Abstract

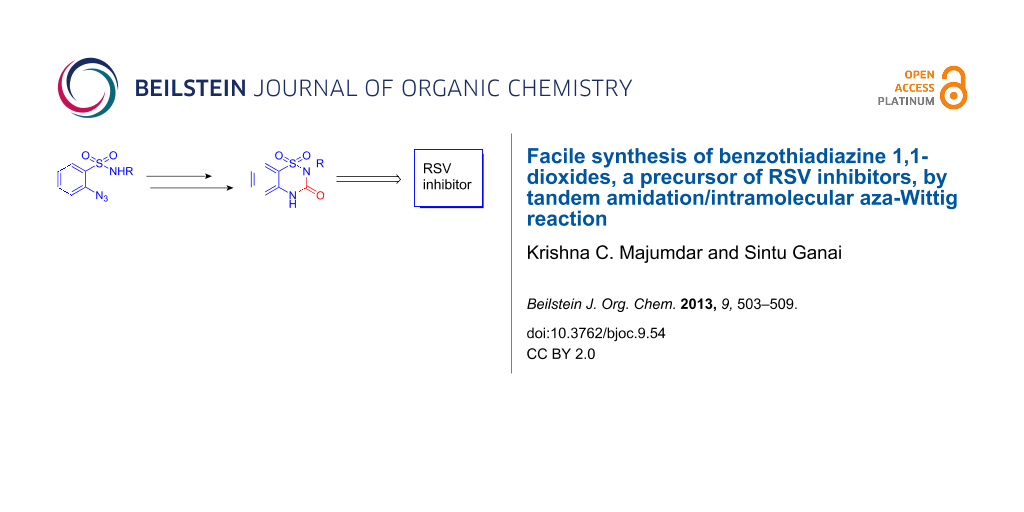

Reaction of o-azidobenzenesulfonamides with ethyl carbonochloridate afforded the corresponding amide derivatives, which gave 3-ethoxy-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxides through an intramolecular aza-Wittig reaction. The reaction was found to be general through the synthesis of a number of benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxides. Acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of 3-ethoxy-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxides furnished the 2-substituted benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxides in good yields and high purity, which is the core moiety of RSV inhibitors.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Sultams have gained popularity in the scientific community especially among synthetic and medicinal chemists, because this basic moiety is present in many natural products and biologically active substances [1-8]. Especially, benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxide and its derivatives possess potential activity, including hypoglycemic [9], anticancer and anti-HIV activity [10-13], and also serve as selective antagonists of CXR2 [14]. 2-Substituted-2H-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine-3(4H)one 1,1-dioxides showed varying degrees of sedative and hypotensive activities [15]. A number of benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide derivatives have recently been reported that display potent activity [16-22], including hypoglycemic (1), anti-HIV (2), HIV-1 specific non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (3), sedative (4), and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) inhibitory activity (5; Figure 1).

Figure 1: Biologically active 1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide derivatives.

Figure 1: Biologically active 1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide derivatives.

A literature search revealed that the 1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxides are generally synthesized either by condensation of o-aminobenzenesulfonamides with urea at elevated temperature [23] or by the reaction of o-aminobenzenesulfonamide with isocyanates in DMF under reflux [24]. Although various approaches to the preparation of 1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide derivatives have been reported [25-32], the development of a simpler method for the synthesis of the 1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide moiety is still desirable because of their biological significance.

The aza-Wittig reaction is employed for the construction of C=N, N=N and S=N double bonds in various heterocycles and heterocycle-containing natural products [33-43]. Recently, we have synthesized asymmetrically substituted piperazine-2,5-dione derivatives using the intramolecular aza-Wittig reaction [44]. In continuation of our earlier work [45-51], we have undertaken a study to synthesize 1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide derivatives using an intramolecular aza-Wittig reaction as the key step. Herein we report our results.

