Abstract

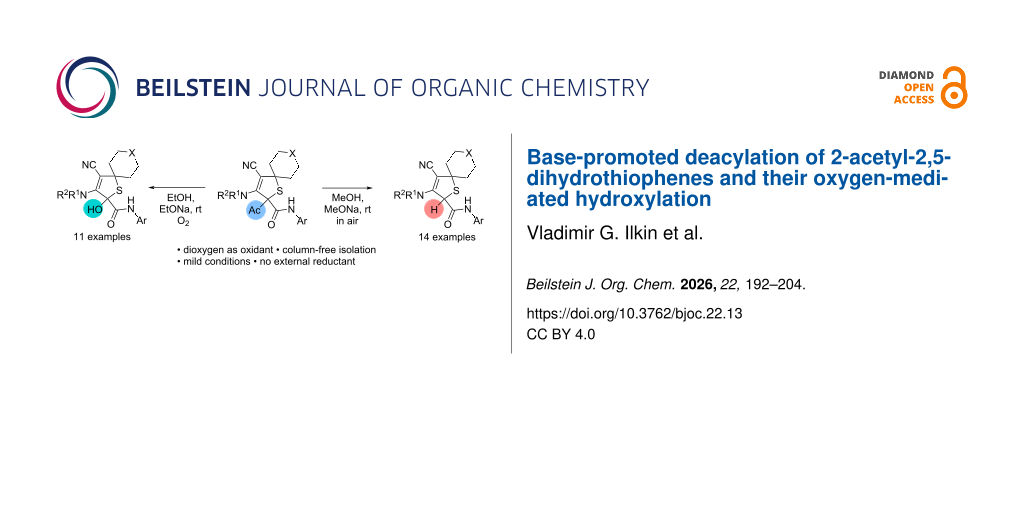

Solvent-dependent transformations of polysubstituted 2-acetyl-2,5-dihydrothiophenes to the corresponding 2-hydroxy- or deacetylated derivatives are described. The treatment of a methanolic solution of the dihydrothiophene substrates with sodium methoxide afforded the deacylated products. Conversely, the treatment with sodium ethoxide in an oxygen saturated ethanolic solution produced 2-hydroxy substituted 2,5-dihydrothiophenes.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Oxidative transformations are an important area of modern organic synthesis [1], producing a broad range of valuable synthetic products for the industry. A variety of catalytic reactions were developed for the oxidative conversions of unsaturated compounds [2-5], alcohols [6,7], alkanes [8-10] and more complex molecules [11]. Rearrangements of the oxidized compounds are equally important transformations [12].

Oxidation of compounds containing a carbonyl group into carboxylic acid derivatives can be divided into two large groups: direct oxidation and oxidative rearrangements. Direct oxidation of ketones includes C‒C-bond cleavage, and carboxylic acids are predominantly formed. This can be achieved by the treatment of acyclic ketones with hypohalites [13], in the nitroarene-catalyzed oxidation with oxygen under basic conditions [14] or by the use of hypervalent iodine compounds (Scheme 1A) [15,16].

Scheme 1: Previous reports (A‒C) and our work (D, E).

Scheme 1: Previous reports (A‒C) and our work (D, E).

Oxidative rearrangements of carbonyl compounds are based on Dakin [17] and Baeyer–Villiger reactions [18] and their modifications.

Cyclic and acyclic ketones were oxidized to afford lactones and esters, accordingly, involving catalytic reactions with hydrogen peroxide [19-22], oxygen [23,24] or with m-CPBA (Scheme 1B) [25,26] or non-catalytic transformations [27].

The few known oxidative transformations of o- or p-hydroxy-substituted aromatic ketones, that in most cases lead to phenols, involve the use of hydrogen peroxide as an oxygen source (Scheme 1C) [20,25,26]. Bernini et al. have developed a catalytic system, containing hydrogen peroxide/methyltrioxorhenium and an ionic liquid, to oxidize acetophenones to afford phenols [20]. Junjappat et al. found that hydrogen peroxide activated by boric acid can act as oxidant for the direct conversion of aromatic ketones to phenols [25]. Hocking has described the oxidation of o-hydroxyacetophenone and some benzophenones with an aqueous alkaline hydrogen peroxide solution [26]. The key steps of oxidation of ketones into phenols include: a) nucleophilic addition of the hydroperoxide anion to the carbonyl carbon; b) [1,2]-aryl migration in the formed tetrahedral intermediate to afford formate ester; c) hydrolysis of the latter to form phenols [28].

The development of methods for the construction of heterocycles and their modification is an important area of organic synthesis [29]. Although the Dakin oxidation has become a convenient tool for the preparation of phenols from aromatic ketones, several specific approaches have been developed for the synthesis of hydroxylated heterocycles [30-34].

The deacylation of ketones is also another important direction of their transformation [35-38]. Dihydrothiophenes can be considered as analogs of organic sulfides. Accordingly, in oxidative reactions they are also easily oxidized to the corresponding sulfoxides [39,40]. Despite the fact that the synthetic applications of dihydrothiophenes are being actively studied [39-46], their oxidative functionalization that does not disrupt the heterocycle or oxidize sulfur has not been previously reported.

Dihydrothiophenes exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activity [47-49]. In this regard, the development of new routes for their modifications with the use of inexpensive and easily available reagents is an important task.

Recently, we have developed a copper(I)/rhodium(II)-catalyzed method toward two types of regioisomeric 2,5-dihydrothiophenes 1 and 4, containing an acetyl group [50]. In this work, to evaluate the synthetic utility of these compounds (the scope is presented at page S3 of Supporting Information File 1) we have studied their transformations in ethanolic or methanolic solutions in the presence of sodium ethoxide or methoxide, accordingly. As a result, catalyst-free oxidation under mild conditions of 2-acetyl-2,5-dihydrothiophenes into 2-hydroxy-substituted products (Scheme 1D) or the deacetylated products (Scheme 1E) have been developed.

