Abstract

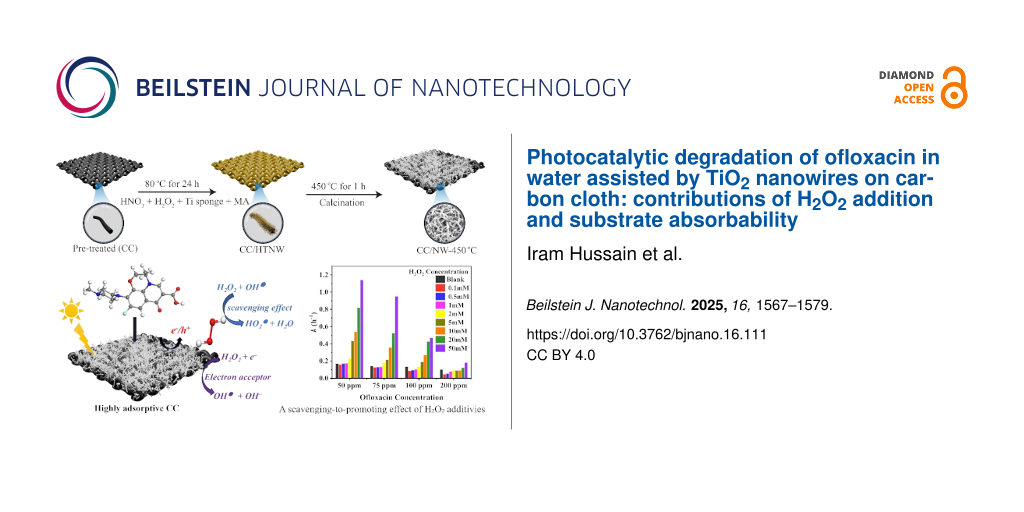

Vertically aligned TiO2 nanowires demonstrate exceptional photoactivity owing to their high specific surface area and improved charge separation; however, their unsatisfactory interaction with target contaminants diminishes photocatalytic degradation efficiency in water. Here, we present a mild solution method to precipitate anatase TiO2 nanowire arrays, measuring 1.5 μm in thickness, over carbon cloth to ensure substantial interactions with target pollutants and, in turn, a superior photoactivity. Compared to TiO2 nanowire arrays grown on metallic Ti substrates, TiO2 nanowires supported on carbon cloth substrates demonstrate markedly superior efficiency in the photocatalytic degradation of ofloxacin (OFL) molecules in water when exposed to UV light. The TiO2 nanowires remove 90–97% OFL in water with a high initial concentration of 50 ppm in 6 h under UV light irradiation for up to six cycles. The contributions of the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) additive were also studied. An enhanced efficiency could be achieved only when the H2O2 in water reaches a critical amount, below which a negative effect is noted. This investigation demonstrates the potential of improving the photoactivity of one-dimensional TiO2 nanostructures by utilizing a highly adsorptive substrate, which can help mitigate the effects of hazardous materials in water.

Introduction

Drug pollution in natural environments has become an increasingly serious issue as a result of the wide applications of drugs in the diagnosis and treatment of human diseases, anti-epidemic disinfection, aquaculture additives, and veterinary drugs [1,2]. Ofloxacin (OFL) is a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone antibiotic widely used in clinical treatments for various bacterial infections [3]. After administration, OFL is not fully metabolized and is primarily excreted through urine, leading to its presence in wastewater and contamination of aquatic environments. Studies have reported OFL concentrations in surface waters ranging from 0.05 to 17.7 μg/L, posing a potential risk to aquatic organisms and disrupting ecosystem balance [4,5]. Therefore, OFL removal from water is an important issue in environmental science and engineering.

Conventional treatment approaches, including adsorption, membrane separation, and biological methods, are largely inadequate for antibiotics such as OFL [6,7]. This limitation highlights the need for advanced oxidation processes, with a particular emphasis on TiO2-based photocatalysis [8]. However, TiO2 as a sole component presents challenges partly due to the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, which significantly reduces its photocatalytic efficiency and practical applicability [9,10].

Recent advancements have focused on TiO2 photocatalysts supported on porous materials, such as carbon-based adsorbents. These innovations help to slow down electron–hole recombination, broaden light absorption, and enhance surface adsorption sites [11]. Cao et al. synthesized TiO2 nanowires on reduced graphene oxide (rGO) through a solvothermal method, which improved active sites and facilitated interfacial charge separation [12]. Activated carbon effectively supports TiO2, enhancing adsorption capacity and loading, which directly impacts photocatalytic efficiency [13]. In contrast to rGO or activated carbon granules, employing carbon cloth as substrates mitigates the aggregation issues and simplifies the separation and recovery of photocatalysts within a slurry system. TiO2 nanowires are known for their significantly high surface area and are important for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical applications. Template-mediated methods such as sol–gel deposition, electrophoretic deposition, and electrochemical deposition are extensively utilized for the synthesis of TiO2 nanowire arrays, owing to their advantageous physical properties and varied applications [14,15].

Our previous study accomplished the precipitation of TiO2 nanowire arrays, with controlled film thickness of 1.5–4.5 μm, on concurrently activated carbon cloth substrates. The composite film exhibited a high efficiency towards removal of rhodamine B and sulfosalicylic acid in water under UV light illumination, mainly thanks to the highly adsorptive substrate [16]. In the current investigation, we extend the application to drug pollution treatments with OFL as a model molecule. Since H2O2 produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), which promote the oxidation and degradation of OFL, H2O2 was introduced into the system to increase the photocatalytic efficiency, and the impacts of its concentration were studied. The higher production of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) in the degradation of organic pollutants enhances the degradation efficiency of OFL. The TiO2 nanowires exhibited significant photodegradation of OFL in water with a high initial concentration range of 50–200 ppm, which is much higher than that of 10–20 ppm adopted by most studies, highlighting the advantages of the one-dimensional TiO2 material on an adsorptive substrate as a photocatalyst.