Retrosynthetic analysis of the RSV inhibitors 5 and 6 relied on benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxide 7, which can easily be obtained by simple hydrolysis of the benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide derivative 8. Construction of this six-membered sultam 8 was thought to be achieved by intramolecular aza-Wittig reaction of the o-azido derivative 9. The following retrosynthetic analysis led us to the starting material o-azidobenzenesulfonic acid (11) for the synthesis of the intermediate 10 necessary for the synthesis of RSV inhibitors (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Retrosynthesis analysis of RSV inhibitors.

Scheme 1: Retrosynthesis analysis of RSV inhibitors.

Results and Discussion

Sulfonic acid 11 bearing an o-azido group [30] was converted into the corresponding sulfonyl chloride by treatment with oxalyl chloride followed by the reaction with appropriate amines to give the requisite 2-azido-N-substituted benzenesulfonamides 10a–i. The sulfonamide 10b was reacted with ethyl carbonochloridate to afford the corresponding amide derivative 9b required for our study. Initially, we turned our attention to the synthesis of a benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide derivative using substrate 9b by intramolecular aza-Wittig reaction. To test this premise, 9b was treated with triphenylphosphine in THF at room temperature, but no desired product was obtained, and only the intermediate iminophosphorane 12b was isolated, even under reflux (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2: Preparation of 3-ethoxy-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide. Reagent and conditions: (i) (COCl)2, DMF, CH2Cl2, reflux, 3 h; (ii) RNH2, NaOAc, MeOH + water, 60 °C; (iii) ClCO2C2H5, acetone, Et3N, rt, 5 h; (iv) PPh3, THF, reflux, 10 h; (v) PPh3, DCB, 135 °C, 8 h.

Scheme 2: Preparation of 3-ethoxy-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide. Reagent and conditions: (i) (COCl)2, DM...

We next conducted a series of reactions with the replacement of the solvent THF by other solvents, such as toluene, CH2Cl2, and CH3CN, but none of them afforded any cyclized product (Table 1, entries 2–4,). Then the reaction conditions were modified through the use of a higher-boiling-point solvent, i.e., o-dichlorobenzene (DCB). The reaction was successful at higher temperature, affording the desired cyclized product 13b (54%) along with the by-product triphenylphosphine oxide (Table 1, entry 5).

Table 1: Summary of the intramolecular aza-Wittig reactions.a

|

|

||||

| Entry | Solvent | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | Yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | THF | reflux | 6 | 0 |

| 2c | toluene | 120 °C | 8 | 0 |

| 3c | CH2Cl2 | reflux | 8 | 0 |

| 4c | CH3CN | reflux | 6 | 0 |

| 5 | DCB | 135 °C | 8 | 54 |

aAll the reactions were carried out with 1 equiv 9b and 1.5 equiv PPh3; bisolated yields of 13b; conly 12b was separated.

Subsequently, we turned our attention to develop a simpler one-step procedure by heating the sulfonamide 10b with ethyl carbonochloridate, Et3N and PPh3 in DCB at 135 °C for 6 h, which gave the cyclized product 13b in 78% yield (Table 2, entry 1). The base Et3N was then replaced by Cs2CO3 or K2CO3, but no better result was obtained (Table 2, entries 2 and 3). Only DIPEA gave 69% yield of the product (Table 2, entry 4). However, surprisingly the use of xylene as the solvent improved the yield of the cyclized product (Table 2, entry 5). The replacement of NEt3 by DIPEA as the base also gave a similar yield of the product (Table 2, entry 6). The decomposition of the iminophosphorane intermediate into the corresponding amine derivative 14b was found to occur at higher temperature (150 °C) producing a low yield of the cyclized product (Table 2, entry 7). The reaction did not occur at all in the absence of a base (Table 2, entry 8). The observations are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Summary of the intramolecular aza-Wittig reactions in a one-pot fashion.a

|

|

|||||

| Entry | Solvent | Base | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | Yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DCB | Et3N | 135 °C | 6 | 78 |

