Abstract

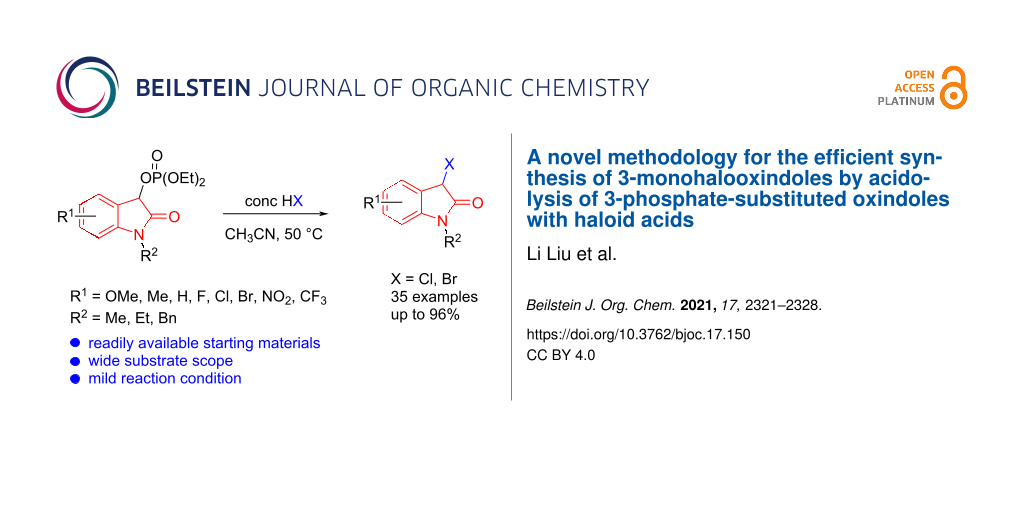

A novel method for the synthesis of 3-monohalooxindoles by acidolysis of isatin-derived 3-phosphate-substituted oxindoles with haloid acids was developed. This synthetic strategy involved the preparation of 3-phosphate-substituted oxindole intermediates and SN1 reactions with haloid acids. This new procedure features mild reaction conditions, simple operation, good yield, readily available and inexpensive starting materials, and gram-scalability.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

3-Monohalooxindole heterocycles are not only present as a characteristic structural motif in numerous biological and medicinal molecules [1,2] but also possess dual nucleophilic and electrophilic character at the C-3 position. Owing to the dual nature at the C-3 position, 3-monohalooxindoles have emerged as a class of versatile building blocks for the construction of various 3,3-disubstituted oxindole and spirooxindole derivatives, such as spirocyclopropaneoxindoles [3-11], 3-β-amino-substituted 3-halooxindoles [12-14], five-membered-ring-based spirooxindoles [15-18] and 3-alkyl-substituted 3-fluorooxindoles (Figure 1) [19]. Despite the importance of 3-monohalooxindoles in organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry, only a few methods for the synthesis of these 3-monohalooxindoles have been reported. Recently, Xu and co-workers disclosed the application of N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide (NFSI) and NBS (N-bromosuccinimide), respectively, as the halogen sources, with diazoacetamide under catalyst-free conditions via a carbene pathway, which constructed 3-fluorooxindoles and 3-bromooxindoles (Scheme 1, reaction 1) [20,21]. Then, the Prathima group established an expedient approach for the direct oxidative chlorination of indole-3-carboxaldehyde to 3-monochlorooxindoles using a combination of NaCl and oxone as the chlorine source and oxidant in a CH3CN/H2O 1:1 system (Scheme 1, reaction 2) [22].

Figure 1: Representation of bioactive molecules and applications.

Figure 1: Representation of bioactive molecules and applications.

Scheme 1: Synthetic methodologies for 3-monohalooxindoles.

Scheme 1: Synthetic methodologies for 3-monohalooxindoles.