Results and Discussion

Dihydrothiophene 1a was selected as a model substrate for our optimization study (Table 1).

Table 1: Optimization of the transformation of dihydrothiophene 1a.a

|

|

|||||

| Entry |

[M] or base

(equiv) |

Solvent

(mL) |

[O] | Acid (mL) |

Yields of 2a/3a,

% |

| 1 | Na (1) | EtOH (2) | O2 | ‒ | 22/36b |

| 2 | Na (2) | EtOH (2) | O2 | ‒ | 21/27b |

| 3 | Na (2) | EtOH (2) | O2 | HCl (0.25) | 30/35b |

| 4 | Na (5) | EtOH (2) | O2 | HCl (0.25) | 41/0 |

| 5 | Na (5) | EtOH (2) | O2 | HCl (0.25) | 51/0c |

| 6 | Na (5) | EtOH (2) | O2 | ‒ | 28/trace |

| 7 | Na (5) | EtOH (2) | O2 | HCl (0.25) | 44/0c,d |

| 8 | Na (5) | MeOH (2) | O2 | HCl (0.25) | trace/71c |

| 9 | Na (5) | MeOH (2) | O2 | HCl (0.25) | 0/78 |

| 10 | Na (5) | iPrOH (2) | O2 | HCl (0.25) | 35/0c |

| 11 | Na (5) | n-BuOH (2) | O2 | HCl (0.25) | 46/0c |

| 12 | Na (5) | TFE | O2 | HCl (0.25) | 0/75 |

| 13 | NaOH (5) | EtOH (2) | 38% H2O2 (0.5) | ‒ | 0/62c |

aConditions: dihydrothiophene 1a (0.12 mmol), dry solvent, [M] or base, rt, 1 h. Water (2 mL) or/and acid were added after evaporation of solvent. Isolated yields after centrifugation in Et2O (2 × 1 mL). bProducts were isolated as a mixture. cOxygen was bubbled (1 min) after Na dissolving. dIce bath. TFE – trifluoroethanol.

Initially, this compound was treated in ethanolic solution (2 mL) at room temperature in air for 1 h in the presence of sodium ethoxide prepared from 1 equiv of sodium. After the reaction had completed, the reaction solution was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was quenched with water and extracted with dichloromethane (DCM). Centrifugation of the concentrated extract in Et2O afforded a mixture of products 2a and 3a in 22 and 36% yields, accordingly (Table 1, entry 1). When the loading of sodium was increased to 2.0 equiv, the yield of deacylated product 3a was slightly decreased to 27% (Table 1, entry 2). 2-Hydroxy-substituted dihydrothiophene 2a was formed additionally in comparable yield (21%, Table 1, entry 2). When acid (HCl) was added after quenching the residue with water, the yields of products 2a and 3a were increased (30 and 35%, Table 1, entry 3).

The selective formation of 2-hydroxy-2,5-dihydrothiophene 2a in 41% yield was achieved when using 5 equiv of sodium and 0.25 mL of HCl (Table 1, entry 4). In the oxygen saturated solution, the product 2a was obtained with increased yield (51%, Table 1, entry 5). When no acid was added, product 2a was isolated in decreased yield (28%, Table 1, entry 6). Conducting the reaction in the oxygen saturated ethanolic solution at 0 °C afforded product 2a in a slightly decreased yield (44%, Table 1, entry 7). To our surprise, when ethanol was replaced with methanol, the deacylated product 3a was isolated as the major product in 71% yield (Table 1, entry 8). In this case, dihydrothiophene 2a formed only in a trace amount. In contact with air this reaction proceeded more selectively, and the pure product 3a was isolated in 78% yield (Table 1, entry 9). Hydroxy-substituted product 2a also formed in solution of iPrOH or n-BuOH, and this product was isolated in 35 or 46% yields, respectively (Table 1, entries 10 and 11). In a solution of TFE the deacylated product 2a was formed in 75% yield (Table 1, entry 12). Carrying out the reaction under Hockings conditions [26] resulted in the selective formation of the deacylated product 3a (Table 1, entry 13).

Thus, the optimized conditions for the synthesis of 2-hydroxy-substituted 2,5-dihydrothiophene 2a were found to be the use of 5.0 equiv of sodium in an oxygen saturated ethanolic solution at rt for 1 h. The deacylated product 3a was synthesized in high yield when the reaction was performed with 5.0 equiv of sodium in methanolic solution at rt for 1 h in contact with air.

With these optimal conditions in hand, we have investigated the oxidation of 2-acetyl-2,5-dihydrothiophenes 1, containing various substituents (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Oxidation of 2-acetyldihydrothiophenes 1. Conditions: dihydrothiophenes 1 (0.12–0.21 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sodium (0.60–1.05 mmol, 5 equiv), and dry EtOH (2.0–3.0 mL). *Scaled-up synthesis: dihydrothiophene 1a (1.17 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sodium (5.87 mmol, 5 equiv), in dry EtOH (5 mL).

Scheme 2: Oxidation of 2-acetyldihydrothiophenes 1. Conditions: dihydrothiophenes 1 (0.12–0.21 mmol, 1.0 equi...