Experimental

Materials and reagents

Carbon cloth with a purity of 99.8% was provided by Shanghai Hesen Industry Company Limited, China. Hydrogen peroxide (30 wt %, AR), HNO3 (65 wt %, AR), and ethyl alcohol (99.7 wt %, AR) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China. Melamine (99 wt %, AR) was purchased from Aladdin, China. PHILPS Lighting Investment Company Limited, China, provided the UV lamp. All chemicals were used without further purification. Deionized water was used for all the experiments.

Synthesis of TiO2 nanowires on carbon cloth

The synthesis follows basically our previous study but on a larger scale [16]. In brief, a 5 cm × 10 cm piece of carbon cloth (CC) underwent three cleaning cycles using ethyl alcohol and deionized water alternately in an ultrasonic bath, followed by drying at 60 °C. After that, it was immersed in 200 mL of a 30 wt % H2O2 solution, containing 60 mg of melamine, 4 mL of 65 wt % HNO3, and 1 g of titanium sponge, at 80 °C for 24 h to facilitate the precipitation of hydrogen titanate nanowires. Final calcination in air at 450 °C for 1 h was conducted to decompose titanates into anatase TiO2 and simultaneously activate the carbon cloth to achieve a high specific surface area [17]. The carbon cloth on which TiO2 nanowire arrays were precipitated is referred to as CC/NW-450°C. For comparisons, anatase TiO2 nanowire arrays on metallic Ti foils were synthesized according to previous reports [18] and designated as Ti/NW-450 °C. Commercial Degussa P25 TiO2 nanoparticles were also loaded on Ti substrates 5 × 10 × 0.01 cm3 in size by repetitive dip coating in an ethanolic P25 slurry and drying. The P25 loading was ca. 50.0 mg (≈1.0 mg/cm2), nearly the same as that of the TiO2 nanowires on carbon cloth.

Characterizations

The morphologies were analyzed using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Zeiss Germany Sigma 300) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) conducted with a JEM-2100 microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan). Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) elemental mapping was performed using the FESEM system to examine the distribution of Ti and O on the carbon cloth substrate. X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were conducted using a SmartLab diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation) with Cu Kα radiation, operating at 40 kV and 35 mA. Raman spectra were obtained using an Alpha300R UV system (WITec, Germany) equipped with a TEM00 laser at a wavelength of 532 nm. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterizations were conducted using a Kratos AXIS Ultura DLD system (Kratos, UK), and the binding energies were calibrated to C 1s = 284.8 eV. The specific surface area and pore size were analyzed using low-temperature N2 adsorption–desorption measurements conducted with an ASAP 2460 (USA). The absorption spectrum of the sample was acquired through UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-3150, Shimadzu, Japan). The concentration of OFL was determined using a Nexera LC-40D XR ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (SHIMADZU, Japan). A Pyris 1 TGA instrument (USA) was used to carry out the thermogravimetric (TG) investigations of as-precipitated nanowires in air at a heating rate of 10 K·min−1 from room temperature to 500 °C. The static water contact angles were measured using a goniometer (OCA 11, DataPhysics Instruments GmbH, Filderstadt, Germany) following the standard sessile drop method. The measurements were performed at room temperature. A TOC-L CPH analyzer (SHIMADZU, Japan) was used to detect total organic carbon (TOC).

Photocatalytic activity for OFL removal

The photocatalytic activity was evaluated through the photodegradation of 50 mL aqueous solutions of OFL at initial concentrations of 50, 75, 100, and 200 ppm, utilizing carbon cloth coated with nanowires with a nominal area of 5 cm × 10 cm in a Pyrex reactor. A UV lamp with a power of 18 W was positioned 5.5 cm above the fluid to provide irradiation. The average UV intensity at the solution level was approximately 5.0 mW·cm−2, measured using an irradiance meter (Model UV-A, Beijing Normal University). The solution was maintained in darkness, and the UV light was activated following the establishment of a dark adsorption–desorption equilibrium for three hours. The degradation experiments were repeated in triplicate to ensure statistical reliability. Error bars represent the standard deviation calculated from these repeated experiments.

The adsorption removal ratio of OFL was calculated using Equation 1:

where c0 represents the initial concentration of OFL (ppm), and cads denotes the concentration of OFL after the adsorption (ppm). The photodegradation ratio of OFL was determined using Equation 2:

where, cads represents the concentration of OFL after the dark adsorption (ppm), while ct denotes the concentration of OFL at time t during the photodegradation (ppm). The reaction rate constant (k) of the OFL degradation was assessed using the pseudo-first-order kinetic model, as determined by Equation 3:

The concentration of OFL was assessed using high-performance liquid chromatography with a C18 column maintained at 30 °C. The UV–vis detector was calibrated to a wavelength of 292 nm. The mobile phase consisted of a 15:85 ratio of methanol to 0.8% acetic acid in ultrapure water, with a flow rate set at 1.0 mL·min−1 and an injection volume of 10 μL. Every hour, 0.2 mL of OFL solution was sampled. The photocurrent was tested using a three-electrode system on an electrochemical workstation (CHI600E, Shanghai Chenhua), in which the carbon cloth (2 cm × 2 cm in size) was taken as working electrode, the Pt electrode as counter electrode (3 cm × 3 cm in size), and a saturated calomel electrode as reference electrode; the electrolyte is 0.5 mol/L aqueous Na2SO4 solution. No bias potential was applied for the photocurrent evaluations.