Nearly at the same time, Yu and co-workers reported controllable mono- and dichlorooxidation of indoles with hypervalent iodine species in DMF/CF3CO2H/H2O at room temperature, which generated 3,3-dichlorooxindoles and 3-monochlorooxindoles, respectively (Scheme 1, reaction 3) [23]. Apart from these methods, most traditional approaches to 3-monohalooxindoles involve the direct halogenation of oxindoles with various reactive halogenating reagents, including N-chloro-N-methoxybenzenesulfonamide [24,25], ammonium halides/oxone [13], Selectfluor® [26,27], and CuBr2 (Scheme 1, reaction 4) [15]. However, these protocols each have a certain scope and limitations. The development of methods that provide efficient access to a wide range of 3-monohalooxindoles from readily available and inexpensive starting materials is still a formidable challenge because the synthesis should be practical for large-scale industrial use and feature reasonably priced products. Thus, further work is needed to develop a novel strategy for an efficient synthesis of such a versatile synthon.

On the other hand, diethyl (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphates 2 were easily prepared by the base-catalyzed phospha-Brook rearrangement of isatins 1 with diethyl phosphite [28,29]. This compound has a remarkable structural feature: the phosphate moiety is located at the benzylic position as well as at the position α to an amide group, which makes it a good leaving group for the design and development of new reactions. Accordingly, diethyl (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphates 2 have been used recently as precursors in Friedel–Crafts reactions of arenes [30,31] and cross-coupling reactions of arylboronic reagents [32]. However, the direct SN1 reaction of such isatin-derived 3-phosphate-substituted oxindoles by halide ions as nucleophiles has not been developed yet and remains an unsolved challenge in chemistry.

In order to achieve this goal, and on the basis of our previous experiences in the functionalization of oxindoles [33,34], we herein designed a nucleophilic substitution method of an isatin-derived 3-phosphate-substituted oxindole with haloid acids, leading to 3-monohalooxindoles (Scheme 1).

Results and Discussion

During the exploratory study of this work, we chose concentrated hydrochloric acid (36%) as the readily available chlorinating reagent to screen the reaction conditions, and we carried out our initial synthetic reaction with diethyl (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphate (2a) under solvent-free and catalyst-free conditions at room temperature (Table 1, entry 1). To our delight, the desired product 3a was obtained in 19% yield. To further improve the yield, we firstly probed the solvent effect using methanol, THF, toluene, ClCH2CH2Cl, 1,4-dioxane, chloroform, dichloromethane, and acetonitrile (Table 1, entries 2–9). The results indicated that the solvent has a meaningful impact on the efficiency of the reaction. Among the tested solvents, CH3CN was the best choice for the process (Table 1, entry 9). In this instance, a high yield (89%) was achieved. Then, in the presence of the best solvent CH3CN, we tested the effect of the temperature on the reaction. Lowering the reaction temperature to 0 °C and 10 °C, respectively, led to a failure of the reaction (Table 1, entries 10 and 11), while elevating the reaction temperature from 40 °C to 50 °C resulted in the highest yield (92%, Table 1, entry 13). However, further increasing the reaction temperature to 60 °C led to a sharp decrease of the yield (Table 1, entry 14). Therefore, 50 °C was set as the most suitable reaction temperature. Furthermore, we evaluated the effect of the reaction time on the acidolysis reaction (Table 1, entry 15). Prolonging the reaction time to 8 h did not improve the yield (Table 1, entry 15), whereas shortening the reaction time to 5 h reduced the yield (Table 1, entry 16), and thus revealing 6 h to be best reaction time. Finally, the effect of Lewis acid catalysts, such as ZnCl2, FeCl3, AlCl3, Cu (CF3SO3)2, and CuCl2, on the reaction was also examined, but no significant improvement in the yield was found (Table 1, entries 17–21). Considering all of the reaction parameters, the optimal reaction conditions were chosen as shown in Table 1, entry 13.