| 2 | DCB | K2CO3 | 135 °C | 8 | <30 |

| 3 | DCB | Cs2CO3 | 135 °C | 8 | 46 |

| 4 | DCB | DIPEA | 135 °C | 6 | 69 |

| 5 | xylene | Et3N | 135 °C | 6 | 94 |

| 6 | xylene | DIPEA | 135 °C | 6 | 92 |

| 7c | xylene | Et3N | 150 °C | 6 | 5 |

| 8 | xylene | – | 135 °C | 10 | 0 |

aAll the reactions were carried out with 1 equiv 10b, 1.5 equiv ClCO2Et, 2 equiv base, and 1.5 equiv PPh3; bisolated yields of 13b; ca smaller amount of 13b was isolated than the major product 14b.

It is notable that xylene appears to be a suitable solvent for this reaction. We then carried out the reactions with a variety of substrates 10a–i under the optimized conditions (ethyl carbonochloridate, PPh3, Et3N, xylene at 135 °C) in order to generalize the method, and the results are summarized in Table 3. The reactions of all the substrates having electron-deficient R-substituents at the 2-position proceeded smoothly, providing excellent yields, whereas the substrates having electron-donating R-substituents gave lower yields.

Table 3: Generalization of intramolecular aza-Wittig reaction.a

|

|

||||

| Entry | o-azidosulfonamide | Time (h) | Product | Yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10a, R = C6H5 | 8 | 13a, R = C6H5 | 90 |

| 2 | 10b, R = 4-Cl-C6H4 | 6 | 13b, R = 4-Cl-C6H4 | 94 |

| 3 | 10c, R = 4-COCH3-C6H4 | 6 | 13c, R = 4-COCH3-C6H4 | 92 |

| 4 | 10d, R = 4-CO2CH3-C6H4 | 6 | 13d, R = 4-CO2CH3-C6H4 | 95 |

| 5 | 10e, R = 4-CH3-C6H4 | 7 | 13e, R = 4-CH3-C6H4 | 80 |

| 6 | 10f, R = 4-OCH3-C6H4 | 7 | 13f, R = 4-OCH3-C6H4 | 83 |

| 7 | 10g, R = -CH2C6H5 | 7 | 13g, R = -CH2C6H5 | 87 |

| 8 | 10h, R = CH3 | 7 | 13h, R = CH3 | 79 |

| 9 |

10i, R = |

6 |

13i, R = |

89 |

aReaction conditions: Compound 10 (1 mmol), ClCO2C2H5 (1.5 mmol), Et3N (2 mmol) and PPh3 (1.5 mmol) were heated at 135 °C in xylene; bisolated yields of compound 13.

The proposed mechanism for the formation of the products 13 may involve amidation of SO2NH2 by the reaction of nucleophilic sulfonamide 10 with ethyl carbonochloridate in the presence of Et3N to form the intermediates 9, which may then undergo intramolecular aza-Wittig reaction via the formation of iminophosphorane intermediate I. We isolated iminophosphorane intermediate 12b from the reaction with 10b at room temperature. In the presence of heat the iminophosphorane intermediate I leads to the formation of the product 3-ethoxy-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide 13 (Scheme 3). However, in all other cases we did not carry out the reactions at room temperature for isolation of the intermediates.

Scheme 3: Rationalization of the formation of compound 13.

Scheme 3: Rationalization of the formation of compound 13.

We have also demonstrated the conversion of the products 13 to the 2-substituted benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxide 15 by hydrolysing 13 with ethanolic HCl. The benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxide derivatives 15c,e,h were obtained in excellent yields from the compounds 13c,e,h (Scheme 4). These 2-substituted benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxides may further be alkylated at the 4-position with suitable halides to yield the RSV inhibitors 5 and 6 by using the reported [13] procedure.