Cyclohexano-, cycloheptano- and cyclooctano-spiroannulated 2-acetyl-3-morpholino-N-phenyl-2,5-dihydrothiophene-2-carboxamides 1a,c,f were oxidized into 2-hydroxy derivatives 2a,c,f in 51–60% yields. Various N-aryl-substituted 2,5-dihydrothiophene-2-carboxamides 1b,d,e,g–j selectively transformed into oxidized products 2b,d,e,g–j in 41–62% yields. Variation of the amine moiety in the cyclooctano-spiroannulated 2-acetyl-N-phenyl-2,5-dihydrothiophene-2-carboxamides showed that the oxidized product formed from morpholine- (1f) and piperidine-substituted (1k) 2,5-dihydrothiophenes in 60 (2f) and 53% (2k) yield. Oxidation of the dimethylamino-substituted 2,5-dihydrothiophene 1l afforded a mixture of products in 25% (OH-substituted, 2l) and 32% (H-substituted, 2l′) yield. Pyrrolidine- and azepane-substituted cyclooctano-spiroannulated 2,5-dihydrothiophenes 1m and 1n were found to be transformed into deacetylated products in 67% (2m) and 60% (2n) yields. When experiments were performed in iPrOH or n-BuOH, we observed the formation of the deacylated product (2n) in 67 and 70% yield, accordingly.

Next, the deacylation of 2-acetyl-2,5-dihydrothiophenes in methanolic solution was investigated (Scheme 3). Cyclohexano-, cycloheptano- and cyclooctano-spiroannulated 2-acetyl-3-morpholino-N-phenyl-2,5-dihydrothiophene-2-carboxamides in these conditions gave deacylated products in 75–78% yield. Different N-aryl substituted 2,5-dihydrothiophene-2-carboxamides selectively formed the deacylated products in 55–74% yield. Variation of the amine moiety in the cyclooctano- and cyclohexano-spiroannulated 2-acetyl-N-phenyl-2,5-dihydrothiophene-2-carboxamides resulted in all cases in the selective formation of the deacylated products in 60–70% yield.

Scheme 3: Deacylation of 2-acetyldihydrothiophenes 1. Conditions: dihydrothiophenes 1 (0.11–0.18 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sodium (0.55–0.88 mmol, 5 equiv), dry MeOH (2.0–3.0 mL).

Scheme 3: Deacylation of 2-acetyldihydrothiophenes 1. Conditions: dihydrothiophenes 1 (0.11–0.18 mmol, 1.0 eq...

In continuation of the research, isomeric dihydrothiophenes (Scheme 1, E) were also treated in ethanolic solution with sodium ethoxide. Initially, cyclohexano-spiroannulated dihydrothiophene 4a was treated with ethanolic solution (3 mL) in the presence of sodium ethoxide obtained from 2 equiv of sodium at rt in air for 1 h. After the reaction was completed, the deacylated product was isolated in 69% yield (Table 2, entry 1). When the loading of sodium was increased up to 5.0 equiv, the yield of deacylated product was slightly increased to 72% (Table 2, entry 2). In a more concentrated ethanol solution (1 mL) the product was obtained in 70% yield (Table 2, entry 3). When the residue was quenched with concentrated HCl (1 mL), the product was isolated in reduced yield (58%, Table 2, entry 4). Adding 0.25 mL of acid (HCl) after quenching the residue with water resulted in an increase in the product yield (74%, Table 2, entry 5). Increasing the amount of sodium up to 10 equiv resulted in a decrease of the yield of the product 5a (61%, Table 2, entry 6).

Table 2: Optimization of the transformation of dihydrothiophene 4a.a

|

|

|||||

| Entry |

Na

(equiv) |

Solvent

(mL) |

Water

(mL) |

HCl

(mL) |

Yield,

(%)b |

| 1 | Na (2) | EtOH (3) | 2 | ‒ | 69 |

| 2 | Na (5) | EtOH (3) | 2 | ‒ | 72 |

| 3 | Na (5) | EtOH (1) | 2 | ‒ | 70 |

| 4 | Na (5) | EtOH (3) | ‒ | 1 | 58 |

| 5 | Na (5) | EtOH (3) | 2 | 0.25 | 74 |

| 6 | Na (10) | EtOH (3) | 2 | 0.25 | 61 |

aConditions: dihydrothiophene 4a (0.19 mmol), rt, 1 h. Water or/and HCl were added after evaporation of the solvent. bIsolated yields after centrifugation in Et2O/hexane (1:2).

Thus, the optimized conditions for the synthesis of dihydrothiophene 5a were found to be the use of 5.0 equiv of sodium in ethanolic solution (3 mL) at rt for 1 h in air (Table 2, entry 5).

With optimal conditions in hand, we have investigated the deacylation of acetyldihydrothiophenes 4a–f, containing various substituents (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4: Synthesis of dihydrothiophenes 5. Conditions: dihydrothiophenes 4 (0.13–0.22 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sodium (0.66–1.11 mmol, 5 equiv), dry EtOH (2.5–3.0 mL).

Scheme 4: Synthesis of dihydrothiophenes 5. Conditions: dihydrothiophenes 4 (0.13–0.22 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sodi...

Thus, cyclohexano-, cyclopentano-, cycloheptano- and cyclooctano-spiroannulated dihydrothiophenes 4a–f were transformed into products 5a–f in 58–90% yield. Piperidine- and azepane-substituted cyclooctano-spiroannulated dihydrothiophenes 4e,f also transformed into deacylated products 5e,f in 71% and 89% yield, respectively.

Several control experiments were performed to find the effect of oxygen, argon, additives and TEMPO on the outcome of the oxidation and deacylation reactions (Scheme 5).

When the deacylated dihydrothiophene 3a, obtained in methanolic solution, was treated with sodium ethoxide in an oxygen-saturated ethanolic solution, 2-hydroxysubstituted product 2a was isolated in 56% yield (Scheme 5, I). On the other hand, isomeric deacylated dihydrothiophene 4a in these conditions did not transform into the oxidized product, and deacylated product 4a was recovered in 88% yield (Scheme 5, II).

Next, the transformation of 1a in an argon saturated ethanolic solution results in the formation of 2-hydroxy-substituted product 2a in low yield (8%), although the yield of the deacylated product 3a increased up to 47% (Scheme 5, III). This suggests the participation of oxygen in the formation of 2-hydroxy-substituted product 2a. When the methanolic solution was saturated with oxygen, the 2-hydroxy-substituted product 2a was not isolated. Only the formation of the deacylated product 3a in 51% yield was observed (Scheme 5, IV).