Results and Discussion

Microstructure and morphology of photocatalysts

Figure 1a shows schematically the synthesis of TiO2 nanowires on an activated carbon cloth substrate. When the carbon cloth is immersed in the Ti–H2O2 precursor solution maintained at 80 °C, first, the carbon cloth surface is activated, and, second, the hydrogen titanate nanowires precipitate. In the acidic medium, the reaction between metallic Ti sponge and hydrogen peroxide produces titanium hydroxide species in solution. Once the concentration of these species reaches saturation, hydrogen titanate nanowires nucleate and grow directly on the carbon cloth substrate via a heterogeneous nucleation mechanism [19,20]. Figure S1 in Supporting Information File 1 shows the homogeneous precipitation of hydrogen titanate nanowires on the carbon cloth. Subsequent calcination in air at 450 °C transformed the hydrogen titanate structures into anatase TiO2 nanowires, while largely retaining their original one-dimensional morphology. Figure 1b–d presents representative FESEM images of the resulting TiO2 nanowires uniformly deposited on the carbon cloth substrate. Each carbon fiber is evenly coated with quasi-aligned nanowires that radiate outward, forming a net-like architecture. After reacting in the Ti–H2O2 aqueous system at 80 °C for 24 h, the synthesized nanowire layer reaches an approximate thickness of 1.5 μm, covering the substrate homogeneously. Additionally, EDX mapping analysis (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S2) confirms that Ti and O are homogeneously distributed over the carbon cloth fibers, supporting the uniform and successful growth of TiO2 nanowires. The successful formation of TiO2 nanowires is further confirmed by TEM analysis. As shown in Figure 1e,f, the CC/NW-450 °C sample displays a distinct net-like network of nanowires. The corresponding selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern reveals clear diffraction rings attributable to anatase and minor brookite TiO2 phases. Additionally, the HRTEM image (Figure 1f) shows well-defined lattice fringes with a spacing of approximately 0.35 nm, which corresponds to the (101) crystal plane of anatase TiO2.

![[2190-4286-16-111-1]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-1.jpg?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: (a) The Ti–H2O2 interaction approach to precipitate TiO2 nanowire arrays on carbon cloth. (b–d) FESEM images of TiO2 nanowires grown on carbon cloth at different magnifications. (e) TEM, (f) HRTEM images, and (g) the corresponding SAED pattern of the CC/NW-450 °C.

Figure 1: (a) The Ti–H2O2 interaction approach to precipitate TiO2 nanowire arrays on carbon cloth. (b–d) FES...

Figure 2a shows the XRD patterns of hydrogen titanate nanowires precipitated on carbon cloth (CC/HTNW) and of the sample after air calcination (CC/NW-450 °C). Except for two broad XRD peaks arising from the carbon substrate, a peak located at ca. 8.5° can be seen for the CC/HTNW, which corresponds to hydrogen titanate H2Ti5O11·3H2O (JCPDS card no. 44-0130). The TiO2 nanowires are predominantly in the anatase phase, as indicated by characteristic anatase peaks, such as the (101), (004), (200), and (105) reflections at 2θ = 25.3°, 37.8°, 48.0°, and 54.0°, respectively (JCPDS card no. 21-1272). The Raman spectra in Figure 2b are in accordance with the XRD analysis in phase composition. The CC/NW-450 °C spectrum displays prominent peaks at 146, 195, 287, 395, 516, and 637 cm−1, corresponding to the Eg, A1g, B1g, B1g, (A1g + B1g), and Eg modes of the anatase phase, respectively [21-23]. Characteristic peaks corresponding to brookite TiO2 can also be seen in the XRD pattern and the Raman spectrum of CC/NW-450 °C. The Raman spectrum in Figure 2b also indicates the degree of disorder in the carbon cloth by the ratio (ID/IG) of the disorder-induced (D) band (≈1350 cm−1) and the graphite (G) band (≈1582 cm−1) [17]. The increasing ratio suggests an increasing surface disordering of the carbon cloth after calcination, which contributes to the high adsorption capacity toward the target molecules.

![[2190-4286-16-111-2]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: (a) XRD patterns and (b) Raman spectra of hydrogen titanate nanowires (CC/HTNW) and TiO2 nanowires (CC/NW-450 °C) grown on carbon cloth.

Figure 2: (a) XRD patterns and (b) Raman spectra of hydrogen titanate nanowires (CC/HTNW) and TiO2 nanowires ...

Figure 3a illustrates the UV–vis diffuse absorbance spectrum of the CC/HTNW and CC/NW-450 °C. The black carbon cloth absorbs light in the wavelength range of 250–800 nm, and the UV adsorption edge can be seen clearly after TiO2 precipitations. According to the Kubelka–Munk formula, assuming an indirect transition between valence and conduction bands [24], the bandgap for the CC/NW-450 °C is evaluated to be 2.97 eV (Figure 3a inset). This value is smaller than the bandgap of 3.2 eV for anatase TiO2, which can be attributed to the strong interaction between TiO2 and the carbon cloth, which may induce localized states within the bandgap and potentially introduce defects into the TiO2 lattice.

![[2190-4286-16-111-3]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-3.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 3: (a) UV–vis diffuse absorbance spectrum of the CC/NW-450 °C. The inset shows the replotting of (a) in (αhν)1/2 ~ hν coordinates to evaluate the bandgap of CC/NW-450 °C. (b) Low-temperature nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of CC/NW-450 °C. The inset shows the corresponding pore size distribution curve.

Figure 3: (a) UV–vis diffuse absorbance spectrum of the CC/NW-450 °C. The inset shows the replotting of (a) i...

Figure 3b shows the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of the TiO2 nanowires on carbon cloth at 77 K. The adsorption isotherm exhibits a type-IV profile with an H3 hysteresis loop, indicative of mesoporous structures with slit-like pores. This is further corroborated by the pore size distribution, which shows a sharp peak at approximately 4.0 nm, suggesting a uniform pore size. The corresponding pore size distribution curve (Figure 3b, inset) indicates a mesoporous structure. Before calcination, the BET surface area of the titanate on carbon cloth was found to be 3.9 m2·g−1 and a pore volume of 0.025 cm3·g−1, indicating limited surface area and porosity. The average pore diameter was 3.83 nm, suggesting the presence of mesopores (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S2). Note here that the carbon cloth substrate was included when evaluating the BET specific surface area. After calcination at 450 °C, the BET surface area increased remarkably to 289.9 m2·g−1, reflecting a significant enhancement in surface properties because of the activation of the carbon cloth via simple air calcination [17]. The pore volume is 0.047 cm3·g−1, with an average pore diameter of 3.82 nm.

TG analysis has been carried out, and the results are shown in Supporting Information File 1, Figure S4. The weight loss of CC/NW-450 °C is 2.16 wt %, which can be attributed to the physically adsorbed water. For CC/HTNW, 9.62 wt % weight loss is recorded, which is a result of additional water evaporation upon the decomposition of hydrogen titanate, according to Equation 4.

The surface composition and oxidation states of TiO2 nanowires on carbon cloth (CC/NW-450 °C) and CC/HTNW were examined by XPS (Figure 4). The survey spectrum confirms the presence of Ti, O, and C (Figure 4a) in both samples. The C 1s spectrum shows a peak at 284.8 eV, corresponding to adventitious carbon, which was used as the reference for binding energy calibration. Additional peaks at higher binding energies (286–288 eV) are attributed to oxygen-containing functional groups (C–O and C=O), indicating partial oxidation of the carbon surface. The Ti 2p spectra (Figure 4d) show characteristic peaks for CC/HTNW, with Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 peaks appearing at 458 and 463 eV, respectively, while for CC/NW-450 °C, these peaks slightly shift to 459 and 464 eV, respectively. The spin–orbit splitting remains ≈5.4 eV confirming the Ti4+ state from the lattice [25]. The O 1s spectra (Figure 4c) show significant differences between the two samples. For CC/HTNW, two peaks are observed at 530 and 532 eV, corresponding to lattice oxygen and surface hydroxyl groups (–OH), respectively. After calcination (CC/NW-450 °C), the relative intensity of the hydroxyl peak decreases, and the peaks shift slightly (O–Ti at 529.7 eV and –OH at 531 eV), indicating a reduction in surface –OH groups due to dehydration and phase transformation from hydrogen titanate to anatase TiO2. Based on the area underneath the corresponding O 1s XPS peak, the content of hydroxyl groups in CC/HTNW is evaluated to be ca. 52%, which reduced to approximately 16% after the final air calcination, suggesting abundant residual surface oxygen vacancies in CC/NW-450 °C. These vacancies are beneficial for enhancing photocatalytic activity [26,27].

![[2190-4286-16-111-4]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-4.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 4: XPS spectra of CC/NW-450 °C and CC/HTNW. (a) Survey spectra and detailed XPS spectra of (b) C 1s, (c) O 1s, and (d) Ti 2p.

Figure 4: XPS spectra of CC/NW-450 °C and CC/HTNW. (a) Survey spectra and detailed XPS spectra of (b) C 1s, (...

Photocatalytic activity for OFL removal and materials durability

The photocatalytic activities of the carbon cloth-supported TiO2 nanowires (CC/NW-450 °C) were assessed by monitoring the degradation of various concentrations of OFL aqueous solutions under UV light radiation, as shown in Figure 5a. The corresponding reaction rate constants are shown in Figure 5b. Not surprisingly, the photocatalytic activity decreases with increasing OFL initial concentration (50, 75, 100, and 200 ppm), with the reaction rate constant declining (0.169, 0.142, 0.135, and 0.103 h−1, respectively). The high photocatalytic performance at lower OFL concentrations is attributed to the more efficient utilization of active sites and better light penetration in the solution. The TOC removal efficiency of the carbon cloth-supported TiO2 nanowires (CC/NW-450 °C) was also evaluated, as shown in Figure 5c. The TOC values decreased over time for all tested concentrations of OFL (50–200 ppm), indicating progressive mineralization of the pollutant. At 50 ppm, the TOC decreased from 51.04 to 17.31 mg·L−1 after 12 h, corresponding to a 66% reduction. At 200 ppm, the TOC decreased from 205.1 to 30.25 mg·L−1 (12 h), achieving an 85% reduction, which demonstrates effective mineralization even at high pollutant loads. This trend aligns with the photocatalytic degradation kinetics (Figure 5b), where the reaction rate constant was the highest at lower concentrations (0.169 h−1 for 50 ppm vs 0.103 h−1 for 200 ppm). While the degradation rate was higher at lower concentrations due to efficient light penetration and active site utilization, the absolute TOC removal was significantly higher at 200 ppm, highlighting the catalyst’s capacity to mineralize large organic loads under optimized conditions.

![[2190-4286-16-111-5]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-5.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 5: (a) Photocatalytic degradation of ofloxacin in water with various initial concentrations (50, 75, 100, and 200 ppm) assisted by CC/NW-450 °C under UV irradiation. (b) The corresponding fit curves assume pseudo-first-order reaction kinetics. (c) TOC removal after 6 and 12 h. (d) Cycling performance. Initial OFL concentration: 50 ppm.

Figure 5: (a) Photocatalytic degradation of ofloxacin in water with various initial concentrations (50, 75, 1...

The reusability of the CC/NW-450 °C photocatalyst was examined through repetitive degradations of 50 ppm OFL solution under UV light irradiation (Figure 5d). Unlike the experiment in Figure 5a, which included a dark adsorption (from −3 to 0 h) allowing OFL to adsorb onto the photocatalyst before light exposure, the cycling experiments in Figure 5d were conducted under UV light without a prior dark adsorption. This difference in experimental conditions accounts for the variation in degradation profiles between the two figures. After 6 h of irradiation, approximately 96.9% OFL degradation was achieved on the first run. This suggests that dynamic adsorption and simultaneous photocatalytic degradation of target molecules contribute to a higher efficiency for pollutant removal. The photocatalytic efficiency remained consistently high throughout the next 5 runs, with degradation efficiencies between 90% and 95% after 6 h. The fact that the photocatalyst retained over 90% of its efficiency even after 6 cycles demonstrates the stability of the CC/NW-450 °C photocatalyst. SEM and XRD data of the catalyst after the recycling experiment are shown in Figure S8 in Supporting Information File 1, from which no remarkable change can be seen because of its high structural stability. High photocatalytic activity over multiple cycles, along with simple, low-cost, and stable operation, are the key parameters for their promising applications in practical wastewater treatment, in which the frequent replacement or regeneration of the catalyst must be avoided.

Influence of the hydrogen peroxide additive

Figure 6a–d presents the photocatalytic degradation curves of OFL with various concentrations of 50, 75, 100, and 200 ppm, assisted by the carbon cloth-supported TiO2 nanowires and in the presence of H2O2 with various concentrations. The corresponding reaction rate constants are summarized in Figure 7a. The reaction rate constants for OFL in water with initial concentrations of 50 and 75 ppm increased gradually with increasing H2O2 additives. After 6 h, the removal is approximately 85% and 76% for 50 and 75 ppm OFL, respectively, in the presence of 10 mM H2O2. More complicated phenomena are observed for OFL in water with a higher initial concentration of 100 and 200 ppm. Upon increasing the H2O2 concentration from 0.1 to 5 mM, the reaction rate constant vs H2O2 concentration curve exhibits a “U” shape, which suggests that there is a critical H2O2 concentration, only beyond which the H2O2 additive contributes to OFL degradation. This dual behavior can be attributed to competing roles of H2O2 in advanced oxidation processes. At sub-critical concentrations, H2O2 may act as a scavenger of hydroxyl radicals (OH•) or holes (h+), reducing their availability for OFL degradation, as explained by (Equation 5):

![[2190-4286-16-111-6]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-6.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 6: Photocatalytic degradation of various ofloxacin concentrations of (a) 50 ppm, (b) 75 ppm, (c) 100 ppm, and (d) 200 ppm in the presence of different concentrations (0.1–50 mM) of hydrogen peroxide. Note here that the error bars were provided only for selected curves.

Figure 6: Photocatalytic degradation of various ofloxacin concentrations of (a) 50 ppm, (b) 75 ppm, (c) 100 p...

Above the critical concentration, H2O2 primarily serves as an electron acceptor (Equations 6 and 7), generating additional OH• radicals via reactions with superoxide radicals (O2•–) or photogenerated electrons (e–) [28], demonstrated by the subsequent reactions:

These reactions demonstrate that H2O2 acts as an electron acceptor, leading to the formation of OH•; the resulting OH• radicals drive OFL degradation, explaining the enhanced reaction rates at higher H2O2 concentrations [29]. The scavenging-to-promotion transition underscores the need to optimize H2O2 dosing, particularly for high pollutant loads (e.g., 100–200 ppm OFL), where excess H2O2 initially suppresses degradation until sufficient radicals are generated.

![[2190-4286-16-111-7]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-7.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 7: (a) Reaction rate constants of ofloxacin degradations assisted with CC/NW-450 °C and in the presence of H2O2 with various concentrations. The initial ofloxacin concentrations are 50, 75, 100, and 200 ppm. (b) Transient photocurrent responses of the CC/NW-450 °C under periodic light on/off cycles in electrolytes with different H2O2 concentrations. Initial OFL concentration: 50 ppm.

Figure 7: (a) Reaction rate constants of ofloxacin degradations assisted with CC/NW-450 °C and in the presenc...

In the current investigation, we note that H2O2 beyond a critical concentration may be necessary to generate sufficient OH• radicals for effective degradations of OFL with a high initial concentration, say, 100 ppm and 200 ppm. The photocurrent response in Figure 7b increases with increasing H2O2 concentrations in the 0.5 M Na2SO4 electrolyte, because H2O2 acts as an electron acceptor, facilitating charge separation and the generation of ROS, such as OH• radicals, which directly contribute to the degradation process [30]. The effect of H2O2 concentration on photocatalytic OFL degradation in the presence of hydroxyl radical scavengers was investigated using n-butanol as a probe molecule (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S6). In these experiments, 10 mM n-butanol was added to serve as an •OH scavenger to evaluate the role of hydroxyl radicals in the degradation process. The results demonstrate a clear concentration-dependent effect of H2O2 on OFL removal efficiency. At low H2O2 concentrations (5 mM), OFL degradation was comparable to the catalyst alone, indicating that the limited •OH radical generation was effectively quenched by n-butanol. As H2O2 concentration increased to 10 mM, a slight improvement in degradation was observed, suggesting that •OH radical production began to exceed the scavenging capacity of n-butanol. The most significant enhancement occurred at 50 mM H2O2, where OFL degradation reached approximately 60% after 3 h, demonstrating that high H2O2 concentrations can overcome the inhibitory effect of radical scavengers through increased ROS generation. This trend confirms the dominant role of •OH radicals in the photocatalytic degradation mechanism.

Supporting Information File 1, Figure S7 explores the effect of the pH value on the OFL degradation efficiency. The highest degradation occurs at a slightly alkaline pH (pH 8), where ROS generation and pollutant adsorption onto TiO2 are the most favorable. Both strong acidic (pH 2) and highly basic (pH 12) conditions reduce the degradation efficiency, likely due to reduced ROS stability or altered surface interactions. It demonstrates that the carbon cloth-supported TiO2 nanowires are capable of functioning in wastewater with a wide pH range.

The active radical species produced during photocatalytic OFL degradations were clarified using trapping studies. n-Butanol, potassium iodide (KI), and potassium bromate (KBrO3) were employed as quenchers for hydroxyl radicals [31], holes [32], and e− [33], respectively. Figure 8 illustrates that n-butanol reduced the OFL removal of 50 ppm to 30% over 3 h, indicating a significant supporting function of singlet hydroxyl radicals. The introduction of KI further reduced the OFL removal to 13% after 3 h of reaction, underscoring the pivotal function of holes as the principal reactive species accountable for the OFL degradation in our system. The introduction of KBrO3 resulted in a relatively modest reduction in the removal to 41%, suggesting that the involvement of e− is minor in the process. These results indicate that the photocatalytic degradation mechanism is predominantly governed by photogenerated holes, followed by hydroxyl radicals.

TiO2 nanowires generate electron–hole pairs upon excitation by UV light (Equation 8). The photogenerated holes are the predominant reactive species. These holes can directly oxidize OFL molecules or water molecules adsorbed on the surface, resulting in the formation of hydroxyl radicals. Holes can oxidize hydroxide ions to generate hydroxyl radicals (Equation 10), which, although secondary, significantly contribute to the degradation process. The photogenerated electrons may react with oxygen molecules in the solution to produce superoxide radicals (Equation 10). Nonetheless, their role is insignificant in the current investigation. OFL may be compromised by those reactive species (Equations 12–14). The potential photocatalytic degradation mechanisms of OFL are thus delineated as follows and demonstrated schematically in Figure 8b.

![[2190-4286-16-111-8]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-8.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 8: OFL degradations assisted by TiO2 nanowires on carbon cloth with different radical trapping agents. The initial concentration is 50 ppm. (b) Radical pathway of the photocatalytic OFL degradation in the presence of CC/NW-450 °C.

Figure 8: OFL degradations assisted by TiO2 nanowires on carbon cloth with different radical trapping agents....

The effects of the substrate with high adsorption capability

The contact angle measurements in Supporting Information File 1, Figure S9 reveal distinct differences in surface wettability among the samples. The pristine carbon cloth shows a high contact angle of approximately 138.9°, indicating strong hydrophobicity (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S9b). Remarkably, the CC/NW-450 °C composite exhibits a contact angle of 0° (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S9c), showing complete wettability. This significant enhancement in hydrophilicity is attributed to the high surface roughness and porous hydrophilic nanowire architecture formed on the carbon cloth, which improves water spreading and facilitates the adsorption of aqueous pollutants during photocatalytic degradation [34]. The Ti foil covered with TiO2 nanowires (TiP/NW-450 °C) exhibits a contact angle of around 62.4° (Supporting Information File 1, Figure S9a), reflecting a moderate hydrophilicity. Figure 9a shows the photocatalytic degradation curves and the corresponding fit results assuming a pseudo-first-order reaction for OFL with an initial concentration of 50 ppm and in the presence of TiO2 nanowires quasi-aligned on carbon cloth and metallic Ti substrates. The efficiency is also compared with the benchmark commercial P25 TiO2 nanoparticles deposited on a Ti substrate. All thin films were controlled to be of almost identical film thickness for a reasonable comparison. Both nanowire samples exhibit a photoactivity superior to that of the benchmark P25 when utilized in the form of thin films. It also indicates that the highly adsorptive carbon cloth substrate, as suggested by the dark adsorption curves in Figure 9b, contributes to the photoactivity of TiO2 nanowires. This fact indicates a synergistic effect resulting from substrate adsorption and TiO2 photodegradation. The synergistic effect may involve (1) carbon cloth possessing a substantial specific surface area and surface mesopores, which offers numerous adsorption sites, thereby concentrating solute molecules near the surface of thin films [13], (2) the transfer of photogenerated electrons from TiO2 to the conductive carbon cloth, facilitating the separation of photogenerated electron–hole pairs [13,35], and (3) the substrate’s fibrous structure significantly enhancing the effective contact area and preventing the aggregation of nanowires.

![[2190-4286-16-111-9]](/bjnano/content/figures/2190-4286-16-111-9.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 9: (a) Photocatalytic degradation curves of 50 ppm ofloxacin assisted by TiO2 nanowires on carbon cloth (CC/NW-450 °C), TiO2 nanowires on Ti plate (Tip/NW-450 °C), and the benchmark P25 on Ti plate (P25). (b) The corresponding fit results assuming pseudo-first-order reaction kinetics.

Figure 9: (a) Photocatalytic degradation curves of 50 ppm ofloxacin assisted by TiO2 nanowires on carbon clot...

Conclusion

TiO2 nanowire thin films of ca. 1.5 μm in thickness were precipitated on carbon cloth via Ti–H2O2 interaction, followed by a subsequent calcination in air. The synthetic process also activated the carbon cloth, significantly increasing the specific surface area to 289.9 m2·g−1. The TiO2 nanowires supported on carbon cloth demonstrated excellent efficiency for degradation of ofloxacin in water with high initial concentrations of 50–200 ppm. Importantly, introducing H2O2 beyond a critical concentration further improved degradation efficiency by facilitating generation of reactive oxygen species, especially hydroxyl radicals. Trapping experiments suggest that the photogenerated holes were the primary factor in the photocatalytic mechanism, while the cooperative effects of hydroxyl radicals facilitated the process. A scavenging-to-promoting transition was thus noted concerning the effects of the H2O2 additives. The TiO2 nanowire arrays on carbon cloth exhibited an improved photoactivity compared to the counterparts on metallic Ti foils, which can be attributed to a synergetic effect resulting from a greatly increased adsorption capacity and the considerable photodegradation efficiency by TiO2 nanowires. Significant TOC removal (85%) was recorded for ofloxacin in water with a high concentration of 200 ppm, suggesting the high adsorption capacity and probably a deep mineralization capacity of the thin film photocatalyst developed in the current investigation. This work represents a new promising strategy to tackle emerging contaminants and could lead to the advancement of cutting-edge materials for environmental remediation.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Additional figures. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.3 MB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

Data generated and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Malmqvist, E.; Fumagalli, D.; Munthe, C.; Larsson, D. G. J. Public Health Ethics 2023, 16, 152–164. doi:10.1093/phe/phad012

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Larsson, D. G. J. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B 2014, 369, 20130571. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0571

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Enna, S. J.; Bylund, D. B., Eds. xPharm: the comprehensive pharmacology reference; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2008.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deng, Y.; Debognies, A.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 244, 106084. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2022.106084

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, N.; Jin, X.; Feng, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, F.; Johnson, A. C.; Xiao, H.; Hollert, H.; Giesy, J. P. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105454. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2019.105454

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rosario-Ortiz, F. L.; Wert, E. C.; Snyder, S. A. Water Res. 2010, 44, 1440–1448. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2009.10.031

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Luo, C.; Ma, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Wu, D. Water Res. 2015, 80, 99–108. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2015.05.019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Guo, Q.; Zhou, C.; Ma, Z.; Yang, X. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2019, 31, 1901997. doi:10.1002/adma.201901997

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2557–2567. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.12.086

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Reghunath, S.; Pinheiro, D.; KR, S. D. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 3, 100063. doi:10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100063

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yue, Y.; Yue, X.; Tang, X.; Han, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Du, C. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30817. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30817

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cao, X.; Tian, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, W.; Tian, C.; Fu, H. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 4366–4374. doi:10.1039/c3ta14272h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, G. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 1061–1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.04.058

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Lin, Y. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 1246–1248. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2007.08.021

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lv, X.; Zhang, H.; Chang, H. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 789–795. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.07.059

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, J.-M.; Zhao, Q.-E. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 527, 146779. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146779

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Gu, Y.-J.; Wen, W.; Wu, J.-M. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 21078–21086. doi:10.1039/c8ta07561a

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Wu, J.-M.; Xue, H.-X. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 2139–2143. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03153.x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Q.-E.; Wen, W.; Xia, Y.; Wu, J.-M. Thin Solid Films 2018, 648, 103–107. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2018.01.004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, Q.-E.; Wen, W.; Xia, Y.; Wu, J.-M. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 124, 192–198. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.09.016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sekiya, T.; Ohta, S.; Kamei, S.; Hanakawa, M.; Kurita, S. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2001, 62, 717–721. doi:10.1016/s0022-3697(00)00229-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cao, S.; Chan, T.-S.; Lu, Y.-R.; Shi, X.; Fu, B.; Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, K.; Alzuabi, S.; Cheng, P.; Liu, M.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Piao, L. Nano Energy 2020, 67, 104287. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104287

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Challagulla, S.; Tarafder, K.; Ganesan, R.; Roy, S. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8783. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08599-2

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Madhusudan Reddy, K.; Manorama, S. V.; Ramachandra Reddy, A. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003, 78, 239–245. doi:10.1016/s0254-0584(02)00343-7

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Du, X.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; Han, B.; Su, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Li, M.; Tang, H.; Li, G.; Qiao, B. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5811. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19484-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xing, H.; Wen, W.; Wu, J.-M. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2019, 382, 111958. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.111958

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, H. Appl. Catal., B 2013, 134–135, 198–204. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.01.006

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Saha, D.; Desipio, M. M.; Hoinkis, T. J.; Smeltz, E. J.; Thorpe, R.; Hensley, D. K.; Fischer-Drowos, S. G.; Chen, J. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4927–4936. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2018.07.030

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barakat, M. A.; Tseng, J. M.; Huang, C. P. Appl. Catal., B 2005, 59, 99–104. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.01.004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Harun, N.; Sheng, C. K.; Sabri, M. G. M.; Dagang, A. N.; Salleh, H. J. Optoelectron. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 12, 9–15. doi:10.15251/jobm.2020.121.9

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Linetsky, M.; Ortwerth, B. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996, 63, 649–655. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb05669.x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Makama, A. B.; Salmiaton, A.; Choong, T. S. Y.; Hamid, M. R. A.; Abdullah, N.; Saion, E. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126689. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126689

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, R.; Gao, R.; Huang, N.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Kong, X. Y.; Ye, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319216. doi:10.1002/anie.202319216

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, L.; Zhang, M.; Shi, S.; Lv, J.; Song, X.; He, G.; Sun, Z. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 621. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-9-621

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, M.; Lu, B.; Ke, Q.-F.; Guo, Y.-J.; Guo, Y.-P. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 333, 88–98. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.03.019

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 34. | Yang, L.; Zhang, M.; Shi, S.; Lv, J.; Song, X.; He, G.; Sun, Z. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 621. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-9-621 |

| 13. | Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, G. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 1061–1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.04.058 |

| 13. | Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, G. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 1061–1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.04.058 |

| 35. | Li, M.; Lu, B.; Ke, Q.-F.; Guo, Y.-J.; Guo, Y.-P. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 333, 88–98. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.03.019 |

| 1. | Malmqvist, E.; Fumagalli, D.; Munthe, C.; Larsson, D. G. J. Public Health Ethics 2023, 16, 152–164. doi:10.1093/phe/phad012 |

| 2. | Larsson, D. G. J. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B 2014, 369, 20130571. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0571 |

| 8. | Guo, Q.; Zhou, C.; Ma, Z.; Yang, X. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2019, 31, 1901997. doi:10.1002/adma.201901997 |

| 19. | Zhao, Q.-E.; Wen, W.; Xia, Y.; Wu, J.-M. Thin Solid Films 2018, 648, 103–107. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2018.01.004 |

| 20. | Zhao, Q.-E.; Wen, W.; Xia, Y.; Wu, J.-M. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 124, 192–198. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.09.016 |

| 6. | Rosario-Ortiz, F. L.; Wert, E. C.; Snyder, S. A. Water Res. 2010, 44, 1440–1448. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2009.10.031 |

| 7. | Luo, C.; Ma, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Wu, D. Water Res. 2015, 80, 99–108. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2015.05.019 |

| 21. | Sekiya, T.; Ohta, S.; Kamei, S.; Hanakawa, M.; Kurita, S. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2001, 62, 717–721. doi:10.1016/s0022-3697(00)00229-8 |

| 22. | Cao, S.; Chan, T.-S.; Lu, Y.-R.; Shi, X.; Fu, B.; Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, K.; Alzuabi, S.; Cheng, P.; Liu, M.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Piao, L. Nano Energy 2020, 67, 104287. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104287 |

| 23. | Challagulla, S.; Tarafder, K.; Ganesan, R.; Roy, S. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8783. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08599-2 |

| 4. | Deng, Y.; Debognies, A.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 244, 106084. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2022.106084 |

| 5. | Liu, N.; Jin, X.; Feng, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, F.; Johnson, A. C.; Xiao, H.; Hollert, H.; Giesy, J. P. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105454. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2019.105454 |

| 17. | Gu, Y.-J.; Wen, W.; Wu, J.-M. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 21078–21086. doi:10.1039/c8ta07561a |

| 3. | Enna, S. J.; Bylund, D. B., Eds. xPharm: the comprehensive pharmacology reference; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2008. |

| 18. | Wu, J.-M.; Xue, H.-X. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 2139–2143. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03153.x |

| 13. | Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, G. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 1061–1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.04.058 |

| 16. | Wu, J.-M.; Zhao, Q.-E. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 527, 146779. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146779 |

| 12. | Cao, X.; Tian, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, W.; Tian, C.; Fu, H. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 4366–4374. doi:10.1039/c3ta14272h |

| 16. | Wu, J.-M.; Zhao, Q.-E. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 527, 146779. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146779 |

| 11. | Yue, Y.; Yue, X.; Tang, X.; Han, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Du, C. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30817. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30817 |

| 9. | Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2557–2567. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.12.086 |

| 10. | Reghunath, S.; Pinheiro, D.; KR, S. D. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 3, 100063. doi:10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100063 |

| 14. | Lin, Y. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 1246–1248. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2007.08.021 |

| 15. | Lv, X.; Zhang, H.; Chang, H. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 789–795. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.07.059 |

| 17. | Gu, Y.-J.; Wen, W.; Wu, J.-M. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 21078–21086. doi:10.1039/c8ta07561a |

| 17. | Gu, Y.-J.; Wen, W.; Wu, J.-M. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 21078–21086. doi:10.1039/c8ta07561a |

| 24. | Madhusudan Reddy, K.; Manorama, S. V.; Ramachandra Reddy, A. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003, 78, 239–245. doi:10.1016/s0254-0584(02)00343-7 |

| 32. | Makama, A. B.; Salmiaton, A.; Choong, T. S. Y.; Hamid, M. R. A.; Abdullah, N.; Saion, E. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126689. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126689 |

| 33. | Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, R.; Gao, R.; Huang, N.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Kong, X. Y.; Ye, L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319216. doi:10.1002/anie.202319216 |

| 30. | Harun, N.; Sheng, C. K.; Sabri, M. G. M.; Dagang, A. N.; Salleh, H. J. Optoelectron. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 12, 9–15. doi:10.15251/jobm.2020.121.9 |

| 31. | Linetsky, M.; Ortwerth, B. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996, 63, 649–655. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb05669.x |

| 28. | Saha, D.; Desipio, M. M.; Hoinkis, T. J.; Smeltz, E. J.; Thorpe, R.; Hensley, D. K.; Fischer-Drowos, S. G.; Chen, J. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4927–4936. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2018.07.030 |

| 29. | Barakat, M. A.; Tseng, J. M.; Huang, C. P. Appl. Catal., B 2005, 59, 99–104. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.01.004 |

| 25. | Du, X.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; Han, B.; Su, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Li, M.; Tang, H.; Li, G.; Qiao, B. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5811. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19484-4 |

| 26. | Xing, H.; Wen, W.; Wu, J.-M. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2019, 382, 111958. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.111958 |

| 27. | Wang, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, H. Appl. Catal., B 2013, 134–135, 198–204. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.01.006 |

© 2025 Hussain et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjnano/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.