Scheme 4: Preparation of benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxide derivatives by acid-catalyzed hydrolysis; reagents and conditions: 50 mg of compound 13, 1 mL HCl, 4 mL ethanol, 80 °C, 4 h.

Scheme 4: Preparation of benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxide derivatives by acid-catalyzed hydrolysis; reagent...

Previously, Jung and Khazi [52] reported the synthesis of the benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide moiety from the reaction of o-aminobenzenesulfonamide with the costlier triphosgene, whereas in our case the synthesis of benzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide derivatives was achieved from o-azidobenzenesulfonamides and required cheaper ethyl carbonochloridate as the reagent.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a simple and efficient method for the synthesis of 3-ethoxybenzothiadiazine 1,1-dioxide and benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxide derivatives starting from an easy precursor, by the application of an intramolecular aza-Wittig reaction. The reaction procedure is very simple and gives good to excellent yields of the products. This benzothiadiazine-3-one 1,1-dioxide can further be alkylated at the 4-position, following a literature procedure, to give the bioactive RSV inhibitors.

Supporting Information

| Supporting Information File 1: Experimental part. | ||

| Format: PDF | Size: 228.6 KB | Download |

Acknowledgements

We thank CSIR (New Delhi) and DST (New Delhi) for financial assistance. S.G. is grateful to CSIR (New Delhi) for his research fellowships, and K.C.M. is thankful to UGC (New Delhi) for a UGC Emeritus fellowship. We also thank DST (New Delhi) for providing the Bruker NMR (400 MHz), the Perkin-Elmer CHN Analyser, and the FTIR and UV–vis spectrometers.

References

-

Majumdar, K. C.; Mondal, S. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7749–7773. doi:10.1021/cr1003776

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Bernotas, R. C.; Dooley, R. J. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 2273–2276. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.01.092

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhou, A.; Rayabarapu, D.; Hanson, P. R. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 531–534. doi:10.1021/ol802467f

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Jiménez-Hopkins, M.; Hanson, P. R. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2223–2226. doi:10.1021/ol800649n

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Supuran, C. T.; Casini, A.; Scozzafava, A. Med. Res. Rev. 2003, 23, 535–558. doi:10.1002/med.10047

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hanessian, S.; Sailes, H.; Therrien, E. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7047–7056. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(03)00919-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Dauban, P.; Dodd, R. H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 1037–1040. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)02214-0

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Drews, J. Science 2000, 287, 1960–1964. doi:10.1126/science.287.5460.1960

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Wales, J. K.; Krees, S. V.; Grant, A. M.; Vikroa, J. K.; Wolff, F. W. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1968, 164, 421–432.

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scozzofava, A.; Owa, T.; Mastrolorenzo, A.; Supuran, C. T. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 925–953. doi:10.2174/0929867033457647

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Casini, A.; Scozzafava, A.; Mastrolorenco, A.; Supuran, C. T. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2002, 2, 55–75. doi:10.2174/1568009023334060

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Scozzafava, A.; Casini, A.; Supuran, C. T. Curr. Med. Chem. 2002, 9, 1167–1185. doi:10.2174/0929867023370077

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Arranz, E. M.; Díaz, J. A.; Ingate, S. T.; Witvrouw, M.; Pannecouque, C.; Balzarini, J.; De Clercq, E.; Vega, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 2811–2822. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(99)00221-7

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Wang, Y.; Busch-Petersen, J.; Wang, F.; Ma, L.; Fu, W.; Kerns, J. K.; Jin, J.; Palovich, M. R.; Shen, J.-K.; Burman, M.; Foley, J. J.; Schmidt, D. B.; Hunsberger, G. E.; Sarau, H. M.; Widdowson, K. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 3864–3867. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.05.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hayao, S.; Stryker, W.; Phillips, B.; Fujimori, H.; Vidrio, H. J. Med. Chem. 1968, 11, 1246–1248. doi:10.1021/jm00312a601

