Abstract

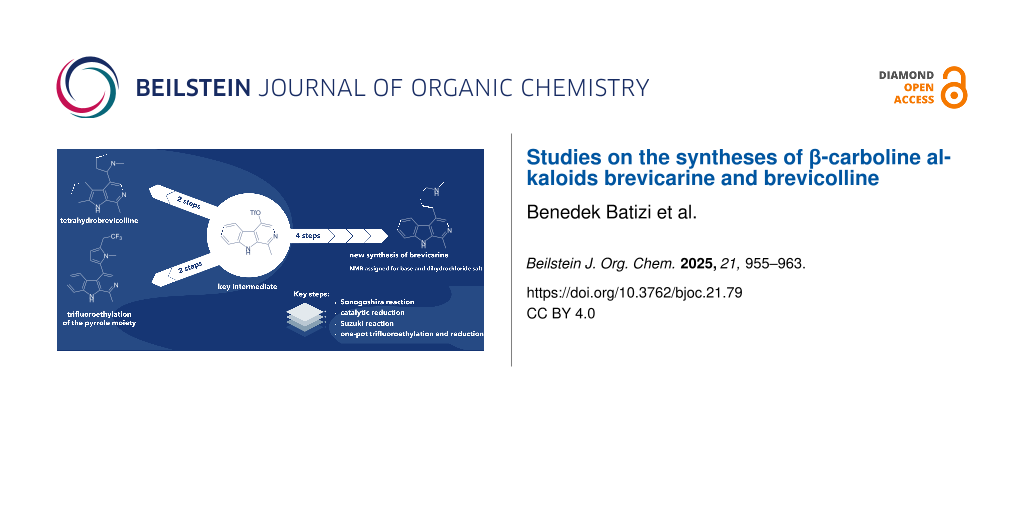

A new total synthesis of the β-carboline alkaloid brevicarine is disclosed. The synthesis was carried out starting from an aromatic triflate key intermediate, allowing the introduction of various substituents into position 4 of β-carboline by cross-coupling reactions. Thanks to its scalability, this novel approach ensures a broad accessibility to the target compound for potential pharmacological measurements. Using detailed NMR studies, the NMR signals have been assigned for both the base and its dihydrochloride salt for further confirming their structures. A new synthesis of the related alkaloid brevicolline was also attempted from the same intermediate. However, after successful coupling of β-carboline with N-methylpyrrole, the trials to saturate the pyrrole ring under various conditions led to unexpected reactions: reduction of ring A of the β-carboline skeleton or trifluoroethylation of the pyrrole moiety occurred, leading to interesting and potentially useful derivatives.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Carex brevicollis DC is a widely distributed sedge which can be mainly found in the Central and South-Eastern European region. It contains several alkaloids, including β-carboline alkaloids (S)-brevicolline (S-(1)) and brevicarine (2, Figure 1) as the two main components [1-3]. Our long-standing interest in the chemistry of β-carbolines [4-18] has now focused our attention on these two alkaloids.

Figure 1: The structure of brevicolline ((S)-1) and brevicarine (2).

Figure 1: The structure of brevicolline ((S)-1) and brevicarine (2).

In a recent publication we disclosed a new total synthesis of racemic brevicolline ((±)-1) (Scheme 1) [9]. A prerequisite for the synthesis was the development of a new, versatile key triflate intermediate 3, which allowed the introduction of substituents attached by a C–C bond to position 4 of the β-carboline scaffold by cross-coupling reactions. Sonogashira reaction of compound 3 with N-(3-butynyl)phthalimide (4) led to coupled compound 5. Cleavage of the phthalimide group with methylhydrazine afforded butynylamine derivative 6. Cyclization of the latter to dihydropyrrole 7 and subsequent reduction resulted in compound 8, which was N-methylated to give racemic brevicolline ((±)-1). The natural product (S)-brevicolline ((S)-1) was finally obtained by chiral chromatography of the corresponding racemate.

Scheme 1: Synthesis of racemic brevicolline ((±)-1) starting from 1-methyl-9H-β-carbolin-4-yl trifluoromethanesulfonate (3).

Scheme 1: Synthesis of racemic brevicolline ((±)-1) starting from 1-methyl-9H-β-carbolin-4-yl trifluoromethan...