Table 1: Optimization studies.a

|

|

|||||

| entry | catalyst | solvent | T (°C) | t (h) | yieldc (%) |

| 1 | — | — | rt | 6 | 19 |

| 2 | — | CH3OH | rt | 6 | 49 |

| 3 | — | THF | rt | 6 | trace |

| 4 | — | toluene | rt | 6 | 68 |

| 5 | — | ClCH2CH2Cl | rt | 6 | 68 |

| 6 | — | 1,4-dioxane | rt | 6 | 28 |

| 7 | — | CHCl3 | rt | 6 | 82 |

| 8 | — | CH2Cl2 | rt | 6 | 67 |

| 9 | — | CH3CN | rt | 6 | 89 |

| 10 | — | CH3CN | 0 | 6 | trace |

| 11 | — | CH3CN | 10 | 6 | 38 |

| 12 | — | CH3CN | 40 | 6 | 88 |

| 13 | — | CH3CN | 50 | 6 | 92 |

| 14 | — | CH3CN | 60 | 6 | 86 |

| 15 | — | CH3CN | 50 | 8 | 92 |

| 16 | — | CH3CN | 50 | 5 | 85 |

| 17 | ZnCl2 | CH3CN | 50 | 6 | 91 |

| 18 | FeCl3 | CH3CN | 50 | 6 | 90 |

| 19 | AlCl3 | CH3CN | 50 | 6 | 90 |

| 20 | Cu(CF3SO3)2 | CH3CN | 50 | 6 | 58 |

| 21 | CuCl | CH3CN | 50 | 6 | 87 |

aReaction conditions: 2a (0.2 mmol), solvent (2mL). bConcentrated hydrochloric acid (36%, 15 equiv). cIsolated yield.

Once the optimization studies were concluded, we focused our attention on investigating the substrate scope and generality of this protocol. First, we examined the substrate scope of this transformation between hydrochloric acid (36%) with various substituted (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphates 2. As shown in Scheme 2, this reaction was applicable to a wide range of substrates, which generally offered the corresponding 3-monochlorooxindoles 3a–r with a good yield (51–96%), regardless of the electronic nature and position of the substituents on the aromatic ring of 2. In detail, (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphates with an electron-donating methyl or methoxy substituent gave a better yield (see 3b and 3c) than starting materials with an electron-withdrawing group, such as a NO2, CF3, Cl, Br, or F substituent (see 3d–g, 3j, 3k, and 3o). Surprisingly, a phosphate possessing two electron-withdrawing substituents in the form of a 4,6-difluoro motif allowed to access the corresponding product 3l in a higher yield. Notably, phosphate 2a with no substitution on the aromatic ring and on the nitrogen atom showed a good reactivity, furnishing the corresponding product 3a in the highest yield, possibly owing to not having steric hindrance. It appeared that the position of the residue R1 on the aryl ring exerted a pronounced effect on the reactivity. For instance, 4-bromo-, 4-chloro-, 4,6-difluoro-, 7-fluoro-, and 7-chloro-substituted phosphates afforded the corresponding products 3h, 3i, and 3l–n in a higher yield than the 5-fluoro-, 5-bromo-, 6-fluoro-, and 6-bromo-substituted phosphates (see 3d, 3f, 3j, and 3k). In addition, N-protected (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphates with R2 = Me, Et, and Bn, respectively, were also found to be suitable for the transformation and gave the respective products 3p–r in good yield (73–88%, Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Substrate scope of the acidolysis of isatin-derived phosphates 2 with hydrochloric acid. Standard reaction conditions: 2a–r (0.5 mmol), respectively, hydrochloric acid (7.5 mmol, 15 equiv), CH3CN (3 mL), 50 °C, 6 h. The isolated yields are given.

Scheme 2: Substrate scope of the acidolysis of isatin-derived phosphates 2 with hydrochloric acid. Standard r...

In order to further extend the substrate scope, we tried using hydrobromic acid (40%) as a bromine source in the reaction, and the results are summarized in Scheme 3. Generally, the phosphate substrates 2 substituted with electron-donating substituents were more reactive than those with electron-withdrawing motifs, and thus gave a better result. For example, the (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphate substrates with a methyl or methoxy group at the 5-position of the benzene ring could all react with hydrobromic acid in good yield, giving 4b, 4c, and 4g in 72–76% yield. The position of the residue R1 on the phenyl ring of the (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphate had an obvious effect on the reactivity. For example, (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphates bearing a bromo or fluoro substituent in the 6-position all gave the corresponding products in a higher yield than the analogous precursors substituted in the 5-position (see 4i and 4j vs 4d and 4f). Moreover, there was seemingly no significant difference in the reactivity of the starting materials carrying a chloro substituent in the 4- and the 7-position, respectively, since the products 4h and 4l were obtained in a comparable yield of 66 and 58%, respectively. The substrate with no residue R1 on the phenyl ring produced the corresponding product 4a in a higher yield than some the substituted substrates. In addition, N-protected (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphate substrates could also deliver the products in good yield (see 4m–o), even though bulkier N-protecting groups, i.e., benzyl and ethyl, slightly decreased the yields of the products (see 4n and 4o).

Scheme 3: Substrate scope of the acidolysis of isatin-derived phosphates 2 with hydrobromic acid. Standard reaction conditions: 2a–2o (0.5 mmol), hydrobromic acid (7.5 mmol, 15 equiv), CH3CN (3 mL), 50 °C, 6 h. The isolated yield is given.

Scheme 3: Substrate scope of the acidolysis of isatin-derived phosphates 2 with hydrobromic acid. Standard re...

Regrettably, when a substrate 2 bearing a strong electron-withdrawing nitro or trifluoromethyl group on the phenyl ring was employed, the reaction gave very complex side products under the standard conditions, and almost no product was observed. In addition, we also tested hydroiodic and hydrofluoric acid as a halogenating reagent in the reaction, which did not provide any desired product. Interestingly, the (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphate substrates could be directly reduced into oxindoles using hydroiodic acid (57%, Scheme 4).

Scheme 4: Reduction of the substrates 2 to the corresponding oxindoles 5.

Scheme 4: Reduction of the substrates 2 to the corresponding oxindoles 5.

To show the utility of this novel method, we performed the syntheses of 3a from Scheme 2 on a 1 mol-scale. This larger-scale reaction smoothly took place to give the product 3a in 95% yield under the standard conditions, which was similar to the result of the smaller-scale reaction, and column chromatography separation is not usually required. This outcome indicated that the transformation could be applicable for larger-scale syntheses of 3-monohalooxindoles products. In addition, the structure of all products 3 and 4 was unambiguously assigned by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy and HRMS. Especially the proton at the C-3-position of 3-monohalooxindoles gave diagnostic singlets (5.25–5.93 Hz) instead of double peaks due to the absence of coupling with the phosphorus atom in the 1H NMR experiment. This indicated that the methylene moiety adjacent to the phosphate group had been displaced by a halogen atom, which further implied that the halogenation reaction with haloid acids had occurred.

On the basis of this study and the early related reports [30,35], an SN1 mechanism for this transformation is proposed as illustrated in Scheme 5. Initially, the C–O bond of the C-3 position of a diethyl (2-oxoindolin-3-yl) phosphate 2 is activated by protonation with a haloid acid. Subsequently the phosphate leaving group is eliminated to generate the carbocation intermediate III, which is then followed by rapid combination with a nucleophilic halide ion to form a 3-monohalooxindoles 3 or 4.

Conclusion

In summary, a new method for the synthesis of 3-monohalooxindoles via acidolysis of isatin-derived 3-phosphate-substituted oxindoles with haloid acids was developed. The present methodology involves the formation of an oxindole having a phosphate moiety at the C-3 position via the [1,2]-phospha-Brook rearrangement under Brønsted base catalysis and the subsequent acidolysis with haloid acids. The mild reaction conditions, simple operation, good yield, and readily available and inexpensive starting materials make this protocol a valuable method for the preparation of various 3-halooxindoles on a large-scale industrial application.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental details as well as compound characterization and spectral data of the products. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 4.7 MB | Download |

References

-

Abourriche, A.; Abboud, Y.; Maoufoud, S.; Mohou, H.; Seffaj, T.; Charrouf, M.; Chaib, N.; Bennamara, A.; Bontemps, N.; Francisco, C. Farmaco 2003, 58, 1351–1354. doi:10.1016/s0014-827x(03)00188-5

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hewawasam, P.; Gribkoff, V. K.; Pendri, Y.; Dworetzky, S. I.; Meanwell, N. A.; Martinez, E.; Boissard, C. G.; Post-Munson, D. J.; Trojnacki, J. T.; Yeleswaram, K.; Pajor, L. M.; Knipe, J.; Gao, Q.; Perrone, R.; Starrett, J. E., Jr. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 1023–1026. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00101-4

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yuan, W.-C.; Lei, C.-W.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Wang, Z.-H.; You, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 2534–2544. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c02653

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, L.; He, J. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 5203–5219. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b03164

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhang, J.-R.; Jin, H.-S.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.-M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 4988–4994. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202000830

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wen, J.-B.; Du, D.-M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 1647–1656. doi:10.1039/c9ob02663k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Song, Y.-X.; Du, D.-M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 5375–5380. doi:10.1039/c9ob00998a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, C. Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 1442–1447. doi:10.1039/c9qo00145j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ošeka, M.; Noole, A.; Žari, S.; Öeren, M.; Järving, I.; Lopp, M.; Kanger, T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 3599–3606. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402061

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Noole, A.; Ošeka, M.; Pehk, T.; Öeren, M.; Järving, I.; Elsegood, M. R. J.; Malkov, A. V.; Lopp, M.; Kanger, T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 829–835. doi:10.1002/adsc.201300019

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Noole, A.; Malkov, A. V.; Kanger, T. Synthesis 2013, 45, 2520–2524. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1338505

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.-Y.; Ren, X. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 5099–5108. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b00007

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Paladhi, S.; Park, S. Y.; Yang, J. W.; Song, C. E. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5336–5339. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02628

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Li, J.; Du, T.; Zhang, G.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1330–1332. doi:10.1039/c2cc38475b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Quan, B.-X.; Zhuo, J.-R.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Zhang, M.-L.; Zhou, M.-Q.; Zhang, X.-M.; Yuan, W.-C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 1886–1891. doi:10.1039/c9ob02733e

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wang, C.-S.; Li, T.-Z.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Zhou, J.; Mei, G.-J.; Shi, F. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 3214–3222. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b03004

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, X.-L.; Liu, S.-J.; Gu, Y.-Q.; Mei, G.-J.; Shi, F. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 3341–3346. doi:10.1002/adsc.201700487

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zheng, P.-F.; Ouyang, Q.; Niu, S.-L.; Shuai, L.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, K.; Liu, T.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9390–9399. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b04792

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ji, J.; Chen, L.-Y.; Qiu, Z.-B.; Ren, X.; Li, Y. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8, 1436–1440. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201900378

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dong, K.; Yan, B.; Chang, S.; Chi, Y.; Qiu, L.; Xu, X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6887–6892. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01286

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, X.; Dong, K.; Yan, B.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, L.; Xu, X. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 70221–70225. doi:10.1039/c6ra16868j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lakshmi Reddy, V.; Prathima, P. S.; Rao, V. J.; Bikshapathi, R. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 20152–20155. doi:10.1039/c8nj04855j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiang, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, L.; Yu, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 6920–6924. doi:10.1039/c9ob01173k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pu, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, Z.; Yang, X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5937–5940. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201601226

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lu, Z.; Li, Q.; Tang, M.; Jiang, P.; Zheng, H.; Yang, X. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 14852–14855. doi:10.1039/c5cc05052a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zheng, B.-Q.; Chen, L.-Y.; Zhao, J.-B.; Ji, J.; Qiu, Z.-B.; Ren, X.; Li, Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 8989–8993. doi:10.1039/c8ob01786g

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Balaraman, K.; Wolf, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1390–1395. doi:10.1002/anie.201608752

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hayashi, M.; Nakamura, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2249–2252. doi:10.1002/anie.201007568

Return to citation in text: [1] -

El Kaïm, L.; Gaultier, L.; Grimaud, L.; Dos Santos, A. Synlett 2005, 2335–2336. doi:10.1055/s-2005-872670

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rokade, B. V.; Guiry, P. J. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 6172–6180. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c00370

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Smith, A. G.; Johnson, J. S. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1784–1787. doi:10.1021/ol100410k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Terada, M.; Kondoh, A.; Takei, A. Synlett 2016, 27, 1848–1853. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1561859

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, T.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Wu, M.; Kong, D. Synthesis 2020, 52, 1387–1397. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1691597

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Huang, T.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Kong, D.; Wu, M. Synthesis 2020, 52, 2689–2697. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1707147

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Emer, E.; Sinisi, R.; Capdevila, M. G.; Petruzziello, D.; De Vincentiis, F.; Cozzi, P. G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 647–666. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201001474

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 30. | Rokade, B. V.; Guiry, P. J. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 6172–6180. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c00370 |

| 35. | Emer, E.; Sinisi, R.; Capdevila, M. G.; Petruzziello, D.; De Vincentiis, F.; Cozzi, P. G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 647–666. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201001474 |

| 1. | Abourriche, A.; Abboud, Y.; Maoufoud, S.; Mohou, H.; Seffaj, T.; Charrouf, M.; Chaib, N.; Bennamara, A.; Bontemps, N.; Francisco, C. Farmaco 2003, 58, 1351–1354. doi:10.1016/s0014-827x(03)00188-5 |

| 2. | Hewawasam, P.; Gribkoff, V. K.; Pendri, Y.; Dworetzky, S. I.; Meanwell, N. A.; Martinez, E.; Boissard, C. G.; Post-Munson, D. J.; Trojnacki, J. T.; Yeleswaram, K.; Pajor, L. M.; Knipe, J.; Gao, Q.; Perrone, R.; Starrett, J. E., Jr. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 1023–1026. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00101-4 |

| 19. | Ji, J.; Chen, L.-Y.; Qiu, Z.-B.; Ren, X.; Li, Y. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8, 1436–1440. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201900378 |

| 32. | Terada, M.; Kondoh, A.; Takei, A. Synlett 2016, 27, 1848–1853. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1561859 |

| 15. | Quan, B.-X.; Zhuo, J.-R.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Zhang, M.-L.; Zhou, M.-Q.; Zhang, X.-M.; Yuan, W.-C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 1886–1891. doi:10.1039/c9ob02733e |

| 16. | Wang, C.-S.; Li, T.-Z.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Zhou, J.; Mei, G.-J.; Shi, F. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 3214–3222. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b03004 |

| 17. | Jiang, X.-L.; Liu, S.-J.; Gu, Y.-Q.; Mei, G.-J.; Shi, F. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 3341–3346. doi:10.1002/adsc.201700487 |

| 18. | Zheng, P.-F.; Ouyang, Q.; Niu, S.-L.; Shuai, L.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, K.; Liu, T.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9390–9399. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b04792 |

| 33. | Huang, T.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Wu, M.; Kong, D. Synthesis 2020, 52, 1387–1397. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1691597 |

| 34. | Huang, T.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Kong, D.; Wu, M. Synthesis 2020, 52, 2689–2697. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1707147 |