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khelili, S.; Kihal, N.; Yekhlef, M.; de Tullio, P.; Lebrun, P.; Pirotte, B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 54, 873–878. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.05.011

Return to citation in text: [1] -

de Tullio, P.; Servais, A.-C.; Fillet, M.; Gillotin, F.; Somers, F.; Chiap, P.; Lebrun, P.; Pirotte, B. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 8353–8361. doi:10.1021/jm200786z

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Francotte, P.; Goffin, E.; Fraikin, P.; Lestage, P.; van Heugen, J.-C.; Gillotin, F.; Danober, L.; Thomas, J.-Y.; Chiap, P.; Caignard, D.-H.; Pirotte, B.; de Tullio, P. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 1700–1711. doi:10.1021/jm901495t

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Pirotte, B.; de Tullio, P.; Nguyen, Q.-A.; Somers, F.; Fraikin, P.; Florence, X.; Wahl, P.; Hansen, J. B.; Lebrun, P. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 147–154. doi:10.1021/jm9010093

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Francotte, P.; de Tullio, P.; Goffin, E.; Dintilhac, G.; Graindorge, E.; Fraikin, P.; Lestage, P.; Danober, L.; Thomas, J.-Y.; Caignard, D.-H.; Pirotte, B. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 3153–3157. doi:10.1021/jm070120i

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Combrink, K. D.; Gulgeze, H. B.; Thuring, J. W.; Yu, K.-L.; Civiello, R. L.; Zhang, Y.; Pearce, B. C.; Yin, Z.; Langley, D. R.; Kadow, K. F.; Cianci, C. W.; Li, Z.; Clarke, J.; Genovesi, E. V.; Medina, I.; Lamb, L.; Yang, Z.; Zadjura, L.; Krystal, M.; Meanwell, N. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 4784–4790. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.065

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Boverie, S.; Antoine, M.-H.; Somers, F.; Becker, B.; Sebille, S.; Ouedraogo, R.; Counerotte, S.; Pirotte, B.; Lebrun, P.; de Tullio, P. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3492–3503. doi:10.1021/jm0311339

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Girard, Y.; Atkinson, J. G.; Rokach, J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1979, 1043–1047. doi:10.1039/P19790001043

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Chern, J.-W.; Ho, C.-P.; Wu, Y.-H.; Rong, J.-G.; Liu, K.-C.; Cheng, M.-C.; Wang, Y. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1990, 27, 1909–1915. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570270712

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cherepakha, A.; Kovtunenko, V. O.; Tolmachev, A.; Lukin, O. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 6233–6239. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.06.063

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hirota, S.; Sakai, T.; Kitamura, N.; Kubokawa, K.; Kutsumura, N.; Otani, T.; Saito, T. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 653–662. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.11.064

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Yang, D.; Liu, H.; Yang, H.; Fu, H.; Hu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 1999–2004. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900101

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Rolfe, A.; Hanson, P. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 6935–6937. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.09.090

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Hirota, S.; Kato, R.; Suzuki, M.; Soneta, Y.; Otani, T.; Saito, T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2075–2083. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200701131

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Blackburn, C.; Achab, A.; Elder, A.; Ghosh, S.; Guo, J.; Harriman, G.; Jones, M. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 10206–10209. doi:10.1021/jo051843h

Return to citation in text: [1] [2] -

Su, W.; Cai, H.; Yang, B. J. Chem. Res. 2004, 87–88. doi:10.3184/030823404323000936

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Makino, S.; Nakanishi, E.; Tsuji, T. J. Comb. Chem. 2003, 5, 73–78. doi:10.1021/cc020056k

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Xie, H.; Yuan, D.; Ding, M.-W. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 2954–2958. doi:10.1021/jo202588j

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Zhong, Y.; Wang, L.; Ding, M.-W. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3714–3723. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.056

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Palacios, F.; Alonso, C.; Aparicio, D.; Rubiales, G.; de los Santos, J. M. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 523–575. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.09.048