To continue this work, we decided to attempt the synthesis of brevicarine (2), a structurally related alkaloid, as well. There are some published examples for the synthesis of brevicarine in the literature. The first semi-synthetic access to brevicarine (2) was achieved by a few-step transformation starting from brevicolline ((S)-1) isolated from natural sources (Scheme 2) [19]. When heating (S)-1 in benzoyl chloride, opening of the pyrrolidine ring and N-benzoylation occurred, resulting in compound 9. Debenzoylation of the latter to 10, followed by the catalytic hydrogenation of the C=C double bond in the side chain gave brevicarine (2).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of brevicarine (2) from brevicolline ((S)-1).

Scheme 2: Synthesis of brevicarine (2) from brevicolline ((S)-1).

The first total synthesis of brevicarine is shown in Scheme 3 [2,20,21]. Condensation of indole (11) with 1-methylpiperidone (12) gave compound 13 [22]. N-Alkylation of 13 with benzyl bromide, followed by treatment of the quaternary ammonium derivative 14 with the potassium salt of compound 15 resulted in the ring-opened derivative 16. Removal of the benzylthiocarbonyl moiety, then Beckmann rearrangement of the oxime obtained from ketone 17 and subsequent cyclization gave β-carboline derivative 18, which was dehydrogenated and debenzylated to brevicarine (2), isolated as a dihydrochloride salt.

Scheme 3: First total synthesis of brevicarine (2).

Scheme 3: First total synthesis of brevicarine (2).

Müller et al. accomplished an alternative synthesis of brevicarine (2, Scheme 4) [23]. Compound 21 was obtained by treatment of nitrovinylindole 19 with N-methylpyrrole (20). Catalytic hydrogenation of the pyrrole ring and the nitro group of 21 under extremely harsh conditions (100 °C, 130 bar), followed by N-acetylation gave a mixture of diastereomeric racemates 22, which was cyclized to a diastereomeric mixture of β-carboline derivatives 23. Heating of 23 in pivalic acid in the presence of a catalytic amount of trifluoroacetic acid gave brevicarine (2).

Scheme 4: Multistep synthesis of brevicarine (2) starting from nitrovinylindole 19.

Scheme 4: Multistep synthesis of brevicarine (2) starting from nitrovinylindole 19.

The sedge Carex brevicollis DC has long been recognized for its ability to stimulate the contraction of smooth muscles [2]. This effect may be linked to the oxytocic activity of (S)-brevicolline ((S)-1), which has been studied on pregnant mammals [24,25]. (S)-Brevicolline, first isolated in 1960 [3], was tested in vitro and demonstrated antibacterial and antifungal properties due to its photosensitizing ability [26]. It was used in medical practice as an obstetrical drug and also in veterinary practice for treating infertility [2]. Experiments investigating the synthesis of brevicarine (2) from (S)-brevicolline ((S)-1) (see Scheme 2) and their biogenetic relationship suggest that (S)-brevicolline could serve as a biosynthetic intermediate of brevicarine (2) in plants [19].

Brevicarine (2), isolated in 1967 from Carex brevicollis DC [27], has also been identified in various other natural sources, including Tambourissa ficus (mauritian endemic fruit) [28], Asparagus racemosus (linn seed) [29] and a mixture extract of Phellinus linteus smilax corbularia and Phellinus linteus smilax glabra [30]. Literature reports indicate that brevicarine exhibits several pharmacological activities: it acts as an antioxidant [28], shows antibacterial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis [31], has antiproliferative effects against triple-negative breast cancer [32], serves as an agent against Parkinson's disease [29], and possesses skin anti-inflammatory properties [33]. Notably, the dihydrochloride salt of the alkaloid has been tested in vivo in rats, cats, and rabbits as an antiarrhythmic agent, demonstrating superior efficacy compared to the commercially available drugs quinidine and novocainamide [34]. N-Methylbrevicarine, a semi-synthetic derivative of the alkaloid, has been screened in silico for non-peptide malignant brain tumor (MBT) antagonist activity, showing hits on three MBT-containing proteins [35]. Although Carex brevicollis DC has been observed to have a teratogenic effect on animals [1,36], which could be linked with the presence of the two mentioned β-carboline alkaloids, further investigation is needed to prove this observation. However, the mentioned alkaloids have high potential as medications. Based on the above, research on the total synthesis of these alkaloids and their closely related derivatives is crucial for further confirming their structure and for ensuring their accessibility for pharmacological measurements.