The influence of a reductant (trimethyl phosphite) on the reaction in methanol was evaluated (Scheme 5, V). This did not have a significant effect on the reaction outcome. Thus, there was no formation of oxidized intermediates during transformation.

The effect of TEMPO (up to 2.0 equiv) was evaluated on the oxidation reaction, and TEMPO was found to not inhibit the formation of 2-hydroxy-substituted product 2a (Scheme 5, VI). Therefore, the reaction is most likely not proceeding via a free radical mechanism.

To clarify the influence of the amide group on the developed transformations, dihydrothiophene 4g bearing a sulfonylimine group instead of an amide was treated with sodium methoxide in methanol or with sodium ethoxide in ethanol (Scheme 5, VII). However, under these conditions only decomposition of 4g was observed, and neither deacetylated nor hydroxylated products were isolated. Interestingly, chromatography of 4g on neutral alumina resulted in elimination of the sulfonylimine group to give compounds 5g. Therefore, the amide group plays an important role in these transformations.

In addition, analysis of the reaction mixture obtained in ethanolic solution was performed after evaporation of the ethanol. HRMS analysis showed the presence of two peaks with m/z values 400.1704 (retention time 7.952‒7.963) and 400.1700 (retention time 6.905‒6.961). One of these peaks can be assigned to the product 2a, while the other peak showed that the deacylated product 3a is formed during the transformation with subsequent oxidation by sulfur in the oxidation/reduction step to form 2,5-dihydrothiophene 1-oxide 2a′ (Figure 1, a and b and Scheme 6).

![[1860-5397-22-13-1]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-22-13-1.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 1: HRMS analysis of the crude product.

Figure 1: HRMS analysis of the crude product.

The analysis also suggests the formation of product 2a before water and acid were added. This also indicates that the reaction proceeded through an oxidation/reduction step.

UV absorption measurements of the same reaction mixture (a) and pure product 2a (b) dissolved in methanol are presented in Figure 2.

![[1860-5397-22-13-2]](/bjoc/content/figures/1860-5397-22-13-2.png?scale=2.0&max-width=1024&background=FFFFFF)

Figure 2: UV–vis spectra of the crude mixture (5.6 mg of the crude mixture was dissolved in 15 mL of methanol and the aliquot (100 µL) was diluted in 900 µL of methanol) (a) and purified product 2a (с = 5 × 10−5 M) (b) in methanol at 20 °C.

Figure 2: UV–vis spectra of the crude mixture (5.6 mg of the crude mixture was dissolved in 15 mL of methanol...

The formation of product 2a before water and acid were added also follows from the comparison of UV–vis spectra of crude mixture (a) and product 2a (b). According to the previously reported data [51], the absorption maximum in spectrum (a) at 220 nm is caused by the presence of elemental sulfur S6. Probably, the reaction is accompanied by the desulfurization of the oxidized intermediate, which causes the yellow color of the reaction solutions.

The proposed mechanism for the developed transformations is depicted in Scheme 6. The reaction of dihydrothiophene 1a with sodium ethoxide led to the intermediate A. Elimination of ethyl/methyl acetate from intermediate A afforded anion B. The latter reacted in ethanolic solution with molecular oxygen [52] with the formation of peroxide anion C. The protonation of anion C with proton sources (residual water or/and solvent or 3a can serve as a proton source) formed hydroperoxide D. On the other hand, competitive reversible proton movement [53] from ethanol to anion B formed deacetylated product 3a. The subsequent reduction of hydroperoxide D by the deacetylated product 3a results in the formation of hydroxy-substituted dihydrothiophene 2a and oxidized product 2a′. The latter, probably, undergoes desulfurization into compound 3a′ (for example, base-promoted transformation of 2,5-dihydrothiophenes-1,1-dioxides to 1,3-dienes was reported by S. Zard [54]).

It can be assumed that the higher acidity of methanol in comparison with ethanol makes the proton transfer to anion B quasi-irreversible. This could be the cause for the selective formation of deacetylated dihydrothiophene 3a in methanolic solution.

The observed deacetylation for product 2m in ethanol on Scheme 2 can be caused by a decrease of the stability of the formed anion due to the stronger donor character of the pyrrolidine moiety due to its planar structure. The formation of the deacetylated products 2n,o (Scheme 2) may be attributed to increased steric hindrance, which makes proton transfer to B in Scheme 6 more difficult. The dimethyl-1-yl moiety likely exhibits a lower donor character compared to pyrrolidine, but higher than that of morpholine and piperidine. As a result, a mixture of products 2l and 2l′ is formed.

Starting dihydrothiophenes 1 form more stable anions B in comparison with regioisomers 4 due to the delocalization of the negative charge over the double bond, sulfur and amide group. The difference in the stability of these types of anions results in their distinct reactivity.

Conclusion

We have reported the solvent dependent transformation of dihydrothiophenes 1 under mild conditions. It was found that, in ethanolic solution in the presence of sodium ethoxide and molecular oxygen at ambient pressure, dihydrothiophenes 1a,b,d–l were oxidized into hydroxyderivatives 2a,b,d–l. In methanolic solution, in the presence of sodium methoxide and molecular oxygen, the same dihydrothiophenes 1a,b,d–l transformed into deacetylated products 3. Isomeric dihydrothiophenes 4a–f formed only deacetylated products 5a–f when the reaction was performed in an oxygen saturated ethanolic solution in the presence of sodium ethoxide.