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cossío, F. P.; Alonso, C.; Lecea, B.; Ayerbe, M.; Rubiales, G.; Palacios, F. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 2839–2847. doi:10.1021/jo0525884

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Palacios, F.; Aparicio, D.; Rubiales, G.; Alonso, C.; de los Santos, J. M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2006, 10, 2371–2392. doi:10.2174/138527206778992716

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Eguchi, S. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2006, 6, 113–156. doi:10.1007/7081_022

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Cassidy, M. P.; Özdemir, A. D.; Padwa, A. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 1339–1342. doi:10.1021/ol0501323

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Snider, B. B.; Zhon, J. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 1087–1088. doi:10.1021/jo048131w

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Gil, C.; Bräse, S. Chem.–Eur. J. 2005, 11, 2680–2688. doi:10.1002/chem.200401112

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Alajarín, M.; Sánchez-Andrada, P.; Vidal, A.; Tovar, F. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 1340–1349. doi:10.1021/jo0482716

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Fresneda, P. M.; Molina, P. Synlett 2004, 1–17. doi:10.1055/s-2003-43338

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Ray, K.; Ganai, S. Synlett 2010, 2122–2124. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258519

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S.; Sinha, B. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 7806–7811. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.040

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S.; Nandi, R. K.; Ray, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 1553–1557. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.01.015

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S.; Nandi, R. K. New J. Chem. 2011, 35, 1355–1359. doi:10.1039/c1nj20121b

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S.; Chattopadhyay, B.; Ray, K. Synlett 2011, 2369–2373. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1260312

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S. Synlett 2011, 1881–1887. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1260975

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Ray, K.; Ganai, S.; Ghosh, T. Synthesis 2010, 858–862. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1218610

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Majumdar, K. C.; Ray, K.; Ganai, S. Synthesis 2010, 2101–2105. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1218763

Return to citation in text: [1] -

Khazi, I. A.; Jung, Y.-S. Lett. Org. Chem. 2007, 4, 423–428. doi:10.2174/157017807781467641

Return to citation in text: [1]

| 1. | Majumdar, K. C.; Mondal, S. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7749–7773. doi:10.1021/cr1003776 |

| 2. | Bernotas, R. C.; Dooley, R. J. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 2273–2276. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.01.092 |

| 3. | Zhou, A.; Rayabarapu, D.; Hanson, P. R. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 531–534. doi:10.1021/ol802467f |

| 4. | Jiménez-Hopkins, M.; Hanson, P. R. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2223–2226. doi:10.1021/ol800649n |

| 5. | Supuran, C. T.; Casini, A.; Scozzafava, A. Med. Res. Rev. 2003, 23, 535–558. doi:10.1002/med.10047 |

| 6. | Hanessian, S.; Sailes, H.; Therrien, E. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7047–7056. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(03)00919-0 |

| 7. | Dauban, P.; Dodd, R. H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 1037–1040. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)02214-0 |

| 8. | Drews, J. Science 2000, 287, 1960–1964. doi:10.1126/science.287.5460.1960 |

| 15. | Hayao, S.; Stryker, W.; Phillips, B.; Fujimori, H.; Vidrio, H. J. Med. Chem. 1968, 11, 1246–1248. doi:10.1021/jm00312a601 |

| 52. | Khazi, I. A.; Jung, Y.-S. Lett. Org. Chem. 2007, 4, 423–428. doi:10.2174/157017807781467641 |

| 14. | Wang, Y.; Busch-Petersen, J.; Wang, F.; Ma, L.; Fu, W.; Kerns, J. K.; Jin, J.; Palovich, M. R.; Shen, J.-K.; Burman, M.; Foley, J. J.; Schmidt, D. B.; Hunsberger, G. E.; Sarau, H. M.; Widdowson, K. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 3864–3867. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.05.011 |

| 10. | Scozzofava, A.; Owa, T.; Mastrolorenzo, A.; Supuran, C. T. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 925–953. doi:10.2174/0929867033457647 |