Results and Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to develop a novel, scalable synthesis of brevicarine (2) and an alternative synthetic approach for the preparation of brevicolline (1), both based on the common key intermediate 3 [9]. The synthesis of brevicarine (2) (Scheme 5) started with the known synthesis of 5 from 3, followed by catalytic reduction of the triple bond of phthaloyl intermediate 5 to give compound 24. Removal of the phthalimide group with methylamine resulted in amine 25. Alternatively, the removal of the phthaloyl moiety from compound 5 to amine 6 using methylamine instead of the highly toxic and environmentally harmful methylhydrazine, which was used earlier [9], has been developed as a greener approach, followed by catalytic reduction of the triple bond also leading to compound 25.

Scheme 5: New synthesis variants for the preparation of brevicarine alkaloid (2) and its synthetic derivative N-methylbrevicarine (27).

Scheme 5: New synthesis variants for the preparation of brevicarine alkaloid (2) and its synthetic derivative ...

Our experiments for the N-monomethylation of the primary amino group of compound 25 by alkylation with methyl iodide or by Eschweiler–Clarke reductive amination with formaldehyde and formic acid were unsuccessful, because the dimethylated byproduct was also formed, even when one equivalent alkylating agent was used. Finally, our efforts were crowned by success. In order to completely avoid the possibility of overmethylation [37], the methyl group was introduced by N-formylation of the primary amine group of 25 to give congener 26, followed by reduction of the formyl group with borane–dimethyl sulfide complex [38] to result in brevicarine (2, isolated as its dihydrochloride salt). Based on the above results, Eschweiler–Clarke methylation of primary amine 25 was applied for the synthesis of N-methylbrevicarine (27) [39], a close structural analogue of alkaloid 2.

The NMR data of our synthesized brevicarine (2) base and dihydrochloride salt are summarized in Table 1. Although a rudimentary 1H NMR spectrum of isolated brevicarine (2) base and some of the NMR signals were reported in 1969 [39], the signals were not fully assigned. However, the mentioned signals are identical to those of our synthetic product. All other publications [19,23,24] confirmed the structure with IR and MS data, or by reactivity. Herein, we report the full set of assigned 1H and 13C NMR data for both the base and the dihydrochloride salt.

Table 1: Assigned 1H and 13C NMR data of brevicarine (2) base and its dihydrochloride salt.

|

|

||||

|

Atom

no. |

Synthetic brevicarine | Synthetic brevicarine dihydrochloride salt | ||

| 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz), δH | 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz), δC |

1H NMR (DMSO-d6,

600 MHz), δH |

13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz), δC | |

| 1 | – | 140.1 | – | 140.3 |

| 1’ | 2.72 (s, 3H) | 20.4 | 2.74 (s, 3H) | 20.2 |

| 2 | – | – | – | – |

| 3 | 7.99 (s, 1H) | 137.7 | 8.03 (s, 1H) | 137.4 |

| 4 | – | 129.0 | – | 128.4 |

| 4a | – | 125.1 | – | 125.3 |

| 4b | – | 121.1 | – | 121.0 |

| 5 | 8.13 (m, 1H) | 123.3 | 8.13 (m, 1H) | 123.4 |

| 6 | 7.25 (m, 1H) | 119.6 | 7.27 (m, 1H) | 119.7 |

| 7 | 7.53 (m, 1H) | 127.3 | 7.55 (m, 1H) | 127.6 |

| 8 | 7.61 (m, 1H) | 112.1 | 7.64 (m, 1H) | 112.2 |

| 8a | – | 140.5 | – | 140.6 |

| 9 | 11.57 (br s, 1H) | - | 11.70 (br s, 1H) | – |

| 9a | – | 134.5 | – | 134.5 |

| 10 | 3.11 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H) | 30.8 | 3.17 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H) | 30.2 |

| 11 | 1.75 (m, 2H) | 27.5 | 1.79 (m, 2H) | 26.3 |

| 12 | 1.55 (m, 2H) | 29.3 | 1.72 (m, 2H) | 25.4 |

| 13 | 2.50 (m, 2H) | 51.5 | 2.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H) | 48.3 |

| 14 | – | – | 8.56 (br s, 2H) | – |

| 15 | 2.25 (s, 3H) | 36.4 | 2.50 (s, 3H) | 32.6 |

In the course of our efforts devoted to elaborating a new and efficient synthesis of brevicarine (2), we encountered a surprising reaction (Scheme 6). Based on literature data, we expected to transform carbamate 28, obtained from amine 25 by ethoxycarbonylation, into brevicarine (2) by reduction with LiAlH4 [40,41]. However, to our surprise, the reduction stopped at the N-formyl (26) stage, the formation of brevicarine (2) could not be detected by LC–MS.

Scheme 6: Preparation of carbamate 28 and subsequent reduction with LiAlH4.

Scheme 6: Preparation of carbamate 28 and subsequent reduction with LiAlH4.

As regards our plans for an alternative synthesis of racemic brevicolline ((±)-1), our primary goal was the direct coupling of the pyrrole ring to compound 3, instead of its ring-closing construction shown in Scheme 1. Suzuki reaction of 3 with pyrrole boronic ester 29 gave pyrrolo-β-carboline 30 in excellent yield (Scheme 7). Our attempts for the selective saturation of the pyrrole ring of 30 by catalytic reduction were unsuccessful. When the hydrogenation was carried out under mild conditions (ambient temperature, 15 bar H2) in the presence of PtO2.H2O catalyst, overreduced product 31, i.e., the tetrahydro derivative of racemic brevicolline ((±)-1) was obtained in 91% yield.

Scheme 7: Experiments for the synthesis of racemic brevicolline ((±)-1), and formation of unexpected products.

Scheme 7: Experiments for the synthesis of racemic brevicolline ((±)-1), and formation of unexpected products....

Structure determination of 31 was supported by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, as well (Figure 2). Changing the catalyst [Pd(OH)2, Ru, Rh], did not alter the course of the reaction: the formation of compound 31 was always observed, and brevicolline ((±)-1) was not formed. Interestingly, our attempts made for the transformation of compound 31 by dehydrogenative aromatization to brevicolline ((±)-1) by using several reagents (DDQ, Pd/C, MnO2, CuCl2, I2, elemental sulfur, KMnO4) were also ineffective. Based on literature data [42,43], we attempted the selective reduction of the pyrrole ring of compound 30 with NaCNBH3 in TFA as well. Surprisingly, trifluoroethylated product 32 was isolated. The formation of this compound can also be explained on the basis of analogies described in the literature for trifluoroacetylation of aromatic ring systems with TFA [44,45]. Nevertheless, in our case, trifluoroacetylation of the pyrrole moiety of 30 by TFA and reduction of the carbonyl group of 33 with NaCNBH3 took place in one pot, which is unprecedented in the literature. It is worth mentioning that in a similar reaction of 30 with NaCNBH3 in acetic acid (instead of TFA) we did not observe any reaction, however, with NaBH4 (instead of NaCNBH3) in TFA, the formation of 32 was detected.

![[1860-5397-21-79-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-21-79-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: X-ray structure of compound 31.

Figure 2: X-ray structure of compound 31.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a new method for the synthesis of β-carboline alkaloid brevicarine has been elaborated rendering the preparation of larger amounts of the target compound possible. NMR data of brevicarine base and dihydrochloride salt were fully assigned for a further confirmation of their structure. In the course of the unsuccessful attempts for a new synthesis of brevicolline, we synthesized several new, potentially pharmacologically active β-carboline derivatives structurally close to the alkaloids brevicarine and brevicolline. These derivatives (25–28, 30–32) can also serve as versatile starting materials for the synthesis of new alkaloid analogues and other C(4)-substituted β-carbolines. Some surprising reactions were also observed, such as the unexpected formation of racemic tetrahydrobrevicolline and the trifluoroethylation of the pyrrole moiety, which can also serve as favorable starting points for further research.

Supporting Information

CCDC 2410549 (31) contain supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.ac.uk/data request/cif.

| Supporting Information File 1: ORTEP diagram of compound 31, synthetic procedures, IR, 1H, 13C, 19F and 2D NMR spectra of compounds 2, 5, 6, 24–28 and 30–32. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 7.2 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: Crystallographic information file of compound 31. | ||

| Format: CIF | Size: 45.8 KB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 3: Checkcif file for compound 31. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 155.7 KB | Download |

Funding

This work was prepared in the framework of 2020-1.1.2-PIACI-KFI-2020-00039 project with the support of the Ministry of Culture and Innovation from National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (Hungary). Project no. 2023-2.1.2-KDP-2023-00016 has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry for Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the KDP-2023 funding scheme.

Data Availability Statement

Additional research data generated and analyzed during this study is not shared.

References

-

Busqué, J.; Pedrosa, M. M.; Cabellos, B.; Muzquiz, M. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 1244–1254. doi:10.1007/s10886-010-9865-4

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Lazurjevski, G.; Terentjeva, I. Heterocycles 1976, 4, 1783–1816. doi:10.3987/r-1976-11-1783

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Terent'eva, I. Moldavii, Moldavsk. Tr. Inst. Khim. Akad. Nauk Kirg. SSR 1960, 21.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Szabó, T.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Molecules 2021, 26, 663. doi:10.3390/molecules26030663

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Földesi, T.; Grün, A.; Volk, B.; Keglevich, G.; Milen, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1953–1957. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.03.067

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 617–619. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.063

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Szabó, T.; Hazai, V.; Volk, B.; Simig, G.; Milen, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 1471–1475. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.04.044

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Szabó, T.; Dancsó, A.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 72–79. doi:10.1080/14786419.2019.1613401

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Szabó, T.; Görür, F. L.; Horváth, S.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Synthesis 2022, 54, 3867–3873. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1737830

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Pollák, P.; Garádi, Z.; Volk, B.; Dancsó, A.; Simig, G.; Milen, M. Nat. Prod. Res., in press. doi:10.1080/14786419.2024.2306600

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Szepesi Kovács, D.; Hajdu, I.; Mészáros, G.; Wittner, L.; Meszéna, D.; Tóth, E. Z.; Hegedűs, Z.; Ranđelović, I.; Tóvári, J.; Szabó, T.; Szilágyi, B.; Milen, M.; Keserű, G. M.; Ábrányi-Balogh, P. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 12802–12807. doi:10.1039/d1ra02132j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Dancsó, A.; Frigyes, D.; Volk, B.; Keglevich, G.; Milen, M. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 5711–5719. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.06.073

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Milen, M.; Hazai, L.; Kolonits, P.; Kalaus, G.; Szabó, L.; Gömöry, Á.; Szántay, C. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2005, 3, 118–136. doi:10.2478/bf02476243

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Milen, M.; Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Mucsi, Z.; Dancso, A.; Frigyes, D.; Pongo, L.; Keglevich, G. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013, 17, 1894–1902. doi:10.2174/13852728113179990035

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Volk, B.; Keglevich, G.; Milen, M. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2016, 1097, 48–60. doi:10.1016/j.comptc.2016.10.008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Milen, M.; Ábrányi-Balogh, P. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2016, 52, 996–998. doi:10.1007/s10593-017-1997-9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Milen, M.; Abranyi-Balogh, P.; Dancso, A.; Simig, G.; Keglevich, G. Lett. Org. Chem. 2010, 7, 377–382. doi:10.2174/157017810791514913

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Milen, M.; Hazai, L.; Kolonits, P.; Gömöry, Á.; Szántay, C.; Fekete, J. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2004, 27, 2921–2933. doi:10.1081/jlc-200030844

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vember, P. A.; Terentjeva, I. Khim. Prir. Soedin. 1969, 5, 404–406.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Kuchkova, K.; Semenov, A.; Terentjeva, I. Khim. Geterotsikl. Soedin. 1970, 197.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kuchkova, K.; Semenov, A.; Terentjeva, I. Acta Chim. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1971, 69, 367–371.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Powers, J. C. J. Org. Chem. 1965, 30, 2534–2540. doi:10.1021/jo01019a008

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Müller, W. H.; Preuß, R.; Winterfeldt, E. Chem. Ber. 1977, 110, 2424–2432. doi:10.1002/cber.19771100703

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Marcu, G. A. T. Nauchn. Konf. Molodykh Uch. Mold., Biol. S-kh. Nauki. 1965, 243.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Iasnetsov, V. S.; Sizov, P. I. Farmakol. Toksikol. (Moscow) 1972, 35, 201–203.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Towers, G. H. N.; Abramowski, Z. J. Nat. Prod. 1983, 46, 576–581. doi:10.1021/np50028a027

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Vember, P. A.; Terent'eva, I. V. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1969, 5, 335–336. doi:10.1007/bf00595072

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bhajan, C.; Soulange, J. G.; Sanmukhiya, V. M. R.; Olędzki, R.; Harasym, J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10908. doi:10.3390/app131910908

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Dubey, A.; Ghosh, N.; Singh, R. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 2023, 27, 46–66. doi:10.25303/2710rjce046066

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Chalertpet, K.; Sangkheereeput, T.; Somjit, P.; Bankeeree, W.; Yanatatsaneejit, P. BMC Complementary Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 177. doi:10.1186/s12906-023-04003-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Macaev, F.; Stangaci, E.; Duc, D.; Duca, G. Utilizarea 1-metil-4-(N-metilaminobutil-4)-β-carbolinei in calitate de remediu antituberculos. Moldovan Patent MD4009B1, June 15, 2008.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Riaz, A.; Rasul, A.; Hussain, G.; Saadullah, M.; Rasool, B.; Sarfraz, I.; Masood, M.; Asrar, M.; Jabeen, F.; Sultana, T. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 33, 1233–1238. doi:10.36721/pjps.2020.33.3.sup.1233-1238.1

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Min, D. J.; Kim, S. J.; Hwang, J. S. Composition for external application containing PPARs activator from plant. WO Pat. Appl. WO066255A1, Oct 31, 2007.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Denisenko, P. P.; Vinogradova, T. V.; Semenov, A. A. Farmakol. Toksikol. (Moscow) 1988, 51, 50–53.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kireev, D.; Wigle, T. J.; Norris-Drouin, J.; Herold, J. M.; Janzen, W. P.; Frye, S. V. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 7625–7631. doi:10.1021/jm1007374

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Polledo, L.; García Marín, J. F.; Martínez-Fernández, B.; González, J.; Alonso, J.; Salceda, W.; García-Iglesias, M. J. J. Comp. Pathol. 2012, 147, 479–485. doi:10.1016/j.jcpa.2012.03.002

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Choi, G.; Hong, S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6166–6170. doi:10.1002/anie.201801524

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Krishnamurthy, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982, 23, 3315–3318. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)87603-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Terentjeva, I.; Lazurjevski, G.; Shirshova, T. I. Khim. Prir. Soedin. 1969, 5, 397–404.

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Aubry, C.; Jenkins, P. R.; Mahale, S.; Chaudhuri, B.; Maréchal, J.-D.; Sutcliffe, M. J. Chem. Commun. 2004, 1696–1697. doi:10.1039/b406076h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Redko, B.; Albeck, A.; Gellerman, G. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 2188–2191. doi:10.1039/c2nj40567a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ketcha, D. M.; Carpenter, K. P.; Zhou, Q. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 1318–1320. doi:10.1021/jo00003a077

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Coulton, S.; Gilchrist, T. L.; Graham, K. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 1193–1202. doi:10.1039/a800278i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prabakaran, K.; Zeller, M.; Szalay, P. S.; Rajendra Prasad, K. J. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2012, 49, 1302–1309. doi:10.1002/jhet.910

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bingul, M.; Arndt, G. M.; Marshall, G. M.; Black, D. S.; Cheung, B. B.; Kumar, N. Molecules 2021, 26, 5745. doi:10.3390/molecules26195745

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 37. | Choi, G.; Hong, S. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6166–6170. doi:10.1002/anie.201801524 |

| 38. | Krishnamurthy, S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982, 23, 3315–3318. doi:10.1016/s0040-4039(00)87603-0 |

| 39. | Terentjeva, I.; Lazurjevski, G.; Shirshova, T. I. Khim. Prir. Soedin. 1969, 5, 397–404. |

| 1. | Busqué, J.; Pedrosa, M. M.; Cabellos, B.; Muzquiz, M. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 1244–1254. doi:10.1007/s10886-010-9865-4 |

| 2. | Lazurjevski, G.; Terentjeva, I. Heterocycles 1976, 4, 1783–1816. doi:10.3987/r-1976-11-1783 |

| 3. | Terent'eva, I. Moldavii, Moldavsk. Tr. Inst. Khim. Akad. Nauk Kirg. SSR 1960, 21. |

| 2. | Lazurjevski, G.; Terentjeva, I. Heterocycles 1976, 4, 1783–1816. doi:10.3987/r-1976-11-1783 |

| 20. | Kuchkova, K.; Semenov, A.; Terentjeva, I. Khim. Geterotsikl. Soedin. 1970, 197. |

| 21. | Kuchkova, K.; Semenov, A.; Terentjeva, I. Acta Chim. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1971, 69, 367–371. |

| 28. | Bhajan, C.; Soulange, J. G.; Sanmukhiya, V. M. R.; Olędzki, R.; Harasym, J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10908. doi:10.3390/app131910908 |

| 29. | Dubey, A.; Ghosh, N.; Singh, R. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 2023, 27, 46–66. doi:10.25303/2710rjce046066 |

| 9. | Szabó, T.; Görür, F. L.; Horváth, S.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Synthesis 2022, 54, 3867–3873. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1737830 |

| 44. | Prabakaran, K.; Zeller, M.; Szalay, P. S.; Rajendra Prasad, K. J. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2012, 49, 1302–1309. doi:10.1002/jhet.910 |

| 45. | Bingul, M.; Arndt, G. M.; Marshall, G. M.; Black, D. S.; Cheung, B. B.; Kumar, N. Molecules 2021, 26, 5745. doi:10.3390/molecules26195745 |

| 4. | Szabó, T.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Molecules 2021, 26, 663. doi:10.3390/molecules26030663 |

| 5. | Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Földesi, T.; Grün, A.; Volk, B.; Keglevich, G.; Milen, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1953–1957. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.03.067 |

| 6. | Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 617–619. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.063 |

| 7. | Szabó, T.; Hazai, V.; Volk, B.; Simig, G.; Milen, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 1471–1475. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.04.044 |

| 8. | Szabó, T.; Dancsó, A.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 72–79. doi:10.1080/14786419.2019.1613401 |

| 9. | Szabó, T.; Görür, F. L.; Horváth, S.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Synthesis 2022, 54, 3867–3873. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1737830 |

| 10. | Pollák, P.; Garádi, Z.; Volk, B.; Dancsó, A.; Simig, G.; Milen, M. Nat. Prod. Res., in press. doi:10.1080/14786419.2024.2306600 |

| 11. | Szepesi Kovács, D.; Hajdu, I.; Mészáros, G.; Wittner, L.; Meszéna, D.; Tóth, E. Z.; Hegedűs, Z.; Ranđelović, I.; Tóvári, J.; Szabó, T.; Szilágyi, B.; Milen, M.; Keserű, G. M.; Ábrányi-Balogh, P. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 12802–12807. doi:10.1039/d1ra02132j |

| 12. | Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Dancsó, A.; Frigyes, D.; Volk, B.; Keglevich, G.; Milen, M. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 5711–5719. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.06.073 |

| 13. | Milen, M.; Hazai, L.; Kolonits, P.; Kalaus, G.; Szabó, L.; Gömöry, Á.; Szántay, C. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2005, 3, 118–136. doi:10.2478/bf02476243 |

| 14. | Milen, M.; Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Mucsi, Z.; Dancso, A.; Frigyes, D.; Pongo, L.; Keglevich, G. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013, 17, 1894–1902. doi:10.2174/13852728113179990035 |

| 15. | Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Volk, B.; Keglevich, G.; Milen, M. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2016, 1097, 48–60. doi:10.1016/j.comptc.2016.10.008 |

| 16. | Milen, M.; Ábrányi-Balogh, P. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2016, 52, 996–998. doi:10.1007/s10593-017-1997-9 |

| 17. | Milen, M.; Abranyi-Balogh, P.; Dancso, A.; Simig, G.; Keglevich, G. Lett. Org. Chem. 2010, 7, 377–382. doi:10.2174/157017810791514913 |

| 18. | Milen, M.; Hazai, L.; Kolonits, P.; Gömöry, Á.; Szántay, C.; Fekete, J. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2004, 27, 2921–2933. doi:10.1081/jlc-200030844 |

| 27. | Vember, P. A.; Terent'eva, I. V. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1969, 5, 335–336. doi:10.1007/bf00595072 |

| 24. | Marcu, G. A. T. Nauchn. Konf. Molodykh Uch. Mold., Biol. S-kh. Nauki. 1965, 243. |

| 25. | Iasnetsov, V. S.; Sizov, P. I. Farmakol. Toksikol. (Moscow) 1972, 35, 201–203. |

| 26. | Towers, G. H. N.; Abramowski, Z. J. Nat. Prod. 1983, 46, 576–581. doi:10.1021/np50028a027 |

| 40. | Aubry, C.; Jenkins, P. R.; Mahale, S.; Chaudhuri, B.; Maréchal, J.-D.; Sutcliffe, M. J. Chem. Commun. 2004, 1696–1697. doi:10.1039/b406076h |

| 41. | Redko, B.; Albeck, A.; Gellerman, G. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 2188–2191. doi:10.1039/c2nj40567a |

| 2. | Lazurjevski, G.; Terentjeva, I. Heterocycles 1976, 4, 1783–1816. doi:10.3987/r-1976-11-1783 |

| 2. | Lazurjevski, G.; Terentjeva, I. Heterocycles 1976, 4, 1783–1816. doi:10.3987/r-1976-11-1783 |

| 42. | Ketcha, D. M.; Carpenter, K. P.; Zhou, Q. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 1318–1320. doi:10.1021/jo00003a077 |

| 43. | Coulton, S.; Gilchrist, T. L.; Graham, K. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 1193–1202. doi:10.1039/a800278i |

| 23. | Müller, W. H.; Preuß, R.; Winterfeldt, E. Chem. Ber. 1977, 110, 2424–2432. doi:10.1002/cber.19771100703 |

| 39. | Terentjeva, I.; Lazurjevski, G.; Shirshova, T. I. Khim. Prir. Soedin. 1969, 5, 397–404. |

| 3. | Terent'eva, I. Moldavii, Moldavsk. Tr. Inst. Khim. Akad. Nauk Kirg. SSR 1960, 21. |

| 19. | Vember, P. A.; Terentjeva, I. Khim. Prir. Soedin. 1969, 5, 404–406. |

| 23. | Müller, W. H.; Preuß, R.; Winterfeldt, E. Chem. Ber. 1977, 110, 2424–2432. doi:10.1002/cber.19771100703 |

| 24. | Marcu, G. A. T. Nauchn. Konf. Molodykh Uch. Mold., Biol. S-kh. Nauki. 1965, 243. |

| 31. | Macaev, F.; Stangaci, E.; Duc, D.; Duca, G. Utilizarea 1-metil-4-(N-metilaminobutil-4)-β-carbolinei in calitate de remediu antituberculos. Moldovan Patent MD4009B1, June 15, 2008. |

| 30. | Chalertpet, K.; Sangkheereeput, T.; Somjit, P.; Bankeeree, W.; Yanatatsaneejit, P. BMC Complementary Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 177. doi:10.1186/s12906-023-04003-x |

| 28. | Bhajan, C.; Soulange, J. G.; Sanmukhiya, V. M. R.; Olędzki, R.; Harasym, J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10908. doi:10.3390/app131910908 |

| 9. | Szabó, T.; Görür, F. L.; Horváth, S.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Synthesis 2022, 54, 3867–3873. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1737830 |

| 9. | Szabó, T.; Görür, F. L.; Horváth, S.; Volk, B.; Milen, M. Synthesis 2022, 54, 3867–3873. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1737830 |

| 35. | Kireev, D.; Wigle, T. J.; Norris-Drouin, J.; Herold, J. M.; Janzen, W. P.; Frye, S. V. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 7625–7631. doi:10.1021/jm1007374 |

| 1. | Busqué, J.; Pedrosa, M. M.; Cabellos, B.; Muzquiz, M. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 1244–1254. doi:10.1007/s10886-010-9865-4 |

| 36. | Polledo, L.; García Marín, J. F.; Martínez-Fernández, B.; González, J.; Alonso, J.; Salceda, W.; García-Iglesias, M. J. J. Comp. Pathol. 2012, 147, 479–485. doi:10.1016/j.jcpa.2012.03.002 |

| 33. | Min, D. J.; Kim, S. J.; Hwang, J. S. Composition for external application containing PPARs activator from plant. WO Pat. Appl. WO066255A1, Oct 31, 2007. |

| 34. | Denisenko, P. P.; Vinogradova, T. V.; Semenov, A. A. Farmakol. Toksikol. (Moscow) 1988, 51, 50–53. |

| 32. | Riaz, A.; Rasul, A.; Hussain, G.; Saadullah, M.; Rasool, B.; Sarfraz, I.; Masood, M.; Asrar, M.; Jabeen, F.; Sultana, T. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 33, 1233–1238. doi:10.36721/pjps.2020.33.3.sup.1233-1238.1 |

| 29. | Dubey, A.; Ghosh, N.; Singh, R. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 2023, 27, 46–66. doi:10.25303/2710rjce046066 |

© 2025 Batizi et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.