Experimental

X-ray structure determination of 5g

5g: Crystal data for C17H18N2O2S (M = 314.40 g/mol): monoclinic, space group P−1, a = 9.3076 (5) Å, b = 9.3243(5) Å, c = 10.1072 (4) Å, β = 102.480(4)°, V = 776.19(7) Å3, Z = 2, μ(Mo Kα) = 0.217 mm−1, Dcalc = 1.345 g/cm3, 4252 reflections measured (7.378° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 61°), 4252 unique (Rint = 0.0407, Rsigma = 0.0545) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 = 0.0596, wR2 = 0.1470 (I >= 2σ(I)) and R1 = 0.0837, wR2 = 0.1768 (all data). Largest diff. peak/hole 0.29/−0.55 e−Å−3.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Full experimental details and characterization data of all new compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 1.3 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 2: Copies of NMR spectra of all new compounds. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 7.3 MB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 3: CIF-file for compound 5g. | ||

| Format: CIF | Size: 214.3 KB | Download |

| Supporting Information File 4: CheckCIF-file for compound 5g. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 247.2 KB | Download |

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is available in the published article and/or the supporting information of this article.

References

-

Bäckvall, J.-E., Ed. Modern Oxidation Methods; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. doi:10.1002/3527603689

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hentges, S. G.; Sharpless, K. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 4263–4265. doi:10.1021/ja00532a050

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Qin, T.; Li, J.-P.; Xie, M.-S.; Qu, G.-R.; Guo, H.-M. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 15512–15523. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02442

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sherstyuk, V. A.; Ottenbacher, R. V.; Talsi, E. P.; Bryliakov, K. P. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 498–507. doi:10.1021/acscatal.3c04832

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Filippov, I. P.; Novikov, M. S.; Rostovskii, N. V. Org. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 5811–5817. doi:10.1039/d5qo00717h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sharpless, K. B.; Akashi, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 5927–5928. doi:10.1021/ja00853a055

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bolm, C.; Fey, T. Chem. Commun. 1999, 1795–1796. doi:10.1039/a905683a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lin, M.; Hogan, T. E.; Sen, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4574–4580. doi:10.1021/ja953670r

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Meng, B.; Liu, L.; Shen, X.; Fan, W.; Li, S. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 11278–11283. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c00770

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Astakhov, G. S.; Bilyachenko, A. N.; Levitsky, M. M.; Shul’pina, L. S.; Korlyukov, A. A.; Zubavichus, Y. V.; Khrustalev, V. N.; Vologzhanina, A. V.; Shubina, E. S.; Dorovatovskii, P. V.; Shul’pin, G. B. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 4536–4545. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03680

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fatima, S.; Zahoor, A. F.; Khan, S. G.; Naqvi, S. A. R.; Hussain, S. M.; Nazeer, U.; Mansha, A.; Ahmad, H.; Chaudhry, A. R.; Irfan, A. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 23423–23458. doi:10.1039/d4ra03914a

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yaremenko, I. A.; Vil’, V. A.; Demchuk, D. V.; Terent’ev, A. O. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1647–1748. doi:10.3762/bjoc.12.162

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Kajigaeshi, S.; Nakagawa, T.; Nagasaki, N.; Fujisaki, S. Synthesis 1985, 674–675. doi:10.1055/s-1985-31305

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bjørsvik, H.-R.; Liguori, L.; Vedia Merinero, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 7493–7500. doi:10.1021/jo025916y

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Moriarty, R. M.; Prakash, I.; Penmasta, R. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1987, 202–203. doi:10.1039/c39870000202

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lee, J. C.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, Y. C. Synlett 2001, 1563–1564. doi:10.1055/s-2001-17474

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dakin, H. Am. Chem. J. 1909, 42, 477–478.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Baeyer, A.; Villiger, V. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1899, 32, 3625–3633. doi:10.1002/cber.189903203151

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pillai, U. R.; Sahle-Demessie, E. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2003, 191, 93–100. doi:10.1016/s1381-1169(02)00347-3

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bernini, R.; Coratti, A.; Provenzano, G.; Fabrizi, G.; Tofani, D. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 1821–1825. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.12.025

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Peris, G.; Miller, S. J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3049–3052. doi:10.1021/ol8010248

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yu, L.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Xu, Q. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 1804–1809. doi:10.1039/c5cy01395j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Nabae, Y.; Rokubuichi, H.; Mikuni, M.; Kuang, Y.; Hayakawa, T.; Kakimoto, M.-a. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 230–236. doi:10.1021/cs3007928

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.-K.; Ding, M. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 1704–1714. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c06769

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Roy, A.; Reddy, K. R.; Mohanta, P. K.; Ila, H.; Junjappat, H. Synth. Commun. 1999, 29, 3781–3791. doi:10.1080/00397919908086017

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] -

Hocking, M. B. Can. J. Chem. 1973, 51, 2384–2392. doi:10.1139/v73-357

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] [3] [4] -

Giraudo, A.; Armano, E.; Morano, C.; Pallavicini, M.; Bolchi, C. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 15461–15465. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c01513

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bora, P.; Bora, B.; Bora, U. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 17077–17084. doi:10.1039/d1nj03300j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Charushin, V. N.; Verbitskiy, E. V.; Chupakhin, O. N.; Vorobyeva, D. V.; Gribanov, P. S.; Osipov, S. N.; Ivanov, A. V.; Martynovskaya, S. V.; Sagitova, E. F.; Dyachenko, V. D.; Dyachenko, I. V.; Krivokolylsko, S. G.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Aksenov, A. V.; Aksenov, D. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Larin, A. A.; Fershtat, L. L.; Muzalevskiy, V. M.; Nenajdenko, V. G.; Gulevskaya, A. V.; Pozharskii, A. F.; Filatova, E. A.; Belyaeva, K. V.; Trofimov, B. A.; Balova, I. A.; Danilkina, N. A.; Govdi, A. I.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E.; Novikov, M. S.; Rostovskii, N. V.; Khlebnikov, A. F.; Klimochkin, Y. N.; Leonova, M. V.; Tkachenko, I. M.; Mamedov, V. A. O.; Mamedova, V. L.; Zhukova, N. A.; Semenov, V. E.; Sinyashin, O. G.; Borshchev, O. V.; Luponosov, Y. N.; Ponomarenko, S. A.; Fisyuk, A. S.; Kostyuchenko, A. S.; Ilkin, V. G.; Beryozkina, T. V.; Bakulev, V. A.; Gazizov, A. S.; Zagidullin, A. A.; Karasik, A. A.; Kukushkin, M. E.; Beloglazkina, E. K.; Golantsov, N. E.; Festa, A. A.; Voskresenskii, L. G.; Moshkin, V. S.; Buev, E. M.; Sosnovskikh, V. Y.; Mironova, I. A.; Postnikov, P. S.; Zhdankin, V. V.; Yusubov, M. S. O.; Yaremenko, I. A.; Vil', V. A.; Krylov, I. B.; Terent'ev, A. O.; Gorbunova, Y. G.; Martynov, A. G.; Tsivadze, A. Y.; Stuzhin, P. A.; Ivanova, S. S.; Koifman, O. I.; Burov, O. N.; Kletskii, M. E.; Kurbatov, S. V.; Yarovaya, O. I.; Volcho, K. P.; Salakhutdinov, N. F.; Panova, M. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Sitdikova, A. R.; Shchegravina, E. S.; Fedorov, A. Y. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5125. doi:10.59761/rcr5125

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yan, D.-M.; Zhao, Q.-Q.; Rao, L.; Chen, J.-R.; Xiao, W.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 16895–16901. doi:10.1002/chem.201804229

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hong, J. E.; Jeon, H.; Kwak, J.-H.; Lee, S.; Park, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 8152–8159. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5c00498

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Elliott, Q.; dos Passos Gomes, G.; Evoniuk, C. J.; Alabugin, I. V. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6539–6555. doi:10.1039/c9sc06511c

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ivanov, K. L.; Villemson, E. V.; Budynina, E. M.; Ivanova, O. A.; Trushkov, I. V.; Melnikov, M. Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 4975–4987. doi:10.1002/chem.201405551

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Tan, Z.; Chen, T.; Zhu, J.; Luo, W.; Yu, D.; Guo, W. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 2656–2664. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c02683

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, F.; Yan, X. Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 6915–6920. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.4c02576

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yaragorla, S.; Latha, D. S.; Rajesh, P. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 5486–5492. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101022

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Owen, T. C.; Harris, J. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 6136–6137. doi:10.1021/ja00172a044

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xu, Y.; Qi, X.; Zheng, P.; Berti, C. C.; Liu, P.; Dong, G. Nature 2019, 567, 373–378. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-0926-8

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gollnick, K.; Knutzen-Mies, K. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4027–4031. doi:10.1021/jo00012a041

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Birch, S. F.; McAllan, D. T. J. Chem. Soc. 1951, 2556–2563. doi:10.1039/jr9510002556

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

O’Neil, I. A.; Hamilton, K. M.; Miller, J. A.; Young, R. J. Synlett 1995, 151–152. doi:10.1055/s-1995-4895

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Capella, L.; Montevecchi, P. C.; Navacchia, M. L. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 6783–6789. doi:10.1021/jo960279v

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Shukla, G.; Raghuvanshi, K.; Singh, M. S. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 13935–13944. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.2c01617

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chen, Y.-Z.; Wang, D.-H.; Chen, B.; Zhong, J.-J.; Tung, C.-H.; Wu, L.-Z. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 6773–6777. doi:10.1021/jo3006123

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rahim, M. A.; Fujiwara, T.; Takeda, T. Synlett 1999, 1029–1032. doi:10.1055/s-1999-2777

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Martyres, D. H.; Baldwin, J. E.; Adlington, R. M.; Lee, V.; Probert, M. R.; Watkin, D. J. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 4999–5007. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)00430-6

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Sun, X.-H.; Li, S.-J.; Liu, Y.-F.; Chen, B.; Jia, Y.-Q.; Tao, Y. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 27, 82–86.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Flynn, B. L.; Flynn, G. P.; Hamel, E.; Jung, M. K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2341–2343. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00436-x

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Darwish, E. S. Molecules 2008, 13, 1066–1078. doi:10.3390/molecules13051066

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Ilkin, V. G.; Filimonov, V. O.; Utepova, I. A.; Beryozkina, T. V.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Tumashov, A. A.; Dehaen, W.; Bakulev, V. A. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 3537–3545. doi:10.1039/d3qo02025h

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Steudel, R., Ed. Elemental Sulfur und Sulfur-Rich Compounds II; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. doi:10.1007/b11909

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Prendergast, F. G. Nature 2000, 405, 291–292. doi:10.1038/35012734

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yamabe, S.; Yamazaki, S. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 3031–3041. doi:10.1021/jo0626562

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Lusinchi, M.; Stanbury, T. V.; Zard, S. Z. Chem. Commun. 2002, 1532–1533. doi:10.1039/b203975c

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 51. | Steudel, R., Ed. Elemental Sulfur und Sulfur-Rich Compounds II; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. doi:10.1007/b11909 |

| 1. | Bäckvall, J.-E., Ed. Modern Oxidation Methods; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. doi:10.1002/3527603689 |

| 11. | Fatima, S.; Zahoor, A. F.; Khan, S. G.; Naqvi, S. A. R.; Hussain, S. M.; Nazeer, U.; Mansha, A.; Ahmad, H.; Chaudhry, A. R.; Irfan, A. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 23423–23458. doi:10.1039/d4ra03914a |

| 27. | Giraudo, A.; Armano, E.; Morano, C.; Pallavicini, M.; Bolchi, C. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 15461–15465. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c01513 |

| 8. | Lin, M.; Hogan, T. E.; Sen, A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4574–4580. doi:10.1021/ja953670r |

| 9. | Meng, B.; Liu, L.; Shen, X.; Fan, W.; Li, S. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 11278–11283. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c00770 |

| 10. | Astakhov, G. S.; Bilyachenko, A. N.; Levitsky, M. M.; Shul’pina, L. S.; Korlyukov, A. A.; Zubavichus, Y. V.; Khrustalev, V. N.; Vologzhanina, A. V.; Shubina, E. S.; Dorovatovskii, P. V.; Shul’pin, G. B. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 4536–4545. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03680 |

| 20. | Bernini, R.; Coratti, A.; Provenzano, G.; Fabrizi, G.; Tofani, D. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 1821–1825. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.12.025 |

| 25. | Roy, A.; Reddy, K. R.; Mohanta, P. K.; Ila, H.; Junjappat, H. Synth. Commun. 1999, 29, 3781–3791. doi:10.1080/00397919908086017 |

| 26. | Hocking, M. B. Can. J. Chem. 1973, 51, 2384–2392. doi:10.1139/v73-357 |

| 6. | Sharpless, K. B.; Akashi, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 5927–5928. doi:10.1021/ja00853a055 |

| 7. | Bolm, C.; Fey, T. Chem. Commun. 1999, 1795–1796. doi:10.1039/a905683a |

| 23. | Nabae, Y.; Rokubuichi, H.; Mikuni, M.; Kuang, Y.; Hayakawa, T.; Kakimoto, M.-a. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 230–236. doi:10.1021/cs3007928 |

| 24. | Wu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.-K.; Ding, M. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 1704–1714. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c06769 |

| 2. | Hentges, S. G.; Sharpless, K. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 4263–4265. doi:10.1021/ja00532a050 |

| 3. | Qin, T.; Li, J.-P.; Xie, M.-S.; Qu, G.-R.; Guo, H.-M. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 15512–15523. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b02442 |

| 4. | Sherstyuk, V. A.; Ottenbacher, R. V.; Talsi, E. P.; Bryliakov, K. P. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 498–507. doi:10.1021/acscatal.3c04832 |

| 5. | Filippov, I. P.; Novikov, M. S.; Rostovskii, N. V. Org. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 5811–5817. doi:10.1039/d5qo00717h |

| 25. | Roy, A.; Reddy, K. R.; Mohanta, P. K.; Ila, H.; Junjappat, H. Synth. Commun. 1999, 29, 3781–3791. doi:10.1080/00397919908086017 |

| 26. | Hocking, M. B. Can. J. Chem. 1973, 51, 2384–2392. doi:10.1139/v73-357 |

| 15. | Moriarty, R. M.; Prakash, I.; Penmasta, R. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1987, 202–203. doi:10.1039/c39870000202 |

| 16. | Lee, J. C.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, Y. C. Synlett 2001, 1563–1564. doi:10.1055/s-2001-17474 |

| 18. | Baeyer, A.; Villiger, V. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1899, 32, 3625–3633. doi:10.1002/cber.189903203151 |

| 14. | Bjørsvik, H.-R.; Liguori, L.; Vedia Merinero, J. A. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 7493–7500. doi:10.1021/jo025916y |

| 19. | Pillai, U. R.; Sahle-Demessie, E. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2003, 191, 93–100. doi:10.1016/s1381-1169(02)00347-3 |

| 20. | Bernini, R.; Coratti, A.; Provenzano, G.; Fabrizi, G.; Tofani, D. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 1821–1825. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.12.025 |

| 21. | Peris, G.; Miller, S. J. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3049–3052. doi:10.1021/ol8010248 |

| 22. | Yu, L.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Xu, Q. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 1804–1809. doi:10.1039/c5cy01395j |

| 13. | Kajigaeshi, S.; Nakagawa, T.; Nagasaki, N.; Fujisaki, S. Synthesis 1985, 674–675. doi:10.1055/s-1985-31305 |

| 53. | Yamabe, S.; Yamazaki, S. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 3031–3041. doi:10.1021/jo0626562 |

| 12. | Yaremenko, I. A.; Vil’, V. A.; Demchuk, D. V.; Terent’ev, A. O. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1647–1748. doi:10.3762/bjoc.12.162 |

| 54. | Lusinchi, M.; Stanbury, T. V.; Zard, S. Z. Chem. Commun. 2002, 1532–1533. doi:10.1039/b203975c |

| 20. | Bernini, R.; Coratti, A.; Provenzano, G.; Fabrizi, G.; Tofani, D. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 1821–1825. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2004.12.025 |

| 25. | Roy, A.; Reddy, K. R.; Mohanta, P. K.; Ila, H.; Junjappat, H. Synth. Commun. 1999, 29, 3781–3791. doi:10.1080/00397919908086017 |

| 47. | Sun, X.-H.; Li, S.-J.; Liu, Y.-F.; Chen, B.; Jia, Y.-Q.; Tao, Y. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 27, 82–86. |

| 48. | Flynn, B. L.; Flynn, G. P.; Hamel, E.; Jung, M. K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2341–2343. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00436-x |

| 49. | Darwish, E. S. Molecules 2008, 13, 1066–1078. doi:10.3390/molecules13051066 |

| 50. | Ilkin, V. G.; Filimonov, V. O.; Utepova, I. A.; Beryozkina, T. V.; Slepukhin, P. A.; Tumashov, A. A.; Dehaen, W.; Bakulev, V. A. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 3537–3545. doi:10.1039/d3qo02025h |

| 39. | Gollnick, K.; Knutzen-Mies, K. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4027–4031. doi:10.1021/jo00012a041 |

| 40. | Birch, S. F.; McAllan, D. T. J. Chem. Soc. 1951, 2556–2563. doi:10.1039/jr9510002556 |

| 39. | Gollnick, K.; Knutzen-Mies, K. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4027–4031. doi:10.1021/jo00012a041 |

| 40. | Birch, S. F.; McAllan, D. T. J. Chem. Soc. 1951, 2556–2563. doi:10.1039/jr9510002556 |

| 41. | O’Neil, I. A.; Hamilton, K. M.; Miller, J. A.; Young, R. J. Synlett 1995, 151–152. doi:10.1055/s-1995-4895 |

| 42. | Capella, L.; Montevecchi, P. C.; Navacchia, M. L. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 6783–6789. doi:10.1021/jo960279v |

| 43. | Shukla, G.; Raghuvanshi, K.; Singh, M. S. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 13935–13944. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.2c01617 |

| 44. | Chen, Y.-Z.; Wang, D.-H.; Chen, B.; Zhong, J.-J.; Tung, C.-H.; Wu, L.-Z. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 6773–6777. doi:10.1021/jo3006123 |

| 45. | Rahim, M. A.; Fujiwara, T.; Takeda, T. Synlett 1999, 1029–1032. doi:10.1055/s-1999-2777 |

| 46. | Martyres, D. H.; Baldwin, J. E.; Adlington, R. M.; Lee, V.; Probert, M. R.; Watkin, D. J. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 4999–5007. doi:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)00430-6 |

| 30. | Yan, D.-M.; Zhao, Q.-Q.; Rao, L.; Chen, J.-R.; Xiao, W.-J. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 16895–16901. doi:10.1002/chem.201804229 |

| 31. | Hong, J. E.; Jeon, H.; Kwak, J.-H.; Lee, S.; Park, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 8152–8159. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5c00498 |

| 32. | Elliott, Q.; dos Passos Gomes, G.; Evoniuk, C. J.; Alabugin, I. V. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6539–6555. doi:10.1039/c9sc06511c |

| 33. | Ivanov, K. L.; Villemson, E. V.; Budynina, E. M.; Ivanova, O. A.; Trushkov, I. V.; Melnikov, M. Y. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 4975–4987. doi:10.1002/chem.201405551 |

| 34. | Tan, Z.; Chen, T.; Zhu, J.; Luo, W.; Yu, D.; Guo, W. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 2656–2664. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.3c02683 |

| 35. | Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, F.; Yan, X. Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 6915–6920. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.4c02576 |

| 36. | Yaragorla, S.; Latha, D. S.; Rajesh, P. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 5486–5492. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101022 |

| 37. | Owen, T. C.; Harris, J. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 6136–6137. doi:10.1021/ja00172a044 |

| 38. | Xu, Y.; Qi, X.; Zheng, P.; Berti, C. C.; Liu, P.; Dong, G. Nature 2019, 567, 373–378. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-0926-8 |

| 28. | Bora, P.; Bora, B.; Bora, U. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 17077–17084. doi:10.1039/d1nj03300j |

| 29. | Charushin, V. N.; Verbitskiy, E. V.; Chupakhin, O. N.; Vorobyeva, D. V.; Gribanov, P. S.; Osipov, S. N.; Ivanov, A. V.; Martynovskaya, S. V.; Sagitova, E. F.; Dyachenko, V. D.; Dyachenko, I. V.; Krivokolylsko, S. G.; Dotsenko, V. V.; Aksenov, A. V.; Aksenov, D. A.; Aksenov, N. A.; Larin, A. A.; Fershtat, L. L.; Muzalevskiy, V. M.; Nenajdenko, V. G.; Gulevskaya, A. V.; Pozharskii, A. F.; Filatova, E. A.; Belyaeva, K. V.; Trofimov, B. A.; Balova, I. A.; Danilkina, N. A.; Govdi, A. I.; Tikhomirov, A. S.; Shchekotikhin, A. E.; Novikov, M. S.; Rostovskii, N. V.; Khlebnikov, A. F.; Klimochkin, Y. N.; Leonova, M. V.; Tkachenko, I. M.; Mamedov, V. A. O.; Mamedova, V. L.; Zhukova, N. A.; Semenov, V. E.; Sinyashin, O. G.; Borshchev, O. V.; Luponosov, Y. N.; Ponomarenko, S. A.; Fisyuk, A. S.; Kostyuchenko, A. S.; Ilkin, V. G.; Beryozkina, T. V.; Bakulev, V. A.; Gazizov, A. S.; Zagidullin, A. A.; Karasik, A. A.; Kukushkin, M. E.; Beloglazkina, E. K.; Golantsov, N. E.; Festa, A. A.; Voskresenskii, L. G.; Moshkin, V. S.; Buev, E. M.; Sosnovskikh, V. Y.; Mironova, I. A.; Postnikov, P. S.; Zhdankin, V. V.; Yusubov, M. S. O.; Yaremenko, I. A.; Vil', V. A.; Krylov, I. B.; Terent'ev, A. O.; Gorbunova, Y. G.; Martynov, A. G.; Tsivadze, A. Y.; Stuzhin, P. A.; Ivanova, S. S.; Koifman, O. I.; Burov, O. N.; Kletskii, M. E.; Kurbatov, S. V.; Yarovaya, O. I.; Volcho, K. P.; Salakhutdinov, N. F.; Panova, M. A.; Burgart, Y. V.; Saloutin, V. I.; Sitdikova, A. R.; Shchegravina, E. S.; Fedorov, A. Y. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5125. doi:10.59761/rcr5125 |

© 2026 Ilkin et al.; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Beilstein-Institut Open Access License Agreement (https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/terms), which is identical to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). The reuse of material under this license requires that the author(s), source and license are credited. Third-party material in this article could be subject to other licenses (typically indicated in the credit line), and in this case, users are required to obtain permission from the license holder to reuse the material.