| 11. | Casini, A.; Scozzafava, A.; Mastrolorenco, A.; Supuran, C. T. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2002, 2, 55–75. doi:10.2174/1568009023334060 |

| 12. | Scozzafava, A.; Casini, A.; Supuran, C. T. Curr. Med. Chem. 2002, 9, 1167–1185. doi:10.2174/0929867023370077 |

| 13. | Arranz, E. M.; Díaz, J. A.; Ingate, S. T.; Witvrouw, M.; Pannecouque, C.; Balzarini, J.; De Clercq, E.; Vega, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 2811–2822. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(99)00221-7 |

| 30. | Blackburn, C.; Achab, A.; Elder, A.; Ghosh, S.; Guo, J.; Harriman, G.; Jones, M. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 10206–10209. doi:10.1021/jo051843h |

| 9. | Wales, J. K.; Krees, S. V.; Grant, A. M.; Vikroa, J. K.; Wolff, F. W. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1968, 164, 421–432. |

| 13. | Arranz, E. M.; Díaz, J. A.; Ingate, S. T.; Witvrouw, M.; Pannecouque, C.; Balzarini, J.; De Clercq, E.; Vega, S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 2811–2822. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(99)00221-7 |

| 25. | Cherepakha, A.; Kovtunenko, V. O.; Tolmachev, A.; Lukin, O. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 6233–6239. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.06.063 |

| 26. | Hirota, S.; Sakai, T.; Kitamura, N.; Kubokawa, K.; Kutsumura, N.; Otani, T.; Saito, T. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 653–662. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2009.11.064 |

| 27. | Yang, D.; Liu, H.; Yang, H.; Fu, H.; Hu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 1999–2004. doi:10.1002/adsc.200900101 |

| 28. | Rolfe, A.; Hanson, P. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 6935–6937. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.09.090 |

| 29. | Hirota, S.; Kato, R.; Suzuki, M.; Soneta, Y.; Otani, T.; Saito, T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2075–2083. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200701131 |

| 30. | Blackburn, C.; Achab, A.; Elder, A.; Ghosh, S.; Guo, J.; Harriman, G.; Jones, M. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 10206–10209. doi:10.1021/jo051843h |

| 31. | Su, W.; Cai, H.; Yang, B. J. Chem. Res. 2004, 87–88. doi:10.3184/030823404323000936 |

| 32. | Makino, S.; Nakanishi, E.; Tsuji, T. J. Comb. Chem. 2003, 5, 73–78. doi:10.1021/cc020056k |

| 44. | Majumdar, K. C.; Ray, K.; Ganai, S. Synlett 2010, 2122–2124. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1258519 |

| 24. | Chern, J.-W.; Ho, C.-P.; Wu, Y.-H.; Rong, J.-G.; Liu, K.-C.; Cheng, M.-C.; Wang, Y. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1990, 27, 1909–1915. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570270712 |

| 45. | Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S.; Sinha, B. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 7806–7811. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.040 |

| 46. | Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S.; Nandi, R. K.; Ray, K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 1553–1557. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.01.015 |

| 47. | Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S.; Nandi, R. K. New J. Chem. 2011, 35, 1355–1359. doi:10.1039/c1nj20121b |

| 48. | Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S.; Chattopadhyay, B.; Ray, K. Synlett 2011, 2369–2373. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1260312 |

| 49. | Majumdar, K. C.; Ganai, S. Synlett 2011, 1881–1887. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1260975 |

| 50. | Majumdar, K. C.; Ray, K.; Ganai, S.; Ghosh, T. Synthesis 2010, 858–862. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1218610 |

| 51. | Majumdar, K. C.; Ray, K.; Ganai, S. Synthesis 2010, 2101–2105. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1218763 |

| 23. | Girard, Y.; Atkinson, J. G.; Rokach, J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1979, 1043–1047. doi:10.1039/P19790001043 |

| 16. | Khelili, S.; Kihal, N.; Yekhlef, M.; de Tullio, P.; Lebrun, P.; Pirotte, B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 54, 873–878. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.05.011 |

| 17. | de Tullio, P.; Servais, A.-C.; Fillet, M.; Gillotin, F.; Somers, F.; Chiap, P.; Lebrun, P.; Pirotte, B. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 8353–8361. doi:10.1021/jm200786z |

| 18. | Francotte, P.; Goffin, E.; Fraikin, P.; Lestage, P.; van Heugen, J.-C.; Gillotin, F.; Danober, L.; Thomas, J.-Y.; Chiap, P.; Caignard, D.-H.; Pirotte, B.; de Tullio, P. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 1700–1711. doi:10.1021/jm901495t |

| 19. | Pirotte, B.; de Tullio, P.; Nguyen, Q.-A.; Somers, F.; Fraikin, P.; Florence, X.; Wahl, P.; Hansen, J. B.; Lebrun, P. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 147–154. doi:10.1021/jm9010093 |

| 20. | Francotte, P.; de Tullio, P.; Goffin, E.; Dintilhac, G.; Graindorge, E.; Fraikin, P.; Lestage, P.; Danober, L.; Thomas, J.-Y.; Caignard, D.-H.; Pirotte, B. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 3153–3157. doi:10.1021/jm070120i |

| 21. | Combrink, K. D.; Gulgeze, H. B.; Thuring, J. W.; Yu, K.-L.; Civiello, R. L.; Zhang, Y.; Pearce, B. C.; Yin, Z.; Langley, D. R.; Kadow, K. F.; Cianci, C. W.; Li, Z.; Clarke, J.; Genovesi, E. V.; Medina, I.; Lamb, L.; Yang, Z.; Zadjura, L.; Krystal, M.; Meanwell, N. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 4784–4790. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.065 |

| 22. | Boverie, S.; Antoine, M.-H.; Somers, F.; Becker, B.; Sebille, S.; Ouedraogo, R.; Counerotte, S.; Pirotte, B.; Lebrun, P.; de Tullio, P. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3492–3503. doi:10.1021/jm0311339 |

| 33. | Xie, H.; Yuan, D.; Ding, M.-W. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 2954–2958. doi:10.1021/jo202588j |

| 34. | Zhong, Y.; Wang, L.; Ding, M.-W. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3714–3723. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.056 |

| 35. | Palacios, F.; Alonso, C.; Aparicio, D.; Rubiales, G.; de los Santos, J. M. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 523–575. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.09.048 |

| 36. | Cossío, F. P.; Alonso, C.; Lecea, B.; Ayerbe, M.; Rubiales, G.; Palacios, F. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 2839–2847. doi:10.1021/jo0525884 |

| 37. | Palacios, F.; Aparicio, D.; Rubiales, G.; Alonso, C.; de los Santos, J. M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2006, 10, 2371–2392. doi:10.2174/138527206778992716 |

| 38. | Eguchi, S. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2006, 6, 113–156. doi:10.1007/7081_022 |

| 39. | Cassidy, M. P.; Özdemir, A. D.; Padwa, A. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 1339–1342. doi:10.1021/ol0501323 |

| 40. | Snider, B. B.; Zhon, J. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 1087–1088. doi:10.1021/jo048131w |

| 41. | Gil, C.; Bräse, S. Chem.–Eur. J. 2005, 11, 2680–2688. doi:10.1002/chem.200401112 |

| 42. | Alajarín, M.; Sánchez-Andrada, P.; Vidal, A.; Tovar, F. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 1340–1349. doi:10.1021/jo0482716 |

| 43. | Fresneda, P. M.; Molina, P. Synlett 2004, 1–17. doi:10.1055/s-2003-43338 |

© 2013 Majumdar and Ganai; licensee Beilstein-Institut.

This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The license is subject to the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry terms and conditions: (http://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc)