Abstract

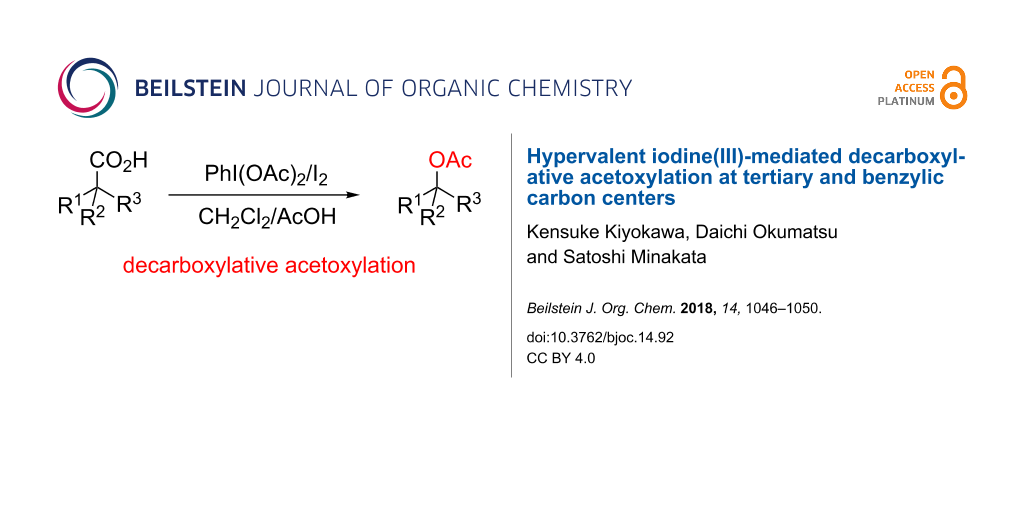

The decarboxylative acetoxylation of carboxylic acids using a combination of PhI(OAc)2 and I2 in a CH2Cl2/AcOH mixed solvent is reported. The reaction was successfully applied to two types of carboxylic acids containing an α-quaternary and a benzylic carbon center under mild reaction conditions. The resulting acetates were readily converted into the corresponding alcohols by hydrolysis.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The decarboxylative functionalization of carboxylic acids and the derivatives thereof is an important transformation in organic synthesis. In recent years, increasing efforts have been devoted to the development of decarboxylative transformations [1-13], especially through radical decarboxylation processes, allowing an easy access to valuable compounds from readily available carboxylic acids. However, despite these advances, the oxidative decarboxylation coupled with C–O bond formation has received considerably less attention, even though it represents a promising strategy for the synthesis of valuable alcohol derivatives. One of the classical methods for the decarboxylative C–O bond formation of aliphatic carboxylic acids involves the use of stoichiometric amounts of heavy metal oxidants under high-temperature conditions [14,15]. Because these oxidants are typically highly toxic, their use has remained limited in organic synthesis. Barton et al. reported on the development of a practical method for the decarboxylative hydroxylation using thiohydroxamate esters as substrates [16]. Although the method was applicable to a broader range of substrates, the preparation of the activated ester is an intrinsic drawback to this procedure. While more convenient and practical methods for decarboxylative oxygenation, in which carboxylic acids are directly used as a substrate, have recently emerged, these methods have limited substrate scope [17-20].

A seminal work on decarboxylative functionalization in which a combination of PhI(OAc)2 and molecular iodine (I2) are used was reported by Suárez et al. [21]. The method features mild reaction conditions, simple operation, and the use of readily available and environmentally friendly oxidants. However, despite the great potential of this approach with respect to a decarboxylative C–O bond-forming reaction, the oxidation system was only applied to reactions of uronic acids and α-amino acids [22-24], and further applications have not been explored. We recently reported on the decarboxylative Ritter-type amination of carboxylic acids containing an α-quaternary carbon center using a combination of PhI(OAc)2 and I2 to produce the corresponding α-tertiary amine derivatives (Scheme 1) [25]. Mechanistic investigations indicated that the reaction proceeds via the formation of an alkyl iodide and the corresponding iodine(III) species as key intermediates. In this context, we concluded that the use of such an oxidation system, combined with the judicious choice of solvent, would enable a decarboxylative C–O bond forming reaction, namely acetoxylation, via the oxidative displacement of an iodine atom of the in situ generated alkyl iodide by PhI(OAc)2 [26]. Herein, we report on the decarboxylative acetoxylation of carboxylic acids that contain an α-quaternary carbon center using PhI(OAc)2 and I2 in a CH2Cl2/AcOH mixed solvent (Scheme 1). In subsequent experiments, the method was also found to be applicable to the reaction of benzylic carboxylic acids. The acetates that were produced in the reaction were readily converted into the corresponding alcohols by hydrolysis.

Scheme 1: Decarboxylative functionalization using PhI(OAc)2/I2 system.

Scheme 1: Decarboxylative functionalization using PhI(OAc)2/I2 system.

Results and Discussion

We started our investigation by examining the decarboxylative acetoxylation of 3-(4-bromophenyl)-2,2-dimethylpropanoic acid (1a) using PhI(OAc)2 and I2 as oxidants. When the reaction was conducted in AcOH, the corresponding acetate 2a was obtained in low yield, and substantial amounts of the starting material were recovered, even though the use of AcOH as the solvent would be expected to promote the acetoxylation (Table 1, entry 1). Other solvents were then screened in attempts to improve the yield of the acetate 2a. Halogenated solvents such as CH2Cl2, 1,2-dichloroethane, and chlorobenzene were found to be more effective in producing 2a in moderate yields (Table 1, entries 2–4). The use of nitromethane also resulted in an improved yield of 2a of 60% (Table 1, entry 5). Interestingly, screening of additional solvents revealed that a CH2Cl2/AcOH mixed solvent was suitable for this transformation, and a ratio of 1:1 (v/v) was found to be optimal, with 2a being produced in 73% yield (Table 1, entries 6–8). When the reaction was performed at a higher concentration, the yield of product remained the same (Table 1, entry 9). Increasing the amount of oxidants used had only a slight effect on the product yield, with 2a being produced in 77% yield, when 3 equiv of PhI(OAc)2 were used (Table 1, entries 10 and 11). The reaction efficiency was significantly decreased with a catalytic amount of I2, and no reaction was observed in the absence of I2 (Table 1, entries 12 and 13). The reaction did not proceed in the dark, and most of the starting material was recovered (Table 1, entry 14). This result is consistent with a reaction proceeding via a light-induced radical decarboxylation process [21,25].

Table 1: Effect of solvents and reaction parameters on the decarboxylative acetoxylation.a

|

|

||

| Entry | Solvent | Yield (%)b |

| 1 | AcOH | 10 |

| 2 | CH2Cl2 | 48 |

| 3 | 1,2-dichloroethane | 46 |

| 4 | chlorobenzene | 42 |

| 5 | CH3NO2 | 60 |

| 6 | CH2Cl2/AcOH (1:1) | 73 |

| 7 | CH2Cl2/AcOH (3:1) | 57 |

| 8 | CH2Cl2/AcOH (1:3) | 65 |

| 9c | CH2Cl2/AcOH (1:1) | 74 |

| 10d | CH2Cl2/AcOH (1:1) | 77 |

| 11e | CH2Cl2/AcOH (1:1) | 75 |

| 12f | CH2Cl2/AcOH (1:1) | 8 |

| 13g | CH2Cl2/AcOH (1:1) | 0 |

| 14h | CH2Cl2/AcOH (1:1) | <5 |

aReactions were conducted on a 0.2 mmol scale at a 0.2 M concentration. Unless otherwise noted, reactions were performed on the benchtop with a fluorescent light on the ceiling. bDetermined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude product using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an internal standard. cThe reaction was conducted at a 0.4 M concentration. dPhI(OAc)2 (3 equiv) was used. eI2 (1 equiv) was used. fI2 (0.1 equiv) was used. gThe reaction was conducted without I2. hThe reaction was conducted in the dark.

We next explored the scope of the decarboxylative acetoxylation reaction (Scheme 2). A variety of carboxylic acids containing α-quaternary carbon centers were efficiently converted into the corresponding acetates under mild reaction conditions [27]. Various functional groups, including bromo (2a and 2f), fluoro (2b), carboxyl (2e), nitro (2g), and ester (2h) groups, were all well tolerated, providing the corresponding products in good yields. Notably, a carboxyl group on the phenyl ring was inert toward decarboxylation under the oxidation conditions used, allowing the acetate 2e to be successfully synthesized. The acetoxylation of a cyclohexane framework was also achieved, but the yield of the product 2j was somewhat lower than that of a non-cyclic 2i. Using this protocol, 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid was smoothly transformed into the corresponding acetate 2k. In addition to the reaction with respect to tertiary carbon centers, the present method was successfully applied to benzylic carboxylic acid derivatives. For example, commercially available arylpropanoic acids, which include ibuprofen (1m) and loxoprofen (1n), underwent decarboxylative acetoxylation in a highly efficient manner. It should be noted that, although benzylic C–H bonds are frequently incompatible with oxidative conditions, no products derived from benzylic C–H oxidation were observed in this reaction system.

Scheme 2: Substrate scope. Reactions were conducted on a 0.5 mmol scale at a 0.2 or 0.4 M concentration on the benchtop with a fluorescent light on the ceiling. Yields are for isolated products. aPhI(OAc)2 (3 equiv) was used. bI2 (1 equiv) was used. cI2 (0.75 equiv) was used.

Scheme 2: Substrate scope. Reactions were conducted on a 0.5 mmol scale at a 0.2 or 0.4 M concentration on th...

Hydrolysis of the acetates 2c and 2m under basic conditions furnished the corresponding alcohols 3c and 3m, respectively, in nearly quantitative yields (Scheme 3). These results demonstrate that the present decarboxylative acetoxylation, followed by hydrolysis, offers an efficient and practical method for the synthesis of tertiary and benzylic alcohols.

The following experiments were performed in attempts to gain insights into the reaction pathway. Monitoring the reaction by 1H NMR spectroscopy showed for the reaction of a mixture of 1a with two equimolar amounts of PhI(OAc)2 in a CD2Cl2/CD3CO2D (1:1) mixed solvent the formation of a mixture of PhI(OAc)2 and 4a in a ratio of 11:1. This result indicates that ligand exchange between 1a and PhI(OAc)2 was suppressed due to the presence of an excess amount of acetic acid (Scheme 4a, see Supporting Information File 1 for details). Based on our previous work, we propose that the reaction pathway involves the formation of an alkyl iodide and the corresponding tertiary alkyl-λ3-iodane species as intermediates [25]. To confirm the participation of these intermediates, the acetoxylation of a separately prepared sample of the tertiary alkyl iodide 5 was investigated. When 5 was treated with one equivalent of PhI(OAc)2 in a CH2Cl2/AcOH mixed solvent at room temperature, the acetoxylation proceeded efficiently to provide 2c (Scheme 4b). On the contrary, in the absence of PhI(OAc)2, no products were formed, and the starting material was recovered. These results strongly support a reaction pathway involving the formation of an alkyl iodide, which is oxidized by PhI(OAc)2 to the corresponding hypervalent iodine(III) species that then undergoes acetoxylation.

Based on the experimental results and our previous report [25], a proposed reaction pathway is depicted in Scheme 5. At the beginning of the reaction, PhI(OAc)2 predominantly exists rather than 4, as confirmed by NMR analysis. Therefore, in the initial stage, PhI(OAc)2 preferentially undergoes decomposition with I2 to provide acetyl hypoiodite (AcOI), which participates in the generation of RCO2I by reacting with a carboxylic acid 1. Meanwhile, RCO2I is directly generated along with AcOI when 4 reacts with I2. Subsequently, decarboxylative iodination of RCO2I under irradiation with visible light affords an alkyl iodide intermediate, which is then rapidly oxidized by the remaining PhI(OAc)2 to generate the corresponding alkyl-λ3-iodane (RI(OAc)2), which then undergoes the acetoxylation to afford the acetate 2 along with the regeneration of AcOI [28].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the decarboxylative acetoxylation of carboxylic acids containing α-quaternary and benzylic carbon centers was achieved by using a combination of PhI(OAc)2 and I2 in a CH2Cl2/AcOH mixed solvent. The key to the success of the reaction was the choice of a suitable solvent that enables an oxidative substitution of an alkyl iodide intermediate by PhI(OAc)2. This operationally simple method under metal-free and mild reaction conditions can be used to produce a variety of acetates, which can be efficiently transformed into tertiary and benzylic alcohols.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental procedures, characterization data, copies of the 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.3 MB | Download |

References

-

Twilton, J.; Le, C.; Zhang, P.; Shaw, M. H.; Evans, R. W.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, No. 0052. doi:10.1038/s41570-017-0052

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wei, Y.; Hu, P.; Zhang, M.; Su, W. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8864–8907. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00516

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, Y.; Ge, L.; Muhammad, M. T.; Bao, H. Synthesis 2017, 49, 5263–5284. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1590935

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yin, F.; Su, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4258–4263. doi:10.1021/ja210361z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yin, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 10401–10404. doi:10.1021/ja3048255

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Cui, L.; Li, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9820–9823. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b06821

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Candish, L.; Teders, M.; Glorius, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7440–7443. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b03127

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Perry, G. J. P.; Quibell, J. M.; Panigrahi, A.; Larrosa, I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11527–11536. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b05155

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, W.; Wurz, R. P.; Peters, J. C.; Fu, G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12153–12156. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b07546

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, D.; Zhu, N.; Chen, P.; Lin, Z.; Liu, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15632–15635. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b09802

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Li, C.; Wang, J.; Barton, L. M.; Yu, S.; Tian, M.; Peter, D. S.; Kumar, M.; Yu, A. W.; Johnson, K. A.; Chatterjee, A. K.; Yan, M.; Baran, P. S. Science 2017, 356, eaam7355. doi:10.1126/science.aam7355

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fawcett, A.; Pradeilles, J.; Wang, Y.; Mutsuga, T.; Myers, E. L.; Aggarwal, V. K. Science 2017, 357, 283–286. doi:10.1126/science.aan3679

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xue, W.; Oestreich, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11649–11652. doi:10.1002/anie.201706611

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Mosher, W. A.; Kehr, C. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 3172–3176. doi:10.1021/ja01109a039

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bacha, J. D.; Kochi, J. K. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 83–93. doi:10.1021/jo01265a016

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Barton, D. H. R.; Géro, S. D.; Holliday, P.; Quiclet-Sire, B.; Zard, S. Z. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 6751–6756. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00337-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kiyokawa, K.; Yahata, S.; Kojima, T.; Minakata, S. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4646–4649. doi:10.1021/ol5022433

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yu, L.; Tan, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4476–4478. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02142

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Song, H.-T.; Ding, W.; Zhou, Q.-Q.; Liu, J.; Lu, L.-Q.; Xiao, W.-J. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7250–7255. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01360

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yuan, Z.; Zhao, T.; Yu, T.; Wang, J.; Wei, H. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2017, 6, 262–264. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201600607

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Concepción, J. I.; Francisco, C. G.; Freire, R.; Hernández, R.; Salazar, J. A.; Suárez, E. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 402–404. doi:10.1021/jo00353a026

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Francisco, C. G.; González, C. C.; Suárez, E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 4141–4144. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00805-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boto, A.; Hernández, R.; Suárez, E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 5945–5948. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(99)01180-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boto, A.; Hernández, R.; Suárez, E. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4930–4937. doi:10.1021/jo000356t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kiyokawa, K.; Watanabe, T.; Fra, L.; Kojima, T.; Minakata, S. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 11711–11720. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b01202

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Gallos, J.; Varvoglis, A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1983, 1999–2002. doi:10.1039/p19830001999

Return to citation in text: [1] -

No product was observed when dodecanoic acid was used as a substrate.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

The substitution by an acetate likely proceeds via a cationic intermediate. However, the detail of the mechanism as well as the stereochemical course of the step is not clear at this stage.

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Twilton, J.; Le, C.; Zhang, P.; Shaw, M. H.; Evans, R. W.; MacMillan, D. W. C. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, No. 0052. doi:10.1038/s41570-017-0052 |

| 2. | Wei, Y.; Hu, P.; Zhang, M.; Su, W. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8864–8907. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00516 |

| 3. | Li, Y.; Ge, L.; Muhammad, M. T.; Bao, H. Synthesis 2017, 49, 5263–5284. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1590935 |

| 4. | Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yin, F.; Su, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4258–4263. doi:10.1021/ja210361z |

| 5. | Yin, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 10401–10404. doi:10.1021/ja3048255 |

| 6. | Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Cui, L.; Li, C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9820–9823. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b06821 |

| 7. | Candish, L.; Teders, M.; Glorius, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7440–7443. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b03127 |

| 8. | Perry, G. J. P.; Quibell, J. M.; Panigrahi, A.; Larrosa, I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11527–11536. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b05155 |

| 9. | Zhao, W.; Wurz, R. P.; Peters, J. C.; Fu, G. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12153–12156. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b07546 |

| 10. | Wang, D.; Zhu, N.; Chen, P.; Lin, Z.; Liu, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15632–15635. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b09802 |

| 11. | Li, C.; Wang, J.; Barton, L. M.; Yu, S.; Tian, M.; Peter, D. S.; Kumar, M.; Yu, A. W.; Johnson, K. A.; Chatterjee, A. K.; Yan, M.; Baran, P. S. Science 2017, 356, eaam7355. doi:10.1126/science.aam7355 |

| 12. | Fawcett, A.; Pradeilles, J.; Wang, Y.; Mutsuga, T.; Myers, E. L.; Aggarwal, V. K. Science 2017, 357, 283–286. doi:10.1126/science.aan3679 |

| 13. | Xue, W.; Oestreich, M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11649–11652. doi:10.1002/anie.201706611 |

| 21. | Concepción, J. I.; Francisco, C. G.; Freire, R.; Hernández, R.; Salazar, J. A.; Suárez, E. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 402–404. doi:10.1021/jo00353a026 |

| 17. | Kiyokawa, K.; Yahata, S.; Kojima, T.; Minakata, S. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4646–4649. doi:10.1021/ol5022433 |

| 18. | Xu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yu, L.; Tan, J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4476–4478. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02142 |

| 19. | Song, H.-T.; Ding, W.; Zhou, Q.-Q.; Liu, J.; Lu, L.-Q.; Xiao, W.-J. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7250–7255. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01360 |

| 20. | Yuan, Z.; Zhao, T.; Yu, T.; Wang, J.; Wei, H. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2017, 6, 262–264. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201600607 |

| 16. | Barton, D. H. R.; Géro, S. D.; Holliday, P.; Quiclet-Sire, B.; Zard, S. Z. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 6751–6756. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00337-8 |

| 28. | The substitution by an acetate likely proceeds via a cationic intermediate. However, the detail of the mechanism as well as the stereochemical course of the step is not clear at this stage. |

| 14. | Mosher, W. A.; Kehr, C. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 3172–3176. doi:10.1021/ja01109a039 |

| 15. | Bacha, J. D.; Kochi, J. K. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 83–93. doi:10.1021/jo01265a016 |

| 21. | Concepción, J. I.; Francisco, C. G.; Freire, R.; Hernández, R.; Salazar, J. A.; Suárez, E. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 402–404. doi:10.1021/jo00353a026 |

| 25. | Kiyokawa, K.; Watanabe, T.; Fra, L.; Kojima, T.; Minakata, S. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 11711–11720. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b01202 |

| 25. | Kiyokawa, K.; Watanabe, T.; Fra, L.; Kojima, T.; Minakata, S. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 11711–11720. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b01202 |

| 26. | Gallos, J.; Varvoglis, A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1983, 1999–2002. doi:10.1039/p19830001999 |

| 25. | Kiyokawa, K.; Watanabe, T.; Fra, L.; Kojima, T.; Minakata, S. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 11711–11720. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b01202 |

| 25. | Kiyokawa, K.; Watanabe, T.; Fra, L.; Kojima, T.; Minakata, S. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 11711–11720. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.7b01202 |

| 22. | Francisco, C. G.; González, C. C.; Suárez, E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 4141–4144. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00805-8 |

| 23. | Boto, A.; Hernández, R.; Suárez, E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 5945–5948. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(99)01180-6 |

| 24. | Boto, A.; Hernández, R.; Suárez, E. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4930–4937. doi:10.1021/jo000356t |

© 2018 Kiyokawa et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)