| 12. | Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.-Y.; Ren, X. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 5099–5108. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b00007 |

| 13. | Paladhi, S.; Park, S. Y.; Yang, J. W.; Song, C. E. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5336–5339. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02628 |

| 14. | Li, J.; Du, T.; Zhang, G.; Peng, Y. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1330–1332. doi:10.1039/c2cc38475b |

| 28. | Hayashi, M.; Nakamura, S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2249–2252. doi:10.1002/anie.201007568 |

| 29. | El Kaïm, L.; Gaultier, L.; Grimaud, L.; Dos Santos, A. Synlett 2005, 2335–2336. doi:10.1055/s-2005-872670 |

| 3. | Yuan, W.-C.; Lei, C.-W.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Wang, Z.-H.; You, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 2534–2544. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c02653 |

| 4. | Chen, L.; He, J. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 5203–5219. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.9b03164 |

| 5. | Zhang, J.-R.; Jin, H.-S.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.-M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 4988–4994. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202000830 |

| 6. | Wen, J.-B.; Du, D.-M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 1647–1656. doi:10.1039/c9ob02663k |

| 7. | Song, Y.-X.; Du, D.-M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 5375–5380. doi:10.1039/c9ob00998a |

| 8. | Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, C. Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 1442–1447. doi:10.1039/c9qo00145j |

| 9. | Ošeka, M.; Noole, A.; Žari, S.; Öeren, M.; Järving, I.; Lopp, M.; Kanger, T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 3599–3606. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201402061 |

| 10. | Noole, A.; Ošeka, M.; Pehk, T.; Öeren, M.; Järving, I.; Elsegood, M. R. J.; Malkov, A. V.; Lopp, M.; Kanger, T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 829–835. doi:10.1002/adsc.201300019 |

| 11. | Noole, A.; Malkov, A. V.; Kanger, T. Synthesis 2013, 45, 2520–2524. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1338505 |

| 30. | Rokade, B. V.; Guiry, P. J. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 6172–6180. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c00370 |

| 31. | Smith, A. G.; Johnson, J. S. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1784–1787. doi:10.1021/ol100410k |

| 24. | Pu, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, Z.; Yang, X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5937–5940. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201601226 |

| 25. | Lu, Z.; Li, Q.; Tang, M.; Jiang, P.; Zheng, H.; Yang, X. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 14852–14855. doi:10.1039/c5cc05052a |

| 26. | Zheng, B.-Q.; Chen, L.-Y.; Zhao, J.-B.; Ji, J.; Qiu, Z.-B.; Ren, X.; Li, Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 8989–8993. doi:10.1039/c8ob01786g |

| 27. | Balaraman, K.; Wolf, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1390–1395. doi:10.1002/anie.201608752 |

| 23. | Jiang, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, L.; Yu, C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 6920–6924. doi:10.1039/c9ob01173k |

| 15. | Quan, B.-X.; Zhuo, J.-R.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Zhang, M.-L.; Zhou, M.-Q.; Zhang, X.-M.; Yuan, W.-C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 1886–1891. doi:10.1039/c9ob02733e |

| 22. | Lakshmi Reddy, V.; Prathima, P. S.; Rao, V. J.; Bikshapathi, R. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 20152–20155. doi:10.1039/c8nj04855j |

| 20. | Dong, K.; Yan, B.; Chang, S.; Chi, Y.; Qiu, L.; Xu, X. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6887–6892. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.6b01286 |

| 21. | Wang, X.; Dong, K.; Yan, B.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, L.; Xu, X. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 70221–70225. doi:10.1039/c6ra16868j |

| 13. | Paladhi, S.; Park, S. Y.; Yang, J. W.; Song, C. E. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5336–5339. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02628 |

© 2021 Liu et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Please note that the reuse, redistribution and reproduction in particular requires that the author(s) and source are credited and that individual graphics may be subject to special legal provisions.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms)