differences.

![[1860-5397-21-209-4]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-209-4.jpg?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: The fragments of the 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) of diastereomers 4acc (a), 4аct (b), 4аtt (c), 4atc (d).

Figure 4: The fragments of the 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) of diastereomers 4acc (a), 4аct (b), 4аtt (c...

An interesting feature was found in the 1H NMR spectra of diastereomers 4a–c. In the compounds with the trans-configuration of the piperidone ring, the normal upfield-downfield relation of axial and equatorial shifts of methylene protons at C(9) is observed, i.e., the value of Δ9ea = δeq – δax is positive. With the cis-configuration of the piperidone ring, the chemical shifts of axial and equatorial shifts of methylene protons at C(9) are inverted and Δ9ea < 0 (see Table 4, Figure 4).

Table 4: The difference in chemical shifts Δea = δeq – δax of diastereotopic protons at C(9) for compounds 4a–d.

| No | R | Δ9ea | No | R | Δ9ea | No | R | Δ9ea | No | R | Δ9ea |

| 4acc | Me | –0.06 | 4atc | Me | +0.18 | 4btc | Et | +0.30 | 4dcc | Ph | +0.25 |

| 4act | Me | –0.06 | 4bct | Et | –0.12 | 4ccc | Bu | –0.12 | 4dct | Ph | +0.29 |

| 4att | Me | +0.02 | 4bcc | Et | –0.12 | 4cct | Bu | –0.12 | |||

In the 19F NMR spectra, the CF3 group of diastereomeric octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones 4att and 4atc, 4btc with the trans-configuration of the substituents in the piperidone ring shows upfield shifts (δF 79.50–79.61 ppm) compared with the cis-analogues 4a–dcc, 4a–dct (δF 79.92–80.09 ppm).

The configurations of diastereomers 5ctc and 5ctt were established using XRD (Figure 3). Figure 5 shows a fragment of the 1H NMR spectra of hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones 5ctc (a) and 5ctt (b) demonstrating the differences in the chemical shifts of the H(2) proton, which is located at the stereocenter, as well as other protons of the oxazolidine ring, which are affected by the change in configuration.

![[1860-5397-21-209-5]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-209-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: Fragments of 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) of hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-ones 5ctc (a) and 5ctt (b).

Figure 5: Fragments of 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) of hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-ones 5ctc (a) an...

In the 2D NOESY spectra of compounds 5ctc and 5ctt (R = Bu) and the other hexahydrooxazolopyridones 5a,b (R = Me, Et), similar correlations are observed, which allows us to determine their stereoconfiguration. For stereochemical assignments the key cross-peaks are: (OH, H(8A)), (H(8A), R) for the trans-configuration of the piperidone ring, (H(2), R) for the trans-configuration of the oxazolidine ring, and (H(1'), R) for the cis-configuration of the oxazolidine ring.

In the 19F NMR spectra, the signals of the CF3 group are recorded for hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones 5a–ctc at δF 79.65–79.66 ppm and for 5a–ctt at δF 79.73–79.74 ppm.

In this work, we investigated the biological properties of the synthesized compounds. We focused primarily on their potential antiviral activity, since a moderate anti-influenza effect of the related octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones was previously revealed [24]. The series of bicycles 4att, 4a–dct, 4atc, 4acc, 5ctc were tested against influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) virus on the MDCK cell line using ribavirin as a reference (Table 5).

Table 5: Antiviral activity of heterocycles 4 and 5 against influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) in MDCK cells.

| entry | No | influenza A virus (MDCK cells) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC50, μM | IC50, μM | SI | ||

| 1 | 4act | >111 | 372 | 0 |

| 2 | 4att | >1118 | 86 | 13 |

| 3 | 4atc | >1118 | 935 | 1 |

| 4 | 4acc | >1118 | >1118 | 1 |

| 5 | 4bct | >1062 | 223 | 5 |

| 6 | 4cct | >966 | 454 | 2 |

| 7 | 4dct | >908 | 759 | 1 |

| 8 | 5ctc | >966 | >966 | 1 |

| ribavirin | >2130 | 36 ± 6 | 59 | |

Of all the tested compounds, octahydropyridopyrimidinone 4att (IC50 86 μM, SI = 13) showed moderate antiviral activity. However, the value of selectivity index (SI) did not exceed that of reference compound ribavirin (Table 5, entry 2). In addition, this entire series of compounds is distinguished by the absence of cytotoxicity towards MDCK cells.

Conclusion

To sum up, we have, for the first time, demonstrated the possibility of 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol being involved in cyclization as an ambident N,N- and N,O-nucleophile. As a result, the three-component reaction of 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol with ethyl trifluoroacetoacetate and methyl ketones leads to two types of heterocycles: octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-ones and hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridin-5-ones. The cyclization direction is influenced by the substituent in the methyl ketone component, since, with acetone, the octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinone formation predominates, and with the elongation of the alkyl substituent in methyl ketone both processes become competitive. However, the use of bifunctional AcOH/Et3N catalysis leads to an increase in the regioselectivity of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones formation. In contrast, the cyclization with acetophenone occurs regiospecifically, yielding only octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones.

The presence of three chiral centers in the synthesized bicycles leads to the formation of hexahydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridones as two diastereomers, and octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones are formed as a mixture of two to four diastereomers. Diastereoselectivity correlates with the size of the alkyl substituent in the methyl ketone component. The tendency to increase the number of diastereomers of octahydropyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones is caused by the appearance of an additional asymmetric center in the starting 1,3-diaminopropan-2-ol, as opposed to the reactions with 1,3-diaminopropane [24]. The diastereoselectivity of cyclization with acetophenone depends on the reaction conditions: in the absence of a catalyst, the cis,trans-isomer is preferentially formed, whereas dual acid-base catalysis favors the formation of the other cis,cis-diastereomer.

The obtained hydrogenated oxazolo- and pyrimido-condensed pyridones are of interest for biological testing, which is confirmed by the discovery of an antiviral agent with moderate activity against the influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) among them.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: General synthetic procedures, characterization data, XRD analysis data and copies of 1H, 19F, 13C NMR spectra, IR spectra, HRMS spectra of all synthesized compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.8 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Zhu, J.; Bienayme, H., Eds. Multicomponent Reactions; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2005.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nandi, S.; Jamatia, R.; Sarkar, R.; Sarkar, F. K.; Alam, S.; Pal, A. K. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202201901. doi:10.1002/slct.202201901

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cioc, R. C.; Ruijter, E.; Orru, R. V. A. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2958–2975. doi:10.1039/c4gc00013g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hantzsch, A. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1890, 23, 1474–1476. doi:10.1002/cber.189002301243

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Du, X.-X.; Zi, Q.-X.; Wu, Y.-M.; Jin, Y.; Lin, J.; Yan, S.-J. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1505–1516. doi:10.1039/c8gc03698e

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Biginelli, P. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1891, 24, 1317–1319. doi:10.1002/cber.189102401228

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kappe, C. O. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 6937–6963. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)87971-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gülten, Ş.; Gezer, U.; Gündoğan, E. A. Lett. Org. Chem. 2020, 17, 366–371. doi:10.2174/1570178616666190819142221

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2023, 72, 103–129. doi:10.1007/s11172-023-3717-1

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Pryadeina, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Kodess, M. I.; Ulomskii, E. N.; Rusinov, V. L. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 40, 902–907. doi:10.1023/b:rujo.0000044558.47152.65

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tkachenko, I. G.; Komykhov, S. A.; Musatov, V. I.; Shishkina, S. V.; Dyakonenko, V. V.; Shvets, V. N.; Diachkov, M. V.; Chebanov, V. A.; Desenko, S. M. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 2390–2397. doi:10.3762/bjoc.15.231

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tkachenko, I. G.; Komykhov, S. A.; Gladkov, E. S.; Musatov, V. I.; Chebanov, V. A.; Desenko, S. M. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2019, 55, 392–396. doi:10.1007/s10593-019-02470-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Q.; Jiang, L.-L.; Chen, C.-N.; Yang, G.-F. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2009, 46, 139–148. doi:10.1002/jhet.1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, T.; Yao, C.; Lei, S.; Yu, C.; Tu, S. Chin. J. Chem. 2011, 29, 2427–2432. doi:10.1002/cjoc.201180412

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shaabani, A.; Rahmati, A.; Rezayan, A. H.; Darvishi, M.; Badri, Z.; Sarvari, A. QSAR Comb. Sci. 2007, 26, 973–979. doi:10.1002/qsar.200620024

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rahmati, A. Chem. Pap. 2011, 65, 536–541. doi:10.2478/s11696-011-0034-1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bhatt, J. D.; Patel, T. S.; Chudasama, C. J.; Patel, K. D. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 3632–3640. doi:10.1002/slct.201702285

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gibadullina, N. N.; Latypova, D. R.; Novikov, R. A.; Tomilov, Y. V.; Dokichev, V. A. ARKIVOC 2017, No. iv, 222–235. doi:10.24820/ark.5550190.p010.003

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dayakar, C.; Raju, B. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 9388–9392. doi:10.1002/slct.201801430

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Malysheva, K. O.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Gerasimova, N. A.; Evstigneeva, N. P.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 71, 1687–1700. doi:10.1007/s11172-022-3579-y

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Saloutin, V. I. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 6306–6314. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201500822

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Saloutin, V. I. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 3986–3991. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201700683

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2020, 69, 2163–2166. doi:10.1007/s11172-020-3016-z

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Volobueva, A. S.; Slita, A. V.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Misiurina, M. A.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Saloutin, V. I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2021, 241, 109686. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109686

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] -

Saloutin, V. I.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Burgart, Y. V. Pure Appl. Chem. 2020, 92, 1265–1275. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-1216

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Yakovleva, E. I.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Sinegubova, E. O.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Shtro, A. A.; Galochkina, A. V.; Nikolaeva, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 9925–9935. doi:10.1039/d1ob01843d

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Surnina, E. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Saloutin, V. I. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100709. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100709

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Surnina, E. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 59, 2147–2156. doi:10.1134/s1070428023120126

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Sadretdinova, L. S.; Evstigneeva, N. P.; Gerasimova, N. A.; Saloutin, V. I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 4273–4280. doi:10.1039/c9ob00293f

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Nair, A. S.; Singh, A. K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Sukumaran, S.; Koyiparambath, V. P.; Pappachen, L. K.; Rangarajan, T. M.; Kim, H.; Mathew, B. Processes 2022, 10, 2054. doi:10.3390/pr10102054

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deeks, E. D. Drugs 2018, 78, 1643–1650. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-0993-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scott, L. J. Drugs 2020, 80, 323–328. doi:10.1007/s40265-020-01264-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kim, S.-H.; Jung, E.; Yoon, M. K.; Kwon, O. H.; Hwang, D.-M.; Kim, D.-W.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.-M.; Yim, H. J. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 788, 54–64. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.06.016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Burriss, A.; Edmunds, A. J. F.; Emery, D.; Hall, R. G.; Jacob, O.; Schaetzer, J. Pest Manage. Sci. 2018, 74, 1228–1238. doi:10.1002/ps.4806

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Toquin, V.; Latorse, M.-P.; Beffa, R. Fluopicolide: A New Anti-oomycete Fungicide. In Modern Crop Protection Compounds; Jeschke, P.; Witschel, M.; Krämer, W.; Schirmer, U., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; pp 871–878. doi:10.1002/9783527699261.ch21

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Schleker, A. S. S.; Rist, M.; Matera, C.; Damijonaitis, A.; Collienne, U.; Matsuoka, K.; Habash, S. S.; Twelker, K.; Gutbrod, O.; Saalwächter, C.; Windau, M.; Matthiesen, S.; Stefanovska, T.; Scharwey, M.; Marx, M. T.; Geibel, S.; Grundler, F. M. W. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11954. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-15782-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lahm, G. P.; Desaeger, J.; Smith, B. K.; Pahutski, T. F.; Rivera, M. A.; Meloro, T.; Kucharczyk, R.; Lett, R. M.; Daly, A.; Smith, B. T.; Cordova, D.; Thoden, T.; Wiles, J. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1572–1575. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.029

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, X.-H.; Li, J.; Shi, J. B.; Song, B.-A.; Qi, X.-B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 51, 294–299. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.040

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hou, J.-Z.; Ye, J. C.; Pu, J. J.; Liu, H.; Ding, W.; Zheng, H.; Liu, D. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 66. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01077-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

De, S.; Kumar S K, A.; Shah, S. K.; Kazi, S.; Sarkar, N.; Banerjee, S.; Dey, S. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 15385–15406. doi:10.1039/d2ra01571d

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Marinescu, M.; Popa, C.-V. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5659. doi:10.3390/ijms23105659

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fluorine in Heterocyclic Chemistry Volume 2, 6-Membered Heterocycles; Nenajdenko, V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-04435-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Petrov, V. A., Ed. Fluorinated Heterocyclic Compounds: Synthesis, Chemistry, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. doi:10.1002/9780470528952

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, M.; Tao, X.; Li, J.; Shan, D.; Lv, L. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2017, 14, 350–356. doi:10.2174/1570193x14666170511122820

Return to citation in text: [1] -

da Silva, E. T.; de Andrade, G. F.; da Silva Araújo, A.; Lourenço, M. C. S.; de Souza, M. V. N. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 157, 105596. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105596

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Stalling, T.; Pauly, J.; Schmidtmann, M.; Martens, J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 833–843. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301213

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Caballero, E.; Manzano, J. I.; Puebla, P.; Castanys, S.; Gamarro, F.; San Feliciano, A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 6272–6275. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.07.100

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rai, S.; Bishnoi, A.; Fatma, S.; Shukla, S.; Devi, P.; Singh, V. Polycyclic Aromat. Compd. 2024, 44, 2752–2774. doi:10.1080/10406638.2023.2222210

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mane, U. R.; Mohanakrishnan, D.; Sahal, D.; Murumkar, P. R.; Giridhar, R.; Yadav, M. R. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 79, 422–435. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.04.031

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jadhav, S. B.; Fatema, S.; Patil, R. B.; Sangshetti, J. N.; Farooqui, M. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 3299–3313. doi:10.1002/jhet.2950

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ran, K.; Zeng, J.; Wan, G.; He, X.; Feng, Z.; Xiang, W.; Wei, W.; Hu, X.; Wang, N.; Liu, Z.; Yu, L. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 220, 113499. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113499

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Smith, R. L.; Barrett, R. J.; Sanders-Bush, E. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 275, 1050–1057. doi:10.1016/s0022-3565(25)12094-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meltzer, H. Y.; Simonovic, M.; Gudelsky, G. A. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1983, 92, 83–89. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90111-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Awouters, F.; Vermeire, J.; Smeyers, F.; Vermote, P.; van Beek, R.; Niemegeers, C. J. E. Drug Dev. Res. 1986, 8, 95–102. doi:10.1002/ddr.430080112

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Someno, T.; Kunimoto, S.; Nakamura, H.; Naganawa, H.; Ikeda, D. J. Antibiot. 2005, 58, 56–60. doi:10.1038/ja.2005.6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kunimoto, S.; Lu, J.; Esumi, H.; Yamazaki, Y.; Kinoshita, N.; Honma, Y.; Hamada, M.; Ohsono, M.; Ishizuka, M.; Takeuchi, T. J. Antibiot. 2003, 56, 1004–1011. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.56.1004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhan, T.; Yang, L.; Chen, Q.; Weng, R.; Liu, X.; Feng, X. CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 2101–2110. doi:10.31635/ccschem.022.202202405

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sanchez, C. A.; Gadais, C.; Diarra, S.; Bordessa, A.; Lensen, N.; Chelain, E.; Brigaud, T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 6771–6775. doi:10.1039/d1ob01173a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, J.; DeVita, R. J.; Doss, G. A.; Goulet, M. T.; Wyvratt, M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 593–594. doi:10.1021/ja983389n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tsoung, J.; Bogdan, A. R.; Kantor, S.; Wang, Y.; Charaschanya, M.; Djuric, S. W. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 1073–1084. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02520

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tatsumi, K.; Fujihara, T.; Terao, J.; Tsuji, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 3245–3248. doi:10.1002/adsc.201800704

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Silpa, L.; Niepceron, A.; Laurent, F.; Brossier, F.; Pénichon, M.; Enguehard-Gueiffier, C.; Abarbri, M.; Silvestre, A.; Petrignet, J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 114–120. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.11.018

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pryadeina, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kodess, M. I.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2005, 54, 2841–2845. doi:10.1007/s11172-006-0198-y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shidlovskii, A. F.; Peregudov, A. S.; Averkiev, B. B.; Antipin, M. Y.; Chkanikov, N. D. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2004, 53, 2060–2070. doi:10.1007/s11172-005-0073-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harriman, G. C. B.; Chi, S.; Zhang, M.; Crowe, A.; Bennett, R. A.; Parsons, I. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 3659–3662. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(03)00700-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Smith, M. B. March’s advanced organic chemistry reactions, mechanisms, and structure, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pretsch, E.; Bühlmann, P.; Affolter, C. Structure determination of organic compounds, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04201-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eliel, E. L.; Wilen, S. H.; Doyle, M. P. Basic organic stereochemistry; Wiley Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 2001.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 40. | De, S.; Kumar S K, A.; Shah, S. K.; Kazi, S.; Sarkar, N.; Banerjee, S.; Dey, S. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 15385–15406. doi:10.1039/d2ra01571d |

| 41. | Marinescu, M.; Popa, C.-V. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5659. doi:10.3390/ijms23105659 |

| 42. | Fluorine in Heterocyclic Chemistry Volume 2, 6-Membered Heterocycles; Nenajdenko, V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-04435-4 |

| 43. | Petrov, V. A., Ed. Fluorinated Heterocyclic Compounds: Synthesis, Chemistry, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. doi:10.1002/9780470528952 |

| 44. | Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, M.; Tao, X.; Li, J.; Shan, D.; Lv, L. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2017, 14, 350–356. doi:10.2174/1570193x14666170511122820 |

| 45. | da Silva, E. T.; de Andrade, G. F.; da Silva Araújo, A.; Lourenço, M. C. S.; de Souza, M. V. N. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 157, 105596. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105596 |

| 46. | Stalling, T.; Pauly, J.; Schmidtmann, M.; Martens, J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 833–843. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301213 |

| 53. | Meltzer, H. Y.; Simonovic, M.; Gudelsky, G. A. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1983, 92, 83–89. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90111-5 |

| 54. | Awouters, F.; Vermeire, J.; Smeyers, F.; Vermote, P.; van Beek, R.; Niemegeers, C. J. E. Drug Dev. Res. 1986, 8, 95–102. doi:10.1002/ddr.430080112 |

| 51. | Ran, K.; Zeng, J.; Wan, G.; He, X.; Feng, Z.; Xiang, W.; Wei, W.; Hu, X.; Wang, N.; Liu, Z.; Yu, L. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 220, 113499. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113499 |

| 52. | Smith, R. L.; Barrett, R. J.; Sanders-Bush, E. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 275, 1050–1057. doi:10.1016/s0022-3565(25)12094-6 |

| 49. | Mane, U. R.; Mohanakrishnan, D.; Sahal, D.; Murumkar, P. R.; Giridhar, R.; Yadav, M. R. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 79, 422–435. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.04.031 |

| 50. | Jadhav, S. B.; Fatema, S.; Patil, R. B.; Sangshetti, J. N.; Farooqui, M. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 3299–3313. doi:10.1002/jhet.2950 |

| 47. | Caballero, E.; Manzano, J. I.; Puebla, P.; Castanys, S.; Gamarro, F.; San Feliciano, A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 6272–6275. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.07.100 |

| 48. | Rai, S.; Bishnoi, A.; Fatma, S.; Shukla, S.; Devi, P.; Singh, V. Polycyclic Aromat. Compd. 2024, 44, 2752–2774. doi:10.1080/10406638.2023.2222210 |

| 55. | Someno, T.; Kunimoto, S.; Nakamura, H.; Naganawa, H.; Ikeda, D. J. Antibiot. 2005, 58, 56–60. doi:10.1038/ja.2005.6 |

| 56. | Kunimoto, S.; Lu, J.; Esumi, H.; Yamazaki, Y.; Kinoshita, N.; Honma, Y.; Hamada, M.; Ohsono, M.; Ishizuka, M.; Takeuchi, T. J. Antibiot. 2003, 56, 1004–1011. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.56.1004 |

| 57. | Zhan, T.; Yang, L.; Chen, Q.; Weng, R.; Liu, X.; Feng, X. CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 2101–2110. doi:10.31635/ccschem.022.202202405 |

| 58. | Sanchez, C. A.; Gadais, C.; Diarra, S.; Bordessa, A.; Lensen, N.; Chelain, E.; Brigaud, T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 6771–6775. doi:10.1039/d1ob01173a |

| 66. | Smith, M. B. March’s advanced organic chemistry reactions, mechanisms, and structure, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2013. |

| 24. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Volobueva, A. S.; Slita, A. V.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Misiurina, M. A.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Saloutin, V. I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2021, 241, 109686. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109686 |

| 26. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Yakovleva, E. I.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Sinegubova, E. O.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Shtro, A. A.; Galochkina, A. V.; Nikolaeva, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 9925–9935. doi:10.1039/d1ob01843d |

| 24. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Volobueva, A. S.; Slita, A. V.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Misiurina, M. A.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Saloutin, V. I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2021, 241, 109686. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109686 |

| 25. | Saloutin, V. I.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Burgart, Y. V. Pure Appl. Chem. 2020, 92, 1265–1275. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-1216 |

| 29. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Sadretdinova, L. S.; Evstigneeva, N. P.; Gerasimova, N. A.; Saloutin, V. I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 4273–4280. doi:10.1039/c9ob00293f |

| 60. | Tsoung, J.; Bogdan, A. R.; Kantor, S.; Wang, Y.; Charaschanya, M.; Djuric, S. W. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 1073–1084. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02520 |

| 61. | Tatsumi, K.; Fujihara, T.; Terao, J.; Tsuji, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 3245–3248. doi:10.1002/adsc.201800704 |

| 62. | Silpa, L.; Niepceron, A.; Laurent, F.; Brossier, F.; Pénichon, M.; Enguehard-Gueiffier, C.; Abarbri, M.; Silvestre, A.; Petrignet, J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 114–120. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.11.018 |

| 63. | Pryadeina, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kodess, M. I.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2005, 54, 2841–2845. doi:10.1007/s11172-006-0198-y |

| 64. | Shidlovskii, A. F.; Peregudov, A. S.; Averkiev, B. B.; Antipin, M. Y.; Chkanikov, N. D. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2004, 53, 2060–2070. doi:10.1007/s11172-005-0073-2 |

| 65. | Harriman, G. C. B.; Chi, S.; Zhang, M.; Crowe, A.; Bennett, R. A.; Parsons, I. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 3659–3662. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(03)00700-7 |

| 59. | Jiang, J.; DeVita, R. J.; Doss, G. A.; Goulet, M. T.; Wyvratt, M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 593–594. doi:10.1021/ja983389n |

| 21. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Saloutin, V. I. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 6306–6314. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201500822 |

| 22. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Saloutin, V. I. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 3986–3991. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201700683 |

| 23. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2020, 69, 2163–2166. doi:10.1007/s11172-020-3016-z |

| 24. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Volobueva, A. S.; Slita, A. V.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Misiurina, M. A.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Saloutin, V. I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2021, 241, 109686. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109686 |

| 68. | Eliel, E. L.; Wilen, S. H.; Doyle, M. P. Basic organic stereochemistry; Wiley Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 2001. |

| 24. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Volobueva, A. S.; Slita, A. V.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Misiurina, M. A.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Saloutin, V. I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2021, 241, 109686. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109686 |

| 67. | Pretsch, E.; Bühlmann, P.; Affolter, C. Structure determination of organic compounds, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04201-4 |

| 1. | Zhu, J.; Bienayme, H., Eds. Multicomponent Reactions; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2005. |

| 2. | Nandi, S.; Jamatia, R.; Sarkar, R.; Sarkar, F. K.; Alam, S.; Pal, A. K. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202201901. doi:10.1002/slct.202201901 |

| 3. | Cioc, R. C.; Ruijter, E.; Orru, R. V. A. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2958–2975. doi:10.1039/c4gc00013g |

| 10. | Pryadeina, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Kodess, M. I.; Ulomskii, E. N.; Rusinov, V. L. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 40, 902–907. doi:10.1023/b:rujo.0000044558.47152.65 |

| 11. | Tkachenko, I. G.; Komykhov, S. A.; Musatov, V. I.; Shishkina, S. V.; Dyakonenko, V. V.; Shvets, V. N.; Diachkov, M. V.; Chebanov, V. A.; Desenko, S. M. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 2390–2397. doi:10.3762/bjoc.15.231 |

| 12. | Tkachenko, I. G.; Komykhov, S. A.; Gladkov, E. S.; Musatov, V. I.; Chebanov, V. A.; Desenko, S. M. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2019, 55, 392–396. doi:10.1007/s10593-019-02470-0 |

| 13. | Chen, Q.; Jiang, L.-L.; Chen, C.-N.; Yang, G.-F. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2009, 46, 139–148. doi:10.1002/jhet.1 |

| 14. | Li, T.; Yao, C.; Lei, S.; Yu, C.; Tu, S. Chin. J. Chem. 2011, 29, 2427–2432. doi:10.1002/cjoc.201180412 |

| 15. | Shaabani, A.; Rahmati, A.; Rezayan, A. H.; Darvishi, M.; Badri, Z.; Sarvari, A. QSAR Comb. Sci. 2007, 26, 973–979. doi:10.1002/qsar.200620024 |

| 16. | Rahmati, A. Chem. Pap. 2011, 65, 536–541. doi:10.2478/s11696-011-0034-1 |

| 20. | Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Malysheva, K. O.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Gerasimova, N. A.; Evstigneeva, N. P.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 71, 1687–1700. doi:10.1007/s11172-022-3579-y |

| 26. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Yakovleva, E. I.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Sinegubova, E. O.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Shtro, A. A.; Galochkina, A. V.; Nikolaeva, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 9925–9935. doi:10.1039/d1ob01843d |

| 9. | Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2023, 72, 103–129. doi:10.1007/s11172-023-3717-1 |

| 20. | Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Malysheva, K. O.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Gerasimova, N. A.; Evstigneeva, N. P.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 71, 1687–1700. doi:10.1007/s11172-022-3579-y |

| 6. | Biginelli, P. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1891, 24, 1317–1319. doi:10.1002/cber.189102401228 |

| 7. | Kappe, C. O. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 6937–6963. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)87971-0 |

| 8. | Gülten, Ş.; Gezer, U.; Gündoğan, E. A. Lett. Org. Chem. 2020, 17, 366–371. doi:10.2174/1570178616666190819142221 |

| 28. | Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Surnina, E. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 59, 2147–2156. doi:10.1134/s1070428023120126 |

| 4. | Hantzsch, A. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1890, 23, 1474–1476. doi:10.1002/cber.189002301243 |

| 5. | Du, X.-X.; Zi, Q.-X.; Wu, Y.-M.; Jin, Y.; Lin, J.; Yan, S.-J. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1505–1516. doi:10.1039/c8gc03698e |

| 29. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Sadretdinova, L. S.; Evstigneeva, N. P.; Gerasimova, N. A.; Saloutin, V. I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 4273–4280. doi:10.1039/c9ob00293f |

| 21. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Saloutin, V. I. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 6306–6314. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201500822 |

| 22. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Kudyakova, Y. S.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Saloutin, V. I. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 3986–3991. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201700683 |

| 23. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2020, 69, 2163–2166. doi:10.1007/s11172-020-3016-z |

| 24. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Volobueva, A. S.; Slita, A. V.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Misiurina, M. A.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Saloutin, V. I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2021, 241, 109686. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109686 |

| 26. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Yakovleva, E. I.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Sinegubova, E. O.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Shtro, A. A.; Galochkina, A. V.; Nikolaeva, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 9925–9935. doi:10.1039/d1ob01843d |

| 20. | Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Malysheva, K. O.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Gerasimova, N. A.; Evstigneeva, N. P.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 71, 1687–1700. doi:10.1007/s11172-022-3579-y |

| 27. | Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Surnina, E. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Saloutin, V. I. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202100709. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100709 |

| 9. | Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2023, 72, 103–129. doi:10.1007/s11172-023-3717-1 |

| 24. | Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Burgart, Y. V.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Volobueva, A. S.; Slita, A. V.; Esaulkova, I. L.; Misiurina, M. A.; Zarubaev, V. V.; Saloutin, V. I. J. Fluorine Chem. 2021, 241, 109686. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2020.109686 |

| 17. | Bhatt, J. D.; Patel, T. S.; Chudasama, C. J.; Patel, K. D. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 3632–3640. doi:10.1002/slct.201702285 |

| 18. | Gibadullina, N. N.; Latypova, D. R.; Novikov, R. A.; Tomilov, Y. V.; Dokichev, V. A. ARKIVOC 2017, No. iv, 222–235. doi:10.24820/ark.5550190.p010.003 |

| 19. | Dayakar, C.; Raju, B. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 9388–9392. doi:10.1002/slct.201801430 |

| 25. | Saloutin, V. I.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Kushch, S. O.; Khudina, O. G.; Ezhikova, M. A.; Kodess, M. I.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Burgart, Y. V. Pure Appl. Chem. 2020, 92, 1265–1275. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-1216 |

| 20. | Kushch, S. O.; Goryaeva, M. V.; Burgart, Y. V.; Triandafilova, G. A.; Malysheva, K. O.; Krasnykh, O. P.; Gerasimova, N. A.; Evstigneeva, N. P.; Saloutin, V. I. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 71, 1687–1700. doi:10.1007/s11172-022-3579-y |

| 30. | Nair, A. S.; Singh, A. K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Sukumaran, S.; Koyiparambath, V. P.; Pappachen, L. K.; Rangarajan, T. M.; Kim, H.; Mathew, B. Processes 2022, 10, 2054. doi:10.3390/pr10102054 |

| 38. | Liu, X.-H.; Li, J.; Shi, J. B.; Song, B.-A.; Qi, X.-B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 51, 294–299. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.040 |

| 39. | Hou, J.-Z.; Ye, J. C.; Pu, J. J.; Liu, H.; Ding, W.; Zheng, H.; Liu, D. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 66. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01077-3 |

| 36. | Schleker, A. S. S.; Rist, M.; Matera, C.; Damijonaitis, A.; Collienne, U.; Matsuoka, K.; Habash, S. S.; Twelker, K.; Gutbrod, O.; Saalwächter, C.; Windau, M.; Matthiesen, S.; Stefanovska, T.; Scharwey, M.; Marx, M. T.; Geibel, S.; Grundler, F. M. W. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11954. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-15782-7 |

| 37. | Lahm, G. P.; Desaeger, J.; Smith, B. K.; Pahutski, T. F.; Rivera, M. A.; Meloro, T.; Kucharczyk, R.; Lett, R. M.; Daly, A.; Smith, B. T.; Cordova, D.; Thoden, T.; Wiles, J. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1572–1575. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.029 |

| 34. | Burriss, A.; Edmunds, A. J. F.; Emery, D.; Hall, R. G.; Jacob, O.; Schaetzer, J. Pest Manage. Sci. 2018, 74, 1228–1238. doi:10.1002/ps.4806 |

| 35. | Toquin, V.; Latorse, M.-P.; Beffa, R. Fluopicolide: A New Anti-oomycete Fungicide. In Modern Crop Protection Compounds; Jeschke, P.; Witschel, M.; Krämer, W.; Schirmer, U., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; pp 871–878. doi:10.1002/9783527699261.ch21 |

| 33. | Kim, S.-H.; Jung, E.; Yoon, M. K.; Kwon, O. H.; Hwang, D.-M.; Kim, D.-W.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.-M.; Yim, H. J. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 788, 54–64. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.06.016 |

© 2025 Kushch et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.